Syria Update

13 July 2020

Table Of Contents

Download PDF Version

A pyrrhic victory for aid actors: cross-border resolution extended, but weakened

In Depth Analysis

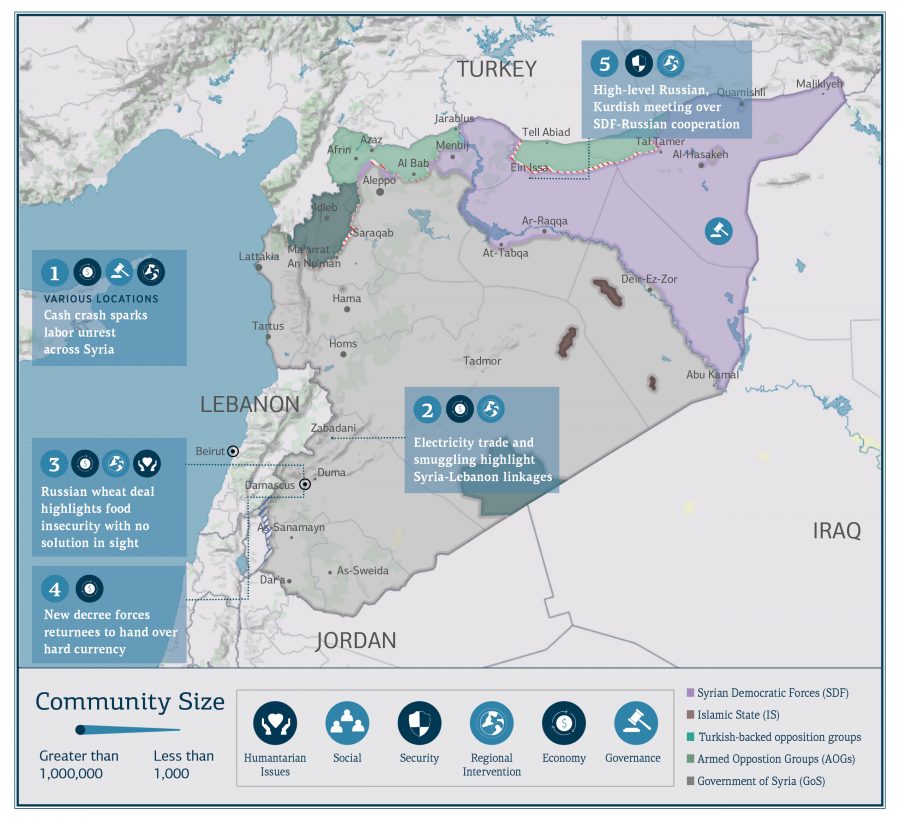

Following days of uncertainty over competing draft resolutions and dueling vetoes in New York, the UN Security Council has re-authorized cross-border humanitarian aid to Syria under the UN umbrella, albeit at diminished capacity and under the storm cloud of dubious prospects for renewal in a year’s time. On 11 July, the UN Security Council voted[footnote]The resolution passed with yes votes by Belgium, Estonia, France, Germany, Indonesia, Niger, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, South Africa, Tunisia, United Kingdom, United States, and Vietnam. Abstaining from voting were China, Dominican Republic, and Russia.[/footnote] in favor of Resolution 2533 to extend a pared-back version of the cross-border authorization, UN Security Council Resolution 2165 (2014). The new authorization permits UN convoy access exclusively through northwest Syria’s Bab Al-Hawa. All other crossings authorized by the landmark 2014 resolution — Al Yarubiyah in the northeast, Al-Ramtha in the south, and Bab al-Salamah in the northwest — have been rendered redundant or decommissioned through the progressive military and diplomatic initiatives spearheaded predominantly by Russia (see: Syria Update 13 January).

The vote is a partial victory for aid actors seeking to respond to rising humanitarian needs in Syria, but this victory is likely to be pyrrhic — and temporary. That the measure will last for 12 months, rather than six, is a mercy to long-term response planning. However, by constraining access to a single crossing point, the resolution narrows the scope of UN cross-border aid to Syria, and its passage stoked intense diplomatic confrontation that is likely to flare-up once more when the resolution nears its expiry on 10 July 2021.

