Syria Update

19 October 2020

Fire on the coast: Damascus vows support — but not much

In Depth Analysis

Devastating wildfires have ravaged the Syrian coast, consuming an estimated 9,000 hectares of olive and fruit orchards, mountain scrubland, forests, and a patchwork of communities predominantly inhabited by religious minorities. At least four people were reported killed in an estimated 156 fires that raged from 9-10 October in Lattakia, Tartous, and western Homs governorates. Altogether, approximately 140,000 people were affected through damage to homes and property, the extended loss of power and water, and severed access to services such as hospitals. Some villages were completely evacuated, and displacement rates were particularly high in Jablah, Lattakia, and Al-Qardaha, the ancestral homeland of the Al-Assad family. On 13 October, Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad made a rare public visit to Lattakia, where he toured fire-affected areas, spoke with local residents, and pledged state support. On 14 October, the first Syrian Arab Red Crescent relief convoy reached Al-Fakhoura village in rural Lattakia to deliver assistance to affected residents.

The government’s rapid response to the blazes shows the state’s willingness to aid communities often viewed as the Al-Assad regime’s base, namely Alawite co-religionists and, to a lesser extent, the Syria’s embattled Christian minority. Certainly, the relief offered to Lattakia in particular contrasts starkly with the neglect of As-Sweida, where predominantly Druze farmers were left largely to fend for themselves in the wake of fires earlier this year. This contrast is important, but it misses the forest for the trees. The blazes that laid waste to the coast have also laid bare the Syrian state’s diminishing capacity to provide needed civil defense to battle wildfires, and the social support that has been pledged is miserly. Altogether, they are evidence of the Syrian government’s shrinking capacity to cater even to its most critical power base.

Social tensions inflamed

For the international Syria response, Syrians’ reactions to the episode is indicative of the deep social cohesion challenges that will be difficult to overcome in the long term. There is a perception that the Syrian coast is largely cohesive because it has been spared the worst direct consequences of the conflict. On the contrary, the finger-pointing prompted by the wildfires highlights that the deep social divides that permeate the rest of Syria are also present in the area, notwithstanding that it is often viewed as reflexively pro-Damascus.

Allegations began to flare even before the flames died down. Some have pointed fingers at the Syrian opposition, accusing opponents of Damascus of deliberately igniting the blazes to punish the Al-Assad regime’s Alawite social base. Some have implicated predatory real estate speculators and Syria’s seemingly omnipresent business elite. Unconfirmed reports indicate that property owners have already received offers on fire-affected real estate at significantly above-market rates. The rumors have fueled a narrative that developers are seeking to exploit the catastrophe to drive a private redevelopment of the Syrian coast, as seen in conflict-affected communities throughout the country. Within Christian communities, there is also a narrative that neighboring Alawites are resorting to arson to drive Christians away from the coast, the most important redoubt of the Alawite minority.

The fires have also inflamed regional tensions. Some opposition activists have attributed them to Iranian agents, suggesting the blazes were intended to turn up the heat on Russia, which largely stood by as the wildfires raged. Russia was widely criticized for its idleness, and Syrians have pointed to reports of its firefighting assistance to Israel in 2016 and 2019 as evidence of Moscow’s indifference toward the well-being of Syrians, despite its decisive military support for Damascus.

In Syria, some communities are more equal than others

On 15 October, Lattakia Governor Ibrahim Salem announced a 1.53 billion SYP state grant ($660,000) for fire-affected villages in Lattakia governorate, with each village slated to receive 10 million SYP ($4,300). Additionally, 500 million SYP ($215,000) in interest-free loans was reportedly allocated for farmers in Lattakia to compensate for their lost crops, livestock, and agricultural lands. The support stands in marked contrast to the state’s meager response to wheat farmers in southern Syria who were left to fend for themselves following fires earlier this year. Nonetheless, the sums Damascus has promised to coastal fire victims is a token gesture that verges on being insultingly small. Despite Al-Assad’s assurance that Damascus will “bear the greatest financial burden” in helping the victims, it is difficult to imagine the superficial support will have the impact needed.

