Syria Update

6 January 2020

Download PDF Version

Table Of Contents

Iran’s ‘Living Martyr’ Soleimani Killed: U.S. Strikes

Match in Tinderbox Region

In Depth Analysis

In an event that will profoundly shape the dynamics of war and peace across the Middle East, in the early hours of 3 January, U.S. forces carried out a lethal drone strike outside Baghdad International Airport, killing Qasim Soleimani, the commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’s Quds Force and a revered figure who has served as the master architect of Iran’s external military engagement, including its efforts to militarily support Bashar Al-Assad in Syria. The strike reportedly killed seven others, including Abu Mahdi Al-Muhandis, the head of the Iraqi Kitaeb Hezbollah militia, which is supported by Iran. The profound significance of Soleimani’s killing and its potential ramifications are difficult to overstate. What can be said with certainty is that the event constitutes a grievous escalation in a chain of increasingly tense and lethal confrontations between U.S. forces and Iran-affiliated groups; in the immediate term, the killing invites a forceful response from Iran, and it opens the door to potentially catastrophic tit-for-tat responses in Iraq and regionally.

The Pentagon has justified the strike on the grounds that Soleimani “was actively developing plans to attack American diplomats and service members in Iraq and throughout the region.” Nonetheless, Soleimani was targeted at least in part as a response to the humiliating siege of the U.S. embassy in Baghdad by members of Kitaeb Hezbollah, and the power play over Iraq that it presaged. On 31 December, demonstrators stormed Baghdad’s Green Zone and breached the outer walls of the U.S. embassy complex, which they occupied until receiving promises that the Iraqi Parliament would reassess the terms of Iraq’s longstanding security cooperation with U.S. forces. On 2 January, U.S. Secretary of Defense Mark Esper stated that in the wake of the embassy incident, “the game has changed.” The killing of Soleimani — who has long been in American crosshairs — confirms this, and it raises the stakes even higher.

The killing will have myriad consequences inside Iran. The sudden escalation in U.S.-Iran tensions will empower Iran’s domestic hardliners and hawks (see Syria Update 9-15 May 2019). Contrary to the assertions of some Western pundits, Soleimani was one of the most popular national figures in Iran; although some in Iran will quietly celebrate Soleimani’s demise, by and large the Iranian public is likely to rally around the flag in the wake of his death, and the massive popular mobilizations that have mounted an unprecedented challenge to Iran’s central authorities in recent months will likely abate. Furthermore, Soleimani’s death introduces unwelcome ambiguity to Iran’s regional agenda. As a Kissinger-like grand strategist, a singularly focused military commander, and the object of pious devotion as a ‘living martyr’, Soleimani was a keystone of Iran’s state apparatus, second in stature only to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. For two decades, Soleimani has spearheaded the regional military cooperation — against Israel as well as ISIS — that has won Iran a vast arc of influence through partners including Hamas, Hezbollah, and a multitude of local militias in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen. Iran’s relationships with (and its command and control over) these actors will now be subject to worrisome changes. Most concerning, however, is the fact that Soleimani’s pragmatic and strategic outlook had imparted a degree of predictability to Iran’s military activity abroad. In effect, Soleimani was viewed as the most important breakwater against the waves of the increasingly aggressive American pressure campaign. Notwithstanding Iran’s vows to continue to prosecute its regional agenda without change, the relative predictability lent by Soleimani is no longer a given, as the commander’s former deputy and appointed successor, Ismail Ghaani, steps up.

Looking ahead, an in-kind response by Iran and its regional allies is now likely unavoidable; what remains to be seen is how and where such a response will occur. Khamenei has vowed “severe revenge” will follow. In Lebanon, Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah has also pledged “revenge” for the assassination, vowing that once “the coffins of American soldiers and officers begin returning home, Trump and his administration will realize they have lost the region,” although notably, Nasrallah stated that America civilians would not be targeted.