In the aggregate, Resolution 2533 advances Russia’s long-term project to roll back international access to Syria, in the interest of channeling aid through the Government of Syria alone. Notably, Russia had advanced its own draft resolution, which linked continued cross-border access through Bab al-Hawa to the establishment of a UN-led investigation into the impact of U.S. and EU sanctions in Syria. The draft failed, with the German Mission to the UN noting that it “included unacceptable language on sanctions that does not refer to core humanitarian principles.” Although the sanctions investigation was dropped from the final resolution, it may foreshadow an unwelcome confrontation for the pro-cross-border faction in the future. Proponents of the cross-border resolution now have little negotiating leverage, as they are limited to a single crossing point over which to bargain. The risk remains that Russia will seek to hold-up renewal of the cross-border resolution in 2021, and without further access points to use as a wedge, Russia is likely to seek leverage through political initiatives, such as the sanctions investigations, or to veto cross-border access altogether.

What are the stakes going forward?

Looking ahead, a multitude of operational considerations is pertinent to future access and response planning. First, the foremost concern relates to needs. German Foreign Minister Heiko Mass stated that “we cannot and do not want to conceal that we believe more crossings are necessary.” Likewise, INGOs have warned that needs gaps in northeast Syria remain unmet, following the closuring to Al Yarubiyah in January. Although some access to the northwest persists, novel gaps are likely to open as large-scale operations navigate the constraints of a more narrow response space. The foremost significance of Bab al-Hawa is as an access point to northern Idleb. Nonetheless, a reduction in access to northern Aleppo will likely create needs that may absorb aid intended for northern Idleb itself, home to the largest concentration of needs-intensive communities and camps in Syria. Altogether, the space will become more complex operationally. “Many will now not receive the help they need. Lives will be lost. Suffering will intensify,” a statement by one aid consortium noted.

Second, increased needs due to COVID-19 did not factor significantly in the debate over the cross-border resolution. This dashes the hopes of the international community and response actors who had sought to use the coronavirus pandemic as justification for greater humanitarian access. This outcome should douse expectations that expanded access can be negotiated in the face of rising future needs, such as large-scale displacement due resumed military activities or an outbreak of the coronavirus that many fear will vitiate northwest Syria’s camps. Worryingly, northwest Syria recorded its first confirmed case of COVID-19 only days before the resolution came to a vote.

Third, in the long term, it remains likely that the only way to reach populations in need in Syria will be through a combination of aid modalities. Donors will need to scale their approach to programming and geographic priorities. This will require re-balancing access through UN cross-border aid, cross-border INGOs, Damascus-based INGOs, and local NGOs. It is now abundantly clear that cross-border access alone is neither sufficient nor tenable in the long term.

Fourth, the resolution initiates a countdown for northwest Syria as a whole. In effect, Russia is believed to act on behalf of Turkey on Syria-related measures at the UN Security Council. In that respect, Turkey retains an interest in meeting humanitarian needs in northern Idleb, as failing to do so risks triggering a mass humanitarian displacement across its southern border. Re-authorizing cross-border access to northern Idleb will in part stabilize those areas. However, Russia is unlikely to relent in its persistent demand that Turkey address the presence of Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS) in Idleb. If there is a quid-pro-quo between Russia and Turkey concerning the northwest, the guarantee of continued cross-border humanitarian access may be conditioned upon Turkey’s commitment to deal with HTS. Such a reality may catalyze further violence that will have unpredictable adverse consequences for the region.

Whole of Syria Review

1. Cash crash sparks labor unrest across Syria

Tensions between longshoremen and Russia firm at Tartous port

On 4 July, local media sources reported that labor tensions have resurfaced between workers at the port of Tartous and STG Engineering, the Russian firm that operates the port. Writing in the Government-affiliated Al-Watan newspaper, Fouad Harba, the head of the Tartous port workers’ union, aired multiple grievances. Harba stated that port workers refused to collect their salaries because of the lack of data documenting salary payments. The union also objects to reductions in meal stipends provided to some workers, as well as the fact that bonuses are several months overdue, a delay the company has attributed to a malfunction in the payment processing system.

