Syria Update

22 June 2020

Table Of Contents

Download PDF Version

Syria is already a failed state. Will the Caesar sanctions make it more ‘fierce’?

In Depth Analysis

On 17 June, the U.S. Department of the Treasury officially enacted the sanctions contained in the Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act, thus beginning an inauspicious new phase of the long Syria conflict. The sanctions targeted 39 Syrian individuals, including President Bashar Al-Assad and his wife, Asma, in addition to members of the extended Al-Assad family, senior military leaders, and business executives. Many of the sanctioned individuals were already designated under existing U.S. sanctions. However, the opening broadside can be read as a signal that the U.S. administration will employ the sanctions with maximum force. This is likely to have a significant chilling effect on foreign individuals, governments, or corporations by deterring engagement in a broad range of sectoral activities that are now sanctionable under the U.S. law (see: Syria Update 11-17 December 2019).

The sanctions have been the focus of a wide array of analytic reports, newspaper columns, panel discussions, and advocacy briefs in recent weeks. Many have assessed the sanctions primarily as a policy instrument. Certainly, pertinent policy questions are raised by the sanctions. For instance: how can the international community preserve bedrock norms as the Government of Syria consolidates its authority? Are the sanctions calibrated to achieve intermediate-stage goals, or do they effectively require Syria’s ruling regime to voluntarily step down? What mechanisms exist for international coordination to ensure harmony among U.S. sanctions and EU restrictive measures? Such questions are critically important, yet they overlook fundamental realities about the nature of the Syrian state. Arguably, to understand the impact of the sanctions, it is necessary to first appreciate the nature of the Syrian state itself. Several critical mischaracterizations of Syria are currently widespread.

Syria is merely a failed state. Syria certainly is a failed state, yet the fragility-based metrics that underpin development and post-conflict reconstruction orthodoxy do not necessarily apply in this context. Syria is best characterized as a “fierce state” in which the ruling elite has fortified its rule by undercutting virtually every institutional pillar of traditional state ”antifragility.” In functional terms, this means that initiatives — including sanctions — that are designed to weaken or isolate state institutions will not necessarily create leverage over the Syrian regime itself. The regime and the state are not synonymous (see: Syria Update 15 June).

The Syrian regime seeks to avoid state collapse. The war itself has shown the regime’s willingness to sacrifice the state itself in the pursuit of its own institutional self-preservation.

If existing regime stakeholders do not make concessions, a rearguard within the regime will. This premise rests on the notional likelihood of challenges to the current Syrian regime. This possibility cannot be ruled out. However, the long arc of the Syria conflict has been immensely humbling for the international community. Conventional wisdom has often crumpled on contact with hard realities in Syria. Decision-makers must beware of the law of unintended consequences when seeking to bring about change.

Syrians themselves view the downfall of the regime as necessary. Many Syrians do reject the Al-Assad regime at all costs, and therefore support the sanctions. However, throughout the conflict, opposition control also brought with it checkpoint economies, service shortfalls, extortion, graft, and inept governance. After nearly a decade of internecine conflict, many Syrians are simply exhausted. Opposition sentiment remains alive in many areas, and the successes of opposition-led governance are remembered. However, it is not guaranteed that these memories will manifest as overt resistance to Al-Assad. Critically, there is no clear mechanism in place to convert such resistance to meaningful political action.

Crossing the Rubicon

Ultimately, there is little value in now re-litigating the logic of the sanctions themselves. The die is cast. The Caesar sanctions are now in effect, and the international Syria response is likely to confront several critical realities going forward.

Donor and bank requirements will become more rigid. In comparable contexts, aid actors almost universally identified heightened due diligence requirements as an impediment to programmatic activities. In addition, bank de-risking will cause financial institutions to avoid carrying out transactions to avoid committing inadvertent violations. Together, these conditions will produce a chilling effect that will hinder humanitarian action.

Humanitarian exemptions are piecemeal, weak, and ineffective. Humanitarian exemptions are built into the Caesar sanctions, but challenges remain. First, applying for exemptions increases operational costs, and will consume more time and resources to satisfy funding agency requirements. Second, seeking such exemptions from political bodies may affect the perceived independence of humanitarian actors and make the processing of some funding streams easier than others. Third, although some goods are allowed through the wall raised by sanctions, narrow humanitarian exemptions allow only targeted relief that have limited impact in the face of Syria’s wholesale economic destruction.

