Syria Update

9 March 2020

Table Of Contents

Download PDF Version

Erdogan and Putin push pause on Idleb

In Depth Analysis

On 5 March, Russia and Turkey reached a ceasefire agreement that freezes frontlines in northwest Syria, establishes a new ‘security corridor’ along the M4 highway, and creates a framework for joint Russian-Turkish military patrols. The agreement winds down a week of intense military confrontation between Turkish and Government of Syria forces in northwest Syria — the most intense of the conflict thus far (see: Syria Update 2 March). The deal achieves the chief objectives of both Turkey and Russia. Respectively, these are halting the massive displacement crisis that Turkey views as a threat to its national security, and restoring functionality to the M4 and M5 highways, a priority for Syria’s economic vitality. However, the agreement is far from a comprehensive solution, and in large measure it merely postpones the need to address the conflict flashpoints that remain at play in northwest Syria. Cooperation mechanisms and deadlines set out for the agreement’s full implementation remain unclear. Most importantly, the agreement fails to address the fate of more than 960,000 IDPs now trapped in the embattled opposition-held enclave of northern Idleb, and it does not specify the means of addressing the presence of radical groups. As such, the agreement is an important step to de-escalate northwest Syria in the near term, but it leaves open the door to future conflict.

The Moscow Memorandum

The deal emerged from a head-to-head summit between Turkish President Recep Tayyib Erdogan and Russian President Vladimir Putin. It achieves three main actions:halting “all military

actions along the line of contact”; establishing a “security corridor” in an area that is 6 km deep to the north and 6 km deep to the south of the M4 highway; and deploying Turkish-Russian joint patrols along the M4 highway. Additionally, the memorandum reaffirmed the “determination to combat all forms of terrorism and to eliminate all terrorist groups in Syria as designated by the UNSC”. The protocol also emphasizes that “targeting civilians and civilian infrastructure cannot be justified under any pretext”, and recalls the “Memorandum on the Creation of De-Escalation Areas as of May 2017 and Memorandum on Stabilization of the Situation in the Idleb De-Escalation Areas as of September 2018 [i.e. the Sochi agreement].”

Notably, several points that will be crucial to the deal’s sustainability are not resolved. These include the future of the Turkish troops now deployed in northwest Syria, the timeframe allotted for the deal’s full implementation, and the creation of a mechanism for dealing with the massive population of displaced Syrians now effectively trapped in the zone between the newly frozen frontlines and the Turkish-Syrian border. Crucially, whether — and if so, how — these IDPs will be sheltered in place, allowed to return to Government-held communities, or be offered the option of moving onward — potentially to northeast Syria — remains unclear. Moreover, the deal fails to clarify the status of the encircled Turkish observation posts in areas south of the security corridor. Additionally, although the memorandum re-affirms the September 2018 Sochi agreement, it does not address Erdogan’s repeated demands for Government forces to withdraw to frontlines established by Sochi, thus setting up the possibility of future disputes over the two deals’ apparent contradictions.

Winners: Russia and Turkey

The Moscow deal meets the most urgent priorities of both Turkey and Russia. For Turkey, the deal succeeds by halting (or delaying) military operations in remaining populated areas in Idleb, thus preventing a new influx of IDPs toward its southern borders. For Russia, the deal secures access to Syria’s international highways (the M4 and M5), which link major cities such as Aleppo, Damascus and Latakia, a necessity for reviving internal trade.

Losers: Local Actors

Hope that the deal will prevent further violence is tempered by the reality that although the agreement guarantees Russian and Turkish priorities, it does not necessarily allow space for the ambitions of local actors (including the Government of Syria), who may seek to sabotage the ceasefire, as they have done during ceasefires in the past. Looking ahead, the opposition-held area south of the M4 highway security corridor may be a focal point of any such hostilities. The Government of Syria likely views the continued presence of armed opposition factions south of the M4 highway, including in the strategic Jabal al-Zawyeh area, as posing a continued threat to the highway. Meanwhile, armed opposition factions have repeatedly vowed their intention to restore control over territories recently captured by the Government of Syria, to include highly symbolic communities such as Ma’arrat An Nu’man and Kafr Nobol.

