Syria Update

26 October 2020

No hasty retreat: Turkey moves stranded northwest outposts

In Depth Analysis

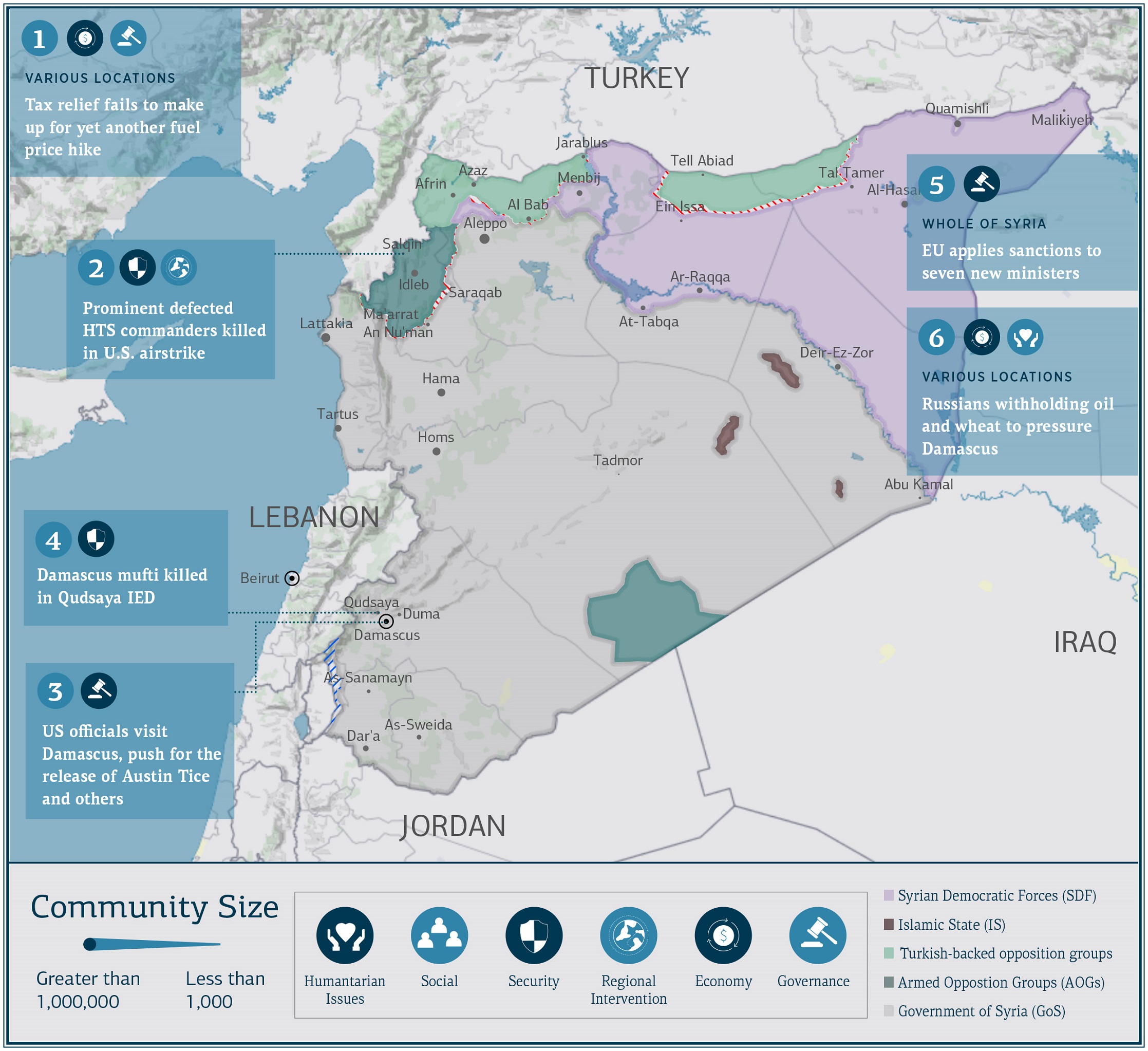

On 19 October, Turkey reportedly relocated the largest of its besieged military observation points from Murak in north rural Hama toward Qoqfin, in opposition-controlled southern rural Idleb. The remaining observation points located in territory recaptured by Government of Syria forces will reportedly be dismantled soon, including installations at Sher Mughar, Sarman, Tal Tufan, Iss, and Saraqab in Idleb governorate and Al Rahsidin and Sheikh Aqil in Aleppo. At the time of writing, there has been no official comment from Turkish officials on the military activities surrounding the points. However, the operations coincide with the deployment of additional Turkish troops to Joseph in Jabal Al-Zawyeh on 18 October, in apparent support for the relocation operations. More notable yet, the Idleb movements coincided with an escalation involving Turkish-backed forces on multiple other fronts. Between 19 and 22 October, media sources reported that the Syrian National Army (SNA) shelled multiple positions of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) around Ein Issa in northern Ar-Raqqa governorate, killing two SDF combatants and injuring several civilians. Skirmishes and shelling were also reported around Sayda, north of Ein Issa and near Menbij city, without any changes to positions.

The parallel streams of events come amid increasingly urgent chatter that Turkey is preparing for another incursion east of the Euphrates River. Turkey’s withdrawal at Murak is a bright-line indicator that a shakeup is possible — perhaps soon. Shelling and skirmishes at restive lines of contact have flared in recent weeks. That does not bode well. But it remains too early to tell exactly what Turkey will take in exchange for giving up its outposts in the northwest, where it has seemingly conceded that the Sochi frontlines are now a thing of the past, as are the hopes of return for many Syrians who were displaced to the opposition-held north.

