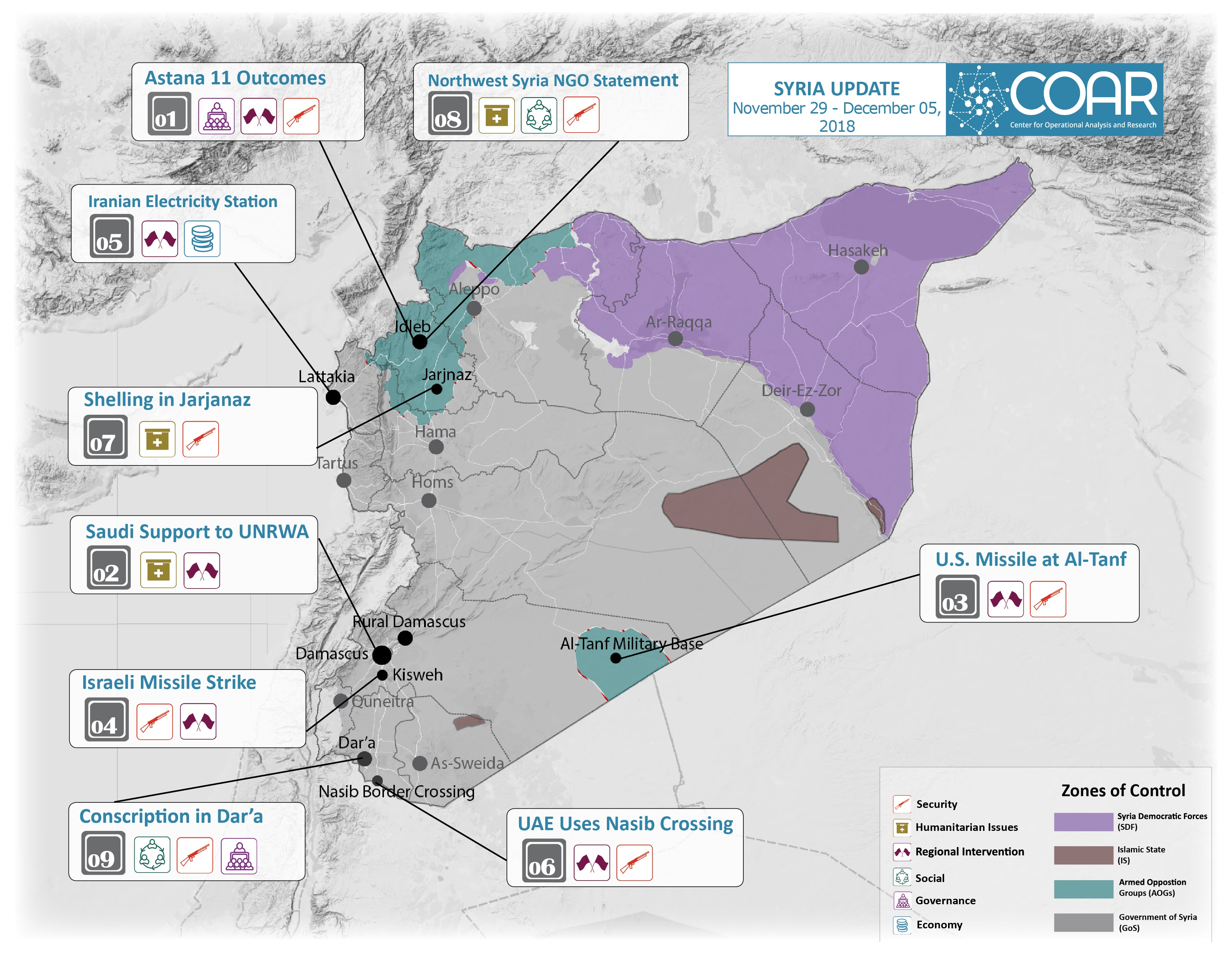

Syria Update

29 November to 05 December, 2018

The Syria Update is divided into two sections. The first section provides an in-depth analysis of key issues and dynamics related to wartime and post-conflict Syria. The second section provides a comprehensive whole of Syria review, detailing events and incidents, and analysis of their respective significance.

