Syria Update

21 December 2020

Need for seed: Damascus increasingly desperate for wheat

In Depth Analysis

Lacking realistic means of averting an impending wheat crisis, the Government of Syria has tightened agricultural support for wheat farmers as it scrambles to boost the imports that are needed to fill now-chronic production shortfalls. On 14 December, agricultural cooperatives in Dar’a reportedly forced farmers receiving subsidized wheat seed and fertilizer to sign a written pledge stating they would actively cultivate wheat, rather than divert the inputs to other uses, such as fertilizing other crops. While cooperatives have previously required farmers to obtain security clearances, this is to date the most restrictive covenant to ensure that subsidies which the state can ill-afford are actually used in strategic wheat production.

The problems

Syria’s wheat woes are the result of several interlocking crises. Foremost among them is the Syrian government’s loss of physical control over the country’s richest wheat-producing regions. Roughly 70 percent of the total wheat production comes from northeast Syria, which is under the auspices of the Self-Administration, which has outmaneuvered Damascus in the annual bidding wars over the all-important grain (see: Syria Update 8 June 2020).

A crumbling national economy and rock-bottom depreciation of the Syrian pound have also complicated efforts to procure wheat on the open market. In a recent announcement Syrian Grain Establishment Director of Foreign Trade Nazir Dubyan stated that six Russian companies have withdrawn from wheat contracts with Syria. The agreements would have provided 450,000 tons of wheat at $224 per ton. Dubyan claimed that the deals collapsed due to rising prices in global wheat markets, thus absolving either country of blame. This is specious reasoning that dodges uncomfortable questions about the Syrian state’s capacity to pay market prices. More importantly, the deals’ failure has focused pressure on the Syrian government, given that Russia has been Syria’s most reliable wheat supplier since grain security became a concern in the early years of the conflict.

Bereft of domestic harvests and incapable of sourcing through Russia or its cash-strapped ally Iran, the Syrian government has now turned to imports of unclear provenance. On 16 December, the Government of Syria reportedly contracted a Lebanese company, believed to be the grain specialist Freiha Holding, to supply 150,000 tons of wheat at $285 per ton — a reported discount of $25 per ton from other bids. Little is known about the firm or the deal at the time of writing, and there is currently no reason to suspect foul play. In the past, however, wheat import deals conducted through Lebanon have been tied to elite (usually sanctioned) Syrian businessmen, including Samer Foz. In all cases, transactions through the country are increasingly difficult. Lebanon’s financial crisis and the turmoil of the Beirut port explosion have challenged Syria’s access to regional and international markets and Syrian deposits in Lebanese banks. Figures vary, but the Economist Intelligence Unit recently estimated the total sum of Syrian deposits trapped in Lebanon could be as high as $40 billion, a considerable block on Syria’s liquidity and a major liability for the tottering Lebanese financial system.

The ‘solutions’

Wheat shortfalls ultimately become bread shortfalls. Rather than offering concrete, long-term solutions to the bread crisis in government-controlled areas, the Syrian state has transferred the costs of its failures onto the population. On 13 December, Minister of Local Trade Talal Barazi announced a series of harsh penalties targeting “bread traffickers,” an ill-defined group of supposed criminals that includes individuals whose product deviates from the official weight of a pack of bread (1.1 kg). Offenders risk five years in detention with hard labor. Barazi further attributed the bread crisis to “grave offenses against bread products” that have supposedly increased by 420 percent since last year. Barazi’s announcement comes shortly after Minister of Agriculture Mohammad Hassan Qatana stated, on 6 December, that Syrians must rely on themselves to secure bread and should not wait for government assistance. Instead, he advised helping the state by baking bread at home. This is a further downward slide since the introduction of rules intended to reduce household consumption by rationing bread purchases at state-subsidized bakeries (see: Syria Update 21 September 2020).

