On 24 February, Aleppo City Council announced that the remains of those buried in a park adjacent to Salah al-Din Mosque, in western Aleppo, will be relocated to the Modern Islamic Cemetery, east of Aleppo city, on 2 March, at the council’s expense. The Aleppo City Council called on those who have relatives buried in the park to report there no later than 8 a.m. on 2 March to ensure relocation. The council has threatened to move remains without notice, if families fail to meet the deadline. The precise motivation for the project is unclear, yet its potential importance is unambiguous, as it touches on one of the most sensitive social issues in Syria. Although the use of public spaces as makeshift burial sites is especially notable in Aleppo, this practice has been widespread throughout the Syria conflict, particularly in besieged and divided communities. As such, the incident highlights a major social question that has implications for conflict-sensitive aid implementation nationwide.

In Aleppo, the creation of makeshift graves came about as a result of the city’s besiegement between 2012 and 2016, when eastern and western neighborhoods were cut off from each other. Communities were forced to bury their dead in local parks and public gardens, or near mosques, as access to Aleppo’s large cemeteries was blocked and local cemeteries were at capacity. The process of relocating these makeshift gravesites started in early 2018, when the Government of Syria announced plans for Aleppo’s reconstruction. Shortly thereafter, the Aleppo City Council declared that bodies buried in makeshift graves in formerly opposition-controlled areas would be transferred to the Modern Islamic Cemetery to facilitate reconstruction and beautification.

However, issues surrounding the identification and documentation of bodies soon dominated the discourse. Since the Government of Syria reasserted control over Aleppo in late 2016, large proportions of those living in former opposition areas have been displaced or have relocated elsewhere, mostly to the opposition-held areas. Given that the many of those buried in makeshift gravesites are presumed to have had opposition linkages and the families of many others were displaced across conflict lines, the identification process is extremely fraught, as are myriad other concerns related to housing, documentation, and personal status for those who left the area. Forensic experts estimate that 90 percent of the bodies in such gravesites will remain unidentified; they will therefore likely be relocated without adequate documentation, and their families will likely be unable to locate them.

Aid actors, donors, and policymakers must note that this issue is relevant well beyond Aleppo. Since the outbreak of the uprising in 2011, public spaces have become highly contested in the struggle between the state and the opposition. The Government of Syria has reportedly targeted makeshift graveyards and cemeteries in recaptured areas, often defacing graves of particular significance and razing some sites entirely. Doing so achieves multiple objectives. First, it effaces the political identity of areas that witnessed displacement on a massive scale, such as eastern Aleppo and Darayya. One instance of this took place in May 2020, when media sources circulated satellite images showing the 4th Division razing Darayya’s Martyrs Cemetery, which contained 2,666 graves of individuals killed during the conflict. Second, eliminating these gravesites also obliterates evidence of possible war crimes — see, for instance, the transfer of the remains of a number of eastern Ghouta chemical attack victims in July 2018. Third, sabotaging graves can serve as retaliation against opposition figures or communities; this was evident, for example, in the disinterment and destruction of graves by Government forces following the recapture of Khan Elsobol, rural Idleb, in February 2020.

Social and cultural issues, alongside housing, land, and property (HLP) concerns, have been some of the most complicated dimensions of the Syria conflict. Such concerns are particularly acute where they intersect with the built environment, most notably in areas that witnessed large-scale physical destruction and long periods of opposition control. The importance of burial sites and other cultural heritage should not be underestimated. In addition to other major impediments to their return, many Syrians cite a growing sense of dissociation from their communities of origin. That the Government of Syria may weaponise burial sites to punish opposition communities, obliterate the memory of the opposition, and efface any traces of resistance should be among the foremost concerns of donor-funded projects focusing on rehabilitation in conflict-affected areas like western Aleppo.

