‘Land Swaps’: Russian-Turkish Territorial

Exchanges in Northern Syria

14 November 2019

Home » Syria » Thematic Reports » ‘Land Swaps’: Russian-Turkish Territorial Exchanges in Northern Syria

Executive Summary

The recently announced Turkish-Russian Memorandum of Understanding, signed on October 22, has essentially granted Turkey direct control over a large segment of northeast Syria. Naturally, the Turkish incursion into northeast Syria has and will continue to have a massive impact on local political dynamics in that region. However, here it is worth bearing in mind the secondary components of past Turkish military actions in Syria – specifically, the distinct correlation between Turkish military offensives and subsequent or simultaneous Government of Syria offensives.

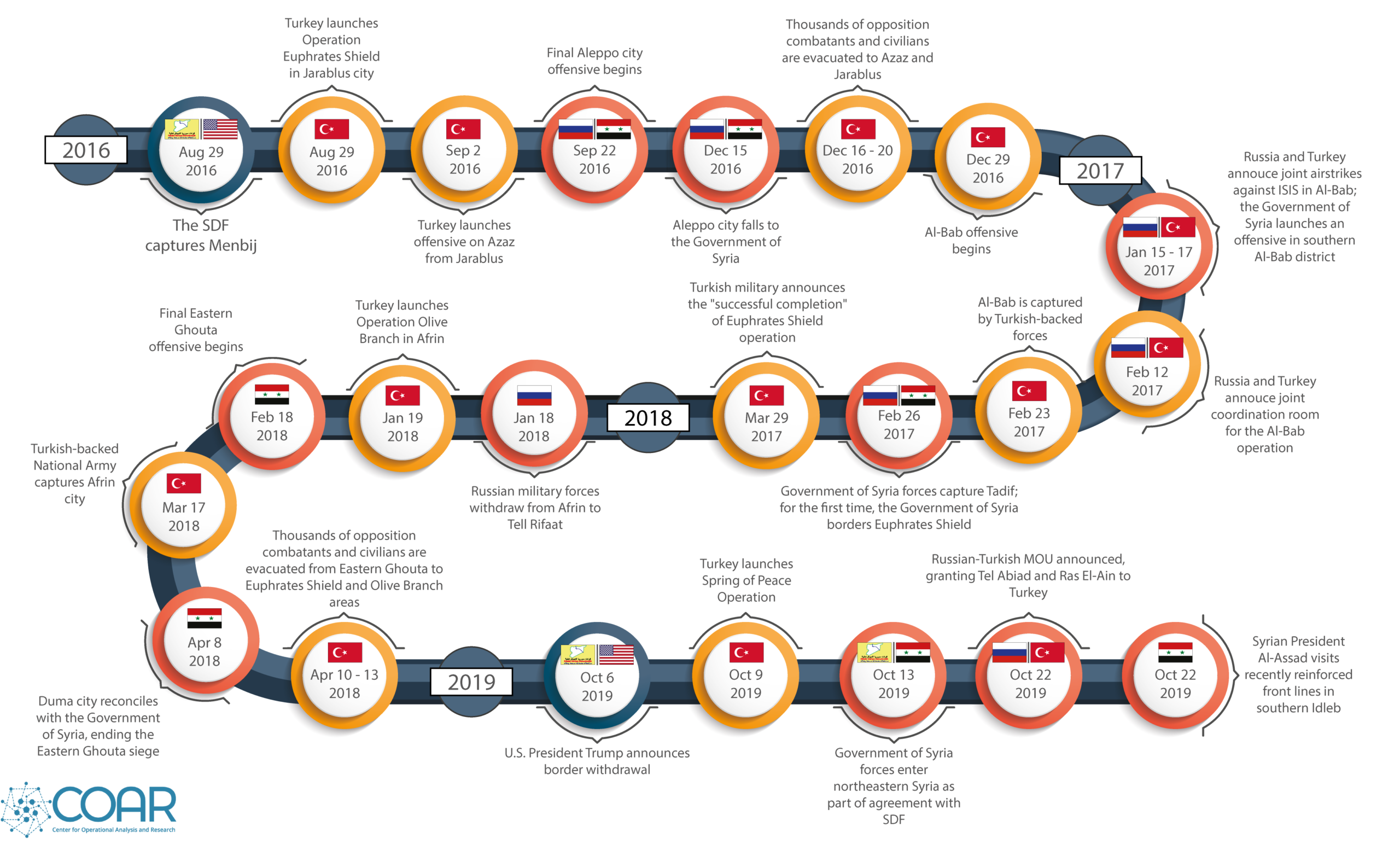

Since late 2016, almost every major Turkish military operation has been ‘paired’ with a major Russian-backed Government of Syria offensive. The start of Operation Euphrates Shield began only weeks before the government siege intensified in Aleppo city; the Turkish military operation in Al-Bab city, which was indirectly assisted by Government of Syria military forces, came only weeks after the fall of eastern Aleppo city; and the Turkish-backed Operation Olive Branch in Afrin was concurrent with the Government of Syria offensive on Eastern Ghouta. Many Syria analysts have referred to this trend as a form of ‘land swap’ – effectively, Russia and Turkey granting each other ‘permission’ to take control of an area, or facilitating offensives on different parts of the country. Certainly, the term ‘land swap’ is an overly simplistic abstraction for what is a component part of the constantly evolving Turkish-Russian relationship in Syria; however, in practice this relationship does entail territorial exchanges to further larger geopolitical ambitions.

The extent to which a similar dynamic is at play in northeast Syria is a subject of open debate. A ‘land swap’ agreement between Russia and Turkey may not always have been in place – few could have predicted U.S. President Trump’s decision to abruptly withdraw from the border in northeast Syria – however, considering the close working relationship between Russia and Turkey in Syria, a potential agreement should not be discounted out of hand. To that end, the Syria humanitarian and development response must consider the possibility that there may be a potential Russian-Turkish land swap agreement, and that this will involve heavy conflict and displacement in northwest Syria.

This short paper presents an examination of what COAR believes to be the most likely scenario: Turkish acceptance or facilitation of a Government of Syria offensive targeting northern Hama and the M5 highway region of northwest Syria, in return for territorial concessions that have already essentially been granted on the northeast Syrian border. This offensive will also potentially have a significant humanitarian impact, especially considering the fact that more than 300,000 individuals, almost a third of whom are IDPs, currently reside in the areas likely to be targeted by the offensive. The timing of this offensive is naturally impossible to predict – however, practitioners should assume that it will take place in the near term. Indeed, as of November 14, local and media sources have noted that the preliminary steps toward an offensive have already begun, and shelling has been reported along the front lines in eastern Idleb.

