Syria Update

September 05 to September 11, 2019

The Syria Update is divided into two sections. The first section provides an in-depth analysis of key issues and dynamics related to wartime and post-conflict Syria. The second section provides a comprehensive whole of Syria review, detailing events and incidents, and analysis of their respective significance.

Driven by External Factors, Lira’s Rapid Depreciation Likely to Widen Gaps in Syrian State’s Fiscal Capacity

In Depth Analysis

On September 9, the unofficial market exchange rate for the Syrian lira (SYP) ended three weeks of progressive decline and sank to its lowest-ever value: 690 SYP/USD. Although the lira rebounded to 665 SYP/USD on September 10, the currency has nonetheless shed approximately 10 percent of its value since August, and fears are widespread that Syria’s currency may be entering a cycle of extreme volatility which authorities have few means of mitigating. Indeed, despite the widening gap between the black market and official exchange rates (the latter of which remains fixed at 434 SYP/USD), there are no indicators that the Central Bank will adjust its monetary policy or official rate; moreover, it is widely believed that Syria’s foreign currency reserves are highly depleted, and in June, Syrian Central Bank Governor Hazer Qarful effectively signaled that the Central Bank is unlikely to take additional measures to cushion a freefall in the value of the Syrian lira (see: COAR Syria Update for June 20-26). The Central Bank’s approach in this regard is highly consequential: indeed, the value of the lira is considered one of the key metrics of the health of the Syrian economy overall.

These questions reflect deep uncertainty over the long-term prospects for the Syrian economy, specifically its susceptibility to external shocks. Indeed, the proximate causes of the latest runaway depreciation in the lira are, to a large extent, beyond the remit of the Syrian state to remedy. The most significant of these triggers are likely the increasingly restrictive international measures targeting the Syrian financial sector, the mounting economic toll of the sanctions targeting Iran, and the surging demand for dollars in Lebanon.

First, tightening U.S. restrictions on the Syrian financial sector have been instrumental in stemming the flow of dollars to the Syrian Government. On September 8, it was reported that money transfer agents in the UAE and Saudi Arabia had recently ceased transferring remittances to Syria using local currencies, thus depriving the Syrian Government of much-needed foreign currency infusions, allegedly due to the threat of potential legal ramifications raised by U.S. sanctions. Much attention has been given to the Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act; although the bill has not become law, its provisions for sweeping sanctions against international actors who deal with the Government of Syria make it a powerful deterrent. However, myriad related sanctions are already in effect. Indeed, on August 29, the U.S. Treasury Office of Foreign Assets Control sanctioned Lebanon’s Jammal Trust Bank, claiming the bank “knowingly facilitates banking activities for Hezbollah” and violates U.S. restrictions on conducting business with “the Government of Syria and its supporters.” Moreover, OFAC is now reportedly accelerating the process for registering individuals and entities on the U.S. Treasury sanctions list.

Second, the dire economic conditions in Iran have also had a considerable impact on Syria. On September 5, local sources in the Damascus industrial sector stated that Iran had frozen its credit lines to Syria, including credit lines for oil, medicine, and flour, forcing the Government to use foreign currency to make these purchases. In the past, Iran has temporarily suspended this vital support in order to pressure the Syrian Government. However, the current suspension must be seen in the context of Iran’s own deep economic challenges, which are directly linked to the U.S. sanction and isolation campaign designed to contain Iran’s influence regionally. To wit, on September 4, OFAC issued updated guidelines concerning its restrictions on Iran’s international oil shipping network.

Third, the collapse of the Syrian lira since August is almost certainly linked to the instability in the Lebanese economy, which is deeply intertwined with that of Syria. Indeed, Lebanese financial institutions are reported to be the primary outlet for Syrian importers seeking to conduct international financial transactions. However, Lebanon’s long-standing economic woes have created significant political and social tensions domestically, and driven up demand for dollars (including from Syrian investors seeking high returns in dollar deposits). On September 2, these tensions culminated with a statement from Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri, declaring a ‘state of economic emergency’ in Lebanon, heightening widespread speculation that the Lebanese Central Bank will allow the Lebanese lira to float on the open market. In turn, this has fueled even greater demand for dollars and put downward pressures on both the Syrian and Lebanese currencies.

