This is the second in a series of papers intended as primers on understudied aspects of Syria’s profound economic deterioration. In nearly a decade of unrest, Syria has been reduced from a liberalizing middle income nation to a failed state in which 90 percent of the population is mired in poverty. In response to this daunting reality, the papers in this series look beyond conventional econometrics and humanitarian orthodoxies to provide clarity and identify new insights for humanitarian and development actors. The first paper in this series is available here: The Syrian Economy at War: Armed Group Mobilization as Livelihood and Protection Strategy.

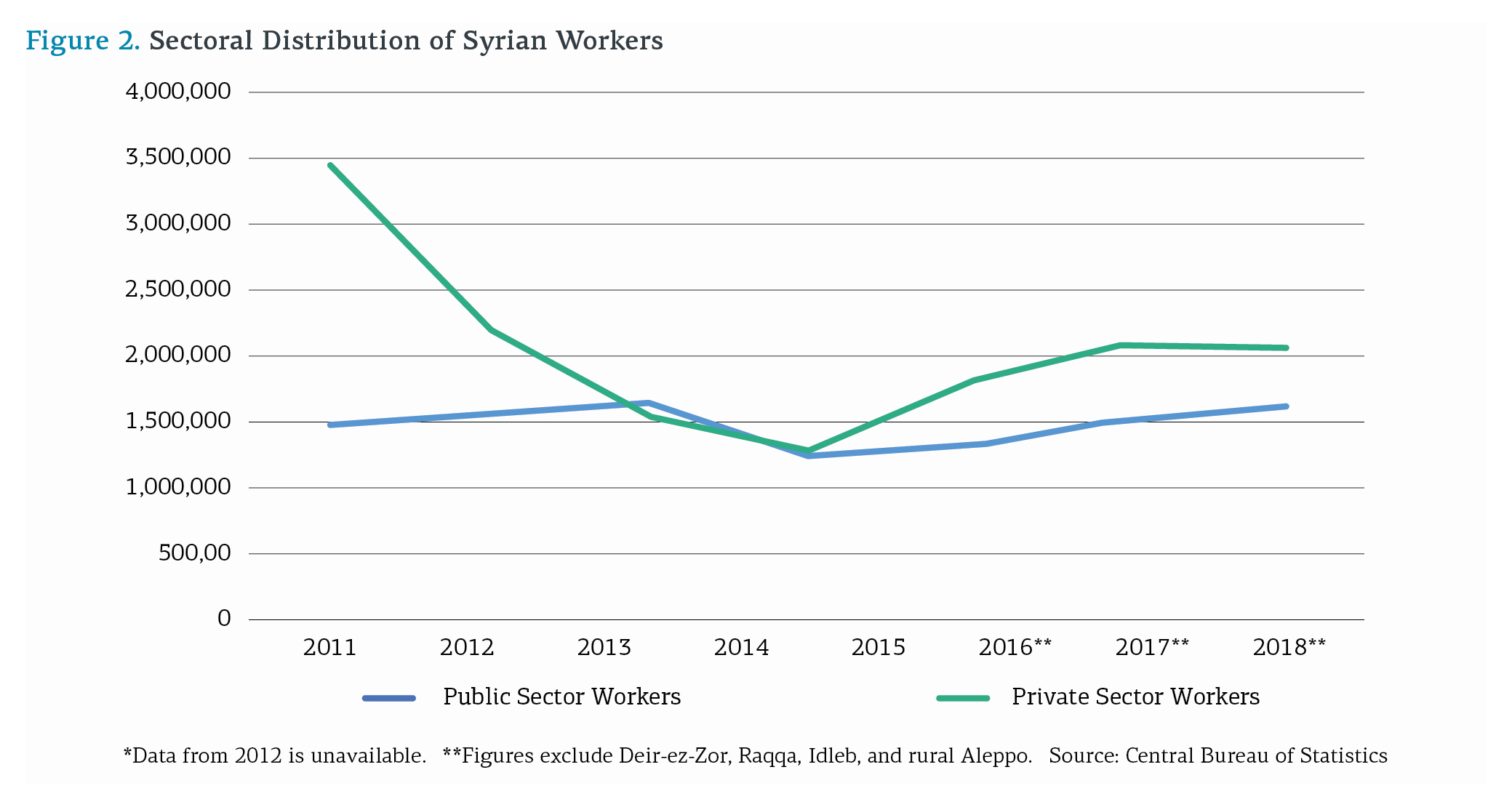

The conflict in Syria has been a rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight. War profiteers and crony businessmen have enriched themselves as ordinary Syrians have carried out the actual fighting. Although some areas of the country are transitioning away from active conflict, state and economic collapse are inescapable realities that must be confronted. Once again, the worst effects are being shouldered by ordinary Syrians. Almost universally, the population has suffered as the Government of Syria has progressively abandoned its traditional responsibility for labor costs and social support, which has dwindled even as inflation erodes the real value of wages. Public sector salaries would need to grow by a staggering 420 percent to keep workers’ purchasing power on a par with 2010 levels. The unemployment rate stands at an estimated 42 percent, and the labor force has shrunk to 3 million workers, down from 5.2 million in 2011.[1]State employment figures are not available for 2019 or 2020. See: “Justice to transcend conflict: Impact of Syrian conflict report” Syrian Center for Policy Research (2020): … Continue reading As a result of these realities, Syrian workers arguably face greater economic jeopardy than at any point in living memory, and conditions are likely to worsen.

