Political Demographics

The Markings of the Government

of Syria Reconciliation Measures in

Eastern Ghouta

Political Demographics

The Markings of the Government

of Syria Reconciliation Measures in

Eastern Ghouta

30 December, 2018

Executive Summary

In late March and early April 2018, opposition-held communities in Eastern Ghouta reconciled with the Government of Syria following a large-scale offensive, which targeted every community in the formerly besieged and opposition-held pocket. Reconciliation agreements are not a new development in the Syrian conflict; however, Eastern Ghouta marked the first reconciliation agreement covering a densely populated and geographically large area. [footnote] Some would contend that the Aleppo city ‘reconciliation’ in December 2016 also covered a densely populated area. However, eastern Aleppo city is not geographically large. Eastern Aleppo city was a collection of several different neighborhoods of Aleppo city, while Eastern Ghouta was a collection of numerous distinct communities, with different armed actors and zones of control, and distinct community relationships with the Government of Syria. [/footnote] Over the course of the Eastern Ghouta offensive, the Government of Syria militarily divided the region into three pockets, and the predominant armed groups in each pocket subsequently negotiated independent reconciliation agreements with the Government of Syria.

Much has changed in Eastern Ghouta in the eight months following the implementation of the Eastern Ghouta reconciliation agreements, much of it very relevant for policy-makers and programmers. This pa-per employs case studies that examine post-reconciliation dynamics in the largest communities in each of the reconciled pockets of Eastern Ghouta, namely Duma, Arbin, and Harasta, and identifies key trends and conclusions relevant to future humanitarian, development, and stabilization programs and policy. This report was compiled over the course of several months, and relies on both publically available data as well as key informant interviews with current and former residents of these communities.

Based on an analysis of Duma, Harasta, and Arbin, it is apparent that the Government of Syria seeks to increase control over areas and populations formerly governed and controlled by the armed opposition through a process socio-political engineering and selective localization. This strategy is premised on the identification and division of communities and residents into ‘controllable’ and ‘uncontrollable’ cat-egories, and subsequently implemented through the application of a policy of selective returns based on strict security procedures, the (s)election of trusted local governance leadership, and the deliberate prioritization of service provision and rehabilitation projects.

In practice, this strategy acts as a form of socio-political engineering that reinforces the presence of ‘con-trollable’ populations through the prioritization of scarce resources to their communities, empowers a new class of proven local intermediaries and functionaries, and simultaneously penalizes or neglects ‘uncontrollable’ populations through impediments to return and a lack of support. The policies and practices implemented in post-reconciliation Eastern Ghouta should be considered as a possible model for the reincorporation of formerly opposition-held communities throughout Syria.

Introduction

Throughout the Syrian conflict, there have been frequent instances in which humanitarian assistance was instrumentalized by parties to the conflict in order to achieve political and security ends.[footnote] For example, see the investigative articles published by the Guardian regarding aid impartiality in Syria.[/footnote] While lamentable, this phenomenon is also in many ways unavoidable, as service provision, political legitimacy, and state security in an asymmetrical conflict environment – are in many ways inextricably linked.[footnote] U.S. Government Counterinsurgency Guide. “The economic and development function in COIN [Counter Insurgency] includes immediate humanitarian relief and the provision of essential services such as safe water, sanitation, basic health care, livelihood assistance, and primary education, as well as long-term programs for development of infrastructure to support agricultural, industrial, educational, medical and commercial activities.” https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/119629.pdf [/footnote] Yet even as armed conflict ebbs, the significance of the interlinkage between services, security, and politics remains paramount; political and security objectives take a new form while essential services are eclipsed by development and reconstruction plans and goals.

The Russian intervention in Syria marked the beginning of the end for the armed and political opposition. Communities that had previously been besieged for several years began to surrender, one after another, through the application of what has been euphemistically termed the Government of Syria’s ‘reconciliation’ strategy. [footnote] For more information on these dynamics, please see the work of the Mercy Corps Humanitarian Access Team, specifically “The Local Impact of Reconciliation Agreements: A Preliminary Assessment”, authored by Max Gardiner, Hani Al-Telfah, Madeleine Thomas and Peter Luskin. [/footnote] In the spring of 2017, three of the largest remaining armed opposition-held areas, Eastern Ghouta, southern Syria, and northern rural Homs, reconciled. The Government of Syria’s apparent victory through military force, rather than political negotiations, means that many of the initial grievances and drivers of the conflict remain unaddressed. In the case of ‘reconciled’ communities, there has been no tangible peace and reconciliation process, but rather the reimposition of state sovereignty through more traditional means.

Trapped between power, ideals, traditional morality, and practical humanitarian necessity, the international response to the Syrian crisis continues to walk on eggshells. Conflict sensitive and ‘do no harm’ approaches are increasingly difficult to implement within the context of such a protean political and military environment. The arguments presented in this paper therefore seek to cast light on the logic and dynamics that shape reconciled areas, recognizing that the basis of well-informed decisions, whether by policy-makers or practitioners, is solid information and thoughtful analysis.

Findings

Eastern Ghouta fell to the Government of Syria in March 2017. At present, the Government of Syria is in the process of reincorporating these formerly opposition-held communities and reimposing sovereignty. Based on an analysis of three communities in Eastern Ghouta – Duma, Harasta, and Arbin – the Government of Syria seeks to align assistance and development, local governance, security, and political strategies in order to reinforce ‘passive’ forms of social control upon which it – and arguably any government – relies.

Political Demographics

One of the premises explored in this paper is the existence of ‘controllable’ and ‘uncontrollable’ population. The classification of indigenous people by an external analyst is fraught with methodological, ethical and reputational risks; that risk only increases when categories are loosely defined and politically-informed. That said, the ‘controllable’ versus ‘uncontrollable’ framework is germane to the Syrian conflict, and reputational risks to the analyst are balanced by the very real risks associated with external interventions, regardless of the degree to which altruism is a motivating factor.

In the context of reconciled areas, ‘controllable’ refers to individuals who have passed strict Government of Syria security vetting procedures, as explored below, and have thus been permitted to return to their community of origin. As noted by multiple local key informants, the large majority of those receiving security approvals to return to formerly opposition-held communities in Eastern Ghouta had displaced in much earlier stages of the conflict. Indeed, the very act of fleeing the armed opposition and actively choosing to remain in Government of Syria-held communities is politically significant and is understood to be a key defining characteristic of ‘controllable’ populations currently returning to Eastern Ghouta. Critically however, this does not mean that ‘controllable’ populations are necessary active supporters of the Government of Syria; rather, demonstrations of loyalty required the passive acceptance of the Government of Syria and its associated systems, proven through the act of displacing to and subsequently residing in Government of Syria-held areas during the conflict.