Seizing on discontent among the Alawites, disgraced businessman Rami Makhlouf pledged to donate 7 billion SYP from Syriatel’s coffers to aid those affected by the fires. Given that the firm is no longer under his control, the pledge is more accurately seen as a guttersnipe attack on Al-Assad than an earnest show of support.

If anything, the fires demonstrate the advanced decrepitude of the Syrian state. Amid shrinking budgets and worsening austerity measures, the state has increasingly sacrificed its remote appendages to concentrate diminishing resources on vital core functions. Given that the state is locked in desultory regional conflict, its foremost priority will likely remain military spending, no matter the grim arithmetic this creates for social expenditures. As we noted when smaller fires were raging along the coast in September (see: Syria Update 14 September), the state has little means of extinguishing the blazes to which Syria is susceptible. Its ability to act has been hampered further by political isolation from its neighbors and the potential for crossline support from groups like the White Helmets. To distract from its modest support to fire victims, the state and its supporters have propagated the theory that the blazes were the deliberate work of arsonists. Shifting the focus to external actors is a tried and true tactic in Damascus. But it does not obscure the reality that diminishing resources are available for these and other vital services. The dearth of resources will likely become more apparent as time goes on.

Whole of Syria Review

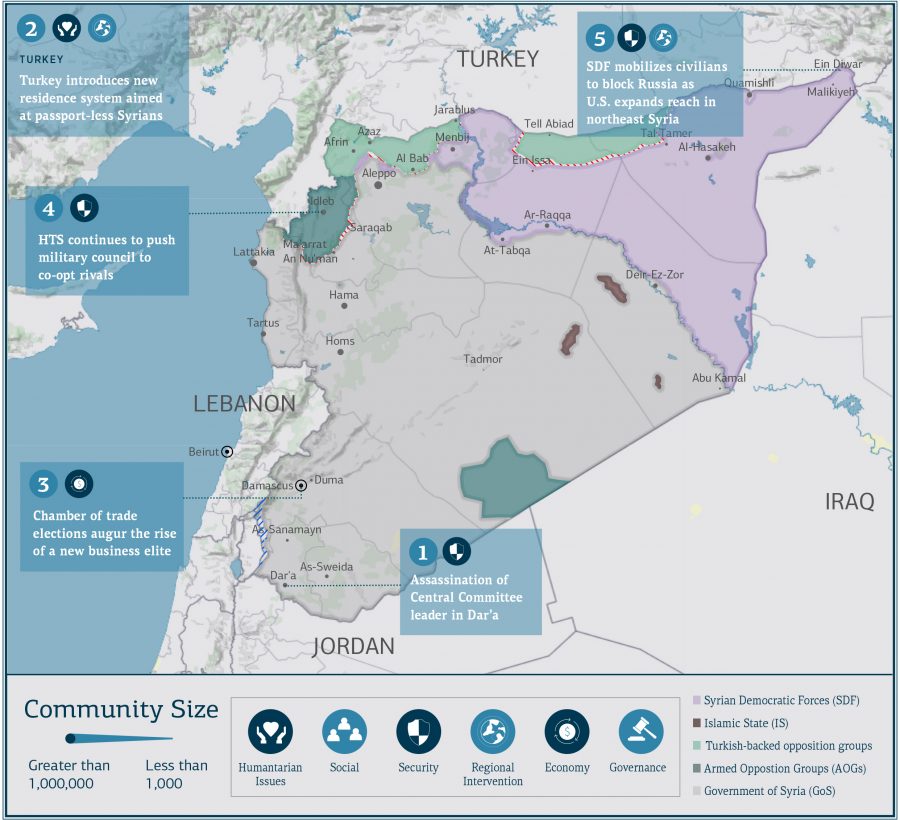

1. Assassination of Central Committee leader in Dar’a

Dar’a governorate: On 14 October, media sources reported the assassination of five former Free Syrian Army commanders in Dar’a. Among those killed was Adham Al-Krad, the former commander of the Engineering and Rocket Regiment and a prominent member of the Central Committee, a vital negotiations platform in Dar’a Al-Balad. Two other members of the Central Committee, Ahmad Mahamid and Mohammad Al-Dughaim, were also killed, as were Rateb Al-Krad, the former commander of Ahfad Al-Rasoul Brigade, and Adnan Al-Masalmeh. The commanders were targeted near As-Sanamayn as they returned from Damascus, where they had met with security figures to discuss detainees. Their vehicle was intercepted by a van of gunmen who opened fire, killing Adham Al-Krad on the spot. Brigadier-General Louay al-Ali, the Head of the Security Intelligence Branch in Dar’a, was widely accused of being responsible for the assassinations. It is worth noting that this is the first time that Al-Krad has left Dar’a governorate — and one of the few times he has left Dar’a Al-Balad — since the area’s reconciliation in July 2018. On 15 October, thousands participated in the funeral procession for Al-Krad, which started on As-Sanamayn and proceeded toward Dar’a Al-Balad. The burial then transformed into an anti-regime protest that marched from Al-Omari Mosque to the Martyrs Cemetery located south of Dar’a city.

Silencing the anti-regime voices