Radical Groups

Perhaps the greatest impediment to the Moscow deal’s future workability is the fact that it fails to create a new mechanism for dealing with extremist groups — an oversight that was fundamental to the breakdown of the Sochi agreement. As such, one potential flashpoint in the near term is the possibility of clashes between Government of Syria forces and Iran-backed militia groups on one hand, and the Syrian National Army and jihadist groups such as Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham, Hurras Al-Din, and the Turkistan Islamic Party on the other. A further concern is the continued existence of these groups, vis-à-vis Turkey, which remains tasked with resolving the fate of radical groups in northwest Syria. The foremost of these groups is Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham and its nominally independent governance arm, the Salvation Government. In addition to the potential for clashes with the Government of Syria, HTS may also come into conflict with Turkish troops or other armed opposition factions backed by Turkey. At the same time, it remains possible that separate agreements may grant scope for HTS to dissolve its formal command structures, allowing for the integration of its low-ranking fighters and civilian staff within the Syrian National Army and the Syrian Interim Government, or a new hybrid governance body. However, for extremist groups Hurras Al-Din and the Turkistan Islamic Party, such rehabilitation may not be possible. As such, on a long enough timeline, armed confrontation may be the sole path forward for Turkey.

Whole of Syria Review

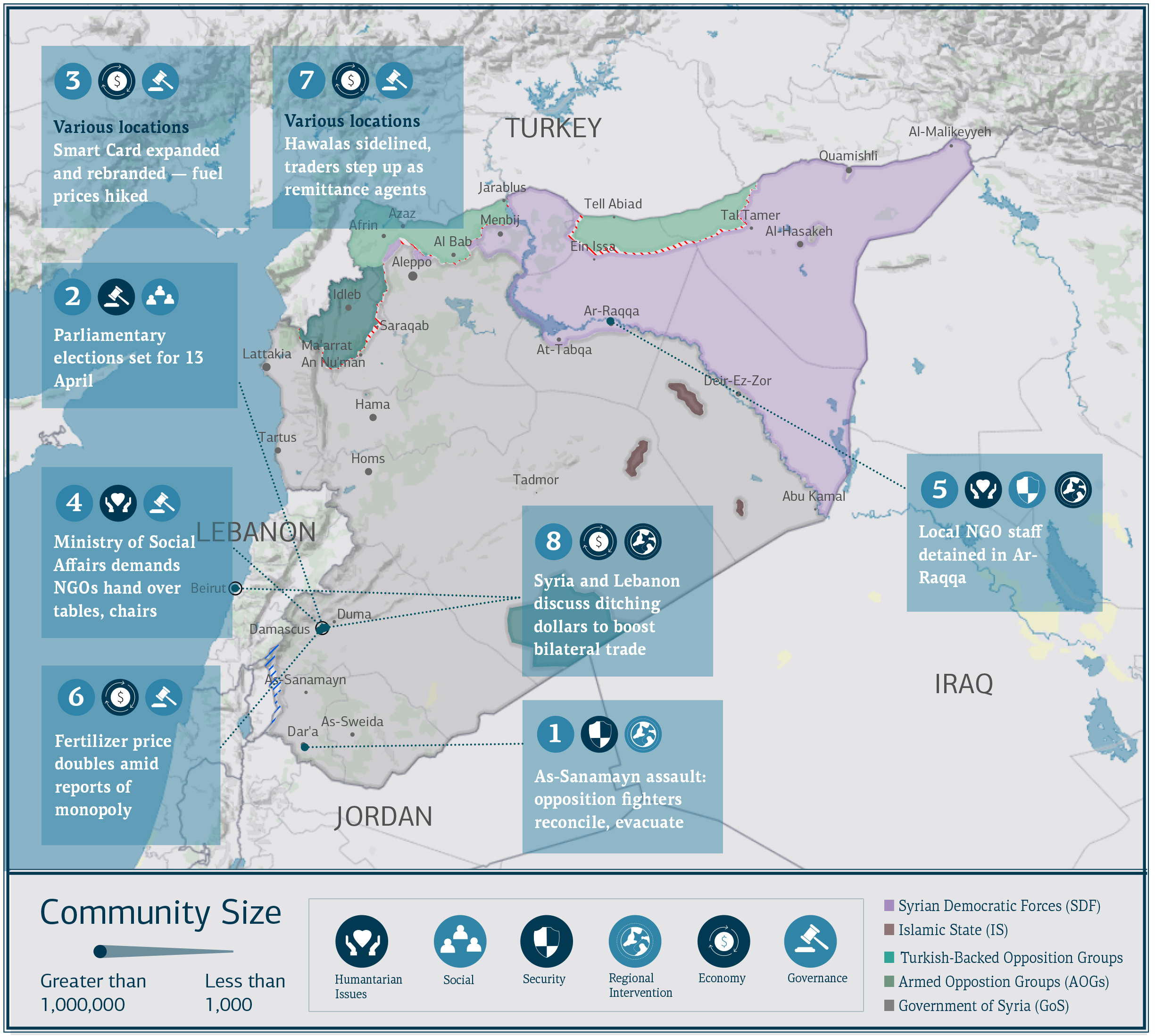

1. As-Sanamayn assault: opposition fighters reconcile, evacuate

As-Sanamayn, Dar’a governorate: On 1 March, local sources reported that the Government of Syria’s 4th and 9th Divisions, supported by Iran-affiliated militias, launched an attack on neighborhoods in northern and northwestern As-Sanamayn city. Clashes between the local As-Sanamayn Revolutionaries (Thouwar As-Sanamayn) and Government of Syria forces lasted until 2 March, amidst intense Government of Syria shelling and besiegment of the city. The clashes reportedly resulted in the death of 20 Government of Syria combatants, three opposition fighters, and four civilians, as well as an unspecified number of injuries. On 2 March, the Government of Syria established control over the embattled neighborhoods, imposed a curfew, and forced local combatants into reconciliation negotiations. Local fighters unwilling to reconcile their status and surrender their weapons to the Government of Syria are to be allowed to evacuate to Tafas and northern Syria. As of this writing, local sources indicate that no evacuees have made their way to Tafas, whereas at least 20 fighters left with their families to the Euphrates Shield area. Moreover, both sides have reportedly agreed on an extension of military service, the release of detainees through Russian mediation, and the terms of the Government’s military and security presence in the entirety of As-Sanamayn city. Notably, the assault in As-Sanamayn prompted widespread popular demonstrations in solidarity in communities throughout western rural Dar’a.

The crackdown on Dar’a is yet to come

