In-Depth Analysis

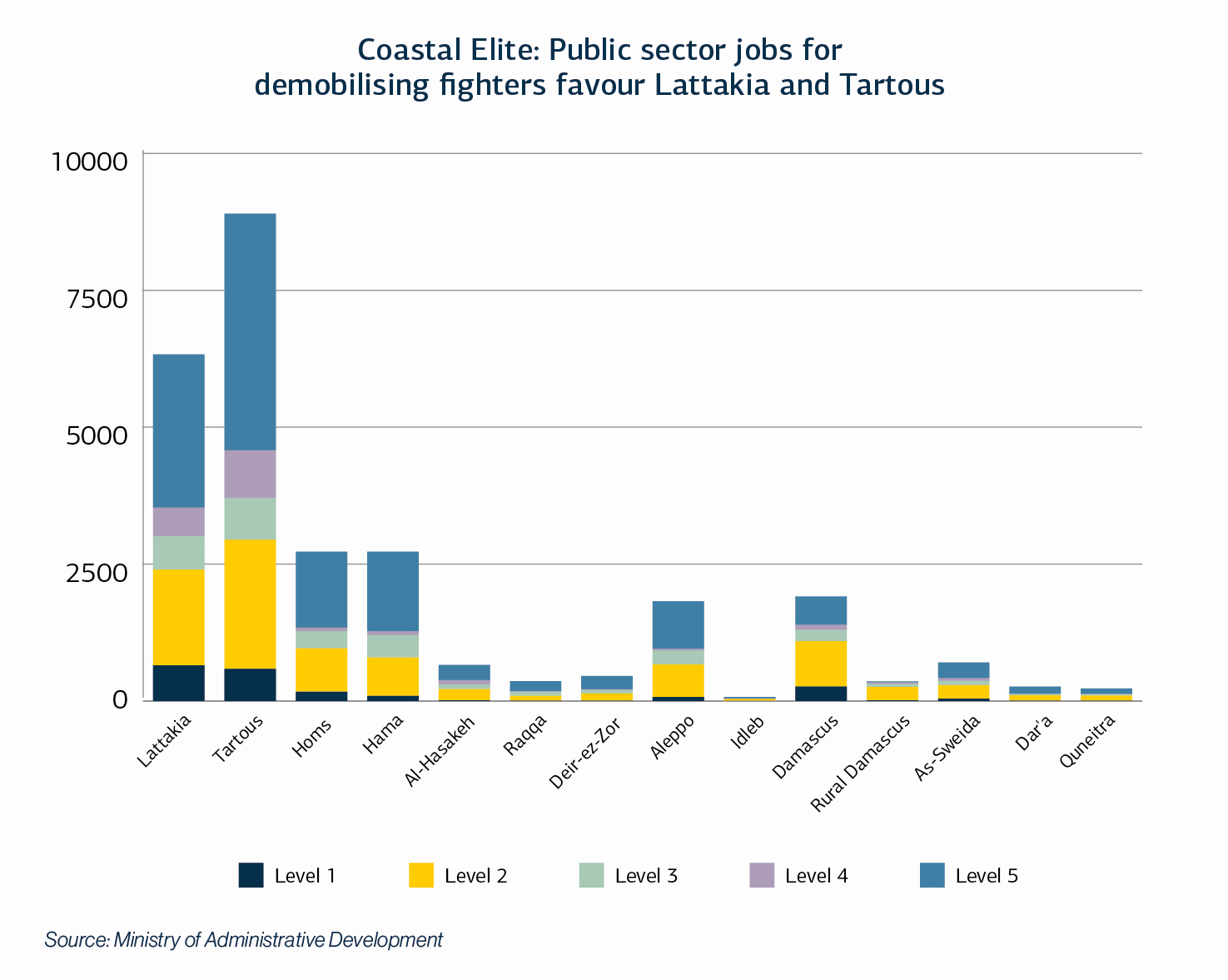

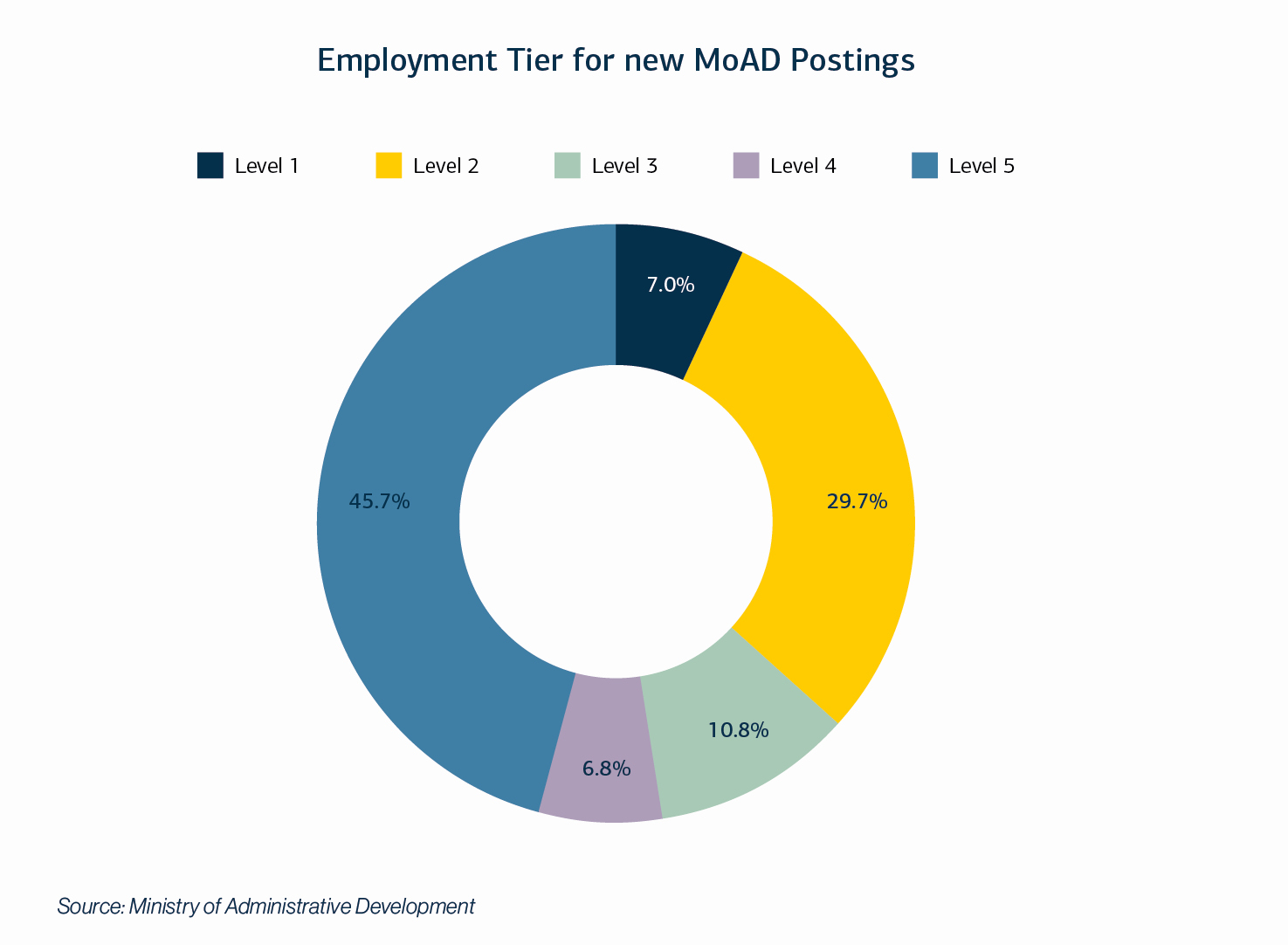

On 30 January, the Ministry of Administrative Development (MoAD) announced that 10,076 demobilised Syrian Arab Army soldiers had passed the employment exam taken by candidates for the two topmost tiers of public-sector work. While the employment pipeline directing demobilised soldiers into public service is not new, it has arguably never been more important in Syria’s modern history, and it is changing significantly. Currently, this employment system is undergoing a quiet transformation through unprecedented vacancy levels and structural changes employed to keep former soldiers on the state’s payroll, as other, more attractive labour and livelihood opportunities dry up (see: The Syrian Economy at War Labor Pains Amid the Blurring of the Public and Private Sectors). Not surprisingly, geographic and demographic concerns have also arisen as preferential treatment for certain demobilised fighters has come into sharp relief.