The following is a brief synopsis of the in-depth analysis section this week:

On November 26, the Government of Syria issued Presidential Decree 360 and Legislative Decree 19, which stipulate the replacement of nine ministers and the dissolution of the Ministry of Reconciliation respectively. While ministerial reshuffling is itself unremarkable, the timing of Decrees 360 and 19 is intriguing and hints at the Government of Syria’s post-conflict plans. Just as the creation of the Reconciliation Ministry in 2012 marked the beginning of the Government of Syria’s reconciliation strategy, by which the Government of Syria later seized the vast majority of opposition-held areas, the dissolution of the Reconciliation Ministry indicates that the era of reconciliation agreements – and its efficacy as a tactical military strategy – has largely ended. Indeed, there are no longer any easily reconcilable areas, as the remaining territories outside the Government of Syria’s control are under the direct influence of regional and international actors. Nonetheless, while the reconciliation strategy was conceived and initially implemented through the Reconciliation Ministry, the Ministry itself was never a key actor in the implementation of reconciliation agreements; rather, local negotiators and intermediaries always drove these agreements, and in most cases the role of these intermediaries is as strong as ever, and in some cases formalized, in the post-reconciled space.

The following is a brief synopsis of the Whole of Syria Review:

-

On November 29, the Astana 11 talks concluded; the key takeaways from Astana 11 are the survival of the northwestern Syria disarmament agreement and the confirmation of plans for the new constitutional committee, essentially solidifying the legitimacy of Sochi conference outcomes.

-

A U.S. missile strike near Al-Tanf targeted either Government of Syria-affiliated armed actors or ISIS forces; contradicting sources cite both organizations as targets. The incident highlights the unique, and precarious, position of the Al-Tanf military base in eastern Syria.

-

Saudi Arabia increased funding to UNRWA, partially filling funding gaps created by the Trump administration’s decision to withdraw funding. Saudi Arabia is increasingly supplanting U.S. funding to humanitarian and stabilization bodies, likely in coordination with U.S. foreign and domestic policy objectives.

-

Alleged Israeli missile strikes targeted Syria for the first time since a Russian warplane was downed in September 2018 off the coast of Lattakia city, highlighting the complex geopolitical relationships between Israel, Russia, Syria, Iran, and Lebanon, playing out within the context of the Syrian conflict. Reportedly, the missile strikes targeted Iranian Revolutionary Guard and Hezbollah warehouses in southern Rural Damascus.

-

Commercial trucks from the UAE traveled through the Nasib border crossing for the first time in three years, underscoring the apparent political rapprochement between the UAE and the Government of Syria.

-

The Government of Syria’s Ministry of Electricity announced the construction of a large-scale electricity plant in Lattakia city, which is to be funded by the Government of Iran. Iran’s funding of the project underscores the continued Russian and Iranian investment in Syria’s development, and the potential rivalry between the two states in Syria post-conflict.

-

Heavy shelling continued in Jarjanaz, theoretically in ‘retaliation’ for the alleged November 2018 Aleppo chemical attack. Continued shelling by Government of Syria forces jeopardizes the continued disarmament zone agreement, confirmed during Astana 11, and further illustrates the Government of Syria’s discomfort with any resolution short of absolute territorial sovereignty.

-

The Syrian NGO Alliance issued a statement condemning the continued targeting, detention, and kidnapping of humanitarian workers in northwestern Syria, and included a veiled accusation against Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham. While this statement may force Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham to accommodate local humanitarian organizations in the short terms, the organization is unlikely to change its policy with respect to neutral and impartial service provision bodies.

