Syria Update

12 October 2020

Self-Administration vows to empty Al-Hol camp

In Depth Analysis

On 5 October, the Syrian Democratic Council (SDC), the political arm of the Self-Administration, declared its intention to clear and release all the Syrian families now sheltering at Al-Hol camp. The move will affect tens of thousands of camp residents — if it is carried out as promised. The reported first phase of releases will focus exclusively on Syrians from areas now controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). Under the plan, camp residents from other areas within Syria will be released in a second phase following the creation of needed logistical mechanisms, although thorny political considerations can be expected to impede this process. Since its rapid expansion in early 2019, the camp has been an albatross around the neck of northeast Syria’s predominantly Kurdish political leadership. Since then, the Self-Administration has sustained a difficult balancing act between the security imperative it sees in vetting and holding IDPs and many residents its believes are the families of suspected ISIS fighters — Syrians and foreign nationals alike — and the financial, social, and political costs of administering the sprawling facility.

From the perspective of the international Syria response, the SDC’s declaration of its intention to clear out Al-Hol does not herald a step-change in camp management. On the contrary, the announcement should be seen as a public statement that commits the body to continue the ad-hoc procedures that are already in place. Moreover, the timeline for the maneuver remains uncertain, and there is no clear indication that resources have been allocated for the massive undertaking. That said, it is possible that the SDF will accelerate security screenings and increase the pace of releases brokered through a tribal sponsorship system that is meant to foster good-will among Arab tribesmen. Nonetheless, the plan is likely to leave large portions of the camp population in place for the foreseeable future. For instance, the SDF will continue to hold detainees who are directly affiliated with ISIS or are accused of committing criminal acts.

Furthermore, although Iraqi refugees will be allowed to leave Al-Hol, many reportedly prefer to stay in the camp out of fear of the repercussions they may face upon returning to a vindictive and hostile environment in Iraq, where the embattled state is fixated on public prosecution of ISIS affiliates. According to Ilham Ahmad, the Joint President of the SDC, any person who wishes to stay in the camp will be permitted to do so.

From the perspective of the international Syria response, the SDC’s declaration of its intention to clear out Al-Hol does not herald a step-change in camp management. On the contrary, the announcement should be seen as a public statement that commits the body to continue the ad-hoc procedures that are already in place. Moreover, the timeline for the maneuver remains uncertain, and there is no clear indication that resources have been allocated for the massive undertaking. That said, it is possible that the SDF will accelerate security screenings and increase the pace of releases brokered through a tribal sponsorship system that is meant to foster good-will among Arab tribesmen. Nonetheless, the plan is likely to leave large portions of the camp population in place for the foreseeable future. For instance, the SDF will continue to hold detainees who are directly affiliated with ISIS or are accused of committing criminal acts. Furthermore, although Iraqi refugees will be allowed to leave Al-Hol, many reportedly prefer to stay in the camp out of fear of the repercussions they may face upon returning to a vindictive and hostile environment in Iraq, where the embattled state is fixated on public prosecution of ISIS affiliates. According to Ilham Ahmad, the Joint President of the SDC, any person who wishes to stay in the camp will be permitted to do so.

What is Al-Hol camp?

Al-Hol camp was established in the 1990s to shelter Iraqi refugees following the U.S. Gulf War. It now hosts tens of thousands of IDPs who fled areas recaptured by the SDF during the battles against ISIS between 2017 and 2019. As of July 2020, approximately 65,400 (17,900 households), mainly women and children, shelter at Al-Hol. Camp residents include foreign nationals from a multitude of countries, reflecting the deep internationalization of the Syria conflict, particularly within ISIS-held territory in eastern Syria. However, Syrians and Iraqis account for 85 percent of residents, while women and children account for 94 percent of the camp population. The camp itself is divided into nine zones: zones 1, 2, and 3 house Iraqis; zones 4 and 5 host Syrian IDPs; zones 6, 7, and 8 hold the families of ISIS members who were detained following the fall of Al Bagouz, the last remaining stronghold of ISIS; and zone 9 is where non-Iraqi foreigners are held. The latter four sections are the most secure.