From frontlines to front offices

Barriers to enter public service in Syria are falling. Public-sector salary tiers scale with workers’ education levels, yet nearly every jobseeker passed the latest rounds of exams, suggesting that the test itself is no longer a tool for discerning worker aptitude and fitness for state jobs. The latest changes suggest that the Government of Syria is prioritising measures to placate former fighters over efforts to fill its civil ranks with trained bureaucrats. For the top two tiers (open only to applicants with university degrees, two-year degrees, or secondary school certificates), 10,076 jobseekers passed the exam, out of 10,136 test-takers. On 6 February, the MoAD announced that 100 percent of an additional 18,000 demobilised soldiers had passed exams for lower-tier employment. All employees will receive six months of paid vocational training by their employer institutions, as per Ministerial Decision No. 55 of 2020. Perhaps most importantly, Basil Hayder, the head of the Institutional Organisation Department at the ministry, stated that for the first time, applicants will be allowed to state their preferences regarding the type and location of their employment. Previously, applicants entered a general labour pool administered by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labour (MoSAL), and they were liable to be sent to remote or undesirable postings.

It is not immediately clear what impact the apparent shift in administrative responsibility from MoSAL to MoAD will have. However, it is clear that the benefits conferred by the latest systemic changes have not been evenly distributed. Of the latest applicants, more than 55 percent are originally from Syria’s two coastal governorates, Tartous and Lattakia, or currently reside there. This coastal area comprises the socio-religious, political, and economic hub of the Assad regime, and it has arguably been the area least directly affected by conflict in all of Syria. Tellingly, governorates that were boiler rooms of the opposition — Dar’a, Quneitra, Deir-ez-Zor, Ar-Raqqa, and Rural Damascus — account for less than 10 percent of all jobs now being handed out under the demobilisation program. In addition to this favouritism, the move to allow workers to choose their areas of service may harden social and regional boundaries and reinforce the mutual suspicions that exist across Syria’s regions. Additionally, applicants from Tartous and Lattakia account for an outright majority of Tier 1 and Tier 2 positions. As a result, coastal office-seekers will bring home larger salaries and gain a tighter grip over Syria’s civil bureaucracy.

A safety net, but with many holes

Although a wider impact is not yet clearly visible, these changes may bring an end to the aid programs implemented by the Government of Syria to support demobilised, discharged, or wounded soldiers and auxiliary forces. In February 2019, the Programme for Supporting and Empowering Demobilised Soldiers was officially added to the National Social Aid Fund (established by Law No. 9 of 2011); it was extended for another year in May 2020. Currently, soldiers receive 35,000 SYP per month for one year following their demobilisation. Under the same program, wounded auxiliaries (i.e. local militia group members) receive 60,000 SYP monthly. Benefits paid out under the system are to be discontinued if former fighters find public- or private-sector work. Currently, the minimum monthly wage in the public sector is 37,000 SYP (approx. $12). However, demobilised and wounded fighters (including members of local militia groups) will continue to benefit from other privileges, such as “wounded of the nation” cards, which entitle cardholders to preferential medical treatment, university seats, and financial grants and loans. Moreover, on 1 February, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad waived wounded soldiers’ debt on bank loans up to 5 million SYP.

Flip side of the coin

While the Government of Syria is clearly seeking to make former soldiers more reliant on the state for continuing support, it has also shown its continued willingness to punish dissent and extract revenues where it can. On 2 February, Colonel Elias al-Bitar, the head of the army’s Exemptions and Reserves Branch, stated publicly that an amendment to Law No. 31 of 2007 allows the Government of Syria to confiscate the assets of those who refrain from entering military service — and the properties of their relatives (children and parents) — even when they age out of the requirement at 42, if they fail to pay the waiver fee of $8,000. The claim sparked public outcry. Observers note that the amendment stipulates that asset confiscation applies to military deserters only, while Law No. 35 of 2017 allows the Government to freeze the assets of a deserter’s spouse or children until it is established that the assets do not legally belong to the deserter himself. Bitar’s statement is in line with the Government’s approach to extracting revenues from other segments of the Syrian populace, especially refugees. Yet, it is not clear if Bitar’s interpretation reflects maximalist jurisprudence and authorities’ new interpretation of the law, or if it was merely a misstatement. In the absence of formal clarification, many Syrians assume the worst. Draft dodgers abroad may see the announcement as a warning that, unless they themselves pay up, their relatives inside Syria stand to suffer even greater losses.