Providing timely and relevant programming will become more difficult. Onerous compliance requirements will delay response times and reduce aid actors’ agility and speed. As a result, unexpected events, the rapid onset of harsh winter conditions, or military offensives may produce unforeseen needs that will be difficult to address. Few local NGOs stockpile key items necessary to respond to unanticipated emergency needs, and few, including the largest organizations, are supported by the unrestricted funding needed to plug such gaps. Even routine programming like winterization or agricultural support could be impacted.

The localization agenda will be undermined. The Caesar sanctions will complicate humanitarian action in Syria holistically, but they will have a disproportionate impact on local partners and smaller NGOs. More stringent due diligence procedures for local and implementing partners is likely to hinder programming. The international community’s commitment to localization is already flagging. These conditions will strain it further.

Revolution redux: Al-Assad must go, or we burn the country

Certainly, the conditions facing the international response are daunting, yet the Syria context itself is also likely to change. The sanctions contain a five-year sunset provision. However, in a political sense, far more pathways exist to renew and expand the sanctions than to remove them. Statements from U.S. officials suggest that the sanctions are unlikely to be lifted, even if U.S. President Donald Trump does not win a second term. As a result, the sanctions probably will remain in place irrespective of changing political winds. Donors and aid actors on all levels must, therefore, consider the implications for the Syrian context itself.

The conflict has reduced Syria to a nearly pre-industrial state. The sanctions are designed to lock in that status and leverage future economic and infrastructural rehabilitation for political change. The conditions that are likely to result will degrade Syria’s already meager economic capacity over time, thus increasing needs.

The poor will continue to lose. Women and children will suffer the most. Sanctions have a greater negative medical and social impact on women, as they bear the brunt of social and economic displacement and upheaval.

The rich will continue to profit. Comprehensive economic sanctions on an authoritarian regime will likely increase the power and profit of war economy actors who control black market activity and smuggling.

Vital sectors will remain non-functional. Health, WASH, and agricultural sectors are likely candidates for humanitarian exemptions to the sanctions. However, targeted interventions in these sectors are ineffective without the necessary infrastructure provided by health facilities, pharmaceutical manufacturing, refrigeration or cold-storage chains, electricity grids, generators, road networks, value chains, or a functional market economy in which to sell produce. Already, such infrastructure is inadequate or non-existent. The sanctions will erode this further, thus fueling a vicious cycle of growing needs and increasingly inefficacious response activities as Syrians become more aid dependent.

The Syrian state will continue to fail. A lack of vital infrastructure and public revenues will further weaken the remaining institutions of the Syrian state. Support from regional allies will provide some relief, but service provision is expected to worsen, and state functionality will degrade over time. Such conditions will produce worsening outcomes in education and health. In turn, a lack of opportunities is likely to prompt flight by the skilled technicians and trained staff whose ingenuity will be more needed as resources dwindle. This will accelerate the state’s decline and make the task of stabilizing Syria more difficult in the future.

The root causes of the conflict will be exacerbated. Among the most important drivers of the conflict were elite capture, economic inequality, a lack of social mobility, totalitarian rule, and widespread popular misery. The sanctions will aggravate these conditions. From a programming perspective, these root causes of the conflict cannot be resolved by humanitarian activities alone. Until development actors can catalyze systemic change, prevailing conditions will intensify the drivers of instability.

The regime itself may be strengthened. The sanctions may have the perverse unintended consequence of forcing the Syrian regime to circle the wagons and purge its ranks of potential challengers. Measures designed to isolate the regime may increase paranoia and heighten the self-protective instincts that have safeguarded the regime throughout nearly a decade of conflict.

Much will change in the next five years in Syria. It is incumbent upon response actors to anticipate such changes and conform their activities to evolving realities. As we have written, fully isolating Syria is unlikely to succeed strategically. While normalizing relations with Al-Assad is also counterproductive and politically undesirable, some conditional engagement in Government of Syria-held areas is possible, including through civil society actors (see: Syria Update 14-20 March 2019). Only five years ago, in September 2015, U.S. President Barack Obama stated at the UN General Assembly that Al-Assad “must go.” Within the Western policy establishment, the view that Al-Assad must go — at all costs — has remained a bedrock principle, yet the Syria conflict has changed dramatically since then. Historical precedent is not encouraging. The UN sanctions on Iraq in the 1990s are generally understood as one of the most consequential humanitarian failures in the name of global policy in living memory. Despite the reassurances of officials, it is not clear that the current approach in Syria has internalized that regret or that it has been calibrated to avoid repeating such mistakes. These days, there is little good news in Syria. If hope is to be found, it lies in the fact that there is still time to retool response approaches as the Syria crisis enters this new phase.