Governorate of Damascus dismisses 1,000 employees to cut costs

On 6 July, media sources reported that the Governorate of Damascus had terminated 1,000 seasonal employment contracts, culling all but an estimated 500 employees. Deputy Governor of Damascus Ahmad Al-Nabulsi stated that the employees were fired because their salaries exceeded budget allocations, following the latest wage increases. Al-Nabulsi said that “Those workers were contracted for seasonal labor during the war to help them find work in that period.” Al-Nabulsi defended the decision by stating that “there are incompetent workers among them.”

Oil field workers in Deir-ez-Zor on strike

On 6 July, media sources reported that workers at Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) controlled Al Omar, Al Tank, and Al Jafrah oil fields in rural Deir-ez-Zor governorate went on strike for several days over wage and labor disputes. Various local and media sources indicated that the workers picketed over their exclusion from the 150 percent pay raise for Self Administration employees. Now, workers have made several specific demands, among which are:

- increased wages to bring them into alignment with workers in other oil fields in Syria and neighboring countries.

- payment in dollars rather than Syrian pounds;

- improved treatment of oil field workers, and the elimination of explicitly racist hierarchies.

- protection against arbitrary dismissals; and most notably.

- establishment of a purpose-formed civil administration to manage the oil fields.

Labor action by Syrian civil society

Throughout the protracted crisis, significant labor actions in Syria have been somewhat rare events of relatively high impact. That three such events would occur, almost simultaneously, is a reflection of the degree to which economic desolation has become a flashpoint in Syria, thus triggering civic actions based on pent-up disaffection and dismal material conditions. This level of dissatisfaction is apparent in the fact that although salary payment issues are common to each of the labor actions noted above, wide-ranging grievances that touch on public administration, social conditions, and basic entitlements, have also surfaced. This is true nationwide in Syria, and it will likely grow in significance over time.

Of particular interest for the international community is the three-dimensional relationship between labor, the private Russian firm that operates Tartous port, and the Government of Syria. Under the terms of the port lease, STG Engineering captures 25 percent of port profits. There is a great deal of uncertainty concerning legal frameworks, yet the contract itself may be in conflict with investment law No. 67 (2002), while the labor practices of STG Engineering may breach the terms of labor law No. 17 (2020), which nominally guarantees port workers’ jobs despite the port’s management by a foreign private firm. Labor relations are already strained as a result of previous labor disputes at the port. Moreover, as with past breaches of contract by another Russian firm in Syria — the company controlling the Homs phosphate factory — the dispute over contracting in Tartous raises the prospect that the Government of Syria is unwilling or unable to safeguard Syrian workers’ interests when those workers are locked in a contest with private international firms seeking to extract value from high-risk ventures in Syria. In fact, Damascus’s hands-off approach, despite apparent violations of labor and investment laws, may be an implicit condition for private corporate involvement in Syria. As a result, workers may be compelled to advocate with corporate interests directly.

As for state employment, labor issues in Syria will likely increase in significance as Syria faces stronger economic headwinds. This sets up a confrontation between bloated state bureaucracies and workers. Sinecure positions in inefficient state institutions have been a mainstay of the Syrian labor landscape since the evolution of the modern Syrian state. The abundance of such positions has placed a hard floor under many Syrians who might otherwise have faced limited labor opportunities in the small private laborforce. The deterioration of state salaries has effectively shattered this reality, and the collapse of state institutions will likely accelerate the drive to eliminate workers whom central authorities are likely to view as redundant and a drain on dwindling state resources. As hardship increases and living conditions deteriorate, there is a distinct possibility that labor action will become more pronounced in Syrian civil society, particularly if labor movements can sustain a nominally apolitical image. This advancement may increase the utility of such action as a vehicle of popular dissent that is not overtly hostile to highly sensitive central authorities. If labor action can walk this fine line, it may persist as a vector of important change in Syrian civil society.