Whole of Syria Review

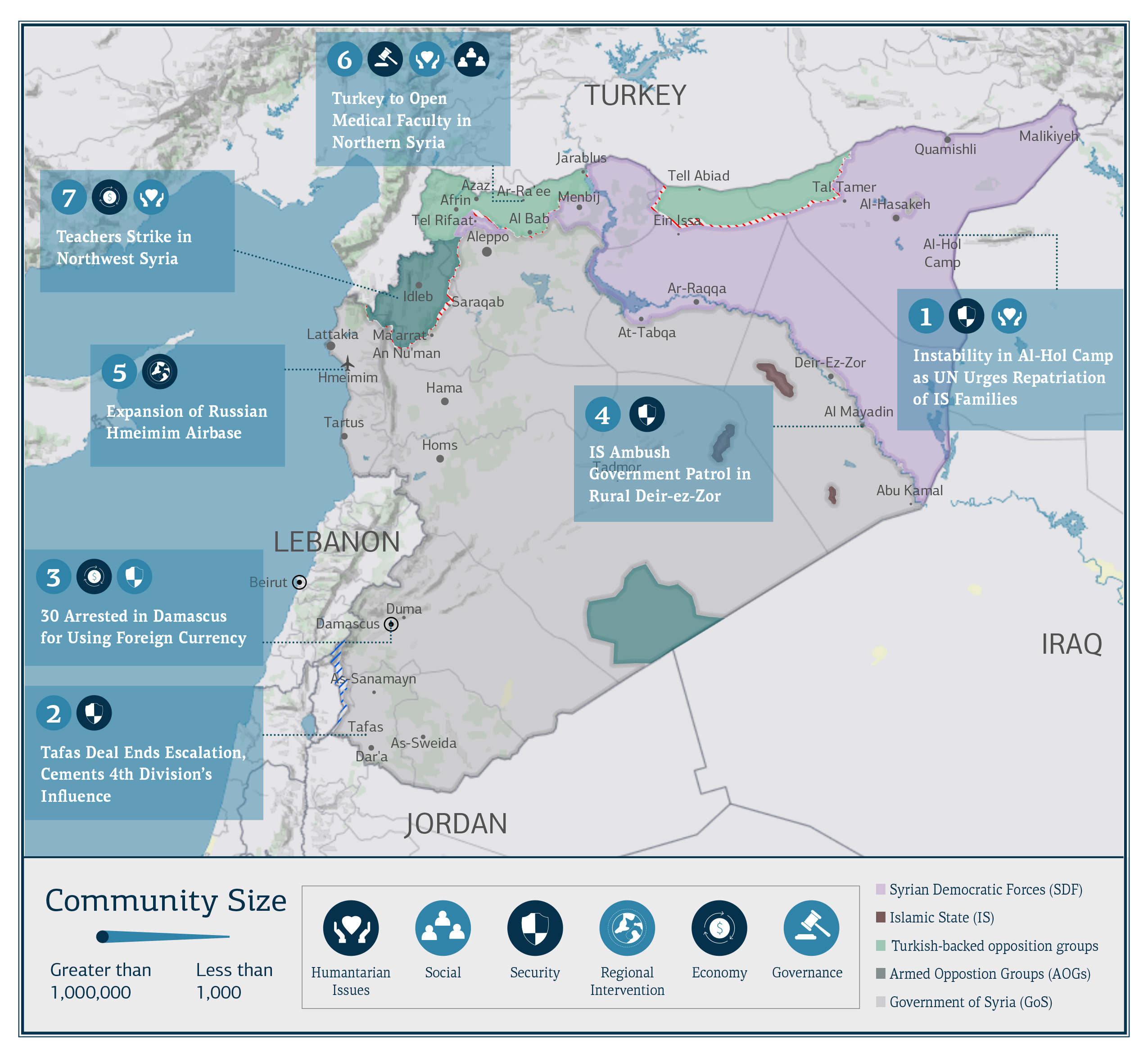

Instability in Al-Hol Camp as UN Urges Repatriation of IS Families

Al-Hol camp, Al-Hasakeh Governorate: The Quamishli-based research outlet Rojava Information Centre has reported that at least 20 people have been killed in al-Hol camp since the beginning of the year, including 10 who were reportedly beheaded. Responsibility for these killings remains unclear, but the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)–linked Asayesh, which is in charge of securing the camp, claimed that IS sleeper cells were behind most of the deaths. On 8 February, the SDF announced it had dismantled an IS network in al-Hol that was responsible for smuggling IS members and families from the camp.

