[dflip id="52319"][/dflip]Executive Summary

COVID-19 has forced already overburdened Syrians to confront accelerated price rises, severe goods and service shortages, and the further erosion of household resilience amidst an unprecedented economic downturn. Syrians may be well acquainted with such privations by now, but the confluence of conflict and COVID-19 has produced hardships greater than many have faced at any time in the past decade. Aid organisations and donor agencies have made efforts to sustain their support throughout the pandemic, but they, too, have been put under strain by the events of the past year. Exchange-rate volatility, fund-transfer impediments, access barriers, mobility restrictions, information gaps, and skyrocketing COVID-related needs have all complicated programme delivery, hampering the response at a time when needs are at their most acute. Undoubtedly, the ways in which international actors have navigated these challenges will be subject to long-term investigation and introspection. If any such evaluative process is to inform internationally funded responses to this and future public health emergencies in Syria, it must be framed by the experiences of health-crisis management evidenced by the current pandemic.

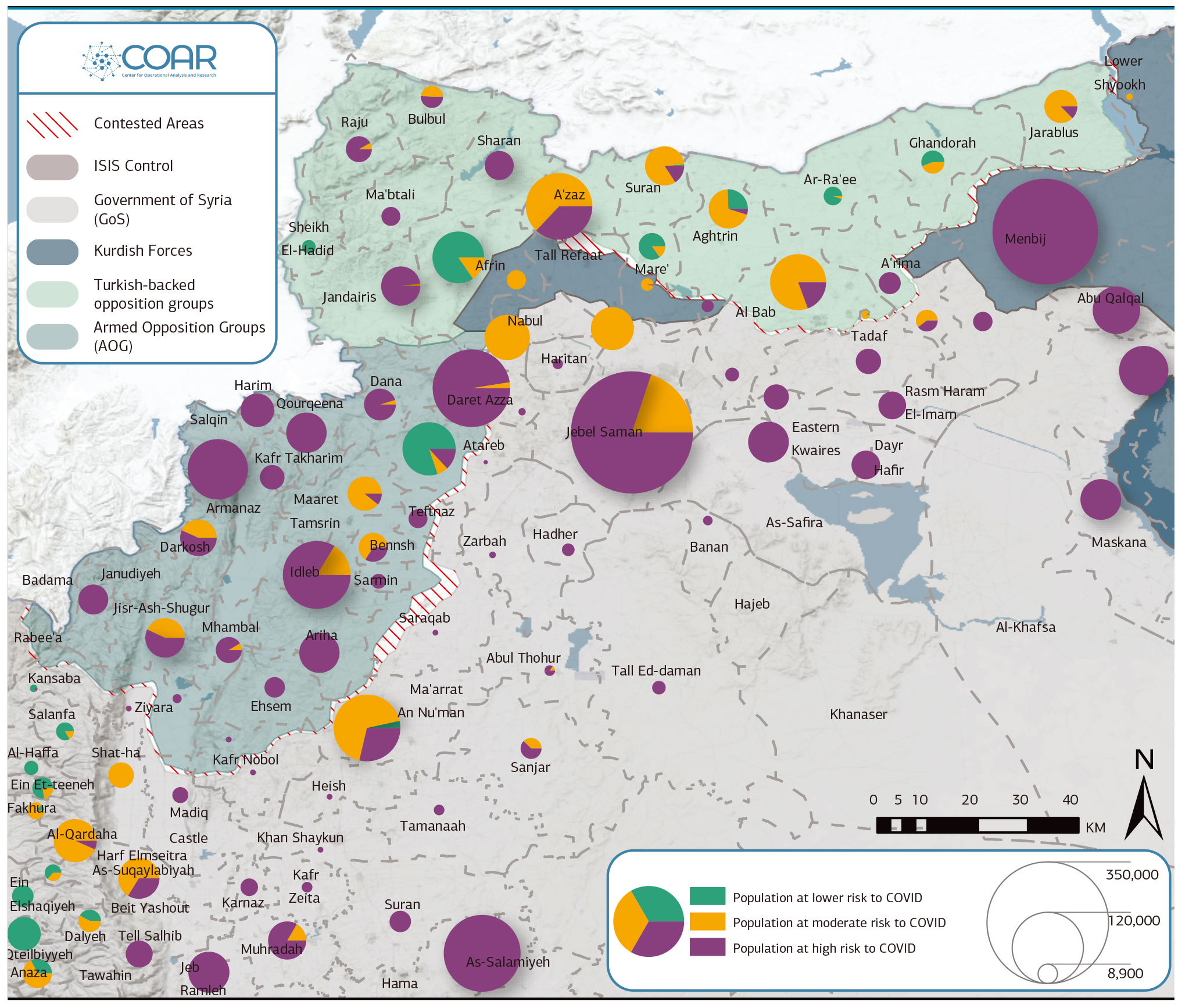

This paper contributes to that discussion.[1]COAR is grateful to two Syrian public health professionals, Drs Mohammed Darwish and Hazem Rihawi, for input in this report. Mohammed Darwish, MD, MPH, is a faculty associate at the Johns Hopkins … Continue reading Vaccine rollout remains a decidedly long-term proposition in Syria, meaning a comprehensive post-mortem assessment of public health and pandemic support measures is not yet feasible. However, it is possible to survey the events of the past year and take stock of lessons learned. As such, this report is an extensive assessment of Syria’s COVID responses to date. It takes specific note of governing actors’ emergency management strategies; the performance of primary and corollary health structures; aid interference and politicisation; and the interplay between public, private, and nongovernmental institutions. It provides a series of immediate and longer-term programming and policy considerations for aid and donor organisations working within Syrian pandemic response, health governance, and health-sector development. While this report is geared toward the highly technical needs of actors in such specialties, its discussion of the pandemic response strategies of various parties to the conflict lends insight into matters of interest for generalists, including Syria’s political economy, cross-line coordination, and the local community acceptance of governing authorities. Ultimately, it is hoped that these reflections will inform long-term decision-making and illuminate the systemic fragilities that will define Syria’s complex public health ecosystem long after the COVID-19 pandemic has ended. As such, this report assesses the Syrian pandemic response — both the actions of governing authorities and the performance of various aid response mechanisms — in each of Syria’s three regionalised health governance systems: Government of Syria–held central, southern, and coastal Syria; the northeast; and the northwest.

