U.S. President Donald Trump reaches to shake Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s hand before a meeting in New York, September 2017. Photo courtesy of Brendan Smialowski/AFP.

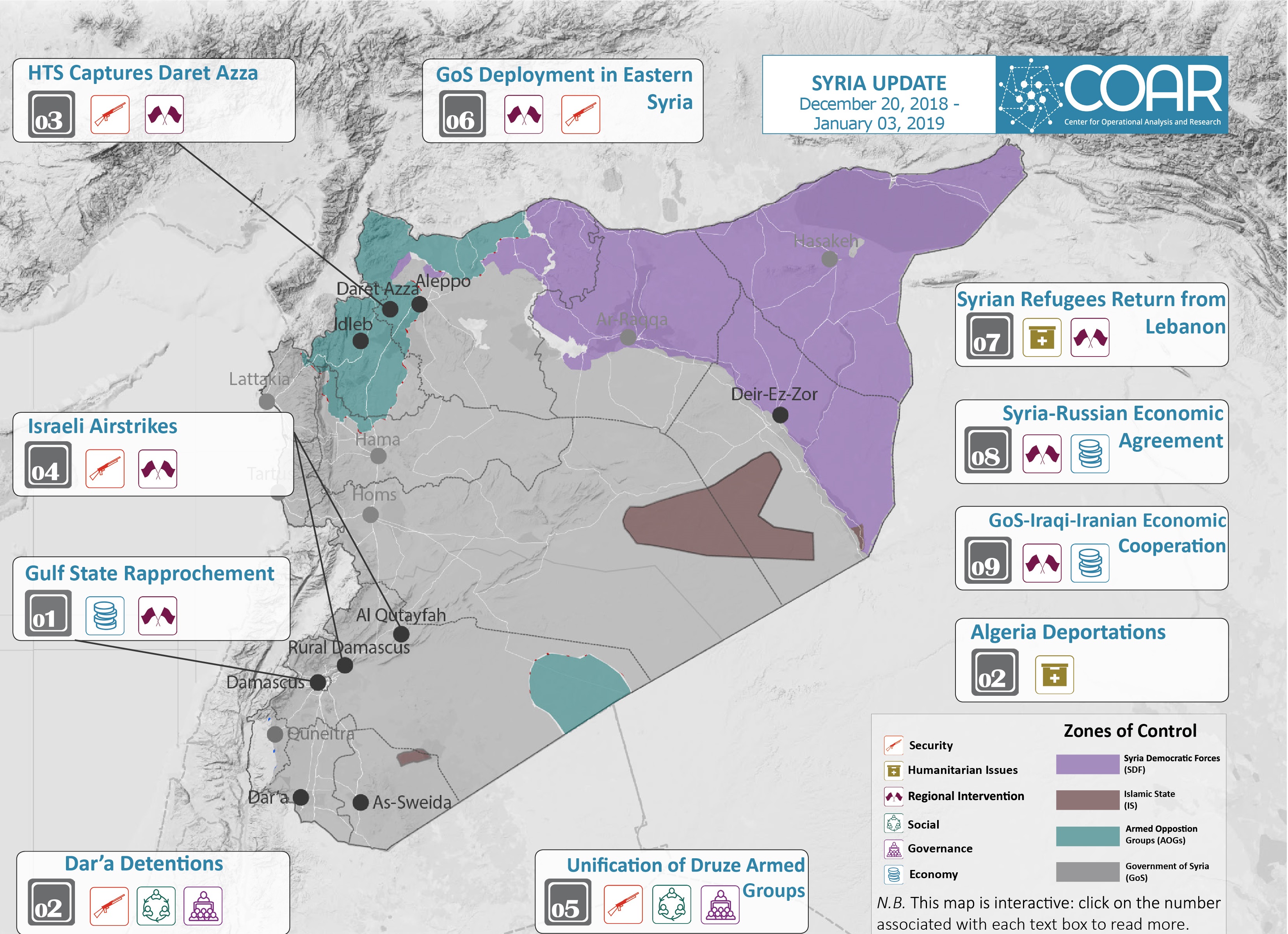

Syria Update

20 December, 2018 to 03 January, 2019

The Syria Update is divided into two sections. The first section provides an in-depth analysis of key issues and dynamics related to wartime and post-conflict Syria. The second section provides a comprehensive whole of Syria review, detailing events and incidents, and analysis of their respective significance.