Meanwhile, a group of outside expert investigators, led by Fionnuala Ní Aoláin, UN special rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights while countering terrorism, has urged 57 countries to repatriate their nationals, including families of suspected IS fighters, from “squalid camps” in northeast Syria. The appeal singles out at least 13 EU member states, the U.S., and the UK. The experts noted that camp residents are exposed to “violence, exploitation, abuse and deprivation in conditions and treatment that may well amount to torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment under international law.” According to the statement, an unverified number of camp residents have died “because of their conditions of detention.” The expert panel expressed concern over limits on humanitarian access to the camps and the emphasis on security-forward approaches, including in data collection, which has raised concerns over a duty of care toward beneficiaries.

From bad to worse

Conditions in al-Hol camp, resident repatriation, and potential deradicalisation interventions are matters of paramount concern for the international aid community and for local authorities in northeast Syria. By mid-January, a reported 12 killings in the camp evinced an alarming deterioration in internal conditions that has evidently persisted (see: Syria Update 1 February 2021). There is cause for concern that violence in al-Hol will beget further violence. Approximately 35 people were killed in the camp in all of 2020. Reports of beheadings — which have yet to be confirmed by sources outside the Self-Administration’s sphere of influence — are especially notable. If confirmed, such incidents would bear the hallmark of IS-linked actors. Yet, it is crucial to approach such reports with caution. Though a very real threat in its own right, IS has long been a rhetorical focus of northeast Syria officials keen to secure the international community’s support for a swift resolution to the situation in al-Hol camp.

As of October 2020, al-Hol, the largest displaced persons camp in northeast Syria, hosted approximately 64,619 residents, mainly women and children. Syrians and Iraqis account for 85 percent of residents, while other foreign nationals accounted for 15 percent of residents at that time. Repeated calls for the camp’s dissolution prompted the SDF to announce its intention to clear and release all Syrian families sheltering there late in October (see: Syria Update 12 October 2020). However, since that announcement, it is estimated that only 500 residents have left al-Hol. Although the SDF has advertised its efforts to ease resident return, including reportedly ending tribal-sponsorship requirements, myriad impediments remain. For many residents, dismal conditions in communities of origin mean they are unwilling or unable to return. Many Syrian camp residents originally from Deir-ez-Zor, for instance, are unable to return to their home communities because their houses have been destroyed, basic services are extremely limited, and livelihood opportunities are virtually nonexistent. That some of these same communities lie adjacent to northeast Syria’s oil wealth has only sharpened the local population’s sense of grievance, creating further risks in those communities, inside al-Hol, and across the Self-Administration more widely. Meanwhile, widespread concerns over the humanitarian situation in al-Hol camp persist, amid fears of IS resurgence and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Tafas Deal Ends Escalation, Cements 4th Division’s Influence

Tafas, Dar’a Governorate: Local and media sources have indicated that, on 8 February, the Central Negotiations Committee and the 4th Division reached an agreement to end the recent military escalation in western Dar’a Governorate (see: Syria Update 1 February 2021). With Russian mediation, the Western Central Committee (a group of notables from western Dar’a) and the Security Committee (a group comprised of Syrian Arab Army, including the 4th Division, and various intelligence service actors) hammered out an agreement allowing the 4th Division to search farms and confiscate medium weapons, provided no one is arrested in the process. Notably, the agreement forestalls the need to exile any wanted individuals to northern Syria, a key demand previously made by the Government of Syria. Nonetheless, the 4th Division has continued to expand its physical presence, mobility, and authority in western Dar’a, installing new checkpoints, opening new headquarters, and controlling important road access in the area. In another clear indication of its expanding influence, the 4th Division is now able to levy taxes on local militias’ smuggling operations.

A possible inflection point

The 4th Division’s approach to western Dar’a has been predicated on consistent application of pressure, maximalist threats, and patience as it has secured piecemeal agreements to expand its presence. Local sources note that the latest agreement came only after the 4th Division had obtained its apparent objectives by installing checkpoints and gaining control over main roads in the area. Meanwhile, a narrative circulating within Dar’a suggests that the latest deal is a success that will prevent a violent flare-up indefinitely. The true impact of the bargain is unlikely to be felt in the immediate term. However, it is distinctly possible that the 4th Division will find itself on surer footing when regional unrest flares. It is possible that the deal will result in a superficial restoration of key government institutions in western Dar’a, but the most meaningful impact on the ground is likely to be the expansion of the 4th Division’s security presence and influence.