A new tactic or a new deal?

The establishment of the observation points was one of the main outcomes of the agreement between Turkey, Russia, and Iran in October 2017 to establish a demilitarized zone in northwest Syria, with the partial aim of opening the M4 and M5 highways. However, the southernmost of Turkey’s observation points have been stranded as a result of progressive territorial gains by Government of Syria forces since August 2019 (see: Syria Update 22-28 August 2019). The waylaid observation posts have been soft spots for Turkey, and the outposts at Murak and Sarman, in particular, have been targeted for civilian demonstrations — among the few public protests the Government of Syria is willing to countenance.

Turkey’s withdrawal from the exposed positions has been interpreted as a measured concession to Russia, but Ankara has been keen to send a clear signal that its territorial ambitions across northern Syria remain unchanged, as it buttressed positions on frontlines located south of the M4 and deployed further Turkish troops in Jabal Al-Zawyeh. What prompted the withdrawal is a question that invites deeper consideration. Turkey’s refusal to withdraw its troops from territory otherwise held by the Government of Syria left it with a pressure point against Damascus that undermined the Syrian government’s authority and irked Moscow. Yet no development on the ground in Syria offers an adequate explanation for the maneuver’s timing, which comes more than a year after the stranded observation posts first developed into a sticking point. Since then, the posts have taken on second-class status, behind a bevy of more pressing issues clogging the channels between Ankara and Moscow, including a broadening portfolio of regional conflicts in which both states play outsize roles.

