Tribal Tribulations

Tribal Mapping and State Actor Influence in Northeastern Syria

06 May, 2019

Executive Summary

Tribes, specifically Sunni Arab tribes, are an increasingly prominent and influential political force in northeastern Syria. The relative power of tribes is in many ways a function of demographics; despite popular misconceptions, Arab tribesmen remain the majority of the population in most major communities in Kurdish Self Administration-controlled northeastern Syria, and an important plurality or potent minority in many nominally Kurdish communities. States party to the Syrian conflict, primarily the Governments of Syria, Turkey, and Iran, are aware of this dynamic and have been courting tribes for years, in many ways as part of a formal foreign policy instrument; this outreach has only increased in scope and scale following the military defeat of ISIS. Yet tribes are also often misunderstood, particularly in the west: while Arab tribes are indeed important socio-political entities, they are not monolithic; thus, it is difficult in most cases to determine a single tribe’s ‘affiliation’ with a specific political or state actor due to diffuse structures and decision-making. At present, states conducting tribal outreach do so through forging relationships with individual tribal leaders as a means of securing local influence. While the term ‘tribal leader’ is open to debate, in practice states have identified popular or influential individuals capable of mobilizing significant support within a kinship-based solidarity network.

By means of mapping Arab tribes in northeastern Syria and overlaying reported political affiliation, it becomes clear exactly which, and where, states are building and leveraging influence with Arab tribes in northeastern Syria as a means of achieving geopolitical objectives. This research is especially interesting and predictive when taken in the context of current socio-political realities, specifically that the Kurdish Self Administration is unlikely to exist in its present form indefinitely. When the Kurdish Self Administration eventually concedes territory – either through a broad arrangement with the Government of Syria or as a result of a Turkish-led military intervention – the precise locations of state-tribal influence not only indicates political and geographic areas of interests, but also hints at potential fissures and future areas of likely violence in northeastern Syria.

Data collection supporting the conclusions presented in this paper occurred over a period of two months, and relied on key informant interviews throughout northeastern Syria. In addition to mapping the locations of specific tribes in northeastern Syria, field researchers also examined the socio-political structures of Arab tribes in northeastern Syria, as well as identifying those essential qualities necessary for tribal leadership. A series of tribal maps, detailing the geographic distribution of the most prominent twenty-five tribes in northeastern Syria and Menbij, and which regional actors have courted these tribes, are also presented alongside methodological explanations concerning how data contained in these maps was compiled. Please note that the emphasis of this research is on socio-political relationships, geopolitical interests, and foreign interventions in Syria, rather than a study of tribal demographics or tribal political ‘affiliations’. A set of findings and recommendations for institutional donors and INGOs is also presented in this paper.

Tribal Outreach

Influence Building as a Destabilizing Force

Over the past year, it is increasingly clear that the Governments of Syria, Turkey, and Iran have embarked on a policy of ‘tribal’ outreach in northeastern Syria. Ultimately, the purpose of this policy is to secure relationships with northeastern Syria’s Arab tribesmen to create spheres of political influence within territory presently controlled by the Kurdish Self Administration and the SDF, to which the Governments of Syria, Turkey, and Iran are all opposed, albeit each for specific reasons.

The Governments of Syria, Turkey, and Iran have different mechanisms for tribal outreach and relationship building with northeastern Syria’s tribes. In general, the Government of Syria has used its pre-existing personality-based relationships with tribal leaders and representatives[footnote]Perhaps the most notable tribal conference led by the Government of Syria was the Ithriya conference in January 2019, which thousands of prominent Syrian tribesmen and tribal leaders attended.[/footnote], whereas the Government of Turkey has leveraged relationships with Arab tribal combatants and leaders from northeastern Syria that subsequently relocated to northern Aleppo and are now a major component of the Turkish-supported National Army initiative.[footnote]Turkey has also held several tribal conferences, most notably in Istanbul and Urfa.[/footnote] For its part, Iran often builds relationships with Syrian tribes by funding militias that have a heavy tribal component, or by leveraging the cross-border socio-political linkages shared between Syrian tribes and the Iraqi tribes that form an important component of the Iraqi Hashid Shaabi.[footnote]See for example the Bekkara tribe, the Al-Dleim tribe, or the Al-E’beid tribe, which are covered in detail in the annex of this paper.[/footnote] This strategy of tribal outreach and influence is fundamentally predicated upon the identification of real or ‘created’ tribal leaders, and then the mobilization of financial and military support with the intention of leveraging patronage for local influence. Tribes themselves are selected based on geographic areas of demographic prominence.

