Syria Update

18 October to 24 October, 2018

Northwestern Syria Disarmament Zone

On October 18, U.N. Senior Advisor for Syria Jan Egeland, speaking at a press conference in Geneva, stated that “the Russian and Turkish sides have indicated that more time will be given to implementing the [disarmament zone] agreement.” Egeland did not state how long the implementation deadline was extended, though he added that “we have now had five weeks without any attack. I cannot remember such a period for the last three years in Idlib.” The original deadline to implement the terms of the disarmament zone agreement, as concluded by the Governments of Turkey and Russia in September 2018 in Sochi, was on October 15. Indeed, local sources indicate that the National Liberation Front has largely withdrawn its heavy weapons from the disarmament zone.

Despite withdrawing from several, though not all, of its military positions along frontlines in northwestern Syria, Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham remains publicly ambivalent if not opposed to the disarmament zone agreement. On October 13, Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham released a statement noting that: “we have postponed our final decision [regarding our stance on the disarmament agreement]…we will continue our negotiations and communications with all revolutionary groups in Idleb, and people inside and outside Syria, to reach a final decision…we emphasize that we will not stop fighting [the Government of Syria] until we reach our revolutionary goal, to overthrow the regime…we will never deliver our weapons to anyone, as our weapons are the guarantee of our rights.”

Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham’s ‘postponement of a decision’ and continued insistence on overthrowing the Government of Syria, while still abiding by the terms of the disarmament agreement, reflects both the incredibly challenging political position in which the group now finds itself as well as ongoing internal tensions. The Government of Turkey is using both political negotiations and military threats (in the form of the Turkish-backed National Liberation Front) to compel Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham to abide by the disarmament agreement; Turkey does hold some sway over Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham, considering that the group is in control of the main Turkish border crossing into Idleb at Bab Elhawa. However, it is important to note that Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham is not a monolithic organization, and is consistently divided by its ideological foundation and more local objectives and considerations. Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham’s leadership and combatants consist of both hardliners, committed ideologically to global jihadist (many of whom are foreigners), and those grounded in Syria-specific objectives (many of whom are locals with deep community ties). While these divisions can be plastered over in the short term, geopolitics and practical realities such as the disarmament agreement will exacerbate internal divisions and have the potential to fragment the group politically and militarily. Indeed, on October 16, a group of five hardline jihadist groups (several of which are largely comprised of Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham defectors, such as Hurrass Eldeen) announced that they had already formed their own separate military operations room known as ‘Wa Harad Al-Mumineen’, and stated that they are breaking their allegiance to all other armed opposition groups in Idleb due to the fact that other opposition groups “allowed Turkey to enter Syria.”

Armed opposition groups removing heavy weapons from Idlib disarmament zone on October 10, 2018. Image courtesy of Anadolu Agency.

Internal divisions within Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham have profound implications for the future of the disarmament zone specifically, and the political landscape of northwestern Syria more broadly. Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham remains the largest armed opposition group in northwestern Syria and, through its Salvation Government project, continues to govern nearly all of northwestern Idleb. On the one hand, if Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham is seen as cooperating too closely with the Government of Turkey or Turkish-backed opposition groups, the hardline jihadist component of the group may defect to more hardline groups within the ‘Wa Harad Al-Mumineen’ operations room; on the other hand, if Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham fully rejects the agreement and thereby forces a confrontation with Turkish-backed armed groups, it may also witness defections from its more moderate and local Syrian supporters (and many of the Syrian technocrats within the Salvation Government). In fact, these internal divisions appear to have already had an impact on the ground in northwestern Syria: high numbers of assassinations continue to occur in opposition-held northwestern Syria, many of which have targeted foreign Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham leaders (for more information, see Point 9 in the Whole of Syria Review). Yet, it would also be a mistake to underestimate Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham’s resilience and capacity for organizational survival, especially in light of past attempts by international actors to disaggregate moderate and extremist armed groups in northwestern Syria. As recently explored by Sam Heller in an article published in War on the Rocks, Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham has consistently maintained its dual internal identities of a revolutionary Syrian opposition organization, and a larger, jihadist movement; Hay’at Tahrir Al Sham understands its surroundings and how to square its jihadist character with its Syrian opposition context. Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham has survived internal disputes and defections before, has demonstrated its military and political prowess repeatedly and, more importantly, has shown itself to be an effective governing body through its affiliated Salvation Government. Therefore, the ultimate fate of the disarmament agreement will likely hinge on the ability of Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham to yet again navigate internal demands for pragmatism with its ideological and revolutionary foundation.

