‘National sovereignty’ is the latest barrier to procurement of the COVID-19 vaccine in Syria, which continues to run up against ill-defined hurdles, even as state health authorities admit that a long-running second wave of infections is wreaking havoc in the country. On 21 January, Syrian Minister of Health Hassan Ghabbash announced that the Ministry of Health (MoH) had not yet signed a deal with pharmaceutical companies or organizations to procure the COVID-19 vaccine, noting that the conditions presented thus far did not “suit” the Government of Syria. In a cryptic remark, Ghabbash stated that the Government of Syria “will not accept to procure the vaccine at the expense of other matters relating to the Syrian citizen and Syrian sovereignty.” Given the ambiguity of this statement, uncertainty over vaccine procurement in Syria is deepening as the country continues to plunge into uncontrolled community spread.

Consistently inconsistent

Ghabbash’s statement throws cold water on earlier claims by Syrian Foreign Minister Faisal Mekdad that negotiations were underway between the Syrian and Russian governments for the distribution of the Russian-manufactured Sputnik V vaccine in Syria. Likewise, the statement introduces questions over earlier claims that Syria would receive the COVID-19 vaccine commissioned by the World Health Organization (see: Syria Update 4 January 2021). Further complicating matters, the head of the Syrian Doctors Syndicate, Kamal Assad Amer, has delivered news that Syria will receive 2 million doses of the Russian and Chinese vaccines in April.

Throughout the protracted Syria crisis, authorities have played various interlocutors against each other in search of better outcomes. At bottom, the inconsistent statements that officials continue to make should be seen as an indicator of confusion and uncertainty over all matters related to COVID-19 in Syria. This includes vaccine procurement that will almost certainly hinge in large part upon international largesse. Meanwhile, the Government of Syria’s actions during earlier stages of the outbreak gives cause for concern. Personal protective equipment and medical supplies have not been distributed equitably to rural facilities, for instance, according to Human Rights Watch. The wealthy few and individuals with connections have reportedly been able to buy better care, sometimes avoiding overburdened public health networks altogether. At the time of writing, neither the WHO nor the Russian or Chinese government has commented on the statements.

Locals first?

The ambiguities of Syrian vaccine procurement have brought to the fore serious issues concerning equitable access and distribution to Syrian refugee communities in neighboring countries too. In Lebanon, news of progress toward vaccine procurement by the Lebanese state sparked immediate debate over prioritization and refugee access to health care. On 17 January, Lebanon finalized a deal with Pfizer and BioNTech to procure 2.1 million doses of the vaccine, which will reportedly reach Lebanon by February. This will be complemented by another 2.7 million doses from the COVAX program launched by the World Health Organization (WHO), while Lebanon’s private health sector is reportedly in discussions to purchase additional doses of the Oxford/Astrazeneca and Chinese Sinopharm vaccines. On 21 January, the World Bank also approved a reallocation of $34 million under the existing Lebanon Health Resilience Project to support vaccines in Lebanon.

Following these announcement, a hashtag has circulated on Twitter calling for the state to give priority access to Lebanese citizens, ahead of Syrian and Palestinian refugees. A top health official has stressed that people of all nationalities — not just Lebanese — must be vaccinated in order for the vaccination plan to work. However, concerns remain. Lebanon’s public health system has been battered by COVID-19. Public health imperatives have fallen by the wayside as public-private cooperation has faltered and both systems struggle against extreme financial instability. A comprehensive system for tracking and administering vaccine rollout will also be critical. It is unclear whether such a system exists in Lebanon. Moreover, Lebanon is a nation with a weak central government and powerful patronage networks that survive by channeling resources to their power bases. It is likely that vulnerable populations — including Syrians and Palestinians — will be left without strong advocates for vaccination and other relief. This is especially true for Syrians who are not formally registered as refugees, and who struggle to gain access to entitlements.

Leading by example

Meanwhile, Jordan has begun administering COVID-19 vaccines free of charge to everyone residing in Jordanian territory, including refugees and asylum seekers. UN High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi praised Jordan for including refugees in its national response plan to combat the virus and urged other countries to do the same. According to the UNHCR’s Public Health Section, including refugees, asylum seekers, and forcibly displaced populations in vaccine rollout plans is key to ensuring the end of the pandemic, as it is the only way to prevent further community transmission.