Whole of Syria Review

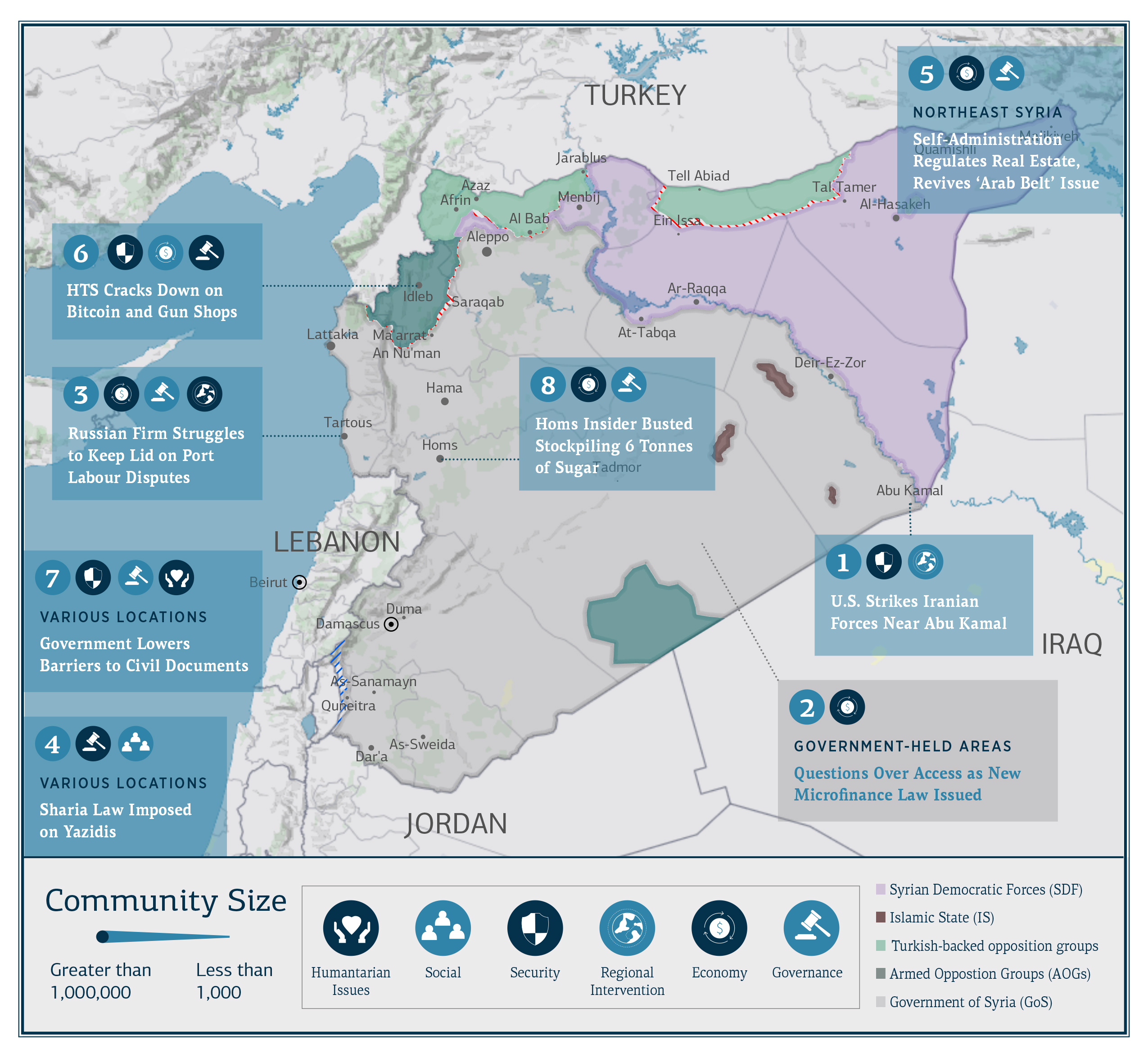

U.S. Strikes Iranian Forces Near Abu Kamal

Abu Kamal, Deir-ez-Zor Governorate: On 25 February, the U.S. Department of Defense announced that American aircraft had carried out an airstrike on border control points near the Syria-Iraq border, reportedly killing as many as 22 Iran-link combatants. The Pentagon stated that the attack had targeted Iraqi groups Kataib Hezbollah and Kataib Sayyid al-Shuhada, in retaliation for previous attacks targeting U.S. forces in Iraq — most notably, a 15 February attack on a U.S. base in Erbil.