Dr. Lisa Wedeen explores this concept of passive acceptance and social control in pre-conflict Syria in her article Acting ‘As If’; Wedeen argues that social control and ‘trustworthiness’ in Syria is not necessarily built on strongly-held beliefs and fealty, but rather on the idea that by “acting as if they do [believe]…[Syrians] thus confirm the system, fulfill the system, make the system, are the system.” [footnote] Wedeen, Lisa. “Acting ‘As If’: Symbolic Politics and Social Control in Syria.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 40, no. 3 (1998): 503-23. http://www.jstor.org/stable/179273. [/footnote] Thus, ‘controllable’ populations are not necessarily hardcore loyalists, but instead a population that the Government of Syria perceives as controllable, and who in turn ‘act as if’ by buying into passive forms of social control and accepting the status quo Syrian state system. [footnote] Two others phenomena identified by key informants, but not addressed directly in this paper, also illustrate the unique relationship between social and political identity with respect to controllable populations in Syria. The first is that many returnees to Eastern Ghouta rely on informal connections (wasta) in order to facilitate security permissions; indeed, paid wasta networks have reportedly formed in many IDP communities to facilitate this process for individuals who do not personally have access to these networks. In this way, easy access to necessary contacts needed to facilitate the return to Eastern Ghouta, especially from April to July 2018, characterizes belonging within a ‘controllable’ social group. Second, and paradoxically, is the fact that many of the controllable population no longer have a sense of social belonging to communities in Eastern Ghouta, and thereby have little interest in returning. In some cases, this is a consequence of the political stigma attached to Eastern Ghouta; in many other cases, this is based on security and service concerns, recent marriages and businesses, destruction of homes, and a variety of other reasons. [/footnote]

Who Returns?

The first and primary method of securitization is through controls imposed on returnees to reconciled communities in Eastern Ghouta. In the cases of Duma, Arbin, and Harasta (and indeed all of previously opposition-held Eastern Ghouta) lists of individuals wishing to return must be approved by the Government of Syria’s National Security Office, headed by Ali Mamlouk; those few individuals that pass this vetting all share a common characteristic: political trustworthiness as demonstrated by having lived in Government of Syria- eld communities during the besiegement and thereby having already passed relevant security checks[footnote] It is worth noting that the strict security checks in all three communities reportedly need final approval from the National Security Office; in a sense, this means that the approvals required to return come from the highest levels of the Government of Syria’s security structure. There is more information on each community’s security vetting process in the detailed section on each community below.[/footnote] One key example of this phenomenon is the case of Harasta city: following the reconciliation of Harasta, nearly the entire population of opposition-held Harasta city was either evacuated or displaced to IDP camps in Government-held areas. As of October 31, 2018, the total population of Harasta city is 1,095 people, which includes 711 returnees. [Footnote] As of October 1, according to UN and local NGO partners, there were approximately 1,095 individuals living in Harasta, 711 of whom were returnees. It is important to note that two neighborhoods of Harasta were consistently under Government of Syria control; the majority of those individuals who remained in Harasta lived in these neighborhoods.[/footnote] What is notable is that returnees to Harasta are almost entirely former residents of Harasta city who had fled when the armed opposition took control of the city, and had previously resided in Government-held areas. Of the roughly 19,000 IDPs who fled during the final stages of the siege, very few – if any – have received those security permissions necessary to return. Recent returnees, which comprise the overwhelming majority of the current Harasta population, are thus considered ‘controllable.’

This phenomenon extends beyond Harasta city: neighboring Arbin and Duma also experienced significant displacement throughout the conflict, and at present security permissions are reportedly only extended to former residents who displaced to Government of Syria-held areas following the armed opposition takeover; however, Arbin and Duma experienced less displacement as a percentage of total population, and therefore the proportion of ‘vetted returnees’ is lower and the ‘controllable’ population is less, relative to Harasta city. In the case of Arbin, Government of Syria local intermediaries have also reportedly begun to actively encourage ‘controllable’ populations to return; for example, key informants reported that much of the Christian population that fled Arbin between 2011-2014 to Government of Syria-held areas have recently been encouraged to return to Arbin with the approval and coordination of both religious officials and the National Security Office.

Who Serivces?

Perhaps most notable is how service provision and future rehabilitation plans have been distributed across all three of the recently reconciled communities. In all three areas, services such as water, electricity, and road networks remain largely nonfunctional. While there is some limited rehabilitation work ongoing, it is largely insufficient and in early stages; however, in both Duma and Arbin the courthouse, police station, municipal offices, and civil registries have been rehabilitated, while there are comparatively little significant efforts to rehabilitate water and power networks.

It is also noteworthy that of the three communities examined in this report, the most significant rehabilitation work thus far has been in Harasta city, which has the lowest total population of all three communities [footnote]All numbers are provided by UN and local NGO partners. Yet when discussing the population of Harasta city, it is important to note that considerable discrepancies exist with respect to population data between various sources. UN and local NGO partners note that there are 1,095 individuals living in Harasta city (as of October 31, 2018). However, according to the Harasta city council, there are 22,000 individuals living in Harasta; reportedly, this number was derived by security officials counting individuals crossing checkpoints. SARC also reportedly claims that there are 17,000 individuals in Haratsa; it is unclear how this number was obtained. Finally, the Harasta city Mukhtar reportedly stated that there are 12,500 individuals in Harasta; he bases this number off of legal documentation and certificates of residency. Some of the discrepancies likely arise due to the large number of individuals living in nearby Dahiet Elasad (167,621 according to UN and local NGO partners), some of whom are originally from Harasta and who may have been counted as currently living in Harasta. This discrepancy may also be due to more malign intentions. Nonetheless, COAR has chosen to use UN and local NGO partners data on account of their robust methodology, and past reliability and accuracy. [/footnote]with 1,095 total inhabitants compared to 40,811 in Duma and 13,342 in Arbin. [footnote] All numbers are provided by UN and local NGO partners, and are as of October 31. [/footnote] Additionally, Harasta city also has comparatively more ongoing, longer-term UN and INGO projects focused on rehabilitation and development and has seen more investment (reportedly encouraged by the Government of Syria) from the Damascus business community. According to one Government of Syria official,[footnote] According to a local source interview with Government of Syria officials in the Rural Damascus governorate office. [/footnote] Harasta has been prioritized due to its role as part of the greater Damascus rehabilitation plan and a key entry point into reconstructing Damascus’ suburbs.