It is important to note that the purpose of building relationships with Syrian tribal leaders and tribes extends beyond the objective of securing local support; Arab tribes are also instrumentalized as a means of undermining political foes. For example, tribal leaders with local support can call upon fellow tribesmen to foment domestic protest movements[footnote]Perhaps the most dramatic example is the tribal protest movement which was formed in Ar-Raqqa following the November 2018 assassination of the popular sheikh of the Afadleh tribe, Bashir Al-Huweidi. Al-Huweidi’s assassination led to numerous tribes in Ar-Raqqa to declare a general strike, and to call on fellow tribesmen to avoid working with the Kurdish Self Administration. More information can be found throughout the annex to this paper, particularly the section on the Afadleh tribe.[/footnote], form local armed groups[footnote]Examples would include the Lions of Popular Resistance, the Popular Resistance of Ar-Raqqa, or the Popular Resistance of Eastern Syria, all of which are anti-SDF armed groups that are decidedly comprised of Arab tribesmen.[/footnote], or create new political parties and blocs. By cultivating relationships with tribal leaders, regional states party to the Syrian conflict are essentially building local constituencies and intermediaries willing to support their respective strategic policies. Thus, state outreach to Arab tribes in northeastern Syria should not necessarily be viewed as a purely stabilizing or destabilizing force; it should instead be viewed as a form of community outreach. For those who understand its merits, tribal outreach has become an essential component of foreign policy in tribally prominent regions, and the cultivation of tribal leadership figures should be viewed through precisely this lens: a clear indication that a neighboring state has a specific strategic interest in the particular geographic area where tribal allies are most prominent. This, in turn, helps to illustrate, map, and forecast not just interests and alliances, but also potential areas of friction and groups most likely to be instrumentalized as local proxies.

What is a Tribe?

Despite the critical political importance of tribalism throughout Syria, the ‘tribe’ remains a concept that poorly understood.[footnote]Indeed, understandings of the Middle Eastern tribe often come from orientalist or colonial frameworks. Under these frameworks, the tribe is either considered to be a far more important and unified entity than it actually is, or its importance is dismissed altogether.[/footnote] Definitions and understandings of a ‘tribe’ vary, especially in the Middle East where the concept has been shaped by both historical practices and more recent social, economic, and political changes associated with modern state formation. Indeed, academics and practitioners regularly debate the importance of the ‘tribe’ in the modern Middle East, and entire books have been written on the topic of tribalism and tribal boundaries.[footnote]Much of this section is drawn from Tribes and State Formation in the Middle East, a collection edited by Phillip Khoury and Joseph Kostiner; The Ottoman Background of the Modern Middle East by Albert Hourani, and The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries by Andreas Wimmer were also consulted.[/footnote] However, most practitioners do agree on two key characteristics of the tribe in the Middle East: the tribe is an socio-political identity and solidarity network; and a tribe is informed by shared kinship networks based on common paternal descent.[footnote]The degree to which there are true biological relationships between tribal members is often irrelevant – what is more important is the idea of a common ancestor that tribal members claim descent from. Indeed, it is not uncommon for tribal ‘founders’ to be almost mythical figures; it is the idea of a common ancestor, and the perception of kinship ties, that is perhaps more important than actual biological reality.[/footnote] Mohammad Jamal Baroud, a prominent Arab social scientist, refers to the tribe using the concept of muhit hayawi ijtima’i, which is best translated as a person’s ‘essential social environment.[footnote]Please see: A Contemporary History of the Syrian Jazeerah: Challenges of Urban Transition for Nomadic Communities, published in 2013.[/footnote] Fundamentally, tribal affiliation is an immutable characteristic; i.e. a member of the Jabour tribe cannot convert and become a member of another tribe, and that status will also inform behavior patterns within the broader socio-political environment.[footnote]To say tribal affiliation is ‘immutable’ is perhaps not entirely true. Individuals can theoretically be adopted into tribes, although this is extremely rare and often takes place with young orphans. Additionally, tribes can and have merged, though often in the distant past. Tribes can also break away from parent tribes, and several of Syria’s most prominent tribes are offshoots of larger tribes. However, this does not change the fact that there is an essential, unchanging, common ancestor-based component of tribal identity. For example, in Syria the Al-Bursan tribe is an offshoot of the Al-Weldeh tribe; this took place when a prominent Sheikh of the Al-Weldeh tribe, along with his kin, broke away from the Al-Weldeh in the 1940’s and became the ‘founder’ of the Bursan. However, while a prominent tribal leader can potentially form a new tribe, he cannot become a member of another tribe; he is either a member of the tribe of his father, or the founder of a new lineage.[/footnote]