Releases are nothing new, but mass release is unrealistic — for now

Local sources indicate that as social pressures have built in recent months, the SDF has accelerated its efforts to release Al-Hol’s Syrian residents, many of whom hail from Arab tribes in rural Deir-ez-Zor and Ar-Raqqa. To secure the release of their kinsmen, tribal leaders submit lists of camp residents to be released under their personal sponsorship. Tribal leaders are required to vouch that released Al-Hol residents will neither join ISIS nor have active dealings with affiliates of the group. The camp administration vets individuals on a case-by-case basis before approving their release. It is believed that a large percentage of the names submitted for release are cleared unless there is evidence of direct linkages with ISIS. According to OCHA, since June 2019, more than 4,300 Syrian IDPs have been released from Al-Hol in this way, including some with alleged ISIS affiliations. Moreover, at least 1,400 foreign women and children have been repatriated to their home countries.

All told, there is little evidence to suggest that the new release plan brings with it any additional resources or new procedures to hasten the release of Al-Hol residents. Riyad Dirar, the Joint President of the SDC, has stated that all Syrian families residing in the camp would eventually be released, including family members of ISIS fighters. How and when is not clear. Dirar stressed that the SDF would continue to screen for ISIS linkages among residents and stated that the requirement for released camp residents to have a local guarantor would remain in place. Additionally, practical steps that are seemingly critical to a mass release of residents, such as resident mapping and close coordination with NGOs operating in the camp, have not been taken.

Burden and leverage

For months, the Self-Administration has groused that international aid falls short of what it needs to maintain the camp. The message has been clear: without greater support from abroad, the SDF cannot guarantee its ability to vet camp residents, prevent the escape of suspected ISIS fighters, or prevent the group’s resurgence in Syria. In that way, the Self-Administration has given the impression that Al-Hol is a major burden, but it has been quick to use the camp — along with related ISIS issues — as a point of leverage. It is unlikely to be mere coincidence that on 7 October, the SDF publicly released figures concerning the number of ISIS inmates in its network of prison facilities. Among the 19,000 detainees are a reported 12,000 Syrians, 5,000 Iraqis, and 2,000 foreigners of 55 different nationalities. The Self-Administration’s Social Justice Council announced that more than 900 ISIS members are currently being tried in its courts. The figures offer the first public glimpse at the scale of ISIS detention in northeast Syria.

Self-Administration authorities have a strong hand to play, but they are also facing imminent threats. The increase in crossline tensions in northeast Syria has given rise to fears that Turkey may sponsor yet another military operation to prise further sections of the Syria-Turkey border from the SDF at Darbasiyah or Ain Al Arab. In September, the temporary drawdown of Russian forces near Tel Tamer triggered intense clashes between the SDF and the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (see: Syria Update 28 September). The event is a reminder of how quickly northeast Syria could be inundated by fresh bouts of violence, should political calculations change. The last time major military operations took place east of the Euphrates River was in October 2019. At that time, as Turkish-backed forces bore down on SDF positions north of the M4, the SDF warned that it would be unable to fight off the incursion and hold ISIS detainees. Such threats add to the urgency of resolving the dual challenges posed by ISIS detainees and Al-Hol residents. How to process and reintegrate the tens of thousands of Al-Hol residents — primarily civilians, many of whom are children — remains a foremost consideration for the international community as well as the Self-Administration.

In the meantime, the expedited release of displaced Syrians will help the SDF make inroads to Arab tribal communities where its approach has been criticized as heavy-handed. But it will not resolve basic governance challenges and the perception that the Self-Administration has maintained its nominal authority throughout rural Deir-ez-Zor, for instance, by tolerating corruption and graft among its local Arab proxies. For the Self-Administration, significant challenges will remain, both from within and without.

