Executive Summary

On 17 October, spontaneous mass protests broke out across Lebanon. While the protest movement remains essentially leaderless and predominantly aims to reshape the existing Lebanese political establishment, its immediate cause is the increasingly dire state of the Lebanese economy and the rapidly deteriorating value of the Lebanese lira (LBP). The persistent demands of the protest movement continue to center on the formation of a nonpolitical technocratic government. However, the existing Lebanese political establishment appears increasingly paralyzed. Thus far, it has been unable to address the protesters’ demands or form a unified government that is acceptable to the existing Lebanese political parties, further exacerbating the looming economic crisis. While these conditions are of the foremost importance for Lebanon’s own governance and stability, they have also caused increasing anxiety among those involved in the Syria crisis response — both because Lebanon is an important hub for the Syria response, and because of the knock-on effect on Syria itself.

Naturally, conditions in Lebanon have a large impact both on the estimated 1.5 million Syrians currently residing there and on Syria itself, which remains Lebanon’s most consequential neighbor, immediate political foil, and indispensable trading partner. Indeed, the political, economic, and social trajectories of Lebanon and Syria are deeply intertwined. Lebanon’s open-market economy and banking sector have long served as Syria’s primary economic and financial gateway to the world. Many Syrian individuals and businessmen deposit their money in Lebanese banks and depend, in their daily lives, on imports from Lebanon; this has especially been the case since the Syrian conflict erupted. Thus, as Lebanon approaches financial collapse and Lebanese private banks impose greater capital controls, Syria is drawn further into the Lebanese crisis. The devaluation of the LBP has contributed to inflation in the Syrian lira (SYP); import and export challenges have the potential to seriously impact economic and humanitarian conditions in both countries; Syrian workers and refugees in Lebanon now face new challenges both in gaining employment and in sending remittances to Syria; and the international response supporting Syrian refugees will face new challenges, sparking fears of premature or unstable returns to Syria.

This paper examines how the ongoing Lebanese crisis has already affected Syria and the international Syria response. As such, this paper does not focus on Lebanon, per se, nor does it attempt to forecast the possible outcomes of Lebanon’s highly fluid economic and political situation. Rather, this paper explores the impact of Lebanon’s crisis on Syria and the Syria response, particularly the economic impacts both inside Syria and on Syrian refugees in Lebanon; it offers a preliminary outlook on the emerging dynamics that are likely to impact these interconnected systems. Lebanon’s crisis shows little sign of ending, as political gridlock continues and economic conditions worsen. Considering how intertwined the economies and societies of Syria and Lebanon are, the Lebanese political crisis may well lead to a new phase in Syria and for the Syria response.

Key Takeaways

- Lebanon’s political deadlock is likely to compound the state’s inability to address its most urgent economic challenges. Forming a new government will require satisfying an array of conflicting interests, and only then will the government be able to undertake the more acutely challenging task of addressing the deepening economic crisis or meaningfully responding to the demands of the popular protest movement. Political gridlock, and deteriorating economic conditions may thus persist for months — or even years.

- Economic upheaval in Lebanon will have a predominantly negative impact on the Syrian economy, which will last for the foreseeable future. The most notable such impacts are the results of tightening restrictions on capital — including Syrian deposits — now held in Lebanese banks; the close linkage between the value of the deteriorating Syrian and Lebanese currencies; Lebanon’s collapse as an effective hub for the import of fuel, industrial gas, and iron to Syria; and labor market contraction, which will shrink the inflow of remittances to Syria.

- Due to Lebanon’s import challenges, Syrian agricultural producers will likely capitalize, to some extent, on heightened demand in Lebanon, as will exporters and smugglers. That said, there are already worrying signs that Syrian businessmen and smugglers may prioritize exporting goods to Lebanon over supplying domestic markets, thus causing shortages of key goods in Syria.

- Varied, highly localized dynamics will increasingly shape the space available to response actors in Lebanon. As such, local social conditions, programming, and access are likely to depend more and more on response actors’ relationships with the community in which they program and with relevant administrative and coordinating entities.

- Economic, social, and political conditions in Lebanon are visibly deteriorating. Lebanese host communities and Syrian populations alike are affected by these conditions, albeit in different ways. For Syrians in Lebanon, a notable potential outcome will be an increase in the pace of returns to Syria. In fact, anecdotal reports indicate that returns driven by the ongoing crises in Lebanon have already begun. However, the fact remains that many Syrian refugees are entirely unable to return to Syria, due to Government of Syria security policy, and are thus ‘trapped’ in Lebanon.

The Lebanese Political Landscape: Geopolitics and Gridlock

It is extremely difficult to speculate on the ultimate trajectory of the Lebanon uprising; however, it is safe to posit that the Lebanese political and economic crises are likely to become long-term issues that will be characterized by continuous political gridlock and persistent pressure from the Lebanese street, taking months or even years to resolve. The primary reason for this is the fact that Lebanon’s political architecture, while not overtly ‘authoritarian’, is designed to impede sweeping reform, and it imposes high thresholds to reach the political consensus needed to take even minor decisions. Lebanon’s current crisis must be taken into account when considering the economic and political landscape in Syria for the foreseeable future, as the two nations’ political, economic, and security dynamics are deeply interlinked.