One might argue, however, that Harasta has been selected as an anchor, and thus receives greater rehabilitation and resilience support, due to its relatively high proportion of ‘controllable’ inhabitants. Currently, approximately 65% of Harasta is comprised of returnees, a much higher percentage than in any other community in Eastern Ghouta. The fact that a community of 1,095 individuals is receiving a disproportionate amount of reconstruction and rehabilitation support, when compared to far more densely populated communities, hints at the Government of Syria’s broader strategy of prioritizing returns and associated services in communities populated by ‘controllable’ inhabitants.

Who Governs?

In terms of local governance, all three communities possess a similar dynamic: the Government of Syria intends to defer to a pre-selected trusted local intermediary class to engage in decentralized local governance. On September 16, the Government of Syria held national-level local elections throughout Syria. While there were nominally ‘independent’ candidates in local elections across Syria, Baath party candidates won the majority of seats in communities examined in this paper. What is notable is not necessarily the success of the Baath party, but rather the profiles of those victorious local candidates, whether on Baath or independent election lists. The vast majority of victorious local election candidates in those communities germane to this paper fall into two categories: first, a Government of Syria-oriented local elite, consisting primarily of members of prominent families deeply involved in local business (historically allied with Government of Syria leadership) and individuals closely linked to the upper echelons of Baath party leadership; and second, technocrats affiliated with various line ministries. [footnote] Examples of victorious candidates can be found below, in the detailed sections on each community. [/footnote] In fact, in several cases, candidates had previously been involved in or even dominated cross-line trade structures throughout the siege of Eastern Ghouta siege, while others members of the reconciliation committees in their respective cities.

Effectively, the war-economy business class and the local Baath party elite will now become the local governing class; it is likely that the technocrats will be responsible for what rehabilitation does take place, while trusted local business and political intermediaries will govern and act as intermediaries to enforce the Government of Syria’s control over the local community.

Who Secures?

At present, the groups responsible for securing communities in Eastern Ghouta are either highly trusted Syrian military units or proven and controllable pro-Government militias originally from the area. This is the case in many other reconciled areas; the deployment of local groups, consisting predominantly of individuals who fled to Government of Syria-held areas during the besiegement, speaks to the Government of Syria’s strategy of working through pre-selected, and controllable local intermediaries, under the supervision of larger institutions. The Republican Guard and the 4th Division, both considered elite Government of Syria military units, are stationed in all three communities. Local militias and armed groups also form a component of local security forces in all three communities. For example, in the case of Duma, one of the primary security forces is Jaish Al-Wafaa, an NDF unit nominally under the aegis of the Republican Guard. [footnote] It is worth noting that Jaish Al-Wafaa also took part in the Eastern Ghouta offensive. [/footnote] Jaish Al-Wafaa is almost entirely comprised of combatants originally from Eastern Ghouta, who had remained loyal to the Government of Syria throughout the conflict and fled to Damascus in the early stages of the conflict. Similarly, the Harasta NDF is composed of former Harasta residents who had fled in 2012, though are currently based in neighboring Dahiet Al-Assad (2km away) following accusations of looting.[footonote] It is also worth noting that in early May 2018, at least 4,000 former armed opposition combatants and civilians reconciled with the Government of Syria and joined Government of Syria military forces, subsequently deployed across numerous communities in Eastern Ghouta. Many of these were reportedly former Jaish Al-Islam and Faylaq Ar-Rahman combatants, although exact numbers are extremely difficult to confirm. In all three communities, reconciled former opposition recruits are present; while some have been deployed outside of Ghouta, a component remains within Eastern Ghouta. Therefore, there is a now an originally local body of reconciled combatants that now are affiliated with the Government of Syria securitizing the recently reconciled communities. [/footnote] In effect, in both ‘controllable’ or ‘uncontrollable’ communities, security follows a pattern similar to governance, and relies on carefully-selected local intermediaries as well as formal state security forces.

Conclusion

The Government of Syria appears to be devoting or directing significant resources to the rehabilitation and reconstruction of Harasta. In addition to allowing greater access for humanitarian and development agencies, the Government of Syria is also encouraging the Damascus business community to work and invest in Harasta. Simultaneously, either through a lack of capacity or by design, the Government of Syria is not prioritizing or encouraging rehabilitation work in Duma or Arbin to the same degree, despite the fact that both communities are much more densely populated.

The Government of Syria likely plans to approach reconstruction on a case-by-case; ostensibly, Harasta has been prioritized due to the fact that it is in closer proximity to Damascus city and is a major part of Damascus’ urban plans. The fact that resource distribution and urban revival planning is disconnected from population density and needs speaks not only to the priorities of the Government of Syria, but also its broader reconstruction strategy, which is very likely informed by political and security objectives.

Socio-political engineering, implemented by restrictions on returns, very likely underpins the Government of Syria’s post-conflict security and reconstruction strategy, especially in heavily damaged (and predominately formerly opposition-held) communities. Some may view this policy as collective punishment; others may view this as a means of ‘safeguarding’ investments in Syria’s reconstruction. Given the consistent instrumentalization of international assistance by all parties to the conflict, it should be no shock that security, political, and development interests align. Yet rather than providing fodder for advocacy, this paper seeks to document and analyze dynamics in reconciled areas to inform decision-making.

Post-Reconciliation Case Studies

Harasta, Duma, and Arbin

Since the negotiation of the reconciliation agreements in each opposition pocket, the security, governance, and services environment in Eastern Ghouta has been radically altered. Opposition military, governance, and service provision entities have been largely dismantled and replaced by Government of Syria bodies. However, this was not a wholesale policy of removal and replacement, but rather also included the selective incorporation of ‘reconcilable’ individuals; for example, many armed opposition combatants were not evacuated to northern Syria, but rather incorporated into Government of Syria security forces, reportedly in large numbers. Furthermore, the reconstructed governance and service provision space has clearly been designed to take into account Government of Syria strategic priorities, especially as these relate to returnees and potential reconstruction opportunities. This paper argues that these strategic priorities are largely related to exerting greater control over Eastern Ghouta through a policy of localization built around a new class of trusted local intermediaries, and prioritizing service provision to controllable populations and neglecting those deemed politically uncontrollable.

The following section provides case studies based on a careful examination of security, social governance, and service provision dynamics in three significant communities in Eastern Ghouta: Duma, Arbin, and Harasta city.