The sudden crackdown on As-Sanamayn is, in fact, the culmination of a year of simmering tensions between the Government and the opposition combatants who have remained in power in the some quarters of the community, which avoided wholesale reconciliation during southern Syria’s reconciliation in summer 2018. The events echo a similar ‘siege’ in May 2019, in which the Government attempted to isolate the community and consolidate its control there (see: Syria Update 22 May 2019). Those efforts failed. Now, the latest developments in As-Sanamayn send a clear signal to other communities in southern Syria that Damascus remains willing to use force to impose its presence in restive areas — even if its intention to do so on a wide basis at the moment is uncertain. Finally, the use of reconciliation is particularly noteworthy. This is the first instance of community reconciliation since July 2018. The agreement is notable in that it allowed opposition fighters to evacuate to Tafas, rather than forcing them to displace to northwest Syria, as required in previous reconciliation negotiations. Any fighters who do evacuate to Tafas may find a similar pattern will play out there, as Tafas is among the communities where the Government of Syria is likely to concentrate its efforts to restore control in the future.

2. Parliamentary elections set for 13 April

Damascus: On 3 March, Syrian state media reported that President Bashar Al-Assad issued a decree setting 13 April as the date for upcoming parliamentary elections, the first to take place since 2018. The decree also stipulated that 50.8 percent of electoral slots will be allocated to farmers and workers. Notably, the announcement allows only one month for candidates to campaign before elections, and thus violates Syrian electoral law, which stipulates that elections cannot be called with less than two months’ advance notice.

No changing of the guard

The parliamentary elections are more likely to reinforce — rather than alter — Syria’s fundamental power structure, including the relationship between central authorities and local communities. The most important question to be answered by the elections concerns the way they will play out in areas that remain outside the Government’s formal control (i.e. northwest and northeast Syria). An additional concern arises in areas such as Dar’a governorate, where fluid security conditions may pose a challenge to voting. Ultimately, the last round of parliamentary elections in 2018 gave the Government of Syria a gloss of legitimacy vis-à-vis the public, and it allowed the Government to declare a step in the direction of normalcy, following its considerable territorial gains of early 2018. Although the Government of Syria has made important gains in northwest Syria in recent months, few substantive changes have registered. Looking ahead, there is little reason to expect that the new parliament will differ in any fundamental way from the one it is replacing.

3. Smart Card expanded and rebranded — fuel prices hiked

Various locations: Over the past week, new food products were added to the Smart Card subsidy system, now rebranded “electronic card” or e-card, in an effort to combat rising dissatisfaction over the system’s inefficiency. On 4 March, in an announcement by the state-owned Syrian Trade Establishment (STE), sunflower oil was added to the list of food products sold at discounted prices through the e-card system, with further intentions to add maté tea and an assortment of canned foods. Additionally, the quantities of tea and sugar allocated via the system have been bumped up, with the quota now being sold at floating market prices.

