Syria Update

2 November 2020

Russia pushes dead-end returns conference

In Depth Analysis

On 29 October, a Russian delegation headed by special envoy Alexander Lavrentiev visited Damascus to further Moscow’s plans for a two-day international conference on refugee returns, to be held in Damascus on 11-12 November. The visit follows reports that Moscow had been forced to call off the planned conference due to hold-outs among key regional and international players, namely Turkey, the UN, and concerned Western states. Reports of the event’s cancellation are premature, and the conference likely will take place. Although it is highly improbable that the event will kick-start substantive progress on refugee returns, such an outcome is not the point. The event is a cosmetic maneuver to showcase the Government of Syria’s willingness to play ball on refugee returns and, more importantly, to demonstrate Russia’s unique capacity to take the umpire’s chair for regional dialogue on Syria.

At first blush, the event would be the most significant high-level diplomatic effort on returns in recent memory. The willingness of some regional players to come to the table under Russian auspices signifies the continuing salience of refugee returns in domestic politics throughout the region. Russian delegations have already conducted discussions with heads of state in Lebanon and Jordan, two of the three most significant host nations. As of writing, participation by Turkey, the nation hosting the most Syrian refugees, is uncertain, given the plans to conduct the conference in Damascus, a seemingly inviolable red line for Ankara. Likewise, the international community has shunned the planned conference. U.S. deputy ambassador to the UN Richard Mills dismissed the event as shadow play and noted that it is taking place outside UN auspices and without the support of major international powers. It is particularly notable that Moscow is pushing the conference at the same time the UN-led constitutional process is stalling over intransigence on the part of the most cohesive bloc, that fielded by Damascus.

None of this has blunted Damascus’s apparent enthusiasm for the returns initiative. The Syrian Presidency claimed that the conference would further efforts to “alleviate the suffering of the Syrian refugees abroad and open the way for them to return to Syria and live a normal life.” Russia’s UN Ambassador Vassily Nebenzia lamented that the international community had come together “to discredit this humanitarian initiative.” Nebenzia was less bullish than the Syrian Presidential Palace but nonetheless emphasized that “the forum will provide a platform for substantive dialogue with all stakeholders on all issues related to providing assistance to Syrians returning to their homes.”

Getting real on returns

The Government of Syria’s commitment to refugee returns is superficial at best. In pragmatic terms, the need to provide costly social support such as subsidies and services for Syrians who already reside inside the country far outstrips the state’s meager capacity. Hemmed in by sanctions and shouldering the costs of a war it views as existential, the Syrian government faces a continually diminishing capacity to carry out basic functions. Facilitating the return of additional refugees will aggravate this further. There is also a considerable political and demographic impediment to the effort. Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad has been unambiguous that the conflict will lead to “a healthier and more homogeneous society in the real sense.” Syrians who fled the country are viewed with suspicion, particularly if they had ties to armed or civil opposition movements, or have been denounced by former neighbors, distant relatives, or paid informants, as many have. Syrians residing abroad face a litany of functional barriers to return, nearly all of which are the direct result of deliberate Syrian government policy or the practices of arcane security and intelligence authorities.

The fact that returns are unlikely does not mean that Russia’s efforts will be for naught. Syria continues to furnish Russia with a space to demonstrate its power as an international mediator. The Sochi agreement is testament to Moscow’s proven ability to get all major actors reading from the same script in Syria, albeit to limited effect. There has been debate over how the international community can capitalize on Russia’s access to improve the conditions for Syrians who do voluntarily return. Certainly, Russia does wield influence in Syria, but its power to meaningfully shape “soft issues” like returns will remain constrained by its own lack of interest in doing so. More relevant is the reality that large-scale voluntary returns will not occur in the foreseeable future. Despite the worsening economic conditions and social and political upheaval roiling the four neighboring states that are the largest hosts of Syrian refugees — Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon, and Iraq — many displaced Syrians are, for now, neither willing nor able to return.