-

The Government of Syria began a conscription campaign, to be initially carried out by local notables and reconciled commanders in Dar’a governorate, emphasizing the function of local notables and reconciled combatants as the primary intermediaries and implementers of state policy in southern Syria.

Minister Reshuffling and Reconciliation

Ministry Closure

In Depth Analysis

On November 26, the Government of Syria issued Presidential Decree 360. Decree 360 will replace nine different Ministers, to include the ministries of Interior; Water Resources; Interior Trade and Consumer Protection; Tourism; Education; Higher Education; Public Works and Housing; Industry; and Communication and Technology. On the same day, the Government of Syria also issued Legislative Decree 19, which dissolved the Ministry of Reconciliation. Notably, the former mandate and responsibilities of the Ministry of Reconciliation will fall under the newly formed ‘National Reconciliation Council’, which sits under the Prime Minister’s Council. Of note, the reshuffling that took place after the defection of Prime Minister Riad Hijab in August 2012 was much larger and more comprehensive.

The timing of this ministerial reshuffling and the dissolution of the Reconciliation Ministry speaks to the present circumstances and outlook of the Government of Syria; indeed, Syrian and Russian-affiliated media have presented Decree 360 as a “preparation for the next phase, after the end of the Syrian crisis.” The cabinet reshuffle also comes at a time when the Syrian conflict is effectively stagnant, largely due to the fact that all the remaining potential points of conflict in Syria are now intrinsically linked to regional and international actors and their accompanying interests. Opposition-held northern Syria is firmly under the influence, and indeed direct control of the Government of Turkey, following the Turkish military’s Euphrates Shield and Olive Branch operations, while much of opposition-held northwestern Syria exists under the framework of Turkish-Russian Disarmament Zone agreement. While the Disarmament Zone Agreement itself is precarious, the recent Astana 11 talks confirmed its status, thereby preventing a major Government of Syrian ground offensive. The U.S. military is itself present in SDF-held northeastern Syria, and has strongly indicated its willingness to defend the Kurdish Self Administration against external aggression. Therefore, with the potential exception of northwestern Syria, national-level political negotiations such as at Astana and Geneva will likely dictate future political developments in Syria.

Indeed, the ministerial reshuffle reflects this reality. The majority of the new ministers are technocrats, and the focus of their ministries is reportedly to be oriented toward addressing the conditions of a post-war Syria, in particular reconstruction and rehabilitation. However, the appointment of Muhamad Khaled Al-Rahmoun as the Minister of Interior may be a noteworthy outlier, as Al-Rahmoun’s appointment could be interpreted as a statement that western considerations and associated sanctions will not deter or even inform Government of Syria decision-making. Notably, Al-Rahmoun is personally sanctioned by the U.S. and the EU for his reputed role in the Eastern Ghouta chemical attack in 2013, while Head of the Political Security Branch.

Indeed, the ministerial reshuffle reflects this reality. The majority of the new ministers are technocrats, and the focus of their ministries is reportedly to be oriented toward addressing the conditions of a post-war Syria, in particular reconstruction and rehabilitation. However, the appointment of Muhamad Khaled Al-Rahmoun as the Minister of Interior may be a noteworthy outlier, as Al-Rahmoun’s appointment could be interpreted as a statement that western considerations and associated sanctions will not deter or even inform Government of Syria decision-making. Notably, Al-Rahmoun is personally sanctioned by the U.S. and the EU for his reputed role in the Eastern Ghouta chemical attack in 2013, while Head of the Political Security Branch.