Staying the course

The strike is the Biden administration’s first significant action concerning Syria. That said, the incident offers little insight into the administration’s approach to the country. Rather, the strike should be seen primarily as a landmark event in the course of tense ongoing negotiations with Iran over the latter’s regional presence and disputed nuclear program. Of note, Iran’s support for militia groups in Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon — viewed by the U.S. as inherently destabilising forces — was a key concern raised by critics of the Iran nuclear deal. The administration will find it difficult to overcome domestic political objections to achieving a new agreement or returning to the existing framework if it does not first demonstrate progress on the militia question. That the U.S. carried out the “retaliatory” attacks in Syria rather than on Iraqi soil indicates an aversion to further direct escalation in Iraq, where political rancour makes foreign intervention and outside influence issues of first-order significance. No noteworthy changes to the administration’s direction or priorities in Syria can be gleaned from the strike. However, further confrontation with Iranian forces and their regional affiliates is possible if tit-for-tat exchanges between U.S. forces and Iran-backed groups continue. Such incidents will grow more likely as talks between Tehran and Washington drag on.

Questions Over Access as New Microfinance Law Issued

Government-held areas: On 16 February, the Government of Syria issued Law No. 8 (2021), significantly altering the landscape for microfinance banks in Syria. Within Syria, the law has been portrayed primarily as a measure to facilitate loans for poor and low-income individuals. The law allows for the formation of microfinance lending institutions by foreign and local investors, whether individuals or institutions. Of note, it also raises the capitalisation requirement for microfinance banks from 250 million SYP; such banks now must be established with a minimum capitalisation of 5 billion SYP (3.98 million USD, at the official conversion rate used by financial institutions in the country). Central Bank of Syria Governor Hazem Qarfoul reportedly stated that the ceiling for loans will initially range from 15 to 30 million SYP (4,120 to 8,240 USD, at market rates). Qarfoul noted that changing economic conditions may require this limit to be adjusted in future.

Microloans with major problems

The law modifies Syria’s framework for microfinance, a system of economic support that is often seen as a linchpin of bottom-up local development. However, from the perspective of lenders, the law also limits the scope for such activities. The capitalisation threshold of $3.98 million set by Law No. 8 will be a barrier to entry for many. NGOs have previously provided microfinance in Syria, yet their access to the market must now be in doubt, given the high floor established by the law. Other programmes led by wealthy individuals and corporate and financial institutions can be expected to enter the field. Previously, perhaps the best known microfinance entity in Syria was Nour Microfinance, owned by Rami Makhlouf.

The law suffers from myriad other shortcomings. Local sources speculate that the bureaucratic wrangling involved in setting up microfinance institutions may mean that years pass before the first loans reach borrowers. Operational concerns are also apparent. NGOs typically provide technical assistance and capacity-building training as they work with individual borrowers, thus mitigating risk. Banks and private entities like those created under this law, on the other hand, seldom provide such support. Moreover, money is not a panacea. Labour, mobility and access, infrastructure and services (including electricity, water, and roads) are all necessary components for activities to succeed. Centralising microfinancing under the umbrella of the Central Bank of Syria, as this law seems to do, may also heighten the risk of close monitoring, interference, or politicisation by authorities. Besides, the beneficial impact of microfinance is itself disputed. These shortcomings aside, there is hope that the law will have some positive results. Needs are great, and microfinance may be an important vehicle for providing economic and social mobility. Of note, women may be among the clearest beneficiaries of such offerings, given that their access to conventional economic opportunities is often limited (see: The Business of Empowering Women).