While the tribe is perhaps a person’s ‘essential social environment’, it is worth noting that the tribe, at least in Syria, is not a cohesive socio-political unit. Prior to the implementation of the Ottoman Tanzimat reforms, the tribe was (in many cases) more politically unified and led by a single, often hereditary, Sheikh. In modern Syria, the socio-political significance of tribal identity varies wildly, differs by individual and community, and in many cases is informed by socio-economic and geographic backgrounds. Anecdotally, individuals who have migrated to urban centers, work as urban professionals, or who no longer reside within kinship or tribally-based communities are less influenced by their tribal identity. However, this does not mean that a northeastern Syrian tribesman who is now an engineer in Damascus does not feel strongly about his tribal identity; conversely, it would be wrong to assume that a farmer in Raqqa’s decision-making is solely informed by tribal relationships. For many, tribal affiliation is just one of a plurality of social identities, to include for example ‘Muslim,’ ‘Syrian,’ ‘Arab,’ or ‘Raqqawi.’

That said, tribes throughout northeastern Syria remain an important component of social identity; tribal affiliation informs the composition of many communities, and tribal leadership figures often perform important governance functions such as dispute mediation, economic welfare and patronage, and the provision of basic safety and security. Indeed, while in most cases the tribe has ceased to be a ‘unified’ socio-political entity, it nonetheless remains a strong social identity that can and is politicized when formal governance structures recede. In the context of the Syrian conflict, shared ‘tribal’ identity is often a critical component of armed group membership, the formation of political blocs, and the basis of popular mobilization. Consequently, ‘tribal’ leaders are often viewed as powerful political brokers, though as noted the ‘tribe’ as a socio-political construct is far less relevant and more fragmented today than in the past.

What is a ‘Tribal Leader’

It is important to examine the profiles of individuals that are considered to be tribal leaders, as these individuals are key nodes within the broader policy/strategy of leveraging tribes as a means of achieving local political influence. Here it must be noted that Syrian tribes rarely (if ever) have an undisputed single leadership; rather, each tribe often has multiple and sometimes competing leadership figures. Additionally, leadership is more diffuse in the case of extremely large tribes, such as the Jabour, with constituent membership spread across throughout northeastern Syria and numbering in the hundreds of thousands, and is more concentrated in smaller tribes such as the Jiss, which are located in the vicinity of Tel Abiad and number in the low thousands. Naturally, a larger tribe will have numerous leaders, different leadership figures will hold multiple socio-political and economic relationships, and leaders may be engaged in some form of competition with one another. This leads some analysts to contend that – in the case of large tribes with diffuse leadership – the tribe is politically insignificant. Paradoxically, larger tribes with numerous tribal leaders, each pursuing different political strategies, actually can make the tribe more relevant and potent politically, especially in that this strategy ensures that some component of the tribe is always aligned with the ‘winning’ actor.

Ultimately, there are four essential components that define tribal leadership in present-day northeastern Syria: family, funding, friendships, and fighters. Tribal leaders must have some or all of these components to remain influential and thereby gather popular support amongst fellow tribesmen; tribal leaders that lose some or all of these components will consequently diminish in relevance and prominence.