The reality

In its inept attempts to fix the wheat crisis, the Government of Syria risks causing further damage elsewhere. In designating the impending crop season the “Year of Wheat,” the state hopes to plant 1.8 million hectares of the grain (see: Syria Update 30 November 2020). This target invites unintended impacts as wheat fields spring up where soil quality and market forces have driven farmers to cultivate other crops in the past. All things considered, wheat planting likely will expand, and in so doing, it will displace other non-wheat crops, with potentially devastating effects. One key impact will be on fruit and vegetable cultivation, which has traditionally been a major source of foreign revenue via exports to Jordan and the Gulf, particularly for agriculturalists in southern Syria. In effect, producers are likely to suffer reduced export revenues on fruits and vegetables so the state can trim its own expenses on wheat imports. The crop calculus may benefit the state, but farmers will lose, and networked industries such as transportation will also suffer. By employing temporary solutions to resolve a deeply entrenched crisis, the Government of Syria may change the nature of the food and livelihoods crises, but it is unlikely to succeed in resolving them.

Whole of Syria Review

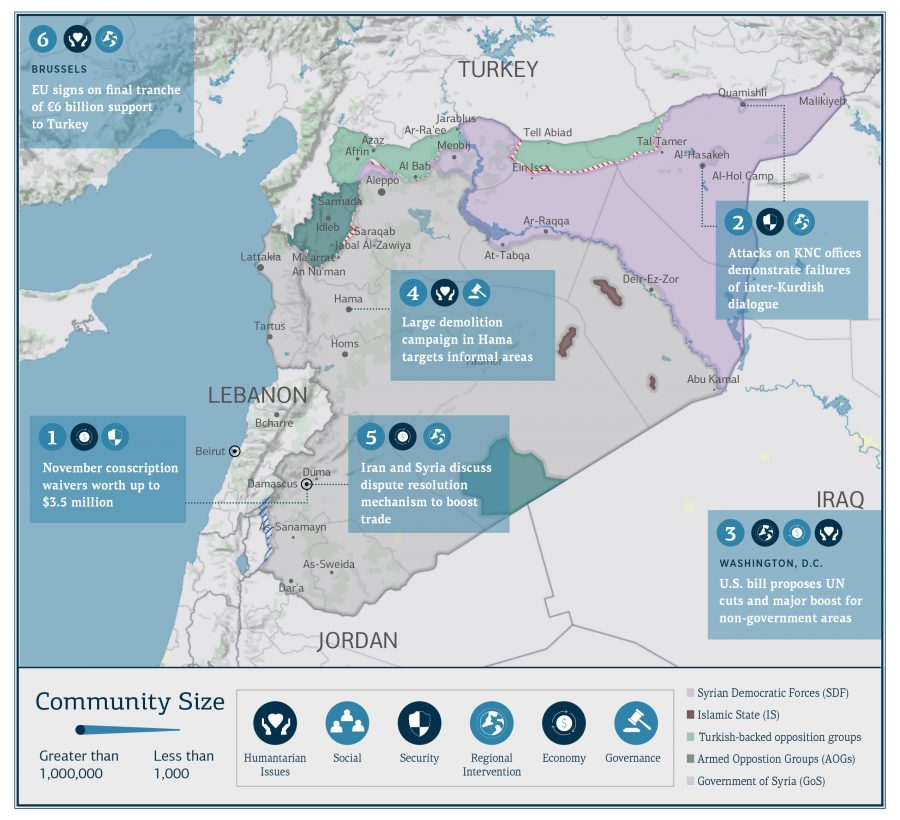

1. November conscription waivers worth up to $3.5 million

Damascus: In early December, the Syrian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) published lists with the names of the Syrians abroad who have been vetted and cleared to avoid military conscription by paying a waiver. The lists are categorized by month, and they date back to May 2020. The November lists alone comprise approximately 450 names across all governorates. The majority of those approved (196) hail originally from Damascus and Rural Damascus. Only five waivers were approved for those from Al-Hasakeh governorate. Waiver-seekers will have to pay $7,000 or $8,000, depending upon how long they have resided outside the country. It is not immediately clear how the figures reflect waivers for Syrians inside the country through a policy introduced by Finance Minister Kinan Yaghi on 3 November (see: Syria Update 9 November 2020). It will reportedly cost $3,000, to be paid at a purpose-formed exchange rate established by the Central Bank of Syria (see: Syria Update 7 December 2020).