Whole of Syria Review

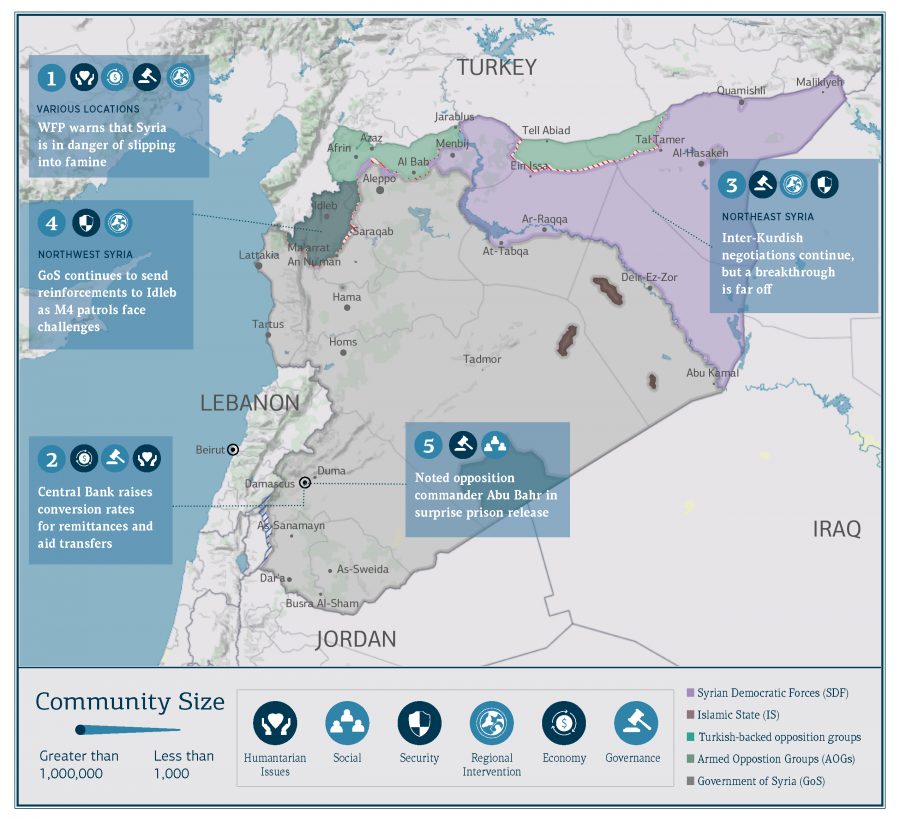

1. WFP warns that Syria is in danger of slipping into famine

Various Locations: On 12 June, media sources reported that World Food Program Executive Director David Beasley warned that “a famine could well be knocking on [the] door” if Syria’s economy continues its downward spiral. In recent weeks, there has been a steep rise in prices and a severe shortage of basic commodities as the Syrian pound depreciated to record lows. At present, WFP estimates around 9.3 million people in Syria are food insecure, with more than two million more at risk – a rise of approximately 42 percent during the past year.

A clarion call: Syria is at a tipping point

As economic and food security conditions worsen, the need to ensure sufficient supplies of wheat to the Syrian population is becoming increasingly urgent. While this year’s national wheat harvest is considered relatively successful, a three-way competition for strategic wheat crops has underscored the uncertainty inherent to food access in Government-held areas in particular, due to the barriers preventing the Government of Syria from procuring domestic wheat harvests or securing imports (see: Syria Update 8 June). With the enactment of the Caesar sanctions, the economic circumstances experienced by Syria’s middle and lower classes will deteriorate further, and the capacity of the already dysfunctional health and agricultural sectors will be put to the test. Development-sector research indicates that the economic impact of sanctions manifest sharply within the first two years of enactment — with women and children suffering the most. Most worrying is the fact that in Syria, food security will be especially difficult to ameliorate due to the economic and political isolation that will make it all but impossible to address the system-wide, multi-layered challenges that undercut the functionality of the health and agricultural sectors. Syria is at a tipping point, and there may be no easy means of rebalancing.

