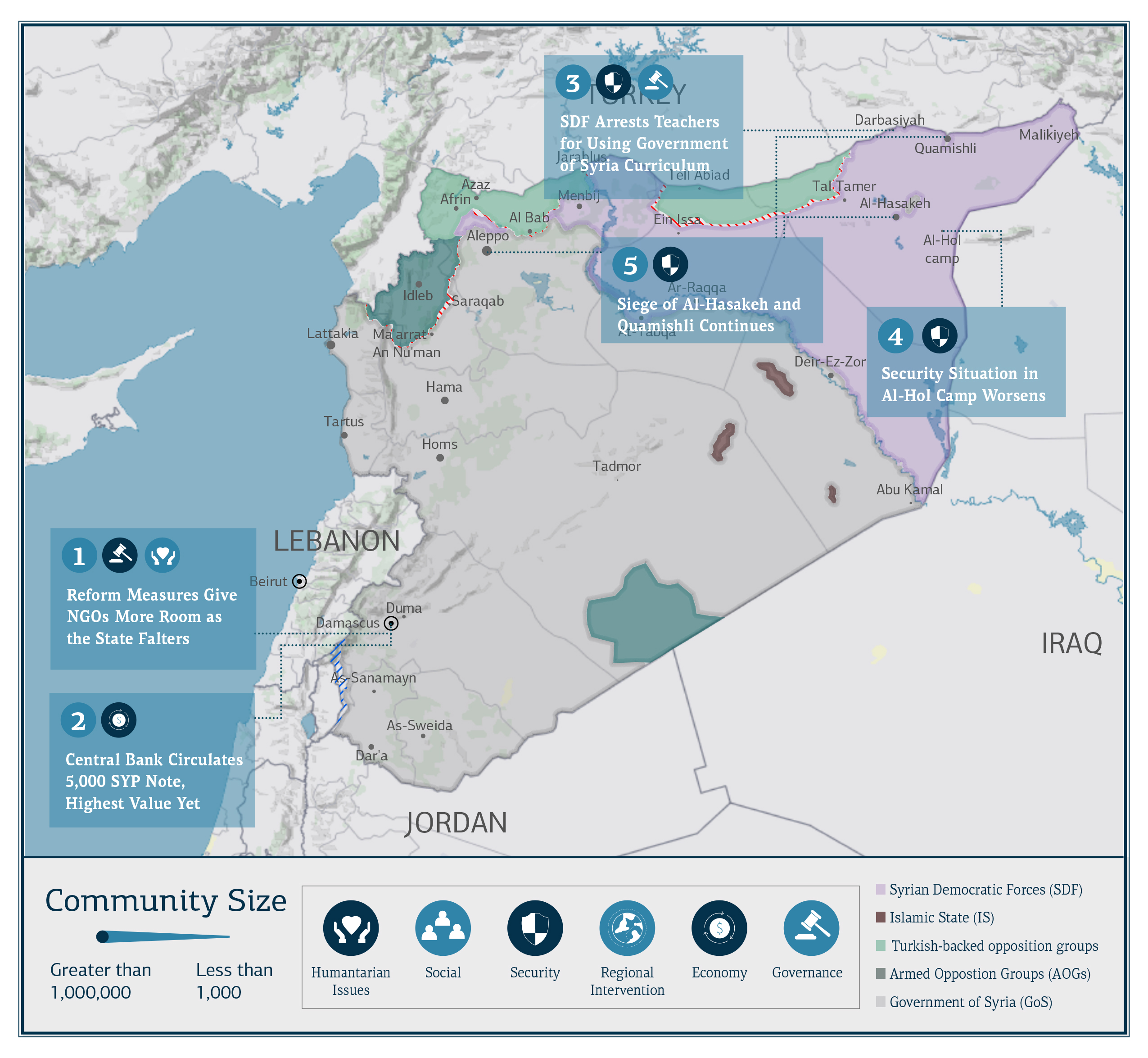

In-Depth Analysis

Tensions in southern Syria have flared as violent eruptions in the governorates of Dar’a and As-Sweida demonstrate two variations on the same themes: chronic instability and state fragmentation. Protests broke out across As-Sweida Governorate after Military Security officials ran roughshod over communal sensibilities by insulting a prominent Druze elder, prompting intervention from the Presidential Palace in an attempt to pacify the community and preserve a workable accomodation with the region. Meanwhile, in Tafas, Dar’a Governorate, a confrontation has emerged in response to the 4th Division’s demands that the Central Committee exile six unreconciled commanders of former rebel groups to opposition-held northern Syria. As of writing, neither of these flare-ups has been quieted.

The insult

On 26 January, the Druze community in As-Sweida burst into public protest in response to a convoluted chain of events that began with a detention in Homs. Government of Syria forces detained Siraj Sahnaoui, a 17-year-old from As-Sweida, without specifying a cause. In response, a powerful local intermediary, Druze Sheikh Hikmat al-Hijri, negotiated with Military Security head Louay al-Ali for Sahnaoui’s release. However, local sources indicate that al-Ali, when approached, mocked and insulted the Druze spiritual leader and the faith community as a whole. Sources indicate that Syrian President Bashar al-Assad had subsequently personally telephoned al-Hijri to apologise and guarantee Sahnaoui’s release.

The intervention did not immediately halt the tensions growing in As-Sweida, as protests against al-Assad and militias aligned with Damascus continued sporadically throughout the governorate. Earlier in the week, demonstrators across As-Sweida tore up posters of al-Assad and decried the upcoming 2021 presidential election as illegitimate.

