Syria Update

4 January 2021

Sanctions on Syria’s Central Bank Set Course for a Grim 2021

In Depth Analysis

On 22 December, the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctioned the Central Bank of Syria in a year-end salvo. The latest round of sanctions specifically “aims to discourage future investment in government-controlled areas of Syria, force the regime to end its atrocities against the Syrian people, and compel its commitment to the United Nations–facilitated process in line with UN Security Council Resolution 2254.” Also sanctioned were Lina al-Kinayeh, an official advising the Syrian Presidency on anti-corruption measures, and her husband, MP Mohammad Masouti. OFAC charges that they and several affiliated businesses have served as financial proxies for the Syrian regime, First Lady Asma al-Assad in particular.

The sanctioning of the central bank is the swan song of a year in which Syria witnessed extreme economic volatility and a deepening fiscal crisis. As of 1 January 2021, the Syrian pound traded at roughly 2,830 SYP/USD, having lost two-thirds of its value over the course of 2020 — the currency’s worst year ever. Syria’s central bank enters 2021 with a diminished toolkit, while the sanctions that have piled up over the conflict will make it harder for Damascus to halt currency collapse or remediate downstream impacts such as inflation and the popular misery brought on by goods shortages. In the year ahead, Damascus will continue to push the costs of these failures onto the Syrian population, leaving the international aid response to confront a bracing question for 2021: How can principled aid implementers meet growing humanitarian and non-humanitarian needs in an increasingly complex operational environment?

Economic blight

Until a definitive end to the conflict is achieved, there is no realistic hope of stabilizing the Syrian pound or repairing the cratered national economy. Syria’s immiseration is not a result of sanctions on the central bank or other institutions and actors; rather, it is a product of a decade spent at war. Yet, by openly blocking the organic return of economic activity, sanctions move the starting line for recovery further beyond reach (see: Syria Update 22 June 2020). For that reason, a UN special rapporteur has since called for the Caesar sanctions to be lifted. Although Syria’s central bank governor, Hazem Qarfoul, was already under sanction, the latest sanctions place all financial transactions in government-held areas, or involving Syrian state entities and government institutions, under a microscope (see: Syria Update 5 October 2020).

Syria’s bleak economic outlook has real-world consequences. Most notably, economic malaise is driving growing food insecurity. This is in part due to challenges on the production side, particularly for wheat (see: Syria Update 21 December 2020). FAO reports that the Syrian government is able to satisfy only 20 percent of the national demand for strategically important grain seed. As a result, farmers must resort to the private market for seed and other inputs, including fuel and fertilizer — sometimes paying double the government rate. Fiscal shortfalls prevent the Syrian government from enacting commonsense workarounds. This is most apparent in the state’s inability to secure wheat imports. This failure has led to stricter bread rationing, dietary substitutions, and humiliating bread lines. A year-end one-time survival check from Damascus — 50,000 SYP for current enlistees and civil servants and 40,000 SYP for pensioners — is worth less than $20. For struggling Syrians, it is too little, too late.

Aid inaction

Sanctioning the Central Bank of Syria will increase compliance and due diligence requirements and raise additional barriers, in an already challenging aid environment. Actors seeking to implement in areas held by the Government of Syria will now likely be forced to clear further hurdles to transfer or convert money or pay the salaries of local staff.

Implicitly, the measure pressures the international community to divert funding to areas outside the Syrian government’s reach, particularly northeast Syria, where compliance barriers are comparatively modest. The U.S. has long advocated for the donor community to give more support to the Self-Administration. Sanctioning the Central Bank of Syria furthers Washington’s overarching ambition to strengthen outlying areas of Syria, thereby weakening Damascus in the long term.

Blowback

However, the risk of unintended outcomes remains. Operating from an incomplete understanding of the context increases this risk.

For one, the close inner circle of President Bashar al-Assad profits from its ties with an international business network created to evade sanctions. These actors have flourished as more and more of the Syrian economy is converted to informal activity. For instance, in 2011, only 1 percent of Syrian imports had no listed country of origin. By 2018, that figure reached 40 percent, suggesting a windfall for middlemen and business insiders whose sole utility is sanctions-avoidance. While it is true that sanctions targeting state institutions erode governance and service capacity, they do not hobble the Assad regime directly.