The assassination of Adham Al-Krad is no surprise considering the chaotic security landscape of Dar’a (see: Security Archipelago: Security Fragmentation in Dar’a Governorate), where prominent reconciled commanders remain frequent targets. Of a reported 17 individuals assassinated in Dar’a governorate in September, 14 were former opposition military leaders. Al-Krad was especially prominent, as he was among the commanders who took part in the negotiations that led to the Russian-sponsored reconciliation agreement in Dar’a in July 2018. Al-Krad has refused to subordinate Dar’a Al-Balad’s armed factions to the Russian-backed 5th Corps, although he agreed to coordinate with Russia to halt Iranian ambitions in the south. However, over the past several months, Al-Krad had taken a more hostile stance against Russia, accusing Moscow of ignoring its pledges to contain Iran and turning a blind eye to the security deterioration and overt targeting of reconciled commanders in Dar’a.

Al-Krad’s assassination bodes poorly for the future stability of southern Syria. Such incidents poison the well for negotiations between reconciled communities and Damascus. If the Syrian government cannot guarantee the security of its interlocutors, the flimsy basis for negotiations that exists today will weaken even further. Assassinations are also likely to prompt retaliation from local reconciled groups, perpetuating a cycle of violence that will potentially lead to reprisal attacks on Syrian government personnel and security and military checkpoints. However, in the long term, such incidents can also be expected to weaken the standing of reconciled communities that continue to hold out a litany of negotiating terms with Damascus. Over time, however, deliberate and systematic attacks may force a weakened opposition to admit a greater degree of Government of Syria influence in the area.

2. Turkey introduces new residence system aimed at passport-less Syrians

Turkey: On 8 October, the Turkish Directorate General of Migration announced a new type of residence permit for Syrian aid workers, the Humanitarian Residence Permit. The announcement came during a meeting between a number of Turkish officials and the Syrian Associations Platform, an informal representative body for Syrian entities operating in Turkey. The new scheme exempts applicants from providing valid passports, a major impediment to Syrians who cannot renew their Syrian passports for security or financial reasons. Syrians who hold any type of Turkish residence permits in the country — including short-term, student, and family residence permits — will be eligible for the two-year Humanitarian Residence Permit. However, holders of the Temporary Protection Card registered as refugees in Turkey will not be eligible for this new scheme, although it will apply to their children who do not possess Syrian identification documents. The Humanitarian Residence Permit will allow its holders to travel freely within Turkish provinces, although it is not clear how residence-holders will return to Turkey after traveling abroad.