Demonstrations against the Government of Syria are rare in As-Sweida. Above all, this latest incident highlights the state’s inability to rein in the all-powerful security services, which continue to act with seeming impunity despite a history of inflammatory actions and remarks. Indeed, this incident echoes the insults dealt out to local notables following the arrest and abuse of teenagers in Dar’a in March 2011 — an event widely credited with instigating Syria’s popular uprising. Although the heads of several security services were reshuffled in 2019, the services remain unreformed and seemingly unaccountable (see: Syria Update 4-10 July 2019). Reports indicating that al-Assad personally reached out to Hikmat al-Hijri demonstrate the extent to which Shuyoukh al-Aqel, the spiritual leadership of the Druze community, serves as an important local intermediary between Damascus and the community in As-Sweida.

The population of the governorate is said to be unsatisfied with the Government of Syria’s response to the situation; reports suggest that they have increased their demands, which now reportedly include a formal apology from Louay al-Ali to the Druze community and the resignation of al-Ali as the head of Military Security. On 28 January, another state delegation met with Hikmat al-Hijri alongside representatives from As-Sweida in an attempt to resolve their differences. However, the meeting once again failed to bring about a mutually agreeable outcome. Local representatives expressed their dissatisfaction with Military Security and accused the service of facilitating illicit activities — including the drug trade — and of seeding instability in the region.

As of writing, the escalation in As-Sweida remains unresolved. Given the upcoming presidential elections, the Government of Syria can ill-afford to anger the Druze community and shatter the illusion of popular support. For instance, the ouster of Syrian Prime Minister Imad Khamis in June 2020 was widely seen as a response to nationwide protests that raged most intensely in As-Sweida (see: Syria Update 15 June 2020). Given al-Ali’s perceived successes in southern Syria, his removal would come as a surprise. Should he remain in office, it will speak to the importance placed on security and intelligence figures above and beyond public servants.