The former minister of reconciliation with the Russian military responsible for east Ghouta negotiations, during the announcement of releasing Jayish Islam hostages, February 2017. Image courtesy of Enab Baladi

The closure of the Reconciliation Ministry is perhaps the most interesting of these developments, and worthy of further examination, especially with respect to the role and purpose throughout the conflict. In June 2012, as conflict in Syria escalated considerably, the Government of Syria formed the Ministry of Reconciliation and appointed Ali Haidar as the head of the ministry; Haider was a prominent leader of the Syrian Socialist Nationalist Party, which acts as a Government-approved ‘opposition’ party. In late 2012, the Ministry of Reconciliation, in coordination with Government of Syria military and security branches, first crafted a ‘reconciliation’ policy. This policy differentiated between ‘reconcilable’ and ‘non-reconcilable’ armed opposition combatants, and facilitated their surrender and subsequent remobilization, or their relocation to other armed opposition-controlled areas. Local governance bodies were also dissolved, and their staff either evacuated or reconciled; new local governance bodies were then created with new membership and often a larger mandate and number of responsibilities. Between June 2012 and late 2016, more than 70 Syrian communities reconciled under this model, the large majority in rural areas in Tartous, Lattakia, Hama, and Homs governorates. The first reconciliation agreement was in fact in Baniyas, Tartous, following an incident in which pro-Government militias killed between 77-145 Sunni residents of the city. The reconciliation strategy gained traction, and reached its apex with the reconciliation and evacuation agreements negotiated throughout eastern Aleppo city, Rural Damascus, Eastern Ghouta, southern Syria, and northern Homs; by this point, reconciliation had become synonymous with surrender for besieged opposition-held communities. The formal establishment of the Reconciliation Ministry is evidence that reconciliation was by no means an ad hoc strategy of securing control or an outgrowth of local truce agreements, but rather a carefully crafted strategy with its origins in the earliest stages of the conflict.

In many ways, the process of reconciliation defined the Syrian conflict from 2016 to 2018, though as more of a military tactic than a political process. The closure of the Reconciliation Ministry and the reallocation of its responsibilities to the Prime Ministers Council marks a new phase in the Syrian conflict, and signals that the era of reconciliations has largely ended. As noted above, there are no further areas that can be easily reconciled without the acquiescence of major regional and international actors, with the possible exception of the Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham-controlled areas of northwestern Syria. However, it is important to note that, while the reconciliation strategy was born at and initially implemented through the Reconciliation Ministry, the Ministry itself was never the key negotiator in reconciliation agreements; that role always falls to local intermediaries, local military commanders, and indeed, Russian representatives. While future reconciliation agreements are unlikely, the role of local negotiators, and locally negotiated agreements, remains as strong as ever.

Whole of Syria Review

Astana 11 Outcomes

Astana, Kazakhstan: On November 29, the Governments of Russia, Turkey, and Iran released a joint statement, which details the outcomes of the 11th round of Astana talks. Among other points, the three guarantor states expressed concern over violations of the September 17 disarmament zone agreement, and stated that they will “[enhance] the work of the Iranian-Russian-Turkish Coordination Center.” Additionally, the guarantor states reaffirmed their determination to eliminate all armed groups affiliated with Al-Qaeda and ISIS from Syria. The statement also condemned the use of chemical weapons in Syria – likely in reference to the alleged Aleppo city chemical attack on November 24 – and demanded that the OPCW should be the main authority to investigate the use of chemical weapons in Syria. With regards to the constitutional committee, the three states will reportedly increase joint efforts to launch the committee in accordance with the Syria National Dialogue Conference that took place in Sochi in January 2018. In response, the U.S. Department of State released a statement on November 29, indicating that the 11th round of Astana did not yield any significant outcome regarding an agreed list of members for the constitutional committee. The statement additionally accused the governments of Russia and Iran of using Astana to “to mask the Assad regime’s refusal to engage in the political process.” Former UN Special Envoy to Syria, Staffan de Mistura, also stated that he “deeply regrets that there was no tangible progress in overcoming the ten-month stalemate on the composition of the constitutional committee,” adding that the three guarantor states had “missed an opportunity.”