Whole of Syria Review

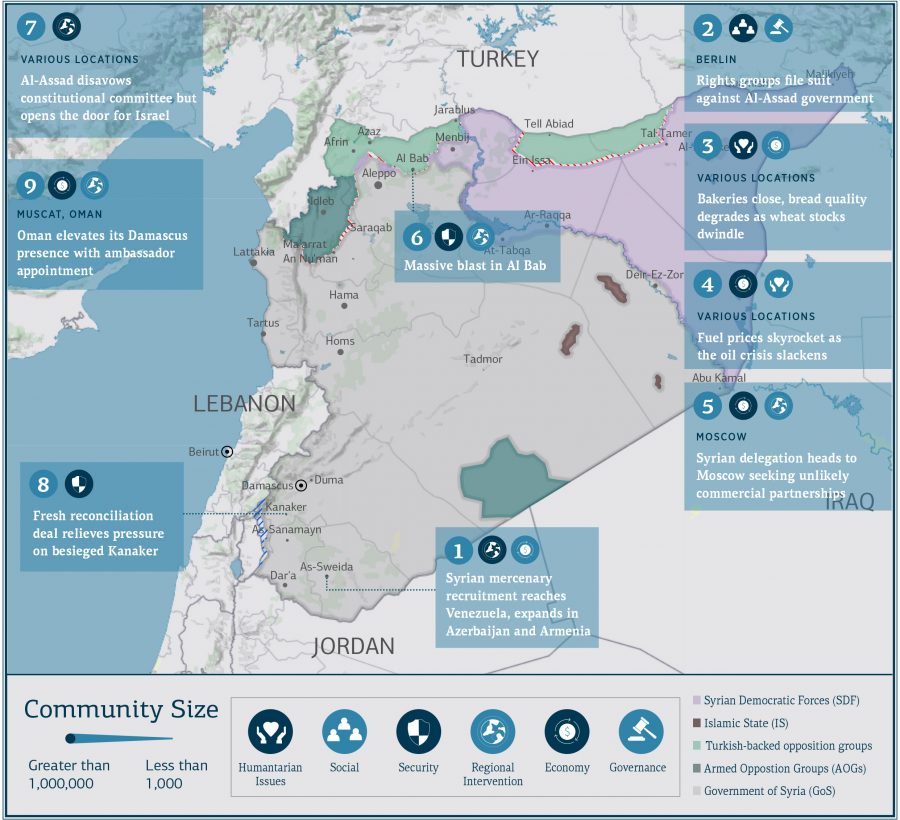

1. Syrian mercenary recruitment reaches Venezuela, expands in Azerbaijan and Armenia

As-Sweida governorate: On 4 October, local sources and Syrian media indicated that the Russian private military company Wagner Group is recruiting Syrian mercenaries to fight in Venezuela on behalf of the Caracas government headed by Nicolas Maduro. Reportedly, the deployment is intended to support Russian efforts to control local goldmines, although oil infrastructure has also been a focus of Russia’s military presence in Venezuela, which may grow due to the uncertain future of sanctions waivers for U.S. firms operating in the sector. Syrian mercenaries are being recruited from As-Sweida governorate with the promise of monthly salaries reportedly ranging between $2,500 and $5,000. As with the recruitment of Syrians for other global conflicts, the reports are unambiguous that a lack of alternate livelihoods opportunities in Syria is a significant factor for their mobilization (see: The Syrian economy at war: Armed group mobilization as livelihood and protection strategy).

The nexus of regional instability

The reports seemingly verify the lingering rumors that Syrian mercenaries have been sent to the western hemisphere for the first time, following the growing deployment of Syrians to foreign battlefields in Libya and Azerbaijan. All told, the recruitment illustrates in no uncertain terms that violence, instability, and the degradation of rule of law in Syria will have knock-on effects that are exported to other contexts. The deployment of Syrian mercenaries has accelerated in the latter half of 2020; although vast stretches of Syria are no longer active battlefields, meaningful stability is elusive. Most importantly, Syrians have diminishing hopes of realizing wage stability and sustainable livelihoods in their own shattered country. Recruitment has also proliferated because the recruiting powers, Russia and Turkey, have not faced censure. They are now able to reap the fruits of what they have sown through long-running interventions in Syria. Their reliance on Syrians as foreign fighters in other proxy conflicts has only deepened as it fuels a mad dash to man up with Syrian mercenaries. Turkey’s decision to deploy Syrians to Libya invited Russia to follow suit. The same may prove true in the Azerbaijan-Armenia conflict in the Nagorno-Karabakh region and in other contexts where both powers seek low-cost leverage.

For the international community, key considerations now revolve around the preservation of the rules-based order, the export of violence from Syria, and the country’s increasing centrality as a nexus of regional instability. Social and religious fissures in Syria will also be tested by the recruitment. The fighters being sent to Venezuela are Druze, a religious community with a sizable diaspora in Latin America, including Venezuela. The association with Russia and the Maduro government may tint fellow Syrians’ perceptions of the already maligned Druze community, which has emphatically resisted affiliating with outside powers (see: Syria Update 21 September). Reportedly, ethnic Turkmen have been deployed by Turkey to Azerbaijan, which risks generating tensions between Turkman communities and others inside Syria, particularly Kurds and Armenians, ethnic communities with tense relations with Turkey and its Syrian proxy forces. Now, ethnically Armenian Syrians (and Lebanese) have reportedly begun to deploy to Armenia in response to the flare-up in Nagorno-Karabakh.