Same but different

Some 50 km to the west, tensions intensified in Dar’a Governorate as the 4th Division increased pressure on the Central Negotiations Committee to relocate former opposition members to northern Syria and to facilitate the surrender of medium and heavy weapons. The week-long negotiations have yet to yield significant results, but the repeated deferral of deadlines suggests hesitancy on the part of the 4th Division to carry out threatened military action. On 24 January, the 4th Division shelled parts of Tafas, in western Dar’a Governorate, and clashed with local armed groups, resulting in the death of at least eight 4th Division fighters. The attack came as a direct result of disagreement between the 4th Division and the Central Negotiations Committee regarding the relocation of former opposition commanders and their families to northern Syria and the surrender of weapons to Government of Syria forces. The 4th Division’s demands also include: accommodating a direct 4th Division presence in Tafas; granting the division permission to carry out searches for IS suspects in the community (see: Syria Update 25 January 2021); and, finally, handing over all government buildings in the town to the Government of Syria. Notably, the former opposition members being requested to relocate to northern Syria remain unreconciled with the Government of Syria following its retaking of southern Syria in 2018.

Throughout the past week, the 4th Division and the Central Negotiations Committee have failed to reach an agreement: the latter rejected many of the former’s demands, especially those concerning the reinforcement of 4th Division forces in Tafas. On 25 January, following shelling and skirmishes, the 4th Division gave the committee three days to meet these demands, or a large-scale ground and aerial attack would be launched on Tafas. On 28 January, however, the three-day period was extended until 1 February. The extension of the deadline evinces the Government of Syria’s hesitancy to escalate in southern Syria. Given the extremely volatile nature of the area, it is yet to be seen how this incident will play out. The Central Negotiations Committee has taken a hard line, viewing acquiescence as a slippery slope. Surrendering weapons and relocating unreconciled fighters to northern Syria may avert an attack on Tafas, but there is a pervasive fear that doing so would open the door to more aggressive actions in the future. On 31 January, local media reported that the 4th Division had reduced its demands as negotiations continued. Meanwhile, local sources and media reports indicate that Tafas has witnessed civilian displacement over the past week, in anticipation of a potential military escalation.

Whole of Syria Review

Reform Measures Give NGOs More Room as the State Falters

Damascus: In late January, the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labour (MoSAL) issued a series of ministerial decisions aimed at re-organising the work of local humanitarian organisations and charity associations operating in Government of Syria–controlled areas. These decisions include:

- On 21 January, MoSAL prohibited senior-level personnel (i.e. executive board members, financial managers, and project managers) from engaging in simultaneous employment or volunteer work at multiple organisations. Furthermore, NGOs were banned from having more than one member of a family on the board. NGOs are not permitted to contract entities owned by relatives of board members and administrators (up to the fourth degree of relation). However, NGOs based in towns with extended familial ties are exempted from the latter regulation, and a maximum of two members from the same family will be allowed to serve on boards.

- On 21 January, MoSAL permitted local NGOs to sell goods produced through NGO projects directly in local markets, as a means of generating revenue. According to the decision, NGOs will need to obtain a permit from the Directorate of Social Affairs, which will allow them to use a special invoice book to account for receipts.

- On 26 January, MoSAL allowed NGOs to obtain a permit to collect donations for a period of one year — instead of the usual three months — purportedly as a means of providing NGOs with more space to raise funds.

- On January 26, MoSAL ordered social affairs directorates to establish a central database housing data on all NGOs in operation in their jurisdiction. This data would include NGO contact information and their timetables for receiving new beneficiaries. In theory, this system will empower directorates to receive new aid applicants and direct them to the most appropriate NGO, according to location and the assistance needed. The NGOs will reportedly be able to accept or deny potential beneficiaries referred by directorates according to their own selection criteria. According to MoSAL, the decision aims to increase coordination between directorates and NGOs, and to streamline aid processes while safeguarding beneficiaries’ time and dignity.