The all-important structural impediments present within Lebanon’s governing framework have been glaringly apparent since the outbreak of the current crisis. On October 29, in response to the spontaneous popular protest movement that has gripped Lebanon since October 17, Prime Minister Saad Hariri resigned his office. Hariri’s resignation dissolved the Lebanese government, relegating it to caretaker status until a new prime minister is elected and a new cabinet formed. As a result of its caretaker status, the government is capable of implementing previously approved policy, but it is no longer invested with the authority to approve new policies. Thus, until a new Lebanese government is formed, the Lebanese state will be incapable of taking urgently needed steps to address the growing economic crisis or to meaningfully respond to the demands of the popular protest movement. There are yet further causes for concern. Considering the structural realities of the Lebanese political landscape, the process of forming a new government will be extremely challenging — and taking the politically fraught decisions needed to address the deep issues facing Lebanon will be even more challenging.

Here, it is important to note that the Lebanese political landscape is both overtly sectarian — as a consequence of the confessional political system — and geopolitical, in that political parties are broadly divided by their geopolitical orientation. In essence, there are two major blocs in Lebanese politics: political parties that are closely aligned with Iran and the Government of Syria, and political parties that are more inclined towards Western governments and Gulf states.[1]It is important to note that although this geopolitical division among Lebanese political parties has been a relatively fixed feature of Lebanese politics, several political parties regularly change … Continue readingThis division is most prominently manifested in political parties’ stances on the Hezbollah political movement — specifically, its ability to maintain its parallel status as a non-state armed group that continues to undertake an armed intervention in the Syria conflict — and on the restoration of formal diplomatic ties with the Government of Syria.

Thus, any newly established government must chart a middle path that will satisfy Western governments and Gulf states (on which Lebanon relies for economic support), Hezbollah (which has the ability to destabilize Lebanon with its continued military superiority),[2]The most notable instance in which Hezbollah took military action in Lebanon due to government policy was in May 2008, when the Lebanese government, led by Saad Hariri, attempted to declare … Continue readingand the Lebanese protest movement (which has demonstrated its capacity to shut down much of the country through protests and general strikes, and which is broadly opposed to the existing Lebanese political establishment in general).

Consequently, the election of a new prime minister and the subsequent formation of a new Lebanese cabinet that meets the approval of all of the relevant political parties and the protest movement may extend for months. Lebanon has functioned without a government in the past — the country had a caretaker government for more than two years, between May 2014 and October 2016 — however, the economic and political issues facing the Lebanese government are greater than at any time since the Lebanese Civil War, and the time available to address these issues is running out. The divergence between parallel currency exchange rates is growing wider on a daily basis, worsening the fundamental causes of Lebanon’s economic crisis, and ominous sectarian tensions are setting in, since the majority of the Sunni community appears to be supportive of the protest movement, while the majority of the ‘counter-protest’ movement is driven by Shiite supporters of Hezbollah and the Amal Movement.[3]Sectarian tensions most notably spilled over on December 17, when a group of Shiite supporters of Amal and Hezbollah stormed Downtown Beirut and its vicinity. These counter-protesters burnt vehicles … Continue reading “Lebanon is on the brink” is an overused journalistic cliche. In this case it is also true.

Economic Impact: Capital, Trade, and Remittances

The effects of Lebanon’s economic crisis are rippling across the border into Syria, as the crisis undermines the pillars of Syria’s economic reliance on Lebanon. Throughout the conflict, the Syrian economy has relied on Lebanon in four critical ways: as a financial hub for Syrian capital; as an import market for economic inputs such as fuel, industrial gas, and iron; as an export market for Syrian-produced goods; and as a source of remittances from Syrian workers residing in Lebanon. As the economic crisis in Lebanon continues to unfold, these four key channels have been — and will continue to be — severely altered.