30 Arrested in Damascus for Using Foreign Currency

Damascus: On 10 February, Government of Syria Military and Criminal Security branches raided several markets in Damascus city, including al-Hariqa, al-Hamidiyah, and Marjeh, arresting 30 people for trading in U.S. dollars. Media sources reported that the raids targeted electronics and phone shops, which are notorious for dealing in foreign currencies due to the import-based nature of their industry. However, hawala and exchange offices were reportedly spared during the raids. Some of the arrested were charged with “spreading rumours” about exchange rates and the devaluation of the Syrian pound. Meanwhile, the pound plummeted to its lowest value on record, sinking to 3,300 SYP/USD on the black market, as of writing.

‘Low’ and behold: The pound plummets again

Arrests of civilians on charges of using foreign currency are based on year-old legislative decrees that underscore the Syrian Government’s bid to invigilate and control the nation’s withering economy. In January 2020, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad issued decrees that imposed substantial punishments for the use of foreign currency in commercial transactions, and further penalised those caught “broadcasting or publishing fabricated facts, [or] false or fake allegations that cause national currency depreciation and instability” (see: Syria Update 27 January 2020). Since the decrees were issued, Military and Criminal Security have conducted numerous arrest campaigns targeting those dealing in foreign currency. Despite its protective measures, the Syrian pound continues to plummet. It has lost approximately 67 percent of its value in the past 12 months.

Recent measures affecting the Syrian pound have deepened fears among the civilian population over the state of the economy and the seemingly boundless deterioration of living conditions. These measures include the introduction of a 5,000 SYP banknote in February (see: Syria Update 1 February 2020); the introduction of a new, limited-use floating exchange rate; and the Central Bank of Syria’s inaction over the pound’s falls. In June 2019, as economic volatility was a growing concern, Central Bank Governor Hazel Qarfoul crushed any hopes for fiscal intervention when he stated that the Central Bank “follows a conservative [monetary] policy, and speaks [only] when there is a new policy or decision.” New policies have been few and far between, owing to the bank’s limited resources. In turn, Syrians have long assumed the worst about the currency’s future, a fear that has been compounded by the unprecedented inflation that has coincided with an increase in the cost of living. It is likely that the pound will continue to plummet, given widespread conflict destruction, sanctions, and a lack of foreign investment. Meanwhile, living conditions are expected to continue to decline and further arrests of civilians on charges of using foreign currency are likely.

IS Ambush Government Patrol in Rural Deir-ez-Zor

Al Mayadin, Deir-ez-Zor Governorate: On 10 February, media sources reported that Islamic State (IS) fighters had ambushed a Government of Syria convoy in Deir-ez-Zor, in the Al-Mayadin desert, killing at least 26 combatants. Seven of the dead were Syrian Arab Army soldiers. Reportedly, Liwa al-Quds militiamen and 11 IS fighters were also killed during the clash, which is said to have involved Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps members. The road connecting Damascus to Deir Ez-Zor is a vital transit route and commercial corridor within eastern Syria.

Deir-ez-Zor under attack

IS’s low-level guerilla insurgency is drawing increasing attention. Its persistence and the potential for attacks on a wider basis remain key concerns for the international community. Among the foremost questions around IS’s apparent reach is whether attacks in the Government-held Badia on the west bank of the Euphrates River could cross into SDF-held territory — a priority area for aid implementers looking to reach the neediest communities in northeast Syria. Within northeast Syria, the SDF has amplified a narrative that the Government of Syria is willing to harness IS as a cudgel against communities in the Kurdish-controlled enclave east of the Euphrates. Naturally, the SDF seeks to interpose itself as the strongest pillar of local defence, even in predominantly Arab communities on the east bank of the Euphrates in Deir-ez-Zor (see: Syria Update 8 February 2021). Needless to say, that the Syrian Government would (or even could) deliberately facilitate IS attacks in northeast Syria is a dubious proposition. The frequency and punishing impact of recent IS attacks targeting Government convoys evidences the potential for blowback. More realistically, former IS members, sympathisers, and potentially even new recruits have likely capitalised on weapons dumps or have linked up with sleeper cells to continue their guerrilla attacks. Such attacks can be expected to continue in all areas where the group had a firm territorial grip prior to the advance of Syrian Government and International Coalition campaigns in 2017.