Give an inch, take a mile

Naturally, some in the Syria response have looked for signs that Turkey’s concession to Russia in the northwest will now prompt Moscow to yield to Turkish interests in SDF-held areas. There is precedent for such quid pro quo in earlier stages of the conflict (see: ‘Land Swaps’: Russian-Turkish Territorial Exchanges in Northern Syria). Yet the widening scope of Turkish-Russian foreign interventions has muddied the picture. Their bilateral coordination now spans a growing set of battle spaces, and a coordinated Russian concession may conceivably allow Turkish actions in Libya, the Nagorno-Karabakh region, or any number of long-coveted targets inside Syria, namely Menbij, Ain Al-Arab (Kobani), and Darbasiyah. Scale is also important. By itself, the Turkish drawdown in northwest Syria is likely too small a concession to prompt Russia to pull back its own forces in the northeast (or elsewhere). Moreover, although Russian troops have stood down and permitted SDF-National Army clashes as a pressure tactic against the SDF, Moscow has made a concerted effort to cleave the Self-Administration from its U.S. backers. In that respect, Russia has been all too happy using the menace of a Turkish incursion to pressure the Self-Administration. Yet it has done so to win concessions that redound to its own benefit and that of Damascus — not Ankara (see: Syria Update 7 September). The Kremlin has plied its diplomatic and military tradecraft hard to build a pragmatic relationship with northeast Syria’s Kurdish polity. It is difficult to imagine Moscow will sacrifice these efforts in exchange for so small a prize as an observation post in rural Hama. In this respect, intensifying skirmishes, shelling, and infiltration attempts near Ein Issa and Menbij are reminders of Turkey’s ambitions, which exist irrespective of Russia’s willingness to wield both stick and carrot for Turkey’s benefit.

End of the road for Sochi

The observation post maneuver prompts more questions than it answers. However, it leaves no doubt that the Sochi era is over. Heretofore, Turkish President Recep Tayep Erdogan has been emphatic that northwest Syria must return to Sochi lines, the ostensible basis for its observation points and the basic framework for its own presence in Idleb. Post-Sochi frontlines west of the M5 have already stabilized in western Aleppo, although areas south of the M4 remain in flux due to interruptions of joint Russian-Turkish patrols, infiltration attempts, and shelling by the Government of Syria targeting Jabal Al-Zawyeh.

No return: Reconciling to a new reality

Sochi is not the only era that has ended unceremoniously. On 22 October, the Syrian Parliament confirmed the Presidential Decree No. 22, nullifying the Reconciliation Commission that was formed in 2018 to replace the Ministry of National Reconciliation Affairs. The decision ends the mass reconciliation era and adds yet another layer of complexity to the issue of return, which is arguably more pressing in northwest Syria than anywhere in the country. More than 970,000 people were displaced in the intense Syrian government and Russia military campaign between December 2019 and March 2020, according to OCHA. Most fled deeper into northwest Syria, particularly Dana, Salqin, Afrin, and Azaz, where significant numbers still take refuge in makeshift camps and suffer from severe shelter, health, food, and livelihoods needs. Some IDPs have returned to areas captured by the Government of Syria, but many more remain displaced in an increasingly densely populated pocket of Idleb and western rural Aleppo that is the last preserve of the civilian and armed opposition. To those who remained displaced, Turkey’s commitment to Sochi held open the door for future return to an area free of influence by Damascus, under joint Russian-Turkish auspices. Presently, Russia and the Government of Syria maintain that return is possible only through local reconciliation committees, which are widely rejected by IDPs who doubt that either actor can safeguard their return. The parallel abnegation of Sochi and the reconciliation era is a double-whammy, throwing light on an unwelcome reality: for many Syrians who have been forced into the northwest, their displacement will continue, perhaps interminably.

Whole of Syria Review

1. Tax relief fails to make up for yet another fuel price hike

Various locations: On 21 October, Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad issued two legislative decrees to restructure Syria’s income tax in a nominal bid to relieve pressure on low-income earners. The first measure raises the ceiling for tax exemptions, permitting those who earn as much as 50,000 SYP per month to skirt taxes — up from 15,000 SYP. It also cuts the effective tax rate in the lowest bracket from 5 percent to 4 percent. The second measure provides a one-time stimulus payment of 50,000 SYP to all government workers and 40,000 to retirees. However, the tax relief is nullified — if not outpaced — by price rises for oil-based products, including heavy fuel oil and unsubsidized high-octane fuel. On 19 October, the Ministry of Domestic Trade and Consumer Protection more than doubled the price of commercially sold fuel oil, from 296 SYP per liter to 650 SYP. Meanwhile, the ministry increased the price of unsubsidized 95-octane fuel for the second time in October, raising it to 1,050 SYP per liter, up from 850 SYP (see: Syria Update 12 October). Worryingly, Minister of Domestic Trade and Consumer Protection Talal Barazi has also hinted that fuel subsidies could be eliminated altogether.