This paper assesses public and private sector labor dynamics in government-held Syria to identify the most pertinent challenges facing the Syrian labor force. These are, ultimately, challenges for the Syrian population as a whole. Almost universally, wages have slipped below sustainable levels, forcing even top-earning public employees to seek out supplemental income. Job security and contracting terms are no longer surefire incentives for public sector work, and de facto restrictions have trapped many public employees in dead-end jobs. Among private sector workers, few labor guarantees exist, particularly as unaccountable foreign corporations capitalize on state collapse to enter the Syrian market. Collectively, these conditions are a foremost concern for the international Syria response. As the protracted crisis evolves, Syria’s deep economic instability has given rise to new complications for aid actors, but potential programming opportunities are apparent, too.

Key Takeaways

-

- The Syrian state has contained social support costs by eliminating subsidies, checking salaries, and transferring labor, administrative, and infrastructure expenses to the private sector or to the population itself.

- Public sector salaries are a vital lifeline for workers which protects against outright destitution. However, the wage ceiling is low. No public sector salary in Syria covers the cost of living in Damascus. The official salary of a Syrian MP (approx. $52) is now below the global poverty level, $1.90 per day. Ordinary workers are significantly worse off, and many resort to negative coping strategies.

- Systemic hurdles to resignation lock public workers into dead-end jobs with untenable salaries.

- In some sectors, public employees supplement meager state wages with private sector labor. Dual-practice allows workers to make ends meet, and it enables the state to retain skilled technicians while transferring costs to the private sector. Absent this flexibility, public workers would likely be more reliant on illicit revenues, including from bribery and corrupt practices. Service quality would also degrade, and whole industries would be at greater risk of outright collapse.

- Private sector workers enjoy fewer labor rights than their public counterparts. Privatization allows investors to roll back labor protections, and influential foreign investors — primarily Russian firms — operate formerly state-owned enterprises with virtually unchecked impunity.

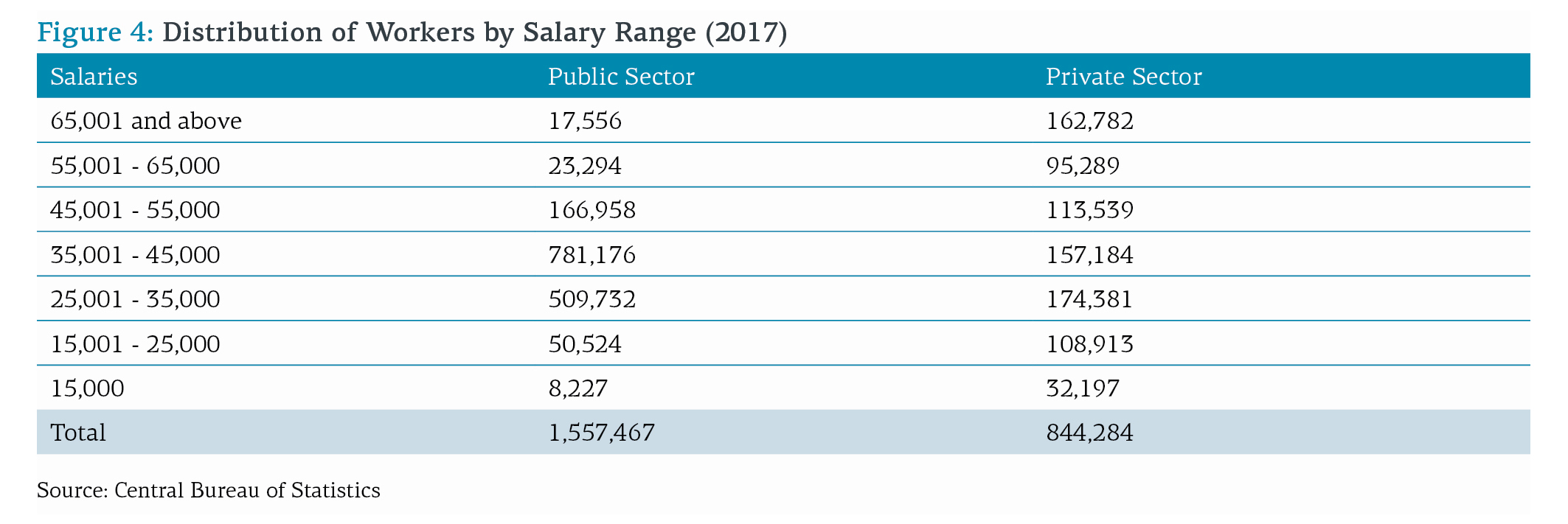

- The private sector wage scale is uneven. A small tranche earns generous salaries many times greater than public sector counterparts, while most private sector workers earn far less and enjoy fewer wage guarantees than public workers.