Analysis: Although the statement released by the Governments of Russia, Iran and Turkey indicates that Russia and Turkey will continue to maintain the disarmament zone agreement in northwestern Syria, the agreement itself remains fragile. Critically, Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham remains solidly in control of half of northwestern Syria, and is clearly excluded from the disarmament zone. More importantly, the Astana guarantor states indicated that they will abide by the formation of the constitutional committee in accordance with Sochi conference; during the conference, participants agreed that the constitutional committee would draw on a pool of 150 names put forward by Turkey, Iran and Russia, and that each country would nominate 50 names. However, many Syrian opposition figures, as well as western governments, decried the talks themselves, as there was no substantial Kurdish participation, and indeed, the ‘opposition’ members present were largely considered to be only comprised of opposition members acceptable to the Government of Syria. Therefore, should the constitutional committee move forward on the terms of the Sochi conference, its ultimate legitimacy will continue to be called into question.

Saudi Support to UNRWA

Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: On November 28, the head of the King Salman Humanitarian Aid and Relief Centre, Abd Allah Arabi’a, announced at a press conference in Riyadh that Saudi Arabia has provided $50 million to fund UNRWA. This funding is expected to only partially cover the funding gaps faced by UNRWA following the Trump administration decision to cut funding on August 31, 2018, after previously freezing $300 million in UNRWA funding in January 2018. Previously, the U.S. had been the largest financial supporter of UNRWA, and had provided nearly 33% of UNRWA’s funding. In response to these funding cuts, UNRWA stopped distributing regular humanitarian assistance to Palestinian refugees in Syria on November 12, instead focusing only on emergency cases.

Analysis: The U.S.’ funding cuts to UNRWA have already had an impact on UNRWA’s capacity to support Palestinian refugees in Syria, Lebanon and Jordan. The significant complications of other UN agencies’ ability to respond to Palestinian refugees, given the centrality of UNRWA’s mandate in this regard, has also heightened concerns that Palestinians in Syria will not receive adequate humanitarian assistance. Indeed, Saudi Arabia’s recent financial contribution is expected to lessen UNRWA’s funding challenges; according to a UNRWA statement, UNRWA now only has a $21 million deficit. While the donor states themselves do not have direct influence on programs themselves, Saudi Arabia’s increased involvement in humanitarian funding, particularly for initiatives previously funded by the U.S. withdrawals, is noteworthy. For example, Saudi Arabia is also funding development and stabilization programs in SDF-controlled northeastern Syria, providing $100 million of the $230 million frozen by the Trump administration. Saudi Arabia is likely undertaking these funding measures as a means of further solidifying its relationship with the Trump administration; however, the increased role of Saudi funding will naturally increase Saudi Arabia’s leverage in Syria. It remains unclear how and to what extent is Saudi Arabia will utilize this leverage, but its recent decisions indicate that similar trends of increased Saudi funding to supplant U.S. funding is expected to continue for the foreseeable future.

U.S. Missile at Al-Tanf

Al-Tanf Military Base, Homs governorate, Syria: On December 3, Government of Syria-affiliated SANA news agency released a statement accusing the U.S.-led coalition of launching a missile at Government of Syria military positions south of Sokhneh, in eastern rural Homs governorate. Allegedly, the U.S.-led coalition missile strike occurred after Government of Syria forces crossed into the 55 km deconfliction zone in Al-Tanf, in southeastern Homs governorate. On the same day, the spokesperson for the U.S.-led coalition Colonel Sean Ryan issued a statement, denying the accusation and claimed the attack targeted ISIS military positions. The attack reportedly resulted in the death of a prominent ISIS commander, Abu Al-Umarayn, who was reportedly responsible for the 2014 execution of Peter Kassig, an American humanitarian worker.

