Syria Update

21 September 2020

Fuel shortage, bread crisis signal state failure in Syria

In Depth Analysis

Government-held Syria is in the midst of a crippling fuel crisis — evidently triggered by an acute oil shortage — the likes of which it has not seen since spring 2019 (see: Syria Update 25 April 2019). At the time of writing, queues at fueling stations stretch several hours throughout Government of Syria areas. Amid the shortage, the black market for fuel has surged, and roads in Aleppo city are reportedly almost void of cars. In response to the shortage, on 8 September, authorities hiked public transport fares by 50 percent in Aleppo and Damascus, following similar raises in other areas. These conditions would be a cause for grave concern in the best of times. Instead, they come as daily life in Syria reaches a low point amid the onset of a bread crisis, as bakeries in the Government-held areas as far apart as Damascus and Dar’a are closing their doors due to wheat shortages. The twin crises paint a portrait of a collapsing state in which a toxic mixture of conflict conditions, desperate, reactionary government, and international isolation stand in the way of quick or easy solutions to improve conditions or vent the mounting pressures now being borne by Syria’s civilian population.

During an appearance on Syrian television, oil minister Bassam Touma blamed the shortage on the U.S. Caesar sanctions. Touma stated that the measures have forced multinational firms to distance themselves from Syria and have reduced the state’s ability to import fuel, for a combined reduction in domestic distribution capacity of some 35 percent, by Touma’s reckoning. The explanation does not hold water. Meanwhile, the head of the Baniyas refinery pinned the dip in domestic fuel markets on “necessary and undelayable maintenance works” at the refinery. However, that claim collapses under scrutiny. The public tender for the current maintenance allocates a mere $6,000 for the work — hardly the scale of a project capable of bringing a nation to its knees. Moreover, the refinery underwent maintenance as recently as 2017, contradicting officials’ claims that it had been neglected for seven years. Meanwhile, the Government’s other main refinery, in Homs, has also ceased production runs. Satellite images show that the Homs facility has been out of service since 12 September or earlier, without an explanation from officials.

As with past episodes, the true cause of the fuel shortage is likely on the supply side. As oil prices dipped with the onset of the global pandemic, producers everywhere desperately sought outlets to offload excess output. As of May, Syria reportedly had received shipments of surplus Iranian oil, yet the springtime glut followed winter shortages and it came amid severe belt-tightening of the rationing systems in Syria. This suggests that further complications persist within Syria’s production, transportation and distribution networks, on top of fundamental budgetary shortfalls. Political factors may also be in play. Presently, two Iranian tankers estimated to hold two million barrels of oil sit motionless off Syrian shores, raising questions over Iran’s willingness to go the “final mile” to complete the vital Tehran-Damascus oil supply line. Tough negotiations may be taking place behind closed doors, although the strategically vague nature of Iranian-Syrian bilateral relations means that definitive answers are unlikely to surface any time soon. In time, bilateral commercial agreements or subtle changes of tack within the Syrian state apparatus may offer some evidence over the nature of the tiff between the Syrian and Iranian regimes. Until such evidence surfaces, it will likely remain impossible to ascertain whether, let alone why, Iran has seemingly withheld its hydrocarbon support to Syria.

Whatever its cause, the shortage has already had immense consequences. Touma has assured Syrians that there will be no increase in fuel prices — or the value of subsidies. However, the public transit fare hike is a significant drain for cash-strapped consumers whose wealth is evaporating due to pound depreciation. During the last fuel crisis in spring 2019, the average public sector employee in Syria earned between $65 and $100 per month. Since then, depreciation has reduced the value of top marginal salaries in Syria to a mere $26. Rising transportation costs will eventually show up in the stick prices of foodstuffs and other necessities.

