Syria Update

16 November 2020

What Biden’s win means for the Syria response

In Depth Analysis

Having failed to convince American voters that he had lived up to his promise to make America great again, U.S. President Donald Trump was repudiated by voters in the 3 November presidential election. Barring unforeseen intervention by the judiciary, Joe Biden will take office as the 46th U.S. president in January.

At first glance, Biden’s electoral victory is a relief for the international community, which has reeled from the thunderclap of Trump’s 2016 upset win and the erratic, go-it-alone decision-making that has followed. Biden is a comparatively steady hand at the till and a known quantity. The former vice president has made a career by pressing the flesh with foreign leaders. This result is modestly reassuring in many European capitals, but it gives little reason for the international Syria response to celebrate. The incoming Biden administration is primed to dig in and recommit to the same open-ended time horizons and improbable objectives that have stalled in Syria as the conflict itself has drifted ever further beyond the reach of the international community. Aid actors and programmers dependent upon the U.S. security umbrella for access can breathe a sigh of relief, but they should be wary of getting what so many had asked for.

If and when Biden does take office, Syria will be an eighth-tier policy concern. Domestic matters are a more urgent priority, and the U.S. is likely to redirect foreign policy attention elsewhere, most notably China. Despite the considerable uncertainty that will remain long after Biden first returns to the White House, a range of outcomes can be expected for Syria and the international response.