Harasta

Harasta city is almost entirely depopulated. Prior to the Government of Syria offensive in Eastern Ghouta during March 2018, there were approximately 24,212 individuals living in opposition-held Harasta city. The March 2018 Eastern Ghouta offensive caused the overwhelming majority of the Harasta city population- nearly 19,000 individuals- to displace to collective shelters and camps; following the reconciliation agreement, an additional 5,204 individuals were evacuated to opposition-held northern Syria. As a result, only 384 individuals resided in Harasta city immediately following the reconciliation agreement.[footnote] It is important to note that two neighborhoods (named Gharb Al-Autostrad) were consistently under Government of Syria control; the majority of the individuals who remained in Harasta and were not evacuated lived in these neighborhoods, as they were not part of the reconciliation agreement. All numbers courtesy of UN and local NGO partners. [/footnote]

Due to the fact that nearly the entirety of the city was evacuated, there were no guarantor provisions in the reconciliation agreement, such as a stipulation requiring the deployment of Russian Military Police. Likely due to the absence of Russian Military Police, Government of Syria military forces, to include the Republican Guard, the 4th Division, and the Harasta NDF (which was largely comprised of former residents of Harasta who fled to neighboring Dahiet Al-Assad during 2012-2013) reportedly looted many of the abandoned homes.[footnote] This practice is commonly referred to as Ta’afeesh; essentially taking spoils of war and selling them in local markets.[/footnote] Subsequently, Government of Syria forces established numerous checkpoints in the vicinity of Harasta, and the Harasta NDF was withdrawn to Dahiet Al-Assad.

Initially following the reconciliation agreement, and partially due to the scale of looting, limited numbers of IDPs were afforded permission to returned to Harasta. However, as of October 31, 2018, 711 IDPs have reportedly returned to the city. [footnote] All numbers according to UN and local NGO partners.[/footnote] According to local sources, most of these returnees had fled the city when it fell to the armed opposition in 2012. Currently, IDPs from Harasta seeking to return must present security permissions issued by National Security Office at checkpoints located outside Harasta. The number of detentions in Harasta is reportedly low, though once again this is likely due to the extremely low population and the displacement of those previously living under armed opposition control.

The entire Harasta opposition local council, like much of the remainder of the Harasta population at the time of the reconciliation agreement, was evacuated to Idleb. Shortly after the agreement, in April 2018, the Government of Syria established the Harasta city council (Majlis Medinat Harasta); reportedly nearly half of the Harasta city council staff were former members of the pre-war Harasta city council, who had fled to Damascus during the conflict and besiegement. The other half were employees of various Government of Syria Ministries, described by local sources as technocrats. Following elections held on September 16, twenty-one of the newly elected Harasta city council members came from the Baath party election list and one is independent.[footnote] The independent is Muhammad Dura, a prominent businessman from Harasta. While nominally independent, Dura is known to be close to prominent members of the Syrian Baath party.[/footnote] All local to Harasta, and come from either prominent Harasta business families and/or closely linked with the Baath party, or are known to be technocrats affiliated with various Government of Syria line ministries.[footnote] For example, one victorious candidate, Ahmad Zeitoun, is a prominent businessman and a member of the Zeitoun family, which has close connections with the Political Security Branch and business ties to Riad Shalish, a business associate and cousin of President Bashar Al-Assad. Another victorious candidate, Mohamad Said Rustum, is related to Mohamad Rustum, a General in the Republican Guard. An example of one of the technocratic representatives is Omar Ali Katkout. Katkout is a civil engineer who left Harasta in the early stages of the conflict and has been working for the Syrian Ministry of Planning; Katkout has a good local reputation as a competent technocrat. [/footnote]

Despite the returning population, as of November 2018, state-run service provision in Harasta remains only semi-functional. Reportedly, the water network only functions in one neighborhood of Harasta city; this is attributed to significant damage to the water pumping stations. Electricity only functions for up to 10 hours per day, and only in the Al-Ajami and old Harasta neighborhoods. Roads networks remain extremely damaged, and there is considerable rubble cleanup required, though the Public Company for Bridges and Roads is currently working to rehabilitate the road linking Harasta to Damascus. The public bus from Harasta to Al-Tell and Harasta to Abasiyeen Square is now running but is reportedly insufficient, and taxi prices remain extremely high. Markets remain largely non-functional, and the majority of individuals living in Harasta use markets in Damascus or Al-Tell. The hospital in Harasta was rehabilitated and is now functional. Additionally, the Government of Syria is reportedly strongly encouraging local businessmen and businesses in Damascus to work and invest in Harasta.

As of November 2018 there are numerous international NGOs, Syrian NGOs, and UN Agencies working in Harasta; projects include school rehabilitation and street cleaning. Compared with more densely populated neighboring communities, Harasta has a disproportionately high number of assistance and rehabilitation projects. Partially, this can be attributed to Government of Syria prioritization of the area. For example, according to the Harasta city council, a meeting was held in July 2018, hosted by the Japanese Consulate to Syria.[footnote] The Harasta city council announcement can be viewed on their facebook page. [/footnote] Representatives from UN agencies and INGOs attended, as well as the head of the Harasta city council, a representative from the Ministry of Local Administration, and a representative from the Rural Damascus Governorate council. At the meeting, plans were reportedly made for the rehabilitation of Harasta; according to the Harasta city council, nearly $1,350,000 was allocated to Harasta, the majority of which from Japan; indeed, on December 5, the Harasta city council announced that this allocation had been increased to $5 million.[footnote] Announcement linked here.[/footnote] Reportedly, several of these projects have already entered implementation. According to Government of Syria officials, Harasta has been prioritized due to the fact that it is seen as the northern ‘gateway’ to Damascus, and is a key component of the Damascus city rehabilitation plan.[footnote] According to local source interview with individuals in the Rural Damascus governorate office.[/footnote]

Duma

Following the negotiation of the reconciliation agreement with Jaish Al-Islam, 19,181 individuals were evacuated to Jarablus and Al-Bab from Jaish Al-Islam-held areas,[footnote] Evacuation numbers courtesy of ACU.[/footnote] to include approximately 8,000 Jaish Al-Islam combatants and roughly 11,000 individuals from the Duma local council, local humanitarian implementing partners, civil society groups, and associated family members.[footnote] According to one local source who worked with the Eastern Ghouta relief office and was evacuated, he was actually offered reconciliation; however, he chose to be evacuated to avoid military conscription. [/footnote] Despite the fact that forced conscription was to be delayed by six months as part of the reconciliation agreement, in early May 2018 the Government of Syria began to conduct regular conscription campaigns in Duma. In tandem with the forcible conscription campaigns, a reconciliation office was established in Duma, and reportedly a number of former Jaish Al-Islam combatants and local civilians who did not evacuate willingly joined Government of Syria military forces.[footnote] As noted above, in early May at least 4,000 former armed opposition combatants and civilians reconciled with the Government of Syria and joined Government of Syria military forces across numerous communities in Eastern Ghouta. Many of these were reportedly former Jaish Al-Islam combatants, however exact numbers are extremely difficult to confirm. [/footnote] Additionally, there are numerous reports of former activists and civil defence workers being detained for ‘investigations’ by security services, particularly Air Force Intelligence; confirming exact numbers of those detained for investigations is extremely difficult.