All told, it is understood that several thousand Syrians have been recruited to foreign battlefields already. Many more are likely to follow. In a recording posted to Facebook, a Syrian mercenary in Venezuela exhorts his countrymen against deploying to Venezuela. The trip, he says, is one-way only. For a growing portion of Syria, it is a risk worth taking.

2. Rights groups file suit against Al-Assad government

Berlin: On 6 October, three organizations representing Syrian victims filed criminal complaints with the German federal public prosecutor against the Government of Syria over chemical weapons attacks, according to media reports. The grievances are the first of their kind, and they specifically target Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad “in his capacity as president of the republic and commander-in-chief, who bears ultimate responsibility for the eastern Ghouta attacks which, at the very least, could not have been executed without his knowledge,” according to Muatasim Kilani, legal director at the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression. Reportedly, further complaints will also be filed in France. The charges relate largely to the gas attack in opposition-held areas of Ghouta, rural Damascus. The Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) investigated the incident and declared that sarin gas was used, but it did not attribute the attack to any party.

The court of last resort

The filings are the most high-profile attempt by the Syrian diaspora to seek justice through the courts. In some sense, the filing reflects the reality that the Syria conflict has reached a decisive phase. The former armed opposition’s hopes of dislodging Al-Assad militarily have largely vanished. Now, other forms of resistance and resilience have taken the place of armed conflict. The cases also highlight the easily overlooked role of justice in any future settlement to the Syria conflict. The legal processes that the international community has placed in front of Syria, particularly UN Security Council Resolution 2254, give wide berth to procedural reforms and potential transition, but they do not guarantee that truth and reconciliation or justice will be achieved. In some respects, the legal proceedings are a stark reminder that in Syria, procedures that are meant to bring an end to the conflict are by no means coupled with justice, restoration of social cohesion, or redress for grievances.

3. Bakeries close, bread quality degrades as wheat stocks dwindle

Various Locations: On 8 October, local and media sources indicated that bakeries throughout much of Dar’a governorate closed due to a lack of flour. Meanwhile, local sources report that the bread that is being produced in Government-held areas is no longer soft and white, but has become brown and mealy. The unwelcome color shift is likely a result of the diminishing stocks of soft milling wheat and efforts to stretch wheat supplies by resorting to lower-quality inputs. To make matters worse, it has also been reported that the Smart Card rationing system has crashed in various locations, causing some bakeries to resort to paper vouchers that have increased wait times. Temporary relief to the pressures on Damascus may be within reach. The Self-Administration has approved the sale of 50,000 tons of wheat to the Government of Syria, local media reported on 7 October. The shipment may be enough to meet government-held Syria’s wheat needs for approximately two weeks. Reportedly, the sale price is $180 per ton, $9 million in total, although the precise terms of financing are unclear.

Grain drain

Syria’s bread crisis has hit a worrying low-water mark. Prior to the deal with the Self-Administration, local sources indicated that government-held Syria was an estimated two weeks away from widespread bakery closures and acute insecurity, although that figure cannot be independently verified. The arrival of 50,000 tons of wheat from northeast Syria will extend the time horizon, but it is doubtful that it will delay zero hour by more than two weeks. The international community should anticipate that the Syrian government will be unable to procure wheat at needed levels for the foreseeable future. Logistical challenges, financing shortfalls, and issues stemming from freight and insurance are proximate factors in the current wheat shortage, while tertiary factors such as gas and fuel shortages and rising prices have also squeezed bakeries. However, the root cause of Damascus’s wheat woes is the inability to capture more of the nation’s domestic output (see: Syria Update 8 June). On the production side, meaningful relief will come through greater trade with the Self-Administration or — less likely — the reclamation by government forces of the northeast Syria bread basket. Short of that, concerted steps to de-risk international wheat procurement may open the doors to a steadier supply of grains for Syria. Russian assistance may also be important. It has been reported that Russia is withholding wheat aid in order to pressure Damascus. Certainly, there are many bones of contention between the erstwhile allies. In the past, Moscow has stayed its hand when Damascus has soldiered on during military offensives without the Kremlin’s say-so, leading to costly battlefield setbacks for the Syrian government. However, there are clear limits to the efficacy of such a strategy, particularly when the pain it causes will be felt by ordinary Syrians rather than the ruling elite. This pressure tactic will work only insofar as Syrians’ hunger becomes a threat to the regime itself. As painful as the bread shortage may be, the Syrian populace has few means of venting rage, let alone challenging the presidential palace.