Russian Firm Struggles to Keep Lid on Port Labour Disputes

Tartous city, Tartous Governorate: On 15 February, the Management Directorate of Tartous Port, which is controlled by Russian company Stroytransgaz (STG), announced the appointment of Gaysen Irat Raivatovic to the role of port director. Raivatovic succeeds Alexey Alexandrovich and will be the fourth director of the port since the Government of Syria leased its management to STG in 2019 (see: Syria Update 16-22 May 2019). The head of the Union of Maritime and Air Transport in Tartous, Fouad Harba, expressed reservations over Raivatovic’s appointment, noting that negotiations had been underway between the workers’ union and Alexandrovich, but talks would now “need to start again from zero.”

Fourth time’s the charm?

Russian investment has not fundamentally altered labour dynamics in Syria, although it has put the impotence of the Syrian Government on full display, as authorities have failed to safeguard the interests of Syrian workers. Two weeks after STG took over the management of the port, disputes ensued between the Russian company and Syrian workers over proposed changes to the workers’ contracts and salaries (see: Syria Update 24 February 2020). This conflict initially resulted in STG firing 3,600 workers — a drastic step which did prompt the Government of Syria to intercede, claiming that the decision violated the terms of the Russian-Syrian agreement over the port’s management. However, further disputes arose during 2020, including over the cutting of 2,600 workers’ salaries during the COVID-19 pandemic and over worker claims that the company had not provided adequate protective measures against the virus.

Elsewhere, worker complaints have also reportedly singled out SADA for Energy Services, a private company contracted to recruit workers and deliver salaries for STG-owned businesses in Syria — to include Tartous Port, Homs Fertiliser Factory, and the phosphate mines in Tadmor. SADA is managed by a close ally of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. Reportedly, it receives salaries from STG in U.S. dollars and pays workers at the Tartous Port in Syrian pounds at the official exchange rate, pocketing the difference. This situation demonstrates how Government-linked businesses are able to reap the benefits of their relationships with foreign companies, capitalising on the difference between official and black market exchange rates. Given that the disputes at Tartous Port have been ongoing for almost two years, it is unlikely that a new director will bring about a positive resolution in the foreseeable future — especially if workers continue to win little support from labour unions or the Government of Syria (see: The Syrian Economy at War Labor Pains Amid the Blurring of the Public and Private Sectors).

Sharia Law Imposed on Yazidis

Various locations: On 17 February, media sources reported that the Government of Syria Ministry of Justice had denied the Yazidi community’s application for its own religious courts to settle internal personal status matters. As a result, the community will be compelled to resolve such matters in mainstream courts that apply Sharia — Sunni Islamic law. Syria’s Yazidis are members of a religious minority that is often mischaracterised as a mere offshoot of Sunni Islam. They have denounced the decision, protesting against a state decree that essentially subsumes their faith under the Syrian state’s own interpretation of Sunni Islam. While the Yazidi faith shares many traditions and precepts with Sunni Islam, its syncretic belief system contains elements common to Christianity and Zoroastrianism, and its adherents have long sought protection through insularity.

No court of appeal for Syria’s disfavoured

The Government’s denial of the request accords with Damascus’s continuing efforts to control religious expression in Syria (see: Syria Update 14 December 2020). Although the Syrian Government has historically portrayed itself as a defender of minorities, taking a hard stand against Yazidis’ attempts at differentiation may be a way for the Government to quell criticisms leveled by alienated conservative Sunnis. Christians and Jews in Syria have separate courts to deal with personal status matters. By contrast, the Assad family’s own Alawite sect is governed by the same Sharia courts that preside over Sunni communities. Yet the comparison is a false one. Yazidi communities in Iraq and Syria have been subjected to historical victimisation that has been exacerbated by the conflict. While the Alawites dominate Syria’s political and security landscape, the Yazidis have long been persecuted. They were, for instance, deliberately targeted by the Islamic State (IS) over beliefs the latter viewed as heretical. Amid bloodshed and forced enslavement, IS also imposed its own, hardline Sharia law on Yazidis. The Government’s denial of this community’s request for a separate religious court does, therefore, prompt concern over the status of a group that has long borne the weight of oppression.