The Government of Syria’s COVID-19 response has been defined by securitisation, as it has curtailed the role of I/NGOs and the private sector. Meanwhile, concerns surrounding capacity limitations and the financial and political costs of imposing strict enforcement measures have prompted a laissez-faire attitude toward meaningful prevention measures. Securitisation is, nonetheless, reflected in the arrest of doctors, while testing remains heavily centralised and access tightly controlled. That said, service and capacity shortfalls abound, and alongside procedural and coordination issues, they are emblematic of existing programmatic entry points.

At the same time, Damascus has sought to undermine the northeast response, including by refusing to test the region’s samples; limiting cross-line health cooperation; and impeding data-sharing with regional authorities. As a result, northeast Syria is heavily reliant on support from INGOs and the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Yet not all of the region’s response shortcomings result from the intransigence of outside actors. Resource shortages are most acute in the northeast’s Arab-majority areas — where the response has been perhaps more lacking than anywhere in the country. Such disparities are a legacy of decades of state resource misallocation by Damascus, and they exemplify the entry points for donor-funded interventions which are apparent in the region. Despite such issues, the northeast Syria authorities have distinguished themselves by displaying the greatest ability to implement a centralised, non-pharmaceutical public health response in the country.

While the Government of Syria’s response has been characterised by the effects of over-centralisation, the opposite could be said of the response in the portions of northwest Syria where Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham exercises nominal control. The group has taken a backseat as I/NGOs have largely led the response. But too much decentralisation has undermined the basis for a coherent, unified set of policies. By contrast, Turkish authorities who influence other areas of northern Syria have heavily micromanaged the health response in areas held by the Syrian National Army, leaving a narrower space for I/NGOs. Measures to build local public health capacity, including through enhanced training and accreditation, emerge alongside coordination challenges as a key programming need in the region. On balance, northwest Syria represents the most transparent regional COVID-19 response in Syria.