Of the immediate consequences of the lira’s deepening instability, the most important is the substantial and continuous erosion of the purchasing power of Syrian consumers. The current market exchange rate represents a decline of approximately 35 percent since January 2019, when the exchange rate for the lira sat at 500 SYP/USD. The lira’s depreciation continues to drive up the price of commodities, such as food and, in northeast Syria, fuel. Anecdotally, household debt has skyrocketed, and economic anxiety on the part of Syrian wage earners is now rampant, especially among state employees, whose salaries have not been revised since the beginning of the conflict. Rumors are now widespread that low-denomination Syrian banknotes will be withdrawn from circulation, and in the absence of action by the Syrian Central Bank, a freefall in the value of the Syrian lira remains distinctly possible.

So far, as the long-term trajectory of the Syrian economy is concerned, the declining value of the lira will have acute consequences for state finances. Most notably, the Government of Syria accounts its budget in lira; as a result, the currency’s depreciation continues to widen the gap that exists between budget allocations and the actual fiscal capacity of the state, both at central and local levels. This widening gap will further complicate long-term budgeting by the state and heighten the shortfall in service provision, local administration, infrastructure rehabilitation, and developmental activities. Such shortcomings have been key drivers of conflict and instability (most notably in southern Syria, but also throughout the country). In the long term, however, these gaps are unlikely to remain unfilled. Private sector and state-linked actors from both Russia and Iran have undertaken activities in various service and economic sectors in Syria, and local businessmen are also likely to see the economic potential in filling these gaps. However, it is also the case that these gaps will remain a potential space for engagement by humanitarian or developmental actors, while the enormity of these needs is likely to provide significant latitude for shaping the trajectory of communities in Syria.