Territorial Exchanges: A Component of an Evolving Relationship

It is important to note that facilitating territorial exchanges should not be viewed as a simplistic quid-pro-quo. Turkey and Russia are two of the most influential regional actors in the Syrian conflict, and are the primary backers of the Syrian Interim Government and the Government of Syria. Both countries were partners in the Astana (now Nursultan) talks and the Sochi conference, are the primary guarantors of the (now largely defunct) de-escalation[footnote]In May 2017, Iran, Russia, and Turkey announced the Syria de-escalation zone agreement,[footnote]In September 2018, Turkish and Russian officials released a memorandum of understanding declaring a northwest Syria ‘disarmament zone. The memorandum declared a disarmament zone of 15-20 kilometers into opposition-controlled Idleb, whereby ‘radical’ opposition groups (namely, Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham) would withdraw from the zone, and opposition groups remaining in the zone would remove their heavy weapons from the area. Despite several Turkish attempts, the terms of the agreement have never been meaningfully implemented: both Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham, and armed opposition heavy weapons remain within the disarmament zone.[/footnote] whereby Eastern Ghouta, northern Homs, southern Syria, and northwest Syria were declared as de-escalation zones and put under a ceasefire. Since that time, Eastern Ghouta, northern Homs, and southern Syria have all been recaptured and ‘reconciled’ through major government offensives.[/footnote] and disarmament zone agreements, and are deeply involved in the Syria constitutional committee process.[footnote]It must be repeatedly emphasized that the Turkish-Russian relationship goes far beyond the Syrian conflict. Weapon sales (such as the S-400), Turkey’s role in NATO, commercial agreements, and the broader Turkish-Russian global posture are core components of this relationship. Territorial exchanges in Syria are ultimately only a small component of a specific dimplatic file, and should be considered as such.[/footnote] Both Turkey and Russia also have different (though not necessarily incompatible) priorities in Syria that are constantly adjusting to new events. Thus, territorial exchanges should not be seen as isolated agreements – they are instead a component part of a multifaceted and constantly evolving relationship in which both actors are seeking to accomplish specific objectives as part of more comprehensive geopolitical foreign policy objectives. To that end, Presidents Erdogan and Putin, as well as Russian and Turkish military and diplomatic counterparts, regularly meet and closely coordinate their Syria policy.