At the same time, legitimate economic opportunities are also diminishing. Syrians are becoming reliant on illicit economies, mercenary service, bribery, and war-economy activities in ever-greater numbers (see: The Syrian Economy at War: Armed Group Mobilization as Livelihood and Protection Strategy and The Syrian Economy at War Labor Pains Amid the Blurring of the Public and Private Sectors). In many instances, these illicit activities are mediated through the rump state, via the civil service, checkpoints, or public-private enterprises. In the long term, international priorities such as the restoration of the rule of law and the reinstitution of good governance will be a threat to livelihoods that now depend on state atrophy. The Syrian state is failing, and the Assad regime and growing numbers of ordinary Syrians are profiting from that failure, while the majority suffers.

Moreover, the longitudinal impact of sanctions is frequently overlooked. While there is some hope that enterprise can provide jobs and goods, overall, sanctions hamper business. For instance, industrial maintenance and the replacement of machinery and software cannot be delayed in perpetuity. Syria has been under severe sanction for nearly a decade. In many cases, enterprises are forced to make due with equipment and software that date to the pre-Arab Spring era, or find expensive and dubious workarounds. Those that are still functioning will find it harder to keep the lights on as Syria’s pariah status continues. Under these conditions, the Syrian government’s losses have been Tehran and Moscow’s gains. Syria’s economic concessions to Russia and Iran will scale with its wartime debts to these critical international allies, who see Western sanction as an opportunity. On 26 December, Iran’s bilateral trade commission with Syria reportedly announced that the nations are close to launching an “internal SWIFT” system to evade sanctions and facilitate direct trade. The formation and impact of the system should be viewed skeptically, given the graveyard of failed trade agreements between Damascus and Tehran. However, there is no doubt that a small ring of business elites in both nations is eager to seek profit through private-sector relations that are now a lynchin of Iranian-Syrian cooperation (see: Syria Update 21 December 2020).

Global leadership will undergo a step-change as 2020 gives way to a new year (see: Syria Update 16 November 2020). Yet, there is little reason to suspect that a major about-face on Syria is in the offing. It is therefore imperative that the donor-funded Syria response continue planning for a sobering reality: that international Syria policy stays the course.