- The collapse of social support networks, state service provision, and meaningful labor guarantees challenges the social contract that binds the Syrian state and labor power — and in many ways the population itself. Piecemeal economic privatization, particularly agreements that put lucrative state assets under foreign management, undermine the state’s capacity to maintain this balance, thereby challenging its legitimacy and hampering future efforts to restore the rule of law and good governance.

Action Points

-

- Aid actors must view worsening livelihoods and labor conditions as a priority need that is likely to worsen over time.

- Adverse labor and livelihoods conditions are a result of systemic collapse. Sustainable wages will not return organically or on a large scale until Syria’s economy recovers — likely years after an end to active conflict. Humanitarian and development activities must approach these realities with long-term perspective.

- Aid organizations must be aware of shifting wage scales and prepare to adjust compensation accordingly. Yet simply paying more is not always the answer. Throughout the conflict, humanitarian organizations have frequently distorted local labor markets by offering salaries that are significantly above going rates. It is important to balance the need to provide a living wage with the imperative to avoid incentivizing the flight of skilled workers from service sectors or state enterprises.

- The private sector will have to complement the deficiencies of the state. This will create likely entry points for aid activities and donor-funded support.[2]COAR has explored Syria’s “gap economy” and the relevant entry points for locally driven development and donor-funded aid activities in detail in previous thematic papers. The stability of … Continue reading Filling gaps and stabilizing locally responsive actors, including small and medium enterprises, may provide a means of meeting community needs.

Pressure Points: Public Sector Privatization and Worker Risks

A History of (Economic) Violence

The Syrian economy is often conceptualized as a marriage of convenience between the ruling Al-Assad regime and a small inner circle within the Syrian business community. In simplistic terms, it is generally understood that business elites, regime loyalists, [3]Notably, in his book Business Networks in Syria: The Political Economy of Authoritarian Resilience (2011), Bassam Haddad argues that since the 1970s, there was a growing alliance forming between … Continue readingand security actors trade fealty in exchange for preferential access to new economic opportunities.[4]Joseph Daher, “The political economic context of Syria’s reconstruction: a prospective in light of a legacy of unequal development”. Middle East Directions (2019): To an extent, these relationships have existed since the emergence of the modern Baathist state in the 1970s. However, the significance of these processes has grown under the liberalization policies introduced by Hafez Al-Assad in the mid-1980s and carried on by Bashar Al-Assad in the early 2000s. Syria’s previous strides toward economic privatization were driven in part by the need to maintain a tight grip on critical economic files as the state itself divested from the national economy, and they resulted in state capture, patronage, and monopoly.[5]Two main outcomes were apparent. First, by instrumentalizing the state apparatus in this way, the regime channeled attractive positions to its allies and dependents. Second, privatization ensured … Continue reading Now, pre-conflict features of Syria’s emerging market economy remain, but their continued evolution has brought new pressures to bear on the Syrian labor force.

Labor and the Sinking Ship of State

The government remains the largest single employer in Syria. Not all public jobs are created equal, however. Syria’s public sector labor force can be divided into two broad camps, each of which faces unique challenges from the shifting political economy of Syrian labor: public servants and public enterprise employees. Public servants are state employees working in administrative and service-oriented positions (i.e. health, education, councils, etc.). Public servants constitute approximately 56 percent of the public sector labor force as of 2018, the latest data available. These workers constitute the backbone of the state. On the other side of the ledger are public enterprise employees, state workers within productive sector industries (e.g. extractives and manufacturing). They numbered approximately 700,000 workers in 2018.[6]The Central Bureau of Statistics does not clarify which workers are included in this number, although it likely excludes figures for the Ministry of Defense, whose data remains classified. These employees are at greater risk of job loss due to the atrophy of the state.

Three interlocking dynamics create unique pressure points for public employees of all types: salaries, contracts, and privatization. Pay raises have been inconsistent, and currency depreciation and market inflation have significantly diminished purchasing power. Contracts no longer offer vital job security, and for many workers, restrictive contracts are an impediment to higher-wage labor opportunities in the private sector. Finally, privatization is itself a threat to public employment, which remains a lifeline and a wage floor for many state workers. While some private sector workers enjoy a considerable salary premium, most earn far less, and they enjoy fewer worker protections.

Salaries: Catching Up and Falling Behind

Throughout the conflict, the share of the state budget[7]“2020 Budget Expenses – Full Details,” The Syria Report (2020): https://www.syria-report.com/library/budgets/2020-budget-expenses-full-details allocated to paying salaries has risen progressively as the state has amended public-sector pay scales on five separate occasions.[8]Since 2011, there have been five official salary increases that were offered by the state to public sector workers and retirees: In 2011, 2013, 2015, 2016, and most recently in late 2019. Over time, salary raises and social spending have become increasingly untenable for the state. Budget growth has stagnated and lagged behind social support costs and wages due to diminished productive output, currency collapse, and the near-total cessation of the exports needed to shore up foreign currency reserves. The Government of Syria has therefore struggled to sustain its budgetary commitments, and fulfilling obligations to workers has left Damascus less capable of meeting other needs, including investments in and rehabilitation of enterprise activities, the provision of essential services and subsidies, and the import of energy products and grain.