Myriad responses by Iranian proxy forces targeting U.S. interests and American allies are plausible. Viable targets are distressingly vulnerable, to include: commercial oil tankers in the Persian Gulf, oil and gas infrastructure in the GCC, diplomatic facilities, global cyber infrastructure, and U.S. military forces stationed in sprawling Gulf outposts. The severest direct consequences, however, will likely be felt in Iraq, which is now primed to be the primary theater of further escalation. Popular momentum that Iran gained as a result of the U.S. embassy siege has rapidly crystalized in the wake of Soleimani’s assassination. Iran is likely to wield this momentum in a bid to bring Iraq into its own orbit, and on 5 January, the Iraqi Parliament took the first procedural steps to expel U.S. forces from the country. The U.S., too, has begun to pour additional manpower into the region to combat Iranian interests in Iraq, setting up the likelihood of more costly confrontations and further escalation. Already there are signs that various Iraqi factions will seek to exploit these conditions to gain more power on the national stage. The clearest (and perhaps only) beneficiary of the further disintegration that is now distinctly possible in Iraq, however, will be ISIS. ISIS cells have continued to carry out small-scale and ad-hoc attacks in much of western Iraq; by distracting from the battle to suppress these increasingly bold cells and shatter their fractured networks, the U.S.-Iran confrontation will create the conditions that could fuel a long-feared ISIS resurgence that will spread into Syria and potentially beyond.

In Syria, reaction to Soleimani’s death has broken along ideological lines. State media has naturally condemned the killing of a military commander whose regional intervention has been crucial to the Government of Syria’s survival. For this very reason, the Syrian opposition has largely celebrated the strike. Ultimately, Soleimani’s death should focus attention on the fact that conflict in the Middle East is increasingly becoming internationalized, as regional powers assert themselves, and spillover effects are becoming difficult or impossible to contain (see point No. 8 below). Should the U.S. succeed in its improbable efforts to de-escalate tensions with Iran now that the hounds of war have been loosed, aftershocks will nonetheless continue to be felt, including in Syria. ISIS cells active in Syria’s eastern hinterlands will surely be emboldened — and may well seize the opportunity to target international coalition forces and the SDF. Iran-backed militias located throughout Syria will almost certainly be marshaled as regional confrontation unfolds. As we wrote in response to a spike in U.S.-Iran tensions in May: “War is the unfolding of miscalculations.” This dictum is more relevant now than ever.

Whole of Syria Review

1. Twice vetoed, cross-border resolution set to expire 10 January

New York City: On 20 December, the UN Security Council failed to extend Resolution 2165 (2014), the touchstone resolution of the Syria crisis response, which enabled cross-border aid delivery through four border crossings, with Turkey, Iraq, and Jordan (see Syria Update 11-17 December 2019). Absent modification for the first time since it was enacted in 2014, the serially renewed resolution will expire on 10 January. Notably, the Security Council voted on two modified draft resolutions: one proposed by Germany, Kuwait, and Belgium, and the other drafted by Russia. The Russian proposal — vetoed by France, the United Kingdom, and the United States — stipulated that in place of the standard one-year renewal, the resolution would be extended by six months, to permit access through two border crossings with Turkey, while border crossings at Yaaroubiyeh (with Iraq) and Al-Ramtha (with Jordan) would be decommissioned. The counter-proposal seeking a piecemeal extension of 2165 was also shot down. Under this proposal, three border crossings — two with Turkey and one with Iraq — were to remain operational for an additional 12 months, while access via Al-Ramtha crossing was to be extended for six months, with a further conditional six-month extension to follow, unless explicitly overruled by the Security Council. Both China and Russia vetoed this proposal.