The good

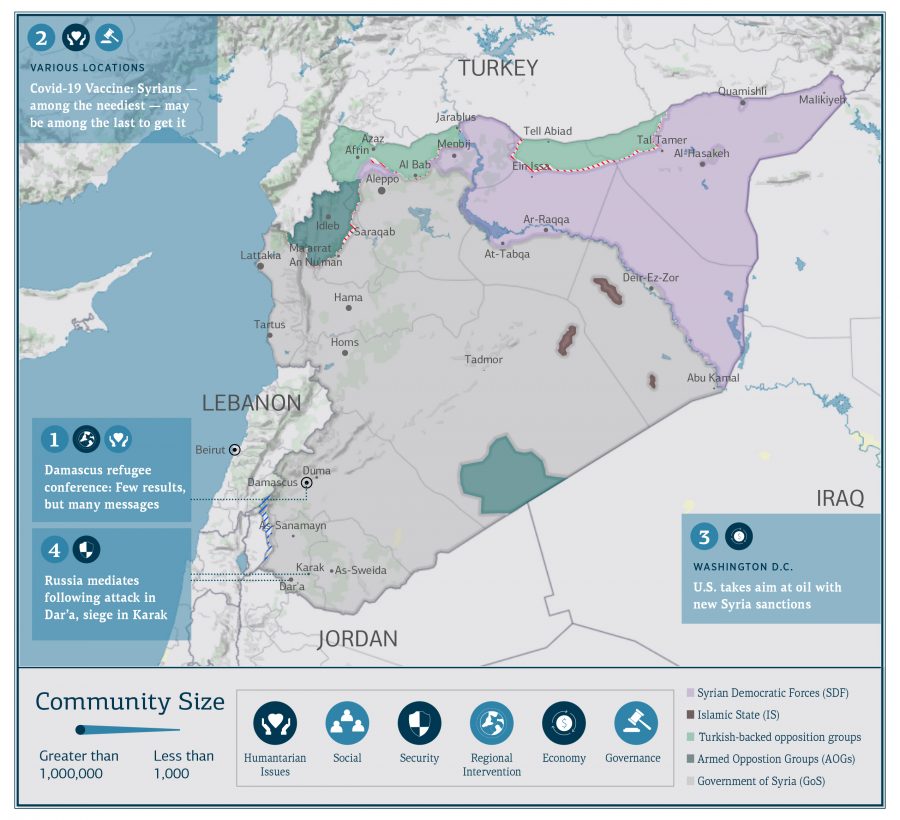

Biden’s victory is seen as a recommitment to the U.S. troop presence in northeast Syria. This will assuage the fears of aid actors who depend upon that presence as a guarantee for their own access. Biden’s win is also viewed as an indicator of tougher posturing against Turkey and President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in particular. Barring a complete fraying of Turkey’s relations with the U.S. and NATO, a repeat of Turkey’s Peace Spring incursion in northeast Syria is now less probable — but not impossible. It is not surprising that the Syrian Kurdish leadership was conspicuous in reaching out to the incoming administration. Biden’s victory will also reassure skeptical European donors burned by a Janus-faced Trump administration following its withdrawal in the northeast in October 2019. The Biden team will likely have better luck going hat in hand for stabilization assistance for northeast Syria, which is the clearest and perhaps most efficient point of leverage against Damascus. Efforts to combat ISIS and lord over eastern Syria’s oil bounty will also benefit the Self-Administration. In the long term, the emergent Kurdish polity will gain at Damascus’s expense, but in that respect, it will remain a means to an end — a partner, not an ally.

The bad

A Biden administration will likely decouple its Syria and Iran policies, yet what is good for Tehran may be bad for Damascus. Biden has pledged to re-enter the multilateral Joint-Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) — the “Iran deal” regarding Tehran’s nuclear program — in pursuit of detente. Syria has become a venue for U.S. policy designed to sap Tehran’s resources through maximum economic pressure, sanctions, and by trapping it in a Syrian quagmire. Yet there is no sign that a Biden administration will relent over Syria. The first iteration of the JCPOA clearly demonstrated that cooperation along the Washington-Tehran axis would not prevent confrontation by proxy elsewhere, including Syria. Even if Iran succeeds in winning concessions in exchange for a renewed commitment to the nuclear deal, the sanctions targeting Damascus that are already in place are unlikely to be rolled back, and more are expected in Trump’s remaining time in office.

The ugly

Biden is a status quo centrist. In the absence of a new vision, the incoming administration will likely play for extra time in Syria. Outgoing U.S. Syria envoy James Jeffrey recently described the standstill in Syria as a feature, not a bug, of “great power competition” over the country. “I think the stalemate we’ve put together is a step forward and I would advocate it,” Jeffrey said in counsel to the incoming envoy, Joel Rayburn. The operational stability that Biden will likely bring for aid actors is a grim omen for Syrians, who will be forced to endure longer still as already miserable conditions worsen. A long-time foreign policy adviser to Biden and a presumed fixture in his incoming administration has described the Caesar sanctions as a “very important tool” to shape outcomes in Syria. If the administration follows through as expected, Washington will not shelve the sanctions, the most wide-reaching cudgel it wields in Syria (see: Syria Update 22 June).

This is all the more troubling because international processes designed to wind-down the conflict, a prerequisite to sanctions relief and re-engagement, appear hopelessly deadlocked. The Syrian Constitutional Committee proceeding under UN Security Council Resolution 2254 has hit a brick wall. Other processes are also on life support. The Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons recently issued its 85th monthly report concerning the mandate to rid Syria of chemical weapons and investigate past attacks. Nonetheless, justice and truth and reconciliation appear as distant as at any time during the conflict.

Critically, there is time enough for Trump to flip the table on the incoming administration. Jeffrey recently boasted that American war planners have kept up U.S. troop levels in Syria through a “shell game” designed to bamboozle the president. There are “a lot more than 200” U.S. soldiers in Syria, Jeffrey said, referencing the limited troop commitment agreed to by Trump following serial threats to withdraw altogether. Other estimates range to 900. The revelation is poorly timed and risks antagonizing a president suspicious of a defense establishment he views as arrogant and hostile. Donald Trump has two months left in office. Firing the top brass at the Pentagon has removed institutional guardrails, and further sudden moves may render some or all elements of the next administration’s Syria strategy inoperable. In this respect, Washington is likely more unpredictable than Damascus in coming months. Indeed, on 13 November, Syria marked the somber occasion of 50 years under Al-Assad family rule.