Whole of Syria Review

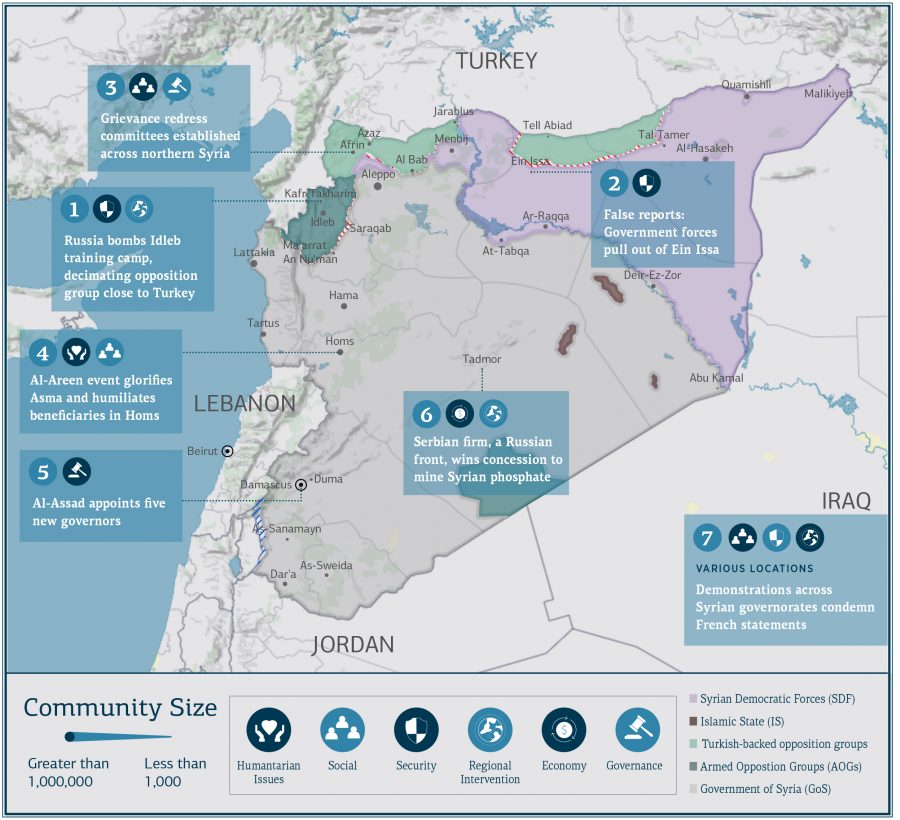

1. Russia bombs Idleb training camp, decimating opposition group close to Turkey

Kafr Takharim, Idleb governorate: On 26 October, media sources reported that Russian forces bombed a training camp used by Faylaq Al-Sham (FAS) — an armed group that is among those most closely affiliated with Turkey — near Kafr Takharim in the western Idleb countryside, killing dozens. Russian media report that most of the casualties were FAS fighters, although some civilians also died. Local sources indicated that approximately 100 people were killed altogether. Meanwhile, media sources also indicated that Government of Syria forces and Iran-backed armed groups are gathering on the Idleb frontlines in preparation for an offensive. The reports said opposition forces across the frontlines have been on the lookout for breakdowns in the 5 March ceasefire agreement (see: Syria Update 5 March), and that they are ready to respond with force if needed. Local sources also stated that artillery and shelling have increased in Ariha.

Cry ‘Havoc,’ and let slip the dogs of war?

Almost universally, the provocative strike has been interpreted as a shot across the bow by Moscow. Exactly what message it is meant to deliver and which theater of the regional Turkish-Russian contest it is meant to influence is anyone’s guess. Many analyses have pointed to the persistent violation of ceasefire terms in Nagorno-Karabakh as the source of Russia’s pique. Perhaps so, but it is also worth noting that Russia has a long history of deliberate attacks on Turkish-backed armed groups in Syria, and the two have plenty to fight over in Syria, too. Turkey’s drawdown from its Murak observation point has been seen as one part of a quid pro quo, although where the other shoe will drop (if at all) remains unclear (see: Syria Update 26 October). On 28 October Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan described the strike as evidence that “a lasting peace and calm is not wanted in the region.” Erdogan also intimated that Russia has failed to live up to its promises to rein in Kurdish forces in northern Syria. The latter claim is dubious, given Russia’s limited influence in the area and the reality that outside Al Bab, formal Kurdish forces and affiliated groups are suspected in almost no serious line-stepping. However, the claim follows reports that a Kurdish suicide bomber infiltrated Turkey for an attack in Hatay province after crossing over from Syria. Seldom in the Syria conflict has Erdogan had difficulty conjuring casus belli, but the Russian airstrike, the crossborder attack, and reports of building pressure on Idleb frontlines make it even harder to stand down now. If violence does flare on Idleb frontlines, coordinated attacks can be expected in northeast Syria, sooner or later. Moscow and Ankara are keen to level mutual recriminations, but in the end, they have landed on a well-worn pattern of trading like for like in Syria and elsewhere.