Here it is worth briefly examining the history of this relationship, and marking when the Turkish-Russian partnership in Syria first developed to the point of negotiating territorial exchanges: the SDF capture of Menbij city. In the summer of 2016, the SDF launched a major offensive against ISIS, crossed the Euphrates river, and captured Menbij city in August 2016. The SDF crossing the Euphrates had, up until this point, long been considered a ‘red line’ by Turkey, which had emphatically stated that it opposed the Menbij operation for months.[footnote]Perhaps even more provocative that the crossing of the ‘red line’ on the Euphrates river was the fact that the U.S. coalition pushed for the SDF offensive on Menbij to the exclusion of Turkey – indeed, regional geopolitical analysts often point to this event as the largest contributing factor in the deteriorating U.S.-Turkish relationship.[/footnote] The crossing of the Euphrates, and the capture of Menbij thus represented what had long been considered a nightmare scenario by Turkey: the potential that the YPG-led SDF, backed by the U.S.-led coalition, would capture large swaths of northern Syria from ISIS and potentially link SDF-held northeast Syria to SDF-held Afrin. From Turkey’s perspective, this would lead to a situation by which the entire Turkish-Syrian border was controlled by a group that Turkey considers to be indistinct from the PKK.

Euphrates Shield, Aleppo City, and Al-Bab

To that end, mere weeks after the capture of Menbij, Turkey announced on August 29, 2016 the start of Operation Euphrates Shield. Euphrates Shield was ostensibly an operation against ISIS, but in reality it was an extremely ambitious project to establish direct territorial control over northern Syria, likely viewed by Turkey as the only means of preventing SDF expansion across the border in the long-term. Reportedly, the start of Euphrates Shield was closely coordinated with Russia – a necessary step to allow Turkish warplanes to support the operation, especially considering that Turkey less than a year earlier had shot down a Russian warplane on the Syrian border.[footnote]The Turkish shootdown of a Russian jet in November 2015 in many ways marks the start of closer Turkish-Russian coordination in Syria. [/footnote] Indeed, President Putin himself commented on the start of Euphrates Shield that “Turkey’s operation in Syria was not something unexpected for us…We understood what was going on and where things would lead.”[footnote]https://www.worldbulletin.net/europe/turkeys-syria-operation-not-unexpected-putin-h177056.html [/footnote]

Concurrent with the start of Euphrates Shield was the ongoing, and largely stalemated, siege of Aleppo city. As the Euphrates Shield region expanded outward from Jarablus toward Azaz on September 22, 2016 the Government of Syria announced its ‘final’ offensive on Aleppo city. To this end, two key points are worth noting: the Turkish-backed armed opposition forces engaged in the Euphrates Shield operation were, at the time, facing serious military setbacks in their offensive against ISIS; and, a sizeable component of the armed opposition groups in Aleppo city were backed to some degree by Turkey. Many analysts thus point to the resolution of the Aleppo city siege, and the ‘completion’ of Operation Euphrates Shield as the start of a close Russian-Turkish partnership, with territorial exchanges and personnel evacuations being a key component of that partnership.

Essentially, over the course of October 2016 to March 2017, Turkey and Russia took a variety of steps to ‘exchange’ Aleppo city for northern Aleppo. This was accomplished by a variety of means: Turkey withdrawing its support to the armed opposition groups it had previously supported in Aleppo city;[footnote]Armed opposition groups and media representatives formerly in Aleppo city have regularly alleged that at the start of the Aleppo city offensive Turkish support to armed opposition groups in the city substantially decreased. As early as October 2016, the withdrawal of Turkish support as part of a potential ‘deal’ with Russia was speculated by many Syria analysts.[/footnote] Russian guaranteeing that selected armed opposition groups would be withdrawn to Euphrates Shield (thus, bolstering the military capacity of the Euphrates Shield operation); and finally, following the fall of Aleppo city, Russian and Government of Syria military indirectly supporting Operation Euphrates Shield in Al-Bab city.[footntoe]Almost immediately following the fall of Aleppo city, the Government of Syria launched an offensive against ISIS in southern Al-Bab, concurrent with ongoing Turkish-backed armed opposition military operations against ISIS in Al-Bab. Russia and Turkey conducted joint airstrikes, and established a joint operations room to manage the offensive. The Government offensive concluded when Government of Syria military forces captured Tadif, which joined Euphrates Shield to Government of Syria-held areas for the first time.[/footnote] There is no reason to assume that this ‘exchange’ was planned out in advance – in fact, it is more likely that sets of smaller agreements were reached based on changing conditions, such as the unexpected resistance of ISIS forces in Azaz and Al-Bab city, and the increasing likelihood that Aleppo city would fall to the Government of Syria with or without Turkish support. However, in effect the ‘template’ formed in Aleppo city and northern Aleppo should be seen as a potential model to inform how Russia and Turkey coordinate to achieve separate geopolitical objectives.