Logistical hurdles

The number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in Government-controlled areas in Syria has reached 13,313 as of writing, according to the Syrian MoH. Independent estimates put the number at more than 100,000, although accurate figures are impossible to pinpoint given data gaps and limited testing capacity. Nonetheless, anti-COVID measures are still not enforced in Government-controlled areas, and schools remain open. There are indications that Syria is experiencing a renewed wave of infections, with positive cases reported in Government-controlled areas soaring significantly since November 2020. With the absence of a clear governmental plan to obtain and distribute the vaccine, such numbers indicate a worrying trajectory. Furthermore, in the unlikely case that a vaccine were to be made available to Syria in the near future, logistical challenges to vaccination would be formidable.

Syria’s tripartite division, logistical challenges concerning storage and distribution, and hesitancy to interact with the state — a potential requirement for vaccination — are only a few of the challenges facing vaccine distribution in Syria (see: Syria Update 16 November 2020). Indeed, the latest uncertainty regarding the procurement of the vaccine proves that a widespread rollout will remain a challenge for months to come, particularly considering the absence of community protection measures. Cases are likely to continue to rise while the Government of Syria grapples with the challenge of forming a unified front to combat the spread of the virus. The Government of Syria has survived the conflict in large part by neutralizing opposition factions and limiting itself to a single front at a time. Although COVID-19 has witnessed a major reduction in hostilities, the state has struggled to focus meaningful attention on the pandemic response that is now its most important battlefront.