Nasib Border Crossing

As of October 24, the Nasib-Jaber border crossing continues to witness heavy commercial and civilian transit. Between October 16 and October 22 nearly 1,750 Jordanians and 550 Syrians have used the crossing to enter Syria, with 641 Syrians using the crossing to enter Jordan; of note, this number does not include the extremely large number of commercial trucks using the crossing. The difference in relative prices between Jordan and Syria, as opposed to returning to Syria, has reportedly been a major motivating factor for individuals using the crossing. Indeed, there are numerous reports of individuals and small businesses using the crossing in order to purchase cheap goods, to include fuel and food, for both personal use and commercial sale in Jordan. For example, one liter of fuel in Syria is ~$0.47 (compared to ~$1.2 in Jordan); one kilo of apples in Syria is ~$0.5 (compared to ~$2 in Jordan); and one liter of olive oil is ~$2 (compared to ~$4 in Jordan). Furthermore, according to the Jordan Trade Room, between ~$1.72 million and ~$2.15 million worth of currencies have been exchanged at the Nasib crossing. Indeed, the extremely heavy traffic has reportedly compelled Syrian and Jordanian officials to begin negotiations to open the Dar’a-Ramtha crossing point in order to alleviate the significant congestion at the Nasib crossing.

The Nasib border crossing between Syria and Jordan was officially opened on October 15. The opening of the crossing came after an agreement between Syrian and Jordanian officials on October 14, which stipulated that: the crossing would be open to both civilian and commercial transit; the crossing would honor the previous Memorandums of Understanding between Jordan and Syria in 1999 and 2009 (which stipulated customs regulations); the crossing would be open from 8 am until 4 pm, regardless of the number of trucks or passengers using the crossing; and that Jordanian citizens may enter Syria with no specific security approvals, while Syrians entering Jordan must provide a security approval and must demonstrate a residency permit or valid visa for their final destination country. The agreement also stipulated that, as the Syrian side of the crossing lacks the requisite equipment, security at the crossing would be handled by the Jordanian side of the crossing. On the Syrian side of the crossing, commercial tolls are to be charged based on the weight of the vehicle and the distance to be traveled; it is worth noting that these commercial tolls are five times higher than the tolls pre-conflict.

Commercial trucks lining on the Jordanian side waiting to enter Syria on 20 October 2018. Image courtesy of Al-7al Al-Souri.

The closure of the Nasib border crossing in 2015 was a devastating blow to the economies of Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon; indeed, even Turkey’s economy was affected by the closure. Prior to the Syrian conflict, Nasib was perhaps the most important border crossing in the entire Levant, functioning as the primary link between Lebanese and Syrian markets with Jordan and the Arab Gulf states. In 2010, $615 million in fees were collected in total (by both Syria and Jordan) at the Nasib-Jaber crossing, and approximately 7,000 commercial trucks used the crossing daily. In the same year, nearly $700 million worth of goods were exported by Syria through the crossing, and $940 million worth of goods were imported into Syria. Indeed, between 2012 and 2015, despite the rapidly expanding conflict, the Government of Jordan had reportedly insisted that the crossing remain open, and reportedly, forbade local armed groups from seizing the Government of Syria positions at the Nasib crossing, despite the relative ease of such a military operation. However, on April 3, 2015 Jabhat Al-Nusra launched a unilateral attack on the crossing itself, subsequently compelling Jordan to pressure Jabhat Al-Nusra into turning the crossing over to Jordanian-supported armed groups.

The closure of the Nasib border crossing not only impacted Syrian and Jordanian markets; as noted, major economic losses were also incurred in Lebanon. According to Nabil Itani, the CEO of the Investment Development Authority in Lebanon, nearly 70 percent of Lebanon’s agricultural exports, 32 percent of its food industry, and 22 percent of its total exports passed through Nasib before its closure. The closure of Nasib devastated Lebanon’s agricultural sector in particular; due to expenses associated with exporting agricultural goods through the ports of Beirut and Tripoli, Lebanon’s agricultural producers were forced to sell their products inside Lebanon at much lower prices, flooding the Lebanese market with cheap produce and impacting the livelihoods of Lebanon’s farmers. According to Raed Khoury, the Head of Lebanon’s Economic Ministry, Lebanese and Syrian officials will meet in November 2018 to discuss logistical issues related to quickly scaling up Lebanese exports to Syria and the Arab Gulf through the Nasib crossing.

More broadly speaking, the opening of the Nasib crossing is a landmark event in the Syrian conflict. In a sense, it marks the start of the ‘legitimization’ of the Government of Syria throughout the wider Middle East. Jordan had prominently supported elements of the Syrian armed and political opposition, while the political environment in Lebanon has been polarized between pro- and anti-Government of Syria parties since the start of the conflict. The fact that both Jordan and Lebanon have engaged with the Government of Syria on the reopening of Nasib indicates that the debate over the stance of both countries towards Syria has been largely resolved, or at least overtaken by more pragmatic concerns. The fact that the economies of all three countries stand to mutually benefit from this trade will likely further solidify the degree to which all three governments will engage in broader cooperation, especially on issues related to the return of Syrian refugees and the status of any future Syrian reconstruction.