Relatedly, for the second time in less than a year, the Ministry of Domestic Trade and Consumer Protection increased petrol prices, both subsidized and unsubsidized. According to the ministry, a price rise of 25 pounds will be introduced to all petrol products, including subsidized petrol-octane 90, unsubsidized petrol-octane 90 and unsubsidized octane 95. Notably, since May 2019, vehicle owners were allocated 100 liters of petrol per month at the subsidized rates.

Smart card, dumb system?

Expanding the roster of consumer items covered by the e-card serves two essential functions for the Government of Syria: 1) as a rationing device; 2) as a tool to reduce the Government’s costs by more accurately matching distribution to household size. For consumers, however, the benefits of the e-card are disputable. Goods are frequently in short supply, and queues often stretch for hours. As a result, some Syrians have reportedly opted to purchase goods on the open market. Although market prices are higher, some Syrians are finding it most cost-effective to use the time saved for income-generating activity, rather than queuing.

Increasing fuel prices has two potential benefits to the Government of Syria, with a moderately significant impact on consumption. First, increased prices help the Government’s bottom line, which would help it cover its outlays on subsidies. Second, raising prices may be a disincentive to fuel smuggling to neighboring countries, which would take pressure off the domestic market. Notably, the impact on consumer costs will be moderate as it will not be compounded with rising transportation costs. Trucking and transportation in Syria is predominantly reliant on diesel, rather than gasoline, thus limiting the impact of the higher cost to private vehicle owners. As a result, commercial transportation costs are not expected to be passed on to consumers due to this price hike.

4. Ministry of Social Affairs demands NGOs hand over tables, chairs

Damascus: The Ministry of Social Affairs has issued an order to requisition tables and chairs from local NGOs following project closeout, according to local sources at the head of a Syrian NGO. The order applies only to NGOs that received foreign funding, including from UN agencies and INGOs.

Power of the purse

Requisitioning equipment following project closeout is a deceptively simple order that may have a wide-reaching impact. The demand may be the thin edge of the wedge, paving the way for central authorities to take possession of other equipment, office supplies, computer hardware, and physical property. From the perspective of the international Syria response, the order may thus be seen as creating a channel for indirect support to a Government of Syria line ministry.

5. Local NGO staff detained in Ar-Raqqa

Ar-Raqqa governorate: On 3 March, local sources reported that SDF security forces raided the office of a local NGO in western rural Ar-Raqqa governorate. During the raid, the SDF detained the NGO’s board chairman, as well as employees who were at its headquarters. The arrests reportedly came after the NGO signed a memorandum of understanding with the civil council in Raqqa to implement a project to rehabilitate four schools in Ar-Raqqa governorate. However, the exact cause of the detentions remains unclear. The same local sources report that the SDF has recently detained and interrogated several individuals from various local NGOs, including some receiving U.S. funding, under the pretext of occuption or ‘terrorism’ funding.

SDF fears a pro-Turkey fifth column

The Self Administration has a history of scrutinizing humanitarian organizations, yet local sources indicate that the recent detentions coincide with a trend toward heightened screening measures that begin in late 2019. These sources report that two of the detained aid workers are known for their overt opposition to the Self Administration, and were affiliated with the opposition-aligned Syrian National Coalition prior to the SDF’s bid for control in eastern Syria. To that end, local rumors circulating in Ar-Raqqa governorate suggest that the individuals are organizationally linked to armed groups backed by Turkey in Euphrates Shield areas. Such a connection faces a high burden of proof. As of yet, there are no clear signs that actors linked to Turkey have sought to re-establish ties with local NGOs in SDF-controlled areas on any systematic basis; nonetheless, the heavy scrutiny of local organizations in eastern Syria is unlikely to subside. Indeed, with the apparent pause in hostilities in northwest Syria, all eyes will turn to eastern Syria, where Turkey remains fixated on linking the Peace Spring area with Euphrates Shield areas. However, doing so would require Turkey to capture Ain Al-Arab (Kobani), a community with deep symbolic significance to Syrian Kurds.