Finally, the challenges facing laborers in northeast Syria’s oil fields are somewhat unique. Local administrative bodies linked to the Self Administration have long faced challenges to their popular legitimacy. While the Self Administration is certainly the most responsive and bottom-up administrative polity in Syria, it has repeatedly failed to calm tensions that exist between its ground-level functionaries and the local population, especially in Deir-ez-Zor. Confrontations have arisen over perceived ethnic and tribal discrimination, yet analysts have been less observant of the material drivers of conflict in the area. Re-aligning salaries, as demanded by picketing workers, will be one achievable step to mitigate tensions. Restructuring the local administrative apparatus to the satisfaction of workers is less likely. As such, tensions can be expected to persist.

2. Electricity trade and smuggling highlight Syria-Lebanon linkages

Zabadani, Rural Damascus Governorate: On 6 July, local media sources reported that an unofficial border crossing from Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley to Zabadani in Rural Damascus had returned to service, following recent rehabilitation. Reportedly, the road was only recently paved for civilian use, after having served primarily as a crossing for Hezbollah forces and cross-border smuggling. Linkages between Lebanon and Syria have taken on particular significance as Lebanon sinks deeper into its economic death spiral. As the Lebanese state has collapsed financially, consumer goods have become scarce, and state services — most notably, electricity — have disappeared. The near-complete withdrawal of state-supplied power has left the country almost entirely reliant upon private generators. Although Lebanon does have an agreement to purchase electricity from Syria, there is a widespread belief that the Caesar sanctions would prohibit Lebanon from seeking additional power capacity from Syria. In public remarks last week, U.S. Special Envoy to Syria Joel Rayburn effectively ruled out this possibility. Rayburn stated that “electricity from the Assad regime is not going to save the Lebanese electricity sector.”

For good or ill, Syria and Lebanon are inextricably interlinked

The events highlight that it will likely be functionally impossible to disentangle Lebanon and Syria as both countries set off on worrying, though divergent, trajectories. As a result, policies intended to bring about change in Damascus will have inevitable fallout in Beirut, and vice versa. While cross-border smuggling between Lebanon and Syria is nothing new, the contraction of Syria’s licit economy is expected to concentrate economic activities in the hands of war economy actors, racketeers, and smugglers. These malign actors will step up to fill the gaps that open as a result of Syria’s international isolation (see: Cash crash: Syria’s economic collapse and the fragmentation of the state). Both Lebanon and Syria are anticipated to adapt to these realities and feel their consequences. The case of electricity-sharing is especially pertinent in terms of its negative implications for both countries. Lebanon’s state power company, Electricité du Liban, reportedly purchased $80 million of electricity from Syria in 2017, although the value of the sales shrank to $2 million in 2018. Figures for 2019 are not readily available. For Lebanon, the inability to source power from Syria will impose considerable hardship on the civilian population. For Syria, severing this relationship will likely cut off a supply of much-needed dollars. In both instances, further knock-on effects are likely to increase hardships on multiple levels.

3. Russian wheat deal highlights food insecurity with no solution in sight

Damascus: On 7 July, local media reported that the Syrian Grains Establishment, commonly known as Hoboub, signed an agreement with Russia to import 200,000 tons of wheat. The head of Hoboub, Yousef Qasem, was quoted as saying that Syria is currently preparing two international bids for 400,000 tons of additional wheat to shore up Syria’s reserves next year. The agreement for Russian wheat is notable in that it follows Moscow’s announcement that it would halt foreign grain sales due to food security concerns amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Food fight

The need for foreign wheat is ultimately a result of fragmented control over Syria’s wheat-producing regions. The most hotly contested arena in this respect is the northeast Syria bread basket. An estimated three-quarters of Syria’s wheat crop is grown in areas under the control of the Self Administration. The latest harvest witnessed the Self Administration’s most intense efforts to outmaneuver the Government of Syria and corner the grain market (see: Syria Update 8 June). This strategy appears to have succeeded. Local sources indicate that after initially barring farmers from selling wheat to the Government of Syria, the Self Administration has, in recent weeks, gradually relaxed restrictions on cross-line wheat sales, thus suggesting it has fulfilled its needs.