These conditions have forced workers to shoulder a greater burden directly. In the first instance, despite nominal wage growth, public sector salaries have declined significantly relative to the cost of living. The most recent state salary increase in November 2019 raised the base pay at the uppermost tier of the public sector scale to 80,240 SYP (approx. $96 at that time). The same salary now amounts to $30.74. Meanwhile, by October 2020, the average cost of living in Damascus for a family of five reached 660,000 SYP (approx. $263 at that time) per month.[9]“The Living Costs for a Family of 5 in Damascus,” Kassioun (5 October 2020): https://kassioun.org/economic/item/65798-660-5-2020 (AR). This points to a staggering reality: Not a single public sector salary in Syria approaches the actual cost of living in the capital. At 139,000 SYP ($52), even the salary of a Syrian MP falls below the global poverty level of $1.90 per day.[10]“Poverty,” World Bank Group (2020): https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/overview. Naturally, the conditions facing ordinary workers are even more jarring. In parallel, the reduction in subsidies and a series of increases to the prices of strategic commodities such as fuel have placed greater shares of the state’s subsidy costs onto consumers, either directly or through trickle-down effects such as rising public transport fares.

To cover the resulting gaps, workers have been driven to negative coping strategies such as a reliance on foreign remittances, savings, and supplemental labor income, which is often intermittent and poorly paid, if it can be found at all. Some workers are able to supplement meager state salaries through dual-practice in the private sphere. However, many public servants have few options to trade on their job skills. Bureaucrats routinely demand bribes to transact ordinary government business. This adds to the cost burden created by exorbitant fees required to access property documentation, civil registry filings, passports, and other routine administrative processes. In practical effect, economic malaise has reduced Syria’s civil bureaucracy to a system of fee-based governance, and state apparatuses and civil servants alike treat service-seekers as sources of revenue.

Contracts: A Binding Labor Agreement, Or a Legal Bind for Laborers?

Prior to the conflict, job security was among the chief attractions of state employment in Syria. Yet not all state workers enjoyed firm benefits, then or now. Workers on short-term and zero-hour contracts have reduced access to social security and health insurance. They are often worse-compensated, and most importantly, their job security is extremely limited. [11]“Thousands of temporary workers waiting for decades for their contracts to be fixed,” Syrian Economic News (18 March 2019): https://sensyria.com/blog/archives/32043 (AR) and “The story of daily … Continue readingFor instance, in July 2020, Damascus governorate officials refused to renew the contracts of more than 1,000 workers employed on short-term contracts, a decision they justified on the basis of funding shortfalls.[12]“Governor of Damascus resolves the issue of daily workers,” Al-Baath Media (2020): (AR). However, in response to heavy criticism, Governor of Damascus Adel Al-Olabi reversed course on the decision, a rare acquiescence to labor demands.

In current conditions, more stable fixed-term contracts also expose state workers to unwelcome pressure. Law 50/2004 makes it virtually impossible to dismiss civil servants, but the job security this entails cuts both ways. In reality, the job guarantees also prevent many workers from leaving dead-end jobs with untenable salaries. Workers seeking to resign due to poor state pay[13]“High cost of living pushed public sector workers to resign,” Bawaba Syria (2020): (AR). must navigate arbitrary security and administrative obstacles imposed by intelligence and ministerial agencies. Resignation petitions are often rejected. Syrians who flee the country in violation of a public labor contract risk severe punishment upon return. As the state seeks to offload labor and social support costs, it can be expected that barriers to resignation will be eased for some portions of the public sector workforce. This will not take place uniformly, and it is likely that enterprise workers, whose jobs can more easily be privatized without undermining the state bureaucracy, will face fewer hurdles than public servants, whose experience and ingenuity are needed now more than ever.[14]However, the state has contemplated the privatization of national health insurance.

Although options are limited for many classes of professionals such as architects and engineers, healthcare workers are among the public employees who regularly earn significant supplemental labor income through dual-practice activities.[15]Efforts by the state to offset the public healthcare sector to private businesses and investors were not halted there. By the end of 2019, the Government of Syria considered establishing a private … Continue reading Physicians and medical specialists often operate private practices and serve in non-public institutions (including NGO-supported facilities). This practice was common prior to the conflict; however, reliance on non-public health capacity has grown due to the flight of healthcare workers, the forced evacuation of medical professionals from reconciled communities, and the significant damage to public hospitals across much of Syria. In effect, the piecemeal privatization of healthcare has allowed the state to circumvent the need to make investments in workers, health infrastructure, and facilities. Seventy-seven percent of hospitals (359 in total) in government-held areas are private, according to Ministry of Health and WHO data from 2019. In Damascus, 75 percent of hospitals (61 in total) are private. Were it not for this dual-practice flexibility, such services would likely degrade or cease altogether.