Eastern Ghouta and Afrin

The most cited case of a territorial exchange agreement between Turkey and Russia is in Afrin and Eastern Ghouta. Throughout late 2017, President Erdogan and Turkish officials regularly stated their intention to launch a new military operation against the YPG in Afrin, similar to the Euphrates Shield operation against ISIS. At this time, Russia had engaged in considerable outreach with the PYD, YPG, and the SDF. Indeed, the PYD maintained an office in Moscow since 2016, regularly engaged in high level negotiations with Russian officials, and Russian military observers were deployed in Afrin to mitigate conflict with the Turkish-backed opposition groups in Euphrates Shield. At the same time, late 2017 marked a significant escalation in the siege of Eastern Ghouta, whereby the Government of Syria was besieging armed opposition groups that were primarily backed by Turkey (primarily Jaish Al-Islam and Faylaq Ar-Rahman).[footnote]Faylaq Ar-Rahman, often linked to the Muslim Brotherhood, had reportedly been backed by Turkey since its creation; Jaish Al-Islam had reportedly began as a Saudi backed group, but by 2016 was primarily supported by Turkey.[/footnote]

In early 2018, Russian officials reportedly attempted to broker an agreement with the YPG in order to prevent a Turkish offensive, whereby Afrin would fall back under Government of Syria control. The YPG reportedly refused this proposal, and on January 18 the Russian military observers in Afrin withdrew to nearby Tell Rifaat; On January 19, Turkey military forces and Turkish-backed armed opposition groups launched Operation Olive Branch and entered Afrin, amidst heavy airstrikes and cross-border artillery.[footnote]SDF and PYD officials widely interpreted the Russian withdrawal of military observers as a betrayal. According to a PYD statement at the time: “We know that, without the permission of global forces and mainly Russia, whose troops are located in Afrin, Turkey cannot attack civilians using Afrin airspace.” Similarly, SDF spokesman Keno Gabriel stated that: “We agreed with Russia to observe Afrin on the peaceful principles, but it now allows Turkish warplanes to attack Afrin. It means Russia has betrayed us.” [/footnote]

As operation Olive Branch was underway, on February 18 the Government of Syria launched its final offensive on Eastern Ghouta. At that time, Eastern Ghouta was a ‘de-escalation’ area guaranteed by Russia, Turkey, and Iran; notably, throughout the Eastern Ghouta offensive Turkey issued relatively few condemnatory statements, despite its role as a guarantor and regular demonstrations against the Eastern Ghouta offensive in Istanbul. On March 17, Turkish-backed armed opposition groups captured Afrin city, the essential goal of Operation Olive Branch. Three weeks later, on April 8, the Government of Syria negotiated the reconciliation of Eastern Ghouta, reportedly with Turkish mediation; evacuations began on April 10, and ultimately at least 66,000 individuals were forcibly evacuated to northern Syria. Many of these evacuees from Eastern Ghouta were eventually relocated to Afrin – indeed, members of the Duma local council now sit on the Afrin local council – and both Jaish Al-Islam and Faylaq Ar-Rahman are now among the most prominent Turkish-backed groups in Afrin.[footnote]otably, both Jaish Al-Islam and Faylaq Ar-Rahman are taking part in the ongoing Spring of Peace operation in northeast Syria.[/footnote]

What Next?