Death and taxes

The tax relief measures are driven more by public relations imperatives than the desire for effective fiscal stimulus. It is not immediately clear how many of Syria’s battered civil servants stand to benefit in the near term from the relief granted by a raised ceiling on taxable income. What is clear is that all Syrians will pick up the tab for rising fuel prices. As we should have noted earlier this month when Damascus raised the price of 95-octane fuel, the direct costs of the hikes have been borne by the few, yet the resulting upsurge in secondary costs will pass on to ordinary consumers through increased public transit fares and rising tariffs on commercial transportation for all manner of goods. To wit, on 19 October, Homs governorate raised its public and private transportation fares. Meanwhile, consumer price inflation continues unabated, and there is not a single public-sector salary in Syria that is on par with the cost of living in Damascus. The complete elimination of fuel subsidies should send klaxons blaring throughout the aid sector. Not only would it affect living expenses across all of Syria, but it would also presage the reduction of subsidies in other vital sectors. Aid actors must plan livelihoods, non-food items, and cash for work activities accordingly, and winterization needs will grow if heating fuels become more difficult to source.

For the Government of Syria, reducing taxes while raising direct consumption costs helps the state more accurately calibrate its social support costs, now the biggest portion of state discretionary spending. It is also likely to reduce overall subsidy spending and the volume of foreign reserves spent on imports. Yet what is good for the goose is not always good for the gander. The state’s retreat will force consumers to repurpose their tax relief to cover costs transferred to them by Damascus. Many will likely reduce consumption and rely more heavily on alternatives, including aid. Consumers have been critical of the changes, but they have few means of making their voices heard.

2. Prominent defected HTS commanders killed in U.S. airstrike

Salqin, Idleb governorate: On 22 October, the U.S. Army announced that it conducted a drone strike against “Al-Qaeda senior leaders meeting near Idleb.” The strike targeted a tent in Jakara near Salqin, where Samer Souad, a former Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS) commander, was hosting a dinner meeting. Seventeen people were killed in the strike, including Souad himself and his brothers Ibrahem and Amer. Other casualties included Hamoud Sahhar (the former HTS commander in Aleppo) and Abu Talha Al-Hadidi (the former HTS commander in the “Desert District”), both of whom defected from HTS and established the Fateh Battalions in 2019. Abu Hafs Al-Urdoni, the former general security commander of Jabhat Al-Nusra, who defected from the group after the latter cut its ties with Al-Qaeda in August 2016, was also among the fatalities. The U.S. statement noted that the strike would further curtail Al-Qaeda’s ability to carry out global attacks. The strike is the second deadly U.S. drone attack in October. On 15 October, two Huras Al-Deen commanders, Abu Zar Al-Masri and Abu Yousef Al-Maghribi, were killed in another drone strike in western Idleb (see: Syria Update 19 October).

Undermining Al-Qaeda but consolidating HTS

Every U.S. strike targeting Al-Qaeda figures in Idleb is followed by speculation that HTS coordinates with the International Coalition or Turkey to prove its pragmatic bona fides and take out its rivals. Direct coordination of this kind is difficult to fathom, but back channels may exist, and HTS has ample reason to permit the international community to do its dirty work. No doubt, HTS is under pressure to cut its ties with global Jihadist networks and prove the earnestness of its transformation into a moderate Islamic group of a strictly national character (see: Syria Update 5 October). Moreover, allowing outside powers to eliminate its rivals or defectors would spare the group the need to confront its former ideological partners or to abandon its ideology. Avoiding such internecine conflict is important to HTS itself. Open confrontation with hard-line groups such as Hurras Al-Deen would undermine the group’s efforts to halt its own fragmentation and ongoing defections.