Resolution 2165: Once operational, now geopolitical

Ultimately, the competing proposals to amend 2165 reflect the disparate objectives of ostensible blocs that exist within the Syria crisis response: one led by Russia and broadly supportive of the Government of Syria, and another nominally representing the UN and Western INGOs, and advocating for an expansive vision for the cross-border response. The Russian proposal would achieve several Russian aims: closing the largely defunct Al-Ramtha crossing would deliver a message about Syria’s sovereignty, while shuttering Yaaroubiyeh would undermine SDF-held areas in northeast Syria, which remain largely dependent on medical supplies delivered by UN convoy via Yaaroubiyeh. The latter goal is also shared by Turkey, which is effectively dependent upon Russia to represent Turkish interests in the Security Council. Conversely, the competing proposal aims to preserve a capacious response architecture that Russia and the Government of Syria have long decried as an affront to Syria’s territorial integrity. Both proposals, however, would extend the mandate of the cross-border response in northwest Syria, which plays an important coordination role and has grown in capacity by 40 percent since 2018, largely in response to serial and protracted displacement in the region.

The failure of rival blocs to reach a compromise over 2165 for the first time is a worrying sign that the cross-border response will be held captive to geopolitical wrangling among Security Council members. Should the resolution expire, it is possible that cross-border aid convoys will continue, albeit under a cloud of uncertainty concerning their legality and mandate. INGO aid deliveries — which are not explicitly addressed by the resolution — will also be exposed to greater liability. As a result, the UN and the Syria response itself may be caught flat-footed until a compromise is passed — a process that may drag on for months.

2. Embattled PYD extends olive branch to Kurdish rivals

Al-Hasakeh city, Al-Hasakeh governorate: On 17 December, the Self Administration — dominated by the Democratic Union Party (PYD) — announced its willingness to reconcile with the rival Kurdish National Council (KNC/EKNS) in an attempt to unify the Kurdish political and military front in Syria. The Self Administration claims it has revoked all previously enforced restrictions on the KNC, including security restrictions on the latter’s personnel and suppression of its political activities in SDF-controlled areas. Additionally, as per the statement, the Self Administration has vowed to release political prisoners and disclose the fate of KNC-affiliated individuals among the disappeared. To date, reports over the KNC’s response to the olive branch initiative are contradictory. Unconfirmed media reports indicate that direct negotiations between the KNC and the Self Administration that took place in Al-Hasakeh city produced a tentative agreement, which purportedly stipulates the deployment of Peshmerga forces from Iraq to northeast Syria, in support of Self Administration control. However, public statements by members of the KNC denied that a final agreement had been reached, although some such accounts verified that meetings had taken place.

Building a united Kurdish front

The PYD exercises a near monopoly over the political field in the Self Administration; attempts to woo the KNC thus suggest that the Self Administration is now willing to undertake desperate measures in the face of its growing political and military isolation. As a result of the long-running and often combative rivalry with the PYD, the KINC has effectively been exiled to Erbil, yet the KNC’s closeness to Turkey — a relationship which has long been anathema to the PYD — may now provide the means of assuaging Tukish concerns in northeast Syria. Moreover, a detente with the KNC would also bolster the SDF militarily by adding to its ranks the Rojava Peshmerga, which has an almost mythic stature in northeast Syrian politics, where it is widely considered a partial solution to nearly all pressing military concerns, particularly those involving Turkey. Previous attempts to bring the Peshmerga into northeast Syria, to act as a buffer force along the Syria-Turkey border, have failed, at least in part due to intransigence on the part of the Self Administration. What distinguishes the present case, however, is that the Self Administration now faces the seemingly unavoidable prospect of painful concessions in its political negotiations with Damascus (see Syria Update 4-10 December). Building a stronger, multi-party Kurdish alliance will no doubt give Self Administration negotiators more backbone to stand up to Damascus; the military support of the formidable Rojava Peshmerga would undoubtedly do even more work in this respect.