Expansion of Russian Hmeimim Airbase

Hmeimim, Lattakia Governorate: On 8 February, media sources reported that new satellite imagery shows significant expansion at Russia’s Hmeimim airbase, near Jablah in Lattakia Governorate. The images indicated that a major runway was set to be extended by at least 1,000 feet (305 m) to accommodate larger aircraft. Relatedly, on 4 February, the Institute for the Study of War cited social media reports in a “low-confidence warning” that Belarusian forces would deploy to Syria in a “peacekeeping” capacity in September 2021.

Regional ambitions do not a strategy make

Moscow’s Syria strategy is more ambiguous and reactive than many analysts of the conflict realise. Among Russia’s objectives, only its interest in buttressing the Government of Syria is beyond debate. That said, the conflict has furnished Russia with clear strategic gains. These include opportunities to develop new military capacities, to test new tactics, and to demonstrate the weapons systems that are the backbone of the Russian arms industry. Access to the Mediterranean, from Hmeimim, is also a clear spoil of the Syria war. Whether Hmeimim’s longer runway will accommodate aircraft supporting operations in Syria — or elsewhere in the region — will be a key question going forward. The current expansion is clear-cut evidence that Russia seeks to hold the site as a forward military installation in perpetuity.

Local reports of potential Belarusian deployments to Syria are doubtful at best. Russia has leveraged regional partners and its own ethnic minority populations to advance its goals in Syria in the past. However, reports of Belarusian “peacekeeping” deployments to support Russian activity in Syria have previously arisen, and no such “peacekeepers” have materialised. If true, such a deployment would more likely reflect the eagerness of a growing Russian ally (Lukashenko’s Belarus) than any discernible objective of the Kremlin’s in Syria. There is little credible evidence to support the latest claims.

Turkey to Open Medical Faculty in Northern Syria

Ar-Ra’ee, Aleppo Governorate: On 6 February, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan issued a presidential decree opening a new medical faculty and an institute for health sciences in Ar-Ra’ee, northern Syria. The new faculty will be a branch of the University of Health Sciences in Istanbul (established in 2015). In parallel, the Free Aleppo University signed a memorandum of understanding with Mardin Artuklu University on December 31, allowing graduates of the former to pursue postgraduate studies at the latter, and establishing centres for Turkish-language education and YOS exams, an entrance requirement for foreign students at Turkish universities.

A boost for accredited higher education in northern Syria

The nonrecognition of higher education certificates has been one of the main challenges for medical students in northern Syria. Indeed, all of the area’s medical schools have, thus far, failed to obtain international recognition — these schools include those of the Free University of Aleppo (based in Mare’) and the University of Idleb. Turkish institutions are the favored choice for Syrian students who seek a recognised certificate. Previously, no Turkish universities with branches inside Syria offered medical degrees, although nursing qualifications were available. Establishing a branch of the University of Health Sciences in Ar-Ra’ee is a step toward improving the quality of medical education in northern Syria and increasing graduate’ access to job opportunities inside Syria and abroad (particularly in Turkey). Currently, holders of medical certificates from Government of Syria–run universities can undertake four years of specialised training through the Syrian Board of Medical Specialties (SBoMS), which allows them to work in their specialties inside Syria. However, it is not clear if the graduates of medical schools in opposition-controlled areas — such as al-Shamal Private University and al-Shahbaa Aleppo University — will have access to this training, given that denial of credentials is a key pressure tactic employed by Damascus to undermine areas outside its control.

Teachers Strike in Northwest Syria

Northwestern Syria: On 4 February, teachers from numerous schools across southern Idleb and western Aleppo announced a general strike to protest the suspension of financial support for the Syrian Interim Government (SIG) Free Directorate of Education and to demand long overdue salaries. The schools released a collective statement expressing the teachers’ dissatisfaction with the lack of support for education in northwest Syria, particularly in light of the deteriorating economic conditions. Many teachers in the region have reportedly not received salaries for more than two years.