The following is a brief synopsis of the in-depth analysis section this week:

On December 19, U.S. President Donald Trump announced that the U.S. would withdraw its forces from Syria. The announcement clearly came as a shock to many U.S. officials and U.S. allies, to include the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF); considerable upheaval has occurred following President Trump’s announcement, both within President Trump’s cabinet and in Syria. Some analysts have predicted that the U.S. will not ultimately withdraw from Syria due to the high potential for consequent Syria-specific and regional instability; however, while President Trump’s decision making is clearly unpredictable and erratic, the U.S. decision to withdraw from Syria is grounded in his personal ideology and demonstrates longer-term pragmatism with respect to the U.S.-Turkish relationship. A phased U.S. military withdrawal will therefore likely occur, most probably within the coming 120 days. Regardless of the actual timetable, the impact of the U.S. withdrawal has already been felt on the ground. Government of Syria forces have jointly deployed with the SDF in Menbij and along the Turkish border, while fears of an impending Turkish offensive will accelerate negotiations between the SDF and the Government of Syria. Additionally, the potential for a U.S. withdrawal will likely expose deep tensions between the Kurdish Self Administration and Arab tribes throughout northeastern Syria. Ultimately, as a broader agreement between the SDF and the Government of Syria takes shape, territorial swaps in predominantly Arab areas such as Menbij, Ar-Raqqa, and northern Deir-ez-Zor, will likely occur, as too will the soft reintegration of Kurdish Self Administration administrative structures and bodies into corresponding Government of Syria structures. These events will ultimately have a significant impact on the cross-border humanitarian, development, and stabilization responses in northeastern Syria.

The following is a brief synopsis of the Whole of Syria Review:

- Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham has captured Daret Ezza from the National Liberation Front-affiliated Noureddine Al-Zenki Movement. Turkey is likely to compel Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham to cede control of the town; however, if Turkey fails, a broader inter-opposition conflict in northwestern Syria is extremely likely.

- A series of meetings and statements, as well as the reopening of the UAE embassy in Damascus, indicates that rapprochement between numerous Arab states and the Government of Syria will continue in the near-term.

- Druze armed groups in As-Sweida declared their unification and opposition to Government of Syria conscription practices; while open conflict is unlikely in the near term, it is an indication of the deep tensions between the Government of Syria and the increasingly unified Druze community.

- Approximately 1,000 Syrian refugees have reportedly returned to Syria from Lebanon; the fate of Syrian refugees returning to Syria from Lebanon remains extremely difficult to monitor and confirm, which is compounded by divisions within the Lebanese caretaker government and the outsized role of Lebanese General Security over Syrian refugee returns.

- Israel launched airstrikes in Rural Damascus, using Lebanese airspace; Israel is likely to increasingly confront Iran in both Syria and Lebanon, especially considering the impending withdrawal of U.S. forces from Syria.

- The Government of Syria deployed military forces to eastern Deir-ez-Zor to combat ISIS, likely due to the fact that the SDF is unlikely to continue prioritize fighting ISIS due to the impending U.S. withdrawal from Syria.

- The Government of Syria has negotiated separate bilateral economic and trade agreements with both Iraq and Iran; considering the considerable Iranian influence over the Iraqi government, these agreements will likely continue to strengthen Iran’s role in the economies of the entire Levant.

- At least 76 individuals were detained in Dar’a governorate in December 2018; notably, these detentions were for reasons other than military conscription, highlighting the challenges facing individuals in post-reconciled areas.

- The Government of Syria announced 30 new Russian economic projects throughout Syria. While these projects target the badly damaged Syrian industrial and agricultural sectors, there remains the persistent risk that the benefits of these projects will be captured by business class elites.

- Algeria forcibly deported at least 50 Syrian refugees to the Nigerien border in the Sahara desert; while the deportation is more indicative of Algeria’s policy toward refugees generally, there is the potential that Syrian refugees may be deported to Syria in the future.