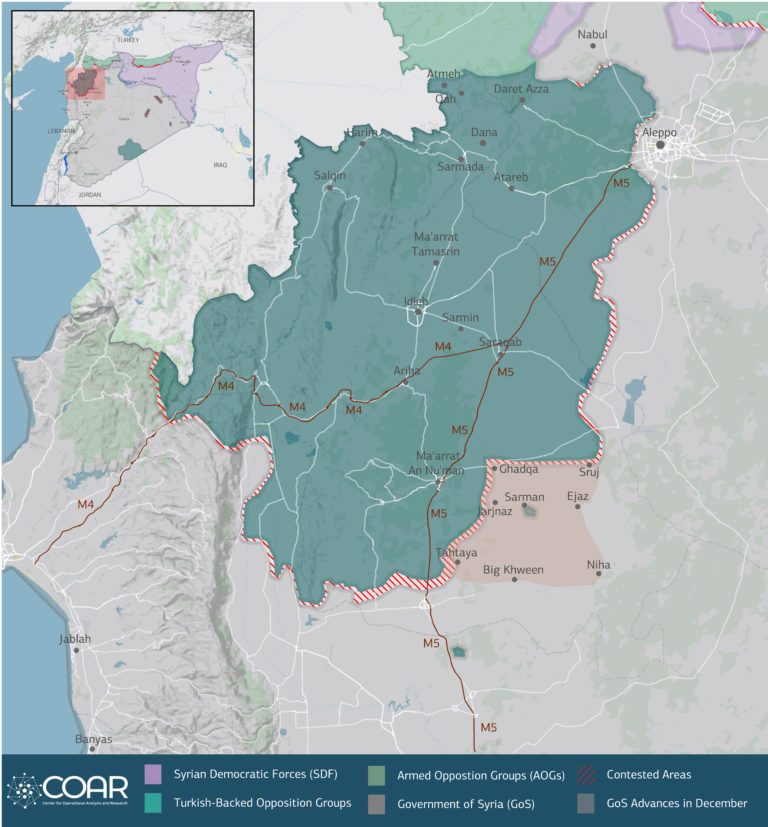

3. Government of Syria resumes ground offensive in Idleb

Jarnjaz, Idleb Governorate: On 2 January, local sources reported that intense Russian and Government of Syria bombardment of southeastern Idleb governorate had partially subsided, following weeks of heavy shelling and airstrikes, in addition to fierce clashes between opposition groups and Government forces, after the Government of Syria launched a ground offensive on 19 December. To date, the Government has captured numerous communities in southeastern Idleb, to include Jarnjaz, while a Turkish observation point at Sarman is now entirely surrounded, as frontlines recede behind it (see inset map). Echoing previous offensives, the heavy bombardment is a bid by the Syrian Government to retake territory by driving the resident and IDP populations of frontline communities deeper into opposition-held northwest Syria (see Syria Update 25-31 July 2019). Ma’arrat An-Nu’man, the most significant community now lying in the immediate line of fire, is nearly entirely depopulated, and much of the population of the surrounding countryside has likewise displaced; an estimated 284,000 individuals fled the area in December alone due to the offensive, according to UNOCHA.

Out of the frying pan, into the fire

The Government of Syria’s military strategy in northwest Syria remains consistent: brief ground assaults that punctuate long periods of intense aerial bombardment have slowly, progressively eaten away at opposition-held territory. The strategy has guaranteed the mass displacement of frontline communities. Local sources report that few of the newly displaced have found shelter in IDP camps located in relative safety along the Turkish-Syrian border, due to the size of the displacement and camp overcrowding that has been intensified by winter flooding. As a result, many of those fleeing active frontlines and targeted areas have relocated to population centers in northeast Idleb and southwest Aleppo governorates, including Idleb city and Ariha. However, even in these areas, many IDPs have been turned away by local landlords who demand three months of rent upfront. Plans are underway to expand IDP camps, but this will do nothing to address the needs of the newly (and serially) displaced. As a result of these conditions, IDPs are settling in public facilities such as mosques, banquet halls, and schools. Disconcertingly, all of these are among the structures that have been deliberately targeted in Government of Syria attempts to uproot the opposition in northwest Syria.