In parallel, HTS continues to undermine its competitors on the other end of the spectrum. On 23 October, HTS raided several headquarters of Ahrar Al-Sham Movement in Ariha and Foah. HTS troops were accompanied by dismissed Ahrar Al-Sham military commanders Abu Al-Munzer, Abu Suhaib, and Abu Adham Kanakir, who sought to re-establish their authority within Ahrar Al-Sham with the help of HTS. In addition to weakening Ahrar Al-Sham, HTS has sought to steer the group toward leadership that is friendly to it, which may be an imperative for ensuring HTS domination over the military council that is expected to be established in Idleb (see: Syria Update 19 October).

3. US officials visit Damascus, push for the release of Austin Tice and others

Damascus: A delegation of senior U.S. officials made a surprise August visit to Damascus to negotiate for the release of American hostages, including journalist Austin Tice, believed to be held by the Syrian government, according to U.S. and Syrian media reports. The delegation included two high-ranking officials: deputy assistant to the president and senior director for counterterrorism on the National Security Council, Kash Patel, and chief U.S. hostage negotiator Roger Carstens. Media close to the Syrian government emphasized that the delegation’s discussions with National Security Office head Ali Mamluk concerned “a wide range of issues,” including the “so-called ‘kidnapped’ Americans.” The visit — reportedly the fourth by U.S. officials — produced no immediate outcome. In 2018, U.S. officials similarly met with Mamlouk in Damascus, again bringing up the issue of Tice’s captivity. In addition to Tice, five other U.S. nationals are believed to be held in Syria, including Majd Kamalmaz, a psychotherapist who had established a mental health clinic for Syrian refugees in Lebanon, and disappeared in 2017 at a government checkpoint the day after he arrived in the country.

All is fair in love and war…

Clearly, efforts are underway to free the hostages, yet little more can be said with certainty. Lebanon’s intelligence chief, Abbas Ibrahim, reportedly followed up the Damascus delegation and mediated during a multi-day junket in Washington earlier this month. Nonetheless, significant structural impediments remain. Abbas’s mediation is surely linked to Lebanon’s political fate, including the status of Hezbollah. Moreover, the hostage file would be delicate in the most cerebral of times. Now, the issue will be nigh impossible to disentangle from the parties’ divergent priorities, including Damascus’ demand for sanctions relief and a U.S. withdrawal from Syria, and the bureaucratic infighting and electoral imperatives that exist on the U.S. side.

Damascus has never publicly confirmed that it holds Tice and the other hostages, although the continuation of negotiations and information provided by local sources scuttle most doubts. It is not clear if attempts to barter down the terms for the hostage release — from troop withdrawals to personal matters at stake for regime insiders — have progressed. It is not encouraging or particularly surprising that the Syrian government has arrested officials who have asked about Tice’s whereabouts, according to recent local reports. On the U.S. side, the competing narratives emerging from various sectors of the national security complex evince the institutional pushback that has defined President Donald Trump’s bull in a china shop approach to foreign policy, of which Syria has been a clear flashpoint. U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo insists that Trump refuses to “buy” the hostages. The message is clear enough, but it is not evident that all quarters of government are united behind the idea. Trump’s first withdrawal orders in northeast Syria were thwarted in late 2018, and his northeast Syria border area drawdown in October 2019 followed some of the most bizarre direct diplomacy of the modern era. Both initiatives faltered amid military pushback and bipartisan political consensus in favor of continued U.S. military engagement in Syria. Nonetheless, Trump holds fast to his reputation as a kibitzer and a dealmaker. It is doubtful that a U.S. military withdrawal — even from Al-Tanf — is in the works, at least not in exchange for Tice. Nonetheless, Trump is an embattled incumbent in need of an electoral boost before the 3 November election. Winning the release of a long-detained American hostage would be a boost, so too would vacating the U.S. military presence in Syria and ending an unpopular war that most Americans would rather ignore — if they can overcome internal bickering to make it happen.

4. Damascus mufti killed in Qudsaya IED

Qudsaya: On 22 October, the Mufti of Damascus city and Rural Damascus, Adnan Al-Afyouni, was killed in a car bomb outside the Al-Sahaba Mosque in Qudsaya, according to media sources. Reportedly, Al-Afyouni was among those targeted via a makeshift bomb attached to the underside of his car. The detonation also injured the head of the Qudsaya reconciliation committee, Adel Mesto. At the time of writing, local sources report that Mesto is expected to survive.