U.S. Withdrawal from Syria

In Depth Analysis

On December 19, U.S. President Donald Trump announced in a tweet and a subsequent video on Twitter that ISIS had been defeated and the U.S. would consequently withdraw its forces from Syria. The announcement clearly came as a shock to U.S. allies and coalition partners, and officials within the Trump administration responsible for implementing the U.S. Syria policy. According to a Pentagon official speaking to CNN: “Obviously the DoD wasn’t consulted…or if we were, POTUS is disregarding Secretary of Defense [James] Mattis’ advice.” Since the announcement, the exact timetable for them to withdraw of U.S. military forces from its approximately 15 military bases in northeastern Syria remains unclear. Initially following the announcement, members of the administration were variously quoted as stating that the U.S. military would withdraw within 30-60 days; this timetable was validated by reports that U.S. diplomatic staff were evacuated from northeastern Syria on December 20. Yet following the public resignation of Defense Secretary Mattis and U.S. Envoy to the Global Coalition to Counter ISIS Brett McGurk, as well as considerable criticism from leading members of the Republican party, President Trump has extended the timeline for withdrawal to four months (120 days). The extension, as well as President Trump’s much-deserved reputation for erratic and impulsive behavior, has led some analysts to assess that the U.S. will not, in fact, withdraw from northeastern Syria; however, there are several reasons to believe that President Trump is fully committed to a Syria withdrawal.

While the specific drivers behind President Trump’s decision are impossible to identify, the decision to withdraw from Syria is likely grounded in two factors: Trump’s personal ideology and longer-term pragmatism with respect to the U.S.’ relationship with its long-standing ally, Turkey. President Trump has consistently maintained that he is an isolationist; in April 2018, President Trump made explicit statements indicating his preference for a U.S. withdrawal from Syria. Indeed, like President Obama, President Trump only maintained the U.S. presence in Syria by citing the fight against ISIS; while President Trump is not entirely correct that ISIS has been defeated in Syria, it is now relegated to controlling only several small villages and unpopulated deserts in eastern Syria. Yet, President Trump’s planned withdrawal from Syria were likely accelerated, or even catalyzed, by the elevated likelihood of a Turkish Armed Forces military intervention against the SDF in northern Ar-Raqqa. The fact that Turkey has grown increasingly distant from the U.S., and close to Russia, is in many ways a product of the U.S.’s continued support to the SDF. A Turkish intervention into northeastern Syria, without U.S. consent, would have irreparably damaged U.S.-Turkish relations, and possibly meant the de-facto end of the U.S.-Turkish alliance and Turkey’s role in NATO. In a sense, by withdrawing northeastern Syria, and likely ending its support to the SDF, the U.S. is reinforcing the Turkish-U.S. partnership in the Middle East. Evidence of this improving relationship is the December 18 announcement that the U.S. approved a $3.5 billion sale of U.S.-manufactured Patriot missile defense systems to Turkey, incidentally just one day before President Trump’s announcement to withdraw forces from Syria. Indeed, Turkey remains a major power in the Middle East – and in the context of very public criticism and Congressional condemnation of Saudi Arabia Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman – President Trump necessarily must secure his alliance with Turkey and prioritize Turkish over Kurdish interests.

The impact of the impending U.S. withdrawal has already been felt in two ways. The first major impact is that fears of an impending Turkish offensive following a potential U.S. withdrawal have drastically accelerated the negotiations between the SDF and the Government of Syria. The SDF and the Kurdish Self Administration likely view the presence of Government of Syria forces as the only long-term protection against a Turkish offensive. As of December 28, Government of Syria military forces have been deployed throughout SDF-held northeastern Syria, especially in the vicinity of Menbij and along the Syrian-Turkish border, where numerous analysts expected a Turkish offensive to occur. While the Government of Syria’s military presence will likely prevent a Turkish intervention for the time being, a broader and more comprehensive agreement between the Government of Syria and the Kurdish Self Administration will be necessary to mitigate a Turkish intervention in the future. The Government of Syria and the Kurdish Self Administration have been negotiating such an agreement for several months; however, without the presence of U.S. forces, the Kurdish Self Administration will likely be forced to negotiate on much more unfavorable terms, and the Government of Syria will likely be able to achieve a much more favorable agreement, to include a higher degree of integration of the Kurdish Self Administration into the Syrian state.