In the immediate term, the massive displacement poses an acute humanitarian emergency. Large gaps have arisen not only in shelter, but in food, education, healthcare and psychological support. These gaps have been aggravated by inconsistent access, harsh winter conditions, and continuing bombardment. However, the displacement is also a prelude to further intractable issues in the opposition-held northwest, where nearly 3 million people are effectively trapped in the slowly shrinking pocket of armed-opposition control. According to local sources, this population shows no sign of warming up to the prospect of reconciliation with the Government of Syria. In parallel, Turkey remains firm in its categorical refusal to admit more Syrians across its borders as refugees. Consequently, as Government of Syria–led bombardment and ground forces slowly but surely advance toward the strategic M5 highway, the displaced population is likely to be confined to an ever-receding pocket of territory.

4. Military service law amended: Serve, pay up, or forfeit assets

Damascus: On 17 December, local media sources reported that the Syrian Parliament had passed an amendment to the country’s wide-reaching military service requirement, Law 97 (2008). The amendment allows for the confiscation of assets belonging to individuals who fail to fulfill their military service obligation and who are unable to pay the $8,000 ‘offset’ that has long served as an escape clause for military-age Syrians of means, and many in the diaspora.

Breaking home ties?

Mandatory military service remains among the key deterrents to return for Syrian males of conscription age; it is naturally an underlying factor for internal displacement as well as emigration. Notably, as of 2019, the median wealth of a Syrian adult had fallen to a mere $884, by some estimates (see Syria Update 20-26 November 2019); as such, the sum levied for exemption from conscription is well beyond the reach of most Syrians. By seizing the property of those who refuse to submit to mandatory military service and who cannot afford to pay their way to exemption, the law will create another off-ramp to avoid service. However, by seizing and disposing of the assets of those wanted for service — including many who are abroad — the amendment will raise a practical barrier to return, and it will likely have a deep impact on the families in Syria of affected individuals. For Syrian refugees, the effect may be to punctuate the fact that ties with Syria itself have been irreparably severed.

5. Residential Collectives union dissolved, placed under Ministry of Housing

Damascus: On 18 December, media sources reported that the Syrian Parliament had issued a legislative decree dissolving the General Union of Residential Collectives. The Ministry of Housing and Construction will directly assume all roles and responsibilities previously carried out by the union. The union had functioned as a liaison entity, coordinating the relationship between residential collectives — which serve a role similar to homeowners’ associations — and the Ministry of Housing and Construction. The union had also facilitated the collectives’ functions, primarily the management of residential policies, the allocation of land, and the implementation of residential building projects.

Paving the way for reconstruction?

Residential collectives are quasi-governmental local entities, and are therefore bound to the policies of the Government of Syria, yet they nonetheless represent the interests of their members, often with a degree of freedom not afforded to overtly political entities. Collectives were also locally elected, and thus in some ways represented an important form of local civil society. Although this liatitude was not without limits, residential collectives have been capable of challenging Government decisions with regard to housing, or, at the very least, pushing the Government to take local interests into account. In myriad cases, collectives representing various stakeholders and sectors have succeeded in challenging state decisions, specifically those related to housing and construction (see Syria Update 18-24 September 2019 and 24 August-4 September 2019).

It is unclear to what extent the dissolution of the General Union of Residential Collectives will impinge upon individual collectives’ capacity to operate independently. The Government of Syria has justified the union’s dissolution as a move to unify and expedite requests, in the name of good governance. However, the move to bring the collectives directly under a powerful line ministry will necessarily entail a greater degree of state supervision, and it constitutes a step toward the further centralization of housing affairs within Government of Syria institutions. As such, placing the collectives directly under the Ministry of Housing and Construction may pave the way toward more seamless implementation of state-endorsed real estate and reconstructions projects. Whatever its ultimate intention, the reshuffle will have sweeping effects. The latest General Conference of the Union of Residential Collectives (2016) put the total number of residential collectives in Syria at 2,680 with 93,6710 members.