There were also no claims made for the attack, a rare and deadly security incident in the Damascus suburbs. The mayor of Qudsaya, Nabiel Razmeh, was also targeted and killed in a similar fashion in an IED attack on 30 August 2019. However, it is not yet clear whether Al-Afyouni or Mesto was the primary target of the latest attack, if indeed either was singled out specifically. The mufti was close to the Syrian presidential palace and, like Mesto, was a prominent local figure deeply resented for his role in local reconciliation negotiations and resulting displacement near the capital. Al-Afyouni was especially noted for his sermons inveighing against the armed opposition, whom he branded “terrorists.” Similarly, Mesto was heavily in support of the government and advocated for the displacement of the armed opposition from Qudsaya and Al-Hameh.

Masters of reconciliation

The attack is a bold salvo against the Syrian regime, and it lashes out at two prominent individuals deeply implicated in the most reviled aspects of government restoration around the capital. One method for restoring government control in opposition areas forced “irreconcilable” elements of the population to flee to northwest Syria (a fate that was often met by more civil society actors than hard-boiled fighters). Likewise, Damascus also replaced local notables with regime loyalists. Both methods seeded resentment among those who stayed behind. The Qudsaya attack likely has more to do with the community’s antipathy toward Damascus than with the specific identity of the victims. In that respect, religious motivations are unlikely, although some have speculated that Iranian agents suborned the attack in a bid to undermine Syria’s Sunni majority. Equally conspiratorial, but somewhat less farfetched, is the suggestion that the attack stems from the parliament’s decision to end formal reconciliation. That decision ends an era, pricks old wounds, and leaves uncertain the future of many Syrians who remain outside the government’s purview. Yet there is no clear link between the attack and the parliamentary order.

Motivated by the desire to win international support, the Syrian government has gone to great lengths to demonstrate that the capital and surrounding areas are safe and life has returned to normal — with the possible exception of fuel shortages brought on by what it calls “the unfair blockade imposed by the U.S. Administration.” This attack undermines that narrative — but it does not overturn it altogether.

5. EU applies sanctions to seven new ministers

Whole of Syria: On 16 October, the European Union placed restrictive measures on seven recently appointed Syrian ministers: Talal Barazi (Minister of Domestic Trade and Consumer Protection), Loubana Mouchaweh (Culture Minister), Darem Taba’a (Minister of Education), Ahmad Sayyed (Minister of Justice), Tammam Ra’ad (Minister of Hydraulic/Water Resources), Kinan Yaghi (Minister of Finance), and Zuhair Khazim (Minister of Transport). Brussels stated that these ministers were sanctioned over repression of Syria’s civilian population at the hands of the Government of Syria. All the ministers except Barazi were appointed to their posts in August. Barazi was promoted in May, following a bloodletting calibrated to dampen public frustration over rapidly increasing prices and currency devaluation (see: Syria Update 18 May).

Cutting the gordian knot of Syria sanctions

The EU’s Syria sanctions are narrower than the sanctions leveled by the U.S., but they have been no less encompassing of government activity. Restrictive measures on ministry officials have been routinely renewed without significant debate in recent years. Although Europe’s sanctions policy is independent, Europe’s exemptions and narrower targeting are nullified by Washington’s unrelenting blunderbuss approach. This complicates efforts to leave specific carve-outs, including for aid activities. The fundamental coordination problem complicates future efforts to wind down sanctions in a progressive, stepped manner. Critics of sanctions and their supporters alike agree that the West’s approach to Syria has caused harm to civilians, not least because sanctions undermine the Syrian state, and no amount of aid will make up for the withering of central state capacities. How to deploy sanctions more effectively — to reduce unintended harms and use leverage to generate meaningful concessions — is a matter of continuing debate. What is clear is that the Syrian regime presides over an embattled state locked in a conflict it views as existential. It can and will continue to privilege its own survival above all else. Western policymakers contemplating new approaches to Syria must bear in mind that efforts to instrumentalize the suffering of the Syrian populace to create internal pressures within the Syrian state are unlikely to lead to meaningful change — but they will perpetuate the suffering.