The next Syria-Turkey battlefront: Bureaucracy

The new residency scheme may spare Syrians in Turkey from significant bureaucratic hurdles, including the need to revert to Government of Syria institutions to renew travel documents needed to remain in Turkey. In 2014, Turkey initiated the Temporary Protection system for Syrians who had entered the country after April 2011 as refugees. While a valid passport is not required, the scheme is fraught with restrictions. These include work and movement between Turkish provinces. These conditions have prompted many Syrians to apply for other types of residence permits, including short-term, property, and student residence permits, which are valid for one or two years and require a valid passport for renewal. As of 2018, around 48,700 Syrians obtained short-term residence permits (known locally as the Touristic Permit).

The most noted barrier in the current system is the need to procure documentation from Syrian government institutions. For the Syrian diaspora, this is a security challenge and a significant financial burden, as Damascus has increasingly utilized these systems as a source of foreign currency. Although figures differ, it has been estimated that Syrian diplomatic posts abroad collected more than $100 million in passport renewal fees between 2011 and 2018. The passport itself costs between $300 (normal track) and $800 (fast-track), with the a maximum validity of two years, on top of the security threats, mistreatment, and harassment associated with the process. Syrians often hire mediators who charge between $250 and $600 for securing an appointment for the applicant. It is worth noting that Law no. 17 of 2015 permits all Syrians to renew their passports, including those affiliated with the opposition members or left the country illegally, suggesting that Damascus is more than happy to deal with its enemies, provided there is a financial payout to doing so.

Now, Turkey’s decision to forego the need for a valid passport meets a significant demand of the Syrian diaspora and civil society organizations. For Turkey, the move is an easy win among the Syrian diaspora, and it moves one step closer to normalizing the status of the many Syrians who have been pushed into legal grey areas due to financial incapacity and security concerns. For Ankara, the fact that Damasucs may lose significant revenues in the process is icing on the cake.

3. Chamber of trade elections augur the rise of a new business elite

Damascus: Syria’s one-time industrial leaders are on the verge of being almost totally marginalized as a new crop of wartime elites win positions in chambers of commerce across Syria, according to electoral results reported in local media sources. On 9 October, Abdullah Ali Qattan, a relative unknown now under U.S. sanctions and EU restrictive measures, received the second largest share of votes for the Damascus Chamber of Commerce. Qattan is considered a favorite to assume the chairmanship. Qattan’s rise has been possible only because the top incumbents declined to seek re-election. Chairperson Muhammad Ghassan Qalaa and secretary Muhammad Hamsho both stood aside, clearing the path for Qattan, who has risen from relative obscurity and is now seen as a bag man for the Al-Assad family’s personal financial interests.

Captains of industry are out. Cronies are in.

The Damascus chamber elections echo the results in other chamber elections in recent weeks, including in Aleppo, Syria’s industrial hub. Holistically, the results show the declining relevance of industrialists within Syria’s overall economic landscape. In their place, there are new titans of trade. The transformation may presage a shifting emphasis toward the import trade and business conducted with Iran and Russia, although the means of financing such imports remains uncertain — and is a critical concern given Syria’s dwindling foreign reserves (see: Syria Update 12 October). This shift may be a pragmatic recognition of Syria’s reliance upon its closest state allies. Yet it also stands as a grim indicator of the regime’s abandonment of industrial rehabilitation and the domestic output that will be needed to contain inflation.

4. HTS continues to push military council to co-opt rivals

Idleb governorate: Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) has reportedly continued to use its influence to drive the formation of a military council to gain full control over high-level decision-making in opposition-held northwest Syria, according to local sources. The council formation reportedly includes the military commander of HTS, an Ahrar Al-Sham commander now under strong HTS control, and a military representative from Faylaq Al-Sham. A key consideration in the formation is HTS’s capacity to exploit cleavages and intensifying internal divisions within the ranks of Ahrar Al-Sham as it seeks to co-opt the group’s military command. According to local sources, the council will reportedly preside over a force consisting of 40 brigades of approximately 700 fighters each.

In parallel, HTS has continued to squeeze rival faction Huras Al-Deen. On 17 October, the HTS general security apparatus arrested two Huras Al-Deen commanders in rural Idleb governorate. The arrests come after a U.S. drone strike killed two other Huras Al-Deen commanders on 15 October.