6. ‘Terrorism and money laundering’: Government closes hawala offices

Various Locations: On 18 December, local media sources reported that the Syrian Central Bank had closed the offices of money transfer and exchange agencies in various locations across Syria. On 19 December, the Syrian Central Bank clarified that the closures came in response to unlicensed transactions that, according to the statement, potentially involve terrorism funding and money laundering. On 24 December, in a post to its official Facebook page, the Syrian Central Bank stated that the vice president of the Bank had convened a meeting with the managers of local money transfer agencies, representatives of the Telecommunication and Mailing Regulatory Authority, and the Anti-Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Authority, to discuss breaches of financing laws that had resulted in the branch office closures. To date, thousands of transactions have reportedly been affected by the initiative.

In Caesar’s shadow?

Myriad factors have contributed to the Government of Syria’s closure of hawala offices, but it is impossible to ignore the potentially catastrophic impact of the U.S. Caesar sanctions that were passed into law at the end of December (see Syria Update 11-17 December 2019). The sanctions’ first order will be to determine whether the Syrian Central Bank “is a financial institution of primary money laundering concern.” Such a finding may indeed be a foregone conclusion, and a wealth of evidence gives reason to doubt whether any actions taken by the Syrian state can impact the U.S. Treasury’s determination in this respect. However, it is not impossible that the Syrian state will take action (sincerely or otherwise) to influence this determination, or to combat financial skullduggery, which is endemic inside Syria. Without doubt, the hawala system is amenable to reform. However, it is also the backbone of the crisis response; as such, the closure of money transfer offices and the implementation of restrictive exchange policies can be expected to impact programming and disrupt the basic economic functionality of economically fragile Syrian communities.

No halting the freefall

As such, it is important to frame such measures against the backdrop of Syria’s ongoing economic implosion (see Syria Update 27 November-3 December 2019). The latest initiative may further signal an attempt by the Central Bank to better control the money supply with the aim of preventing currency devaluation. Indeed, throughout Q4 2019, the Syrian street (and much of the state fiscal apparatus) was gripped by currency concerns, as they witnessed the exchange rate of the Syrian lira dip to unprecedented levels, despite facile attempts by the Government to halt the freefall (see Syria Update 13-19 November 2019). Little noticed in this respect was the Central Bank’s order to increase the so-called ‘preferential’ dollar price used for certain classes of money transfers — from 434 SYP to 700 SYP — which is likely to set a floor for the lira’s value going forward.

7. Civil and security disorder grows in Rural Damascus

Duma and Kanaker, Rural Damascus governorate: On 29 December, local media sources reported that Russian Military Police had forced the Republican Guard to leave Duma, after the latter forces conducted a raid on warehouses on the Duma-Misraba road in an attempt to establish a military outpost there. Reportedly, the Russian forces established several checkpoints in Duma and have maintained a presence in the area, along with State Security forces. Relatedly, media sources indicated that Criminal Security Forces had detained the head of Duma Local Council, Nabih Taha, on 19 December. The various justifications for Taha’s detention range from alleged corruption, to the underlying tensions that are now growing within the Duma local council itself.

Kanaker Reconciliation Committee head killed

Relatedly, on 29 December, media sources reported that an IED attack had killed the head of the Kanaker Reconciliation Committee, Bahjat Hafez. As is usual in such attacks, no actor has claimed responsibility. Notably, signs of dissent and opposition sentiments have been recurrent in Kanaker (approximately 30 km southwest of Damascus) in recent months, and demonstrations for the release of detainees have taken place (see Syria Update 4-10 December 2019).

Another Dar‘a?

The end of 2019 witnessed a marked intensification of anti–Government of Syria dissent in Rural Damascus; this has been met with a commensurate response from the Government, as it seeks to prevent latent dissatisfaction from crystallizing into outright chaos in the vicinity of the capital, as it has in southern Syria. Whereas the wholesale breakdown of security witnessed in Dar’a is unique to southern Syria, the underlying ideological, economic, and political factors that motivate it are also present in Rural Damascus — and, indeed, throughout Syria. What has permitted the breakdown of security in southern Syria is the region’s unique security fragmentation (see Security Archipelago: Security Fragmentation in Dar‘a Governorate).