Meanwhile, the closure of bakeries risks pushing Syrians deeper into food insecurity and will force individuals to seek out alternative staples, more expensive private bakeries, or aid. The World Food Program reports that 9.3 million Syrians are food insecure, and a further 2.2 million risk sliding into hunger and poverty unless conditions improve. Left uninterrupted, Syria’s steady decline will not level off. Rather, conditions are set to worsen. State officials have attributed the bread shortage to fires that ravaged wheat fields this crop season. However, most of the fires occurred in areas outside the Syrian government’s ambit. These crops were unlikely to ever end up feeding Damascus. In truth, the Government of Syria has serially failed to cover the procurement gap by importing foreign wheat. As with oil, the blame-shifting on the part of Damascus likely shows the true depths of the state’s worrying budgetary distress (see: Syria Update 6 June).

It bears noting that foreign plots to starve the Government of Syria of resources are not entirely the product of the febrile minds of the Syrian ruling regime. The U.S. Caesar sanctions do specifically seek to block any activity that “significantly facilitates the maintenance or expansion of the Government of Syria’s domestic production of natural gas, petroleum, or petroleum products.” No doubt the sanctions bite. In the past, Iran has been forced to suspend its Syria credit line, likely in response to U.S. financial pressure on Tehran. Meanwhile, U.S. support to prop up oil production in Self-Administration areas is also likely designed to tamp down the crossline oil trade and increase the resilience of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), an explicit challenge to Damascus (see: Syria Update 17 August). Happenstance has also played a role.

The implosion of Lebanon’s financial system and the violent explosion of the Beirut port have also set Syria adrift in hostile financial markets where compliance risks prevent foreign players from meaningful transactions with most Syrian business interests. For intermediary financial institutions, Syria as a whole has a toxic aura.

Yet these are not the root causes of Syria’s economic collapse. In pre-conflict times, a bounty in wheat and oil kept Syria food-sufficient and accounted for 57 percent of export revenues, respectively. The Government of Syria now presides over a rump state that is deprived of its two most significant resources by fragmented territorial control and vast conflict damage. The manufacturing base and trade that rounded out its economic profile have been eviscerated by conflict, which has also destroyed the tax base and reduced the Syrian pound to a small fraction of its pre-conflict value. In short, Syria is economically ruined because it is physically ruined, and much of this destruction has come at the hands of the Syrian government itself. International sanctions heap misery atop an already gloomy economic picture. These punitive measures have deep collateral impacts on Syrian’s exhausted civilian population, and they do so without generating significant additional leverage (see: Syria Update 22 June). Yet Damascus’s problems are, to a large extent, of its own making.

In the end, budgetary arithmetic is an ironclad trap, and the lack of resources is becoming increasingly apparent on the ground in Syria. State service provision is eroding, and further austerity is likely (see: Syria Update 14 September). This economic decline may be a gradual, uneven, and ad-hoc process, and private sector actors, cronies, and others will fill gaps vacated by the incapacitated state. For the international community, the most pertinent challenge is to prevent further suffering among the Syrians left in the cold by the state’s collapse. Meeting these needs may have the added benefit of slowing the process by which malign actors will seek to take over functions that are the state’s proper remit (see: Beyond Checkpoints: Local Economic Gaps and the Political Economy of Syria’s Business Community). In the long term, however, meaningful, holistic relief will not come until the Syrian economy itself improves. And that will not transpire until Syria’s conflict deadlock is finally broken.