Legal Cases Against Former Opposition Figures

On October 10, Samir Shahrour (also known as Al-Minshar), a former armed opposition commander in Liwa Awal (a prominent former armed opposition group in Barzeh and Qaboun), was detained in Barzeh neighborhood by Government Syria Military Intelligence forces; as of October 24, Shahrour remains detained by Military Intelligence. Shahrour, alongside fellow Liwa Awal Commander Muawia ‘Abu Bahar’ Boqai, was the armed opposition commander responsible for the reconciliation of Barzeh in May 2017; Sharhour was subsequently recruited into the NDF and facilitated the reconciliation and NDF recruitment of a large number of Liwa Awal combatants in Barzeh and Qaboun. Shahrour was also a participant in the Sochi National Dialogue conference in January 2018 and was given a medal by the Russian Defence Ministry in April 2018 for his role in fighting ISIS in Hama governorate. Shahrour and ‘Abu Bahar’ also jointly run a business in Barzeh and Qaboun focusing on rubble collection and the provision of construction material.

Muawia Boqai (Abu Bahar) honored by the Government of Syria in November 2017. Image courtesy of Damascus Voice.

The justification behind Sharour’s detention is extremely noteworthy. In early October 2018, Khalil Ta’loubeh, a prominent lawyer in Barzeh, filed a legal case against Shahrour; Ta’loubeh claims that while an armed opposition commander, Shahrour was responsible for killing Ta’loubeh’s brother in addition to two Republican Guard officers in Barzeh in 2012. Ta’loubeh’s case also charges that Shahrour kidnapped the daughter of a prominent Republican Guard officer and raped her prior to ransoming her back to her family in 2013. Reportedly, Ta’loubeh is receiving support in his legal case from Ali Mamlouk, the head of the Government of Syria National Security Office, and the Shalish family, an extremely prominent business family in Damascus.

Shahrour’s arrest is not the only case of a former armed opposition combatant detained due to civilian legal cases filed based on war-time activities. In fact, there are several ongoing court cases that have been filed against reconciled combatants in northern rural Homs by civilians in nearby Alawite villages (to include Kafr Bihem, Rabia, Qabu); these civilian cases reportedly charge reconciled combatants with killings and kidnappings throughout the course of the conflict in northern rural Homs. Similar reports of civil cases filed against former armed opposition combatants have also emerged throughout southern Syria.

Samir Shahrour, center, in front of the reconciliation center

in Barzeh. Image courtesy of Damascus Voice.

A billboard for Abu Bahar’s rubble recycling and

construction workshop. Image courtesy of Al Modon.

Nonetheless, it should also be noted that in Shahrour’s case, there appear to be additional economic interests motivating the detention. The involvement of the Shalish family is noteworthy in light of the fact that Shahrour’s business directly competes with the Shalish family’s interests linked to reconstruction activities in Barzeh and Qaboun. Reportedly Abu Bahar was also recently detained due to disputes surrounding their jointly owned rubble collection business. However, Sharour’s case, as well as the ongoing cases against combatants in northern Homs and southern Syria, highlight a major, often overlooked, factor in reconciliation agreements: while the reconciliation agreement resolves an armed opposition combatant’s status with the Government of Syria, it does not absolve that individual with respect to actions taken during the conflict. In this way, it is likely that further prosecutions will occur against armed opposition combatants for actions taken during the conflict; in a sense, while reconciliation agreements partially resolve the political status of communities and individuals with respect to the State, they are not ‘truth and reconciliation’ agreements, and therefore do very little to resolve existing community tensions, animosity, and antipathy.