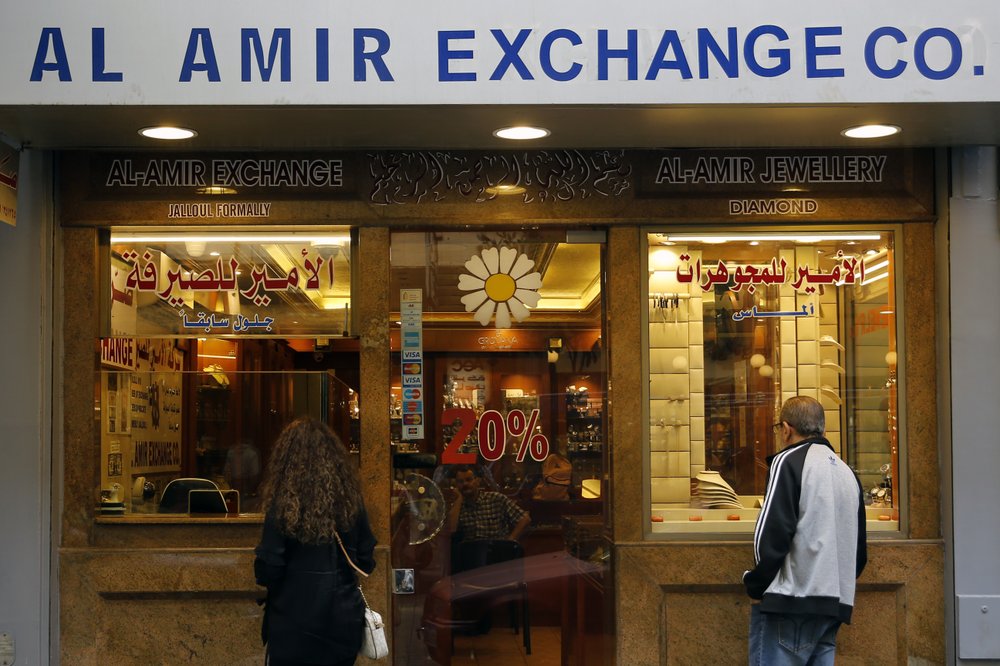

Lebanon faces numerous critical economic issues, to include a significant real estate bubble, high levels of unemployment, severe income inequality, and a lack of productive economic sectors. Ultimately, however, the largest single factor in the current Lebanese economic crisis is the rapid devaluation of the LBP. Since Prime Minister Saad Hariri declared Lebanon to be in a state of economic emergency in early September, an acute shortage of USD in Lebanon has prompted a surging demand for USD in the country’s informal exchange market. In turn, this has fueled a vicious cycle resulting in a significant divergence between the market exchange rate for USD (in every meaningful sense, now the ‘real’ value of the LBP) and the official pegged exchange rate of 1,515 LBP/USD; as of December 17, Lebanese currency exchanges sell at rates of 1,900-2,200 LBP/USD.

As a result of the rapid devaluation of the LBP, Lebanese banks have intermittently closed their doors since the start of the Lebanese crisis, for fear of devastating bank runs by depositors.[4]It is estimated that as much as 800 million USD left the country between 15 October and 7 November, when much of the banking system was officially shut down. In an attempt to prevent further capital flight, the Association of Banks in Lebanon (ABL) announced a set of universal banking restrictions in mid-November, which severely restricted account holders’ ability to withdraw USD. These capital controls have since extended to LBP withdrawals as well; the amount of LBP that can be withdrawn from individual accounts per week is curtailed by many banks.[5]In general, individual accounts are limited to withdrawals of 300 USD per month, and 1,500,000 LBP per month.While these measures are supposedly temporary, local sources with close ties to the Lebanese banking sector indicate that the weekly ceiling for withdrawals — for both USD and LBP — are likely to steadily decrease. Naturally, the wide divergence between the official LBP/USD rate and the black market rate has also increasingly caused foreign banks to refuse to accept money transfers from Lebanese banks. Essentially, depositors in Lebanese banks have for all intents and purposes had their accounts ‘frozen’; the amount of money that can be withdrawn is limited, international transfers are becoming extremely difficult, and the currency is increasingly not accepted outside of Lebanon.

Syrian Capital, Controlled

Lebanon and Syria have sustained close financial and commercial ties for decades; indeed, many Syrian mercantile families played a key role in the creation of some of Beirut’s most influential banks.[6]For example, the Azhari family, at BLOM Bank, or the Obegi family, at Banque Bemo. The Lebanese banking sector was considered a financial hub for Syrian capital even before the conflict, as the Syrian business community took advantage of the high interest rates offered by Lebanese banks following the Lebanese Civil War and used Lebanese banks as a means of conducting foreign economic transactions. The start of the Syrian conflict, in 2011, only increased the volume of Syrian deposits flowing into Lebanon, as Syrian businessmen attempted both to avoid restrictive international sanctions and to withdraw their capital from the increasingly volatile Syrian economy. Syrian companies and businesspeople have thus come to critically rely on Lebanon’s banking sector as their primary entry point to global markets and foreign capital. Naturally, the close financial interlinkages between Syria and Lebanon mean that the collapsing Lebanese banking sector has frozen the Syrian business community’s ability to store and access capital, not to mention transfer money internationally.

The increasing restrictions on withdrawals and foreign transactions, and the possibility of an outright economic collapse in Lebanon, is severely threatening the Lebanese deposits of Syrian importers, businessmen, and traders. This has dramatically affected the economic activity of Syrian shell companies in Lebanon and the businesses inside Syria that have relied heavily on the Lebanese banking system to access foreign capital and conduct foreign transactions. Moreover, according to a recent report, approximately 80 percent of upper- and middle-class Syrian families that hold capital outside of Syria have made their deposits in Lebanese banks. Syrians remain at the top of the list of foreign real estate investors in Lebanon, and, according to the Investment Development Authority of Lebanon (IDAL), Syrian investors hold 13 percent of total real estate acquisitions in Lebanon. It is estimated that around 30 billion USD in Syrian deposits are currently held by the Lebanese banking system,[7]Reportedly constituting almost a fifth of all deposits in Lebanon.20 billion USD of which is reported to have entered the country after 2011. The bulk of this capital is now effectively frozen within the Lebanese banking sector.