Shifting social welfare responsibility

The reforms package represents an expansive, albeit incremental, reworking of conditions for local aid operations and the relationship between organisations and the state. By opening the door to more local revenues, the measures will allow entities to grow their overall capacity to implement aid activities. This can be read as a natural response to the state’s shrinking capacity to provide social welfare, a fundamental pillar of Syria’s historical governing compact. Measures to allow local organisations to fill this gap are an important bulwark against rising needs, but they also pose sensitive questions about the relationship between aid actors and the state. This is of paramount concern as the state itself falters and shifts from direct service provision to a supervisory role: regulating, monitoring, and coordinating social welfare activities. MoSAL may yet take additional steps to centralise beneficiary selection and financial transactions; such changes carry obvious risks for beneficiary protection, humanitarian principles, and data security.

If implemented as advertised, MoSAL’s newly announced anti-corruption measures will have a positive impact in terms of transparency and favouritism in the aid sector in Government-controlled areas. However, the concrete rules that govern aid activities in Syria are no more decisive than are informal realities concerning access and permits, especially in instances where activities challenge the interests of influential stakeholders. MoSAL’s capacity to implement genuine reform vis-à-vis powerful NGOs, especially those led by influential figures, is in doubt. More centralised needs-assessment and beneficiary-selection processes led by the social affairs directorates in each governorate may indeed combat favouritism, but they also raise the risk of aid diversion.

The reforms follow an agenda set by Minister of Social Affairs and Labour Salwa Abdullah, who has taken a more open approach toward local civil society organisations since her appointment, in March 2020. Abdullah is a member of the central committee of the Arab Socialist Union Party, a minority political party whose strength is eclipsed only by the Ba’ath Party itself. Abdullah’s background may trigger resistance to the reforms, especially within Ba’ath Party circles or other government institutions.

Central Bank Circulates 5,000 SYP Note, Highest Value Yet

Damascus: On 25 January, Syrian state media reported that the Central Bank of Syria began circulating a new 5,000 SYP banknote. It is the largest denomination bill in Syria and the first new banknote to enter circulation since the release of the 2,000 SYP note, in 2017. The Government of Syria stated that its aim is to maintain a steady money supply while reducing the number of bills needed to purchase goods and pulling from circulation tattered low-denomination banknotes. The release is essentially a stopgap necessitated by soaring inflationary pressures. Although the 5,000 SYP note is the highest ever to be distributed by the Government of Syria, its market value is approximately $1.65.

Clapback has been swift. The bill’s release prompted money exchange shops in Al-Hasakeh to cease operation, fearing a rapid collapse of the Syrian pound. The Syrian Interim Government has issued an order banning the new banknote; it also reaffirmed its previous ban on circulation of the 2,000 SYP note in its areas of influence. Interim Government authorities have mandated that consumers deal in Turkish lira, although both currencies continue to circulate in areas under Interim Government control.

Runaway inflation fears

The circulation of a new, higher denomination banknote has been seen as an inevitable manifestation of the inflation that has sharply eroded Syrians’ purchasing power. Critics of Syrian fiscal policy have voiced concerns that a higher value banknote will now turbocharge a vicious inflationary circle. In other contexts, there is limited evidence that introducing a higher face-value banknote alone drives inflation. In a television interview, Deputy Minister of Finance Riad Abd al-Raouf stated that the 5,000 SYP note is meant only to reduce the number of bills required to make everyday purchases. That said, Syrians are skeptical of assurances that the Central Bank of Syria will not pursue patently inflationary policies, such as increasing the money supply by printing money.

Since the new banknote was announced, the exchange rate has dipped to 3,040 SYP/USD, a six-month low. Traders have reportedly responded by raising the prices of goods. Cooking oil and sugar prices have jumped by 8 percent and 20 percent, respectively. Even a small rise can have a significant impact, as the status quo is already untenable. Food prices rose 236 percent nationwide in 2020, according to WFP. The use of foreign currencies may represent a check on currency collapse in outlying areas of Syria. Continued inflation and market instability are among the pressures that are driving Syria toward greater economic and political fragmentation (see: Cash Crash: Syria’s Economic Collapse and the Fragmentation of the State).