6. Russians withholding oil and wheat to pressure Damascus

Various locations: On 18 October, the Syrian Minister for Economy and Trade Mohammad Samer Al-Khalil announced that the country requires between 180,000 and 200,000 tonnes of wheat per month in order to meet domestic demand. Al-Khalil attributed the wheat shortages in government-held areas to “militias” (i.e. the SDF) that preside over the most important areas of grain production. The declaration follows earlier reports that the state has introduced new rules limiting individual purchases at state-subsidized bakeries, and that households are reducing consumption of wheat-based products in government-held areas in particular (see: Syria Update 21 September). This new situation reflects a broader downward trend in food security in these areas, which continue to labor under the effects of international sanctions, soaring inflation, currency collapse, coronavirus restrictions, and the unfavorable political economies of cross-line and international food imports.

Flour power

The statement clarifies Syria’s wheat consumption needs — which have been subject to difficult-to-substantiate speculation — but it also focuses attention on the state’s continuing inability to secure foreign imports. In late September, Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad stated that he wanted to increase Russian investment to help alleviate some of the country’s most pressing economic challenges. A Syrian delegation was assembled to discuss financing and import options with Russian officials, yet the intervening period has instead signaled that Moscow is more interested in capitalizing on Syria’s weakness to extract further economic dividends, and perhaps to its cooperation with the UN-led Syrian constitutional process (see: Syria Update 12 October). Indeed, Russian aid and credit lines for wheat and other essential imports were not forthcoming in early October, whilst a Russian oil shipment to Syria has reportedly been held back owing to non-payment of fees. Notably, it is understood the vessel in question is partially financed by the head of the Syrian government’s constitutional committee delegation and state-linked businessman, Ahmed Al-Kuzbari.

The Syrian government is thought to have responded by blocking pre-existing natural resource exploitation agreements with Russia. However, an inability to meet current wheat shortfalls in the absence of Russian support suggests it will be unable to sustain this position indefinitely. Indeed, domestic wheat production may have recovered somewhat in the past two years, but output is still far short of pre-crisis averages and 2020 consumption estimates. Under current conflict-related economic conditions, Syria’s heavy reliance on an import partner, which appears increasingly set upon leveraging concessions in return for assistance, suggests Syria’s food security outlook will worsen until it reconciles with Russian demands. Given this may only represent a temporary escalation, the extent to which these events portend a less conciliatory tone in Syrian-Russian relations is uncertain. In the meantime, further measures will likely be implemented to moderate household demand for wheat products, and the current impasse between the two parties is almost certain to affect the pricing and availability of other key commodities.

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below.

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

What Does It Say? The rules of acceptable political behavior in Syria are continuously changing — making it more difficult to navigate the few dissent channels that did exist in the authoritarian state.

Reading Between the Lines: In the Syria of yesteryear, criticizing the government was permissible, attacking Al-Assad was beyond the pale. The reality is that Syrians now fear that acts of tolerable resistance today will land them in hot water tomorrow.

Source: Carnegie

Language: English

Date: 22 October 2020

The Syrian Conflict: Proxy War, Pyrrhic Victory, and Power-Sharing Agreements

What Does It Say? The Syria conflict offers new insights into the prospects of power-sharing in a post-conflict Syria where, despite a decisive military victory, there is no guarantee that to the victor go the spoils.

Reading Between the Lines: The complexity of the Syria conflict prompts a rethink on the orthodox understanding of a post-conflict power-sharing model. In short, the Syrian state is desperate, and its likely military victory will not necessarily give it a free hand.

Source: Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism

Language: English

Date: 2020

Thirty documents to help you prove and protect your ownership in Syria

What Does It Say? The article and accompanying video discuss the multitude of documents that Syrians can use to assert their HLP rights.