Unable to access deposits in Lebanon, many Syrian importers, and traders have been hit as hard as their Lebanese counterparts by the unfolding economic crisis in Lebanon, while simultaneously facing the parallel (and related) collapse of Syria’s economy. The USD shortage and knock-on weakness in local currency is driving inflation in both countries, and both local currencies are currently in freefall. Since the beginning of the Syria conflict, the SYP has suffered from a rapid decline in value, from a market exchange rate of ~47 SYP/USD in 2011 to 635 SYP/USD in August 2019. However, since the start of the Lebanese economic crisis, the SYP has deteriorated even more rapidly; it is now at an all-time low of ~850-900 SYP/USD.[8]For an overview of the rate for USD in the Syrian Forex Market from 2011 to 2019, see: https://www.syria-report.com/library/economic-data/rate-us-dollar-syrian-forex-market-2011-19.

Thus, while the ultimate cause of the SYP’s decline is undoubtedly the structural weakness of the Syrian economy itself, economists and Syria analysts point to Lebanon’s economic crisis as one of the strongest explanatory factors for the latest slump (Syria Update 13-19 November). Syria’s particular susceptibility to USD shortages in Lebanon is due primarily to Syria’s own depleted reserves, which have been used to sustain a growing import-export imbalance. For this reason, according to local sources, many Syrian importers and traders have increasingly become indebted in Syria and forced to acquire USD at unfavorable exchange rates from Syria’s depleted USD reserves, putting additional downward pressure on the SYP.

Import Impediments

Naturally the capital controls in Lebanese banks, compounded (and caused) by inflation in both Syria and Lebanon, have curtailed the ability of Syrian and Lebanese businessmen to import goods. Considering that trade between Syria and Lebanon has historically functioned as a key pillar of both countries’ economies, the unfolding economic crisis in Lebanon is poised to dramatically alter trade dynamics — both formal and informal — between Lebanon and Syria.

Since September, many Lebanese and Syrian importers have been unable to pay international producers due to an inability to make foreign transactions, which has been exacerbated by the discrepancy between the official and unofficial USD/LBP exchange rate. Necessary clearance and customs expenses at the Port of Beirut have also become prohibitive, due to the inability of many import businesses to access hard currency. Importers are reportedly choosing to send back cargo arriving at the Port of Beirut without even unloading their shipments, since traders are unable to sell imported products in the Lebanese or Syrian markets due to the increase in prices required to cover costs, let alone sustain a profit.[9]Indeed, according to one local source, many private companies have been left with no option but to pay additional shipping fees to cover the return of incoming vessels to the country of export, … Continue readingIn early October, Lebanese authorities created new financial instruments and trade mechanisms to support the import of critical staple goods, such as wheat, medicine, and fuel; however, shortages and price hikes are likely to increase in Lebanon as the crisis develops.

Syria has already begun to feel the effects of the decrease in imports from Lebanon; the most critical impact thus far has been in fuel and gas imports. Syria has suffered severe fuel and gas shortages throughout the conflict, which have only grown worse throughout 2018-2019. Fuel and gas imports from Lebanon, through both formal channels and smuggling networks, have been an important part of the Syrian economy. In April 2019, it was estimated that Syria imported 1 million liters of gasoline from Lebanon per day, covering approximately 25 percent of daily consumption. In addition, about 100,000 liters of gasoline were estimated to have been smuggled into Syria daily since at least mid-2019, primarily through the Qalamoun region. Similarly, industrial gas and iron imported from Lebanon were both important inputs for what remains of the Syrian industrial sector. While cross-border smuggling of fuel and industrial gas from Lebanon to Syria is likely to continue, the quantities that can be smuggled overland are likely far from adequate to meet the needs of the Syrian population.

With no signs of improvement in the Lebanese economy in the near future, Syrian businesses reliant on Lebanese imports are expected to see the existing production and import challenges greatly exacerbated. Local sources note that many Syrian factories, especially in Damascus, have already halted production due to gas shortages. As winter sets in, the lack of access to fuel imports from Lebanon will only become increasingly severe. During winter 2018-2019, fuel shortages caused a significant decline in Syrian living standards nationwide and led to widespread public unrest.[10]Syrians rely heavily on fuel to cook and to heat homes.In light of Syria’s dire fuel shortages, and Lebanon’s inability to export fuel due to its own shortages, it is likely that conditions in Syria this winter will be even worse than last year. While Iran’s reactivation of a 3 billion USD credit line to Syria to purchase fuel may provide some support to meet shortfalls during the fuel-intensive winter months, it is doubtful that Iran — embattled by its own domestic uprising and increasingly isolated abroad — will be capable of guaranteeing that all of Syria’s fuel needs are met (Syria Update 27 November-3 December). Essentially, the Lebanese crisis has made even more complicated the import of goods into Syria, with multiple knock-on effects for both Syrian industries and the Syrian population as a whole. How import needs will be met remains unclear.

Export Changes

Conversely, while Syria’s ability to access international imports is dramatically restricted by the Lebanese crisis, Syrian exports to Lebanon may actually increase. Even now, Lebanon remains Syria’s single largest export market. In light of Lebanon’s unfolding economic crisis, and the country’s inability to sustain international imports on a large scale, Syria’s role in exporting goods to Lebanon is bound to become increasingly relevant, as Syrian businesses export Syrian goods to fill the increasing demand in Lebanon. On the one hand, this may be a positive development for Syrian businesses and Syrian producers; on the other, increased Syrian exports to Lebanon — both formal and informal — may lead to further shortages within Syria.