Family

Tribal leaders must, obviously, be members of the tribe. Ideally, leaders hail from the more prominent families within that tribe that have traditionally and historically held leadership positions. As the tribe is fundamentally based on the idea of a shared kinship, the ability to call upon hereditary history to justify leadership claims is an important component of a tribal leader’s legitimacy. Of course this is not always the case; a tribal leader whose father was an effective leader will not retain a following if he is ineffective or lacking in other key leadership qualities. However, an overwhelmingly large number of northeastern Syria’s tribal leaders claim a familial history of leadership within the tribe. It is indeed rare to find a leader without a hereditary pedigree.[footnote]Local researchers could not identify a single person they considered to be a tribal leader in that did not come from the ‘leadership families’ of northeastern Syria.[/footnote]

Funding

Tribal leaders in northeastern Syria must secure economic resources, and subsequently distribute those resources to tribesmen as part of securing patronage. Indeed, this is perhaps one of the primary reasons that tribal identity has survived as an institution; the ability to draw upon fellow tribesmen or tribal leaders for economic support is an important part of maintaining tribal affiliation as a component of one’s identity. This could account for the geographic and economic linkages to tribal identity as a part of social identity; the aforementioned tribesman-engineer living in Damascus no longer relies as heavily on tribal leaders for economic security. Therefore, access to cash, jobs, or land to reliably (and ideally, equitably) distribute to fellow tribesmen is an essential component of a tribal leader’s legitimacy.[footnote]Or note, one local researcher noted that the most important of these economic resources is land. Tribal leaders often personally own large tracts of land (to include agricultural land, pastoral-use land, or urban properties), which they allow tribesmen to use for free or for only nominal rents. It is not uncommon for tribal leaders to allow tribesmen to farm agricultural land in return for a percentage of the total crop yield, in a system that is functionally indistinct from the Ottoman-era.[/footnote]

Tribal leaders attending a Turkish held meeting in Urfa in December 2018. Photo courtesy of Daily Sabah.

Friendships

Successful tribal leaders in northeastern Syria must draw upon a network of allies, both inside and outside the tribe, to facilitate dispute mediation, external representation, and guarantee funding and internal patronage. Tribal leaders first and foremost are mediators of local disputes within the tribe: relationships with prominent tribal members is essential to building consensus and maintaining legitimacy.[footnote]Researchers note that consensus building is extremely important when mediating internal tribal disputes; tribal leaders cannot be seen to favor one family or individual over another, and must ensure that disputing parties are treated equally in order to attempt to maintain tribal cohesion. This often leads to dispute resolutions which do not actually satisfy either party; however, both parties being mutually dissatisfied is usually considered to be a better result than only one being satisfied.[/footnote] Tribal leaders must also hold relationships with other tribal leaders, both as a critical component of dispute and conflict mitigation, as well as developing broad-based political and social alliances. Tribal leaders must also hold relationships with non-tribal actors, such as with officials within their respective state, neighboring states, and local governance bodies; tribal leaders often derive considerable legitimacy from these relationships, as they are often a means of securing greater funding and patronage opportunities. Indeed, these extra-tribal relationships are often a critical component of why one tribal leader gains prominence over a competitor within the same tribe. The Syrian Government, the Kurdish Self Administration, and regional governments often select to engage and empower tribal leaders perceived as most relevant locally; thus, perceived internal support leads to additional external support, which in turn facilitates greater internal support and prominence.

Fighters

Tribal leaders in northeastern Syria must be able to call upon a large number of supporters to help pursue local and regional political objectives. Yet supporters are not necessarily armed combatants to be armed combatants, but can also be protestors or voters in local elections. Ultimately however, a tribal leader must be able to gather large numbers of fellow tribesmen behind a common cause or in support of a more powerful actor whose interests align with those of the tribe. The capacity to rally supporters not only influences the perception of a tribal leader’s potency vis-a-vis states -both internal and external- but also influences internal legitimacy vis-a-vis. The ability to mobilize supporters will heavily influence which tribal leader local or national actors support, and yet the associated patronage allows a broader powerbase, more local support, and greater legitimacy. Thus, local support and mobilization is both a cause and a result of funding and friendships.