Whole of Syria Review

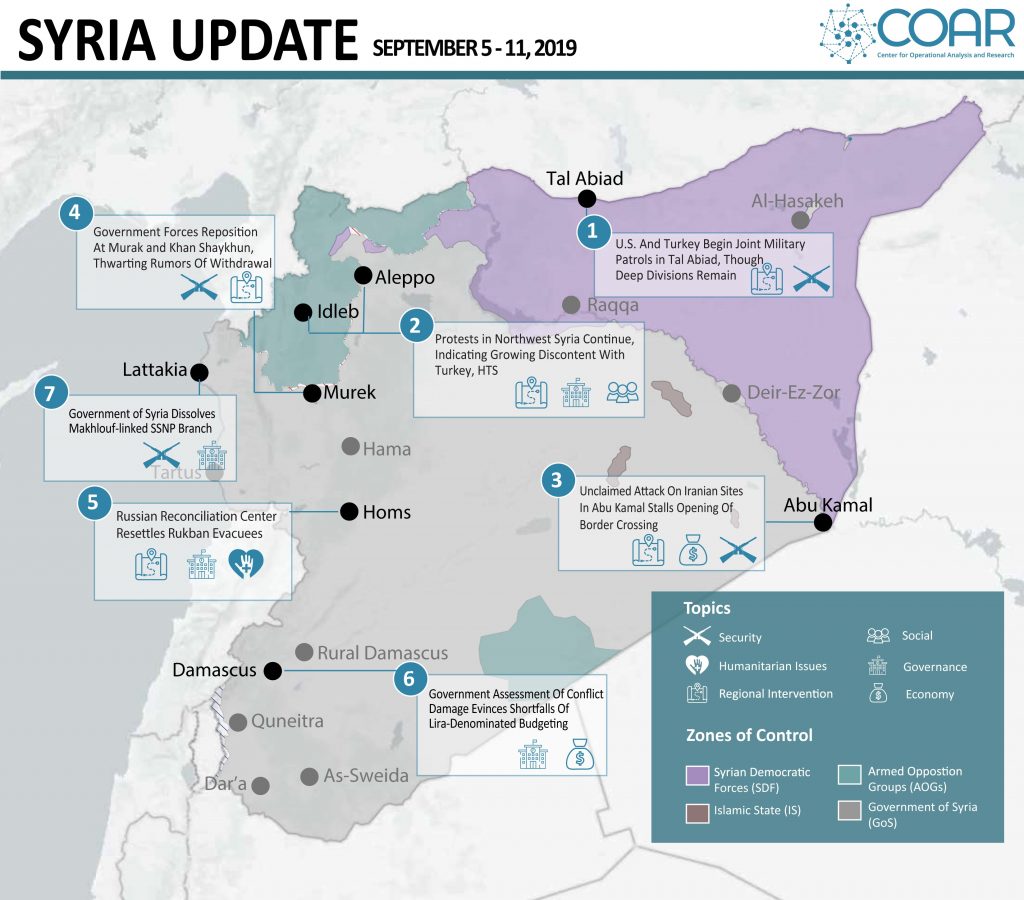

1. U.S. And Turkey Begin Joint Military Patrols in Tal Abiad, Though Deep Divisions Remain

Tal Abiad, Ar-Raqqa Governorate: On September 8, U.S. and Turkish forces conducted the first joint military patrol along the Syria-Turkey border, near Tal Abiad in northern Ar-Raqqa Governorate. Although the patrol marked the first time Turkish soldiers entered Syria under the auspices of the northeast Syria ‘safe zone’ deal, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan reportedly stated that current measures to implement the agreement will be “insufficient” if they limit Turkey’s involvement to “3-5 helicopter flights, 5-10 vehicle patrols, and a few hundred soldiers in the area.” Erdogan warned that if the ‘safe zone’ agreement “with Turkish soldiers is not initiated by the end of September, Turkey has no choice but to set out on its own.” Nonetheless, on September 9, U.S. Central Command stated that “the U.S. and Turkey are working together to rapidly implement the security mechanism and are on time or ahead of schedule in many areas.”

Analysis: The fact that the 1998 Adana agreement is being seriously considered as a negotiating framework isAnalysis: As the first joint U.S.-Turkish patrol carried out under the aegis of the northeast Syria ‘safe zone’ agreement, the maneuver is a symbolically important advance for Turkey. It also defies many analysts’ expectations regarding the implementation of the agreement, particularly the highly fraught nature of the partial withdrawal of YPG units from some border areas. However, it is important to note that despite this progress, the most contentious and impactful issues at stake between the U.S. and Turkey remain largely unresolved, and there are no indicators that these positions will be reconciled quickly. To this end, the divergence between U.S. and Turkish statements regarding the current progress in implementing the ‘safe zone’ are indicative of the wider gulf that continues to separate the parties’ fundamental positions vis-a-vis the depth and breadth of the ‘safe zone’. For instance, Erdogan continues to advocate for a ‘safe zone’ reaching as far as 32 km into northeast Syria, a position which is deeply at odds with the SDF position that the ‘safe zone’ area spanning the length of the border run to a depth of 5 km, and range between 9 and 17 km in sparsely populated areas between Tal Abiad and Ras Al-Ain. More fundamentally, however, it is also crucial to note that Turkey continues to view the YPG with deep-seated suspicion and as a threat. As noted in previous COAR Syria Updates, that view is unlikely to change, irrespective of the dimensions of the ‘safe zone’. As such, short of launching a full-scale military invasion of northeast Syria, Turkey is unlikely to find the means to satisfy its strategic ambitions with regard to the YPG. As a result, heated rhetoric on the part of Turkey is likely to continue, but as long as U.S. forces remain in northeast Syria, Turkey remains unlikely “to set out on its own.” of extreme importance to the ultimate trajectory of northeastern Syria. The 1998 Adana agreement required that the Government of Syria pledge to prohibit the activities of the PKK in Syria; by citing the Adana agreement as a political framework for the Governments of Syria and Turkey, Russia has indicated a willingness to support the Turkish position with respect to the YPG/PYD, the primary military and political groups within the Kurdish Self Administration. Additionally, the apparent involvement of Ahmed Jarba and Masoud Barzani indicates that some form of a Turkish-Russian brokered agreement, likely one which marginalizes the Kurdish Self Administration, may be forthcoming; Jarba has continuously advocated for a northeastern Syria tribal force, and Barzani has also reportedly agreed to use Iraqi Peshmerga forces to help secure a northeastern Syria ‘safe zone,’ and both are known to be aligned with the Government of Turkey. Therefore, the negotiating position of the Kurdish Self Administration continues to diminish vis-a-vis ongoing discussions with the Government of Syria on the ultimate status of the Kurdish Self Administration as a governance body.