The prices of imported foodstuffs, and staple goods, are rapidly rising in Lebanon. While Lebanon is an agricultural producer, international imports reportedly cover approximately 80 percent of Lebanon’s food needs. While Lebanese authorities reportedly intend to explore mechanisms to boost the Lebanese agricultural sector in light of potential food shortages, it is unlikely that any agricultural support will have a meaningful impact in the short or even medium term. To that end, Syrian exports to Lebanon and cross-border smuggling of staple goods are likely to increase significantly.

In fact, the effects of increased cross-border smuggling have already begun to manifest in Syria’s border areas. In late November, supplies of basic commodities — including sugar, margarine, detergents, and other items — became scarce in markets in Lattakia and Tartous. The shortages were reportedly caused by an outflow of goods to Lebanon via a newly established cross-border smuggling operation, reportedly enabled by a smuggling network involving Government of Syria security officials, local producers, and Hezbollah intermediaries in Syria (Syria Update 20-26 November). According to local sources, the Lebanese market has already begun to prepare for further imports. For example, in November, two grocery stores dealing exclusively in Syrian and Iranian goods opened in the southern suburbs of Beirut — almost immediately following the imposition of capital controls. While these shops’ shelves remain only partially filled, their establishment is an indicator that at least some of the Lebanese importers expect to see both formal and informal exports from Syria and Iran increase.

The ability of Syrian producers to take advantage of a sustainable export market in Lebanon will likely vary. Some Syrian producers may yet benefit from increased demand in Lebanon; key sectors where Syria’s historical capacities meet Lebanon’s expected needs, such as agricultural production and medicine, will be particularly well positioned to capitalize on Lebanon’s current import challenges. Looking forward, so long as Lebanon’s importers remain incapable of directly accessing foreign markets, Syria’s exporters — and smugglers — will rise to meet that demand, potentially increasing shortages in Syria.

Remittances: Syria’s Economic Lifeline

Refugee and expatriate remittances are a key component of the Syrian economy, and they constitute a vital lifeline for Syria’s conflict-affected populations. In 2018, an estimated 150 million USD of remittances entered the country on a monthly basis. In fact, remittances have long accounted for a significant share of Syria’s national revenue — from 2 percent in 2011 to 19 percent in 2016 — with Lebanon constituting the second largest source of total remittances: 17 percent in 2015.[11]It is important to note that obtaining reliable statistical data on remittances is difficult: the large number of remittance transactions and the multitude of channels, including formal (such as … Continue readingRemittances are one of Syria’s most significant sources of foreign currency infusions and are critical to sustain the livelihoods of many living inside Syria. According to the Overseas Development Institute (ODI), recipients of remittances in Syria primarily spend this money on food, shelter, and healthcare, allowing them to avoid negative coping strategies.[12]https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/12638.pdf Remittances are primarily spent in the private sector, helping to maintain local markets for basic commodities and injecting money into the local economy. Thus, as remittances from Lebanon dwindle, the Syrian economy (and the populations dependant on those remittances) will be badly affected.

The unfolding economic crisis in Lebanon has already significantly affected the ability of the estimated 1.5 million Syrians residing in Lebanon to transfer remittances to Syria. The impact of Lebanon’s economic crisis on Syrian remittances is two-fold: First, increased capital controls have severely impacted formal transfer channels, as almost all of Lebanon’s transfer agencies are now only accepting payments in USD; as such, individuals wishing to send back remittances are now forced to exchange their salaries in LBP to USD before transactions can be completed, losing a significant portion of the initial deposit in the process.[13]Remittance payments lose additional value when they are converted into SYP; thus, Syrians transferring money from Lebanon to Syria lose part of their remittance value twice over.

Second, the economic crisis in Lebanon has significantly affected the country’s labour force and, with it, the incomes of the hundreds of thousands of Syrian workers who regularly send remittances to their relatives in Syria.[14]Prior to the Syria conflict, it is estimated that 300,000 Syrians were working in Lebanon, most of whom were employed in construction, agriculture, and the service industry.While reliable data on the current number of Syrian workers in Lebanon remains unavailable, it is widely believed that a significant percentage of the estimated 1.5 million Syrians living in Lebanon participate in the labour force to some degree, either under the kafala system[15]The kafala sponsorship system is a Lebanese work permit system that covers foreign workers in Lebanon. According to the system, a Syrian national must secure a ‘pledge of responsibility’ from a … Continue readingor illegally. According to a survey published by Infopro Research in November 2019, 10 percent of Lebanese businesses have ceased operations since the outbreak of the protests in mid-October, one-third of Lebanese businesses have reduced the salaries of their employees, and approximately 160,000 Lebanese have lost their jobs entirely. As economic activity dramatically slows down, and the Lebanese labour force continues to be severely hit by the economic crisis, Syrian workers in Lebanon will almost certainly be affected as unemployed Lebanese turn to ‘undesirable’ labour that had previously been filled by Syrians. While the setbacks to the Lebanese economy will be felt across all sectors, real estate will likely be acutely affected; this will negatively impact Syrian workers, who constitute approximately 70 to 80 percent of all construction workers in the country.