In the longer term, the apparent ouster of Donald Trump will remove the volatile core at the center of dysfunctional international cooperation, including Syria policy. Yet stabilizing current conditions will do little to advance processes that have already reached a dead end. Europe itself does not present a unified front on Syria. Regional powers escaped the western orbit and began to pursue independent Syria policies long ago. Political detente between Gulf capitals and Damascus has already begun. Commercial trade is also picking up, albeit slowly. For a European policy community that is committed to preventing a mass refugee exodus from Syria, halting the export of violence, and upholding the rules-based order, Syria remains a vexing but critical arena. Biden campaigned on a pledge to “place America at the head of the table” internationally. Yet there is little reason to expect a new U.S. administration will advance the ball down the field unless, or until, international objectives in Syria are re-aligned and re-calibrated. A starting point will be to set goals that are amenable to incremental progress, rather than holding out hope for all-or-nothing grand bargains.

International objectives in Syria continue to reflect the prior assumptions of an era in the conflict when radical change appeared to be within reach. Political change has indeed come since the onset of the Syrian uprising in 2011, but the biggest changes have taken place outside Syria’s borders. Trumpism and the 2020 election have prompted many in the U.S. policy community to reconsider long-held sacred nostrums. Biden’s tenure will likely bring unforeseen impacts, including for Syria, yet there is a pervasive belief that the protracted conflict is one area where the former vice president will carry on with inherited policies that reflect conventional beltway consensus. There is space for new perspectives. There is also a need. Syrians will continue to feel the ill effects of policies that force them to endure as the international community carries on in search of objectives that are both politically palatable and realistic.

Whole of Syria Review

1. Damascus refugee conference: Few results, but many messages

Damascus: On 12 November, the two-day International Conference for the Return of Syrian Refugees concluded in Damascus, with the participation of 27 countries, and the UN, which was present as a “monitor.” Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad opened the conference (see: Syria Update 2 November) by declaring that his government’s capacity to support the return of millions of Syrians is undermined by Western sanctions and an economic embargo. “The issue of refugees return comprises three components: Millions of refugees willing to return; billions of dollars of damaged infrastructure; and terrorism still threatening a few areas,” he declared.

The conference had no tangible outcomes with respect to refugee return, yet it did showcase Russia’s preeminence in Syria. On 11 November, Mikhail Mezentsev, head of the Russian-Syrian Coordination Center for the Return of Refugees, announced that Russia would allocate more than $1 billion for “the reconstruction of the electricity networks, industrial and other humanitarian purposes in Syria.” Russian and Syrian institutions inked eight memorandums of understanding on the conference sidelines. The deals concern trade, education, and electricity generation. Furthermore, the first Russian agricultural company in Syria was established on 11 November, and it received authorization to invest in agricultural trade and operate dams and drainage networks. In parallel, on 11 November, Iran and Syria agreed to initiate a barter system between the two countries in which Syria will trade olive oil and lentils in exchange for sunflower oil from Iran.

Testing international waters or moving unilaterally?

The conference’s ambitious scale was overshadowed only by the farce of its underlying premise: For the foreseeable future, large-scale voluntary return to Syria remains unlikely. Not surprisingly, participation in the event cut along deep ideological divisions. Among major refugee-hosting nations, only Lebanon and Iraq participated, while most Arab and European states declined to attend. Participants were primarily nations that neither host Syrian refugees nor have the financial capacity to support returnees, such as Venezuela, the Philippines, Belarus, and North Korea. It is noteworthy that the United Arab Emirates, despite announcing its participation, was a no-show, reportedly due to U.S. pressure. The boycott by the U.S., EU, Turkey, and Jordan threw cold water on the massive returns program. Meanwhile, popular campaigns driven by Syrian refugees and civil society organizations stressed that many refuse to return under the current political, security, and economic conditions in Syria. As Syrian critics of the conference noted, bread lines in Syria are long enough without returnees.