BOX 1: Syria’s Fragmented Health SystemBefore the conflict, the Ministry of Health (MoH) was the foremost health authority in Syria. It oversaw nationwide governorate-level health directorates, which in turn regulated the operation of public and private health infrastructure in partnership with the private sector, local organisations, and specialist MoH commissions. Still in place in Government-held areas, this model has since undergone extensive change, owing to a combination of territorial fragmentation, conflict-related damage and dysfunction, and severe resource shortfalls. Alternate providers have subsequently moved into gaps created by the ad hoc reorganisation of public healthcare at an increased rate nationwide, with private and nongovernmental services now comprising increasingly large proportions of Syrian health services in all areas. The manner in which alternate providers have compensated for change in the national public health sector can vary significantly depending on the disposition of the local governing authority, aid access conditions, and the particular shortcomings of locally available services. In northwest Syria, public health services are administered by two unevenly resourced and variously cooperative governing authorities: the Salvation Government (SG) and the Syrian Interim Government (SIG). The range of entities linked to these two actors further complicates regional health governance, with the SG allowing the nominally independent health directorates of Idleb and Aleppo to undertake the bulk of healthcare management in areas under its control, and several Turkish health directorates serving areas where Turkish-backed armed groups buttress the SIG. Services provided by both parties are weak, however, and are supplemented (and often eclipsed) by the WHO-led Health Cluster cross-border operation, UN agencies, and Syrian and international NGOs. The healthcare system in northeast Syria operates under the general leadership of the Health and Environment Authority (HEA) of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES — commonly referred to by COAR as the Self-Administration). Unsurprisingly, the system encompasses multiple layers of institutional bureaucracies and power centres that mirror the Self-Administration’s governing philosophy, extending from the central authority at the political centre, down to district-level health committees. Private and nongovernmental services have similarly played an expanded role in the northeast, while the Government of Syria’s MoH retains a (limited and often ambiguous) role in the joint administration and management of health services in the region’s Government-held enclaves. |

Government-Controlled Syria

Roughly one year into the pandemic, the Syrian Government has largely implemented half measures in response to COVID-19, proclaiming its adherence to the letter of certain WHO recommendations but failing to enact them in spirit. Enforcement of the most rudimentary precautionary and prevention policies has been limited, and social and economic pressures have prompted authorities to abandon a short-lived experiment with stringent lockdowns in favour of a largely business-as-usual approach. Such inconsistencies have inevitably produced haphazard public compliance, while limited Government initiatives ring hollow to a population struggling to meet its most basic needs in Syria’s crumbling economy. The result has been enduring concern over the scale and scope of the pandemic’s reach in Government-controlled areas, the reality of which has been exacerbated by dubious state commitment to transparency and nondiscrimination, poor regulation and management, and broadly inadequate, inaccessible, and unaffordable support across the public, private, and nongovernmental health sectors.

For actors in the humanitarian and development space, improved public health outcomes can be supported through programming interventions that address the region’s abundant shortfalls in capacity, training and preparedness, and interagency coordination. While concerns over aid politicisation are perhaps more acute in Government-held areas than anywhere else in Syria, entry points exist with a range of associated risks. For donor agencies and implementers, factors such as risk tolerance, mandate, and red lines will naturally inform the parameters of debate over entry points to public health in Syria.

Recommendations

- Support the revision of public health education, with a focus on epidemiological training.

- Provide clarity around, and expand, humanitarian exemptions to restrictive measures, which have yet to mitigate the impact of complex compliance requirements.

- Advocate for the decentralisation and expansion of equitable testing regimes, to include the private sector, in addition to the decentralisation of monitoring and resource distribution.

- Enhance emergency health capacity by bolstering the Early Warning and Response System (EWARS).[2]Since its establishment in 2012, the joint WHO-MoH Early Warning and Response System (EWARS) has generally failed to detect disease outbreaks. It has often been late in reporting cases, in addition … Continue reading Recommend the inclusion of private-sector and governorate-level stakeholders at more systematic EWARS committee meetings, including WHO delegates.[3]During the pandemic, EWARS committee coordination meetings have not been regularly conducted. Related quality-assurance committees have also failed to conduct sufficiently frequent healthcare … Continue reading

- Work to improve harmonisation of EWARS with other domestic and international emergency monitoring and tracking systems, especially the Early Warning and Response Network (EWARN).

- Audit the response capacity of medical facilities through a joint MoH-WHO committee, undertaken in coordination with Syrian Arab Red Crescent (SARC) and other providers.

- Consider the subsidisation of private primary healthcare entities in emergencies to offset high treatment costs and limited public-sector health access, while remaining sensitive to the risks inherent to local partnership, particularly with private entities.