Self-Administration Regulates Real Estate, Revives ‘Arab Belt’ Issue

Northeast Syria: On January 28, the Self-Administration’s Social Justice Council issued a decree barring its legal bureaus (courts) from hearing cases concerning property and assets that exist outside official regulatory plans, in a move that may be related to historical Kurdish dispossession by the Syrian state. The measure prevents legal bureaus from adjudicating lawsuits related to the so-called “Amiri lands” — properties that are officially owned by the state, under a system dating to Ottoman times. According to this system, occupants may be granted land use and other rights, but not outright ownership. This system was reportedly critical to the relocation of Arab farmers to predominantly Kurdish areas in northeast Syria in the 1970s.

In parallel, the Executive Council of Jazira Canton issued a decree to re-evaluate the monthly rental prices of residential units in northeast Syria and categorise them into four tiers, according to the assessed quality:

- Tier 1: 10,000 to 50,000 SYP for low-quality housing.

- Tier 2: 50,000 to 75,000 SYP for medium-quality housing.

- Tier 3: 75,000 to 100,000 SYP for high-quality housing.

- Tier 4: 100,000 to 150,000 SYP for super-deluxe housing.

According to this decree, all rental contracts must be approved by and registered with the local municipality. Comins — local representatives of the Self-Administration — must observe all rental processes and carry out a mapping process for all rental units.

Real estate revanchism

While both of these decrees aim to regularise the real estate sector in northeast Syria, their objectives are widely divergent. The second decree responds to the depreciation of the Syrian pound, which is linked to price volatility in the housing market, a fraught concern in northeast Syria, as elsewhere throughout the country. The first decree, meanwhile, is more open to interpretation and could be seen as a political wedge in the hands of the Self-Administration. The decree may allow the Self-Administration to maintain the status quo for nominally public lands over which disputes have arisen. As Syria Report notes, it is possible that freezing the land could give the Self-Administration leverage over the Government of Syria in the future. It is especially notable that this issue is linked to the so-called “Arab Belt” — an area across northern Al-Hasakeh Governorate that encompasses lands granted to Arab peasants by the Government of Syria during the 1970s. That process was part of a development project and population transfer designed to undermine and dispossess the long-marginalised Kurdish population in the region. There are some who fear that the Self-Administration might implement measures to reverse this land transfer and other historic measures to manipulate demographics, including Law No. 7 (2020), which regulates the management of absentees’ properties. Indeed, it has been reported that Arab farmers in the region have preemptively sold properties, fearing potential confiscation or redistribution. Irrespective of the Self-Administration’s objectives, such fears are an unwelcome destabilising force in a region where social tensions are already palpable.

HTS Cracks Down on Bitcoin and Gun Shops

Idleb city, Idleb Governorate: On 23 February, social media and local sources indicated that Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) had cracked down on vendors specialising in the digital currency Bitcoin. The primary reason for the crackdown is reportedly Bitcoin’s use in transactions involving extortion, kidnapping, and other criminal activity. A few days before, on 21 February, local media reported that HTS had launched a campaign against unlicensed gun stores, raiding shops as well as the homes of those who had purchased guns in Jisr-Ash-Shugur, the Idleb city centre, and the village of Sahara. The arrests reportedly targeted former members of IS and Hurras al-Din, including French and Turkish nationals who had defected from both groups.

Blockchain blocked

Bitcoin is a volatile digital currency subject to sweeping price swings and speculation. However, given the Syrian pound’s downward trajectory, it’s not hard to imagine why Bitcoin might be gaining popularity in Idleb. Yet the recent crackdowns on Bitcoin and firearms are indicative, primarily, of another overarching dynamic: HTS’s long-running desire for tighter control over markets and rival actors. Kidnappers, foreign transplants, and rival groups in northern Syria have reverted to Bitcoin due to its relative convenience and the perceived anonymity of digital wallets. Cracking down on Bitcoin vendors in the region may impede its use, but strong incentives — and possible avenues — to use it remain. Currency instability is high, and there are no effective ways for local actors in Syria to restrict web-based digital transactions, even if they do succeed in blocking Bitcoin’s conversion to physical currencies locally. The use of cryptocurrencies is a matter of importance for the aid response, which has long explored digital payment platforms as a way to circumvent market instability, improve monitoring, and prevent diversion. Legal considerations are also relevant for those exploring digital currencies. On 18 February, the U.S. Office of Foreign Assets Control announced a settlement with a U.S. cryptocurrency provider over unspecified dealings in Syria. Notably, both the digital currency crackdown and the gun roundup come as HTS continues to bid for normalisation with the West. The group’s status has drawn increasing attention since its leader, Abu Muhammad al-Jolani, conducted a rare interview with an american journalist, Martin Smith, in Idleb.