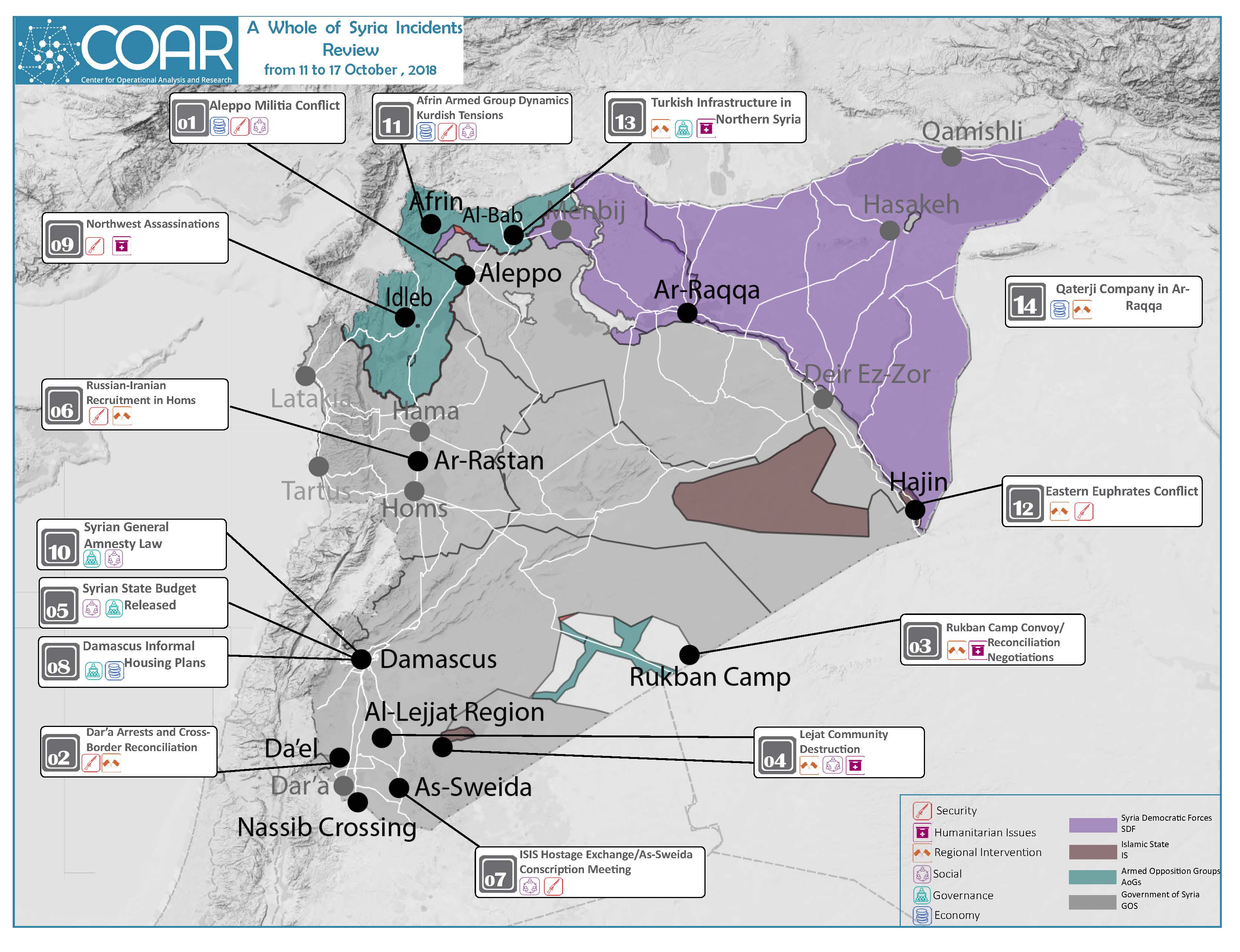

Whole of Syria Review

Aleppo Militia Conflict

Aleppo Governorate, Syria. As of October 22, heavy clashes persist between different pro-Government of Syria militias in eastern Aleppo city and, as of October 21, the Aleppo city police and several other militias have reportedly become involved in the clashes. The Aleppo city clashes began on October 11, when fighting broke out in Bab Al-Nayrab, Marjeh, Salheen, and Karm Houmed neighborhoods of eastern Aleppo city between several Government of Syria aligned militias; namely, the Al-Berri Militia and the Foah and Kafraya Militias. As of October 15, at least 12 individuals have been killed. The clashes began when members of the Al-Berri Militia arrested several members of the Foah and Kafraya Militias; in response to the arrests, the Foah and Kafraya Militias launched a series of attacks against Al-Berri Militia positions.

The clashes between these nominally pro-Government militias have their origins in disputes over real estate. The Al-Berri Militia is one of the most powerful loyalist militias in Aleppo city, and is largely drawn from the Sunni community of Aleppo city and rural Aleppo (particularly from the Jiss tribe). The Al-Berri Militia has significant economic interests in Aleppo city, including in local agriculture, industry, real estate. The Foah and Kafraya Militias are almost entirely comprised of Shiite combatants from Foah and Kafraya, who were evacuated from their communities in July 2018. Following their evacuation, many of the combatants from Foah and Kafraya were given homes in neighborhoods eastern Aleppo city; the majority of these homes had belonged to individuals who were forcibly evacuated by the Government of Syria from the city after the conclusion of the Aleppo city siege in 2016. Given their real estate interests, the Al-Berri Militia believes that they should have economically benefited from the transfer of these homes to the Foah and Kafraya Militia combatants.

By October 18, these clashes expanded to Bashkwi village, east of Aleppo city and the Nabul and Zahraa brigades, also predominantly Shiite Government of Syria militias, joined the clashes on the side of the Foah and Kafraya Militias. On October 21, the Aleppo city police joined the clashes, also on the side of the Foah and Kafraya militias. Many Aleppo residents are concerned that these clashes will expand into a broader sectarian conflict; reportedly, the Al-Bakr Militia, another predominantly Shiite militia in Aleppo city, has begun to provide arms and financial support to the Foah and Kafraya militias. These clashes indicate the deep tensions, both economic and sectarian, between the various pro-Government militias that have assumed control of eastern Aleppo city; these clashes are likely to escalate in the coming weeks.