SDF Arrests Teachers for Using Government of Syria Curriculum

Darbasiyah, Al-Hasakeh Governorate: On 20 January, local media sources in eastern Syria reported that Asayesh forces had arrested six teachers in Darbasiyah, northern Al-Hasakeh Governorate, for teaching the Government of Syria’s curriculum in private lessons. The following day, teachers and students protested in the city, demanding the release of the arrested teachers. The Asayesh cracked down on the protest, arresting several more individuals. The Kurdish National Council (KNC) released a statement condemning the arrests and claiming that the teachers’ detention contravened an agreement previously reached between the KNC and the Democratic Union Party (PYD), which allows students and parents to choose their curriculum until an alternative recognised by UNICEF is developed.

Curriculum chaos endangers the future of thousands of students

Education in northeast Syria has — since the establishment of the Self-Administration — been a battleground on which struggles over ideology, identity, historical memory, and political power have played out. Naturally, aid actors must bear these sensitivities in mind. The Self-Administration introduced a novel curriculum in early 2015, gradually expanding its compulsory use through 2017. However, the Government of Syria’s curriculum is widely seen as a necessary stepping stone to higher education and future employment in Syria. Pupils and parents alike fear that without requisite Damascus-approved credentials, students will be unable to access these opportunities. Schools that have continued to employ the Government of Syria’s curriculum have frequently been targeted by Self-Administration security forces. The fact that the Self-Administration’s educational program remains unrecognised in Government-held Syria or abroad is a major issue, as is its failure to accommodate the cultural and ethnic sensitivities of various minority populations across the northeast.

A considerable number of students in northeast Syria continue to commute daily to Government-run schools located within the security squares in Quamishli and Al-Hasakeh. These students’ families accept the cost and inconvenience of such an arrangement as the price they must pay to avoid gambling with their children’s futures. This raises significant social cohesion and political stability questions. All told, the education sector continues to be an area of clear politicisation, given the recent tensions between the SDF and the Government of Syria over students’ mobility and access to schools in the currently besieged Government-controlled neighborhoods of Quamishli and Al-Hasakeh. Finally, the spat between the rival KNC and PYD factions shows that issues such as education can have an impact on questions of wider political importance.

Security Situation in Al-Hol Camp Worsens

Al-Hol camp: On 21 January, the United Nations reported that “disturbing events” at al-Hol camp were threatening aid activities, after 12 residents (Syrian and Iraqi) were reportedly killed in the first 16 days of January. On 22 January, the Self-Administration’s Office of Displaced People and Immigrants released its own statement, claiming that al-Hol camp suffers from capacity issues and pressing local challenges, including attempts to revitalise IS inside the camp. “This tragedy affects all the world,” the statement said, “and it is necessary to provide assistance and support to the [Self-]Administration as an aspect of responsibility sharing.” The statement asserted that security forces had foiled multiple attempts to smuggle weapons into the camp, and it blamed Turkish military activities as an aggravating factor in the apparent IS resurgence in the region.

Camp conditions continue to cause concern

Conditions at al-Hol are indeed concerning, and the reported deaths of a dozen residents are especially so. The Self-Administration has attempted to link troubling conditions in al-Hol camp — and radicalisation, in particular — to Turkey’s military operations, but this claim is spurious. Substandard living conditions, inefficient service provision, limited aid access, and pre-existing social stigma are all drivers of radicalisation in al-Hol. However, perhaps the most significant unaddressed challenge is the inability of camp management to limit or mitigate residents’ exposure to radical ideology. Preventing already vulnerable residents, especially children, from being exposed to IS ideology should be a priority, even as longer term solutions — including local return, resettlement, and foreign repatriation — await sufficient consideration.