2. Protests in Northwest Syria Continue, Indicating Growing Discontent With Turkey, HTS

Idleb and Aleppo Governorates: Throughout the reporting period, local and media sources reported that popular demonstrations continue against Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham in communities throughout Idleb Governorate, and in several communities in northern rural Aleppo Governorate. Throughout the protests, demonstrators reiterated their demand for the removal of HTS, and they once again condemned the Government of Turkey and its cooperation with Russia over the status of northwest Syria. In response to the large-scale mobilizations, HTS deployed a limited number of security forces to contain the growing popular unrest directed against it throughout northwest Syria, and the group has mounted (comparatively modest) counter-demonstrations of support. Moreover, following the massive August 29 demonstration at Bab Al-Hawa border crossing, on September 6, HTS reportedly closed all roads leading to Bab Al-Hawa. In addition to tightening security measures, HTS commander Abu Mohammad Jolani also conducted a meeting with shura council members, tribal leaders, and local notables at Bab Al-Hawa, during which Jolani accused the demonstrators of having linkages to Government of Syria reconciliation committees.

Analysis: It is important that current dynamics in northwest Syria be understood both through the lens of broader military operations and through the lens of local, community dynamics. While the international dimensions of northwest Syria are essentially the remit of Russia and Turkey, the most pertinent considerations in many communities concern the current and future role of HTS. Maintaining popular legitimacy is a priority of almost existential concern for HTS, and although HTS remains entrenched, and even popular among a considerable segment of the population of northwest Syria, this popularity has limits, and the group’s local acceptance has increasingly been openly challenged in recent weeks. The primary trigger of the open demonstrations is the widely held belief that HTS control over northwest Syria has come to be seen as a liability both by jeopardizing humanitarian and developmental programming, and as international actors increasingly look to HTS as the chief impediment to implementing the Idleb de-escalation agreement (and ultimately resolving the status of northwest Syria). As such, popular mobilizations against HTS are an important signal that HTS may be challenged both from above, by Turkey and perhaps the Government of Syria, and from below, in local communities and potentially by other armed opposition groups. In the narrow sense, the future momentum and impact of the popular demonstrations against HTS are contingent on HTS’s willingness to resort to violence to quell these demonstrations, and the possibility of widening Government of Syria shelling, which resumed on September 8, following an eight-day ceasefire implemented by Russia. In the long term, however, the sustainability of ongoing humanitarian and developmental programs in northwest Syria will hinge upon the outcome of negotiations between Turkey and Russia (see point 4 below).

3. Unclaimed Attack On Iranian Sites In Abu Kamal Stalls Opening Of Border Crossing

Abu Kamal, Deir-ez-Zor Governorate: On September 8, media sources reported that a series of aerial attacks targeted sites affiliated with Iran in Abu Kamal, Deir-ez-Zor Governorate, killing 18 Iran-linked combatants. No actor has claimed responsibility for the attacks. Several sites were reportedly targeted, including the newly established military border crossing in Abu Kamal, as well as other positions in Abu Kamal city and its vicinity. The strikes followed several weeks of renewed discussions over the reopening of the Abu Kamal-Al-Qaim commercial crossing with Iraq. On September 9, a member of the Anbar Governorate Council, Farhan Mohamad Al-Doleimi, stated that the opening of the Abu kamal-Al-Qaim crossing would be delayed until September 10, as preparations remain incomplete.