4. Fuel prices skyrocket as the oil crisis wears on

Various locations: On 7 October, the Ministry of Internal Trade and Consumer Protection raised the price of unsubsidized 95-octane fuel from 575 SYP per liter to 850 SYP, a rise of nearly 48 percent. The price of subsidized 90-octane fuel remains fixed at 250 SYP per liter. Minister of Internal Trade and Consumer Protection Talal Barazi told parliament that “the sole way to resolve the problem is for the class that owns automobiles to bear the price increase.” Local and media sources indicate that fuel availability in Syria has improved considerably since the Baniyas Refinery came back online following maintenance, although it has also been reported that a large fuel shipment from Iraq has arrived to make up for refining and supply shortfalls. Relatedly, on 5 October, media sources reported that Lebanese officials detained an oil tanker and the ship’s captain, supercargo, and other crew, who were allegedly planning to unload 4 million liters of oil to be smuggled overland to Syria. Lebanese military intelligence reportedly stated that the transfer was a violation of the U.S. Caesar sanctions.

Pain at the pump

For Damascus, raising top-tier fuel prices reduces the cost of keeping fuel tanks filled and ensuring the Syrian economy remains afloat, while largely sparing the most vulnerable segments of the population. It is not clear how or whether the supply-side shortage of oil in government-held areas in September has been fully resolved. Overland fuel trade from Iraq and Lebanon has likely been a factor in the rebound. In the long term, Lebanon’s capacity to act as Syria’s gateway to the outside oil market may change as a result of the tightening grip of international sanctions on Damascus, which are designed to deter workaround solutions hatched in Beirut. Facing pressure from Western governments and rising domestic concern over smuggling of its own subsidized fuel, the Lebanese government is getting tough on the illicit Syrian fuel trade. On 2 October, the Lebanese government announced new measures to control fuel distribution inside the country. Included are restrictions on mobility and access near the Syrian border. There is also a pervasive fear among Lebanese — viewed by some as a fait accompli — that fuel subsidies will be cut to cushion the pressure on dwindling foreign reserves. Some in government blame fuel smugglers for accelerating Lebanon’s economic collapse by selling fuel subsidized by Beirut across the border in Syria, where private consumers who cannot endure long queues or tight quotas frequently resort to the black market. Winter is fast approaching, and fuel needs will increase. It is incumbent upon the international response to plan for the likelihood that Syria will not have adequate heating fuel to last the season, and this will likely become more severe if Lebanon takes harsh restrictive measures. Winterization strategies should follow suit.

5. Syrian delegation heads to Moscow seeking unlikely commercial partnerships

Moscow: On 7 October, a high-ranking Syrian delegation met with Russian officials in Moscow to discuss bilateral economic cooperation between the two countries, Syrian media reported. The meeting focused on three sectors: energy, transportation, and water. The meeting follows a Russian delegation to Damascus in which Rusian Deputy Prime Minister Yuri Borisov touted an understanding pleading nearly 40 projects in energy, offshore oil exploration, and other sectors between the two countries (see: Syria Update 14 September). Meanwhile, in Damascus, the Union of Syrian Chambers of Trade met with Russian officials to discuss mechanisms to overcome trade barriers preventing Syrian exporters from reaching the Russian market. Reportedly, the trade file is held by the Syrian-Crimean Trade House.

Potemkin projects

Nominally, the trade talks aim to overcome barriers to Russian-Syrian commercial cooperation. In the past, such talks have failed to produce concrete outcomes, and as a rule, they ignore the most relevant barriers to bilateral trade: Syria produces little, and the country remains too unstable to sustain large-scale commercial investment. Without question, Syrian producers would leap at the opportunity to sell their wares abroad, and Russian buyers have every reason to purchase Syrian products that they could source for a kopek and retail for a ruble. Likewise, Damascus would welcome Russian investment in Syrian industry and cost-intensive vital service sectors, as would the workers who have few viable livelihoods opportunities. In reality, neither scenario is realistic under current conditions. Syria has few attractive exports, leading to the perverse reality that its gross exports are dwarfed by the value of the illicit drugs it sends overseas. At the same time, Russian investors have little appetite to countenance Syria’s instability except to stake claims to extractives and hard infrastructure. Investment in productive sectors will likely be on the back burner until Damascus can guarantee stability for foreign investors. If Damascus is waiting for a deus ex machina to relieve the pressure brought on by economic meltdown, it should not look to Moscow.