Dar’a Arrests and Cross-Border Reconciliation

Dar’a Governorate, Syria. Both throughout and prior to the reporting period, there have been numerous reports that the Government of Syria military forces (primarily the Air Force Intelligence Branch) have detained reconciled armed opposition commanders throughout southern Syria. Reportedly, between October 13 to October 22, arrests have taken place in Da’el, Sahm El Golan, Zayzun, Dar’a city, As-Sanamayn, and Ankhal. Among the detained were Mohammed Rashid Abu Zeid, and Mustafa Masalmeh; both were prominent commanders in southern Syria, and following reconciliation, Abu Zeid had joined the Air Force Intelligence, while Masalmeh joined the Military Security Branch. Of note, Masalmeh, also known as Al-Kasim, was reportedly arrested for dealing captagon (an illegal stimulant). However, on October 16, Masalmeh was released by the Military Security Branch. A third former commander, Ayed Al-Khalidi, who joined the Tiger forces, was reportedly killed when Government of Syria forces attempted to arrest him. Also of note, unconfirmed reports from local sources indicate that Jordanian and Russian officials have held ongoing negotiations concerning the return and reconciliation of numerous former armed opposition commanders now located in Jordan. Reportedly, Jordanian representatives are insisting that any commanders who return and reconcile will be stationed along the Jordanian border, and Jordan will assume responsibility for their well being. These developments are indications of two major dynamics: the first is the precarious status of reconciled armed opposition commanders and combatants, even after resolving their reconciliation status with the Government of Syria; the second is that Jordan is at least attempting to maintain its relationships and influence with armed opposition commanders with whom Jordan has worked for the past several years.

Lejat Community Destruction

Lejat, southern Syria. On October 14, Syrian Arab Army forces entered eight villages in the Lejat to include Hosh Hammad, Al-Sahasal, Dahr, Madoura, A’lali, Al-Shomer, Sateh Al-Qadan, and Al-Chyiah. Reportedly, Syrian Arab Army forces used bulldozers to destroy the majority of buildings in these communities and, as of October 22, rubble clearing operations are ongoing. According to the Lejat Media Office, an opposition-oriented social media outlet, the buildings were destroyed to make room for a future Iranian military base, which is reportedly under construction. All of these towns had reportedly been almost entirely depopulated, primarily during the southern Syria offensive in June 2018. While the original residents of these communities are now displaced throughout southern Syria, it is unlikely that they will be compensated or allowed to return to their home villages.

Rukban Camp Convoy/Reconciliation Negotiations

Rukban Camp, southeastern Syria. On October 17, UN Humanitarian Coordinator Ali Zaatari confirmed in a statement that “preparations are actively ongoing for a joint UN/SARC convoy to provide assistance to the estimated 50,000 women, children, and men who are stranded at the Rukban camp…the overall humanitarian situation at the Rukban camp is at a critical stage.” Reportedly, the Government of Syria has given the joint UN/SARC convoy the necessary approvals to reach the camp. According to media sources, between four and fifteen individuals have died in the Rukban camp, in eastern Syria on the Jordanian border, since the start of October 2018. The majority of these individuals have reportedly died due to a lack of food and/or medicine; among them was a 20-year-old girl who died of anemia and malnutrition, and two infant children who died due to a lack of medical care.

The last convoy to reach Rukban was in January 2018, and originated in Jordan; however, Jordanian officials have since repeatedly stated that future convoys should originate inside Syria, as the camp is not in Jordanian territory. Of note, local notables in the Rukban camp have reportedly continued to engage with Government of Syria and Government of Russia representatives to discuss voluntary individual ‘reconciliation’ agreements with the Government of Syria, especially for individuals in need of medical assistance. These discussions are also focused on the evacuation of up to 5,000 individuals (of the estimated 45,000-70,000 individuals currently in the camp) to Turkish-controlled northern Syria. Additionally, according to Russian media sources, “dozens” of individuals in the Rukban camp have been smuggled out of the camp, reportedly for up to $2,000 per person, in order to return to their communities of origin in eastern Homs governorate. A major factor causing these access impediments is the ongoing dispute between the Government of Russia and the U.S. over the status of the Al-Tanf border crossing. Al-Tanf hosts a U.S. military base, and Rukban exists within the Al-Tanf ‘deconfliction zone’; thus, the Government of Russia has repeatedly indicated that Rukban’s status will not be addressed until the U.S. withdraws from the Al-Tanf base. To that end, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Verchinen stated, in an interview with Sputnik news on October 4, that: “[Rukban] is located in the Al-Tanf area, which is illegally controlled by the Americans. The Americans must leave, and until they leave, this camp will remain.” Therefore, the status of the Rukban camp and the dire humanitarian conditions facing its residents are unlikely to fundamentally change in the near term.