2. False reports: Government forces pull out of Ein Issa

Ein Issa, Ar-Raqqa governorate: On 26 October, multiple media sources reported that Government of Syria and Russian forces pulled out of Ein Issa, a frontline community that marks the southernmost boundary of Turkish-backed military advances in northeast Syria. Syrian media reported that a column of 37 vehicles left Ein Issa for unknown reasons. Sources also reported that the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) had been digging trenches in the vicinity of the community in anticipation of a confrontation with the Turkish-backed National Army. The reports also suggested that the National Army has been urging Turkey to support the resumption of the Peace Spring military operation due to the perceived threat from the SDF. Despite the widespread nature of the reports of a drawdown, at the time of writing, multiple local sources indicated that Government of Syria and Russian forces have not pulled out of Ein Issa and that the news of their departure is a deliberate fabrication.

Syria in the disinformation age

The spread of false information concerning military movements in northeast Syria comes at a particularly sensitive time. Frontline communities have kept a weather eye open since Turkey’s withdrawal from its observation post in Murak, Hama governorate — a likely precursor to anticipated military operations in the northeast (see: Syria Update 26 October). Government of Syria forces returned to Ein Issa in October 2019, following the Turkish Operation Peace Spring, and alongside Russia, they form a breakwater against which Turkish advances have halted. False reports of their withdrawal are likely part of a wide-ranging, deliberate ploy to undermine public confidence in the SDF and increase the pressure for rapprochement with Moscow as well as Damascus. Ruses, deception, and disinformation are tactics as old as warfare; the spread of false reports concerning northeast Syria is a reminder for programmers and decision-makers alike that digital disinformation is not limited to electoral politics.

3. Grievance redress committees established across northern Syria

Afrin, Aleppo governorate: A series of public complaint offices has opened in Turkish-controlled northern Syria, local media reported on 23 October. Turkish officials and representatives for various armed factions backed by Turkey reportedly created the grievance redress system to reduce the social tensions that are now bubbling across all areas of Turkish military and administrative influence in Syria, including northern Idleb governorate, Euphrates Shield, Olive Branch, and Peace Spring areas. In Afrin, a poster child of communal discontent with the fruits of Turkish-guided administration, Syrian National Army (SNA) factions and local notables convened a meeting in late August, focusing on local aggrievement over widespread property confiscations and the extortion of olive producers. With Turkish backing, the local Restitution and Grievance Redress Committee formed, and from mid-October to 23 October, it heard approximately 300 complaints, of which 100 reportedly met with favorable rulings, including the return of residential property or agricultural land. In some cases, owners accepted offers to sell their assets. On 24 October, the committee reportedly prohibited the taxation of fruit trees in Afrin.

A fair hearing — for some

For Turkey, creating a system to hear complaints will reduce social tensions and provide basic good governance where arbitrary military rule has prevailed. Local communities have welcomed the committee’s formation. It gives Syrians what so many desperately want and need: access to a formalized — albeit imperfect — system of restitution that eliminates the need to confront the armed factions that Turkey has deputized to manage its northern Syria statelets. Yet the system’s guarantees are not bulletproof. Retribution is still possible, and there are limitations to contract freedom, independent criticism, and good-faith sales in communities densely populated by armed actors. More important yet, there are some grievances the system cannot redress: namely the property claims of many of the 137,000 Syrians who were displaced when Turkey militarily captured the predominantly Kurdish Afrin area in 2018. In effect, the new system co-opts those who have stayed behind (or moved into the community) into an administrative bureaucracy founded on an injustice that is now likely irreversible.

4. Al-Areen event glorifies Asma and humiliates beneficiaries in Homs

Homs, Homs governorate: Al-Areen Humanitarian Foundation has fired its Homs branch manager and board following a public backlash over a botched public rally-cum-aid distribution meant to commemorate the foundation and provide aid to an estimated 20,000 attendees, primarily war-wounded, at Baba Amr stadium on 25 October. The Syrian government drove up attendance by using both carrot and stick. Attendees were led to believe the distribution — taking place on the one-year anniversary of Al-Areen’s formal establishment — would be attended by Asma Al-Assad. The event entailed the implicit threat of force, being surveilled by intelligence and security forces, with beneficiaries made to understand that non-attendance jeopardized their access to aid. After waiting some five hours, without public health precautions such as social distancing, attendees were “humiliated” when the event ended without an appearance by a major official, and they were left empty-handed, apart from meager rations of water and snacks distributed by Al-Areen.