Analysis: Despite statements by both Government of Syria-affiliated news outlets and the U.S.-led coalition, it remains unclear whether the coalition missiles were indeed targeting Government of Syria positions or ISIS locations in Al-Badiya. However, the incident is noteworthy, as it highlights the unique position of the Al-Tanf base in Syria. In 2017, U.S. forces established a 55km deconfliction zone in Al-Tanf, in eastern rural Homs governorate, to serve as a training point for armed groups engaged in counter-ISIS operations. Notably however, Al-Tanf has since gained importance as U.S. objectives in Syria have shifted to the removal of Iran from Syria; the Al-Tanf crossing has been presented by many analysts in Washington D.C. as a key military facility to counter Iranian-affiliated influence and presence due to the base’s location at the Al-Tanf crossing point. This is argument is questionable, for while Al-Tanf does theoretically link Damascus to Tehran, through Baghdad, Government of Syria forces are already in control of the Abukamal border crossing, and indeed, Iran has had open access to Syria through the Damascus airport for several years. It is also noteworthy that the Rukban refugee camp lies within the 55km deconfliction zone, and it is likely that the future of the Rukban camp itself is closely tied with the status of the U.S. military base in Al-Tanf. Notably, Russian and Syrian government officials have claimed that the U.S. is responsible for impeding assistance to Rukban on several occasions, highlighting the controversial presence of the nearby Al-Tanf base and the surrounding deconfliction zone.

Israeli Missile Strike

Kisweh and Harfa, Rural Damascus Governorate, Syria: On November 28, the Government of Israel reportedly launched a series of missile attacks targeting locations in Kisweh and Harfa towns, in south and southwestern Rural Damascus governorate. On November 29, Government of Syria media outlets reported that the Syrian Air Defense intercepted a “hostile target” (likely referring to an Israeli warplane) in the vicinity of Kisweh, south of Damascus city; however, these media reports were retracted the next day, and subsequent Government of Syria media reports have only stated that Israeli missiles were intercepted. Reportedly, the Israeli strikes targeted Iranian Revolutionary Guard and Hezbollah warehouses in Kisweh and Harfa; Hezbollah and Iran have denied that any Hezbollah or Iranian positions were targeted. Notably, Government of Russia-affiliated media outlets reported that Syrian Air Defense have not yet used the S-300 missile systems provided by Russia in October 2018 to intercept missile attacks.

Analysis: The alleged Israeli missile attack would mark the first Israeli attack in Syria since the the downing of a Russian warplane, mistakenly shot down by Syrian air defense off the coast of Lattakia on September 17, 2018. It is worth noting that the downing of the Russian warplane was a major catalyst in the Government of Russia’s decision to outfit Syria with the S-300 missile system which, alongside Russian diplomatic pressure, many analysts believe has impacted the ability of Israel to launch airstrikes and missile attacks in Syria. Israel’s primary security concerns are related to the presence of Iranian proxy groups in Syria (including Lebanese Hezbollah), specifically that Iran will have the capacity to easily transport weapons to Hezbollah in Lebanon. The fact that Israel is potentially no longer able to launch regular strikes in Syria has highlighted another major concern that Israel will focus more of its attention on combat Hezbollah and Iran in neighboring Lebanon. To that end, reports on December 4 that the Israeli military intends to conduct operations on the Lebanese border to “expose” Hezbollah’s tunnel network have been met with great concern, considering the potential for an expanded conflict between Israel and Lebanon.

Iranian Electricity Station

Lattakia city, Lattakia Governorate, Syria: On November 27, the Government of Syria Ministry of Electricity announced that it will establish a major electricity station in Lattakia city in early 2019, with financial support of the Government of Iran. The project was reportedly designed in October 2018, when the Government of Iran reached an agreement with the Government of Syria to establish a 450-Megawatt electricity station at the cost of approximately $460 million. The Minister of Electricity, Zouhair Kharboutly, stated that the Ministry of Electricity has finalized the budget, and that the new electricity station in Lattakia will be eco-friendly and will reduce electricity shortages in Lattakia city and rural Lattakia.