6. Massive blast in Al Bab

Al Bab, Aleppo governorate: On 6 October, a truck bomb explosion outside a bus station in Al Bab city killed 18 civilians and injured at least 75 others, according to media reports. As with past incidents in the city, no actor has claimed responsibility for the attack. The UN Resident Coordinator and Humanitarian Coordinator for Syria, Imran Riza, and Regional Humanitarian Coordinator for Syria, Kevin Kennedy, condemned the “horrific attack.” Of note, the Syrian Democratic Council issued a statement condemning “this cowardly terrorist attack,” but the Kurdish-led political body also placed blame for the incident on armed factions backed by Turkey. The statement declared, “we hold the extremist fundamentalist factions [i.e. Turkish-backed armed groups] responsible for these bombings,” noting that Kurdish officials have requested that military and security sites in the city be removed from civilian areas.

Setting the stage for instability

The massive attack puts on full display the violence being marshaled by actors seeking to destabilize Al Bab, which remains under nominal Turkish control. What is not clear is which of the various enemies of Turkey’s proxy forces is behind the attack. Ankara and Turkish-language media have been quick to lay blame at the feet of the YPG and affiliated Kurdish factions for such attacks. ISIS cells are also believed to remain active in the area, which Turkey captured in 2017, following a strategic push to head off the westward advances the SDF was then making against ISIS. The uncertainty over who has carried out these attacks is likely deliberate, and its clearest message is that armed opposition groups backed by Turkey have yet to pacify — let alone stabilize — the city they have held for nearly four years.

7. Al-Assad disavows constitutional committee but opens the door for Israel

Various Locations: On 4 October, Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad stated in a television interview with Russian network Zvezda that Damascus will not discuss issues related to Syria’s fundamental stability during the next round of Constitutional Committee talks in Geneva. Al-Assad emphasized that the constitutional demands of “other parties” supported by Turkey and the U.S. will undermine Syria — and are therefore off limits. Of note, Al-Assad also stated that the war is not over and added that the Syrian Arab Army will launch new military operations in Idleb because the Russian-Turkish deals there “are not effective.” Days later, in another interview with Russian news agency Sputnik, Al-Assad stated that Damascus is prepared to normalize relations with Israel, but only when the latter “is ready to return the occupied Syrian lands” — a reference to the Golan region.

From political transition to normalization with Israel

Some have understood Al-Assad’s remarks as a sign of a rift between Damascus and Moscow over the nature of political transition in Syria. This interpretation suggests that Al-Assad is seeking to hem in the work of the Constitutional Committee, which is the signature achievement of Russian and Turkish diplomacy in Syria to date. Whatever its outcomes, the constitutional process faces a Damascus veto. The Government of Syria bloc has the power and unity to stall proceedings in Geneva, while both Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergey Lavrov and Al-Assad have affirmed that any amendments to emerge from negotiations must be approved by the Syrian Parliament. In that respect, the 2021 presidential elections will go ahead whether or not the committee makes progress on relevant files. Little wonder that on 8 October, a group of prominent Syrian opposition figures, including Ahmad Al-Khatib, George Sabra, and Michel Kilo, issued a statement denouncing the Constitutional Committee and describing it as a “waste of time” intended to forestall indefinitely the political transition called for by UN Security Council Resolutions 2245 and 2118.

Statements concerning Syria’s relations with Israel may signal Al-Assad’s desire to cajole the international community into accepting an authoritarian peace in Syria. Al-Assad’s remarks appear to suggest a quid pro quo arrangement: relief from sanctions and Syria’s international pariah treatment in exchange for normalization with Israel. With the severity of the economic crisis and the reluctance of the U.S. and the EU to restore relations with the Government of Syria without a political transition, Damascus appears to be signaling its willingness to use normalization with Israel as a substitute for a domestic political transition. On the one hand, Al-Assad may find negotiations with Israel, potentially under Russain auspices, an effective way to break Syria’s international isolation and distract from talk over the Constitutional Committee.

On the other hand, the extent to which Iran and Hezbollah, among the most important allies of Damascus, are willing to accept such a deal is in question.