- While donor red lines and aid agency mandates may impede such an approach for some actors, support for the heightened involvement of Ministry of Higher Education hospitals in emergency response conditions may be critical to closing extant gaps.

- Fund healthcare worker positions with local NGOs in underserved areas, where feasible in accordance with necessary conflict-sensitivity safeguards. Salaries should be commensurate with peers at INGOs and UN agencies.

- Perhaps the most sensitive issue to emerge as a gap concerns SARC’s coverage in rural areas and its capacity as a hospitalisation service provider. While such support may be among the most impactful means of bridging existing gaps, any such gains must be weighed against the potential for instrumentalisation of support.[4]SARC operates in parallel to government public and emergency health services. Regarded as a competitor, any expansion of SARC services may invite co-option. Strong monitoring procedures must be … Continue reading

Crisis and Authority

COAR, among other observers, anticipated that state authorities might instrumentalise COVID-19 in service of imposing further restrictions on former opposition-held communities. The state has seldom missed the opportunity to impose itself where it believes there are grounds for the suppression of countervailing forces. Additionally, the Syrian Government has frequently downplayed or denied disease outbreaks in politically adversarial areas throughout the conflict, frequently going so far as to manufacture grounds for delayed or discriminatory emergency resource distribution, limit the involvement of non–public sector health actors, and marginalise the international response. This was the case in the Government’s initial denial of the 2009 cholera outbreak, and its denial of the extent of later polio and cholera epidemics, in 2013 and 2015, respectively. Most notably, the Government’s failure to support the immunisation of Deir-ez-Zor children as part of a WHO/UNICEF 2012 vaccination drive has been strongly linked to the emergence of polio in that region the following year. (Deeper examination of the history of pandemics in Syria can be found in this annex: Public Health Responses to Syria’s Past Epidemics)