Whole of Syria Review

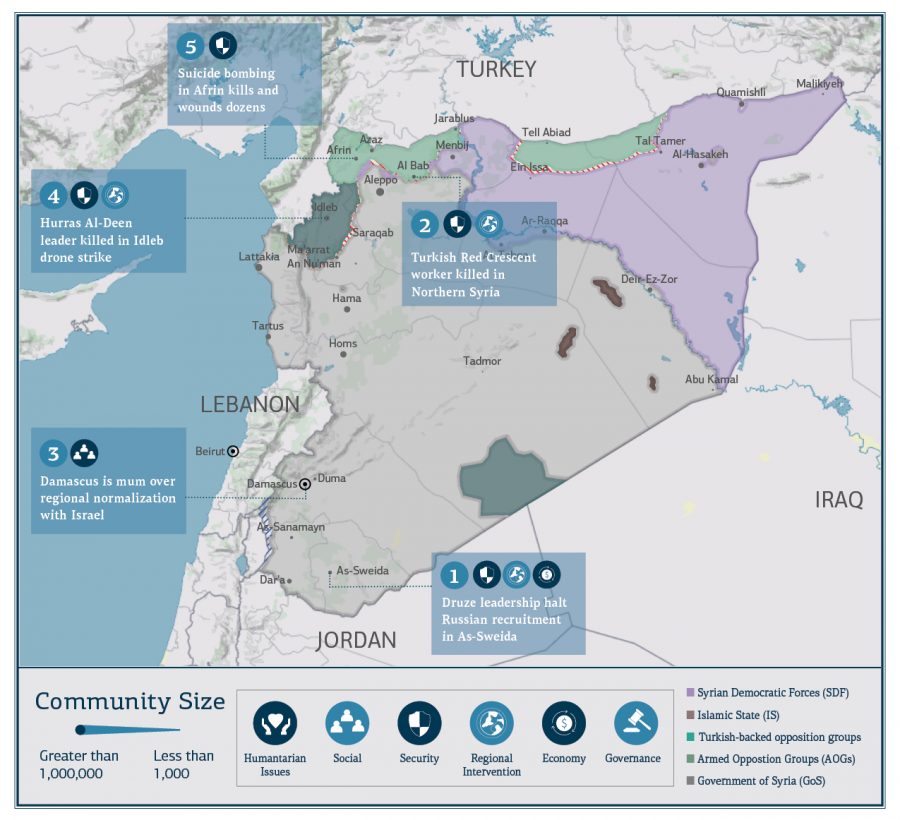

1. Druze leadership halt Russian recruitment in As-Sweida

As-Sweida: On 16 September, media sources reported that Druze leadership halted a Russian recruitment campaign seeking young men from As-Sweida willing to fight in support of Russian military interests in Libya. Reportedly, Russia was offering monthly salaries ranging between $800 and $1,500. Local sources indicate that recruitment began early this year. Due to hesitancy over the mobilization campaign, however, enlistment was limited to several dozen Druze fighters. However, upon their return from Libya following a three-month deployment, hundreds of young men are said to have signed up. Local and media sources indicated that the Druze leadership viewed the second wave of recruitment as a threat to the area’s cautiously guarded neutrality and intervened to block it.

To the shores of Tripoli

This incident in Sweida is indicative of the lure of military salaries compared with the middling livelihood opportunities available in Syria today. At current exchange rates, a Syrian public-sector worker earns the equivalent of $22 per month, meaning a mercenary recruit can bring home as much in one month of Libyan combat as in nearly four years of working for the Syrian state. These reports also shed light on another tension in the area facing Druze leadership, whose legitimacy has come in part by deliberately charting a neutral course through the conflict. Blocking Russian military recruitment may help maintain that neutrality, but it does so at the risk of antagonizing their social base, which, like all Syria, is in dire economic distress. Finally, the events also highlight that Russia may be willing to expand the 5th Corps recruitment model. The Russian-aligned 5th Corps grew rapidly following the collapse of the southern Syrian opposition, when it resolved two cardinal needs by providing a vehicle for the reconciliation of former opposition combatants and by giving Russia direct military influence in the south. Recruitment in Sweida may be evidence of Russia’s desire to employ similar tactics in As-Sweida, where popular social unrest remains a risk (see: Syria Update 15 June).

2. Turkish Red Crescent worker killed in Northern Syria

Al Bab, Aleppo governorate: On 14 September, media sources reported that a Turkish Red Crescent worker was killed and two others were wounded in an armed attack by masked assailants on their clearly marked vehicle in northern rural Aleppo, east of Al Bab. Turkey’s minister of defense has stated that all measures, including ground and air, will be taken to capture the people responsible for attacking an aid organization under the protection of international law.