Privatization: The Other Side of the Ledger

In addition to the salary and contracting pressures facing state workers, privatization itself is a challenge that foreshadows the continuing elimination of state jobs, particularly for enterprise workers. Privatization in wartime Syria is a story that has unfolded in two acts. As the early years of the conflict progressed, private employment declined sharply. Despite the pitched loss of private jobs, the state engaged in a crisis management strategy to retain public workers, even in opposition-held areas. Doing so demonstrated Damascus’s sole legitimacy and denied rival civil entities access to experienced public workers. In 2010, public work accounted for 27 percent of jobs in Syria. Public employment peaked at 52 percent circa 2014, as the conflict closed in on what was, from the perspective of Damascus, its nadir. The year 2015 marked a decisive turning point. The Russian military intervention that year turned the tide of the conflict, and it became the beginning point for the measured rebound of the private sector and the relative stabilization of public sector work. State employment subsequently levelled off as a share of the overall workforce and settled around 44 percent by 2018, the latest year for which data is available.[16]In 2014, public sector workers dominated the labor force and represented more than half of all employment. Similarly, data from the Central Bureau of Statistics show that even after 7 years of … Continue reading

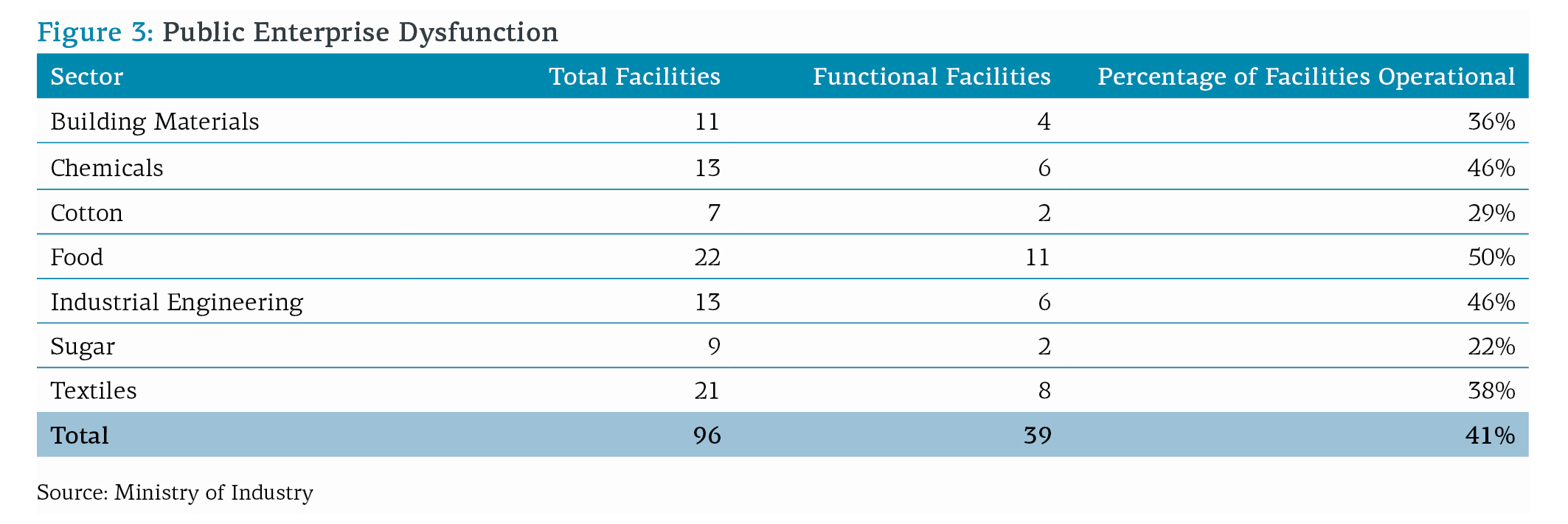

Looking ahead, the Syrian government faces less pressure to wield labor guarantees as a lever to assert political legitimacy, given that Damascus’s notional authority is not seriously challenged in areas under government control. Conflict destruction and the dysfunction of state-affiliated factories mean that future labor force growth will likely be concentrated in the private sector. Not only would this revert to the pre-conflict trend of economic privatization, it would reflect the reality that state enterprise as a whole has been heavily battered. In the best-performing industrial sector overseen by the Syrian Ministry of Industry, only 50 percent of institutions are functional. Among those in operation, output is likely hampered, and the state does not have the capacity to invest in state-run enterprises.

Piecemeal economic privatization is likely to fil the resulting gaps. From the perspective of some workers, this will yield benefits, but it will also widen economic inequality. Public workers are concentrated overwhelmingly near the center of the pay scale. More private sector workers earn above-average salaries, but far more also earn less than average. In 2017, fewer than 4 percent of public employees fell in the bottom two tiers of the wage scale, according to the Central Bureau of Statistics. Nearly 17 percent of private sector workers landed in the same categories. Labor opportunities will be limited until Syria’s overall market outlook demonstrates the stability needed for sustained, long-term private investment and economic growth. Until this transpires, the stability of the public sector will be paramount, despite its manifest shortcomings. Workers continue to depend upon the state to provide a wage floor while other opportunities remain scarce. As foreign companies and Syrian private investors tighten their grip on sectors vacated or purposefully surrendered by the state, wage and employment guarantees and associated benefits will weaken. Some workers will benefit, but many are likely to lose out.[17]This is also true of the militarized economy. Private military companies and foreign military powers have made inroads recruiting Syrians in part through attractive salaries, yet the scale of these … Continue reading