The camp’s future trajectory will be shaped by two intersecting trendlines: the return of Syrian camp residents to their places of origin and the retention of perceived radicals and foreign nationals. The easiest cases to resolve are likely for Syrians from areas now under Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) control. As their cases are resolved, the camp population will skew more foreign, and the proportion of residents holding potentially problematic ideology will inevitably grow. Though the SDF has taken steps to facilitate the return of Syrian camp residents, Iraqis and other non-Syrians make up around 63 percent of the camp’s population (see: Syria Update 12 October 2020). Foreign nationals — except for those who manage to smuggle themselves out — will likely remain in the camp until an effective repatriation mechanism is operational. In the interim, al-Hol will continue to face severe challenges, and Self-Administration officials are likely to continue pressing for international support.

Siege of Al-Hasakeh and Quamishli Continues

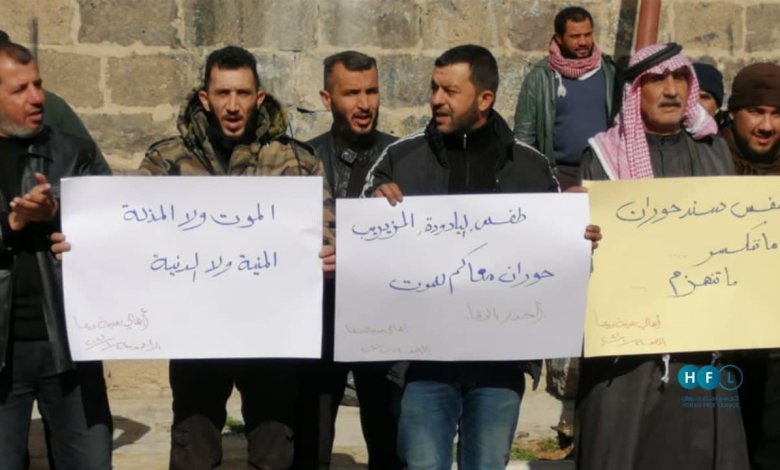

Al-Hasakeh, Quamishli, Aleppo: On 27 January, local media sources reported that the SDF’s besiegement of Government-controlled enclaves in the cities of Al-Hasakeh and Quamishli had entered its third week (see: Syria Update 18 January 2021). At the time of writing, the siege continues, as does the Government of Syria’s retaliatory siege on the predominantly Kurdish Sheikh Maqsoud neighborhood of Aleppo city. Protests against the SDF sieges have been staged by residents of the affected areas in Al-Hasakeh and Quamishli, with the participation of tribal leaders and clan elders. It was reported that the SDF fired bullets into the air to disperse protesters. Relatedly, on 23 January, media sources reported that additional Russian forces had arrived at the Quamishli airport, for deployment in northeast Syria. According to the reports, the Russian reinforcements are meant to bring stability to areas in northeastern Syria; this is rumoured to be part of a pressure campaign against the SDF. As of writing, local sources indicate that the Russian reinforcements have not yet left the Quamishli airport.

Two entities can besiege, but only civilians will suffer

That the sieges have continued with little change in status fuels questions over the two sides’ demands and their ultimate de-escalation strategies. Neither party has clearly defined its goals, complicating any attempt to forecast a resolution to the events. Additional uncertainty is introduced by the stalemate in SDF-held Ein Issa, where Russia has sought to leverage Turkish military pressure to force the SDF to hand over control of the town (see: Syria Update 7 December 2020). Potentially more conseuqential is the string of weekend bombings in major cities in Turkish-influenced northern Aleppo. SDF-sympathetic cells are routinely blamed for destabilising attacks in these communities, ostensibly as a challenge to Turkey (more on these late-breaking attacks will follow in the upcoming Syria Update). The arrival of Russian forces in Quamishli has been portrayed as a significant move and a potential signal of Russia’s willingness to bring more pressure against the SDF as it pushes for a disengagement in the security squares (and the handover of Ein Issa). However, it is difficult to imagine the Russian presence tipping the balance. Meanwhile, Russian media have accused the SDF of preventing food from entering besieged areas in Al-Hasakeh and Quamishli since the sieges began, earlier this month. Service and mobility interruptions are likely to persist in all the affected communities.