Salt in an open wound

The event’s failure displays either unconscionable tone-deafness on the part of its organizers or deliberate cruelty in the interest of proving a point: the Syrian population must kowtow to the national security state’s dictate. In either case, the event will be seen as a flop. The proceedings have widely been interpreted as a public rally designed to glorify Syria’s first lady, Asma Al-Assad, who has been at the helm of Al-Areen (formerly Al-Bustan) since it was prised from the hands of Rami Makhlouf. If the event was intended to show the unremitting presence of the security state, it did so, yet it will have been a pyrrhic victory. The ham-fisted execution created such universal outrage in person and on social media, that it forced Al-Areen to issue a swift public condemnation, citing “big mistakes” and a failure by local staff to communicate with headquarters. Syrians have few means of voicing discontent with the state, but the event is a reminder that the most egregious abuses can cross a line, as seen in recent online scandals over dehumanizing images of Syrians forced to queue in cages to buy bread and fuel, or reports of beatings by security forces and abuse at the hands of public servants.

That the event took place in Baba Amr, a neighborhood where the opposition was forcefully expelled in 2012, is also symbolic, but less so than the images that will likely shape its most enduring memories: the stories-high image of Asma Al-Assad that was hung during the event. In that sense, the event has been interpreted as the embodiment of the first lady’s rise. It cements Asma Al-Assad’s wholesale displacement of Makhlouf, formerly Syria’s most prominent man on the make. Al-Assad has absorbed Makhlouf’s Al-Bustan Association into her own charitable empire. Other battlefields remain. On 25 October, Rami Makhlouf repeated his demand that Damascus unlock 7 billion SYP from revenues of Syriatel profits controlled by his firm, RAMAK, to be distributed to coastal areas decimated by fire (see: Syria Update 19 October). Makhlouf’s demand came only hours after Syria Trust for Development, an organization established by Asma Al-Assad, announced it had collected 6 billion SYP for the same purpose.

5. Al-Assad appoints five new governors

Damascus: On 26 October, Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad issued a series of presidential decrees to appoint new governors in five different governorates. The appointees are as follows:

- Ar-Raqqa: Abdul Razzaq Khalifa

- Deir-ez-Zor: Fadil Najjar

- Hama: Mohammad Tariq Kreashati

- Idleb: Mohammad Nattouf

- Quneitra: Abdul Halim Khalil

The measure comes only months after Al-Assad named five new governors — in As-Sweida, Al-Hasakeh, Dar’a, Homs, and Quneitra — in a fusillade of appointments earlier this year.

Reshuffling the deck

Of the 14 Baath Party apparatchiks who began the year as governors in Syria, only five still hold their offices, a key instrument of regime influence in provincial and local affairs. Not surprisingly, the governors who have avoided being reshuffled all preside over priority governorates: the capital (Damascus), the epicenter of reconstruction and locus of Syria’s urban development boom (Rural Damascus), the nation’s manufacturing hub (Aleppo), and the Alawite coastal heartland (Tartous and Lattakia). The appointments have clear importance for aid work and locally driven development activities. Syrian governors function as a vital gear in the interlocking system that gives Damascus continuing influence despite the lofty promises of administrative decentralization under Law 107. As such, they are integral to a system that has the power to interrupt (or shepherd) aid activities, development projects, and business activities undertaken by community figures themselves (see: Arrested Development: Rethinking local development in Syria). Donor-funded aid activities also rely upon permissions and security approvals from provincial governors. While a single top-down authority is often not a sufficient guarantee of unfettered access, it does much to set the tone for an operating environment. As expected, all the new appointees are party men. None have been given their offices to use them independently, yet some latitude likely does exist, particularly for locally popular activities that do not conflict with the direct financial or personal interests of local notables. Aid actors’ entry strategies must accord with this reality.

6. Serbian firm, a Russian front, wins concession to mine Syrian phosphate

Tadmor, Homs governorate: On 22 October, Syrian media reported the parliament ratified a contract granting Serbian mining company Womeco Associates the rights to exploit Syria’s largest phosphate mine, the Sharqiyyah mine near Tadmor. The agreement grants the company 70 percent of the profits, mirroring the terms of a similar contract signed with Russian firm Stroytransgaz. To that end, Syria Report has identified the Serbian firm as a likely Russian front, controlled via a shell company in Oman. The contract reportedly guarantees the Syrian state 1 billion SYP ($398,000 in real terms, roughly double that amount at the preferential rate used for most government transactions) in land rent, fees, taxes, and other concessions. It is not immediately clear when the mine will become operational.