Tribal Mapping and Geographies of Influence

As noted, regional actors and the Government of Syria are engaged in a strategy of building influence in northeastern Syria, primarily as a means of opposing or destabilizing the Kurdish Self Administration; tribal outreach, through engagement with tribal leaders, is a key component of that strategy. The degree to which this strategy has been successful is debatable, as it remains difficult to identify whether popular discontent is the product of poor governance on the part of the Self Administration, or the product of a calculated ‘tribal’ policy by the Kurdish Self Administration’s adversaries. Furthermore, the degree to which a tribe can be ‘aligned’ with a regional actor also remains unclear, especially considering the fact that most of northeastern Syria’s tribes are not monoliths and many boast fragmented leadership. Nonetheless, by overlaying patterns of tribal outreach or engagement upon rough areas of tribal influence, we can begin to understand the specific geographic interests and objectives of these external actors in the context of northeastern Syria. Mapping the potential political faultlines and external interests within northeastern Syria is especially relevant were we to assume that the Kurdish Self Administration is unlikely to exist in its current form indefinitely. Indeed, most analysis on the trajectory of the Kurdish Self Administration identifies a high likelihood that its territory will eventually be administered by either the Government of Syria or Turkish-backed groups. Therefore, by understanding where regional actors are building influence, we can gain some insight into the eventual geographic contours of control in northeastern Syria; we can also see where multiple regional actors are simultaneously building influence, which may contribute to longer term instability.

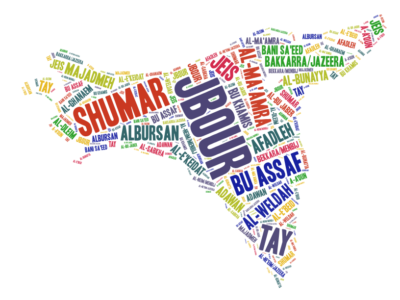

Methodology: Tribal Mapping

To map the distribution of northeastern Syria’s tribes is difficult under any context, all the more so in the midst of a violent conflict; furthermore, COAR lacks the resources to deploy survey and polling teams to work for months to collect tribal demographic data at the field level. In the interest of simplicity and speed – and in recognition of the fact that the objective is to identify regional objectives not local demography – COAR local researchers, from different ethnic backgrounds and based in northeastern Syria, collected tribal distribution data over the course of two months. Researchers identified the three most politically influential Arab tribes in each community (as per the UN gazetteer) within Ar-Raqqa, Deir-Ez-Zor, and Al-Hasakeh governorates, as well as SDF-controlled Menbij district in Aleppo governorate. COAR erred on the side of overrepresentation and in the case of discrepancies, both responses were noted. Ultimately, twenty-five different tribes were listed as influential across all of northeastern Syria’s communities. It is of course worth noting that there are hundreds of tribes and sub-branches of tribes throughout northeastern Syria; therefore, the findings presented below should not be taken as an accurate representation of tribal demographic distribution in northeastern Syria. Rather, findings should provide a snapshot with respect to the location of northeastern Syria’s most politically significant tribes at the community level.[footnote]Some tribes were also to some extent divided geographically. For example, the Bakkara and Al-Neim branches in Menbij and Jezeera were considered separately.[/footnote] Findings were subsequently cross-referenced with existing social media information, previous tribal mapping projects in northeastern Syria, and findings of analysts focused on northeastern Syria.[footnote]For example, see Fabreche Balanche’s work on Tel Abiad; Andrew Tabler’s work on Ar-Raqqa; Akil Hassan’s work on northeastern Syria; or Khedder Khaddour and Kevin Mazur’s work on eastern Syria tribal dynamics.[/footnote]

Note that each community assessed is represented by one point on the map above. Points with only a single color are communities with only one tribe considered to be the most influential. Points divided into two, three, or four colors show communities with multiple tribes listed as influential.

Methodology: Geographies of Influence

Researchers subsequently were asked to collect data with respect to the various national and regional actors conducting outreach to those representing or leading the most twenty-five influential tribes in northeastern. As noted, the most prominent external actors currently conducting outreach to northeastern Syria’s tribal leadership figures are the Governments of Iran, Russian and Syria; thus, individual tribes were coded based on a determination as to whether key tribal leadership regularly interacted with or received direct support from the Governments of Syria, Turkey, Iran or their representatives. Data from researchers was subsequently triangulated using methods similar to those listed above, and cross-referenced with COAR’s past research and the work of other researchers and academics.