A second major impact of the U.S. withdrawal announcement is that it has brought the deep Kurdish-Arab tensions in northeastern Syria to the forefront of northeastern Syria’s political dynamics. Turkey has already called on armed opposition combatants originating from northeastern Syria to foment Arab dissent in their home communities. Additionally, and as noted in previous COAR Syria Updates, local sources report that Ahmed Al-Jarba, the former head of the Syrian Opposition Coalition and a prominent member of the Shammar tribe, has repeatedly visited Turkey, and is now reportedly involved in plans to form a new ‘tribal army,’ mobilizing Arab combatants currently aligned with the SDF. Turkey is not the only actor attempting to foment internal dissent within the SDF; the Government of Syria, through key intermediaries such as former member of parliament Nawwaf Al-Bashir, has also cultivated relationships with Arab tribal leaders in northeastern Syria, and is reportedly providing support to several of the numerous Arab anti-SDF ‘Popular Resistance’ groups that already exist in northeastern Syria. The U.S. withdrawal will compel Arab tribes throughout northeastern Syria to re-examine their relationship with the SDF and the Kurdish Self Administration, and many will likely choose to realign themselves with either the Government of Syria or Turkey, as both will be perceived as more valuable and longer-term patrons. This realignment will have the most drastic impact in the Arab majority areas that are currently controlled by the SDF, especially Menbij, Ar-Raqqa, and northern Deir-ez-Zor; however, it is worth noting that Arab tribal populations exist, and indeed form a majority, throughout much of northeastern Syria.

In the case of national-level negotiations and local Arab-Kurd tensions, several areas will likely be fully transferred to the Government of Syria or to Turkish-backed opposition groups in the near- to medium-term. This process of transferal will likely be coordinated by the Governments of Turkey and Russia: on December 29, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov stated that Turkey and Russia have already agreed to coordinate “on the ground…in connection with the troops withdrawal announced by the United States,” and on December 31, Turkey and Russia reportedly reached a yet to be released agreement regarding the fate of the city of Menbij.

International agreements will not necessarily supplant or preclude local Syrian negotiations; a broader agreement between the SDF and the Government of Syria will very likely be reached by which Kurdish Self Administration administrative structures will be reintegrated into corresponding Government of Syria structures. The Government of Syria has some experience in replacing and reincorporating administrative control, as evidenced by its ‘reconciliation’ strategy implemented throughout south and central Syria. Nonetheless, considering the generally amicable relationship between the Government of Syria and the Kurdish Self Administration, ‘reconciliation’ in northeastern Syria is likely to involve some degree of institutional transfer, as opposed to evacuation and replacement. Yet the eventual resumption of Government of Syria administrative control will have a dramatic impact on the humanitarian and development response in northeastern Syria. Many, if not the overwhelming majority, of humanitarian, development and stabilization actors active in northeastern Syria are not officially registered with the Government of Syria. These organizations will likely continue to see their physical access continue to shrink as areas are transferred or become inaccessible. While ‘remote partnerships’ may provide a short-term solution, Kurdish Self Administration reintegration will likely have a similar impact on cross-border humanitarian and development programming as has occurred in other reconciled areas.

Whole of Syria Review

1.

Gulf State Rapprochement

Damascus, Syria: Throughout the past week, multiple Arab countries affiliated with the Gulf Cooperation Council and the Arab League strongly indicated they intend to pursue rapprochement with the Government of Syria. On December 27, the United Arab Emirates announced the reopening of its embassy in Damascus, Syria; the UAE’s Foreign Ministry stated that the normalization of ties with Syria is aimed at “preventing the dangers of regional interference in Syrian affairs,” in a likely reference to the Iranian influence in Syria. Shortly after that, on December 28, Bahrain’s Foreign Ministry released a statement reiterating that its embassy in Syria continued to work throughout the conflict. On December 31, Kuwait’s Deputy Foreign Minister, Khaled Al-Jarallah, stated that Arab embassies reopening in Damascus should require approval from the Arab League, which spoke to Kuwait’s reluctance to normalize relations with and reopen its embassy in Syria. Notably, Sudanese President Omar Al-Bashir’s visit to Damascus on December 17 marked the first visit of an Arab president to Syria since 2011; the Syrian Head of the National Security, Ali Mamlouk and the Government of Egypt’s Head of Intelligence, Abbas Kamel, also held a meeting on December 23. Additionally, several statements made by Arab League officials and analysts alike have pointed out that members of the Arab league will consider readmitting Syria to the Arab league after having suspended the country in November 2011. Indeed, Arab League Secretary General, Ahmed Aboul Gheit, stated in April 2018 that the suspension of Syria had been a “hasty” decision.