6. Fertilizer price doubles amid reports of monopoly

Damascus: On 3 March, media sources reported that the Government of Syria has doubled fertilizer prices, which will reportedly take effect starting in April. Notably, local sources indicated that the increase coincides with a chain of events in which a prominent businessman has purchased the entirety of the Government’s supply of fertilizers. Meanwhile, the Syrian Agricultural Bank has reportedly initiated loan offers for farmers to purchase fertilizers at the new prices.

The last straw?

Holistically, Syrian agriculture is at a crisis point under the accumulated weight of pre-conflict liberalization, wartime deprivation, destruction of vital infrastructure, and pricing models set by state authorities who are increasingly being driven to tolerate the capture of entire industries. (A useful primer covering these dynamics is Cultivating a Crisis: the political decline of agriculture in Syria, a study published by European University Institute for Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) program, a collaboration between EUI and COAR.) At present, it remains unclear whether the latest increase in fertilizer prices is the result of the monopoly by key suppliers, or a more benign — and coincidental — outcome of market fluctuation. Either way, the costs borne by farmers are expected to continue to rise, as agricultural subsidies drop (see: Syria Update 10 February), the Syrian pound depreciates, and fuel prices spike. Most notably, this threatens both the productivity of Syria’s beleaguered agricultural sector, as well as the nation’s food security.

7. Hawalas sidelined, traders step up as remittance agents

Various locations: On 3 March, media sources reported that Syrians have increasingly resorted to alternate channels for receiving remittances from abroad, in response to the progressive closure of traditional avenues for money transfers, including the mounting pressures facing hawala agents. According to local sources, Syrians seeking cash from abroad are now increasingly reliant upon an informal system — not new, but of growing prominence — that relies upon cross-border connections among commercial traders. In effect, traders inside Syria disburse cash to borrowers. Those borrowers rely on guarantors outside Syria, who advance funds to commercial suppliers based outside the country. In practice, the loop is closed when the local traders inside Syria conduct commercial transactions with their suppliers. Traders reportedly charge a commission of around 2 percent to 5 percent.

Backchannels to the fore

Remittances have long played a central role in Syrians’ livelihoods strategies. However, with traditional hawala networks sidelined, few formal alternatives have appeared. As a result, Syrians remain motivated to use informal channels by a desire to evade state surveillance, the unavailability of foreign currencies, and the poor conversions offered by formal channels. In parallel, the Government of Syria’s push to stabilize the pound and draw remittances into the formal market has, to this point, failed. A crackdown on transfer agents that began in late 2019 has intensified with a concerted campaign to shutter exchange offices this year. In order to keep money flowing into the country, in February the Central Bank issued a new policy allowing Western Union transfers to enter Syria at 700 SYP/USD. The new conversion was an improvement over the official rate of 435 SYP/USD, but it fell far short of closing the wide gap with the market rate, approximately 1,065 SYP/USD. The timing could not be worse. Syria’s economic implosion has been exacerbated by the shrinking inflow of remittances from Lebanon — a nation that is also in economic freefall, and which has been by some estimates the second-largest source of total remittances to Syria. These adverse conditions are likely to persist, and so will Syrians’ reliance on alternate means of moving money.

8. Syria and Lebanon discuss ditching dollars to boost bilateral trade

Beirut and Damascus: On 27 February, media sources reported that Lebanese Minister of Industry Imad Hob Allah and Secretary General of the Syrian-Lebanese Supreme Council Nasri Khoury convened a meeting to discuss bilateral trade between Lebanon and Syria. Reportedly, the meeting revolved around two points: encouraging formal trade, and stemming the rise of smuggling between Lebanon and Syria. Notably, the discussions also touched on the possibility of using local currencies to trade in basic materials, and reducing Syrian transit fees, which increased from 2 percent to 10 percent in October 2018, before the reopening of the Nassib-Jaber border crossing between Syria and Jordan.

Try, try again

Both Lebanon and Syria have ample incentive to jumpstart bilateral trade and reduce their reliance on dollars. What is now unclear, however, is what mechanism can be introduced to serve this need. Interrupting incipient smuggling networks will no doubt be an important part of supporting both states’ budgets. However, all previous efforts by Lebanon and Syria to strike while the iron is hot and improve economic cooperation have seemingly brought little benefit. The measure faces long odds, yet success is by no means out of reach, and the need to find success in this arena has never been greater.

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below.

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

Government fails again to award wheat import contract

What Does it Say? The Government of Syria has once again announced plans to import wheat, yet the failure to finance past bids makes it clear that Syria’s financial troubles remain deep.

Reading Between the Lines: At best, Syria’s financing woes are a serious fiscal concern; at worst, they raise the prospect of looming food security crisis.