Government Lowers Barriers to Civil Documents

Various Locations: On 22 February, the Syrian Government’s Ministry of Interior issued a decision that eases the issuance of civil documentation. According to the circular, civil documentation centres in all governorates are required to grant individuals any civil status documents — including ID cards, family booklets, and civil documents — regardless of whether there are charges outstanding against them. Media sources quoted one director in a civil affairs department, who stated that this protocol would hold for individuals facing charges for ambiguously phrased “court-related cases or specific crimes.” The precise interpretation of this phrasing is not immediately clear. Notably, this decision comes shortly after a decree issued by the Ministry of Interior required police departments in all governorates to simplify procedures related to the renewal of driver’s licenses. The decrees do not specify whether the security clearance requirements for obtaining civil documents have been scrapped.

It sounds good on paper, but …

At face value, both decisions appear to have significant benefits for the Syrian population, particularly those who reside in formerly opposition-held areas. Various assessments by the UN and others have found that the majority of Syrians in the country lack various types of civil documentation. Such documentation — including ID cards and birth, marriage, and property certificates — are an integral part of navigating Syria’s bureaucracy and accessing services. However, many Syrians find themselves caught in a bind: certain documents (for instance, a family booklet) are often required in order to obtain other documents. Without the first document, the applicant won’t be able to secure the others. Moreover, the issuance of civil documentation also requires security clearance from intelligence authorities. These barriers often leave Syrians without documentation and, as a consequence, access to healthcare, education, or other services.

That said, it is highly unlikely that these decrees will prompt the Syrian population at large to apply for missing documents, especially given the Ministry of Interior’s failure to specify which type of charges are encompassed in the waiver. The potentially wide latitude for interpretation leaves room for the possibility that individuals wanted on certain charges — such as terrorism — will still be caught up in the system. If this is the case, those who already avoid interaction with the Government out of fear of reprisal or detention will be locked out of benefits. The full extent and scope of the state’s plans for the new rules remain unclear, and it is possible that the scheme is merely intended to generate revenues from issuing such documents, particularly from applicants who apply from abroad at great cost.

Homs Insider Busted Stockpiling 6 Tonnes of Sugar

Homs city, Homs Governorate: On 18 February, media sources reported that six tonnes of purloined sugar had been found in the house of Ilham Kousa, a director of the Syrian Trade Corporation, in Homs. According to Director General of the Syrian Trade Institution Ahmed Najim, Kousa was referred to the authorities after the sugar bust. Najim later stated that “the maximum legal penalties will be taken against” Kousa and her associates for appropriating a subsidised basic foodstuff. Approximately 60 percent of Syrians are now food insecure, according to the WFP (see: Syria Update 22 February 2021).

Food insecurity continues

As food scarcity increases in Syria, the prices of all food, including subsidised products, continue to rise. Sugar is no exception, and local sources suggest that this sugar bust is indicative of a system in which privileged vendors and insiders buy bulk scarce commodities at subsidised rates and resell at considerably higher black market rates. It is highly likely that Kousa had planned to sell the sugar at inflated prices. Corruption and abuse of power are not unusual in Syria, yet the sugar incident became a focal point of social media outrage over collapsing material conditions. Syrians facing worsening food insecurity have portrayed the event as being emblematic of the market manipulations that line the pockets of Syria’s well-placed commercial entrepreneurs. The incident offers the Government an opportunity to demonstrate its willingness to combat corruption. But, as in other sectors, such good governance initiatives are likely superficial.