On the other side of the ledger, the Syrian government has consistently failed to carry out the large-scale reconstruction works needed to facilitate the return of refugees, to say nothing of its ability to guarantee returnees’ safety and dignity. Rural Damascus Governor Alaa Ibrahim’s claim that returnees can find shelter in makeshift centers and IDP camps near Damascus is a compelling demonstration of the Syrian government’s tone-deafness on the issue, particularly when held against high-end residential development plans, such as the Grand Town scheme, exhibited on the sidelines of the conference.

Perhaps the conference’s most notable outcome is that it gives cover for Russia and Iran to assume greater control over the Syrian economy and vital service sectors. Rehabilitation of the electricity sector has not kicked off despite a previous Iranian MOU to take on the task (see: Syria Update 30 October-5 November 2019). Despite past failures on the electricity file, there is a risk that service sectors will be privatized and turned into cash cows for foreign investors — if and when Syrians have the opportunity to become reliable rate payers. At a glance, Russia’s reconstruction promise is generous, but it amounts to a pittance when compared with the $250-400 billion that will be needed to put Syria back together again. Nonetheless, the image of rubles pouring into Syria may send the message that reconstruction is now on. This is unlikely to spark spontaneous returns on any significant scale, but if other initiatives follow, it may inflame anti-refugee sentiment abroad and whet the appetite of would-be investors eager to stake out claims to rebuildable turf in Syria.

2. Covid-19 Vaccine: Syrians — among the neediest — may be among the last to get it

Various Locations: On 9 November, pharmaceutical firms Pfizer and BioNTech announced that their experimental COVID-19 vaccine was more than 90 percent effective in preventing symptomatic infection in initial large-scale trials. The news was a shot in the arm for those weary of life under lockdown, and it fueled hopes that a return to normal life is on the horizon. However, the international community is not out of the woods yet. There is significant ground to cover before the vaccine (and other candidates still in development) is available in sufficient quantities for immunization on a global scale, and the impediments to effective distribution are daunting. Provided the treatment does receive emergency regulatory approval, the firms can produce only 50 million doses this year — enough to immunize 15 million people — and a further 1.3 billion doses in 2021. Crucially, vaccination requires two doses be administered by a healthcare professional, spaced at least 21 days apart. Even when a cold storage chain (of minus 70 degrees celsius) is present, the vaccine has a shelf life of only 10 days.

Knock knock. WHO’s there (or is it?)

The logistics challenges to vaccination will be nettlesome, even in the most stable contexts. Syria is anything but. With spotty COVID-19 data, crumbling public healthcare infrastructure, and competitive, misaligned public health authorities, Syria poses daunting impediments to mass vaccination. Three main issues arise over the procurement and distribution of a COVID-19 vaccine in Syria.

Firstly, Syria’s tripartite division means that vaccine acquisition, distribution, and administration must be carried out by three competing governance entities, each with different actors, mechanisms, and agendas. Government of Syria-controlled areas will likely procure the vaccine via the World Health Organization (WHO), while storage, transportation, and administration will be the remit of the Syrian Ministry of Health (MoH). MoH exercises total control over the procurement and administration of vaccines in Syria and will likely impose its own criteria when setting vaccination priorities, irrespective of WHO guidelines or need. This protocol may pit the MoH against the WHO. The impact of this misalignment is magnified by the existence of the Sputnik V vaccine, which Russia has vowed to provide Syria, notwithstanding WHO’s claim that the drug remains experimental. If Moscow’s commitment to its vaccine extends beyond the propaganda value of its pledge, there is no preventing Damascus from distributing it across areas of its control, despite the protests of WHO. Should Syria find itself low on the priority list for vaccine distribution, the pressure to adopt alternatives will mount.

Areas outside government control also show a deep reliance on international backers. In northeast Syria, administrative approvals must be obtained from the Government of Syria due to long-standing health sector coordination. However, direct delivery to the northeast is theoretically possible without mediation of the WHO, the UN, or the Syrian government. Areas of northwest Syria under Turkish control are expected to be the most difficult, given that delivery of the vaccine is likely to take place through the WHO in Turkey. This arrangement has its own set of complications, given that the Turkish government may place a low priority on vaccination in Syrian territories where it does not yet have full control.