For the Government of Syria, signing a foreign wheat contract is only half the battle. The import agreements that are needed to plug gaps left by diminished production domestically have repeatedly collapsed as a result of financing challenges. These challenges are likely to persist due to Syria’s totalizing financial destitution. FAO estimates that Syria’s overall wheat production is between 2.1-2.4 million tons, far from the reported consumption of 4 million tons. While Syria’s internal grain markets are characterized by fuzzy math and contradictory estimates, the risk of food insecurity is both tangible and worrying. In the past six months alone, the number of Syrians who are food insecure rose from 7.9 to 9.3 million, according to WFP. Unless the Government of Syria can work out its balance of payments and acquire further grains from abroad, conditions will worsen.

4. New decree forces returnees to hand over hard currency

Damascus: On 7 July, Syrian Prime Minister Hussein Arnous issued a legal decree that requires all Syrians returning from abroad to “exchange 100 U.S. dollars, or its equivalent in a foreign currency that is accepted by the Central Bank of Syria.” The new policy requires that exchange will be transacted at the official Central Bank rate, recently revised to 1,250 SYP/USD. The order exempts returnees under 18 years of age and drivers of public transport vehicles.

Another push factor

Since the onset of serious fiscal woes in mid-2019, the Government of Syria has resorted to cash-grabs that have become progressively more desperate. Some of these measures have taken the form of direct cash injections. Last fall, the Central Bank reportedly convened a meeting to force Syria’s wealthiest businessmen to make large deposits, while at various times, it has also offered high-yield certificates of deposit to incentivize dollar injections by retail depositors. Other measures have sought to control the inflow of foreign capital and remittances. The most notable is a series of progressive restrictions on hawalas. Perversely, the Government’s own attempts to control currency inflows and enforce an unfavorable exchange rate are among the most significant factors in reducing foreign remittances. As a result, many Syrians have avoided traditional money transfers and have resorted to carrying hard currency across the border. By forcing returnees to convert cash at approximately half its actual market value, the state is laying claim to needed dollars, and it is adding further insult to injury for Syrian returnees. As economic conditions worsen in countries of displacement, many Syrians may be left with little choice but to return, whatever the mounting costs.

5. High-level Russian, Kurdish meeting over SDF-Russian cooperation

Ein Issa, Ar-Raqqa Governorate: On 7 July, local media sources reported that Russian military commander Alexander Chayko and SDF commander Mazloum Abdi agreed to increase Russia-SDF military cooperation following a meeting in Ein Issa. According to a statement by Abdi, subjects discussed at the meeting included Turkey’s violations of the 22 October agreement that froze frontlines created by Operation Peace Spring, as well as the killing of three female Kurdish activists in Kobani. However, it is important to note that the meeting comes against the backdrop of the latest trilateral summit on Syria involving Russia, Turkey, and Iran. Although hard details of the agreements reached at the summit — if any — are impossible to confirm, rumors have circulated that its outcomes grant scope for further tit-for-tat military operations in northeast Syria, following Turkish acquiescence of limited Government advances in Idleb (see: ‘Land Swaps’: Russian-Turkish Territorial Exchanges in Northern Syria).

Tensions rise, power struggle endures

The meeting between Chayko and Abdi should be viewed as part of a long-running campaign by Russia to constrain the breakaway ambitions of the Self Administration. To achieve this, Russia has sought to peel the SDF away from the U.S.-led international coalition and into the Russian sphere through pragmatic overtures rooted in Russia’s seemingly permanent standing in Syria. Whether such efforts will succeed in the long term will probably be determined, in large part, by the actions of Turkey. Operation Peace Spring made clear that under the current administration, U.S. objectives in Syria concern ISIS and, to a lesser extent, the twin concerns of Iran and Damascus. When push comes to shove, the U.S. is likely to value its global alliance with Turkey more highly than its tactical partnership with the SDF. Russia is sure to attempt to exploit this reality. Whether it will find new opportunities to do so as the result of renewed Turkish military operations in Ain al-Arab (Kobani), or elsewhere in northeast Syria, remains to be seen. For now, tensions remain fraught between Turkey and the SDF, and clashes continue on frontlines between the actors (see: Syria Update 6 July). While the Russian-SDF meeting is nothing new, it is a reminder that Russia is looking to exploit any crack that may open as a result of faltering commitment to northeast Syria on the part of the international coalition.