From policy to practice

While it is unclear how many people will actually pay the waiver, there is no doubt that the policy aims to increase government revenues. If all those approved in November avail themselves of the system, Damascus will net as much as $3.5 million. The waiver is the Government of Syria’s latest innovation in unconventional revenue collection through heavy fees for administrative and bureaucratic services. In 2020, for instance, government revenues from passport issuance reached $22 million, with each passport costing between $300 (normal track) and $800 (fast-track). All told, the Syrian state transforming from an apparatus that ensures equal access to entitlements, services, and benefits to a system that perpetuates its own rule through revenue extraction from its own captive population.

2. Attacks on KNC offices demonstrate failures of inter-Kurdish dialogue

Quamishli, Al-Hasakeh: A pitched increase in violent protest and inter-party friction among Iraqi Kurdish parties that ignited in early December has now spilled over to northeast Syria. On 16 December, local media reported that unidentified gunmen, believed to be Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) affiliates, attacked the offices of rival local Kurdish political parties in Al-Hasakeh, Quamishli, Amuda, Darbasiyah, and Ain Al Arab (Kobane) cities. In response to the attacks, the Kurdish National Council (KNC) claimed the attacks undermine inter-Kurdish dialogue. The Syrian Opposition, of which the KNC is a part, also condemned the attacks. Relatedly, on 15 December, YPG combatants reportedly clashed with Iraqi Peshmerga forces using medium and heavy weapons at the Fish Khabour border crossing with Iraq, following a failed smuggling operation. SDF commander Mazloum Abdi condemned the attack. Adbi stressed that this only hurts the Kurdish cause and that their disputes should be resolved through dialogue.

Ankara: The elephant in the room

The flare-ups punctuate a long series of spats between Kurdish political parties and their armed affiliates. The attacks were seemingly targeted, and they do not herald the outbreak of violence on a wider scale in northeast Syria. However, any reprisals that do target perceived PKK elements, or the SDF itself, risk collateral damage to the Self-Administration entities that are the primary gatekeepers for humanitarian access to northeast Syria.

More broadly, the incidents demonstrate that genuine Kurdish rapprochement is likely to remain out of reach for the foreseeable future, despite the prodding of the U.S.-led coalition. The attacks on KNC offices in Syria highlight the credibility gap between the Self-Administration’s vows to create a big tent political outfit and its inability or unwillingness to put this pledge into practice. Abdi’s condemnation of the violence is not a surprise. The SDF commander has clearly (and accurately) articulated that the Self-Administration will continue to need the deterrence furnished by the bayonet, but its future will be secured at the ballot box and through dialogue (see: Syria Update 7 December 2020). Actually doing so will prove more challenging.

Notionally, sustained positive relations between the Self-Administration (dominated by the Syrian affiliate of the PKK) and the KNC, arguably the most important Syrian party linked to the Barzani government in Iraqi Kurdistan, would create a rising tide that lifts all boats. In Syria, however, such calculations have seldom translated into action. Nor are they likely to in this case, not least because Turkey looms large over the area. Barzani’s clientist relationship with Ankara has always complicated peer-level relations with the Self-Administration, which Turkey views as an unambiguous threat. Increasingly throughout 2020, Turkey has carried out military attacks on PKK sites in Iraq, including from bases it has established in Iraq’s northern frontiers. The international community will almost certainly continue to push for Kurdish reconciliation, but structural impediments will admit no easy solutions until the very identity of either entity changes. Future clashes within the Self-Administration are a virtual certainty, as are run-ins across the Syria-Iraq border.