Analysis: The United Arab Emirates’ reestablishment of its Damascus embassy highlights the general trend of Arab state rapprochement with Government of Syria, in particular the Arab Gulf States. Despite the fact that most Arab Gulf States states provided financial and military support to armed opposition groups, it is apparent that the Government of Syria will remain in control of Syria. Furthermore, the considerable economic opportunities as part of Syria’s reconstruction may have also caused Arab Gulf States to realign their Syria-specific foreign policy. Other countries that previously supported the armed opposition, such as Saudi Arabia and Qatar, are also likely to re-engage with the Government of Syria; however, Qatar will face additional challenges due to the perception of providing political support to the Muslim Brotherhood. For their part, the Government of Syria will likely welcome the formerly antagonistic Gulf States, both due to the legitimacy that rapprochement affords, as well as their expected participation in the economic rehabilitation and reconstruction of Syria, especially given the continued European and U.S. refusal to contribute to Syria’s reconstruction without political change.

2. Dar’a Detentions

Dar’a Governorate, Southern Syria: On January 1, the Dar’a Martyrs Documentation Office, an opposition-oriented monitoring organization, issued a document detailing the number of detentions that took place in Dar’a governorate in December 2018. Notably, the detentions listed excluded cases of detentions for military conscription. As per the document, the Government of Syria’s Criminal Security and Security Intelligence detained a total of 76 individuals, to include civilians and former opposition combatants who recently reconciled with the Government of Syria, as well as 23 women from Ash-Shajara subdistrict accused of affiliation with ISIS. It should be noted that this marked the largest number of women detained in one month since the reconciliation of southern Syria in June 2017.

Analysis: Continued detentions of civilians and reconciled individuals in southern Syria is representative of the security situation in reconciled areas in general. Reconciliation agreements, and post-reconciled areas, are inherently fragile; indeed, even one year after reconciliation, protection-related issues with respect to reconciled individuals may remain, regardless of previous agreements. The elevated numbers of detention may be due to the increased control exerted by the Government of Syria’s intelligence services. Similar incidents are likely to continue for the foreseeable future, as Government of Syria seeks to remove uncontrollable or untrusted elements of the local population, both in southern Syria and in other reconciled areas.

3. HTS Captures Daret Azza

Daret Azza, Western Aleppo Governorate, Northwestern Syria: On December 28, Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham accused the National Liberation Front-affiliated Noureddine Al-Zinki of killing five Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham members in Tilaada, in Daret Azza, western Aleppo governorate. Subsequently, on December 31, Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham and Noureddine Al-Zinki reached an agreement in order to prevent a wider conflict, which entailed the surrender of the individuals accused of killing the Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham members. Despite that agreement, on January 1 Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham launched an attack on Noureddine Al-Zinki positions in three different areas: Daret Azza, Tqad, and Khan Al-Asal, all in western Aleppo and eastern Idleb. As a result, Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham reportedly took control of Daret Azza and Jabal Sheikh Barakat, while reports indicate that clashes between Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham and Noureddine Al-Zinki continue. Local sources have also reported that Government of Turkey-supported National Army have now mobilized in Deir Samaan, 7km north of Daret Azza.

Analysis: Tensions and clashes between Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham and Noureddine Al-Zinki in western Aleppo governorate are not uncommon; however, it is noteworthy that Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham seized control over Daret Azza, as the city and the surrounding area has been under the control of Noureddine Al-Zinki since at least 2017 and the majority of Noureddine Al-Zenki’s combatants are from Daret Ezza and western Aleppo. The fact that Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham captured Daret Ezza drastically increases the likelihood of a broader conflict between Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham and the National Liberation Front in northwestern Syria; indeed, there are already indications that other National Liberation Front groups, such as Ahrar Al-Sham and Faylaq Al-Sham, are mobilizing in support of Noureddine Al-Zinki. Consequently, it is likely that the Government of Turkey will pressure Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham to withdraw from Daret Azza and surrender the area to National Liberation Front-affiliated groups; for its part, the Government of Turkey is likely not yet prepared to take decisive actions in the northwestern Syria disarmament zone, as its focus is presently on developments related to northeastern Syria. However, if the Government of Turkey fails to compel Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham to cede control of Daret Azza in the near term, it is likely that clashes and infighting between Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham and the National Liberation Front will erupt on numerous front lines in northwestern Syria.