Syrian State Budget Released

Damascus, Syria. On October 22, the Government of Syria officially submitted the draft 2019 Syrian State budget to the Syrian parliament. Following the parliament’s approval, the budget will be sent to Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad for approval. The total 2019 Syrian State budget is 3.882 trillion SYP, an increase of 18% from 2018. In the budget, 1.1 trillion SYP will be allocated to ‘investment spending’; 811 billion SYP will be used for ‘social support’, which includes 361 billion SYP for flour subsidies, 430 billion SYP for gas and fuel subsidies, 10 billion SYP for the ‘agricultural production fund’, and 10 billion SYP for the national fund for social assistance. A further 50 billion SYP was allocated to ‘new jobs for reconstruction.’

It is important to note that the expanded Syrian budget is not the result of a recovering economy; in fact, it is an expression of the inflationary pressure facing the SYP/USD exchange rate. According to the Government of Syria, the 2019 budget of 3.882 trillion SYP is equal to $8.92 billion (USD); however, the Government of Syria uses an exchange rate of 435 SYP/USD, while the current rate of exchange in Syria as of October 23 is approximately 465 SYP/USD. Therefore, the more realistic 2019 budget is closer to $8.34 billion. It is also worth noting that, according to the Syria Report, Syria’s inflation rate is estimated at between 25% and 30% annually, which will further shrink the real value of the Syrian budget. Therefore, despite the 2019 budget being labeled as the ‘largest budget since the start of the conflict,’ practically the Government of Syria has very little funding available, and certainly what is available is insufficient to address the considerable needs of the Syrian population or the staggering cost of Syria’s reconstruction.

Russian-Iranian Recruitment in Homs

Homs Governorate, Syria. On October 12, according to local sources and local media, the Russian Military Police in northern Rural Homs opened a recruitment center in Talbiseh city, in northern Rural Homs. As of October 23, this center has reportedly received more than 1,000 individual applications. The opening of this center was reportedly facilitated by Manhal Al-Salouh, a former armed opposition commander who is working with the Hmeimim Reconciliation Center. This recruitment center has begun to directly recruit local Syrians into the Russian Military Police. Reportedly the application criteria is that: applicants must be Syrian Army defectors; who have reconciled their situation with the Government of Syria; and who have graduated high school. Reportedly, the Iranian Revolutionary Guard has also established a recruitment center in Eastern Farhaniyeh, also in northern Homs; however, the Revolutionary Guard recruitment center has had relatively few applicants, especially considering that they are offering relatively high monthly salaries (between $300-$400 per month). The establishment of competing recruitment offices are a further indication that the Governments of Iran and Russia are engaged in competition over the recruitment of reconciled armed opposition combatants (particularly Syrian Army defectors); indeed, there were reports of competing recruitment offices and practices in the aftermath of the southern Syria offensive in July 2018.

ISIS Hostage Exchange/As-Sweida Conscription Meeting

As-Sweida Governorate, Syria. On October 21, the Government of Syria reached an agreement with ISIS combatants in eastern As-Sweida regarding the release all of the remaining 21 Druze hostages held by ISIS, in exchange for families of ISIS combatants detained by the Government of Syria. Reportedly, on October 22, at least 17 women and eight children were released by the Government of Syria, and were sent to Qalaat Madiq, in northwestern Hama; also on October 22, ISIS released two women and three children. The Government of Syria and ISIS also agreed to a 3 days ceasefire, and that following the hostage exchange ISIS combatants in eastern As-Sweida will be evacuated to Hajin, in northeastern Syria. This agreement came after a meeting held in As-Sweida city on October 14 between a group of Syrian Arab Army officers originally from As-Sweida and representatives of the Sheyoukh Karama (a local Druze militia group), the Sheyoukh Aql (the Druze religious leadership), and representatives of prominent families in As-Sweida.

At the meeting, the Syrian Arab Army officers proposed that all Druze military-aged males subject to military service requirements join the Syrian Arab Army 1st Corps; according to the officers, this proposal came directly from Maher Al-Assad, the head of the 4th Division and the brother of President Bashar Al-Assad. Of note, the 1st Corps has traditionally been deployed in southern Syria, and have numerous military bases in As-Sweida, Dar’a, southern Rural Damascus, and Damascus. However, the Sheyoukh Karama initially refused this proposal and stated that they will not engage in any negotiations until the release of the remaining Druze hostages held by ISIS in the eastern Syrian desert. For their part, the prominent families of As-Sweida reportedly agreed with the proposal, under the condition that Druze conscripts will only be deployed to As-Sweida. The tenor of these negotiations hint at two broader dynamics: first, the Government of Syria is continuing to apply pressure to the Druze community in As-Sweida to adhere to their conscription requirements, though are willing to grant some concessions to Druze leaders with respect to local concerns. Second, the Druze community in As-Sweida continues to maintain its long-held stance of relative neutrality and autonomy, though under the current Government of Syria state framework.