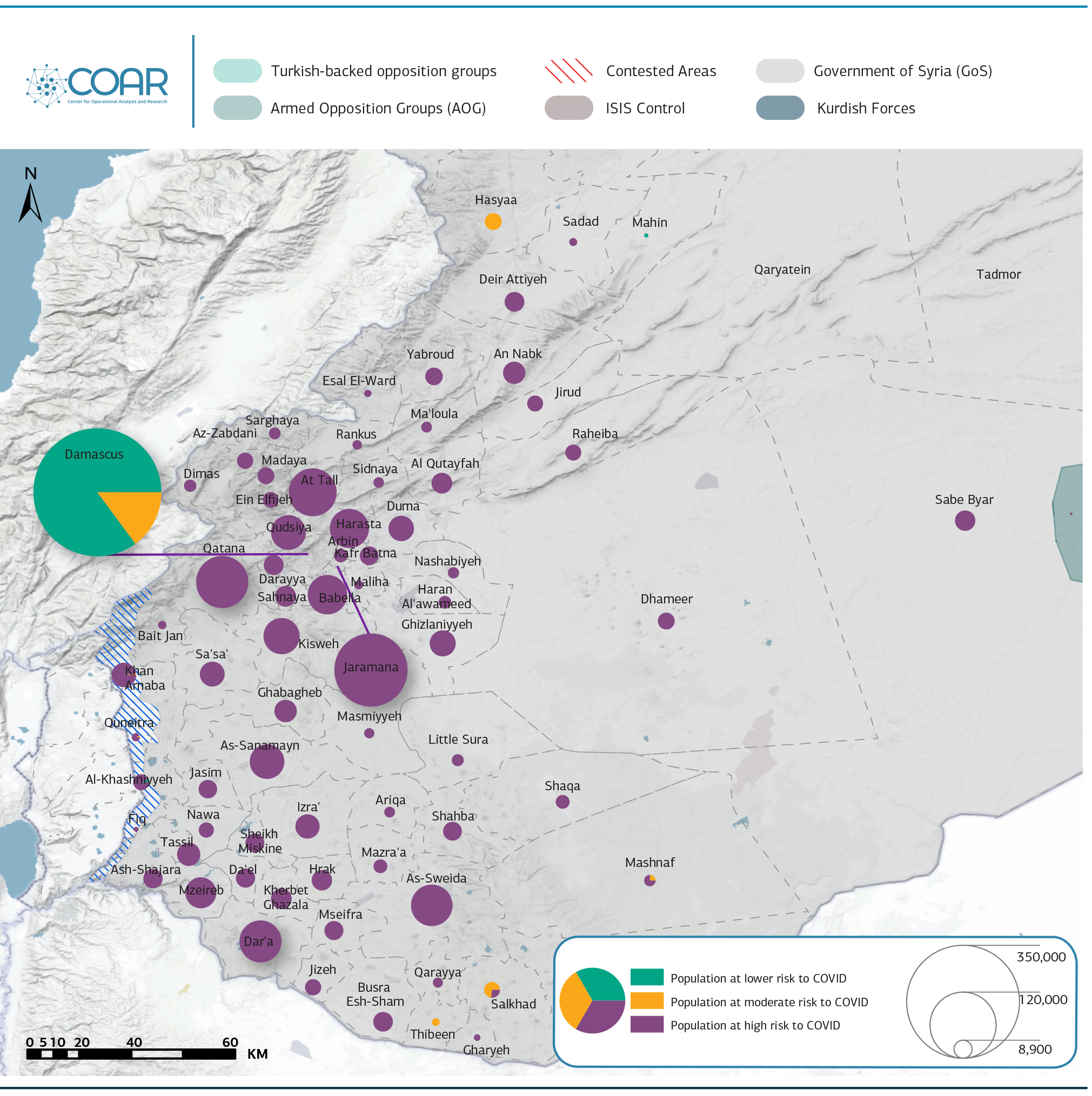

Ultimately, however, the concern that less compliant Government-held communities would be subject to selective crackdowns has not materialised to the extent many feared.[5]Arrests and supply restrictions were reported in reconciled areas early on, but these events were not especially frequent and have not noticeably increased in subsequent months. Instead, they have been neglected, much as they were in pre-COVID times.[6]For example, many healthcare workers from reconciled areas have not been reinstated, despite the current pressures faced by the medical system. This is a continuation of Government policy in these … Continue reading Local populations, services, and charities that might support the response in reconciled areas remain shackled by overbearing security and political bureaucracies. International partners have similarly been subject to restrictive registration, access, funding, and project-approval procedures in reconciled areas,[7]“Blacklisted” beneficiaries have also been removed from aid distribution lists. See: Physicians for Human Rights, “Obstruction and Denial: Health System Disparities and COVID-19 in Dar’a, … Continue reading causing some expert sources to estimate the amount of support provided to such communities may be as much as three times less than that provided to more loyalist areas.

In one sense, this suggests that the Syrian Government is broadly content with state security control in such areas and has little interest in using COVID-19 as a pretext for further punitive action. More interestingly, it points to the economic, social, and practical realities that have moderated Government behaviour throughout the pandemic. It can be surmised that central authorities fear that the application of extraordinary measures would not demonstrate state control, but rather act as an admission of state fragility. Indeed, to impose tight restrictions in aggrieved communities experiencing extreme hardship is to invite potentially destabilising noncompliance, which the Government can ill afford.

A tepid pandemic response is therefore a natural approach in reconciled areas, yet the state’s current problems of governance and authority are such that its leadership has been equally noncommittal in Government-controlled areas as a whole. In order to negotiate the delicate balance between public health, the national economy, and reconstruction, robust pandemic response actions by the state in Government-controlled areas have given way to carefully orchestrated public diplomacy, a constrained COVID-19 response environment, and what one commentator has aptly described as a “desultory experiment with herd immunity.”[8]Asser Khattab, “It’s like Judgment Day: Syrians recount horror of an underreported COVID-19 outbreak,” Newlines Magazine, 11 October 2020.

Securitisation and Politics of Denial

A range of mainly security-led methods have been deployed to navigate this rocky terrain, dictate the emergency narrative, and uphold the semblance of state control. Medical professionals warning of the emerging risk to public health were reportedly threatened or arrested early on, while intelligence services were quick to establish a presence in hospitals to monitor their activities.[9]Mariya Petkova, “Concern mounts over catastrophic coronavirus outbreak in Syria,” Al Jazeera, 16 March 2020. Note that monitoring by the Mukhabarat reportedly continues to this day. Public, … Continue reading Government officials long insisted that Syria was COVID-free, despite mounting evidence to the contrary, and did little to mobilise interagency coordination to develop a more comprehensive preparatory response. Most tellingly, the Syrian Government’s EWARS issued no meaningful reports on COVID-19 until after public officials formally admitted the first case in late March.