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below.

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

Is racism part of our reluctance to localise humanitarian action?

What Does it Say? The article argues that humanitarian actors are reluctant to hand over operational autonomy and funding to local actors, in part, due to system issues related to racialized ideology.

Reading Between the Lines: Aid actors and funders alike must recognize the unequal power dynamics that govern their activities. One means of breaking through these realities will be through development of better mechanisms of accountability and more thorough contextual awareness.

Source: Humanitarian practice Network

Language: English

Date: 5 June 2020

Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic

What Does it Say? The report details conflict incidents in Idleb between 1 November 2019 and 1 June 2020.

Reading Between the Lines: Both the HTS and the Government of Syria stand accused of engaging in unlawful acts and even war crimes. As always, while documentation in Syria is robust, accountability is wanting.

Source: UN Human Rights Council

Language: English

Date: 7 July 2020

What Does it Say? Remittances have long been one of the key components supporting many families inside Syria, yet recent efforts to shore-up the Central Bank have curtailed the flow of these life-saving funds.

Reading Between the Lines: As the inflow of remittances wanes, many families in Syria will find themselves in a position of greater reliance upon aid organizations and the Government of Syria for survival and basic needs.

Source: Synaps

Language: English

Date: 8 July 2020

State Institutions and Regime Networks as Service Providers in Syria

What Does it Say? The situation in Syria has severely hampered the Government’s ability to provide adequate services to its population, leading to the Government prioritizing areas under its control while imposing strict security measures on areas outside its authority.

Reading Between the Lines: The Syria system is marred by inequitable service provision rooted in authoritarian clientelism. Undoing the injustices caused by this disposition will require foreign actors to play a greater role, rather than retreating in the face of daunting realities.

Source: European University Institute

Language: English

Date: June 2020

The Fragile Status Quo in Northeast Syria

What Does it Say? Turkey’s Operation Peace Spring and the partial U.S. pull-out of the northeast have locked-in a precarious status quo for the Self Administration.

Reading Between the Lines: For the moment, the Self Administration remains in a fragile holding position, yet there are clear indicators that it cannot remain in this position indefinitely. Radical changes to the northeast are possible.

Source: The Washington

Language: English

Date: 1 July 2020

What Does it Say? Heavy gunfire was reportedly heard near the Air Force Intelligence checkpoint in the town of Karak in eastern Dar’a.

Reading Between the Lines: The situation in southern Syria remains tense, and while it is clear that many residents in the south are unhappy with the Government of Syria, Russia’s efforts to neutralize the threat posed by southern Syria’s former opposition fighters by mobilizing them under its own command have not yet succeeded in quelling the unrest.

Source: Halab Today

Language: Arabic

Date: 7 July 2020

What Does it Say? While reconstruction efforts are underway, no alternative housing will be provided for the residents of the Yarmouk and Qaboun camps

Reading Between the Lines: As we noted last week, the residents of Yarmuk are unlikely to reap the benefits of redevelopment in the long term. This announcement makes clear that they are also likely to suffer the consequences of displacement in the near term as well.

Source: Al Iqtisadi

Language: Arabic

Date: 7 July 2020

The Wartime and Post-Conflict Syria project (WPCS) is funded by the European Union and implemented through a partnership between the European University Institute (Middle East Directions Programme) and the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR). WPCS will provide operational and strategic analysis to policymakers and programmers concerning prospects, challenges, trends, and policy options with respect to a conflict and post-conflict Syria. WPCS also aims to stimulate new approaches and policy responses to the Syrian conflict through a regular dialogue between researchers, policymakers and donors, and implementers, as well as to build a new network of Syrian researchers that will contribute to research informing international policy and practice related to their country.