Whole of Syria Review

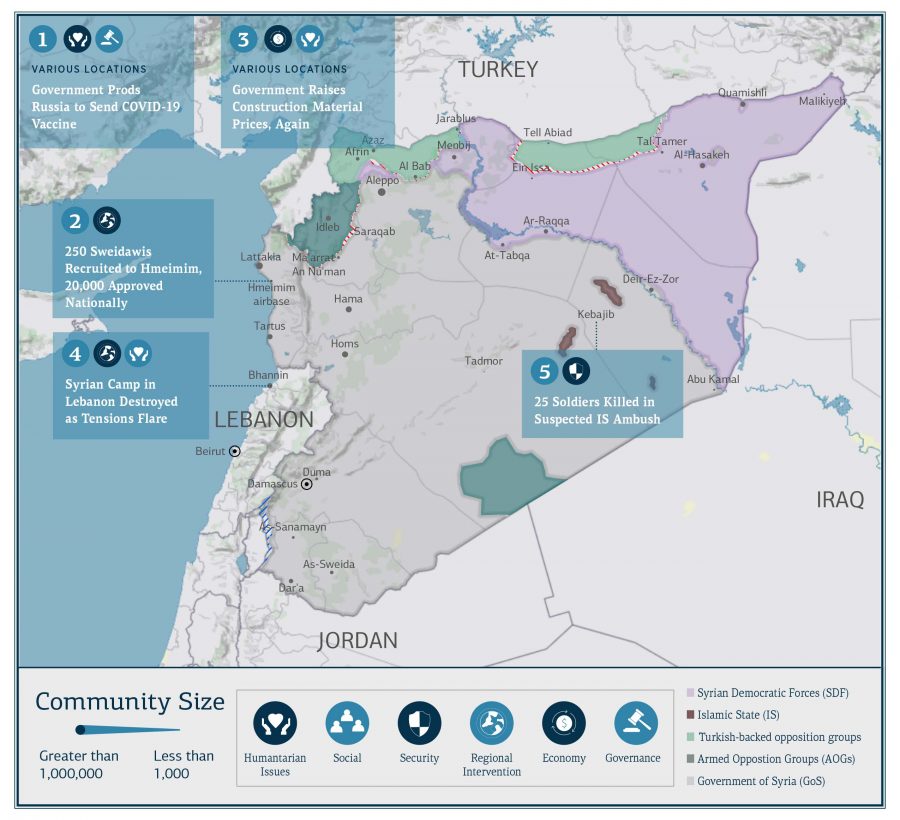

1.Government Prods Russia to Send COVID-19 Vaccine

Various locations: Negotiations remain underway between the Syrian and Russia governments for the distribution of the Russian-manufactured COVID-19 vaccine, Sputnik V, in Syria. On 21 December, Syria’s foreign minister, Faisal Mekdad, told Russian media that the Syrian public hopes to acquire Sputnik V because “[they] trust Russian vaccines more than Pfizer and others.” When asked whether Russia would donate the vaccine, Mekdad said he was “confident that the Russian people are generous enough to take such aspects into consideration, especially given the economic and physical damage wrought on the country throughout the conflict.” On 22 December, the director of the emergency department at the Syrian Ministry of Health, Tawfiq Hassaba, announced that the Government of Syria would receive the COVID-19 vaccine commissioned by the World Health Organization (WHO) in the first quarter of 2021. At the time of writing, neither the WHO nor the Russian government has commented on the statements.

Long waiting list

Syria faces myriad challenges in its attempts to procure a COVID-19 vaccine, and the country continues to hurtle toward uncontrolled community spread (see: Syria Update 16 November 2020). Given wealthy countries’ priority access to Western-produced vaccines, Syria continues to cast about for alternatives, including Russian and Chinese jabs that have been produced with less transparency. Little trial data concerning the Russian-manufactured Sputnik V has come to light since the initial announcement of phase-three trial results was made in November. Similarly, questions concerning the efficacy of the Chinese-manufactured vaccine are yet to be answered. That said, Syria is among the many countries for which Sino-Russian solutions — or global largesse, for instance, through the WHO — may be the only realistic medium-term options.

At present, more than 150 countries have ordered Sputnik V. Syria is unlikely to be near the top of the list for delivery. Nationwide economic destitution means that scant resources are available for procurement. Mekdad’s remarks concerning the donation of Sputnik V are unlikely to prompt large-scale handouts from a tight-fisted Kremlin. Although Russia has reportedly weighed in against a resumption of major fighting in northwest Syria due to its concerns over COVID-19, it is not a given that Russia will push out the vaccine in Syria simply as a means of recapturing Idleb. Token donations on a small scale are more likely. Syrian government and military figures are likely to be prioritized if or when a vaccine does arrive. It is also possible that Syria will be forced to make further economic concessions to Moscow in return for the vaccine.

Syria’s penury is one thing. The lack of concentrated government efforts to combat the virus’s spread is another altogether. Since lifting lockdown conditions in spring, the Syrian government has countenanced seemingly uncontrolled spread for want of realistic options to combat the virus. The number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in government-controlled areas has reached 10,442 as of writing, according to the Syrian Ministry of Health. Independent estimates put the number at more than 100,000, although accurate figures are impossible to pin down, given data gaps and limited testing. Nonetheless, the Government of Syria has eased anti-COVID measures, including by reopening the Aleppo International Airport, after its shutdown in March. Rehabilitation work on Bassel Al-Assad International Airport, in Lattakia, has also reportedly resumed. The Syrian Ministry of Education has emphasized the need to continue educating students, as an argument against shuttering schools. All this suggests that wishful thinking will remain the Syrian government’s primary defense against COVID-19 infection until a vaccine arrives.