Whole of Syria Review

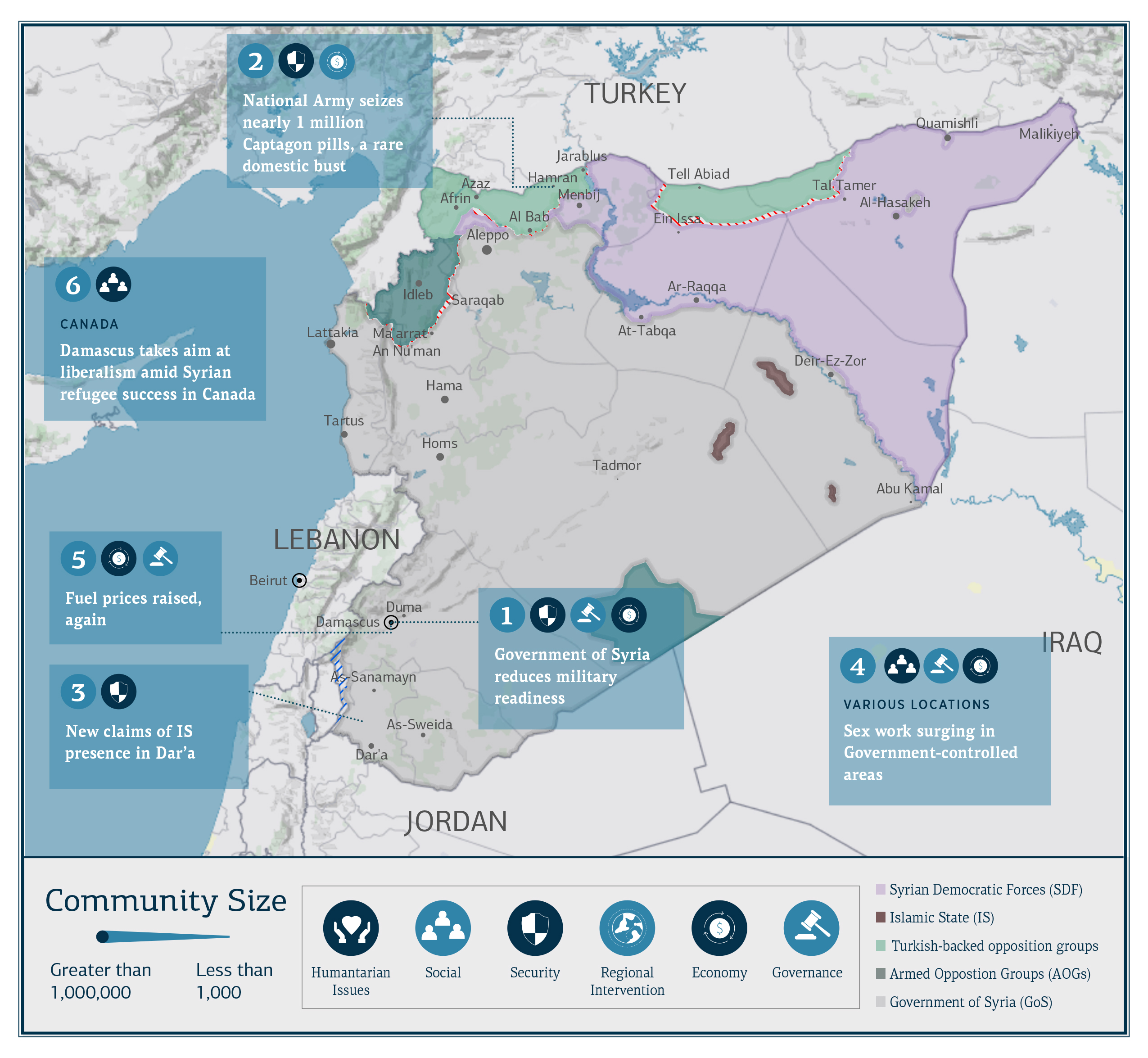

Government of Syria reduces military readiness

Damascus: On 10 January, media sources reported that the Government of Syria had issued a circular ordering the reduction of the Syrian Arab Army’s combat readiness and overall mobilization to pre-2012 levels. The order dictates that combat unit readiness be reduced from 80 percent to 50 percent, naval forces from 100 percent to 80 percent, and administrative units from 66 percent to 33 percent. Military hospitals were left untouched, with their readiness to remain at 80 percent. In practical terms, decreasing mobilization levels can be achieved by approving more leave days for soldiers and military personnel. The reduction has not been independently verified. Of note, it is reportedly supported by a decrease in ration allocations to military units, according to the circular.

Syria’s national army is not alone in scaling back its force readiness. Concurrently, media sources reported the dismissal of National Defense Forces (NDF) members in Deir-ez-Zor — specifically targeting those who refused to participate in the recent campaigns against Islamic State (IS) cells in the Syrian badiya (see: Syria Update 18 January 2021). Furthermore, in December 2020, Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif indicated that the Fatemiyoun Brigade, which predominantly consists of Afghan fighters, might be relocated to Afghanistan, ostensibly to participate in the campaigns against IS affiliates there.

A war Damascus can’t afford to win?

There are several likely causes of these reductions. These factors include the COVID-19 pandemic, the apparent desire of regional powers to halt major offensives, and grinding economic deterioration. If it is carried out, the reduction in rations to Syrian Arab Army units would be an indicator that cost-cutting is a factor. So, too, is the fact that major military operations in Syria have been effectively frozen since March 2020. As UN Special Envoy for Syria Geir Pedersen recently noted, the past 10 months have been the quietest since the outbreak of the conflict. In effect, reducing force readiness will allow combatants and military personnel more leave time. This may also satisfy the growing anger among soldiers and loyalist communities over leave requests and long periods of military service — which have, in some cases, stretched to a decade. That said, it is not clear whether the current initiative is in any way a response to social media campaigns by Syrian Arab Army soldiers demanding demobilization.

All told, reduced readiness may be a sign that economic desperation is changing the way the Syrian state operates, albeit by degrees. Looking ahead, the distinct possibility of resumed large-scale fighting in northwest Syria may trigger a reversal of the decision, and growing efforts to contain a re-emerging IS threat or unrest in southern Syria may also prompt a change of course. That said, it appears most likely that both local and foreign pro-Government forces will see a drawdown for the foreseeable future.

National Army seizes nearly 1 million Captagon pills, a rare domestic bust

Hamran, Aleppo Governorate: On 20 January, media sources reported that the Turkish-sponsored Syrian National Army’s (SNA) Third Corps had uncovered a shipment containing more than 900,000 Captagon pills in Hamran, a village near the frontline with Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)-held Menbij. Reportedly, the pills were concealed inside household heaters shipped into the northwest from Government-controlled areas. Local police forces in areas controlled by the SNA frequently announce arrests over Captagon and hashish smuggling, and they often link the trade to the Government of Syria, Iranian militias, and Hezbollah. Relatedly, local sources indicated that Jordanian border security had clashed with bedouin smugglers on 15 January, following an attempt to traffic Captagon across the border into Jordan.