3. U.S. bill proposes UN cuts and major boost for non-government areas

Washington, D.C.: On 10 December, U.S. Representative Joe Wilson introduced a grandstanding bill to “to explicitly support the Syrian people’s movement to remove the Assad regime.” The Stop the Killing in Syria Act 2020 draft legislation proposes myriad financial and military tools to galvanize domestic opposition to Bashar Al-Assad and prevent the regional normalization of relations with Damascus. Financially, it calls for:

- The sanctioning of the Syrian financial sector “in its entirety”;

- A determination where “areas of Syria” under Government of Syria, Russian, or Iranian control are a primary money laundering concern;

- A formal review to determine whether “officials and businesses” of nations that have diplomatic or economic relations with the Syrian government are in violation of the Caesar sanctions (see: Syria Update 22 June 2020);

- The creation of Free Syria Economic Zones in areas outside the control of the Syrian government and “terrorist group[s],” which will enjoy sanctions waivers and duty-free trade;

- The suspension of U.S. aid for UN programs in government-held areas, “unless a certification can be met that such assistance is not supporting the Assad regime, Russia, or Iran.”

The bill is no less ambitious militarily and diplomatically. It also calls for:

- The U.S. president to “develop a comprehensive strategy” to remove Al-Assad from power and expel Russian and Syrian forces from the country;

- A study into the feasibility of enforcing a no-fly zone.

An unstoppable force meets an immovable object

The bill carries forward recommendations originally made by the socially conservative Republican Study Committee, and the conditions needed for its passage are difficult to envisage in the current U.S. political climate. Nonetheless, there are ways for even an unpopular or marginal bill to become law. The Caesar Act languished on Congressional sidelines after it was originally introduced in 2016. After multiple false starts, it became law as a rider to the “must-pass” defense spending bill in December 2019. Like the headline sanctions they seek to leverage, the proposed legislation would have an enormous impact for the international Syria response.

The pressure and partition scheme contained in the bill are a tacit recognition that the Syrian stalemate is unlikely to be broken any time soon. All told, the bill would isolate, impoverish, and degrade Syrian government areas while stabilizing and empowering the opposition-held northwest. Read against current U.S. compliance concerns, the text suggests that Salvation Government-administered areas would be beyond the pale and, therefore, incapable of enjoying free trade and sanction waivers. Presumably, the Self-Administration would also benefit, although deeper penetration by Russian forces and the Syrian government leaves room for doubt.

The bill also has regional and international aspects. Like the Caesar sanctions, it seeks to deter Gulf investors, in particular, from profiting off rapprochement with Damascus. The expulsion of Russian and Iranian forces from Syria should be seen as an ideological preference but an improbable policy. Moveover, the bill’s vow to sanction “Lebanese security forces involved in supporting the Assad regime or involved in the forced repatriation of Syrian refugees” evinces a willingness to destabilize neighboring Lebanon in order to spite Tehran and Damascus. That Chinese firms — which have eschewed the Syrian market as unstable and politically unpredictable — are also in the bill’s crosshairs will give some indication of its ideological bearing.

4. Large demolition campaign in Hama targets informal areas

Hama city, Hama governorate: Large-scale building demolitions continue in neighborhoods across Hama city as the activist governor, Mohammad Krishani, has personally pushed for bulldozing crews “to do their work.” Demolitions began on 30 November in informal areas in the Al-Naqarneh neighborhood and have since expanded to Kazou, Wadi Al-Joz, and Mazraa Al-Dhahiyeh neighborhoods. Krishani ordered the demolition of houses, warehouses, and three factories. The rubble from the buildings was subsequently seized, while industrial equipment and generators were placed under judicial custody. Krishani has zealously spurred on the Central Demolitions Committee, justifying the razing of Al-Naqarneh by claiming that the affected structures “belong to traders who deal in buildings that are in violation of code on a large scale and do not belong to impoverished residents.”