2. 250 Sweidawis Recruited to Hmeimim, 20,000 Approved Nationally

Hmeimim airbase: As of late December, local media report that Syrian Military Security has approved the requests of approximately 20,000 Syrians who applied for recruitment via private military companies. The approvals pave the way for Syrian recruits to be fed into local private military companies, in a Russian-sponsored scheme. It is presumed that selected recruits will be seconded to Russia through the Wagner Group, where they are expected to be deployed to Libya, or elsewhere. Reportedly, 250 fighters from Sweida governorate deployed to Hmeimim airbase on 22 December as a first step in this process.

Syria’s one booming industry: war

Foreign military recruitment in Syria has exploded in the year since the first confirmed reports that Syrian fighters would be deployed to Libya (see: Syria Update 6 January 2020). The pace and scale of recruitment are likely to grow in 2021, creating a direct pipeline to export violence beyond Syria’s borders, threatening stability throughout the wider region. The mercenary recruitment of Syrians is especially problematic because it is driven in large part by an increasing dearth of civilian-sector opportunities (see: The Syrian economy at war: Armed group mobilization as livelihood and protection strategy). That said, although 20,000 fighters have been provisionally approved to fight in private armies, the actual pace of recruitment will likely hinge on Moscow’s manpower needs. In parallel, untold numbers of fighters are likely pursuing recruitment through Turkish-backed groups in northern Syria, including to fight Russian-sponsored Syrian mercenaries abroad. Although military recruitment is among the few attractive livelihoods in Syria, those fighting abroad have learned the same lessons as private contractors elsewhere: the fighting can be tough, and pay days are do not always meet expectations. Reports of arrears among Syrians fighting in Libya is the latest evidence of this. Finally, it is important to note the role played by Syrian middlemen and private military companies. Private armies — a necessity prompted by the fragmentation of Syria’s military command structure — was a wartime necessity. How and whether these formations will be used inside Syria in a post-conflict context remains to be seen. However, Damascus has seldom tolerated independent power structures. Frictions can be expected if or when these formations are reintegrated into the state.

3. Government Raises Construction Material Prices, Again

Various locations: On 19 December, the Syrian Ministry of Domestic Trade and Consumer Protection issued a decision raising the price of cement by approximately 80 percent. This is the second increase issued since August 2020, when the prices of various types of cement jumped by 50 percent (see: Syria Update 14 September 2020). According to the latest decision, the Government price for one ton of packed cement increased from 70,000 SYP (approx. $24) to 125,000 SYP (approx. $43), while bulk prices increased from 61,000 SYP (approx. $21) to 106,000 SYP (approx. $36). The ministry attributed the price hike to high production costs.

According to media sources, in some governorates, cement reportedly trades between 200,000 and 250,000 SYP (approx. $70-86) per ton on the black market. Relatedly, the price of steel also increased by 25 percent, from 1.5 million SYP per ton (approx. $520) to 2.1 million SYP per ton (approx. $725).

Concrete losses

The price of basic construction materials in Syria continues to rise to keep pace with unchecked inflation. The costs of this realignment will be borne by already struggling Syrians and conflict-affected communities. Real estate prices and the costs associated with local rehabilitation activities will rise accordingly. Humanitarian and non-humanitarian activities will also feel the squeeze. Donor-funded projects that require cement and metal construction materials, such as WASH, rehabilitation, and shelter activities may be affected. Notably, the inflation of these construction materials in 2020 outpaced the upward adjustments to official conversion rates set by the Central Bank of Syria. As a result, implementers and program designers must remain flexible when budgeting long-range procurement options. Meanwhile, the fact that black market prices have grown at a steady pace alongside official prices suggests that market supply remains somewhat stable, despite the significant shocks to the Syrian — and regional — economic systems. Although cement has continued to flow into the Syrian market via imports from Turkey and smuggling via Lebanon, other industrial imports are tightly restricted (see: Syria Update 14 September 2020).

4. Syrian Camp in Lebanon Destroyed as Tensions Flare

Bhannin, Lebanon: On 26 December, more than 370 Syrian refugees sheltering in an informal camp in northern Lebanon’s Bhannin were displaced after tensions with the host community developed into an armed confrontation and fire destroyed the camp. Shelters in the camp were deliberately set alight, according to the Lebanese Armed Forces, after a labor dispute between a local Lebanese family and Syrians living in the camp escalated to gunfire. No casualties were reported as a result of the confrontation, although four people were taken to hospital with minor injuries following the blaze, according to Khaled Kabbara, a UNHCR spokesman in northern Lebanon. Two Lebanese and six Syrians have reportedly been arrested over the incident. In a televised interview, North Lebanon Governor Ramzi Nohra strongly condemned the incident, noting that the camp is under the aegis of the Lebanese Armed Forces and UN organizations.