Naturally, Turkey and Russia have not openly acknowledged previous agreements to exchange territorial control in Syria; such open acknowledgement would certainly be unacceptable to their partners inside Syria. However, the current situation in northeast Syria closely resembles the previous cases above. Turkey has launched a major military operation in northeast Syria, and as part of the Turkish-Russian MOU issued on October 22, Turkey has been effectively granted control over a large swath of land in the vicinity of Tel Abiad and Ras El-Ain – territory which Turkey views as critical to secure control over their southern border. The final extent of Turkish control in northeast Syria is still in question, and conflict is ongoing. However, Russia and the Government of Syria are certain to push for similar concessions in areas that they consider critical to their immediate strategic ambitions. To that end, the most likely area that Russia and the Government of Syria will attempt to ‘exchange’ in the near to medium term is in the northwest Syria de-escalation zone.

The Government of Syria has already made its intentions to launch a new offensive in Idleb quite clear. Throughout late October and early November there have been reports of increased Government of Syria deployments to southern Idleb and western Aleppo; indeed, President Al-Assad recently visited front lines in southern Idleb on October 22 (a solid indication of the Government of Syria’s priorities). President Al-Assad further stated in an interview with RT on November 11 that “the battle for Idlib will not take long,” emphasizing that Government of Syria forces are ready for an offensive. Also on November 11, Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov stated that “…all the hotbeds for terrorism are eliminated, and the only one remaining is in the Idlib region. This hotbed needs to be eliminated, and Turkey has to fulfill its obligation and distinguish between terrorists and the patriotic opposition,” again calling into question the future of the Idleb de-escalation agreement.[footnote]https://news.am/eng/news/543843.html[/footnote]