Absent law, disorder is abundant

Any attack on aid workers in Syria is cause for concern, yet the conditions that underlie the incident raise further worrying questions about the stability of Turkish-held northern Aleppo. At face value, the incident highlights the general fluidity of security conditions in the Turkish-controlled regions of northern Syria, where deadly attacks claimed by ISIS continue to take place. However, Turkey’s belligerent response to the event suggests that it suspects — or would like to suggest — that Kurdish partisans are behind the attack. The Turkish Red Crescent’s popular image in Syria cannot be divorced from local sentiment regarding Turkey itself. At present, however, there is no evidence to definitively link the attack to any conflict actor, while local disputes, economic motivations, and other mundane factors cannot be ruled out with certainty.

In general, northern Aleppo also continues to witness armed attacks and bombings widely believed to be the work of Kurdish forces resentful of Turkey’s role in administering the area. This grievance has festered since the Turkish-supported takeover of Afrin (see: Northern Corridor Needs Oriented Strategic Area Profile). As such, Turkey faces a very real barrier to pacifying the area and acquiring the complete acceptance of the local population, despite the generally positive economic impact of its efforts to link portions of northern Syria into Turkish service and administrative networks. While much of the population has benefitted from nascent development at the hands of Turkey, the alienation of the Kurdish population is a barrier may indeed be insurmountable, given the intense mutual antagonism that persists. Overall, the event is a reminder that aid workers will not be spared the consequences of localized instability and unresolved drivers of conflict.

3.Damascus is mum over regional normalization with Israel

Damascus: On 15 September, media sources reported that Bahrain joined the U.A.E. in signing a formal agreement to normalize relations with Israel. Despite effulgent praise from the White House, Palestinians — including those living as refugees in neighboring states — condemned the deals as a betrayal by the wealthy Gulf Arab states. Of note, the Government of Syria has been silent regarding the deals, despite the continuing hostility between Syria and Israel, which occupies and has claimed to have annexed the Syrian Golan Heights, captured militarily in 1967.

For Damascus, opposition to Israel does not mean support for Palestinians

It is dangerous to read too deeply into the Government of Syria’s silence on the regional normalization push, particularly given Damascus’s urgent need to fight political, economic, public health, and military battles. However, condemning the move would be low-hanging fruit for Damascus, which nonetheless has several important sensitivities around the issue. Most notably, its silence may reflect a keenness to avoid rattling the Arab Gulf, which Damascus views as a likely source of needed foreign investment and reconstruction assistance. In particular, the U.A.E. is among the few nations to have open diplomatic relations with Damascus, making it one of the few nations Syria can ill-afford to antagonize. At the same time, although Syria has historically positioned itself as a defender of Palestinian rights, the Government of Syria also has a jaundiced view of Palestinian refugees inside Syria. This position is visible both in the progressive restrictions on the rights of successive waves of Palestinian refugees to Syria, as well as more recent antagonisms that have developed over the conflict. Many Palestinians bristled at their treatment in Syria and sided with the armed opposition. The Syrian government’s punitive reconstruction plans for Yarmuk demonstrate its willingness to exact harsh punitive measures (see: Syria Update 17 August). Such actions will only strain the relationship further, and they create additional sensitivity for the international response, which will be instrumental in covering gaps in services that make Palestinian refugees among the most disadvantaged groups in Syria.

4. Hurras Al-Deen leader killed in Idleb drone strike

Idleb: On 16 September, media sources reported that Hurras Al-Deen commander Sayyaf al-Tunisi was killed in a drone strike in rural Idleb, along with a second Tunisian foreign fighters. Images of the attack’s aftermath indicate that Al-Tunisi was killed by a so-called “ninja” type missile, which uses a series of blades rather than conventional ordnance. It was the same type of weapon used in previous U.S. drone strikes in Syria and the killing of Qassem Soleimani earlier this year (see: Syria Update 6 January). Al-Tunisi was previously a prominent commander in Jabhat al-Nusra, a Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham precursor, before he parted with the group following the massacre of Druze civilians in Qalb Lozeh village. Al-Tunisi later joined Hurras Al-Deen, a group linked to Al-Qaeda, which has previously been targeted in U.S. drone strikes in northwest Syria.