Private Sector Workers

A chief outcome of Syria’s economic triage is the privatization of strategic key industries, which has gone forward despite the slow recovery of the private sector overall. Prior to the conflict, the Syrian private sector accounted for 60 percent of GDP, 75 percent of total imports, and 56 percent of non-oil exports, according to the government’s 10th five-year plan.[18]Tatjana Chahoud, “Syria’s Industrial Policy.” German Development Institute (2011): https://www.die-gdi.de/uploads/media/Syrienstudie.engl.arab.pdf Today, the private sector accounts for nearly 56 percent of the Syrian workforce, mostly self-employed workers. A centerpiece of Syria’s economic privatization is the 2016 Public-Private Partnership (PPP) law, which allows private sector businesses to manage state assets in almost all sectors of the economy, apart from oil. This has further increased the involvement of crony capitalists and private business figures in affairs once firmly under the purview of the state. Current economic privatization has favored two types of sector actors: Syrian businessmen and foreign investors.

Syrian Privatization

The Syrian state has long turned to private businessmen to fill economic gaps. Entrusting economic and industrial power to loyalists was a hallmark of the liberalization policies of the early reign of Bashar Al-Assad. This process widened the ruling regime’s influence by creating mutual interdependence between central authorities and the direct beneficiaries of corporate privatization. Fundamentally, this process continues today, albeit through evolving means.

The dysfunction of state-run industry (see: Figure 3) creates clear gaps that can be filled by private actors, as many have done throughout the conflict. In narrow cases, the retreat of the state has sometimes played out to the benefit of local communities, but it has often facilitated elite capture and eroded service quality. The state has also purposefully shuttered institutions in a way that creates opportunities for local businessmen — particularly those with linkages to the regime — to monopolize services and infrastructure in transitional and post-conflict Syria. For instance, in 2019, under the directive of the Syrian Cabinet Economic Committee, the Syrian General Organization for Sugar ordered the shutdown of the sugar beet factory in Tal Salhab, in Hama governorate, prompting protest among farmers.[19]The General Organization for Sugar is a part of the Ministry of Industry, and it has factories and manufacturing companies for sugar and yeast in Homs, Al-Ghab, Tal Salhab, Maskanah, Al-Raqqa, … Continue reading The decision was justified on the basis that the sugar beet harvest fell short of the levels needed to operate the factory sustainably, leading the General Organization for Sugar to incur heavy losses in the previous two years, estimated at 6.567 billion SYP ($2.4 million). Although it is unconfirmed, there are particularly reports of collusion over the factor with Tarif Al-Akhras, a Syrian businessman and uncle of Syria’s first lady, Asmaa Al-Assad. Al-Akhras owns several sugar refineries, flour mills, a cornstarch manufactory, and multiple other industrial facilities. Reports have circulated that Al-Akhras intends to invest in several sugar factories that have shut down throughout the conflict, including the Tal Salhab factory.

Foreign Privatization

What is most notable about current privatization dynamics is that certain industries have been completely turned over to foreign investors, apparently in recognition of the military and economic assistance of external military allies. Russia has been the biggest winner by far. The Moscow-based conglomerate Stroytransgaz has made substantial investments in Syrian industries that were heretofore under the purview of the state. In 2017, the company signed a contract with the Syrian Ministry of Petroleum and Mineral Resources that allows it to extract and sell phosphate from Khneifis and Sharqiyah mines near Palmyra for 50 years.[20]“Moscow collects its spoils of war in Assad’s Syria,” Financial Times (1 September 2019): https://www.ft.com/content/30ddfdd0-b83e-11e9-96bd-8e884d3ea203Stroytransgaz will reportedly net 70 percent of the profits, leaving the Syrian state the meager remainder. In 2019, Stroytransgaz won contracts to manage the country’s sole fertilizer production facility, the General Fertilizers Company in Homs, and to manage Syria’s foremost commercial port in Tartous. As with the phosphate deal, the 2018 contracts promised the Russian firm the lion’s share of the profits, in addition to significant non-monetary assets such as control over wheat silos adjacent to the shipping terminal.[21]For more information on Stroytransgaz’s investment in Syria’s post-conflict economy see: “Factsheet: Stroytransgaz in Syria,” The Syria Report (6 April 2020): Further deals are expected.

Iran has enjoyed less commercial success. Months prior to the Russian phosphate deal, Iran signed an agreement with Damascus that would allow Iranian companies to develop phosphate mines in Sharqiyah. However, shortly after Tadmor (Palmyra) was retaken by Syrian government-affiliated forces, the Sharqiyah phosphate mine was instead turned over to Stroytransgaz. Multiple deals between Damascus and Tehran to rehabilitate Syria’s electricity grid in a bid to collect user fees have proved abortive. Iran also announced plans to initiate its own port at Lattakia to rival that managed by Russia, but this has foundered as well.[22]For more information on Iran’s investment in Syria’s post-conflict economy see: “Revolutionary Guards Get Hold of Syrian Mobile Phone Licence as Part of Broader Tehran Grab on Economic … Continue reading In the meantime, Tehran continues to harbor ambitions of converting Syria into a stable export market for Iranian manufactures, which recalls the same marketing conditions that dampened Syria’s industrial output prior to the conflict.[23]For instance, in October 2020, Iran established a large commercial centre in the Damascus Free Trade Zone named ‘Iranian’ which is projected to facilitate trade between Syria and Iran and build a … Continue reading