Getting real on returns in 2021

The Bhannin incident is emblematic of the tensions that persist in Lebanon between Syrians — refugees and foreign workers alike — and host communities (see: Syria Update 30 November 2020). In this case, community leaders in Akkar intervened to de-escalate tensions, and many offered affected refugees alternative shelter. The governorate of Akkar has historically been neglected by the Lebanese central government, leading to inadequate infrastructure and services and high rates of poverty. Hezbollah denounced the fire and called for a punitive response to deter future clashes. Meanwhile, the Syrian Foreign Ministry seized on the event as an opportunity to call for refugee return, stating, “The Syrian government is doing its best to facilitate their return and provide them with the requirements for a decent living in their cities and villages according to the available capabilities.”

Without question, the return of Syrian refugees will be an issue of foremost concern in 2021. The stark reality of Lebanon’s economic deterioration makes this question all the more pressing. Lebanon’s central government is struggling to extend subsidies on vital staples and medicines. Meanwhile, 89 percent of Syrian refugees in Lebanon cannot afford the survival minimum expenditure basket, according to the latest Regional Refugee & Resilience Plan, up from 55 percent one year ago. The litany of challenges facing Syrian refugees in Lebanon and elsewhere in the region will only grow more formidable over time. Yet the most decisive factor for Syrians abroad will likely be the conditions inside Syria itself. So long as ground realities in Syria remain uninviting and refugees abroad have the means of avoiding return, they are likely to do so, whatever the cost. Response actors should plan accordingly.

5. 25 Soldiers Killed in Suspected IS Ambush

Kebajib, Deir-ez-Zor governorate: On 30 December, at least 25 soldiers were killed and 13 were injured in a suspected Islamic State (IS) attack on a Government of Syria convoy near Kebajib, approximately 50 km southwest of Deir-ez-Zor city, according to Syrian state media. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights later reported that the soldiers belonged to the Fourth Division. The UK-based monitoring group claimed that 37 combatants had been killed and 10 injured in the ambush. Russian media, however, reported that at least eight civilians were among those killed. In the incident’s immediate aftermath, Russian aircraft reportedly carried out at least 60 airstrikes in rural Deir-ez-Zor, targeting areas in the vicinity of the attack.

Whack-a-mole

The attack confirms that dislocated IS cells have not been entirely eliminated from the Syrian Badiya, or eastern hinterlands, and it emphasizes that the organization remains capable of carrying out significant attacks. The assault stands out as the most ambitious military undertaking to have been carried out in Syria during the holiday period. This season can therefore be seen as a notable departure from previous years of fighting, which have been characterized by major end-of-year military operations. COVID-19 and frozen frontlines have locked Syria into a particular territorial configuration for the longest period since the conflict began, but the attack is a reminder that IS cells have immediate objectives that do not hinge on grand strategy. Looking ahead, future attacks can be expected, and efforts to degrade IS’s institutional capacity, which is fragmented and dispersed, will run up against hard truths. The Syrian desert is expansive, the nation’s borders are porous, and IS is a low priority for actors on the ground. Moreover, any efforts to squeeze the group in the immediate area may be stymied by the fact that so long as IS attacks are directed at Syrian government forces, local populations in much of eastern Syria will have little reason to object.

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below.

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

As Discontent Grows in Syria, Assad Struggles to Retain Support of Alawites

What does it say? The article assesses future scenarios built on the Assad regime’s struggles to preserve the support of Alawites, an inalienable constituency.

Reading between the lines: It is true that the Assad government’s popularity has flagged in recent years as hardship has grown, including for Alawites, who have borne major social and political costs due to their perceived affiliation with the regime. Writ large, however, the community has little means of ‘voting with its feet’ and throwing its support elsewhere. Yes, vertical pressures are visible within the community, but converting them to action is another challenge altogether.