Analysis: Although no actor has claimed responsibility, it is highly probable that the aerial attacks in Abu Kamal were carried out by U.S. or Israeli forces. Israel has frequently conducted airstrikes in Syria targeting positions linked to Iran, and in recent weeks, these attacks have become increasingly brazen and wider in scope, and included targets in Lebanon and Iraq. As for the U.S., efforts to contain Iran’s military presence in Syria lie at the very core of U.S. military objectives in the region. Increasingly, U.S. policymakers have stated that efforts to confront Iran are a key factor in the continued U.S. troop presence in northeast Syria and the At-Tanf border crossing in southern Homs Governorate, which lies along the vital Damascus-Baghdad highway. In this context, it is important to note that the Abu Kamal-Al-Qaim border crossing is a node along a potentially lucrative commercial artery linking Iraq with Syrian territory held by the Government of Syria. As such, restoring the crossing remains a shared priority for Syria and Iraq, as well as Iran. Indeed, in March, the Iranian, Iraqi, and Syrian chiefs of staff convened a trilateral summit in Damascus to resolve issues standing in the way of restoring commercial traffic through the crossing. In the months since, Iraqi officials have repeatedly stated that the crossing will be opened imminently. The U.S. has reportedly exerted pressure on Iraq to prevent the opening of the crossing; now, the possibility of further airstrikes makes opening the crossing in the foreseeable future a dubious prospect.

4. Government Forces Reposition At Murak and Khan Shaykhun, Thwarting Rumors Of Withdrawal

Murak, Hama Governorate: On September 11, media and local sources reported that a widely rumored withdrawal of Government of Syria forces from positions in Murak and Khan Shaykun in northern rural Hama on September 10 did not take place. Rather, as of September 11, Government forces have repositioned and redeployed within the areas. The rumored withdrawal coincided with the widespread understanding regarding a Russian-Turkish agreement on northwestern Syria, and it had been strongly rumored that joint Russia-Turkish patrols would take place in areas from which Government forces would withdraw. Notably, Government of Syria forces took control of Murak and Khan Shaykun in late August, when armed groups backed by Turkey retreated from frontlines in northern Hama following prolonged aerial bombardment and heavy assault by Government forces. However, Turkish forces have retained their position at the observation point in Murak even after it was entirely surrounded by Government forces.

Analysis: The rumored Government withdrawal from portions of northern rural Hama was seen as a strong signal of Russia and Turkey’s willingness to steer a course toward de-escalation in northwest Syria. Such a withdrawal is, at least for now, not ongoing, and the prospect of a wider de-escalation is highly uncertain. In effect, the rumored Government withdrawal buffeted hopes that Russia and Turkey would create a buffer zone between Government- and opposition-held areas in northwest Syria and uphold the terms of the Sochi agreement of September 17, 2018. In essence, the agreement averted a large-scale Government of Syria offensive in Idleb by offering a roadmap for de-escalation. Key terms of the agreement stipulated the creation of a buffer zone of 15-20 km from which all opposition groups should withdraw; resumed access to primary transit routes (i.e. the M5 and the M4, the Hama-Aleppo and Latakia-Aleppo highways, respectively); and the removal of ‘terrorist’ groups (i.e. HTS). However, Turkey has been incapable of implementing the agreement by coercing HTS to withdraw from the buffer zone and/or forcing the group to dissolve. Now, the immediate trajectory of the military offensive in northwest Syria is highly uncertain, and a resumed Government of Syria military offensive, especially in areas surrounding M4 and M5, remains within the realm of possibility.