Captagon: Center of the crime-conflict nexus

Conflict, destruction, territorial fragmentation, and sanctions have converged to make narco-trafficking a pillar of the Syrian economic landscape. The drug trade criss-crosses all zones of control. In fact, territorial fragmentation is a key factor allowing armed groups and narco-entrepreneurs to profit from drugs. That the drugs in this case were apparently bound for northeast Syria after transiting opposition-held areas is an indicator of the widespread nature of narco-trafficking networks in the country. Nonetheless, the Assad regime and its close military allies are widely believed to be the actors most influential in Syria’s Captagon industry. However, it is important to note that although the SNA has condemned the Government of Syria, Iran, and Hezbollah over the shipment, it is likely to re-sell the seized narcotics — according to local sources. It has ample incentive to do so. At current market prices in northwest Syria, the seized Captagon has a retail value of approximately $1.5 million. Fiscal considerations are also likely critical in southern Syria. The clashes and drug seizure at the Jordanian border are further evidence of how pervasive drug trafficking has become.

International data on drug busts in 2020 suggests that Syria is exporting Captagon at greater volume now than ever before. While stepped-up enforcement may improve interdiction in transit countries and foreign markets, little can be done to stem the tide of Captagon production or its trafficking inside Syria. In the long term, response actors must contend with the reality that Syria’s growing drug trade is unlikely to shrink, let alone disappear, until the conflict itself ends. Only through a combination of international pressure, calibrated incentives to eradicate narco-trafficking, and post-conflict economic recovery will key drug-trafficking networks become a liability, rather than a source of badly needed revenue. Until then, continued drug trafficking is all but guaranteed.

New claims of IS presence in Dar’a

Western Dar’a Governorate: On 13 January, Syrian Negotiations Commission President Anas al-Abdeh stated on Twitter that the Government of Syria and Iranian militias had “facilitated the movement” of more than 500 IS fighters and their allies to Dar’a in the past year. Claiming that the fighters are “soldiers of the regime, not their enemies,” al-Abdeh stated that continued instability in Syria gives pro-Government forces a pretext to reinforce positions in western rural Dar’a.

A southern insurgency?

The actual number of IS-sympathetic fighters in southern Syria is functionally impossible to establish, although the claim that 500 fighters have moved south with aid from Damascus is likely an exaggeration. Al-Abdeh’s statement comes without a clear prompt. Its timing may therefore reflect a hope of capitalizing on mounting attention to IS attacks elsewhere in Syria (see: Syria Update 18 January 2021). That said, IS has retained a presence in southern Syria since reconciliation. Local sources report (dubious) local rumors that the Government of Syria released dozens of members of local IS affiliate Jaysh Khalid bin Walid (JKW) from its custody in late 2019. Moreover, early 2020 saw renewed talk of JKW recruitment efforts in Dar’a, although it is not yet clear whether the rumors reflected any significant outcome on the ground (see: Syria Update 24 February 2020). Whatever their numeric strength, IS cells in southern Syria do threaten local stability, which is already challenged by tensions between the reconciled opposition and the Government of Syria. IS has, for instance, claimed responsibility for assassinations of Syrian government officials in the south.

The Government of Syria has limited capacity to impose stability on southern Syria. Absent a clear strategy or the will to carry it out, Damascus may instead hope that attacks carried out by radical actors in the area will be limited to small-scale, localized events that demoralize the reconciled opposition or give a pretext for a heavy-handed response by Government forces. Ultimately, the status of IS in southern Syria poses the same difficult-to-answer questions that are also raised in Syria’s eastern deserts: Where are IS cells based? How do they travel? Where are their weapons cached? And what are the vectors of recruitment and potential expansion?

Sex work surging in Government-controlled areas

Various locations: On 15 January, the Horan Free League published a provocative report detailing the dynamics of prostitution networks in Government of Syria–controlled areas. The report details the experiences of four female sex workers who were compelled to engage in sex work in Dar’a and Damascus for economic, security, and psychological reasons. It notes the particular livelihood needs experienced by widows, divorcees, and orphans, including one woman who was forced into sex work by her husband. Several details are especially noteworthy to the international aid response. The interviewed sex workers report that monthly income for sex workers rarely exceeded 25,000 SYP ($8.56), although some are able to secure other in-kind support (such as cooking gas) from clients. Women working with an elite clientele can reportedly earn as much as 100,000 SYP ($34.24) per month. Of particular note are claims regarding coercion, blackmail, and extortion. Women interviewed in the report cite instances of security officers abusing their power to drive women into prostitution.