Source: Syria Report (paywall)

Language: English

Date: 4 March 2020

Erdogan and Putin: The end of the affair

What Does it Say? The conflict in Syria has pitted Russia and Turkey against one another as they support opposing sides, leading to a rift between Erdogan and Putin.

Reading Between the Lines: While it is true that the relationship between Russia and Turkey has been strained, the rupture between Erdogan and Putin has been overstated, in large part by analysts who hope — unrealistically — to see the relationship disintegrate.

Source: Middle East Eye

Language: English

Date: 3 March 2020

What Does it Say? The escalation in Idleb can be read not as a prelude to heightened conflict between Turkey and Russia, but as a negotiation tactic to usher in new Russian-Turkish understanding in Syria.

Reading Between the Lines: The article rightly emphasizes that neither Turkey nor Russia wishes for all-out warfare in Idleb. As we have written at length, the Russia-Turkish relationship is a global one, and Idleb — though important — is merely one dimension.

Source: Carnegie

Language: English

Date: 29 February 2020

The reordering of the Syrian political economy

What Does it Say? The article argues that in the absence of a sustainable conclusion to the Syria conflict, an ‘authoritarian peace’ will emerge, in which violence and discontent will continue.

Reading Between the Lines: Ultimately, such an outcome will sow the seeds of further revolt.

Source: Salon Syria

Language: English

Date: 1 March 2020

What Does it Say? The interview sheds light on the living conditions of the Syrian-Sudanese community in Damascus, including the challenges of poverty, marginalization, and racism.

Reading Between the Lines: Syrians of Sudanese origins contribute to Syria’s ethnic patchwork, and are a particularly marginalized group, facing discrimination from other Syrians, as well as the Government, itself, which has denied many citizenship, notwithstanding that some have lived in Syria their entire lives and fought in the Syrian army.

Source: Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi

Language: English

Date: 04 March 2020

Russian delegation meets the dignitaries of the As-Sweida, what was the response to their demands?

What Does it Say? A Russian delegation met with local leaders in As-Sweida; Russia emphasized the voluntary return of Christians, while the As-Suwayda locals highlighted the challenges of kidnappings and missing persons.

Reading Between the Lines: For a number of reasons, Russia has prioritized nominal support of Christians in Syria, yet the foremost challenges in As-Sweida relate to the area’s prominence as the seat of Syria’s Druze community. Squaring these concerns to ease local tensions and repair the area’s relationship with Damascus will, therefore, require grappling with the Druze community’s interests with greater sensitivity.

Source: Suwayda24

Language: Arabic

Date: 4 March 2020

Syrians in Tripoli: Anxiety and aspirations

What Does it Say? The economic crisis in Lebanon is having dire effects on Syrian refugees in the country, who were already vulnerable.

Reading Between the Lines: As Lebanon’s economic crisis deepens, Syrian refugees are at a particular risk of being made scapegoats.

Source: Al Jumhuriya

Language: English

Date: 27 February 2020

‘SANA’: For the fifth time in 2020, Israeli bombing of targets in Syria

What Does it Say? On 5 March, Israel reportedly bombed targets in Syria, marking its fifth series of airstrikes in Syria since the beginning of 2020.

Reading Between the Lines: Israeli airstrikes in Syria are becoming a more regular occurrence. This growing frequency is aided by the fact that Syria has no clear means of preventing such attacks, and it cannot retaliate without risk of serious escalation.

Source: Enab Baladi

Language: Arabic

Date: 5 March 2020

What Does it Say? The Libyan Al-Wefaq government condemned the Government of Syria’s reopening of the Libyan embassy in Damascus, stating that it was a breach of international law to deal with parallel governing bodies.

Reading Between the Lines: As with any embassy opening, the move heralds the further normalization of the Government of Syria — if not on the wider international stage — then within its broader regional context.

Source: Sputnik

Language: Arabic

Date: 4 March 2020

The Wartime and Post-Conflict Syria project (WPCS) is funded by the European Union and implemented through a partnership between the European University Institute (Middle East Directions Programme) and the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR). WPCS will provide operational and strategic analysis to policymakers and programmers concerning prospects, challenges, trends, and policy options with respect to a conflict and post-conflict Syria. WPCS also aims to stimulate new approaches and policy responses to the Syrian conflict through a regular dialogue between researchers, policymakers and donors, and implementers, as well as to build a new network of Syrian researchers that will contribute to research informing international policy and practice related to their country.