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below..

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

There Are Two Reasons the CBE Refrains From Raising the Price of Transfers

What Does it Say? The article argues that the Central Bank of Syria refuses to align the official remittance rate to that of the black market for two reasons: officials are afraid the black market rate will rise even further, and they stated that “the value of these transactions is low and does not warrant change.”

Reading Between the Lines: This reasoning is specious at best. Keeping the spread of rates high allows the state to skim more off the top to profit from arbitrage. Moreover, such remittances are a vital lifeline to average Syrians, even as their value is undercut by black market prices.

Robert Ford Opens up To the Syrian Observer

What Does it Say? In a long-form Q&A, former U.S. Ambassador to Syria Robet Ford discusses the prospect of the U.S. ceding ground allowing Russia and Turkey to achieve more of their objectives in exchange for taking on a greater role combatting IS.

Reading Between the Lines: Although they are not an expression of actual policy, Ford’s statements are an important signal of fatigue on the part of the Washington establishment concerning Syria, particularly as the conflict drags on with no end in sight.

Innocent Here and Guilty There: Two Different Views Concerning the Judiciary in Northern Syria

What Does it Say? The Interim Government and the Salvation Government have separate judicial courts in northern Syria. A person charged with a crime in one area is not necessarily charged for that crime in another, making passage across zones an ideal choice for people wanting to escape punishment.

Reading Between the Lines: Even though Turkey has substantial influence in northern Syria, there are wide gaps in the respective justice systems and other services.

Turkish Electricity to Northern Syria, a Dream Soured by Monopoly and Exploitation of Need

What Does it Say? People in Idleb either pay high prices for two hours of electricity per day through generators or must buy and install expensive solar panels. The article argues that a deal between Idleb and Turkey could mean cheaper electricity for all of Idleb.

Reading Between the Lines: While such a project could provide electricity and job opportunities, there is a prevailing fear that those in power will monopolise service provision and charge exorbitant prices for it.

The Banality of Authoritarian Control: Syria’s Ba’ath Party Marches On

What Does it Say? Although the Ba’ath Party’s political presence has been challenged and diminished over the last 10 years, it is still one of the Government’s most effective mechanisms, allowing it to retain its authoritarian grip.

Reading Between the Lines: The party’s gradual regaining of power has been one of the Government’s keys to survival, as social and political mobilisation are crucial instruments of the regime’s longevity.

Deir-ez-Zor Schools Strike To Protest SDF Decisions

What Does it Say? Teachers in Deir-ez-Zor have implemented a general strike against SDF policies, denouncing mandatory conscription for teachers and demanding to have their salaries pegged to the U.S. dollar.

Reading Between the Lines: Particularly in marginalised areas such as Deir-ez-Zor, the Self-Administration faces mounting criticism over its inability to root out corruption and improve services. Demanding more from residents in the form of military service will only aggravate these baseline concerns.

HTS Denies the News of Opening a Crossing From Saraqab Toward Regime-Held Areas

What Does it Say? HTS has denied that the Government of Syria opened a crossing from Saraqab to Government-controlled areas.

Reading Between the Lines: While the crossing may have been opened, sources reported that — as widely expected — no civilians were seen using it.

Talking To Russia: A Plan for Syria

What Does it Say? U.S. policy on Syria will change, likely taking a backseat to other regional priorities: policy on Iraq, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action with Iran, and partnerships with Arab Gulf states.

Reading Between the Lines: As the U.S.’s role persists and its attention drifts, it is likely that other actors — such as Russia and Turkey — will exploit the opening and become more deeply involved on the ground in Syria.

What Does the SDF Hope To Achieve By Dividing Deir-ez-Zzor Into 4 Cantons?

What Does it Say? The SDF has decided it will divide Deir-ez-Zor into four cantons, run by semi-independent administrations.

Reading Between the Lines: Administration of the southern, predominantly Arab areas has bedeviled the Self-Administration. Creating more localised authority in the area may respond to some criticisms, but it will not pave over existing inequities.