The Narrow Space for Syrian Labor

Neither Syrian nor foreign private investment has fundamentally altered labor dynamics in Syria, but they have put the impotence of the Syrian government on full display, as authorities have failed to intervene in support of Syrian workers despite the threat posed to core constituencies. Across industries, the space available for collective labor action and protests in government-held Syria is extremely narrow. Historically, the Government of Syria has suppressed labor activism, manipulated formal workers’ organizations, and instrumentalized such entities as arms of the state. All formal labor unions in Syria must be affiliated with the General Federal of Trade Union Workers (GFTUW), which is heavily influenced by the Baath Party. To a large extent, organized labor has been transformed from a vehicle for collective action and worker solidarity to an instrument to manage popular legitimacy and exercise political control.

As in the public sector, the space for organized labor action in foreign-owned facilities is limited. Under Syria’s private business framework, namely Law 17/2010, private workers enjoy fewer hard rights and less sweeping protections than equivalent public-sector laborers. Even Syria’s state-aligned national-level labor entity reached this conclusion in a 2020 study, which found that, almost universally, private sector workers are denied basic labor rights stipulated under Law 17, such as salary increases, health insurance, and social insurance.[24]“Regime Government Amends Private Sector Labour Law,” Tishreen (13 March 2019): https://bit.ly/2N326Ov. These conditions applied across sectors, except for workers in finance and insurance, according to the Labor Observatory for Research and Studies, the GFTUW’s research arm.

Although Law 17 extends formal labor protections to the thousands of workers at public facilities acquired by foreign investors, organized challenges to management remain perilous. For instance, in August 2020, workers at the Homs General Fertilizer Factory staged a demonstration demanding the release of several workers who were detained by the facility’s Russian management. The workers were reportedly held inside the factory as others refused to return to the job site following the discovery of a noxious gas leak, which was linked to several cases of asphyxia in neighboring communities. Though investigations were undertaken, factory management detained striking workers. Similarly, a long-running labor dispute between Tartous Port workers and Stroytransgaz administrators resulted in a managerial decision to dismiss several thousand staff, effective early 2021.

Both stand-offs highlight the limitations of labor rights, and they cast light on the perilous working conditions and adverse environmental and community impacts of Syria’s remaining industrial activity as foreign investors seek profit in Syria. In neither case were workers able to win major concessions. However, the protests highlight the adverse working conditions and livelihood concerns that are almost certain to create flashpoints in post-conflict Syria. Labor conditions, basic services, and local administrative and environmental issues are among the key drivers of nationwide grassroots civic engagement, including nominally apolitical protests. These pressures will be amplified in the future by continuing downward economic pressure.

The Social Contract

Ultimately, the shifting political economy of labor threatens the social contract that undergirds the modern Syrian state itself. In exchange for reliable services, consistent social support, labor guarantees, and basic security, Syrians have — willingly or otherwise — foregone political liberties and credible democratic institutions. The collapse of social support networks, state service provision, and meaningful labor opportunities complicates the relationship between the Syrian populace and the state. Looking ahead, the rebound of the private sector will be vital to fill gaps vacated by the state, yet unrestrained economic privatization will undermine the state’s capacity to meet its obligations to citizens. This is particularly true of agreements that put valuable state assets under foreign management, offshoring the profits extracted from Syria’s natural resources as repayment for war debts. For the foreseeable future, the Syrian state will remain a vital economic player, likely the largest and most important in the country. Undermining Syria’s future economic base will have a profound impact on the state’s capacity to restore efficient governance and service provision, to say nothing of its ability to provide needed social support and labor guarantees. Aid reliance will persist in the long term as a result, and the state will struggle to meet the myriad demands of the exhausted populace. For workers, few vehicles of meaningful dissent now exist.[25]It has been posited that a conceptual ultimatum confronts consumers in the face of deteriorating quality of goods: either exit or voice. To exit is to withdraw from the relationship (i.e. to … Continue readingAlthough the Syrian government has lost the capacity to supply carrots, the robust security state retains sticks aplenty.

References[+]

| ↑1 | State employment figures are not available for 2019 or 2020. See: “Justice to transcend conflict: Impact of Syrian conflict report” Syrian Center for Policy Research (2020): https://www.scpr-syria.org/justice-to-transcend-conflict/. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | COAR has explored Syria’s “gap economy” and the relevant entry points for locally driven development and donor-funded aid activities in detail in previous thematic papers. The stability of locally driven initiatives to fill service sector gaps is a key emphasis of COAR’s 2019 paper Beyond Checkpoints: Local Economic Gaps and the Political Economy of Syria’s Business Community. The prospects for local, grassroots development projects to meet community needs is the focus on the 2020 paper ‘Arrested Development’: Rethinking Local Development in Syria. |

| ↑3 | Notably, in his book Business Networks in Syria: The Political Economy of Authoritarian Resilience (2011), Bassam Haddad argues that since the 1970s, there was a growing alliance forming between business and security actors that gradually began dominating Syria’s economy. This alliance, which Haddad termed “fusion” between public and private spheres placed top state officials and extended family members at the highest levels of economy in Syria. |