2. Central Bank raises conversion rates for remittances and aid transfers

Damascus: On 17 June, the Central Bank of Syria increased the conversion rate for inbound foreign wire transfers from 700 SYP/USD to 1,256 SYP/USD, in parallel with a rise in the “preferential rate” for transfers made by humanitarian and diplomatic actors, to 1,250 SYP/USD. Reportedly, the current parallel market rate sits at 2,700 SYP/USD. Amid the deterioration of conditions to crisis levels, Iran has reportedly declared its continuing intention to provide economic support to Syria through a credit line that is believed to cover basic necessities such as fuel, medicine, flour, and yeast, although specifics are notoriously difficult to pin down. Of note, economic volatility has continued to have a pronounced impact in northwest Syria. Local media sources reported that the Salvation Government will begin to pay administrative salaries in Turkish lira, following the introduction of the currency in small denominations in northwest Syria.

Currency chaos

The Syrian pound has registered modest gains against the dollar in the past two weeks, yet this is likely to be a brief interlude for the currency, not a long-term stabilization. Despite the marginal improvement, the new conversion rate for inbound transfers is already out of date, and it values the Syrian pound at more than double its actual market rate, while further decline is viewed as inevitable. In terms of practical effect, the change to the preferential rate will boost humanitarian actors’ purchasing power, but the realignment is modest, and budgets will shrink as parallel values diverge from fixed rates. As far as Syrians living abroad are concerned, the increased rate provides only modest incentive for additional wire transfers, but in many cases, incentives are moot. Remittances are an important pillar of support to Syrian communities, and Syrian workers in Lebanon reportedly transfer some 60 percent of their earnings back to Syria, with few alternatives available. For such individuals, a boost to the rate will be welcome, but individuals will likely continue to seek out alternatives wherever possible. Moreover, the Caesar sanctions will bring greater scrutiny to transfer agencies, which may err on the side of over-compliance as a result. This too will impact Syrians abroad, particularly in Lebanon.

The gap between official and parallel rates has also had a far-reaching impact on the conflict itself. Most notably, it has driven territorial actors to dump Syrian pounds in favor of more stable alternate currencies. As such, the Salvation Government’s announcement that it will ditch the Syrian pound and begin paying salaries in Turkish lira is a pragmatic — and expected — maneuver to stabilize administrative costs, and it follows the lead set by Syrian Interim Government-linked entities. In that respect, Iran’s renewal of its commitment to a Syrian credit line is both strategically expected and of little risk, given Iran’s own broad exposure to U.S. sanctions for a laundry list of issues.

3. Inter-Kurdish negotiations continue, but a breakthrough is far off

Northeast Syria: On 17 June, media sources circulated an agreement reached by various Syrian Kurdish parties which signaled their intent to engage in continuing joint negotiations over military, administrative, and political rapprochement. The agreement set the stage for a new round of talks sponsored by the U.S., and it is a preliminary step that adopts the 2014 Duhok agreement as a frame of reference for the control of the Self Administration in northeastern Syria. Of note, the Duhok agreement stipulated the creation of a joint Kurdish council to rule Self Administration-controlled areas. Not for the first time, internal factional disagreements are an impediment to detente. Media sources reported that the Kurdish National Council (KNC) has objected to the participation of the National Union Coalition, which includes 25 Kurdish parties that are under the Self Administration umbrella, as a standalone entity in the negotiations. Members of the KNC have reportedly claimed that the National Union Coalition’s independent representation is merely intended to mask the dominance of the Democratic Union Party (PYD) within the Self Administration, beneath a facade of a multi-party rule, and therefore risks derailing the negotiations.

The enemy of my enemy

Despite numerous initiatives to bring the parties together, previous negotiations between the KNC and the PYD have borne little fruit. Tangible outcomes to date include the easing of restrictions of KNC member parties’ political activities in the Self Administration-controlled areas and the release of political prisoners (see: Syria Update 11 May). However, negotiations have thus far failed to produce meaningful cooperation between KNC and PYD within the Self Administration. The most pertinent of the deep cleavages that continue to split Syria’s Kurdish parties are ideological and relational. The PYD’s ideological linkage with the PKK brings it into inherent conflict with the KNC, which has been closer to the Government of Turkey and the formal Syrian opposition. Both parties have proven resistant to making the concessions that will be needed to form a unified Kurdish front in northeast Syria, despite the power such a bloc would yield. Naturally, regional political considerations are a factor. The U.S.’s uncertain role in northeast Syria is one such condition, but the KNC’s linkages with Turkey and Iraqi Kurdish factions restrict the real political mobility of the KNC. Changing economic circumstances, humanitarian access conditions, and geopolitical pressures may prompt unexpected or rapid shifts in relations in northeast Syria, but the hurdle to pan-Kurdish detente is high.