To this end, it appears that the Government of Syria has prioritized the stability of Rural Damascus. In the most notable evidence of such a strategy to date, the Government has imposed severe mobility restrictions on opposition-affiliated and ‘unreconcilable’ individuals in Eastern Ghouta (see Syria Update 11-17 December 2019). For Russian forces to restore calm to these areas will require their meeting political, material, and security demands that are likely well beyond their capacity. Should this fail, further assassinations targeting Government-affiliated security actors and public employees are likely, as is a progressive breakdown of security in such communities. Should this occur, the Government will likely stamp out dissent in affected areas as it has done in much of Rural Damascus: by imposing further iron-fisted security policies.

8. Turkey deploys Syrian fighters to Libya

Tripoli, Libya: In response to a formal request for military assistance made by Libya’s Government of National Accord (GNA) on 19 December, Turkey has deployed as many as 300 Syrian opposition combatants to Libya, according to multiple Syrian and international media sources, as well as social media posts by the combatants themselves. Reportedly, the fighters are predominantly ethnic Turkmen from Jarablus and A‘zaz, in northern Syria. A large contingent of the fighters redeployed to Libya had reportedly fought under the banner of the Sultan Murad, Suleiman Shah, and Liwa Mu’tasim factions, and formerly received lethal support from the U.S. Reportedly, as many as 1,000 additional Syrian fighters have crossed into Turkey to be trained for deployment to Libya, and it is rumored that an active campaign to gain further recruits is ongoing in northern Aleppo.

Regional ramifications

For Turkey, there are multiple benefits to deploying Syrian proxies in defense of Turkish national interests abroad. Such combatants are relatively cheap (salaries reportedly exceed $2,000, but this is likely true only for technical specialists), yet these combatants are also highly effective, as many have become professional warfighters through extensive combat experience against ISIS, HTS, the Government of Syria, and various rival armed factions. Moreover, such deployment spares Turkey the potential domestic political consequences associated with putting Turkish boots on the ground to prop up Libya’s embattled GNA against its rival, the Libyan National Army (LNA), which is led by Khalifa Hifter and supported regionally by Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, and Russia, through private contractors with the Wagner Group.

The deployment of Turkey-backed Syrian fighters in Libya is likely to increase in scale and scope, in accordance with a 27 November agreement between Libya and Turkey. This bilateral agreement secured Turkey’s maritime interests and in the long term seeks to guarantee the commercial outlook of private Turkish companies in the country. In exchange, Turkey has already begun to deliver deep military support to the GNA. Within Libya, the deployment will lend credence to the LNA’s efforts to cast GNA fighters as islamists; intensify the race for external support now ongoing between the LNA and GNA; and extinguish hopes for détente between the warring factions. Regionally, further important ramifications are also clear. As Western states reassess and redirect their direct military presence in the greater Middle East, gaps are opening for other actors, namely Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Russia, to assert themselves as regional power brokers. Finally, the deployment of Syrian combatants to Libya offers a glimpse of how the protracted Syria crisis has created a fractured military proving ground, which will have spillover effects regionally.

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below.

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

What Does it Say? Control of oil fields in northeast Syria promises little financial gain for the U.S. or corporate actors.

Reading Between the Lines: While commercial exploitation of the fields is not worth the political (or geologic) risk, occupying the fields does give leverage over Damascus and Iran.

Source: Carnegie

Language: English

Date: 11 December 2019

What Does it Say? From 22-28 December, in ostensible reprisal for the killing of Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi, ISIS claimed responsibility for 106 operations, including 50 in Syria — 35 of which targeted the SDF.