Damascus Informal Housing Plans

Damascus, Syria. On October 14, Faisal Sorour, a member of the Executive Office for Planning and Budgets in Damascus Governorate, stated in an interview with SANA that Damascus Governorate will begin to conduct a set of organizational plans and studies with respect to informal housing (ashwaiyat) areas in Damascus. Reportedly, as of October 22, the first of these studies has already begun. In total, there will be five studies: the first study will include Jobar, Barzeh, Qaboun and Mazzeh 96 (all in eastern Damascus), and will be completed in January 2019. The second will include Tadamon, Def Al-Shouk, and Hay Zohour (all in southern Damascus), and will be completed in August 2019. The third will include Dummar, Hay Wurud, and Rabwe (all in northwestern Damascus), which will be completed at the end of 2020. The fourth will include the neighborhoods of the ‘Qasioun mountain’ (in northern Damascus) and will be completed in 2021. The final study will include Madamiyet Elsham, Mazzeh, and the outskirts of Darayya (all in southeastern Damascus), and will be completed by 2023. Effectively, by conducting these studies and organizational plans, Damascus Governorate intends to create a full development and city expansion plan to include all of these neighborhoods and informal settlements. These studies will have deep implications for the housing, land, and property rights of individuals living in or displaced from these neighborhoods. Though speculative, it is unlikely that the Damascus Governorate plans to validate the ownership claims to informal housing and indeed many of these areas are likely to fall under the provisions of Law 10, which has strict stipulations on how Syrian citizens can claim property rights.

Northwest Assassinations

Opposition-held Northwestern Syria. Throughout the reporting period, a large number of assassinations and kidnappings continue to be recorded throughout opposition-held northwestern Syria, largely targeting different armed opposition commanders affiliated with nearly every armed opposition group in northwestern Syria, as well as local humanitarian workers, civil society activists, local council members, and civilians. Between October 1 and October 22, at least 12 Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham commanders have been assassinated, all of them shot by unknown assailants, and the large majority of those assassinated were foreign (i.e not-Syrian) commanders. The most prominent of those assassinated Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham commanders was Abu Yousef Jezrawi, a Saudi commander who was responsible for the personal security of Abu Mohammad Joulani, the leader of Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham. Similarly, at least five commanders from different National Liberation Front groups have been assassinated, nearly all of them killed by explosive devices; the most prominent of these is Abul Aleem Abdullah, the Supreme Shari’ (religious leader) of Faylaq Al-Sham. Furthermore, four humanitarian workers were assassinated (to include the leader of the Ghiras Association, Abu Hamza Homsi); all of the humanitarian workers were also killed by explosive devices. Additionally, 10 humanitarian workers have been reportedly kidnapped, from numerous humanitarian organizations; of note, on October 21, one of the kidnapped humanitarians escaped and reportedly claimed that he was kidnapped by members of Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham. In total, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, between April 26 and October 22, nearly 373 individuals have been assassinated in northwestern Syria. This wave of assassinations and kidnappings further highlights the deep uncertainty and internal instability throughout northwestern Syria, largely caused by the lack of clarity regarding the ultimate trajectory of the northwestern Syria disarmament zone, and the sheer number of competing armed opposition groups (for more information, see the analysis in the top section of this document).

Syrian General Amnesty Law

Damascus, Syria. On October 9, the Government of Syria ‘Official Newspaper’ released the text of Decree 18, which provides for “a general amnesty for all penalties” for individuals, both inside and outside Syria, who have fled or avoided military service; however, as of October 23, many Government of Syria offices (such as border crossings, local police stations, and courthouses) have reportedly not yet received the official documents (namely, the revised lists of wanted individuals) as part of Decree 18’s implementation. In practice, while new decrees are released upon presidential signature in the ‘Official Newspaper,’ they can take months to fully implement as individual offices must receive the required paperwork by mail before full implementation. According to Decree 18, individuals who have avoided military conscription inside Syria have been given four months to resolve their status; individuals outside Syria have been given six months. Of note, this amnesty will only cover individuals who are not guilty of “serious crimes” or “terrorist acts.” With the passage of this law, individuals who had avoided military service may now resolve their conscription status; however, while amnesty provisions in Decree 18 may compel some individuals inside Syria to resolve their status and willingly conscript, it is unlikely that individuals subject to conscription outside Syria will take up the amnesty offer. Therefore, while the new amnesty law has been presented as a potential pull factor for returns to Syria, in practice it will likely have little impact on returns; in fact, Decree 18 may become a deterrent to return, as after a six month-period, the penalties for avoiding conscription will likely be even more severe than previous punishments.