Analysis: It is increasingly clear that the Government of Iran intends to heavily invest in Syria’s post-conflict development, rehabilitation, and reconstruction. This is not unusual or unexpected, however, investments in Syria’s infrastructure, especially by the Governments of Iran and Russia, are always noteworthy. As noted in previous COAR weeklies, the Government of Russia and Russian companies are heavily investing in Syria’s infrastructure, as well as its public and private companies. In general, Russian and Iranian investment and development support tends to focus on either basic economic infrastructure (such as roads, water networks, and electricity), or on raw resource production and processing facilities. Despite the close relationship of Iran and Russia on broader Syria policy, there are numerous indications that both governments are rivals in terms of maintaining influence in Syria; thus, Russian and Iranian economic and development agreements are likely to become significant points of leverage and perhaps tension in a post-conflict Syria.

UAE Uses Nasib Crossing

Nasib, Dar’a governorate, Southern Syria: On December 2, media reports indicated that three trucks originating in the UAE traveled through the Nasib border crossing to transport commercial detergent products to Lebanon; these were the first trucks from the UAE to pass through Syria in more than three years. This comes after reports from mid-November 2018 indicating that the UAE intends to begin normalization of diplomatic relations with the Government of Syria; to that end, the UAE is reportedly conducting maintenance on its embassy in Damascus and UAE companies are reportedly offering Syrian nationals short-term tourist visas to the UAE. In a November 18 statement, the Government of Syria’s Deputy Foreign Minister Faisal Mekdad also expressed that the Government of Syria welcomes Arab state initiatives to strengthen ties with Syria.

Analysis: The increased trade through Nasib border crossing is expected to revitalize diplomatic and political relations between Government of Syria and other Arab countries, primarily Lebanon, Jordan, and the Gulf States. The UAE will likely seek to increase its investment and economic ties with Syria, especially with respect to potential reconstruction roles for UAE companies. Notably, the economic relationship between Syria and the UAE has traditionally been reciprocal, as upper-middle class Syrians have invested in the UAE’s economy prior to the beginning of the Syrian conflict. However, it is important to note that rapprochement between the Government of Syria and the UAE is closely tied to Saudi Arabia and U.S. relations; the UAE is unlikely to dramatically depart from the foreign policy objectives of its primary allies. However, the UAE and the Government of Syria do share common concerns with respect to the Muslim Brotherhood; therefore, there are some geopolitical grounds for a rapprochement between the UAE and Syria.

Shelling in Jarjanaz

Jarjanaz, Idleb, Northwestern Syria: Between November 29 and December 4, Government of Syria forces have continuously shelled and launched missile attacks on several areas in southern Idleb governorate, most significantly in Al-Tah and Jarjnaz, theoretically located within the September 17 disarmament zone in northwestern Syria. Notably, on November 25, the Government of Russia conducted a series of airstrikes on Jarjnaz in response to the alleged chemical attack in Aleppo city on November 24. As of December 1, media sources reported that more than 5,000 families have so far been internally displaced from Al-Tah and Jarjnaz due to the shelling; the majority reportedly intend to fled to areas in northern Idleb governorate, to include the Turkish border.

Analysis: The initial Government of Russia airstrikes on Jarjnaz were in response to the alleged chemical attack on Aleppo city, and likely indicate that continual Government of Syria shelling of Jarjanaz is justified by the presence of armed groups in Jarjanaz responsible for the chemical attack. However, it is worth noting that Jarjanaz is approximately 77 km from Aleppo city – far outside the range of most mortar and artillery systems. This shelling also comes after Turkey and Russia reconfirmed their commitment to the disarmament agreement at Astana 11. The continued shelling of Jarjanaz might be viewed as a deliberate, albeit theoretically justified, provocation likely to result in armed opposition group retaliation, thereby undermining the terms and intent of the agreement. While the agreement itself is unlikely to collapse immediately, this incident does highlight the continued difficulty associated with implementing agreements that conflict with the interests of parties to the conflict, in this case the Government of Syria’s wartime objectives.