School’s out

The muddy dynamics of the education sector in northwest Syria are largely a reflection of the region’s split governance and military landscape. Meeting the salary needs of educators has proven difficult for international donors, especially given that Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) controls large portions of the northwest. Although some of the striking schools are in HTS-controlled areas, interference by the HTS-affiliated Salvation Government has traditionally been limited to requiring permits for educational properties and (usually unsuccessful) attempts to influence the selection of teachers for courses on Islam. More challenging is the fact that teacher salaries in northwest Syria come from a variety of sources, including INGOs, the Government of Syria Ministry of Education, the Turkish Ministry of Education, and local NGOs. Although no schools in northwest Syria are managed exclusively by the Government of Syria Ministry of Education, in many schools, teachers continue to receive salaries from the Government of Syria. They work alongside teachers who draw salaries from the SIG Free Directorate of Education, which ultimately manages all schools. Schools with split funding streams for teacher salaries are most common in southern Idleb Governorate. In general, Government of Syria support for salaries is less common in areas in which HTS exercises greater influence.

Teachers have gone on strike over funding in the past. Such strikes have been seen as deft public broadsides to prompt international donors, such as UNICEF, to provide support. Risks to donors and NGOs stem from the potential public relations fallout of such events. Far more urgent is the need for students to continue receiving an education. A prolonged halt in education programming will have a significant impact on the development of a region that has already sustained significant blows to its infrastructure and human capital.

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below..

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

Syrian Who Fled to Germany 5 Years Ago Runs for Parliament

What Does it Say? Tareq Alaows, a refugee from Syria living in Germany, is running for a seat in the German parliament. He aims to fight for better rights for migrants and refugees.

Reading Between the Lines: His candidacy is seen by Syrians as a positive step toward attainment and inclusion in Europe.

Syria Faces Looming Crisis over Humanitarian Access

What Does it Say? During a UN Security Council session, Russia declared its intention to veto any extension of cross border humanitarian aid access to northwest Syria.

Reading Between the Lines: Russia and the Government of Syria have sought to isolate and weaken opposition areas, although analysts debate whether Russia will carry out its threat, given the refugee concerns of its partner, Turkey. Without aid, millions of civilians will suffer.

Syrian Oilfields No Longer a Priority for US Forces, Says Pentagon

What Does it Say? U.S. forces will no longer be openly protecting Syrian oilfields; rather, their focus will be on eliminating IS remnants.

Reading Between the Lines: The intentions of U.S. forces in Syria have been closely followed from Syria, where they are seen by some as a change of policy. While this possibility remains, the statements can also be seen as a mere backtracking from limited positions taken to appease the mercurial previous administration. Realistically, no change to U.S. policy on Syria can be inferred from public statements to date.

Iran-Syria Joint Chamber of Commerce Meets in Damascus

What Does it Say? The Iran-Syria Joint Chamber of Commerce convened on 8 February to discuss the Iranian Trade Center in Damascus.

Reading Between the Lines: Until the Iranian government improves its finances, direct business-to-business relationships through the private sector are likely to be the linchpin of bilateral economic cooperation.

What Does it Say? The piece calls for a greater EU engagement on Syria, including partner selection based on firm European principles, including the empowerment of women, human rights, inclusion, and democracy.

Reading Between the Lines: As the Syria ‘quagmire’ has persisted, the conflict has taken a back seat to other, more pressing issues in neighborhood affairs. The article is a reminder that in the absence of a robust military presence, the EU can exert influence over outcomes in Syria through aid and political actions.

Building a Better Path for Syrian Aid

What Does it Say? The piece argues that in the face of obstruction by Damascus and the Kremlin, donor agencies such as USAID must exercise a greater role in carrying forward aid delivery, particularly in northwest Syria.

Reading Between the Lines: The article clearly articulates the concerns of aid politicisation and the UN’s admitted shortcomings in Syria, yet its thumbnail sketch of independent aid delivery to Government-held areas leaves much to be desired.

What Does it Say? The article, penned by a respected researcher of IS, makes several points of note for the international response. Among them, it details how IS is able to persist in eastern Syria, and it calls attention to the potential social rift in the Self-Administration, not only on the part of marginalised Arabs in oil-rich Deir-ez-Zor, but also among the Kurdish fighters who are deployed to rural, Arab areas far from their home communities.

Reading Between the Lines: Such social tensions in particular will be a major factor in future stabilisation and resilience programming in northeast Syria.