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below..

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

U.S. Strategy in Syria Has Failed

What Does It Say? Former U.S. Ambassador to Syria Robert Ford lays out the case for why the Trump administration’s most high-profile state-building project — that in northeast Syria — failed, and with it the rest of American Syria strategy.

Reading Between the Lines: The article calls attention to a reality that aid actors often overlook: the whole-of-Syria impact of concerted support to northeast Syria.

‘Trouble Spots’ Exploding in Front of the Syrian Regime

What Does It Say? Tensions erupted into open protest in several parts of Government-held Syria, likely due to poor living conditions.

Reading Between the Lines: Analysts searching for local triggers of violent outbursts can miss the forest for the trees: As in the current cases, common conditions can be a factor in protest and unrest in Syria, even in vastly different areas.

What Does It Say? In general, Syria’s 2020 was quieter than previous years, with diplomatic efforts and economics taking the spotlight.

Reading Between the Lines: The reduced pace of action in 2020 can be attributed to a large extent to the COVID-19 pandemic, which halted all major military activity.

What Does It Say? The article contains a table listing the most prominent HLP laws issued in Syria since 2011.

Reading Between the Lines: HLP laws increasingly benefit people close to the Government of Syria; those who aren’t well connected often face explicit and implicit barriers.

What Does It Say? The study outlines the prerequisites for an election deemed to be fair by the displaced people of Syria, basting doubt on the upcoming presidential election.

Reading Between the Lines: This is the position adopted by most of the international community, but decision-makers will have to retool their approach to match ground realities given the likelihood that al-Assad will coast to re-election.

From Dubai to Damascus: Filipinas Talk About Rape and Imprisonment in Syria

What Does It Say? The report outlines the stories of Filipinas en route to Dubai who were caught in a human trafficking ring and sent to Syria to work as maids. Many of them were not paid and were subjected to sexual and physical violence by their employers.

Reading Between the Lines: The illicit economy of Syria is continuing to grow, and illict economies including human trafficking have long been a feature of this landscape.

IDPs in Northwest Syria: New Winter, Old Ordeal

What Does It Say? The article is a visual document showing the camp flooding in northwestern Syria, an annual ordeal facing millions of Syrians in the winter season.

Reading Between the Lines: The yearly repetition of this grim cycle is a reminder of the potential mismatch between emergency humanitarian modalities and the chronic needs arising from a long-term protracted crisis.

Ar-Raqqa’s Sednaya: Stories of Syrians Who Escaped Death Under Torture in Ayed Prison

What Does It Say? The report lays out the stories of torture and abuse experienced by inmates in SDF prisons, which is very similar to that experienced by inmates in Government-run prisons.

Reading Between the Lines: The Government of Syria is often reprimanded for its inhumane treatment of its prisoners, but the report is a reminder — by no means the first one — that abuse is not limited to a single side in the conflict.

Fragmentation and Perceived Bias: The Shortcomings of US Policy Towards Tribes in Syria

What Does It Say? The article lays out several key challenges that made eastern Syria’s tribes a difficult local partner, and it describes the missteps made by the coalition in turn, reducing overall effectiveness and creating risk for tribes themselves.

Reading Between the Lines: Leveraging the power of Syria’s tribes has been an important component of nearly every outside power’s influence strategy for eastern Syria. Several years into the International Coalition’s presence in Syria, it has yet to land on a workable approach.

What Does It Say? Militias are exploiting the deteriorating economic situation to recruit youths in As-Sweida.

Reading Between the Lines: The catastrophic economic situation in Syria has made militia work one of the only reliable forms of income.

Around 70 Percent of Households Depend on Remittances

What Does It Say? Most families in Syria are dependent on remittances from abroad.

Reading Between the Lines: In a troubling catch-22, tightening restrictions on make it even harder for families dependent on money from abroad to access this lifeline.