Trickle-down economics in a time of sanctions

Russia has been the most adept of international actors when exploiting Syria’s vulnerability for its own commercial advantage. Crucially, Iran has so far failed to convert its on-the-ground influence in Syria into financial gain, despite a similarly advantageous agreement to mine Syrian phosphates signed earlier this year. While there are myriad likely causes for this inability, one of the most noted divergences between the Russian and Iranian strategies is Iran’s apparent ambition to convert Syria into a long-term consumer market. Earlier this month, the Syrian-Iranian Joint Chamber of Commerce opened a trade center, designed as a launchpad for Iranian exports to Syria, in the Damascus free trade zone. The center is meant to boost exports to $1 billion annually, a sum that is approximately five times their current value. The Serbian phosphate deal is a signifier that a desperate Syrian state will be willing to accept pennies on the dollar for any deal that will help it exploit the resources that remain available in an increasingly hostile, highly sanctioned, international environment. These sanctions are unlikely to close off avenues of money-making altogether. Yet they do prime the pump for the Syrian government to turn to its foreign backers and well-connected business people to evade legal snares, forcing them into a shell game that all but guarantees that smaller shares of the profits extracted from the ground in Syria benefit the Syrian state, and even less trickles down to the people.

7. Demonstrations across Syrian governorates condemn French statements

Various locations: On 25 October, media sources reported that demonstrations took place in multiple Syrian governorates condemning the statements of the French president Emmanuel Macron regarding caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad. Demonstrations erupted in Idleb city, Binish, and Kelley in Idleb governorate; Ras Al-Ain in Al-Hasakeh governorate; Moezleh, Gharanij, and Elhisan in Deir-ez-Zor governorate; Jarablus and Azaz in Aleppo governorate; Dar’a Al-Balad; and Ar-Raqqa City and Tabaqa in Ar-Raqqa governorate. On 30 October, protests were renewed in Idleb, Ar-Raqqa, Deir-ez-Zor, Al-Hasakah, and Dar’a governorates. Calls to boycott French goods were also reported in Aleppo, Idleb, and Ar-Raqqa, which drove the administration of Bab Al-Hawa and Tal Abied crossings to ban the entry of French goods. The demonstrations triggered several security incidents. The SDF cracked down on protesters in Gharanij, east of Deir-ez-Zor, and in Tabaqa, west of Ar-Raqqa, leading to injuries among two people, and the SDF arrested 13 people in Shiheil. Two people who reportedly held aloft ISIS flags in a demonstration in Ras Al-Ain were arrested by SNA forces, which condemned the display in an official statement. Of note, investigations have revealed that the suspected killer of the French teacher had been in contact with a Russian-speaking fighter in Idleb.

The French connection (to Idleb)

Over the course of the past two weeks — and for the first time since 2011 — demonstrations erupted across all of territorial Syria over a single shared concern. Previously, widespread protests have been fuelled by factors such as economic marginalization, failure to reconcile, and instability. This time, the issue of identity (Islamic identity in this case) has also proven capable of marshalling a synchronized, though uncoordinated, response. Calls for a boycott are unlikely to have a major impact, considering the limited volume of French products entering local markets in Syria, especially in the northeast and northwest of the country. However, if strongly voiced criticisms escalate and public demonstrations grow, they may impair the ability of French NGOs and aid workers to operate.

More importantly, linking the French attacker — however tenuously — to a suspected foreign fighter based in Idleb governorate may impart momentum on the International Coalition’s activities in Syria. However, a growing rift between France and Turkey also clears the way for a convergence between the interests of Russia and France in Syria, which may increase the pressure to support Russian military actions in Idleb or intelligence coordination over the issue of terrorist groups in the area.

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below.

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

What Does It Say? Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and the U.S. appear to be coordinating efforts to take out extremist actors in northwest Syria.

Reading Between the Lines: HTS-U.S. coordination is often-touted, particularly among HTS’s antagonists. Backchannels probably do exist, but formally, the U.S. considers HTS a wing of Al-Qaeda. What is clear is that by conducting attacks on other armed groups in Idleb, both actors are taking actions that are to their mutual benefit.

Source: Syria Direct

Language: Arabic

Date: 26 October 2020

What Does It Say? The article explores the changing nature of Russian policy toward Syria and the surrounding region, in light of the Russian delegation’s early September visit to Damascus.