A wrecking ball policy

Hama has witnessed mass demolitions before. As with past waves of reclamation, the current campaign targets informal neighborhoods, where it risks dispossessing marginalized populations on a large scale. Despite the assurances made by Krishani, large portions of the affected areas are residential, and the massive displacement that has accompanied current and past demolitions belies the claim that only illegally operating businesses are affected. Hama city sustained light to moderate conflict damage, yet demolition campaigns targeting informal neighborhoods have displaced thousands of residents without offering alternative housing or compensation. Wadi Al-Joz was one of the largest informal neighborhoods in Hama. In September 2013, following the withdrawal of opposition forces, demolition in the neighborhood displaced 25,000 people. Of note, the Central Demolitions Committee that carries out demolitions predates the conflict, and is formed under Decree No. 59 of 2008. Yet the conflict has seemingly set it working in overdrive.

5. Iran and Syria discuss dispute resolution mechanism to boost trade

Damascus: On 14 December, local media reported that Iran and Syria are exploring the creation of a dispute resolution mechanism among other steps to resolve what they describe as routine technical barriers to increased bilateral trade. The suggested system was discussed during a digital meeting between the head of the Syrian Union of Chambers of Trade, Muhammad Abu Hadi Lahham, and the Iranian envoy to Syria. The dispute resolution mechanism is meant to avert the need for formal legal arbitration, should actionable disagreements arise.

A better business bureau

Direct business-to-business relationships are the backbone of Iran’s efforts to convert military prowess and local prestige into meaningful leverage on the ground in Syria. For the time being, “maximum pressure” and collapsing state finances have sunk Tehran’s hopes of state-led investment or of gaining real purchase over Syrian industries at scale. Private sector cooperation represents a fallback position, but returns to date have been modest. Knocking down trade barriers may help some, but thorny compliance requirements and limited access to important financial instruments are likely far greater barriers to trade than are concerns over legal disputes among traders. The recent creation of a direct barter system for food oils is evidence of just how daunting the real fiscal challenges are. Trade growth is likely, but only because the starting point is so low.

6. EU signs on final tranche of €6 billion support to Turkey

Brussels: On 17 December, the European Union signed an agreement pledging the final €780 million tranche of aid for Syrian refugees in Turkey, completing its 2016 pledge of €6 billion ($7.3 billion). The latest funding covers health care, protection, basic needs, infrastructure, and economic support to Syrians and local host communities.

Out of the frying pan, into the fire

International donor support to Turkey has been critical to preventing mass refugee exodus and stabilizing host communities. However, regional tensions are as high as at any point in recent memory, and domestic political pressures inside Turkey are mounting, creating a very real possibility that anti-refugee sentiment will once again become a dominant feature of the Turkish political landscape. In particular, the slowdown brought on by COVID-19 and a nationwide economic bust has already primed the pump for domestic resentment of outsiders in Turkey. The possibility of further international sanctions and restrictive measures will only add kindling to the fire. Upcoming elections will fan the flames more yet. Of course, the pressures on refugees themselves have compounded too. It is estimated that 1.1 million Syrian refugees in Jordan, Lebanon, and Iraqi Kurdistan have been driven into poverty since the onset of the COVID-19 crisis. Figures for Turkey would likely show a similar slide. That said, large-scale, voluntary refugee returns have yet to take place, given that conditions inside Syria are worse yet. If legal and financial pressures in host countries increase, however, this reality may change.

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below.

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

Syrian opinion split on decentralizing power in new constitution

What Does it Say? A new public opinion survey shows an uptick in favorability toward administrative decentralization.

Reading Between the Lines: Support for decentralization is, predictably, strongest among Kurds, but support has also grown considerably among other minority groups, including Christians and, notably, Alawites. This is especially important in light of recent moves by Al-Assad to re-invent Syria as Sunni Arab nation.

Source: Middle East Institute

Language: English

Date: 10 December 2020

Number of out of school children doubles in northern Syria as coronavirus, poverty take their toll

What Does it Say? Save the Children has reported that nearly half the students in northern Syria in school before the COVID-19 outbreak have since dropped out.

Reading Between the Lines: Ten years of conflict and the COVID-19 pandemic have utterly decimated many families’ finances, leaving them incapable of sending their children to school. While tech-based and other solutions have been proposed, fundamental barriers remain unaddressed. The ultimate consequence may be a much-dreaded “lost generation.”