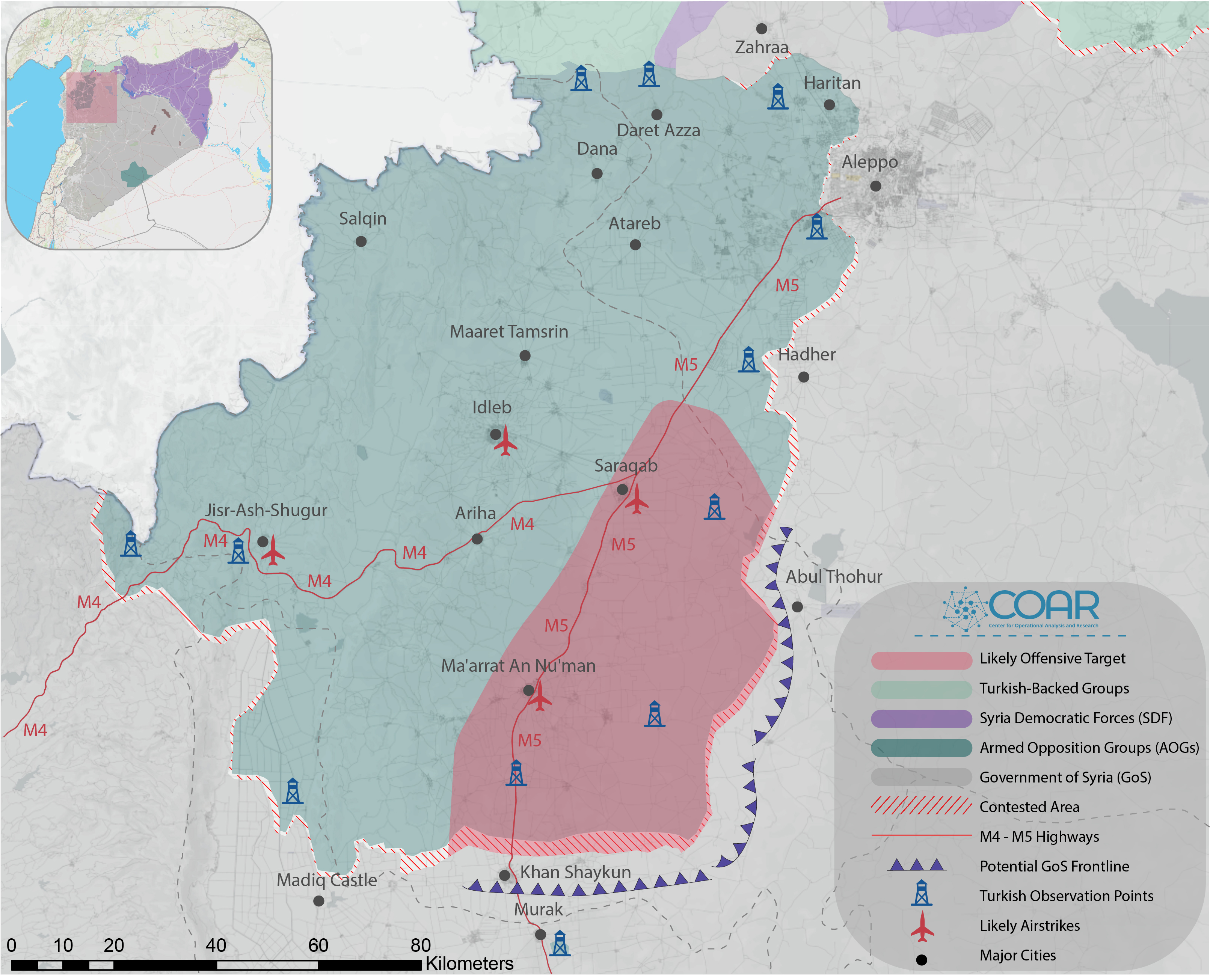

M5 Offensive - Ma’arret An Nu’man and Saraqab

To that end, the most likely location of any forthcoming Government of Syria offensive in northwest Syria is on segments of the M5 highway, and northern Hama. Control of the M5 highway, which links Aleppo city to Damascus and Dar’a, has been a longstanding strategic priority of the Government of Syria since the start of the conflict (and was an important stipulation of the now largely defunct ‘disarmament zone’ agreement). Moreover, several of the most important major communities along the M5 highway – Ma’arrat An Nu’man and Saraqab – are still, at least partially, controlled by Turkish-backed groups within the National Liberation Front, and Turkey thus wields considerable influence over the military trajectory of these areas. Therefore, considering their key locations along the M5 highway, Ma’arrat An Nu’man and Saraqab are likely to be the primary targets of any impending Government of Syria offensive.

According to local sources, many civilians in northern Hama, Ma’arrat An Nu’man, and Saraqab are deeply concerned about the prospect of an upcoming offensive – reportedly, some civilians in these areas are already preparing to displace. Additionally, other sources note rumors that Turkish and Russian officials are already coordinating on a potential northwest Syria offensive that may necessitate Turkey allowing Government of Syria forces to circumvent the Turkish observation points stationed in northwest Syria, and that some intelligence sharing is already taking place. Local rumors are certainly not a benchmark of accuracy; however, considering the timing of events nationally, they should not be discounted out of hand.[footnote]What should also be strongly considered is the fact that future Russian-Turkish territorial exchanges in Syria are almost certain to take place. Turkey will likely strongly push for control over Kobane, thus connecting Spring of Peace to Euphrate Shield; similarly, Russia and the Government of Syria will likely push for further concessions in Idleb. Similarly, Turkey will likely push for control over YPG-held Tel-Rifaat, south of Afrin; however, reportedly Iran has considerable interests in Tel Rifaat due to its proximity to the Shiite enclaves of Nubul and Zahraa, thus significantly complicating any agreement in this area.[/footnote]