Government reticence to publicly acknowledge the onset of COVID-19 derives from a health emergency playbook that has long deployed ambiguity, mistruth, and obstruction in order to shield the state from accountability. The parallels with prior wartime outbreaks of cholera, polio, and leishmaniasis will be obvious to many familiar with recent Syrian public health crises, as will the ongoing mismatch between reports of events on the ground and official disclosures. COVID-19 case numbers released by the Government reflect neither rising bed occupancy nor the creeping national death rate, pointing instead to a more politically palatable version of events that is both a willful fiction and an indictment of the Government’s capacity for pandemic response. Daily case numbers in Government-held areas have shown a peculiar consistency, but the authorities have yet to acknowledge that — as is widely believed — their figures merely reveal the capacity of available testing rather than anything approaching the actual infection rate. One September 2020 study estimates that just 1.25 percent of COVID-19 deaths were being reported in Damascus. [10]Imperial College London, “Estimating under-ascertainment of COVID-19 mortality: An analysis of novel data sources to provide insight into COVID-19 dynamics in Damascus, Syria,” 15 September 2020.At best, such underreporting indicates scant interest in extending surveillance systems to support a more comprehensive response. At worst, it displays a conscious effort to downplay reality and manage the crisis in a way that has prompted concern about an eventual domestic vaccine rollout.[11]Human Rights Watch, “Syria: COVID vaccine access should be expanded, fair,” 2 February 2021.

Advocacy groups have called for greater transparency,[12]Amnesty International, “Syria: Lack of adequate of COVID-19 response puts thousands of lives at risk,” 12 November 2020. but robust, well-coordinated, and transparent COVID-19 crisis management represents a critical threat to the Government, and greater cooperation is therefore unlikely. When an executive response plan was agreed by the Cabinet, it largely kept response measures in-house, excluding private, nongovernmental, and international stakeholders throughout the spring and restricting their involvement thereafter.[13]For instance, private hospitals were prohibited from receiving suspected COVID-19 cases until July 2020.International and national NGOs currently face extensive restrictions for health-related programming, the WHO has been prevented from supplying testing kits to private and nongovernmental partners in Government-held areas, and the state remains reluctant to share data on its resources and capacity. Even as the pandemic appears to have worsened over winter, official announcements maintain that Syria is faring better than all other countries in the Middle East.[14]Heba Mohamed, “COVID-19 Amidst Syria’s Conflict: Neglect and Suppression,” Physicians for Human Rights, 13 January 2021. Of all the measures taken by the Government since the outbreak of the pandemic, it may be that its efforts to stage-manage the pandemic’s impact on its own survivability are the most comprehensive.

MoH Management

Health-response capacity in Government-held areas is spread across public, private, and nongovernmental sectors, but is unevenly distributed. This is the result not only of resource misallocation and decrepit health infrastructure but of management failures that have exacerbated differences in service quality and accessibility throughout the pandemic. At the policy level, these differences begin at the very top. Local sources explain that the MoH is frequently frustrated by the Council of Ministers in its effort to secure Government support for the mandatory enforcement of even basic preventative measures in public spaces and hospital settings, and cite accusations that the WHO is too closely tied to Damascus to leverage a more wide-ranging response.[15]Accusations against the WHO include partnering with organisations previously under the control of President Bashar al-Assad’s tycoon cousin Rami Makhlouf; remaining silent over allegations that the … Continue reading The WHO is, of course, grappling with complex moral and practical questions that are beyond detailed debate here. However, such reports echo earlier discussion regarding the extent to which the defence of central state integrity trumps even the most commonsense measures in the Government’s pandemic response architecture.