Reading Between the Lines: In many cases, HLP barriers are deliberate, meaning that alternate property validation mechanisms will be critical in ongoing aid activities and in future reconstruction scenarios.

Source: Rozana

Language: Arabic

Date: 10 October 2020

Qaterji Company puts its hand on the cotton crop in Deir Ezzor

What Does It Say? The Qaterji company has sought to corner the cotton crop in Deir-ez-Zor, offering 600 SYP, down from 700 SYP as established by the Syrian government.

Reading Between the Lines: Cotton is a strategic resource in Deir-ez-Zor, and it has frequently provided the basis for war economy activities. Famously, the Saroj family sought to corner the cotton market to feed the crop into its own overland shipping operation for processing in Damascus. The family’s use of local connections to prevent the rehabilitation of the Deir-ez-Zor cotton processing facility is evidence of inherent conflict that can arise between local war economy actors and communities as a whole.

Source: I am a Human Story

Language: Arabic

Date: 19 October 2020

What does a Syrian smoke? Colored Iranian and Emirati poisons

What Does It Say? Syria’s nationally produced cigarettes are being displaced because they cannot be produced affordably or in adequate quantities to meet the demand of the Syrian market.

Reading Between the Lines: Syria has become an experimental ground for tobacco from the Gulf, with Syrians trying vying for cheap alternatives to the 1,800 SYP nationally produced cigarettes. Quality issues are significant, and health concerns abound. The displacement of local produce is also a sign that one of Syria’s oldest and proudest traditions — tobacco production in its fertile western regions — is potentially unsustainable.

Source: Eqtsad

Language: Arabic

Date: 19 October 2020

What Does It Say? The Syrian Democratic Council has released the families of Syrian ISIS members from the Al-Hol camp, and it has mooted the possibility of amnesty for other such families to demonstrate it can solve the social-cohesion challenges that continue to bedevil northeast Syria.

Reading Between the Lines: Attempts to address the issue of detained Syrian families in Al-Hol are one thing. Expansive action on the thousands of camp residents who are implicated is something else. Moreover, such actions do not address the cases of families of non-Syrian ISIS members, whose future remains up in the air.

Source: Hal Net

Language: Arabic

Date: 20 October 2020

An Israeli raid on Quneitra, southern Syria

What Does It Say? An Israeli raid on southern Syria resulted in a missile hitting a school in Quneitra, although the damage was limited to material structures.

Reading Between the Lines: Attacks on civilian infrastructure are rare, and a source of potential animosity that may complicate Israel’s attempts to peel away ordinary Syrians from the Iranian axis.

Source: Skynews Arabia

Language: Arabic

Date: 21 October 2020

Counter-Terrorism Force nabs terrorist cell in Tripoli and Khoms

What Does It Say? Four people — reportedly Syrians — were arrested for suspected links with terrorist entities in Libya.

Reading Between the Lines: The incident highlights Syria’s role as a nexus of regional instability, from which long-running issues will be exported to other contexts to create knock-on effects that will compound over time.

Source: The Libya Observer

Language: English

Date: 18 October 2020

Cementing dispossession: the bitter reality of reconstruction in Syria

What Does It Say? Displacement through urban redevelopment is the flip-side of Syria’s reconstruction, and it is a key tactic used by the Syrian regime to punish former opposition communities.

Reading Between the Lines: Continued violations of HLP rights will reward loyalist cronies and punish communities that rose up against the regime. These challenges will persist well after the conflict subsides.

Source: Syria Direct

Language: English

Date: 19 October 2020

The Wartime and Post-Conflict Syria project (WPCS) is funded by the European Union and implemented through a partnership between the European University Institute (Middle East Directions Programme) and the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR). WPCS will provide operational and strategic analysis to policymakers and programmers concerning prospects, challenges, trends, and policy options with respect to a conflict and post-conflict Syria. WPCS also aims to stimulate new approaches and policy responses to the Syrian conflict through a regular dialogue between researchers, policymakers and donors, and implementers, as well as to build a new network of Syrian researchers that will contribute to research informing international policy and practice related to their country.