Reading Between the Lines: The attacks were largely small in scale and attest to the group’s degraded capacity, but regional disturbances may open the door to greater operational space.

Source: Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi

Language: English

Date: 31 December 2019

Qardaha: ‘The Tiger’ Confronts the Assad Family’s Gangs

What Does it Say? Qardaha, ancestral stronghold of the Al-Assad family, is in the midst of a struggle as influential local gangs resist attempts by Government security forces to impose order, including by stripping the local groups of heavy weapons.

Reading Between the Lines: The foundering efforts to restore control in Qardaha speaks to a problem that will be encountered throughout Syria while demobilizing powerful local actors that have spent much of the conflict with unchecked power — and enormous extractive interests — in their communities.

Source: Al-Modon

Language: Arabic

Date: 18 December 2019

U.S. and Russian Soldiers in Syria Fist Fight

What Does it Say? A fist fight reportedly broke out between Russian and U.S. forces in Tel Tamer, after local residents accused the U.S. forces of betrayal following the partial military withdrawal in October.

Reading Between the Lines: If true, the incident suggests the implications for community acceptance of the U.S. withdrawal, but it will also be seen as evidence of Russia’s attempts to supplant the U.S. in northeast Syria, including as guarantors of the interests of the local population.

Source: Middle East Monitor

Language: English

Date: 30 December 2019

What Does it Say? In an attempt to assert greater control over the overall process, Saudi Arabia has sought to reshuffle membership of the Syrian Constitutional Committee’s opposition bloc.

Reading Between the Lines: By asserting more influence over the process, such efforts by Saudi Arabia may ultimately weaken the opposition bloc.

Source: Halab Today

Language: Arabic

Date: 29 December 2019

Soaring Fuel Prices Make Syrian Winter Even Colder

What Does it Say? As the value of the Syrian lira has collapsed, the cost of a barrel of heating fuel has jumped to $100, up from $35 last winter, pushing desperate Syrians to seek out fuel alternatives — such as wood, coal, and pistachio shells — as winter sets in.

Reading Between the Lines: Given the ongoing military offensive in northwest Syria, the overturning of the domestic fuel trade, and regional instability, this privation is likely to worsen.

Source: Al-Monitor

Language: English

Date: 1 January 2020

What Does it Say? The collapse of the Lebanese economy has prompted a search for new methods of shoring up the country, including in-kind support.

Reading Between the Lines: Whatever form it takes, support to Lebanon is likely to be contingent upon reforms the Lebanese political class is resistant to — or incapable of — making.

Source: Al-Modon

Language: Arabic

Date: 6 December 2019

Velayati Receives Arab Tribal Sheikhs in Tehran, Including Nawaf Al-Bashir

What Does it Say? Ali Akbar Velayati, advisor to the Iranian leader, met with Syrian Arab tribal leaders in Tehran

Reading Between the Lines: Tribal outreach has been a touchstone of state actors’ strategies in Syria, particularly in the northeast, where the U.S. withdrawal has opened space for actors to capitalize on their influence campaigns.

Source: Jorf News

Language: Arabic

Date: 28 December 2019

The Wartime and Post-Conflict Syria project (WPCS) is funded by the European Union and implemented through a partnership between the European University Institute (Middle East Directions Programme) and the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR). WPCS will provide operational and strategic analysis to policymakers and programmers concerning prospects, challenges, trends, and policy options with respect to a conflict and post-conflict Syria. WPCS also aims to stimulate new approaches and policy responses to the Syrian conflict through a regular dialogue between researchers, policymakers and donors, and implementers, as well as to build a new network of Syrian researchers that will contribute to research informing international policy and practice related to their country.

The content compiled and presented by COAR is by no means exhaustive and does not reflect COAR’s formal position, political or otherwise, on the aforementioned topics. The information, assessments, and analysis provided by COAR are only to inform humanitarian and development programs and policy. While this publication was produced with the financial support of the European Union, its contents are the sole responsibility of COAR Global LTD, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.