| ↑4 | Joseph Daher, “The political economic context of Syria’s reconstruction: a prospective in light of a legacy of unequal development”. Middle East Directions (2019): |

| ↑5 | Two main outcomes were apparent. First, by instrumentalizing the state apparatus in this way, the regime channeled attractive positions to its allies and dependents. Second, privatization ensured that critical sectors such as telecommunications remained under de facto regime control. |

| ↑6 | The Central Bureau of Statistics does not clarify which workers are included in this number, although it likely excludes figures for the Ministry of Defense, whose data remains classified. |

| ↑7 | “2020 Budget Expenses – Full Details,” The Syria Report (2020): https://www.syria-report.com/library/budgets/2020-budget-expenses-full-details |

| ↑8 | Since 2011, there have been five official salary increases that were offered by the state to public sector workers and retirees: In 2011, 2013, 2015, 2016, and most recently in late 2019. |

| ↑9 | “The Living Costs for a Family of 5 in Damascus,” Kassioun (5 October 2020): https://kassioun.org/economic/item/65798-660-5-2020 (AR). |

| ↑10 | “Poverty,” World Bank Group (2020): https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/overview. |

| ↑11 | “Thousands of temporary workers waiting for decades for their contracts to be fixed,” Syrian Economic News (18 March 2019): https://sensyria.com/blog/archives/32043 (AR) and “The story of daily workers in Damascus’ bakeries,” Eqtsad (7 October 2017): https://www.eqtsad.net/news/article/18105/ (AR). |

| ↑12 | “Governor of Damascus resolves the issue of daily workers,” Al-Baath Media (2020): (AR). |

| ↑13 | “High cost of living pushed public sector workers to resign,” Bawaba Syria (2020): (AR). |

| ↑14 | However, the state has contemplated the privatization of national health insurance. |

| ↑15 | Efforts by the state to offset the public healthcare sector to private businesses and investors were not halted there. By the end of 2019, the Government of Syria considered establishing a private company to manage health insurance and regulate health expenses. Notably, according to a 2019 statement by the minister of finance, Maamoun Hamdan, the government pays around 264 billion SYP ($99.6 million) every year on health, including 150 billion SYP ($56.6 million) on hospitals and clinics and 114 billion SYP ($43 million) on medicines, and is having difficulties covering costs. This move was likely the state’s approach to a partial disinvestment from the health sector as it struggles to generate revenues and fill gaps created by economic contraction. |

| ↑16 | In 2014, public sector workers dominated the labor force and represented more than half of all employment. Similarly, data from the Central Bureau of Statistics show that even after 7 years of conflict, the public sector labor force remained at 44 percent in 2018. |

| ↑17 | This is also true of the militarized economy. Private military companies and foreign military powers have made inroads recruiting Syrians in part through attractive salaries, yet the scale of these market interventions is modest. |

| ↑18 | Tatjana Chahoud, “Syria’s Industrial Policy.” German Development Institute (2011): https://www.die-gdi.de/uploads/media/Syrienstudie.engl.arab.pdf |

| ↑19 | The General Organization for Sugar is a part of the Ministry of Industry, and it has factories and manufacturing companies for sugar and yeast in Homs, Al-Ghab, Tal Salhab, Maskanah, Al-Raqqa, Deir-ez-Zor, Damascus and Aleppo. Most of these have been offline for years. For more information see: “What is the link between the closure of Tal Salhab Sugar Beet Factory and Tarif Al-Akhras?” Al-Modon (4 August 2019): (AR) |

| ↑20 | “Moscow collects its spoils of war in Assad’s Syria,” Financial Times (1 September 2019): https://www.ft.com/content/30ddfdd0-b83e-11e9-96bd-8e884d3ea203 |

| ↑21 | For more information on Stroytransgaz’s investment in Syria’s post-conflict economy see: “Factsheet: Stroytransgaz in Syria,” The Syria Report (6 April 2020): |

| ↑22 | For more information on Iran’s investment in Syria’s post-conflict economy see: “Revolutionary Guards Get Hold of Syrian Mobile Phone Licence as Part of Broader Tehran Grab on Economic Assets,” The Syria Report (17 January 2017): . |

| ↑23 | For instance, in October 2020, Iran established a large commercial centre in the Damascus Free Trade Zone named ‘Iranian’ which is projected to facilitate trade between Syria and Iran and build a bridge between Syrian and Iranian chambers of commerce. For more information see:” Iran inaugurates the largest commercial center outside the borders in Damascus” Iranwire (19 October 2012): https://iranwirearabic.com/archives/9429 (AR). |

| ↑24 | “Regime Government Amends Private Sector Labour Law,” Tishreen (13 March 2019): https://bit.ly/2N326Ov. |

| ↑25 | It has been posited that a conceptual ultimatum confronts consumers in the face of deteriorating quality of goods: either exit or voice. To exit is to withdraw from the relationship (i.e. to emigrate). To voice is to attempt to repair the relationship by communication or complaint (i.e. protest). Syrians face a particular challenge in this paradigm, and few means of redress are available. For more information see: Hirschman, A.O. (1970). Exit, Voice and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations and States. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. |