8. Fresh reconciliation deal relieves pressure on besieged Kanaker

Kanaker, Rural Damascus: On 6 October, local and media sources reported that the Government of Syria and local notables in Kanaker had reached a novel reconciliation deal. The agreement resolved an impasse in earlier negotiations to end the government’s siege of the restive community (see: Syria Update 28 September). Previously, the Government of Syria had demanded the handover of several wanted individuals and the surrender of weapons in return for lifting the siege. Notably, Damascus had set a deadline of 29 September for the community to capitulate, but it took no action when the date passed without resolution to the standoff. Local sources indicate that on 7 October, the Government of Syria and local notables from Kanaker reached the new deal stipulating the handover of 100 weapons and allowing Military Security to search homes and agricultural lands. In turn, the Government of Syria released several detained women and lifted the siege. Under the terms of the deal, no members of the community were to be forcibly displaced.

An indicator, but not a canary in the coal mine

Kanaker has been a hotspot in Rural Damascus since late 2019 (see: Syria Update 4-10 December 2019). When local tensions first erupted in the community, we noted that violence in Kanaker may be a harbinger of unrest to come in other parts of government-held Syria. Since then, anti-government protests have flared throughout southern and central Syria, but nowhere more visibly than the traditional hotbed of strident dissent, Dar’a. However, the current resolution of the Kanaker siege clarifies the need to distinguish more finely among specific drivers of unrest in the area. Like As-Sanamayn before it (see: Syria Update 27 April), the besiegement of Kanaker is an outgrowth of the uncertainty created by the community’s ambiguous reconciliation terms. This is exemplified by the Syrian government’s insistence upon taking custody of wanted individuals and securing loose weapons. Unlike As-Sanamayn, however, Kanaker has averted the need to agree to forced evacuations — at least for now. The situation in Kanaker has returned to relative calm and the detained women, whose arrest resulted in the initial protests that sparked the violence, have been released. However, it is unlikely that the situation has been resolved to the full satisfaction of Damascus, and a return to violence or besigenment is distinctly possible.

9. Oman elevates its Damascus presence with ambassador appointment

Muscat, Oman: On 5 October, Oman became the first Gulf Arab state to reinstate its ambassador to Damascus, after an 8-year intermission. The announcement follows the decisions by UAE and Bahrain to establish lower-level diplomatic ties with Syria, culminating in the reopening of their embassies in Damascus in December 2018. Although Oman withdrew its ambassador from Damascus in 2012 when Syria was suspended from the Arab League, unlike the UAE, Bahrain, and its other Gulf Cooperation Council counterparts, Oman refused to cut ties with Damascus altogether. Muscat kept its Damascus embassy open throughout the war (under the command of a charge d’affaires) and refused to publicly support the opposition. As early as 2015, Muscat invited the Syrian foreign minister to Oman, and the Omani foreign minister similarly met with Al-Assad in Damascus that same year and again in 2019. Notably, in late 2018, Al-Assad singled out Oman as being supportive of Syria.

‘Black sheep’ no longer

Oman has long positioned itself as a regional diplomatic hub, the broker of unlikely negotiations, and a champion of regional noninterference. Most notably, as the “black sheep” of the GCC, it played a crucial backchannel role for the U.S.-Iranian nuclear negotiations. With respect to Syria, Oman has walked a fine line. Although Muscat distanced itself from Damascus during the fiercest periods of the conflict, when the Syrian government was most intensely isolated, it did not sever its linkages entirely. Seen in that light, the reinstatement of Oman’s ambassador is not a watershed moment in its Syria policy. It is, rather, the culmination of a series of quiet maneuvers calibrated to keep all doors open. What separates Oman from its Gulf neighbors is the way it carries out foreign affairs — deftly and without the aggressive ideology that characterizes the polarizing approach of actors like the UAE. Like its neighbors, however, Oman is also seeking material benefits. Damascus and Muscat signed a memorandum of understanding for energy cooperation in 2017. The Caesar sanctions and international pressures will defer such ambitions, but Damascus is unlikely to forget Oman’s relative pragmatism, and the Gulf nation may hope to capitalize on its standing by serving as an important backchannel to Damascus.

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below.

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

Queerness and the revolution: Towards an alternative Syrian archive

What Does It Say? LGBTQ+ issues have not been a part of efforts to reconstruct, rebuild, pr archive Syria’s history since the start of the conflict, leading to significant gaps in understand civil society and Syria itself.