As of November 2018, the Government of Syria State Security Branch, the Republican Guard, and several NDF units under the oversight of the Republican Guard are now stationed in Duma. Russian Military Police are also semi-regularly present in Duma. It is worth noting that the majority of Government of Syria military forces in Duma are locals, which paradoxically has been a major source of tensions. The majority of the combatants in the largest NDF unit in Duma, Jaish Al-Wafaa, are loyalists who had fled Eastern Ghouta in the early stages of the conflict.[footnote] Ahmad Sarboul, the leader of Jaish Al-Wafaa, is originally from Duma city. His brother is a member of parliament, and a cousin on the recently established Duma municipality. The Sarboul family has been locally prominent in Duma since before the conflict. [/footnote] Reportedly, this group especially has been responsible for many of the reports of local abuses such as looting, harassment, and property confiscation. Additionally, the majority of the former armed opposition combatants and civilians from Duma who joined Government of Syria forces joined the Republican Guard; according to local sources, many of these individuals are still stationed in Duma.[footnote] It is important to note that these reconciled combatants do not reportedly comprise the majority of Government of Syria forces in Duma.[/footnote] The reason why these individuals have not been deployed outside Duma has been attributed to the fact that they must still undergo training, and that the terms of the reconciliation agreement stipulate that they will not be deployed for six months, and have thus not yet been deployed to any major front lines.

Once the model of opposition local governance, Duma’s local representation and governance are similar to other recently reconciled communities. Following reconciliation in March 2018, Duma was governed by a newly established ‘executive committee’, which was largely comprised of technocrats chosen from different line ministries. New representatives for the Duma city council were elected during the national-level local elections on September 16. As in Harasta, the Baath party won the majority of seats on the new Duma city council; twenty-eight individuals came from the Baath party list and eight came from the ‘independent’ list. Also as in Harasta, the majority of these candidates can be grouped into two categories: first, prominent local businessmen and individuals tied to either the upper echelons of the Government of Syria or the Baath party; and second, technocrats affiliated with various line ministries.[footnote] For example, Yasser Adas is the son of Rateb Adas, the Vice-Governor of Rural Damascus governorate (who was also a member of the Duma reconciliation committee). Another example is Memdouh Abd El-Daim; Abd El-Daim ran as an independent, but the Abd El-Daim family (alongside Mohieddine Minfoush and the Hasaba family) were responsible for much of the cross-line trade that took place during the Eastern Ghouta siege. A third successful candidate, Mahrous Ash-Shughri, is most well known as a prominent Syrian singer who ran on the Baath party ticket. Ash-Shughri is well known for his songs praising the Government of Syria and Assad personally; most notably, Ash-Shughri reportedly has close relations with the head of Jaish Al-Wafaa, Mohamad Haj Ali.[/footnote]

As of October 31, there are 40,198 individuals living in Duma, a significant decrease when compared to the November 2017 population estimate of 121,123. Also as of October 31, 4,459 individuals have returned to the city since the end of military operations in Eastern Ghouta. However, the majority of those who have returned are from the temporary shelters outside Duma and returned relatively shortly after the conclusion of the reconciliation agreement; unlike in Harasta, many of those individuals who fled Duma to Damascus between 2012-2014 have reportedly not yet begun to return to Duma in large numbers.[footnote] According to one local source: “Anyone who is not making a problem for the Government, they will be allowed to return. Anyone else, no.”[/footnote]

Services remain largely nonfunctional in Duma city. Water networks are disrupted, though SARC, in partnership with a UN Agency, has reportedly installed several large water tanks in Duma to provide potable water. Access to water remains a significant need and hygiene conditions in the city are reportedly dire, as garbage remains uncollected and there is insufficient water for washing. There is little to no electricity in Duma, and reportedly, there are few, if any, projects rehabilitating water and electricity networks. Additionally, there is extremely limited NGO or INGO activity ongoing in Duma, with the exception of SARC and Syria Trust.[footnote] SARC is supported by the UN on numerous projects across Syria.[/footnote] Road networks linking Duma to Damascus and to southern Eastern Ghouta remain non-functional, which has drastically impacted and disrupted local markets.[footnote]One local source who has not yet been permitted to return to Eastern Ghouta stated the he expects that the Government of Syria intends to only rehabilitate parts of Eastern Ghouta that generate a profit “they will control reconstruction, and they will be benefiting from Eastern Ghouta and its sources of income.”[/footnote] Many of Duma’s inhabitants continue to rely on periodic humanitarian assistance delivered by the UN (or in one instance, the Government of France).[footnote] The Government of France provided a convoy of humanitarian aid, in coordination with the Government of Russia, in June 2018. The convoy contained food, NFIs, and medical aid. [/footnote]

Additionally, many Governmental buildings, to include a courthouse, civil registry, and’ police station are under rehabilitation; the prioritization of these government buildings is noteworthy, and in many ways speaks to Government of Syria’s priorities in Duma.[footnote] That said, twelve schools have been rehabilitated in partnership with the Education Ministry, reportedly with Russian support. A hospital has been rehabilitated, and rehabilitation work is ongoing on the Samaadi road linking Duma city to eastern Eastern Ghouta, as well as roads linking Duma to Harasta. [/footnote The rehabilitation of electrical networks reportedly began in mid-October; however, the rehabilitation plans are reportedly limited to the central electrical grid, and not residential electricity.[footnote] According to one local source, whose home was destroyed: “They [the Government of Syria] destroyed it, but when they rebuild they will probably take it”[/footnote] There are no other known plans to rehabilitate electricity or water networks in Duma, although this may be due to the fact that the newly elected city council has not yet assumed their positions.

Arbin

Similar to Harasta and Duma, Arbin experienced significant displacement following the siege of Eastern Ghouta, and very low levels of returns. Following Faylaq Ar-Rahman’s reconciliation in March 2018, nearly 41,984 individuals were evacuated from Faylaq Ar-Rahman-held areas, to include Arbin.[footnote]Data courtesy of ACU.[/footnote] This number not only included combatants but also the vast majority of local governance officials, humanitarian aid workers, civil society activists, and their families, in Arbin.[footnote]One local source, a Doctor, did note that he was offered the opportunity to reconcile; however, he chose to be evacuated, as he feared retribution from the Government of Syria for having treated armed opposition combatants in the past.[/footnote] As of October 31, there are 13,342 inhabitants in Arbin, a significant decrease when compared to the November 2017 population estimate of 34,950 people; the current population of Arbin reflects a total of 1,891 returnees from Damascus,[footnote]Numbers are courtesy of UN and local NGO partners.[/footnote] with the remaining 33,059 individuals having remained in the area throughout the besiegement and having reconciled their status with the Government of Syria. Shortly after the end of the siege and accompanying reconciliation agreement, the Government of Syria established a police station, a Baath party office, and a municipality.