Northwest Syria NGO Statement

Northwestern Syria: On December 3, the Syrian NGO Alliance issued a statement condemning what it calls the “systematic targeting of humanitarian aid workers in northwestern Syria.” The statement strongly condemned the recent increase of kidnapping and detention of humanitarian workers in the area, holding “local civil and military authorities” responsible for these attacks. It is worth noting that the statement specifically cited the detention of members of the Ataa Humanitarian Relief Society (AHRS). At least 10 members of the AHRS were reportedly kidnapped and detained by Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham in October 2018, and while some of the members were released, several others remain in detention. The statement further demanded and called on “local authorities to…stop any interference by any party in the course of humanitarian action or the freedom of those who are responsible for it.”

Analysis: Kidnappings and targeted assassinations are common in northwestern Syria, targeting civilians, combatants and armed groups, as well as humanitarian actors. However, systematic targeting of the humanitarian and civil society actors has increased since October 2018; indeed, the recent assassinations of Raed Al-Fares and Hamoud Jneid were recent and high-profile examples of this phenomenon. In total, 92 civilians, many of whom were humanitarian workers, were killed in targeted assassinations in northwestern Syria between April and November 2018. While the NGO Alliance statement did not explicitly accuse any specific entity of these attacks, it is clear the the statement is directed at Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham. Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham is known for regular interference in beneficiary lists, the confiscation of humanitarian aid, and the forced inclusion of Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham-affiliated staff within local humanitarian assistance organizations, especially in areas in which it maintains a strong military presence. It is worth noting that Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham has previously been receptive to demands made by humanitarian organizations in order to maintain programs in areas it controls; Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham revocation of its decision to enforce taxes on vehicles transporting humanitarian aid in September 2018 is a good example of such accommodations. However, Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham’s control over civil and humanitarian affairs has always partially hinged upon its willingness to use violence. Therefore, it is unlikely that Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham will fundamentally change its approach to humanitarian and civil society organizations despite recent NGO statements and protests.

Conscription in Dar’a

Dar’a Governorate, Southern Syria: On December 2, the Government of Syria began a major conscription campaign throughout Dar’a governorate. Reportedly, Government of Syria representatives shared community-specific lists of individuals wanted for conscription throughout Dar’a governorate; the lists were given to local notables and the commanders of reconciled armed groups. These local notables and reconciled armed group commanders are reportedly responsible for ensuring that individuals wanted for conscription are informed and conscripted. Additionally, numerous checkpoints have been deployed throughout Dar’a city in an effort to apprehend men eligible for conscription; reportedly, between December 2 and December 4, more than 70 individuals have been conscripted.

Analysis: Conscription campaigns are common throughout Syria, and are especially common in reconciled areas, where most young men eligible for conscription have not fulfilled their military requirements. However, the recent conscription campaign in Dar’a city is noteworthy in that the Government of Syria has ‘outsourced’ the work of identifying men eligible for conscription to local notables and local reconciled commanders. This likely highlights how the Government of Syria intends to govern reconciled southern Syria through a carefully selected group of local intermediaries and reconciled armed opposition combatants; as in many reconciled areas, ‘trusted’ local notables and reconciled combatants are likely to remain the primary intermediary for Syrian state policy in reconciled locations.

The Wartime and Post-Conflict Syria project (WPCS) is funded by the European Union and implemented through a partnership between the European University Institute (Middle East Directions Programme) and the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR). WPCS will provide operational and strategic analysis to policymakers and programmers concerning prospects, challenges, trends, and policy options with respect to a conflict and post-conflict Syria. WPCS also aims to stimulate new approaches and policy responses to the Syrian conflict through a regular dialogue between researchers, policymakers and donors, and implementers, as well as to build a new network of Syrian researchers that will contribute to research informing international policy and practice related to their country.

The content compiled and presented by COAR is by no means exhaustive and does not reflect COAR’s formal position, political or otherwise, on the aforementioned topics. The information, assessments, and analysis provided by COAR are only to inform humanitarian and development programs and policy. While this publication was produced with the financial support of the European Union, its contents are the sole responsibility of COAR Global LTD, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.