Syrian Refugees in Lebanon: Logistical Challenges, Social Tensions, and Returns

Lebanon’s economic crisis and current political deadlock has naturally exacerbated the challenges facing the Syrian refugee community in Lebanon as well as the programmatic interventions aimed at meeting their needs.[16]Approximately 1.5 million Syria refugees are currently living in Lebanon, of whom 961,113 are registered with UNHCR. Many of the challenges that Syrian refugees in Lebanon faced prior to the current crisis stemmed from Lebanon’s poor infrastructure, services, and economic situation. In light of the unfolding economic crisis and political turmoil, response actors operating in Lebanon will certainly face new operational and programmatic obstacles to addressing Syrian refugees’ needs.

Additionally, tensions between Syrian refugees and Lebanese citizens are likely to mount as the economy deteriorates. Every political party currently represented in the Lebanese cabinet is unified regarding the necessity of the return of Syrian refugees to Syria; disagreements center on the means by which this return should be facilitated (via negotiations with UNHCR or directly with the Government of Syria). Anti-refugee political and social rhetoric is widespread and, while the Government of Lebanon still lacks comprehensive refugee policy, local authorities[17]Given the lack of a national policy, municipalities and ministries have sought to adopt decentralized policies that aim to affect refugees’ residency status, employment opportunities, housing … Continue reading and individual ministries have a relatively wide mandate to pursue anti-refugee campaigns.[18]The latest of these policies was the Ministry of Labor campaign against foreign labor launched in July 2019. Although the campaign was ostensibly carried out under the pretext of regulatory … Continue reading Given the current political deadlock, Lebanon is unlikely to fundamentally change policy, and the decision to deport Syrian refugees in large numbers will likely never be taken; however, pre-existing social, legal[19]The Government of Lebanon has imposed significant restrictions on refugees to obtain work permits and legal residencies. As a result, many refugees who are incapable of meeting the stringent … Continue reading, and economic pressures facing Syrian refugees will remain and likely worsen. As such, the potential for increased anti–Syrian refugee sentiment, coupled with a deteriorating economy, will likely affect the pace of return for at least some Syrian refugees.

Logistical and Programming Issues

The current political and economic turmoil that Lebanon is facing entails serious operational challenges for programmatic interventions to meet the needs of Syrian refugees in Lebanon. These challenges include access to host communities and beneficiaries — complications with regards to cash programming, community acceptance, and local authority support are particularly noteworthy.

Following the outbreak of demonstrations across Lebanon, mobility and transportation throughout the country were intermittently restricted, with key highways sporadically closed; access to informal refugee camps, host communities, and project sites was temporarily impeded, forcing many response staff to work remotely and suspend programming. These mobility and transportation restrictions have decreased, however, and programming has largely resumed. But confrontation between protesters and supporters of political parties or state security and military agents are becoming more frequent, and road closures are likely to continue to be a fact of life in Lebanon for the duration of the crisis. Furthermore, incidents of violence and unrest remain a distinct possibility and would naturally impinge upon the operational capacity of response actors and threaten the safety of their staff.

Moreover, Lebanon-based response actors, including INGOs and the UN, will be affected by the Lebanese economic crisis. Restrictions on money transfers and recurrent bank closures have introduced new logistical and financial challenges for Lebanon-based agencies. Organizations have encountered difficulties conducting money transfers within Lebanon and making salary payments. These challenges are expected to especially impact the efficacy of cash-based programs, due to the devaluation of the LBP and the decreasing availability of USD. Notably, in October alone, WFP has assisted a total of 730,717 beneficiaries through cash-based transfer modalities that amount to 23.5 million USD.[20]The people assisted were: Syrian refugees, Palestinian refugees, refugees of other nationalities, vulnerable Lebanese through the National Poverty Targeting Programme (NPTP), Syrian and Lebanese … Continue reading As food prices increase, programmers will also need to constantly reassess the value and cost of in-kind food baskets for distribution.[21]According to the WFP, the price of the Survival and Minimum Expenditure Basket (SMBE) increased 8 percent between 16-31 October. But local NGO sources indicated that humanitarian organizations are … Continue reading Given Lebanon’s reliance on imports, the scope of the challenges facing these actors is likely to grow, placing future procurement in jeopardy.

Finally, NGOs are expected to face challenges partnering with local authorities and securing community acceptance. According to NGO sources, municipalities have recently threatened their access if they do not prioritize servicing and supporting the Lebanese population. These concerns are not unfounded — as the crisis continues, the Lebanese population will certainly become more impoverished — and municipalities are likely to further pressure NGOs and limit their operational space. Given the absence of an overall state refugee policy, the endorsement of local governance bodies and the acceptance of local communities is indispensable for the continuation of NGO programming. As such, the destabilization of NGO partnerships with these bodies could potentially threaten the possibility of future programming in certain localities and undermine NGOs’ abilities to meet the needs of host communities and refugees.