With friends like these …

For almost two years, HTS has fought low-temperate contests with fellow opposition groups to establish itself as the unquestioned power-broker in Idleb. The group has exercised effective armed control over most of the governorate since its hostile takeover in January 2019, although its relationship with other opposition factions has remained contentious (see: Syria Update 4-9 January 2019). HTS’s frequent attempts to distance itself from — and co-opt or disband — more radical factions have alienated its erstwhile allies and its own hardline wing. Caught between the need to satisfy the competing agendas of Turkey and Russia, HTS has been set on a collision course with its rivals. In the long term, something has to give. HTS’s move to centralize control via the command room is reportedly backed by Turkey, and the move will also likely meet with approval from Moscow, which has recently hinted that HTS may not be among the radical groups it seeks to eradicate in Idleb.

Altogether, HTS’s efforts to stand up a new military council are likely one leg of a “decapitation” scheme now playing out across Idleb. The council formation may furnish the means of co-opting the leadership of rival groups in hopes that lower ranks will bow to pressure and fall in line or disband. Infighting within Ahrar Al-Sham may pave the way to such an approach. The other leg is HTS’s approach to the Al-Qaeda-linked group Huras Al-Deen, which has been weakened by HTS itself and U.S. drone strikes (see: Syria Update 21 September). However, there is little evidence that the repeated attacks have changed the fundamental conditions on the ground in Idleb, nor is it clear they have shaped the intergroup conflict — yet.

Although rumblings of the military council’s formation were heard earlier this summer, it has not yet been publicly announced. If and when this occurs, it will likely come as a decisive step toward yet another rebranding of HTS. Along the way, HTS will also have to mind its own house. Divisions within the group remain a source of instability, and Islamist infighting in northwest Syria can derail the best laid plans.

5. SDF mobilizes civilians to block Russia as U.S. expands reach in northeast Syria

Ein Diwar, Al-Hasakeh governorate: On 12 October, media sources reported that Russian forces failed for the fifth time to establish a military base in Ein Diwar, less than one kilometer south of the Turkish border in Al-Malikeyyeh district. A Russian convoy was confronted by local civilians who blocked the road and harangued the forces, ultimately compelling the convoy to retreat toward the Quamishli Airport. Reportedly, Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) galvanized the community to resist any Russian presence in the area and mobilizes on-the-ground support through SDF-affiliated local officials, including the “comins” who serve as community focal points. In the wake of the confrontation, multiple Russian patrols have circled areas surrounding Ein Diwar, but without significant effect.

In parallel, during the past two weeks, the U.S. forces have reportedly taken several concrete steps to increase their footprint in and around oil-rich areas in Al-Hasakeh and Deir-ez-Zor. Two military bases were established in the cluster of villages near Jazerat, in west rural Deir-ez-Zor and Baguz in east rural Deir-ez-Zor, while more troops and equipment were sent to both Shadadah base south of Al-Hasakeh, and Al-Omar Oil Field base north of Al Mayadin.

Local communities: secret weapon or human shield?

The U.S. and Russia harbor incompatible visions for the medium-term landscape of northeast Syria. Their capacity to realize these visions depends in no small part upon the acceptance and resistance of local communities. Throughout Syria, resident populations have frequently interrupted U.S., Russian or Turkish patrols and military convoys, often with the express or implied backing of rival military actors. Most recently, on 6 October, the Government of Syria sponsored a public demonstration outside the besieged Turkish observation point in Ma’arrat An Nu’man. These protests often reflect a genuine popular rejection of foreign military intervention, but they also show the risk that local communities can be instrumentalized as part of a military tactic to deny access to rivals. Although rules of engagement with civilians have generally prevented the confrontations from turning violent, the tactic does transfer risk to civilian populations. All told, friction between U.S. and Russian troops on the ground in northeast Syria has grown, in large part because Russia likely does see a strategy imperative in expanding its presence around northeast Syria’s oil-rich communities and along the vital Iraq transit route through Al-Malikeyyeh. Although these frictions are unlikely to lead to a significant open confrontation between foreign troops, small-scale skirmishes are virtually guaranteed as they vie for the upper-hand in the same narrow battle space. There is, therefore, a risk of civilian infighting and increased tensions among civilians tapped by rival actors.