4. Israeli Airstrikes

Al-Qutayfah, Rural Damascus Governorate, Syria: On December 25, Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) reportedly launched an airstrike on Al-Qutayfah, located in Rural Damascus; the aircraft reportedly travelled through Lebanese airspace before launching the attack. Government of Syria media outlets indicated that the attack targeted a weapon storage facility reportedly belonging to the Syrian Arab Army 4th Division, and resulted in the injury of three soldiers. The Government of Israel has yet to officially comment on the incident; however following the attack, the IDF stated that it had activated its aerial defenses in response to anti-aircraft missiles launched from Syria. On December 26, the Russian Foreign Ministry condemned the attack, and stated that Israeli warplanes threatened civilian flights at Beirut’s Rafic Al-Hariri International Airport, which was also reiterated by Lebanese authorities. The Lebanese Foreign Ministry also filed an objection to United Nations Security Council. Notably, the aforementioned attack is concurrent with ongoing IDF operations along Lebanon’s southern border, which aim to destroy alleged Hezbollah tunnels into northern Israel.

Analysis: Considering President Trump’s recent decision to withdraw from Syria, the Government of Israel’s policy of confronting Iranian influence in Syria and Lebanon will likely take greater priority and urgency. Israeli airstrikes have had a limited impact on the course of the Syria conflict for the past seven years; however, Israeli concerns regarding Iran are now heightened, and Israel may now consider taking more direct action against Iranian interests and Iranian proxy groups in Syria, especially Lebanese Hezbollah. As such, Lebanese-Israeli and Syrian-Israeli tensions are expected to increase; indeed, local Lebanese political tensions, and domestic Israeli challenges to Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu will likely to aggravate these tensions.

5. Unification of Druze Armed Groups in As-Sweida

As-Sweida city, As-Sweida Governorate, Southern Syria: On December 25, more than ten local Druze armed groups in As-Sweida governorate announced that they would integrate their forces under a unified command structure. The new unified Druze armed group will reportedly be led by the Sheyoukh Al-Karama; however, no name for the newly unified armed groups has yet been announced. As per their video statement, the groups articulated their opposition to ongoing conscription and detention campaigns carried out by Government of Syria security branches in As-Sweida governorate, and expressed their opposition to the continued recruitment of local Druze to take part in a “sectarian holocaust,” in reference to the Syrian conflict. The statement also included their refusal to surrender weapons and a rejection of the recent Government of Syria rhetoric, such as the labeling of Druze armed groups as terrorist and religious bigots. For the past three months, Government of Syria representatives have convened several meetings with local Druze armed groups, as well as Duze local notables and the Mashayekh Al-Akel, the primary Druze religious authority in Syria. The purpose of these meetings has reportedly been to compel the Druze to willingly submit to conscription; however, various Druze leaders and armed groups have consistently refused to oblige, citing their primary priority to protect their communities. As a result, the Government of Syria and Druze representatives have failed to reach a negotiated agreement.

Analysis: Given the high degree of social cohesion among the Druze community in As-Sweida, the Government of Syria’s attempts to broker unilateral agreements with local Druze factions, or even with individual Druze community leaders, is unlikely to succeed. The fact that local Druze armed groups continue to be closely aligned with community notables and the Druze religious leadership is expected to impede Government of Syria attempts to co-opt these groups. Despite fears of a potential conflict, it is unlikely that the Government of Syria will launch a major military or security campaign or crackdown in As-Sweida. Currently, the numerous Druze armed groups in As-Sweida are not part of an explicitly anti-Government of Syria movement; they are not revolutionary, nor aim to overthrow the Government of Syria. Instead, the Druze community is vehemently opposed to conscription of its male population to fight in other conflict theaters throughout Syria. Therefore, the Government of Syria will likely show a greater degree of flexibility with the Druze community, knowing that the approval of Druze leadership, especially the religious leadership, has been indispensable in maintaining control over As-Sweida. Until a formal agreement is reached with Druze leadership, confrontation and continued tensions are likely but will remain limited.