Relations Between Syrians and Lebanese

The Government of Lebanon has for years focused its political rhetoric on Syrian refugees as a primary cause of Lebanon’s economic hardship, which has naturally contributed to growing tensions between the Lebanese population and Syrian refugees. The protest movement in Lebanon has thus far concentrated on the political elite and business class, and anti-refugee rhetoric has been largely — if not entirely — absent. The danger remains, however, that Syrian refugees will become a focal point amid growing civil unrest and increasingly dire economic conditions. Considering this context, there are two primary considerations when assessing the likelihood of tensions between Syrians and Lebanese in Lebanon: first, the perception that the international community is prioritizing aid to Syrians over Lebanese; and second, the perception that Syrian workers are displacing Lebanese workers from the tightening labor market.

In spite of the instability of the current economic landscape, international humanitarian actors in the Lebanon-based response appear to have reached a consensus — for now — to continue cash programming to Syrian refugees inside Lebanon, despite potential social and macroeconomic consequences. While both Syrians and Lebanese are challenged by withdrawal restrictions and market conditions, programming options are available to ensure that beneficiaries can continue to receive cash or support through preferred vendors. As host communities face the prospect of new withdrawal restrictions, Syrian refugees’ continued access to cash and donor support may inflame existing tensions. Already, local and NGO sources have reported increasing tensions, to include raids on informal camps, burning of tents, plans to demolish concrete structures erected by refugees, and disputes between Lebanese Civil Defense members and refugees. Moreover, local NGO sources report that a group of Lebanese individuals stormed INGO offices in Aarsal and Zahle in early November, motivated by discontent over staff ‘disengagement’ from the ongoing Lebanese protest movement and the international community’s perceived prioritization of Syrian beneficiaries at the expense of Lebanese hosts.

In this context, it is consequential that most Syrian refugee families are reliant on a single income earner — frequently employed in manual labor, which Lebanese have generally eschewed. Until now, this has, to a large degree, counterweighted the perception that Syrians are taking employment opportunities away from Lebanese. However, this calculus is likely to change as the economic crisis exacerbates already high unemployment rates and as livelihood opportunities heretofore favored by many Lebanese become increasingly scarce. Large segments of the Lebanese workforce will likely be increasingly willing to take on unskilled and low-wage labour, heightening the sense of direct labor competition between host and refugee populations.

Drivers (and Impediments) to Return

Considering the political upheaval and deepening economic hardships confronting both Syrians and Lebanese, as well as the new challenges facing the Syria refugee response inside Lebanon, an increase in the number of refugee returns to Syria must be considered a distinct possibility as the crisis develops. However, while multiple push factors are present, as a result of the deteriorating economy and the potential for increased hostility from the host population, it is important to bear in mind the differences among Syrian populations inside Lebanon. Indeed, the Syrian refugee population in Lebanon is far from monolithic. Important class distinctions exist, and there are many Syrians who are entirely unable to return to Syria due to Government of Syria policy.

Anti-refugee rhetoric in Lebanon has been a consistent feature of Lebanese political discourse since the start of the conflict.[22]Notably, in June 2018, then–Foreign Minister Gibran Bassil ordered a freeze of residency permits for UNHCR staff and threatened to take further measures, accusing UNHCR of impeding the return of … Continue reading To date, however, the Lebanese state has not initiated a large-scale return of refugees and is unlikely to take overt measures to that effect, or to announce a national refugee policy. Instead, returns are likely to continue in the same manner in which they have taken place throughout the latter stages of the displacement crisis: through small-scale returns coordinated by various Lebanese security forces. The pace of these returns has increased since the beginning of 2019 and is likely to continue to do so.

The most recently reported return occurred at the beginning of December, when a large number of Syrian refugees — reportedly as many as 1,500 — returned to Syria from various areas in Lebanon, to include the Bekaa Valley, Tripoli, Nabatieh, and Beirut (Bourj Hammoud, specifically), as a result of coordination efforts between Lebanese security authorities and the Government of Syria (Syria Update 4-10 December). According to local NGO sources, as many as 3,000 Syrian refugees returned through the Masnaa border crossing in December.

However, Lebanon’s declining economic conditions and rising market costs should naturally be seen as the major push factor for return. Syrian refugees residing in informal settlements in the Bekaa Valley and other rural areas are by far the most vulnerable to the increasingly dire economic situation in Lebanon. Thus far, returns have largely been reported as voluntary (although involuntary returns have been documented); however, the motivations behind Syrian refugees’ decision to return are difficult to discern, and reports on return numbers are both highly politicized and subject to significant variation, depending on the source.

However, it is important to note one major issue: although some Syrian refugees might consider returning to Syria due to declining economic conditions and social tensions in Lebanon, whether they are allowed to return is another matter. The Government of Syria has strictly monitored returns. Returnees must pass in-depth security checks and reconciliation procedures as a matter of policy, and many individuals are reportedly prevented from returning and ‘reconciling’. Additionally, most military-aged males are subject to conscription by the Government of Syria — which is viewed as a death sentence by many refugees — unless they pay exemption fees of up to 8,000 USD. Thus, while there are multiple push factors for return, many refugees will, in practice, be unable to return to Syria as a matter of Syrian state policy. Essentially, these individuals are ‘trapped’ in Lebanon for the foreseeable future. These refugees, like the vast majority of the Lebanese population, will be forced to negotiate a landscape in which deep instability is now the status quo.