It must be emphasized that this map is not attempting to display the political ‘affiliation’ of northeastern Syria’s tribes. As noted repeatedly, tribes are highly complex socio-political entities, some numbering in the hundreds of thousands, and many with multiple leadership figures. Thus, this map is not intended to represent tribal affiliation but rather state engagement with corresponding areas of tribal socio-political prominence. Essentially, this map shows where regional actors are attempting to build influence, and not necessarily what political direction tribes are taking.[footnote]Researchers were also given the SDF/Kurdish Self Administration as a tribal leader engagement category; however, 20 of the assessed tribes have tribal leaders regularly engaging with or taking support from the SDF or the Kurdish Self Administration. This is natural as the Kurdish Self Administration is the controlling governance actor in the areas where these tribal communities live. This phenomenon is important, as should the SDF or the Kurdish Self Administration cease to exist in its current format, many of the tribal groups and leaders that are currently nominally affiliated with the SDF will likely fall back on other regional power backers. Of note, only one tribe, the Bunayya, were exclusively engaging with the SDF. Researchers were additionally given ‘Gulf States’ as a tribal leader engagement category; however, there were no significant trends reported, as Gulf State interaction with tribal leaders was largely in support of the SDF as part of the U.S. coalition.[/footnote] That being said: many tribes are certainly openly aligning with different national and regional actors, and some are doing some as fairly unified socio-political entities. Ultimately, the way in which tribal engagement was categorized was a perceptional ‘gut check’, albeit one based on considerable research and guided by local sources; specific details on each tribe, including information on how the tribe was categorized, is included in Annex 1.

Findings/Conclusions

This map shows communities as points, with tribes recategorized based on which regional actors have engaged prominent tribal leaders. Tribes and tribal leaders are either categorized as: exclusively engaging with Turkey; exclusively engaging with the Government of Syria; engaging with both Turkey and the Government of Syria; or engaging with both the Government of Syria and Iran. Note that a circle colored half ‘Turkey’ and half ‘Government of Syria’ indicates that there are two prominent tribes in that community, one which is engaging exclusively with the Government of Turkey, and one which is engaging exclusively with the Government of Syria. There were no tribes whose leadership figures were exclusively engaging with Iran, there were no tribes with leadership figures that were engaging with both Turkey and Iran, and there were no tribes with leadership figures engaging with all three actors

This map displays the same data as above, but instead as an aggregate heat map. It is an attempt to give a more clear picture of the ‘contours’ of influence in northeastern Syria.

As seen on the map above, there are several points are of immediate interest. Regional actors are already defining zones of influence in northeastern Syria, and clearly view the tribe as a key component of that influence strategy. Considering the precarious political position of the SDF and likelihood that Kurdish Self Administration territory will be handed over to regional actors or be politically divided, it is worth examining the geographic contours where these actors are attempting to build influence. These contours may come to represent informal zones of influence or political division of NES, as well as potential flashpoints of tensions between various proxy groups. Below is a list of key findings:

The Government of Turkey is clearly building influence in the immediate Syrian border region, as well as Menbij; Turkey areas of influence line up closely to the dimensions of a proposed Turkish ‘safe zone’ in northeastern Syria. Indeed, the Government of Turkey is exclusively engaging with tribal leaders in the Jiss and Adwan tribes, the most influential tribes in both Ras El-Ain and Tell Abiad.[footnote]Both tribes are interesting cases, and are explored in depth in Annex 1.[/footnote] In fact, Turkey is building influence with tribes throughout northeastern Syria, although this is most notable in northeastern Syria’s major communities. Considering Turkey’s overtly hostile stance to the Kurdish Self Administration, Turkish influence-building with Arab tribes should be considered to be not only based on projected political outcomes but also with the intention to use these relationships to destabilize the Kurdish Self Administration.

The Government of Iran is clearly interested in building influence in northeastern Syria’s commercial corridors. This includes the Abukamal and Fishkabour border crossings, as well as Deir-ez-Zor city. This pattern is logical, especially given Iran’s well-documented interest in building commercial connections between Tehran and Syria, as well as its interests in Syria’s natural resources (such as Deir-ez-Zor’s oil fields). Indeed, Iran has already taken a major role in the port of Lattakia, and has also become a major stakeholder in Syrian Railways, and there are reportedly plans to expand the Syrian railway network to eastern Syria. Iran’s influence with northeastern Syria’s tribes has also caused some degree of internal friction within many tribes; for example, the Bakkara, one of northeastern Syria’s largest tribes, has already reportedly experienced some internal division between pro- and anti-Iranian camps.[footnote]For more information please see Annex 1.[/footnote]