Impact

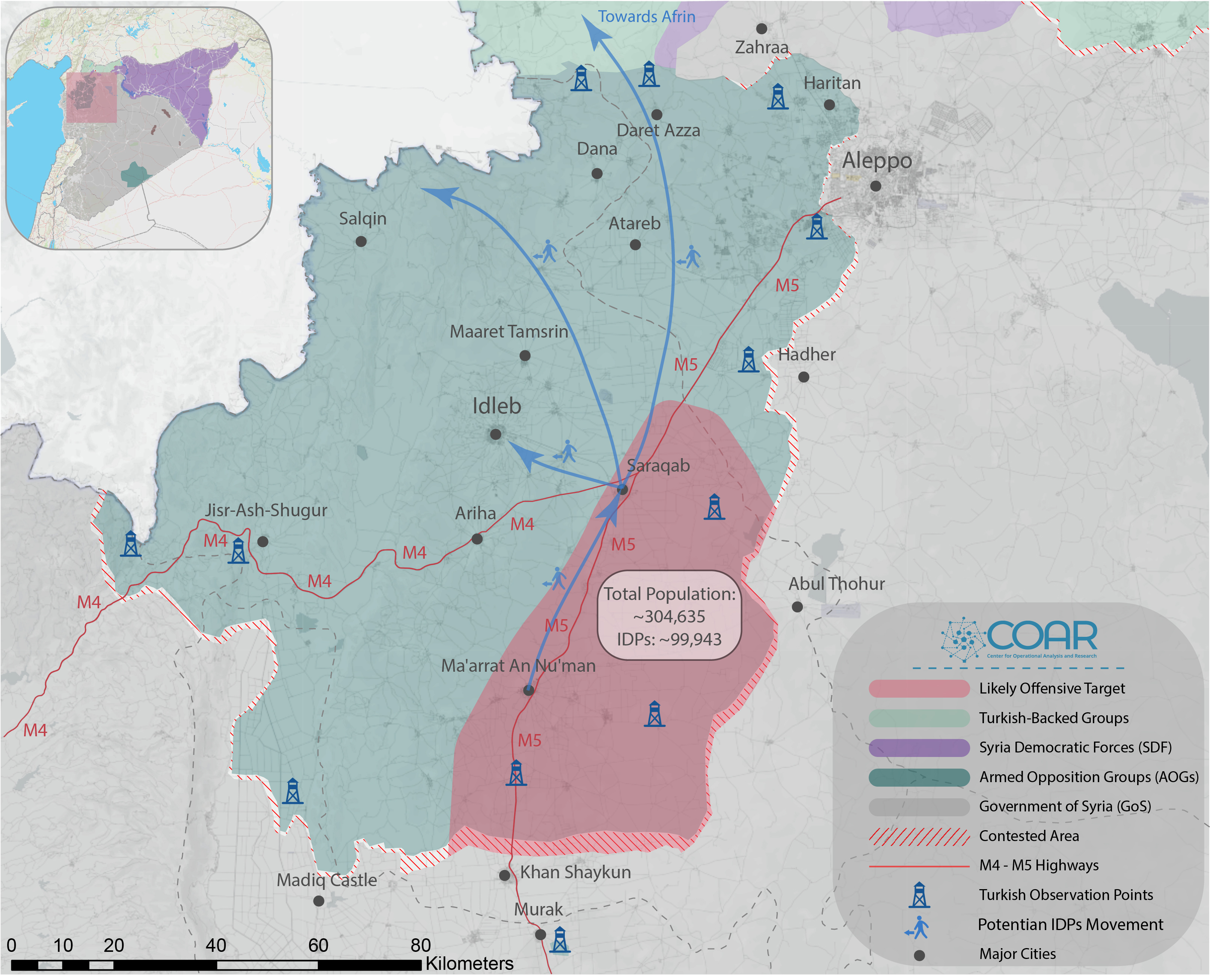

As noted, the area considered to be the most likely target of a major Government of Syria offensive is the southern M5 highway, to include the major communities of Ma’arrat An Nu’man and Saraqab. According to UN and local NGO partners, there are approximately 304,635 individuals living in the targeted M5 region of Idleb as of September 30, 2019; approximately 191,725 of these individuals are residents, and 99,943 are IDPs. In past northwest Syria offensives, between 60-80% of the resident population (and nearly all IDPs) tend to flee their communities either due to the conflict, or due to the fact that they are aware that they will not be permitted to reconcile with the Government of Syria. For that reason, response actors should consider the possibility that at least 250,000 individuals will flee from the areas targeted by the offensive alone. These individuals will likely flee to locations deeper into northwest Syria, such as Idleb city; to the Turkish border; or to Turkish-held Afrin, especially for those individuals and families that have linkages to Turkish-backed groups. Further displacement will likely take place throughout Idleb due to aerial attacks and shelling targeting communities throughout Idleb, a certain component of any major offensive.

The Wartime and Post-Conflict Syria project (WPCS) is funded by the European Union and implemented through a partnership between the European University Institute (Middle East Directions Programme) and the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR). WPCS will provide operational and strategic analysis to policymakers and programmers concerning prospects, challenges, trends, and policy options with respect to a conflict and post-conflict Syria. WPCS also aims to stimulate new approaches and policy responses to the Syrian conflict through a regular dialogue between researchers, policymakers and donors, and implementers, as well as to build a new network of Syrian researchers that will contribute to research informing international policy and practice related to their country.

The content compiled and presented by COAR is by no means exhaustive and does not reflect COAR’s formal position, political or otherwise, on the aforementioned topics. The information, assessments, and analysis provided by COAR are only to inform humanitarian and development programs and policy. While this publication was produced with the financial support of the European Union, its contents are the sole responsibility of COAR Global LTD, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.