Secondly, logistical challenges that confound vaccine distribution in the developed world amount to nigh insurmountable barriers in Syria. The shambolic state of Syria’s infrastructure makes maintenance of cold chains extremely daunting, particularly given existing inadequacies to transportation infrastructure, healthcare centers, and the government’s own warnings that electricity provision will worsen in the coming winter months.

Thirdly, there are discussions among development and public health actors that COVID-19 has not yet hit areas affected by humanitarian crises as severely as many had anticipated. This surprise finding may impact international prioritization of vaccine delivery, including to Syria. This argument, however, is flawed in no small part because protracted crises also lack complete data and adequate testing; the data gap impairs efforts to identify impacts. Testing rates are also extremely low, and Syria’s coronavirus case figures are almost certainly severely underreported. Healthcare workers are unable to share data candidly for fear of reprisals or drawing unwanted scrutiny from authorities who view the virus as a security threat, rather than a public health challenge. The vaccine news is a welcome first step toward reclaiming a semblance of normality in public life, yet there is a distinct risk that Syrians — among the most vulnerable — will be among the last to enjoy its benefits.

3. U.S. takes aim at oil with new Syria sanctions

Washington D.C.: On 9 November, the outgoing Trump administration announced sanctions targeting several Syrian government-aligned business people, parliamentarians, and military and security officials. Among those sanctioned was, notably, energy tycoon and crossline trader Hussam Al-Qaterji, alongside head of Air Force Intelligence Ghassan, Jaoudat Ismail, head of the Political Security Directorate, Brigadier General Nasr Al-Ali, and head of the National Defense Forces (NDF), Saqr Rustom. The U.S. has also sanctioned the NDF directly for the first time. Meanwhile two Lebanese nationals and co-founders of the Lebanon-based Sallizar Shipping company were also sanctioned, as was Arvada Petroleum, a company owned by Hussam Al-Qaterji and his two brothers.

Consistently inconsistent

The latest round of sanctions takes aim squarely at Syrian oil production and the network of middlemen and brokers who grease the skids for Damascus. The Qaterji oil company has long been a focal point in the Syrian oil trade. In 2018, it was sanctioned for its role mediating oil sales between the Syrian regime and ISIS. The company has been awarded a large agreement to rehabilitate the Homs oil refinery. Qaterji-owned Arfada Petroleum and Sallizar recently won contracts to expand oil refining capacity by establishing the private Al-Resafa and Coastal Refinery companies (in Ar-Raqqa and Tartous, respectively). In January 2020, presidential decree granted Arfada an 80 percent stake in the new companies, while allocating 15 percent to the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Resources, and the remaining 5 percent for Sallizar Shipping.

Although the Qaterji company has been sanctioned since September 2018, the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) have continued to sell oil to the Government of Syria via Qaterji. While the U.S.-led International Coalition may pressure the SDF to crack down on oil sales to the Government of Syria, the crossline oil trade has played out to mutual benefit. New sanctions alone will not be enough to alter the SDF’s posture, but they may signal that pressure is also being applied in other quarters, particularly as Syria emerges from yet another fuel shortage.

Meanwhile, the targeting of high-ranking security officials, and the NDF and its leader Saqr Rustom on the fifth anniversary of a massacre in Douma is highly symbolic, but little else. Perhaps the foremost significance of new sanctions targeting these individuals lies in the fact that they had avoided being sanctioned earlier. The NDF, for instance, has been a key auxiliary to regular Government of Syria forces for years. Furthermore, while the U.S. has previously sanctioned the Afghan Fatemiyoun and Pakistani Zainebiyoun groups, it has stayed its hand and avoided sanctioning between 20 and 30 Iraqi Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) militias – officially part of the Iraqi military – that fight in Syria and which have outnumbered other Iranian-backed militias in the country (including Hezbollah).