4. GoS continues to send reinforcements to Idleb as M4 patrols face challenges

Northwest Syria: On 15 June, local media sources reported that the Government of Syria has continued to strengthen its military presence along the frontlines in Idleb by deploying additional reinforcements to the area. The reported trigger for the deployments is the failure of Turkish forces to clear a path for unmolested joint Turkish-Russian military patrols on the M4 by the 14 June deadline. Nonetheless, local sources indicated joint patrols are ongoing, but they continue to meet local resistance, including by civilian protesters and Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS). Of note, one such patrol was targeted with a landmine near Al-Qiyasat in the southern Idleb countryside, damaging a Russian military vehicle. In parallel, continuous violations of the ceasefire agreement have been recorded, with limited instances of Russian and Government of Syria airstrikes and shelling taking place.

New operations room, new reinforcements

Despite the widespread rumors that a new military offensive is just around the corner in northwest Syria, concrete indicators are not yet apparent. That said, activities on both sides of the frontline suggest that renewed fighting may not be far off. In addition to the mounting Government of Syria military presence, Turkey has also maintained a military presence in northwest Syria. Closer to ground level, continuing challenges to the M4 patrols are now an axiomatic display of resistance by local communities and HTS to further Government of Syria or Russian pushes northward. Other groups are also gearing up for a fight. Local sources reported that various Islamist factions created a new joint military operations rooms, “Fa Athbutou” (lit. “be firm!”). Reportedly, the initiative was already targeted by a U.S.-led coalition drone strike that killed two of its leaders. While there is no hard indicator that a resumption of large-scale hostilities is imminent, nearly all the actors present in northwest Syria continue to put chess pieces on the board.

5. Noted opposition commander Abu Bahr in surprise prison release

Damascus: On 18 June, local media sources reported that the Government of Syria released from prison the prominent reconciled opposition commander Muawia “Abu Bahr” Boqai. There is little clarity surrounding the circumstances of Abu Bahr’s release, or the conditions of his imprisonment on 10 October 2018 (see: Syria Update 24 October 2018). Of note, Abu Bahr was a prominent commander in Liwa Al-Awal, which was dominant in Barzeh and Qaboun until Eastern Ghouta’s phased reconciliation and capitulation under Government of Syria siege in early 2018. Abu Bahr played a pivotal role in steering the reconciliation negotiations and later remobilized with a pro-Government of Syria militia.

Gaps in reconciliation

Abu Bahr’s release was thought to be highly improbable, not least because it has apparently followed a prison term involving stints in two of Syria’s most infamous prisons: Sednaya and Adra. As such, Abu Bahr’s sudden reappearance raises more questions than it answers. However, the episode does point to three important realities that remain important in reconciled communities and more broadly throughout Syria. The first concerns the limitations to reconciliation as a framework for amnesty. Local sources report that Abu Bahr was arrested after multiple legal cases were filed by community members over his activities during the opposition period. This occurrence highlights an implicit gap in reconciliation: although the process does square an individual’s status with central authorities, it does not eliminate civil liability with the community. Second, Abu Bahr’s economic interest in a rubble clearance business is notable. Reportedly, economic competition brought Abu Bahr into direct conflict with prominent Government-linked enterprises, which highlights the continuing contest over resource capture in post-conflict communities as Syria’s overall war economy contracts. Finally, the release calls attention to the lasting political salience of the detainee file. Detentions remain a key driver of social friction throughout Syria. To date, numerous amnesties and the concerns generated by COVID-19 spreading in carceral facilities have raised hopes of a large-scale release, but these hopes have proven false.

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below.

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

‘$42b annual non-oil export target achievable’

What Does It Say? The Iranian Head of the Export Confederation Mohammad Lahouti stated that the goal of increasing non-oil exports to 42 billion is achievable by March 2021, despite the impacts of COVID-19.

Reading Between the Lines: Considering Iran’s strong economic ties with Syria, the degree to which it continues to bank on its bilateral trade relations with Syria as an economic pillar is notable, particularly as the impacts of the Caesar sanctions will lock in Syria’s status as a poor, isolated pariah state with little foreign purchasing power. For the foreseeable future, maintaining relations with Syria will likely prove expensive.