5. Russian Reconciliation Center Resettles Rukban Evacuees

Homs governorate: On September 8, media sources reported that Russia has allowed more than 300 Rukban camp evacuees to return to their home communities in Homs governorate, after they reportedly spent several months in collective shelters in Homs city. The returnees are among Rukban residents who have fled the camp since Russia opened humanitarian corridors in February. Most evacuees from Rukban were permitted to return to their areas of origin directly from the camp following reconciliation and other screening processes; nonetheless, some evacuees have been held in the shelters indefinitely. Indeed, Rukban evacuees have been subjected to security screening procedures that vary with respect to their community of origin, as well as their political and military background. For example, IDPs from Qaryatein, Mahin and surrounding areas have reportedly returned to their areas, while those from Tadmor were denied return under the pretext that Tadmor remains a military area.

Analysis: The return of IDPs from the shelters in Homs city highlights one of the key dynamics with bearing on return in Syria: the importance of intermediaries as brokers of return. Indeed, due to extremely restrictive security policies that limit mobility and access, for many Syrian IDPs, return to communities of origin is often effectively impossible. It is important to note, however, that in the absence of a coherent national policy guiding returns procedures, return remain highly localized, as evidenced by the fact that IDP returns are frequently contingent upon communities of origin, in addition to individual characteristics and identity. As such, the intervention of an outside actor such as Russia (or other local notables with connections or access to the Syrian state) is virtually required to broker return movements of any considerable size, such as the 300 Rukban evacuees held in Homs city shelters. However, the role of intermediaries does have important limitations: although intercession by an intermediary may be necessary to broker return on any large scale, it does not resolve further protections concerns. Indeed, even after reconciliation with the Government of Syria, returnees, including the Rukban evacuees now released from the shelters in Homs, remain vulnerable to further security screenings (for example, at border crossings and checkpoints), potential civil legal actions, reprisal, arbitrary detention, and conscription. For this reason, it is crucial that returns be viewed not only as a single bureaucratic step to facilitate return, but as a highly involved, ongoing process of reintegration into the Syrian state apparatus which is likely to remain ongoing for the foreseeable future.

6. Government Assessment Of Conflict Damage Evinces Shortfalls Of Lira-Denominated Budgeting

Damascus, Syria: On September 8, Syrian Prime Minister Imad Khamis stated that the Syrian Government’s preliminary assessment of damage to state sectors and institutions as a result of the Syria conflict totals 45 trillion SYP (67 billion USD, at the lira’s valuation as of September 10). Details regarding the exact methodology and geographic scope of the assessment were not reported. However, Khamis stated that 28,000 governmental buildings have been damaged, in addition to 188 state-owned enterprises and industrial facilities.

Analysis: Given that Khamis’ statement disclosed little about the methodology behind the Government’s findings, the actual utility and accuracy of the assessment are in question. The exercise is nonetheless important in its own right, as damage assessments of this kind will essentially frame the Syrian Government’s preliminary approach to rehabilitation and reconstruction. To this end, arguably the most important single dimension of the assessment is that it tabulates damages in Syrian lira. Indeed, given the dramatic instability in the market value of the lira, the fact that the Government produces its budget using lira represents a consequential challenge to its ability to establish a credible (or implementable) roadmap for rehabilitation and reconstruction (See in-depth analysis section above for further information on the rapidly shifting value of the Syrian lira). Indeed, the real value of the lira has declined by approximately one-third since the beginning of 2019; as a result of the ongoing and progressive depreciation, lira-denominated assessments, and budgets, rapidly fall out of date. Moreover, not only has the lira seen decline in its market value, its value continues to fluctuate widely. Finally, it is important to note that another factor renders such assessments progressively out of date: the ongoing offensive in northwest Syria. Indeed, so long as the active conflict continues, an accurate tabulation of the costs of the Syrian conflict will remain elusive.