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below.

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

Council Journal … restrictive measures in view of the situation in Syria

What Does It Say? The EU has implemented restrictive measures against numerous high-ranking Government of Syria officials across seven ministries.

Reading Between The Lines: The move, like U.S. sanctions, obliterates the line between regime and state, and it marks a deepening commitment to an approach designed to pressure the Syrian government from the top down.

Source: Official Journal of the European Union

Language: English (multiple languages available)

Date: 16 October 2020

Why does the regime fear buried weapons in Dar’a?

What Does It Say? Damascus negotiators have persisted in demanding that Dar’a hand over weapons that have remained in the region since reconciliation, more than two years ago.

Reading Between The Lines: Damascus views forcibly disarming the south as a key pillar of its pacification strategy, as seen in the recent assault on Kanaker. Using checkpoint detention as a source of leverage to force families to hand over weapons — even if they have to buy them on the open market to do so — hints at the potential for overreach on the part of the security apparatus. Conditions remain volatile, and a violent reaction is possible.

Source: Nabaa Media Foundation

Language: Arabic

Date: 11 October 2020

How the Syrian Regime Undermines the Response to COVID-19

What Does It Say? The Syrian security apparatus has shifted from an early approach that treated COVID infections as security threats to one in which the state actively ignores the pandemic as it rides roughshod toward herd immunity.

Reading Between The Lines: Alternative service provision networks are key to meeting Syrians’ needs. This was true in far better times, but the state’s withering response to COVID-19 and its growing financial desperation have made grassroots efforts even more vital.

Source: Center for Global Policy

Language: English

Date: 13 October 2020

What Does It Say? Using spatial data analysis, the author creates a risk map for COVID-19 in northwest Syria.

Reading Between The Lines: Not surprisingly, the highest risk areas are located in northeastern Idleb governorate, and are the predominant host communities for IDPs fleeing bombardment on Idleb’s frontlines.

Source: MethodsX

Language: English

Date: 3 October 2020

Over WhatsApp, a free educational institute for rural Idleb

What Does It Say? An initiative to offer education programming over WhatsApp in northwest Syria has kicked off with approximately 1,000 students.

Reading Between The Lines: The program brings education access to students displaced by the conflict, but COVID-19’s deep impact on education globally highlights the value of alternative learning tools.

Source: Eqtsad

Language: Arabic

Date: 14 October 2020

What Does It Say? The article details the opening — one of many in a repeated cycle of openings and closings — for commercial and civilian transit between crossing points near the intersection of zones of control between the Government of Syria, SDF, and the opposition.

Reading Between The Lines: The crossings have been opened and closed repeatedly, yet crossline smuggling has persisted.

Source: Eqtsad

Language: Arabic

Date: 14 October 2020

Strategies and (survival) tactics: The case of Syrian oppositional media in Turkey

What Does It Say? The academic journal article explores the way Syrian opposition media navigated the novel legal and marketplace challenges of exile in Turkey.

Reading Between The Lines: Turkey’s hosting of opposition political forces has also invited parallel sectors, including humanitarian and media counterparts. How and whether these diasporas can embed themselves in host communities is a key consideration, and it may shape the nature of future donor-led programming through Syria’s regional neighbors.

Source: Journal of Alternative & Community Media

Language: English

Date: April 2020

The Wartime and Post-Conflict Syria project (WPCS) is funded by the European Union and implemented through a partnership between the European University Institute (Middle East Directions Programme) and the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR). WPCS will provide operational and strategic analysis to policymakers and programmers concerning prospects, challenges, trends, and policy options with respect to a conflict and post-conflict Syria. WPCS also aims to stimulate new approaches and policy responses to the Syrian conflict through a regular dialogue between researchers, policymakers and donors, and implementers, as well as to build a new network of Syrian researchers that will contribute to research informing international policy and practice related to their country.