Reading Between the Lines: Frequently, issues pertaining to basic quality of life and dignity are not on the radar for those working the Syria response. Holistically integrating such concerns will be crucial to achieving a just and sustainable resolution to the conflict.

Source: Syria Untold

Language: English

Date: 29 September 2020

Syria Is Still Trying to Use Chemical Weapons

What Does It Say? The Trump administration has told Congress that the Government of Syria is still pursuing chemical weapons and missile delivery systems despite the ongoing conflict and U.S. airstrikes to destroy such facilities.

Reading Between the Lines: Whatever its basis in fact, such claims are nigh impossible to falsify, and they harken back to the precedent set by the U.S.’s invocation of chemical weapons as a precursor to support for war efforts in Iraq and in Syria itself.

Source: Foreign Policy

Language: English

Date: 6 October 2020

Assad and the Challenge of Staying Power: Five Key Obstacles

What Does It Say? Bashar Al-Assad faces many challenges when it comes to staying in power, both due to internal and external forces.

Reading Between the Lines: The Al-Assad regime does indeed face stiff resistance to its staying in power. However, Al-Assad is the apex actor in a political system designed around self-preservation. Elections are unlikely to succeed where massive external military intervention failed.

Source: Al Araby

Language: Arabic

Date: 7 October 2020

Southern Syria: ‘Sibling feud’ or engineered violence?

What Does It Say? The kidnappings occurring between Dar’a and As-Sweida are not due to Sunni-Druze tensions, but are a consequence of the economic desperation and the abundance of weapons in those areas.

Reading Between the Lines: Southern Syria will continue to be a region of complex instability and violence until there is a resolution to the conflict and living standards have improved.

Source: Middle East Institute

Language: English

Date: 7 October 2020

The Salvation Government fixes real estate rental fees in Turkish lira or dollar

What Does It Say? The Salvation Government in Idleb has set rental fees for everyone in their territory in either U.S. dollars or Turkish liras.

Reading Between the Lines: The significance of the shift is two-fold. On one level, it shows a complete lack of trust in a failing Syrian currency. On another, it illustrates the depth of Idleb’s absorption into Turkey’s economic orbit.

Source: Enab Baladi

Language: Arabic

Date: 7 October 2020

The system allows Yarmuk residents to return to their homes, but with conditions

What Does It Say? The Government of Syria has allowed Yarmuk residents to return to their homes under three conditions: safe construction conditions, proof of ownership and possession of the necessary security approvals.

Reading Between the Lines: The conditions amount to a near total dead end for many former residents of Yarmuk. Security approvals alone are likely to furnish an insurmountable barrier, thus allowing the state to exploit and commandeer prime real estate.

Source: Eqtsad

Language: Arabic

Date: 6 October 2020

The security dimension in putting pressure on Hurras Al-Din: Methods and goals

What Does It Say? Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) is undertaking operations to arrest leaders of rival factions in hopes their groups will fail and disband without strong central authority.

Reading Between the Lines: HTS has established itself as the main power in Idleb. Its ongoing arrests of faction leaders are likely an attempt to cement its standing for the future, not least by showing its willingness to take a hard line against other ‘extremist’ factions.

Source: Jusoor for Studies

Language: Arabic

Date: 7 October 2020

Syria intends to obtain the Russian vaccine against Corona

What Does It Say? Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad has stated that Syria will negotiate with Moscow to get the Russian COVID-19 vaccine, as soon as it is available. He also indicated that he would be taking the vaccine.

Reading Between the Lines: Cases continue to rise at a rapid pace in Syria, as the country seemingly hurtles toward an experiment in herd immunity. The promise may win some favor among an exhausted populace that has little hope of unified government steps to combat the virus.

Source: RT Online

Language: Arabic

Date: 7 October 2020

The Wartime and Post-Conflict Syria project (WPCS) is funded by the European Union and implemented through a partnership between the European University Institute (Middle East Directions Programme) and the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR). WPCS will provide operational and strategic analysis to policymakers and programmers concerning prospects, challenges, trends, and policy options with respect to a conflict and post-conflict Syria. WPCS also aims to stimulate new approaches and policy responses to the Syrian conflict through a regular dialogue between researchers, policymakers and donors, and implementers, as well as to build a new network of Syrian researchers that will contribute to research informing international policy and practice related to their country.