7. Government of Syria Dissolves Makhlouf-linked SSNP Branch

Lattakia Governorate: On September 6, media sources reported that the Government of Syria has ordered the dissolution of a Lattakia Governorate branch of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP) that is headed by a cousin of Rami Makhlouf; the measure coincides with reported efforts by Government intelligence forces to pressure the board members of Al-Bustan Organization, also linked to Makhlouf, to step down from their positions and hand over operations to a newly appointed board. Notably, two SSNP branches (Al-Markaz and Al-Amana) are present in Lattakia, each of which maintains an armed wing that operates in ostensible violation of Syria’s multi-party law, which forbade political parties from managing associated military branches. Although Government forces have reportedly closed down the offices of Makhlouf-linked Al-Amana branch and urged its members to seek membership with Al-Markaz, yet the Al-Markaz branch has maintained its military force, Nosour Al-Zawba’, which was not targeted by the Government.

Analysis: The Government of Syria’s dissolution of the SSNP’s Al-Amana branch and its mounting pressure campaign on Al-Bustan Organization are particularly notable in light of widely rumored Government actions targeting Rami Makhlouf, including his businesses interests, Al-Bustan Organization, and now, reportedly, political entities as well. It is extremely noteworthy that these initiatives are now visible in Lattakia, where Makhlouf has enormous popularity, both as a result of inherited status and his own patronage networks; indeed, in many coastal communities, Makhlouf’s power rivals that of president Bashar Al-Assad. Naturally, the new initiatives targeting Makhluf highlight the Government’s determination to centralize and institutionalize its authority within the state structures, which have been a leitmotif of internal Government restructuring throughout 2019. The most visible of these are initiatives (apparently driven by Russia) to dismantle and remobilize nominally pro-Government paramilitary groups, contain the influence of warlords, and reshuffle the most senior military and security positions within the Syrian state apparatus itself.

8. Syrian Embassy in Oman Now Conditioning Passport Renewal On ‘Reconciliation’

Muscat, Oman: On September 4, media sources reported that employees at the Syrian embassy in Muscat, Oman, have imposed new conditions upon the renewal or issuance of new Syrian passports, requiring that requestors reconcile with the Government of Syria. In addition to requiring individuals to sign reconciliation papers, embassy employees have also made passport-related requests conditional upon the individuals’ disavowal of ‘terrorist’ organizations. Finally, the procedure reportedly requires the requesters to place guilt for any death among their family members during the conflict on ‘terrorists,’ thus absolving the Government of Syria of any guilt. Notably, both men and women have reportedly been affected by these procedures, and those declining to sign the papers are refused service.

Analysis: Although they are not surprising in their own right, the conditions imposed on the issuance of new Syrian passports in Oman are the first of this kind to be reported. It is difficult to assess whether such procedures will be (or have previously been) imposed at other Syrian diplomatic missions; however, it is clear that for Syrians abroad, the imposition of such measures is a worrying development in that it raises the potential cost of conducting any kind of business with the Government of Syria. In the long term, if these procedures are replicated in other contexts, they will necessarily exacerbate an already precarious situation for Syrians residing outside Syria. In effect, by imposing further barriers to administrative and screening procedures outside Syria, the Government of Syria presents Syrians abroad with difficult decision points regarding their ability to return to Syria. In effect, Syrians will likely be forced to weigh the risks entailed in interacting with Government apparatuses (including the risk of detention, fines, or other future punitive measures as a result of the ambiguity inherent in these procedures), or resort to other measures that evade these entities altogether, including by seeking asylum.

The Wartime and Post-Conflict Syria project (WPCS) is funded by the European Union and implemented through a partnership between the European University Institute (Middle East Directions Programme) and the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR). WPCS will provide operational and strategic analysis to policymakers and programmers concerning prospects, challenges, trends, and policy options with respect to a conflict and post-conflict Syria. WPCS also aims to stimulate new approaches and policy responses to the Syrian conflict through a regular dialogue between researchers, policymakers and donors, and implementers, as well as to build a new network of Syrian researchers that will contribute to research informing international policy and practice related to their country.

The content compiled and presented by COAR is by no means exhaustive and does not reflect COAR’s formal position, political or otherwise, on the aforementioned topics. The information, assessments, and analysis provided by COAR are only to inform humanitarian and development programs and policy. While this publication was produced with the financial support of the European Union, its contents are the sole responsibility of COAR Global LTD, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.