Source: Save the Children

Language: English

Date: 10 December 2020

What Does it Say? The article relates the experiences of the many Syrian fighters who participated in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict as mercenaries fighting for both sides.

Reading Between the Lines: Many men in Syria have been battle-hardened over the past decade, and many have few livelihoods skills apart from war-fighting. With dwindling opportunities in Syria, more men are likely to look abroad in search of conflicts to ply their trade.

Source: Enab Baladi

Language: Arabic

Date: 14 December 2020

America’s War on Syrian Civilians

What Does it Say? The article explores the U.S.-led campaign against ISIS in Ar-Raqqa city, raising questions about the legality and morality of the use of drones, particularly in populated areas.

Reading Between the Lines: Drone warfare has posed thorny legal and moral questions since its advent. It is especially notable that the campaign to liberate Ar-Raqqa is often held up as a counterpoint to Russia’s use of air power in populated areas such as Aleppo. Despite the differences in U.S. and Russian rhetoric and state intentions, from the ground level, Syrians must strain to see a meaningful distinction between outcomes.

Source: The New Yorker

Language: English

Date: 21 December 2020

Lost Telecommunications Amidst Belligerent Groups in Northeast Syria

What Does it Say? The article details the status of telecommunications networks and access in northeast Syria.

Reading Between the Lines: With three competing powers vying over network control — the Syrian government, Turkey, and the Self-Administration — service provision has been splintered, and myriad knockon effects have become apparent.

Source: SMEX

Language: English

Date: 14 December 2020

How Russia is preparing in Syria for Biden’s presidency

What Does it Say? Russia is attempting to reinforce its positions before Trump’s term as president ends.

Reading Between the Lines: In addition to beefing up its presence in northeast Syria, Moscow is seeking to benefit from a favorable balance among regional players whose interests run counter to likely Biden administration priorities.

Source: Al-Monitor

Language: English

Date: 14 December 2020

A woman runs the most dangerous camp in Syria and aspires to peace

What Does it Say? The story notes that some wives of ISIS fighters, now in Al-Hol camp, are refusing aid from the camp administrators because they consider them to be infidels.

Reading Between the Lines: While much has been written about the potential security and radicalization challenges present in the camp, it is also important to note that implementation is itself a challenge. Successfully programming in the camp may require a more granular understanding of its population demographics.

Source: Syria Untold

Language: Arabic

Date: 4 December 2020

On the Return of Syrian Refugees

What Does it Say? The report introduces a three-part initiative to document the scale and challenges for Syrian refugee in the region.

Reading Between the Lines: Refugee return remains a foremost concern for the international community. Although there are credible fears that deteriorating conditions in host nations will spark returns, voluntary returns to Syria have, according to TIMEP, dwindled to 21,618 in 2020, down from 94,971 in 2019. This decrease is likely due to the movement restrictions induced by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Source: The Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy

Language: English

Date: 14 December 2020

What Does it Say? Many former government employees in Dar’a have been waiting almost two years to get their jobs back, with no clear indication of when or whether it will happen at all.

Reading Between the Lines: Myriad challenges face former administrators, civil servants, and aid workers in reconciled areas. This is a daunting prospect for communities themselves, but it is an especially relevant challenge for the international aid community, which may lose entry points for programming if skilled technocrats are displaced.

Source: Daraa 24

Language: Arabic

Date: 15 December 2020

The Wartime and Post-Conflict Syria project (WPCS) is funded by the European Union and implemented through a partnership between the European University Institute (Middle East Directions Programme) and the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR). WPCS will provide operational and strategic analysis to policymakers and programmers concerning prospects, challenges, trends, and policy options with respect to a conflict and post-conflict Syria. WPCS also aims to stimulate new approaches and policy responses to the Syrian conflict through a regular dialogue between researchers, policymakers and donors, and implementers, as well as to build a new network of Syrian researchers that will contribute to research informing international policy and practice related to their country.