The Government of Syria is attempting to build influence with northeastern Syria’s tribes throughout nearly all of northeastern Syria. It should not be surprising that the Government of Syria’s tribal approach is as widespread as it is; the Government of Syria has maintained relationships with Syria’s tribal community for decades, and has existing tribal leaders with which it prefers to work. Additionally, and as explored in Annex 1, many tribal leaders in northeastern Syria are also current or former members of Syrian Parliament, or are otherwise important local political officials and Baath party members. This pattern of influence whereby informal power brokers take on formal roles also fits within the Government of Syria’s overarching strategy.[footnote]This dynamic is also seen in the Syrian business community, where prominent businessmen become parliament members in order to draw them closer to the state.[/footnote]

There are several major potential points of conflict, identified as locations at which regional actors are simultaneously building multiple influence groups; this approach could lead to internal tribal conflict, armed group confrontation, and local instability. As seen on the holistic map above, this dynamic is especially prevalent in Ar-Raqqa city, Deir-ez-Zor city, and central Al-Hasakeh. Essentially, the fact that tribal leaders from tribal groups in these areas have been engaging with, and drawing support from, multiple regional actors is an indication that multiple separate patronage structures and influence bases exist. Indeed, Deir-ez-Zor city and Ar-Raqqa especially have already witnessed considerable internal tensions between tribal actors.

It is worth noting most tribes are also engaging with the SDF and the Kurdish Self Administration; however, this is due to the Kurdish Self Administration’s current role as governing body in northeastern Syria, and not due to any inherent loyalty (at least in most cases). As noted, tribes are inherently decentralized; however, they are also inherently self-interested. Tribes are also notoriously reactive to prevailing power dynamics; they do not often drive political or military dynamics, but they certainly react to the impact of these dynamics. So long as the longevity of the SDF and the Kurdish Self Administration is in question – and their longevity will always be in question due to the potential U.S. withdrawal and threats of Turkish intervention – many Arab tribal leaders will continue to pursue independent policies, and regional actors will use tribal leaders to build a power base with which to destabilize the Kurdish Self Administration, or to solidify their own eventual control over an area.

Recommendations

- The major national and regional parties to the conflict obviously consider tribal influence-building to be a fundamental component of their strategy in northeastern Syria, yet humanitarian and development actors more often than not do not take the same approach. They should. INGOs working throughout northeastern Syria must identify which tribes are locally relevant in communities in which they are working, and should seek to build relationships with tribal leaders in these communities. Thus far, the northeastern Syria response has been fundamentally based on interaction with the Kurdish Self Administration; tribesmen are perhaps beneficiaries, but are not considered to be key stakeholders. Anecdotally, Arab tribes are rarely engaged without the facilitation of the Kurdish Self Administration, and little attempt is made to understand local tribal politics in a meaningful way. Tribal engagement must become a major component of the northeastern Syria humanitarian response, or risk jeopardizing longer-term interventions through the broad perception that humanitarian actors are aligned with and indistinguishable from the Kurdish Self Administration (and their shared donors).

- Institutional donors and INGOs should consider the potential longevity of their ongoing programs in northeastern Syria, especially in areas where regional actors, such as Turkey, clearly intend to build influence locally. This is especially true in the case of border communities such as Ras El-Ain, Tell Abiad, and Menbij, and is also especially true when these programs require close coordination with the Kurdish Self Administration.

- Organizations working in northeastern Syria must examine their security SOPs, contingency planning, and strategy, and prepare for a more unstable and unpredictable operating environment. Regional actors are building influence with Arab tribes partially in order to destabilize the Kurdish Self Administration; therefore, increased protests, targeted assassinations, and politically-motivated violence are likely to become more prominent feature of northeastern Syria’s landscape.

- Care must be taken with regard to attributions of a resurgent ISIS; violence perpetrated by discontented Arab tribes and violence committed by ISIS are very different. Fears of a resurgent ISIS are naturally in the minds of many government and non-governmental organizations working in Syria’s northeast. Northeastern Syria’s Arab tribes, incentivized by local and regional governments are likely to seek to destabilize northeastern Syria; at the same time, many Arab tribes have legitimate grievances against the Kurdish Self Administration. It is thus important to distinguish drivers of violence and instability to ensure an appropriate response. There is a real risk that all Arab violence will be presented as a ‘resurgent ISIS,’ and that this would lead to an international response that may ultimately empower extremist groups and ideologies in northeastern Syria.