Unsafe sex

The report highlights an often overlooked social issue that has grown in importance as conflict has eroded the rule of law in Syria and worsened economic destitution. Anecdotally, financial motivations have been a key driver of the reported growth in the sex industry, especially in Damascus and Rural Damascus, and in refugee camps, such as Jordan’s Zaatari Camp. Economically and socially marginalized women often have few livelihood opportunities, and are therefore at a structural risk of sexual exploitation. This is especially true given that no social, economic, or protection safeguards exist for vulnerable women and girls. To make matters worse, Syrian criminal law punishes female sex workers, while male clients seldom face legal consequences. One crucial aspect of prostitution is the involvement of security forces and informal militia groups. According to various media and local sources, prostitution networks are often protected by or linked to security and military figures, such as the National Defense Forces and the Military Intelligence. Suspected female sex workers and women detained for unrelated political or security reasons are often coerced into participating in prostitution rings run by security forces themselves. In addition to financial and direct participatory motivations, security-sector actors have political reasons to propagate sex work. Prostitution has been used as a cudgel to blackmail, extort, or even recruit. Protection and livelihoods programming may be effective bulwarks against coerced sex work on an individual basis, but the strucutral conditions that drive many women to sex work will not be resolved until Syria makes a sustained postwar economic recovery.

Fuel prices raised, again

Damascus: On 21 January, the Government of Syria’s Ministry of Internal Trade announced a 3 percent increase in the liter price of subsidized and unsubsidized gasoline, to 475 SYP and 675 SYP respectively. This comes after a string of previous price hikes, the most jarring of which was a 100 percent increase in fuel prices, implemented in October 2020, despite government vows not to reduce the vital support for subsidized consumables (see: Syria Update 26 October 2020).

New normal: Incremental increases

The stepped increase in the prices of subsidized goods is the new normal for the population of Government of Syria–held areas, heightening the existing challenges of making ends meet. This comes amid fuel shortages that are forcing vehicle owners to endure long fuel lines and pay considerable premiums for unsubsidized fuel (see: Syria Update 18 January 2021). In the near term, the increase will leave more Syrians without access to affordable public transportation, and fuel-dependent services, industry, and local production will see commensurate rises. Additional rolling fuel cuts, allotment reductions, increased fees for transit licenses (see: Syria Update 11 January 2021) can also be anticipated. In a climate of continuing consumer inflation — 13 percent for standard food baskets nationwide in December — small increases will have a big impact. In the long term, such measures are evidence of the state’s diminishing capacity and the shrinking of the social safety net (see: Syria Update 21 September 2020).

Damascus takes aim at liberalism amid Syrian refugee success in Canada

Canada: On 20 January, the Syrian Canadian Foundation organized a virtual gala celebrating the five-year anniversary of Canada’s welcoming of Syrian refugees. Attending the event were Syrian refugees resettled in Canada and dignitaries including Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Syrian-Canadian Omar Alghabra, Canada’s newly appointed transportation minister. The event marked five years since the first Syrian refugees landed in Canada, on 10 December 2015, as part of Canada’s Syria Operation, which has since reached its goal of settling 25,000 Syrian refugees from Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan in Canada by March 2016. Alghabra immigrated to Canada from Syria more than two decades ago and became the first Canadian minister of Syrian descent when he was appointed in a reshuffle on 21 January. His appointment went viral among Syrians on social media, as proof of Syrians’ potential and the community’s contributions to a host nation.

The Syrian culture wars

Issues such as the Syrian diaspora’s integration and accomplishments are especially sensitive to a community that is accustomed to persistently unflattering media attention. Since the peak of the refugee exodus, Syria has become synonymous with state collapse, the horrors of war, and urgent humanitarian need. There is a hope among Syrians that immigration and integration stories like those seen in Canada can inspire similar refugee-forward policies elsewhere. This is especially relevant at a time when various nations are assessing immigration policies for Syrians, particularly as they relate to the perceived stability of Government of Syria-held areas. At the same time, the Government of Syria’s response to the Canadian success story is also notable. Initially, Alghabra’s appointment was ignored by Syrian state television, which traditionally focuses on the harsh living conditions for Syrian refugees abroad, encouraging them to ‘return home’. State media ultimately criticized Alghabra, using his story in a bizarre non-sequitur to double-down on previous criticisms of social progressivism, equality, and what Bashar al-Assad recently described as a ‘neoliberal’ assault on Syria’s traditional values (see: Syria Update 14 December 2020). Syrian state television called Alghabra “a big supporter of homosexuals” and criticized him over an alleged plan to “build a mosque for homosexuals,” where the traditional invocation “God is great” would be replaced with the neologism “God is gay” (lit. “Allah ghay”). The somewhat puzzling turn should be seen primarily as political rhetoric. The embattled Syrian state is likely attempting to distract from its struggles to win a shooting war by waging a more winnable culture war. It is also further evidence of an emerging narrative within the Syrian state apparatus that traditional Syrian values and Islam itself are under assault by the West. The implicit suggestion is that Western democracy and social progressivism are unsuitable for Syria.