Source: Center for Global Policy

Language: English

Date: 21 December 2020

‘Get Lost!’: European Return Policies in Practice

What does it say? A chapter focusing on conditions in Syria details the myriad barriers to return that persist despite the abatement of active conflict in much of the country.

Reading between the lines: In reality, Syrians contemplating return must navigate a set of new barriers as violence in the country transforms. Conflict has abated, but war-economy activities persist, petty crime is rising, and basic protections and dignity are absent.

Source: Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung

Language: English / German

Date: 1 October 2020

US Must Remove Sanctions and Allow Syria To rebuild – UN Expert

What does it say? The statement from Alena Douhan, UN special rapporteur on the negative impact of the unilateral coercive measures on the enjoyment of human rights, urges the lifting of the U.S. Caesar sanctions, which she contends prevent third-party engagement in Syria and much-needed rehabilitation and economic recovery.

Reading between the lines: The sanctions do have a clear chilling effect, and they forestall foreign engagement in Syria. That is precisely the point. The U.S. is unlikely to lift them without a major — currently unimaginable — concession from Damascus.

Source: UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

Language: English

Date: 29 December 2020

What does it say? The article chronicles the subsistence hardships facing Syrians as inflation wipes out spending power and drives producers to peddle their goods in neighboring markets.

Reading between the lines: Syrians are faced with a dilemma. The country’s worsening food crisis is linked to the fiscal and economic crises. Certainly, conflict conditions have reduced agricultural productivity, but more critical now is the fact that Syrians simply cannot afford many of the foods that make up the local market.

Source: Newlines

Language: English

Date: 23 December 2020

Turkish Intervention in Northern Syria: One Strategy, Multiple Policies

What does it say? The paper offers a detailed breakdown of Turkey’s varied tactical actions across zones of influence in northern Syria, all of which contribute toward a unified strategic aim.

Reading between the lines: High-profile debate over Turkey’s long-term ambitions for northern Syria masks the reality that these areas have become, in many respects, more Turkish than Syrian. Ankara will not surrender control without significant concessions from Damascus.

Source: European University Institute

Language: Arabic

Date: 21 December 2020

In Offering an Afghan Militia To Kabul, Iran’s Zarif Causes Outrage

What does it say? Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif has caused an uproar in Afghanistan after suggesting that Afghanistan redeploy the Iranian-supported Afghan fighters of the Fatemiyoun Brigades from Syria to Afghanistan.

Reading between the lines: The incident highlights the reality that the long-term persistence of violence in Syria will increase the likelihood of regional spillover effects.

Source: Middle East Eye

Language: English

Date: 23 December 2020

Russian Aid in Syria: An Underestimated Instrument of Soft Power

What does it say? The article takes a long view of Russian aid operations in Syria and notes the risks to principled donor-funded aid activity by other actors.

Reading between the lines: Not surprisingly, Russian aid activities overlap with Moscow’s overall tactical approach to Syria, making them a powerful tool of Russian soft power in the country.

Source: Atlantic Council

Language: English

Date: 14 December 2020

What does it say? The M4 highway in northeast Syria remains closed to commercial traffic following the escalation between Turkish-backed opposition forces and the SDF at Ein Issa.

Reading between the lines: The road has intermittently been closed and reopened since Turkey’s Operation Peace Spring, in October 2019. While alternate routes are available, the M4 has long served as the primary commercial artery of Syria northeast. Further changes in its status can be expected as long as Ein Issa is contested.

Source: Syrian Observatory for Human Rights

Language: Arabic

Date: 23 December 2020

The Wartime and Post-Conflict Syria project (WPCS) is funded by the European Union and implemented through a partnership between the European University Institute (Middle East Directions Programme) and the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR). WPCS will provide operational and strategic analysis to policymakers and programmers concerning prospects, challenges, trends, and policy options with respect to a conflict and post-conflict Syria. WPCS also aims to stimulate new approaches and policy responses to the Syrian conflict through a regular dialogue between researchers, policymakers and donors, and implementers, as well as to build a new network of Syrian researchers that will contribute to research informing international policy and practice related to their country.