6. GoS Deployment in Eastern Syria

Eastern Deir-ez-Zor Governorate, Syria: On December 21, the Government of Syria deployed the 5th Division to eastern Deir-ez-Zor in order to combat the remaining ISIS forces in the eastern Syrian desert. The 5th Division largely consists of reconciled combatants from Dar’a and is led by Ahmad Oudeh. Russia initially established the 5th Division, continues to provide it considerable support, and this most recent deployment to Deir-ez-Zor was reportedly urgently requested by Russian representatives. Meanwhile, clashes between SDF and ISIS continue to take place in lower Baguz village, in eastern Deir-ez-Zor governorate, in the vicinity of 5th Division positions.

Analysis: In light of the U.S. decision to withdraw forces, the Government of Syria likely sees an opportunity to promote itself as the primary force combating ISIS, especially considering the fact that threats of a Turkish intervention will likely compel the SDF to shift its priorities away from combating ISIS. Indeed, with Government of Syria forces jointly deployed with the SDF in Menbij, it is possible that the Government of Syria may now coordinate with the SDF on multiple fronts, to include eastern Syria. However, it is also likely that the Government of Syria, under the direction of Russia, is deploying forces to Deir-ez-Zor in preparation for the SDF handing control of northern Deir-ez-Zor to the Government of Syria, as the SDF and the Government of Syria are now involved in high-level negotiations with respect to northeastern Syria.

7. Syrian Refugees Return from Lebanon

Beirut, Lebanon: On December 24, more than 1,000 Syrian refugees reportedly returned to Syria from Lebanon. Lebanese media sources stated that their return was facilitated by Lebanese Internal Security Forces throughout Lebanon, to include in Saida, Shebaa, Tyre (Sour), Beqaa, Beirut, Nabatiyah, Mount Lebanon, Akkar and Tripoli. According to Lebanese and Syrian media, the majority of the returnees are originally from Madamiyet Elsham, in Rural Damascus governorate; among them are reportedly four former Syrian Arab Army generals who defected, and whose return was reportedly facilitated by the 4th Division of the Syrian Arab Army. Furthermore, a member of the Madamiyet Elsham reconciliation committee indicated that only 800 of those who returned have been approved by both the Governments of Lebanon and Syria; he also pointed out the this will be the last group of refugees to return to Madamiyet Elsham, as the rest have either refused to return or have been denied security approvals by the Government of Syria.

Analysis: The fate of Syrian refugees returning to Syria from Lebanon remains extremely difficult to monitor, especially considering the fact that there are no formal or specific agreements between the Governments of Syria and Lebanon governing returns procedures. This has been compounded by the fact that Lebanon has not established a government since the May 2018 elections, and that the Lebanese caretaker government is incapable of forming a unified set of policies or agreements. As a result, the Lebanese security authorities have been given sizeable influence and authority over the process of Syrian refugee returns. The case of refugees returning from Lebanon without Government of Syria approval, and accompanied status reconciliation, is especially concerning due to protection-related issues. The general ad-hoc process of refugee returns from Lebanon raises additional questions and concerns with respect to coercion.

8. Syria-Russian Economic Agreement

Damascus, Syria: On December 26, the Head of Government of Syria National Planning Committee, Imad Sabouni, stated that 30 Russian economic projects will be implemented throughout in coming two years in Syria. As per his statement, most of the projects involve Syria’s industrial sector; prominent examples include the rehabilitation of a tire company in Hama and the construction of a new cement factory in Musallamiyeh, Aleppo governorate. Other projects include supporting water networks that link Tishreen Dam to Lattakia governorate, as well as projects in the health sector, transportation networks, and the rehabilitation of wheat silos. This agreement is the product of several meetings between Syrian and Russian joint committees that aim to discuss further economic cooperation between both countries.

Analysis: Economic cooperation between the Governments of Russia and Syria are expected to increase, as Russia continues to invest in industrial and agricultural development, as well as natural resource production. However it is worth noting that throughout recent Syrian history, foreign investments in the Syrian economy have generally been converted into either immediate service provision projects, or short-term projects aimed at quick profits for the Syrian business class, at the expense of long-term investment that provides industrial or agricultural development. Considering that local industry and agriculture are the foundation of the Syrian national economy, ensuring that development and rehabilitation projects resolve unemployment issues and generate income for those must in need is likely a major Russian priority. However, it is important to note that most reconstruction, rehabilitation, and economic development projects are expected to further empower the existing Syrian regime-linked business class in Syria, possibly at the expense of the Syrian population or the long-term health of the Syrian economy.