A reconciliation committee was established in Arbin, and continues to function; the reconciliation committee logs and tracks the names of those individuals who wish to return to Arbin.[footnote]One local source, who was evacuated, stated that while he would like to return to Arbin, he does not expect to ever expect to be allowed to return to his home or property.[/footnote] Much like in other reconciled communities, the lists of individuals wishing to return to Arbin are sent to the Government of Syria’s National Security Office and only ‘vetted’ individuals are permitted to return to Arbin through the Damascus checkpoint.[footnote]The committee is headed by Hassan ‘Askalani, a Baath party official. [/footnote]According to one local source, the National Security Office is more lenient on allowing women and children to return, although only so long as they are unaccompanied by male family members. Also of note, Arbin once hosted a sizeable Christian community. Boutros Lahham, a Christian Orthodox religious figure, has begun to organize many of the Christian IDPs from Arbin in order to facilitate their return with the approval of the National Security Office.[footnote]To that end it is worth noting that Lahham has also led calls for the rehabilitation of churches in Arbin.[/footnote] As noted above, as of September 1, 2018 at least 1,454 individuals are returnees to Arbin (out of a total population of 13,015).

After Arbin’s reconciliation, an ‘executive committee’ was established in Arbin, largely comprised of line ministry affiliated technocrats. Following the September 16 elections, a ten-person city council was elected; seven of the victorious candidates came from the Baath party list, and three are ‘independant’. As in Harasta and Duma, the majority of these candidates can be grouped into prominent local business families, local individuals closely linked to the upper echelons of the Baath party, or technocrats affiliated with different line ministries. For example, one victorious Baath party candidate Nazir Youssef Arbineeya. Arbineeya was a part of the Arbin reconciliation committee, and is also a prominent local businessman. Another is Addeba Baalbeki, a female candidate; Baalbeki won on the Baath party ticket, but is known as a competent agricultural engineer.

Services in Arbin remain largely nonfunctional. According to the Arbin executive committee, only one of the three primary water networks are currently functioning. Electricity is largely non-functional, however, three neighborhoods in Arbin have generator power providing 3 hours of electricity per day. Roads remain largely nonfunctional, with the exception of the road linking Arbin to Damascus, which has been rehabilitated; public transportation remains nonfunctional.[footnote]There are no microbuses running in Arbin, and a private service taxi can run up to 5000 SYP to reach Damascus city.[/footnote] There are several humanitarian agencies working in Arbin, to include SARC, Syria Trust, and several local NGOs and charities. However, in order to receive aid from SARC, many individuals in Arbin must reportedly pass a set of SARC guidelines and paperwork demonstrating that they are indeed from Arbin and living in Arbin.[footnote]According to Arbin Al-Jadeed, a facebook page covering news in Arbin. https://www.facebook.com/1299055436905085/photos/pcb.1428516230625671/1428516190625675/?type=3&theater[/footnote] There have been occasional UN convoys that have reached Arbin since the reconciliation agreement, and there are also small-scale INGO programs.

In general, there is little significant rehabilitation work ongoing in Arbin. That said, as in Duma, the courthouse, police station, municipality, and civil registry are under rehabilitation, again highlighting the Government of Syria’s strategic priorities in Arbin. Further emphasizing these priorities, the Arbin municipality requested approximately 350 million SYP (approximately $750,000) from the Rural Damascus Governorate on June 13 in order to continue to rehabilitate key infrastructure, road networks, and to fund garbage collection; representatives from the Government of Syria reportedly stated that funds were not available.[footnote]According to the Arbin Executive Committee. https://www.facebook.com/orben1922/posts/1738209179620385 [/footnote]According to local sources, the population of Arbin is increasingly frustrated with the Arbin municipality due to the lack of rehabilitation work.

Annex 1: Population Figures[footnote] All numbers courtesy of UN and local NGO partners. Returns as of October 31 indicates the number of individuals who have returned since the end of the Eastern Ghouta offensive on April 8.[/footnote]

[supsystic-tables id=18]Annex II: Timeline – De-escalation, Offensive, and Reconciliation

De-Escalation

At the start of 2017, the dominant political theme of the Syrian conflict was the implementation of the Government of Syria’s ‘reconciliation’ strategy, which involved the surrender and subsequent evacuation of opposition-affiliated actors in most of the besieged opposition enclaves of Rural Damascus; at this time, an Eastern Ghouta offensive appeared imminent. Yet by May 2017, the Astana guarantor states (namely, Turkey, Russia, and Iran) had signed a joint agreement regarding the creation of ‘de-escalation’ areas in southern Syria, Eastern Ghouta, northern rural Homs, and opposition-held northwestern Syria. At this time, Eastern Ghouta was largely divided between two armed opposition factions; Jaish Al-Islam, which was in control of much of northern Ghouta to include Duma city, and Faylaq Ar-Rahman, which was in control of much of southern Ghouta, to include Arbin. Ahrar Al-Sham and Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham also maintained a limited presence in Eastern Ghouta; Ahrar Al-Sham’s was largely limited to Harasta city, and Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham’s presence was limited to Jobar and several communities in southern Eastern Ghouta.

In the early stages, the Eastern Ghouta de-escalation agreement appeared to improve dire siege conditions for civilians in Eastern Ghouta. However, also in May 2017, the neighborhoods of Barzeh and Qaboun, in Damascus, reconciled with the Government of Syria. These two neighborhoods held the most important tunnel networks into Eastern Ghouta; therefore, by taking control of both neighborhoods, the Government of Syria effectively closed nearly every major access point into opposition-held Eastern Ghouta with the exception of the Al-Wafideen formal crossing point, located near Duma city and on the opposition side controlled by Jaish Al-Islam.