Afrin Armed Group Dynamics/Kurdish Tensions

Afrin, Aleppo Governorate, Syria. On October 21, Sultan Murad, a Turkish-backed armed opposition group operating in Afrin and northern Aleppo, has reportedly prevented Kurdish farmers in the village of Barafa from harvesting olives in the fields outside the village. Reportedly, these farmers will not be allowed to tend to their olive orchards unless they pay Sultan Murad a 30% levy on the total value of their olive harvest. In the same time period, Turkish officials opened a new crossing point between Afrin and Rihan, through a village named Hamam. This crossing will reportedly facilitate commercial trade; in order to open the road for the crossing, Turkish-backed armed opposition groups reportedly destroyed several olive orchards in the vicinity of the crossing that were owned by Kurdish IDPs who had fled the area. All of this also comes after heavy clashes from October 10 to October 12 in Afrin city between Ahrar Sharqiyeh and Liwa Al-Mustapha, both of which are also Turkish-backed armed opposition groups. Reportedly, the conflict was centered on disputes over the ownership of houses in Hayy Sena’a, the industrial neighborhood of Afrin city; these houses were formerly owned by predominantly Kurdish IDPs who had fled Afrin, and have been claimed by both groups. Both incidents highlight the significant housing, land, and property concerns of the IDPs from Afrin, the vast majority of which are Kurdish, that fled Afrin during the Turkish-led Operation Olive Branch offensive in January 2018. These concerns, as well as internal disputes between the new ‘owners’ of these properties, are likely to continue for the foreseeable future.

Eastern Euphrates Conflict

Abukamal District, Deir Ez-Zor Governorate, Syria. On October 21, U.S. coalition forces launched an airstrike on Al-Susa, a village in northeastern Syria approximately three kilometers north of the Abukamal border crossing. The airstrike reportedly destroyed the Othman Bin A’fan mosque in Al-Susa. According to Colonel Sean Ryan, a spokesman for the U.S. coalition, the mosque was being used as a military base by ISIS, and that the airstrike killed 12 ISIS combatants. However, according to numerous local media sources, to include Marsad Souri and Enab Baladi, the actual death toll of the airstrike was nearly 70 individuals, many of whom were civilians. Shortly following the airstrike, on October 22, the SDF reportedly took control of Al-Susa. The conflict between the SDF and ISIS, alongside numerous U.S. coalition airstrikes, has been ongoing on the eastern bank of the Euphrates River since September 11, 2018, as part of the last phase of the ‘Jazeera Storm’ offensive. The Jazeera Storm offensive aims to clear ISIS from its last remaining pockets east of the Euphrates River, particularly from the town of Hajin. It is likely that the Jazeera Storm offensive will continue in the coming weeks; however, considering that this is the last ISIS pocket in eastern Syria, there exists an elevated likelihood of high civilian casualties.

Turkish Infrastructure in Northern Syria

Northern Aleppo Governorate, Syria. On October 22, the Government of Turkey announced the opening of Mare’a hospitals in northern Aleppo. This is the third hospital opened by the Government of Turkey in the past three months; hospitals have also been established in Al-Bab and Ar-Ra’ee. All three hospitals are reportedly well stocked, fully staffed, and contain modern equipment. Out of the three hospitals, the Al-Bab hospital is the largest, with a capacity of 200 beds and eight surgery rooms, with 275 staff. All hospitals were reportedly fully funded by the Turkish health ministry. This is not the only case of the Government of Turkey directly establishing infrastructure in the ‘Euphrates Shield’-controlled areas of northern Aleppo. For example, in August 2018 the Government of Turkey announced the establishment of a new university in Jarablus, which would act as a branch of Gaziantep University (GU). Furthermore, Turkey has also opened Turkish post offices throughout Jarablus, Ar-Ra’ee, and Al-Bab, which also provide banking services. Additionally, much of northern Syria is connected to the Turkish electricity network, and Turkish telecommunications companies are the primary telecommunications provider. Turkey also established a courthouse in Ar-Ra’ee in October 2018, which sits under the authority of the Wali (governor) of Gaziantep. The establishment of individual pieces of infrastructure and service provision networks in Turkish-controlled northern Syria are not noteworthy events in and of themselves. However, when viewed holistically, it is increasingly clear that the Government of Turkey is embarking on a project of statebuilding, or indeed, state incorporation. The fact that much of this new infrastructure is established directly in coordination with or under the authority of Turkish line ministries further emphasizes this point. It is likely that the Government of Turkey will continue to embed Turkish state institutions into local governance bodies and service provision entities in northern Syria for the foreseeable future.

Qaterji Company in Ar-Raqqa

Ar-Raqqa Governorate, Syria. On October 19, the SDF reportedly allowed trucks belonging to the Qaterji Company to enter Ar-Raqqa governorate, using the Tishreen – Al-Qobar road, in order to purchase cotton from local farmers. Of note, members of the Qaterji family, to include Mohammad and Hussam Qaterji, were named on the U.S. Treasury Department sanctions list in September 2018; parts of the Qaterji company itself were also noted on the sanctions list. The Qaterji Company is one of the largest private companies in Syria and was heavily involved in oil and fuel trading with ISIS when the latter controlled northeastern Syria. The Qaterji Company still has considerable influence in the oil and fuel sector, as well as the wheat sector, in northeastern Syria. The fact that the Qaterji company is still operating in northeastern Syria is noteworthy in light of U.S. influence in the region.