In this sense, the symbolic nature of such “new” sanctions is reminiscent of the Obama administration’s sanctioning of the Syrian Army, Air Force, Navy, Air Defence, and Republican Guard for the first time in January 2017 — days before the end of its term and the beginning of the Trump era. To the extent that sanctions may be effective in pressuring the Syrian government to implement genuine political reforms, pressure has been inconsistently applied, whether under President Obama or Trump.

4. Russia mediates following attack in Dar’a, siege in Karak

Dar’a and Karak, Dar’a governorate: On 8 November, 4th Division forces armed with heavy weapons and tracked vehicles reportedly assaulted Dar’a Al-Balad from the south and southeast, and several civilians were killed in ensuing clashes between Syrian government forces and fighters affiliated with the Dar’a Central Committee. Local media reported that Russia interceded and pressed for a quick resolution. Relatedly, on 11 November, media and local sources reported that Syrian government forces surrounded Karak, in the eastern Dar’a countryside, and demanded that townspeople surrender the weapons they had seized from Air Force Intelligence personnel following a deadly raid days earlier. Among those killed in the raid was Lieutenant Colonel Suhan Hassan Othman, also known as Suhan Khader. Following negotiations and with Russian mediation, the 4th Division was allowed to search houses in Karak for weapons on the condition that there be no arrests.

Chaos continued

The flare-up in violence in southern Syria stands as further evidence that half-measures designed to pacify the region will end in failure and beget further instability. The incidents in Dar’a city came shortly after the Syrian government’s public release of 62 detainees and claims it had settled the status of more than 700 locals (see: Syria Update 9 November). As usual, the gestures were not a signifier of conciliatory posturing, but the growing impatience of Damascus, which nonetheless stopped far short of meeting the scale of popular demands. The assault on Dar’a Al-Balad puts further pressure on continuing efforts to boost the negotiating leverage of southern Syria. Talks to form a unified negotiating platform across the south continue, but they have suffered setbacks, including the assassination of prominent interlocutor Ahmad Al-Krad (see: Syria Update 19 October).

The events also cast light on Russia’s unhappy role as regional mediator. Following the siege and clashes of Karak and south-east Dar’a, Russian negotiators were once again called in to mediate. Although Russia’s regional ambition likely remains the extension of its uniform security umbrella over armed groups in eastern Dar’a, its ability to keep the peace has been limited, and its negotiated settlements have had a limited shelf-life. A 12 November IED attack targeting a Russian vehicle near Mseifra, in eastern Dar’a, is evidence that Russia’s courting of former opposition fighters has made it enemies as well as friends. At the time of writing, no one has claimed responsibility for the IED, which echoes a similar incident in July 2019. Future incidents remain possible. For the Syrian government, the brief siege of Karak may achieve a triad of outcomes. First, it disarms the community. Second, it resupplies loyalist forces. Indeed, locals were made to hand over weapons and more than 200,000 rounds of ammunition. Third, it sends an unmistakable message about the state’s willingness to use force — even if those responsible for the attack on the Air Force Intelligence personnel had already fled, as local sources indicate.

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below.

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

Biden’s victory revives hopes for a change in US policies towards the Middle East

What Does It Say? The report reviews the myriad ways the U.S. election result will affect the Arab world.

Reading Between the Lines: Communities the world over are speculating how Biden’s foreign policy will differ from that of Trump. In the Middle East, with the notable exception of Iran detente, Biden will likely stay the course. As a status quo institutionalist, Biden gives few signals of an impending break with decades-old norms.

Source: Carnegie

Language: Arabic

Date: 10 November 2020

The Syrian Red Crescent receives the fourth shipment of UAE medical aid

What Does It Say? An aid shipment for the COVID-19 response arrived in Damascus overland via the UAE.

Reading Between the Lines: The delivery is notable both because it followed the overland route vital to Gulf commerce with Syria and because it signals the UAE’s continuing openness toward the government in Damascus.

Source: Damascus SV

Language: Arabic

Date: 9 November 2020

Number: Revenues of private banks in Syria during the first half

What Does It Say? The article outlines private banks profits, which jumped in the first half 2020, compared with 2019.