9. GoS-Iraqi-Iranian Economic Cooperation

Baghdad, Iraq: On December 18, Iraqi Transport Minister Abdullah Luaibi convened a meeting with the Syrian Ambassador to Iraq, Satam Jadaan al-Dandah, during which they discussed potential cooperation in land and air transportation infrastructure. Both officials reportedly emphasized the necessity of enhancing trade and transport through the Abu Kamal/Al-Qaim border crossing; Luaibi also stated that Iraq will seek to revitalize Iraqi airline transport to Syrian airports. Relatedly, on December 29, members of the joint Syrian-Iranian Ministerial Economic Committee held a meeting in Tehran, Iran to discuss establishing longer-term economic cooperation between the two countries. This follows a statement made on December 20 by Iranian Deputy Minister of Roads and Urban Development, Ameer Amini, which described the Government of Iran’s intention to facilitate cooperation between the Iranian private sector and Government of Syria, with the Iranian Central Bank acting as the primary platform. As per his statement, a joint Syrian-Iranian MoU is in development, which aims to enhance Iranian investment in Syria. Amini also indicated that the Iranian private sector, especially the Khatem Al-Anbiyaa company, is currently investing in Syrian phosphate and reconstruction materials such as cement factories. Of note, the Khatem Al-Anbiyaa company was established during Iran-Iraq war of 1980-1988 to help in the reconstruction of Iran; it is now a leading company in the Iranian development and industrial sector, and is directly linked to the Iranian Revolutionary Guard.

Analysis: Syrian, Iranian, and Iraqi economic cooperation is highly noteworthy, especially considering the fact that Iran holds considerable influence over Iraqi politics, and has been deeply involved in the Syrian conflict and war economy. By facilitating economic agreements between Iraq and Syria, as well as forging new agreements between Syria and Iran, Iran will be able to ensure the development of long-term economic linkages throughout much of the Levant. Five transit routes link Iran, Iraq, Syria and Lebanon; the most important crossing points extend from Iran to Baghdad and through to the Al-Qaim/Abukamal and the Al-Tanf border crossings with Syria. While the agreements between Syria, Iraq, and Iran are currently bilateral in nature, it is likely that they will eventually become multilateral, mutually beneficial economic agreements, especially related to transportation infrastructure, as well as resource extraction, processing, and refinement, which will likely pave the way for increased Iranian influence on economic activity in the Levant as a whole.

10. Algeria Deportations

Algiers, Algeria: On December 26, media sources indicated that the Government of Algeria deported a total of 50 Syrian refugees to its border with Niger, after detaining them for 85 days under charges of illegal entry into the country. Notably, the same sources have reported that the Government of Algeria is exploring the possibility of deporting Syrian refugees directly back to Syria. This came after Algeria had reportedly ceased the deportation of refugees and migrants to the Sahara desert in July 2018, after wide condemnation by media, the UN International Organization for Migration, and Human Rights Watch.

Analysis: Throughout 2018, Government of Algeria has reportedly deported thousands of sub-Saharan and Arab migrants and refugees, of various nationalities, to its borders with Niger and Mali in the Sahara desert. Human Rights Watch also reported on numerous cases of police brutality, detention, and harassment of refugees in Algeria. The deportation of Syrian refugees from Algeria is likely not a policy specifically targeting Syrians, but rather a manifestation of Algeria’s general policy toward migrants and refugees. However, as in all cases of forcible deportations, Syrian refugees forcibly returned to Syria naturally face significant protection concerns, as they likely have not had sufficient opportunity to formally reconcile their status with the Government of Syria.

The Wartime and Post-Conflict Syria project (WPCS) is funded by the European Union and implemented through a partnership between the European University Institute (Middle East Directions Programme) and the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR). WPCS will provide operational and strategic analysis to policymakers and programmers concerning prospects, challenges, trends, and policy options with respect to a conflict and post-conflict Syria. WPCS also aims to stimulate new approaches and policy responses to the Syrian conflict through a regular dialogue between researchers, policymakers and donors, and implementers, as well as to build a new network of Syrian researchers that will contribute to research informing international policy and practice related to their country.

The content compiled and presented by COAR is by no means exhaustive and does not reflect COAR’s formal position, political or otherwise, on the aforementioned topics. The information, assessments, and analysis provided by COAR are only to inform humanitarian and development programs and policy. While this publication was produced with the financial support of the European Union, its contents are the sole responsibility of COAR Global LTD, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.