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below..

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

Government Issues Rare Tender to Export State-Made Cement

What Does It Say? The Government of Syria issued a tender to export thousands of pounds of cement at a price of 135,000 SYP per ton, while the black market price for a ton is 250,000 SYP.

Reading Between the Lines: Although the price of cement is rising in Syria, suggesting a shortage, the government is exporting. It could be that it is prioritizing its foreign currency reserves over local construction.

What Is Aboard International Coalition Trucks?

What Does It Say? Amid heightened crossborder conveys by U.S. forces, Syrian state media has accused the U.S. of siphoning off Syria’s resource wealth and trafficking in Syrian grain.

Reading Between the Lines: U.S. vehicle traffic between Iraq and Syria is a subject of frequent — often fervid — debate among analysts and within Syria. However, the state media claim that U.S. forces are using their presence in Syria to extract wheat are likely meant to lay the groundwork for blame-shifting as wheat and bread crises rise to a fever pitch.

Syria’s White Helmets Awarded £920,000 To Make PPE

What Does It Say? The White Helmets organization has made more than 2 million masks, face shields, and gowns as Syria faces a dire need for PPE.

Reading Between the Lines: The White Helmets’ pivot from emergency frontline aid to health sector manufacturing will meet critical needs, but it is driven in part by the slowdown in conflict conditions, which makes their primary mandate — temporarily — less relevant.

Reports of a Syrian-Israeli meeting, sponsored by Russia, to expel Iran

What Does It Say? Reportedly, Israeli, Russian, and Syrian officials met at Hmeimim airbase to discuss a number of topics, including Israel’s demand for the removal of Iranian troops from Syrian soil.

Reading Between the Lines: Neither Damascus nor Tel Aviv have mentioned anything about this meeting, casting the credibility of this report — already a dubious proposition — into further doubt. All told, the ouster of Iranian forces from Syria is highly unlikely, not least because Iran is a key ally of the Syrian regime.

What Does It Say? The Government of Syria’s electricity production has dropped to 2,800 megawatts, while demand stands at 7,000 megawatts.

Reading Between the Lines: Adequate electricity generation will likely remain elusive in Syria, not least because of supply shortages and recurrent outages and attacks on power plants. Current reports indicate that households in Damascus receive only one hour of electricity every six hours.

What Does It Say? The Biden administration has reportedly laid out four priority conditions for the SDF. These are: rapprochement with the Kurdish National Council; establishing communication with the Syrian National Coalition; reduction of tensions with Turkey; and discontinuing oil supplies to the Government of Syria.

Reading Between the Lines: The SDF’s trust in the U.S. has been shaken, yet northeast Syria’s leadership is savvy, and likely recognizes that U.S. abandonment is now unlikely. The U.S. and the SDF have independent objectives for the conflict, but both are in alignment on proximate goals. Medium-term cooperation is likely to be fruitful, but there are important questions over the compatibility of their respective long-term outlooks.

EU Puts New Syrian Foreign Minister on Sanctions List

What Does It Say? The EU has put the Syrian foreign minister, Faisal Mekdad, on its sanctions list.

Reading Between the Lines: Sanctions on high-ranking Syrian government figures are routine.

Biden To Nominate Samantha Power To Lead Foreign Aid Agency

What Does It Say? President Biden is expected to appoint Samantha Power, the former UN ambassador, as USAID administrator.

Reading Between the Lines: Under the Trump administration, the aid provided by the U.S. to the rest of the world decreased. With Biden taking office, that is expected to change, and many in the Syria response hope for a more coherent policy direction from Washington.