References[+]

| ↑1 | It is important to note that although this geopolitical division among Lebanese political parties has been a relatively fixed feature of Lebanese politics, several political parties regularly change their geopolitical orientation. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The most notable instance in which Hezbollah took military action in Lebanon due to government policy was in May 2008, when the Lebanese government, led by Saad Hariri, attempted to declare Hezbollah’s telecommunications network illegal. Viewing their telecommunications network as an essential component of their ability to militarily resist Israel, Hezbollah combatants took control of several neighborhoods of Beirut, in a series of clashes that lasted for nearly a week. The government reversed its decision within the month. |

| ↑3 | Sectarian tensions most notably spilled over on December 17, when a group of Shiite supporters of Amal and Hezbollah stormed Downtown Beirut and its vicinity. These counter-protesters burnt vehicles and clashed with security forces, after a Sunni individual released a video criticizing Shiite politicians and religious figures; the individual claimed to be from Tripoli, a predominantly Sunni city in northern Lebanon. |

| ↑4 | It is estimated that as much as 800 million USD left the country between 15 October and 7 November, when much of the banking system was officially shut down. |

| ↑5 | In general, individual accounts are limited to withdrawals of 300 USD per month, and 1,500,000 LBP per month. |

| ↑6 | For example, the Azhari family, at BLOM Bank, or the Obegi family, at Banque Bemo. |

| ↑7 | Reportedly constituting almost a fifth of all deposits in Lebanon. |

| ↑8 | For an overview of the rate for USD in the Syrian Forex Market from 2011 to 2019, see: https://www.syria-report.com/library/economic-data/rate-us-dollar-syrian-forex-market-2011-19. |

| ↑9 | Indeed, according to one local source, many private companies have been left with no option but to pay additional shipping fees to cover the return of incoming vessels to the country of export, carrying the goods that had been intended for import. These businesses are thus doubly penalized: they are essentially forced to pay fees to return goods that they are unable to sell. |

| ↑10 | Syrians rely heavily on fuel to cook and to heat homes. |

| ↑11 | It is important to note that obtaining reliable statistical data on remittances is difficult: the large number of remittance transactions and the multitude of channels, including formal (such as electronic wire) or informal (such as cash across borders), pose challenges to the compilation of comprehensive statistics. |

| ↑12 | https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/12638.pdf |

| ↑13 | Remittance payments lose additional value when they are converted into SYP; thus, Syrians transferring money from Lebanon to Syria lose part of their remittance value twice over. |

| ↑14 | Prior to the Syria conflict, it is estimated that 300,000 Syrians were working in Lebanon, most of whom were employed in construction, agriculture, and the service industry. |

| ↑15 | The kafala sponsorship system is a Lebanese work permit system that covers foreign workers in Lebanon. According to the system, a Syrian national must secure a ‘pledge of responsibility’ from a Lebanese national in order to secure residency and a work permit. Though the sponsorship system does not exclusively require an employment relationship between sponsor and applicant, Lebanese General Security regularly rejects other forms of sponsorship, such as sponsorships of personal acquaintances, requesting work-related agreements instead. As economic conditions worsen, there is the persistent risk that sponsorships will become more difficult to obtain, or even that existing agreements might be revoked. |

| ↑16 | Approximately 1.5 million Syria refugees are currently living in Lebanon, of whom 961,113 are registered with UNHCR. |

| ↑17 | Given the lack of a national policy, municipalities and ministries have sought to adopt decentralized policies that aim to affect refugees’ residency status, employment opportunities, housing access, and access to health and education services. Many Lebanese municipalities regularly conduct surveillance on Syrian refugee communities, set curfews on refugees, and force the closure of small businesses run by refugees. |

| ↑18 | The latest of these policies was the Ministry of Labor campaign against foreign labor launched in July 2019. Although the campaign was ostensibly carried out under the pretext of regulatory enforcement, it nonetheless was symptomatic of the rise of overt anti–Syrian refugee rhetoric. |

| ↑19 | The Government of Lebanon has imposed significant restrictions on refugees to obtain work permits and legal residencies. As a result, many refugees who are incapable of meeting the stringent requirements are denied access to services, subjected to security threats and deportation, and left reliant on international aid. |

| ↑20 | The people assisted were: Syrian refugees, Palestinian refugees, refugees of other nationalities, vulnerable Lebanese through the National Poverty Targeting Programme (NPTP), Syrian and Lebanese through livelihoods activities, and children through the school food program. |

| ↑21 | According to the WFP, the price of the Survival and Minimum Expenditure Basket (SMBE) increased 8 percent between 16-31 October. But local NGO sources indicated that humanitarian organizations are not currently considering a monthly (rather than annual, as is current practice) revision of the SMBE pricehttps://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP0000110413/download/ |

| ↑22 | Notably, in June 2018, then–Foreign Minister Gibran Bassil ordered a freeze of residency permits for UNHCR staff and threatened to take further measures, accusing UNHCR of impeding the return of Syrian refugees to Syria. https://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Lebanon-News/2018/Jun-08/452537-bassil-says-steps-to-be-taken-against-unhcr.ashx |