Reading Between the Lines: Russian policy in Syria has been crafted to squeeze Damascus for economic concessions while hoisting aloft a comprehensive military and diplomatic aegis. Among the big bets outlined in the article is the view that a Biden administration will de-prioritize Middle East engagement and wind-down a presence in Syria. This is a mis-read. Personnel is policy, and this will likely be doubly true in a Biden administration composed of insiders. If this is borne out, Syria may be caught between competing long-term agendas that are broadly incompatible.

Source: Emirates Policy Center

Language: English

Date: 22 September 2020

What Does It Say? In September, 116 people were arbitrarily arrested in Afrin and disappeared by the various militant factions operating there.

Reading Between the Lines: Such incidents are likely to continue in the area, largely because of continuing instability and the history of impunity. Even in a post-conflict Syrian environment, Afrin is unlikely to see a return to normality due to the large scale of the displacement of Kurds.

Source: Syrians for Truth and Justice

Language: English

Date: 26 October 2020

As detainees are released from Al-Hol, concerns in Syria’s Euphrates river valley

What Does It Say? Syrian family members of ISIS fighters, detained in Al-Hol camp, were among the 600-odd detainees who were released from the camp.

Reading Between the Lines: The slow progress on releases from Al-Hol shows that public statements about the desire to empty to camp and the reality of doing so are two very different things. Detentions among bread winners, tribal relations, and family members in Al-Hol will continue to fuel discontent in post-ISIS communities, where patience has run thin and the SDF is being forced to shoulder greater responsibility for the governing challenges that it has taken on since stepping into the void left by the Islamic state.

Source: Middle East Center for Policy and Analysis

Language: English

Date: 25 October 2020

Syria fuel crisis eases as Iran delivers new oil supplies

What Does It Say? Following highly publicized shortages, Iran has delivered oil and gas to Syria, somewhat alleviating the shortage exacerbated by international sanctions.

Reading Between the Lines: The supplies are likely a welcome relief to the civilian population, although long-term considerations such as fuel supply remain a foremost concern.

Source: Reuters

Language: English

Date: 23 October 2020

Pedersen from Damascus: Ten years of conflict is a very long time

What Does It Say? The UN Special envoy to Syria met with Government of Syria officials in Damascus, pressing them ahead of an expected fourth round of constitutional talks.

Reading Between the Lines: Pedersen is facing growing pressure to concede that the UN-sponsored peace talks have failed, largely because of intransigence on the part of the Government of Syria delegation.

Source: Enab Baladi

Language: Arabic

Date: 25 October 2020

Syrian civil society organizations in Turkey

What Does It Say? The exhaustive report considers the importance of Syrian civil society groups in Turkey.

Reading Between the Lines: Civil society groups were heavily stifled by the Syrian government, which permitted only a narrow expression of views among organizations with approved agendas. This has denied safe space for discussion, but the repression has been far from total, and as we have argued, civil society requires a broad definition to capture the full spectrum of activities being carried out.

Source: Haroon

Language: Arabic

Date: 26 October 2020

Who is the new Iranian envoy to Syria, Hamid Saffar Harandi?

What Does It Say? Iran has appointed a new special envoy to Syria, Hamid Saffar Harandi.

Reading Between the Lines: No change of tack can be expected. Iran’s leader personally picks special envoys, essentially ensuring that they will fulfill his objectives.

Source: Syria Direct

Language: Arabic

Date: 22 October 2020

Syria has entered an economic abyss: Expectations of higher gas and bread prices

What Does It Say? Syria is in the midst of one of its worst economic crises, with bread and fuel prices continuing to spiral.

Reading Between the Lines: The timing could not be worse. As winter approaches and the specter of electricity shortages comes into view, the coming season appears bleak, indeed.

Source: Hal Net

Language: Arabic

Date: October 2020

What Does It Say? The Aleppo City Council has issued a decree stating it will compensate people for damaged property in areas with planned reconstruction and for building works it has deemed essential.

Reading Between the Lines: While admirable, this decree seemingly leaves out people whose property is not within the planned reconstruction zones, and as always, HLP claims by the displaced will be difficult to establish.

Source: The Syria Report

Language: Arabic

Date: 21 October 2020

The Wartime and Post-Conflict Syria project (WPCS) is funded by the European Union and implemented through a partnership between the European University Institute (Middle East Directions Programme) and the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR). WPCS will provide operational and strategic analysis to policymakers and programmers concerning prospects, challenges, trends, and policy options with respect to a conflict and post-conflict Syria. WPCS also aims to stimulate new approaches and policy responses to the Syrian conflict through a regular dialogue between researchers, policymakers and donors, and implementers, as well as to build a new network of Syrian researchers that will contribute to research informing international policy and practice related to their country.