Mission creep

The incident highlights the peculiar reality that the U.S. presence in Syria lacks a clear and coherent strategy, amid the pursuit of multiple, seemingly unrelated types of actions. When the history of direct U.S. military involvement in Syria is written, it may well read: U.S. forces came to fight ISIS, they stayed to contain Iran, and they refused to leave in hopes of confronting Russia. Indeed, the recent deployment of additional U.S. armor to Syria in response to run-ins with Russian forces in northeast Syria is a signifier of the degree to which U.S. military priorities in Syria are a constantly moving target, and will likely continue to change in response to new conditions on the ground. For the foreseeable future, some aspect of each U.S. military priority is likely to persist. Counterterrorism operations, including drone strikes against terror suspects, will almost certainly continue, irrespective of the U.S. ground presence in the country. Likewise, the U.S. is likely to hold onto its base near Al-Tanf due to its importance in cutting off the Damascus-Baghdad highway, which lends it importance within a broader regional policy to contain Iran. For the international Syria response, it is therefore important to recognize that among U.S. actions in Syria, the troop presence east of the Euphrates River is the most tenuous, and major political events such as the unity talks among Syrian Kurds may disrupt current conditions. As such, the deployment of additional forces to northeast Syria should not be seen as a definitive proof that the U.S. intends to plant its flag in Al-Hasakeh for the long haul.

Rather, it is posturing against a geopolitical rival, and it should be seen as further evidence that in the absence of a long-term strategy, U.S. priorities in Syria can change rapidly. This is particularly true in a climate of domestic political upset. It behooves programmers to plan accordingly.

5. Suicide bombing in Afrin kills and wounds dozens

Afrin, Aleppo governorate: On 15 September, media and local sources reported that a suicide bombing killed 12 people and wounded at least 18 others in the northern Aleppo city of Afrin. Media sources suggest that the bombing bore the signature of an ISIS attack. However, local sources caution that no actor has laid claim to the incident thus far. Inevitably, local rumors also cast doubt on the attribution and point instead to the People’s Protection Units (YPG), which have been blamed for attacks in the area, where a predominantly Kurdish population was displaced by the Turkish-led Olive Branch operation in 2018.

The vicious cycle of violence and instability

The details surrounding the explosion in Afrin are hazy at best. There is still no clear indication of who was behind the incident or why. The more important concern for aid actors and the international response is what this incident indicates about the region itself. On that score, the bombing shows a continual state of instability and a lack of security. Afrin has not been a priority area for aid programming, in part because Afrin was spared intense fighting. More important yet are concerns over population transfer and the expropriation of properties. Nonetheless, the international Syria response must be aware of the events that take place in Afrin. The blast throws light on Turkey’s inability to stabilize the region, while the simmering tensions between Kurdish forces and armed groups backed by Turkey are likely to spike in the event of provocations, including the possibility of armed offensives led by Turkey in northeast Syria.

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below.

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

What Does It Say? The UN Commission of Inquiry on Syria revealed in its report that continued violations occur at the hands of nearly all major conflict actors in the country.

Reading Between the Lines: With abuse taking place across rank, file, alliance, and faction, a return to normalcy and the restoration of rule of law will be needed to halt abuses in Syria. This remains unlikely until there is an end to the most intense conflict conditions themselves.

Source: OHCHR

Language: English

Date: 15 September 2020

Remarks at a UN Security Council Briefing on the Humanitarian Situation in Syria (via VTC)

What Does It Say? As per usual, the U.S. laid blame for the difficulties of the Syria response at the feet of the Government of Syria.

Reading Between the Lines: Damascus bears considerable responsibility for the conditions in the country, including the consequences of its interference in aid delivery. However, the Government of Syria is unlikely to change its approach, and recognizing this reality does not relieve the international community of the imperative to find new ways to meet urgent humanitarian needs.

Source: United States Mission to the United Nations

Language: English

Date: 16 September 2020

Counter Terrorism Designations; Iran/Cyber-related Designations

What Does It Say? The article contains a list of people added to the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC)’s specially designated persons and blocked persons (SDN) list.