Source: Tehran Times

Language: English

Date: 15 June 2020

Syrian company wins tender of al-Hejaz Railway Station investment project in Damascus

What Does It Say? A private Syrian company has won the bid for a large investment project, which will be constructed next to the historical Al-Hejaz Railway Station.

Reading Between the Lines: The new construction plans have been met with great criticisms amongst locals who fear that the new complex will overshadow the historic architecture, and it is a signal that — as in Lebanon — post-conflict reconstruction in Syria risks marginalization cultural heritage in the interest of profit-seeking re-development.

Source: Enab Baladi

Language: English

Date: 16 June 2020

ISIS on the Iraqi-Syrian Border: Thriving Smuggling Networks

What Does It Say? In a paper series on the state of ISIS, the author discusses the means of undermining ISIS’s support base throughout the Syria-Iraq frontier, which offers it the governmental and security vacuum it needs to survive.

Reading Between the Lines: While ISIS no longer has an undisputed territorial stronghold in Syria, its guerrilla tactics and sleeper cells have made for effective methods of continuing ad-hoc attacks in the rural hinterlands that stretch from central Syria to southern Iraq.

Source: Center for Global Policy

Language: English

Date: 16 June 2020

Starving or saving the Syrians

What Does It Say? Supporters of the Caesar sanctions argue that they will eventually translate into meaningful political concessions from Damascus.

Reading Between the Lines: In an authoritarian system, however, it is extremely rare that a regime gives in to such pressure. Instead, the sanctions will take root at the expense of the Syrian people, who will suffer from the sanctions adverse consequences as they fall further into poverty and food insecurity.

Source: Al Jumhuriya

Language: Arabic

Date: 16 June 2020

How northwest Syria is preventing the spread of coronavirus against the odds

What Does It Say? Local organizations in northwest Syria are working to implement virus warning and surveillance systems and communicate important health information with IDPs through Whatsapp and other social media platforms.

Reading Between the Lines: While community engagement and local resources have been mobilized and scaled up through the ‘Volunteers Against Corona’ campaign, such efforts will fall short of aiding vulnerable communities of northwest Syria in their fight against COVID-19 without the support of the international community.

Source: King’s College London

Language: English

Date: 15 June 2020

The Role of Philanthropy in the Syrian War: Regime-Sponsored NGOs and Armed Group Charities

What Does It Say? The Syria conflict coincided with the Government of Syria’s liberalization and consequent withdrawal from service and aid sectors. As a result, in Government-controlled areas, Government-organized NGOs (GONGOs) and loyalist charities were instrumental in filling gaps, often in loyalist communities.

Reading Between the Lines: The instrumentalization of aid is by no means novel to the Syria context. However, it does call special attention to the degree to which local analysis, conditionality, and the willingness to abandon projects due to interference or aid partiality are important dimensions of a response in the Syrian context.

Source: European University Institute

Language: English

Date: 11 June 2020

What Does It Say? The article notes that deteriorating economic conditions in Syria challenge Assad’s grip on power, which the Caesar sanctions are likely to upset further.

Reading Between the Lines: Seldom have economic sanctions succeeded in regime change. Rather, the historical record shows that in totalitarian states, such sanctions frequently succeed only in tightening the ruling regime’s grip on power.

Source: Foreign Policy

Language: English

Date: 12 June 2020

What Does It Say? Syria is currently experiencing the effects of full-on economic collapse, which will only continue as the Caesar sanctions set it.

Reading Between the Lines: The sanctions are likely to exacerbate the deteriorating living conditions, and there is the implicit risk that the Government of Syria will succeed in converting the misery of Syria’s lower and middle class into anger at the West.

Source: Center for Global Policy

Language: English

Date: 15 June 2020

The Wartime and Post-Conflict Syria project (WPCS) is funded by the European Union and implemented through a partnership between the European University Institute (Middle East Directions Programme) and the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR). WPCS will provide operational and strategic analysis to policymakers and programmers concerning prospects, challenges, trends, and policy options with respect to a conflict and post-conflict Syria. WPCS also aims to stimulate new approaches and policy responses to the Syrian conflict through a regular dialogue between researchers, policymakers and donors, and implementers, as well as to build a new network of Syrian researchers that will contribute to research informing international policy and practice related to their country.