By August 2017, the de-escalation agreement had largely broken down, and the Government of Syria began to launch regular airstrikes and shelling attacks into Eastern Ghouta. Furthermore, armed opposition factions, especially Jaish Islam and Faylaq Ar-Rahman, were not only in open armed conflict with the Government of Syria, but also with one another. The failure of the de-escalation agreement was at least nominally attributed to the continued, albeit limited, presence of Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham in Eastern Ghouta. The Government of Syria regularly demanded Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham’s surrender and evacuation to preserve the agreement; however, Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham was largely located in areas controlled by Faylaq Ar-Rahman, which was either unable or unwilling to forcibly dissolve the group.[footnote]Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham was largely present in Arbin, Aashari, and Jobar. Local sources indicate that Faylaq Ar-Rahman was unwilling and unable to force Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham’s evacuation due to the fact that Faylaq Ar-Rahman was dependant on Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham for access to funds from donors outside Syria.[/footnote]

The breakdown of the Eastern Ghouta de-escalation agreement was also partially due to the fact that the Government of Syria was also engaged in continuous but parallel reconciliation negotiations with individual armed opposition groups in Eastern Ghouta. The most notable of these was in Harasta, where the Government of Syria’s Ministry of Local Reconciliation[footnote]The breakdown of the Eastern Ghouta de-escalation agreement was also partially due to the fact that the Government of Syria was also engaged in continuous but parallel reconciliation negotiations with individual armed opposition groups in Eastern Ghouta. The most notable of these was in Harasta, where the Government of Syria’s Ministry of Local Reconciliation conducted extensive negotiations with the Harasta Local Council. Reportedly, a reconciliation agreement was almost finalized in January 2018, when Ahrar Al-Sham launched an offensive from Harasta into Damascus city and captured the strategic Armoured Vehicle Base in Harasta; the offensive was reportedly launched in order to halt the reconciliation negotiations.[/footnote] conducted extensive negotiations with the Harasta Local Council. Reportedly, a reconciliation agreement was almost finalized in January 2018, when Ahrar Al-Sham launched an offensive from Harasta into Damascus city and captured the strategic Armoured Vehicle Base in Harasta; the offensive was reportedly launched in order to halt the reconciliation negotiations.

The Harasta negotiations were not the only reconciliation negotiations taking place at this time. The Ministry of Local Reconciliation, alongside Russian negotiators, were also engaged in parallel negotiations with both Jaish Al-Islam and Faylaq Ar-Rahman. However, it is worth noting that, in general, Jaish Al-Islam was engaged in much more frequent and regular reconciliation negotiations with the Government of Syria.[footnote]This was evidenced by the numerous prisoner swaps and prisoner releases between Jaish Al-Islam and the Government of Syria throughout late 2017 and early 2018.[/footnote] The fact that the Government of Syria appeared to favor reconciling with Jaish Al-Islam was a major source of internal conflict within the armed opposition; therefore, the de-escalation agreement, and subsequent reconciliation negotiations, were largely used by the Government of Syria to promote a strategy of ‘divide and conquer’ within the armed opposition itself.

Escalation in Hostilities in Eastern Ghouta: Spring 2018

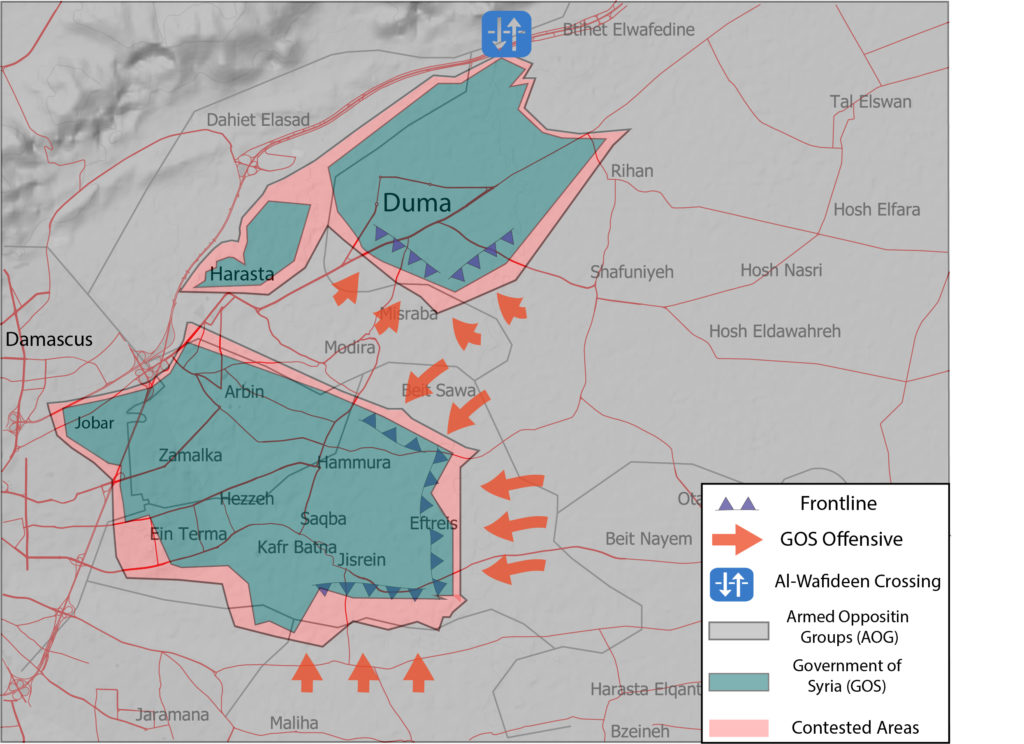

In late February 2018, the Government of Syria launched a major and decisive offensive on Eastern Ghouta. By the start of March 2018, nearly every community in Eastern Ghouta was subjected to heavy, and near constant, airstrikes and shelling, all commercial crossings were closed,[footnote]By this point, the only remaining commercial crossing point was the Al-Wafideen crossing point controlled by Jaish Al-Islam.[/footnote] and humanitarian access and programming had decreased drastically. The Government of Syria subsequently launched a major ground offensive while simultaneously continuing to demand that local armed opposition groups and community leaders reconcile. Most notably, on March 10, Government of Syria forces negotiated the withdrawal of the armed opposition from Misraba, in central Eastern Ghouta; this agreement was largely facilitated by Mohieddine Minfoush, a prominent businessman local to Misraba who was responsible for the majority of the cross-line commercial trade through the Al-Wafideen crossing point. By securing Misraba, the Government of Syria had thus captured nearly half of opposition-controlled Eastern Ghouta, and had separated the area into three pockets: Jaish Al-Islam controlled Duma city, and its outskirts; Faylaq Ar-Rahman controlled Arbin and Saqba, and their outskirts, and Harasta city.

Reconciliation Measures and Effects

Following the division of Eastern Ghouta into three pockets, the Government of Syria began to negotiate individual reconciliation agreements with each opposition-held pocket, thereby creating three parallel negotiations tracks.[footnote]In fact, there were many more localized negotiations; however, these negotiations were generally held in smaller, more marginal communities, many of which had already been taken over militarily. [/footnote]Additionally, on March 4, the Government of Syria established a series of ‘humanitarian corridors,’ which in theory would allow civilians to flee military operations in Eastern Ghouta to camps in the vicinity of Eastern Ghouta.[footnote]According to UNOCHA, by April 22 more than 158,000 individuals were displaced from Eastern Ghouta through these corridors. According to UN and local NGO partners, approximately 30,988 individuals have returned to Eastern Ghouta as of October 31; as will be discussed throughout the paper, these are not necessarily the same individuals that fled the Eastern Ghouta offensive.[/footnote] In practice, and as occurred in Eastern Aleppo, ‘humanitarian corridors’ were also used to justify continued heavy conflict and besiegement.