Reading Between the Lines: The report gives little cause of celebration; Syria remains locked in a deep and serious financial death spiral.

Source: Al Iqtisadi

Language: Arabic

Date: 11 November 2020

SDF arrest four ISIS members in rare raid in eastern Syria’s Deir al-Zor

What Does It Say? In a joint operation, the SDF and the U.S. Coalition arrested four ISIS members in rural Deir-ez-Zor.

Reading Between the Lines: Long after the demise of ISIS, sleeper cells associated with the group continue to pose a threat. Many in the defense establishment view this issue with growing urgency.

Source: Kurdistan 24

Language: English

Date: 8 November 2020

Russia announces it: We have tried all the Russian weapons and forces in Syria

What Does It Say? The Russian defense minister has announced that all Russian weapons will be tested in active combat in Syria.

Reading Between the Lines: The announcement certifies an open secret: that Russia has used Syria as a proving ground for weapons systems that it hopes to refine for the use of its own armed forces and peddle on the open market.

Source: Al Wakale

Language: Arabic

Date: No date

What Does It Say? Russia has allocated funds for reconstruction in Syria for multiple sectors following the refugee conference in Damascus.

Reading Between the Lines: The agreement is the most concrete outcome of the conference, and it gives a wide berth for Russia to maintain a deep hold over the Syrian economy — including through basic service privatization — long into the future.

Source: RT Online

Language: Arabic

Date: 11 November 2020

Close to Assad: Disclosure of personalities involved in drug trafficking for Hezbollah

What Does It Say? The article claims that high-ranking Syrian officials have been working with and protecting Hezbollah drug smuggling activities occurring en route to the Gulf.

Reading Between the Lines: The claims suggest complicity in drug smuggling at the upper echelons of the Syrian ruling class. Given the lucrative nature of drug activity in Syria’s otherwise shattered economy, it is unlikely they will give it up.

Source: SY 24

Language: Arabic

Date: 10 November 2020

What Does It Say? The WHO has provided continuous support in combating COVID-19 in Syria.

Reading Between the Lines: Conflict conditions, the economic situation, and sanctions have made Syria acutely vulnerable to the effects of the pandemic. The country lacks the tools needed to contain the disease, which it continues to treat as a security risk rather than a threat to public health.

Source: United Nations News

Language: Arabic

Date: 9 November 2020

The Dynamics of Refugee Return: Syrian Refugees and Their Migration Intentions

What Does It Say? The study finds that Syrian refugees in Lebanon would rather stay put — despite the deteriorating situation in Lebanon — because it remains more favorable than tenuous conditions inside Syria.

Reading Between the Lines: The findings should not be a surprise. Although most Syrians express a general desire to return, the Syria they wish to return to does not — and likely never will — exist. The push factors that drove them into flight from Syria remain unresolved.

Source: SocArXiv Papers

Language: English

Date: 8 November 2020

How a French Charity Built Ties with Pro-Assad Christian Militias

What Does It Say? A Christian French Charity has been providing aid to Christians in Syria and has built ties with militias tied to the Syrian state. These militias have been accused of war crimes.

Reading Between the Lines: The charity seems to regard its efforts not as principled humanitarian work, but as a divine obligation to stabilize Syrian Christians in Syria, whatever the collateral costs.

Source: Bellingcat

Language: English

Date: 4 November 2020

The Wartime and Post-Conflict Syria project (WPCS) is funded by the European Union and implemented through a partnership between the European University Institute (Middle East Directions Programme) and the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR). WPCS will provide operational and strategic analysis to policymakers and programmers concerning prospects, challenges, trends, and policy options with respect to a conflict and post-conflict Syria. WPCS also aims to stimulate new approaches and policy responses to the Syrian conflict through a regular dialogue between researchers, policymakers and donors, and implementers, as well as to build a new network of Syrian researchers that will contribute to research informing international policy and practice related to their country.