Reading Between the Lines: The U.S. continues to prosecute its maximum pressure campaign against Iran. Syrian and Lebanese entities are increasingly being named as targets in these sanctions designations, which will have an economic impact on both countries and complicate the aid environment.

Source: U.S. Department of the Treasury

Language: English

Date: 17 September 2020

Kata’ib Khattab al-Shishani: Fact or fiction?

What Does It Say? While Chechnya has been mythologized as a source of foreign fighters, this stream has been at a low ebb in recent years. The allegedly Chechen group — Kata’ib Khattab al-Shishani — has arisen recently, and appears to be making an impact.

Reading Between the Lines: There The group’s potential to make a significant impact on the trajectory of the conflict in northwest Syria is belied by uncertainty surrounding its actual origins. The possibility remains that its alleged Chechen roots are a ruse, while the actual perpetrators of the attacks it regularly claims may be other actors entirely.

Source: Middle East Institute

Language: English

Date: 16 September 2020

Quwat al-Nukhba of the 313 Force

What Does It Say? The Quwat al-Nukhba group is a special division of the 313 Force with a mandate that describes its fighters as ”mujahideen of the first rank.” It appears that its primary mission is assault operations or support, although it has also been involved in efforts to extinguish wildfires.

Reading Between the Lines: The use of combat forces for firefighting is a sign of the degree to which Syria is militarized. While it is not uncommon for military or national guard forces to contribute to large firefighting efforts elsewhere, the deployment of ostensibly elite forces for this task is a sign of Syria’s status as a nation engaged in total war.

Source: Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi Blog

Language: English

Date: 15 September 2020

For the first time, a regime government statement includes a reference to the transition of power

What Does It Say? For the first time, the Government of Syria made an explicit reference to the transition of power in Syria, through a vague clause to be presented to the People’s Assembly for approval.

Reading Between the Lines: At face value, the clause appears to be a step towards the peaceful transition of power that the international community clings to as a precondition to reengagement with Syria. However, as is so often the case in insular Syria, the likely purpose of the measure is to give the appearance of fairness. The fact remains that Bashar al-Assad is unlikely to step away from power willingly, given the dim prospects for quiet retirement among hereditary autocrats.

Source: Eqtisad

Language: Arabic

Date: 15 September 2020

Damascus recognizes the impact of Washington’s sanctions

What Does It Say? The Government of Syria has acknowledged the impact of the Caesar Sanctions, particularly on fuel. The Minister of Oil has stated that Syria is suffering from a shortage of gasoline.

Reading Between the Lines: While this may be viewed as a win by the U.S. in the maximum pressure campaign on the Syrian government, in reality it hits citizens the hardest. As the Syrian government has shown time and again, the hard impact of sanctions on the civilian population is unlikely to change the government’s stance toward the West.

Source: Asharq Al-Awsat

Language: Arabic

Date: 18 September 2020

The regime has resumed Damascus International Airport

What Does It Say? The Government of Syria has reopened its airport for roundtrips after several months’ closure due to COVID-19. The COVID-19 test fee has also been waived for incoming travelers via a statement declaring a test in the country of departure would be sufficient.

Reading Between the Lines: Reopening the airport, and changes in COVID-19 testing requirements, are likely an attempt by the Government of Syria to downplay the virus and incentivize further external travel in a bid to boost external access to the outside world.

Source: Eqtisad

Language: Arabic

Date: 17 September 2020

The Wartime and Post-Conflict Syria project (WPCS) is funded by the European Union and implemented through a partnership between the European University Institute (Middle East Directions Programme) and the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR). WPCS will provide operational and strategic analysis to policymakers and programmers concerning prospects, challenges, trends, and policy options with respect to a conflict and post-conflict Syria. WPCS also aims to stimulate new approaches and policy responses to the Syrian conflict through a regular dialogue between researchers, policymakers and donors, and implementers, as well as to build a new network of Syrian researchers that will contribute to research informing international policy and practice related to their country.