Harasta (Ahrar Al-Sham)

On March 21, Ahrar Al-Sham reached an agreement with the Government of Russia and the Government of Syria regarding the evacuation of Ahrar Al-Sham combatants and ‘irreconcilable’ civilians from Harasta. The primary negotiators on the Government of Syria side were a Republican Guard officer,[footnote]Reportedly, the Republican Guard officer is a member of the Ismail family, a prominent family from Qardaha, Lattakia, the ancestral home of the Assad family.[/footnote] a Russian military representative, and representatives from the Ministry of Local Reconciliation. The agreement stipulated that all armed opposition combatants were to be fully evacuated to Idleb with their light weapons and that civilians choosing to remain in Harasta would be permitted to stay with guarantees of Russian protection. There is no known publicly available written version of this reconciliation agreement. By March 23, an estimated 5,204 people had evacuated Harasta to Idleb under this agreement.[footnote]All evacuation numbers are courtesy of ACU response coordinators in northern Syria.[/footnote]

Southern Ghouta (Faylaq Ar-Rahman)

On March 24, Faylaq Ar-Rahman also agreed to reconcile communities under its control, namely, Arbin, Saqba, Ein Terma, and Jobar, and the Syrian Arab Army forces subsequently entered these communities. The Government of Syria used numerous negotiators in its agreement with Faylaq Ar-Rahman; in Jobar, the reconciliation was largely negotiated by officers in the 4th Division; the negotiations in the other Faylaq Ar-Rahman-held communities were led by Russian representatives and Suheil Hassan, the leader of the Tiger forces. On the Faylaq Ar-Rahmans side, the lead negotiator was Abul Nasr, the nominal leader of Faylaq Ar-Rahman. As part of its agreement, Faylaq Ar-Rahman surrendered its heavy weapons, identified to Government of Syria forces the locations of tunnels and landmines, and agreed that any combatants and individuals that were unwilling to reconcile would be evacuated to Turkish-controlled northern Aleppo. Ultimately 41,984 individuals were evacuated from Faylaq Ar-Rahman held areas.[footnote]According to the ACU.[/footnote]

The means by which Faylaq Ar-Rahman agreed to the reconciliation was unique. Faylaq Ar-Rahman was comprised of a core armed group, with several other adjacent armed groups nominally affiliated with Faylaq Ar-Rahman. Prior to the official reconciliation, two of these groups, the Majd Brigade and the Ashaari Brigade, negotiated their own individual reconciliations with the Government of Syria, and handed over the communities of Hammura and Ashaari to Government of Syria forces. Additionally, it was revealed after the reconciliation that a prominent religious leader within Faylaq Ar-Rahman, Bassam Defdah, was in fact working on behalf of the Government of Syria to both report on Faylaq Ar-Rahman, and to internally influence Faylaq Ar-Rahman to reconcile.[footnote]Defdah is originally from Kafr Batna and reportedly has linkages to both Suheil Hassan (the lead negotiator of the reconciliation agreement with Faylaq Ar-Rahman), as well as the current Syrian Prime Minister Imad Khamis.[/footnote]

Northern Ghouta (Jaish Al-Islam)

By late March, the only remaining opposition held pocket of Eastern Ghouta was the Jaish Al-Islam held areas in and around Duma city. Jaish Al-Islam had been continuously negotiating reconciliation terms with the Government of Syria. Mohammad Alloush, a delegate to the Astana talks and the brother of former Jaish Al-Islam leader Zahran Alloush, and Issam Bweidani, the leader of Jaish Al-Islam, negotiated the reconciliation from the Jaish Al-Islam side. From the Government of Syria side, Russian representatives reportedly led the negotiations. Between late March and early April, Duma city and its surroundings were heavily shelled and targeted by airstrikes. Despite the fact that reconciliation negotiations had been ongoing for a relatively long period of time, Jaish Al-Islam regularly refused to fully reconcile, and instead insisted that it maintain some presence in Duma, and that elements of the Duma local council were preserved.

On April 7, the Government of Syria was accused of dropping bombs filled with toxic chemicals on Duma city. According to local sources, between 40 and 70 people were killed by these attacks and between 500 to 1,000 were injured. The day after the alleged chemical attack, the Russian Defense Ministry announced that it had reached an agreement with Jaish Al-Islam in Duma, whereby all Jaish Al-Islam-affiliated combatants and their families would be evacuated to either Idleb governorate or northern Aleppo. In further statements made by Syrian state television, the agreement also included guarantees that the Syrian Arab Army would not enter Duma, and that a Russian Military Police presence would guarantee that remaining civilians neither be conscripted nor detained by Government of Syria forces for a period of at least six months.[footnote]Of note, while a written version of the reconciliation agreement must certainly exist, a copy could not be found for this report.[/footnote] In addition, the agreement reportedly stipulated that trade via the Al-Wafideen crossing would be resumed upon the arrival of Russian Military Police, that students would be free to resume their studies upon reconciling their statuses with the Government of Syria, and that Jaish Al-Islam would free all Government of Syria-affiliated detainees. Additionally, the Rural Damascus governorate committee would also enter Duma city, and begin to resolve civil issues, such as recording child births, marriages, and deaths. Ultimately, more than 19,181[footnote]Numbers courtesy of ACU. individuals were evacuated from Duma and northern Ghouta, largely to northern Aleppo.

The Wartime and Post-Conflict Syria project (WPCS) is funded by the European Union and implemented through a partnership between the European University Institute (Middle East Directions Programme) and the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR). WPCS will provide operational and strategic analysis to policymakers and programmers concerning prospects, challenges, trends, and policy options with respect to a conflict and post-conflict Syria. WPCS also aims to stimulate new approaches and policy responses to the Syrian conflict through a regular dialogue between researchers, policymakers and donors, and implementers, as well as to build a new network of Syrian researchers that will contribute to research informing international policy and practice related to their country.

The content compiled and presented by COAR is by no means exhaustive and does not reflect COAR’s formal position, political or otherwise, on the aforementioned topics. The information, assessments, and analysis provided by COAR are only to inform humanitarian and development programs and policy. While this publication was produced with the financial support of the European Union, its contents are the sole responsibility of COAR Global LTD, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.