MoH public hospitals were the backbone of Syria’s health system pre-war, but the combined impact of wartime destruction, healthcare worker displacement, poor working conditions, and severe budgetary shortfalls means that alternative providers have increasingly compensated for ailing public services in Government-controlled areas. Little has been done to reverse this trend in order to ensure healthcare access during the pandemic. Preferential treatment for those with cash or “wasta” (influential connections) is reportedly common.[16]According to one local source, this extends to the exclusive reservation of unused critical care beds, private rooms, and ventilators for security services and Ba’ath Party members, those connected … Continue reading Rural communities have been isolated, and images of chaotic COVID-19 clinics have prompted most Syrians to care for themselves at home. Meanwhile, medics at public hospitals operate under lax distancing and preventative measures; quality assurance structures are weak; and a lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) is thought to have resulted in a troubling number of healthcare worker deaths. With public hospitals viewed less as treatment centres and more as potential sites of transmission, markets for oxygen tanks and other supplies have boomed,[17]Pre-COVID, the price of an oxygen tank was around 40,000-45,000 SYP (14-16 USD). Today, the price has risen to 225,000-300,000 SYP (78-90 USD) — almost double the average current monthly salary. social stigma around the virus has endured, and the scale of the public health challenge is hidden largely behind closed doors.

BOX 2: Two Sides of the Syrian Arab Red Crescent (SARC)SARC remains the most trusted and efficient primary healthcare provider in Government-controlled areas. SARC discriminates less in patient admission than public and private hospitals, and patients generally are able to walk in without referrals to receive treatment. SARC provides a generally higher quality of care than both private and public hospitals, in addition to enforcing greater precautionary separation and isolation measures. It has a good centralised reporting system and monitoring and quality assurance structures. However, SARC has been afforded a restricted capacity within the COVID-19 response and has been primarily relegated to the provision of primary care. SARC officials reportedly complain of ventilators and medical supplies being withheld by the Syrian Government. Sources claim that SARC is treated by the Government as a quasi–private sector actor; the organisation is reportedly viewed by some MoH officials as a competitor, seeking to establish a parallel healthcare system. Nonetheless, despite nominally being a charity that receives donated medicines from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), SARC charges high fees for the admission and treatment of COVID-19 patients.[18]Similar to private hospitals, SARC charges a sum of 100,000 SYP for first-day admission of COVID-19 patients, and up to 50,000 SYP for each subsequent day. SARC ambulances regularly charge “unofficial” fees, and the destination of patients is often based on preferential arrangements with specific hospitals. SARC has also been accused of not redistributing donations intended for other nonprofit organisations, hoarding medicines and passing them on only after their expiry. While SARC is relatively well-established in rural areas relative to other healthcare providers, SARC facilities do not provide the same level of services in former opposition-held communities. Nonetheless, SARC remains arguably the best access point for the response within Government-held areas, and its role in hospitalisation may be critical, if it is to expand beyond its main, limited function as a primary healthcare provider. |

Underregulation of Private Healthcare

Despite obvious and mounting problems with public healthcare access, the MoH prevented private hospitals from receiving suspected COVID-19 cases until July 2020. Even now, many private hospitals in Government-controlled areas refuse to admit COVID-19 patients, and the cost of treatment in those that do is prohibitively high for the average Syrian.[19]Local sources report that a night at a private hospital in a provincial centre may cost up to 150,000 SYP (approx. 70 USD). Like more advanced treatment in public facilities, admission to private emergency care is also reportedly discriminatory and often requires a referral from a doctor working in both the public and private domains. While this practice may relieve some pressure, the underregulated, profit-driven incentives with which it is entwined weaken the utility of private services in pandemic response. Indeed, doctors reportedly shop around for commissions on COVID-19 referrals, suggesting that patient needs are a lesser factor.

More worryingly, COVID-19 patients are reportedly seen as a barrier to “higher value” caseloads, leading private hospitals to prioritise the rapid discharge of such patients in favour of clearing bed space for more profitable cases. It is therefore unsurprising that a September 2020 MoH decree requiring the suspension of non-emergency surgeries has been broadly ignored by private hospitals, many of which are thought to have circumvented this restriction by arbitrarily making more severe diagnoses. Limited MoH monitoring of private facilities has enabled this practice; it is also a chief reason why private outpatient clinics have continued in spite of the MoH directive, why adherence to precautionary measures in private medical settings is irregular, and why some (especially nursing) staff practice without the requisite qualifications.

BOX 3: Private COVID-19 Testing and Service ExploitationSince August 2020, the Government of Syria has allocated 19 private laboratories to provide PCR testing for outbound travellers who can provide proof of travel. The cost of a test has been set at 127,000 SYP (approx. $37), though there are reports of customers receiving same-day results by paying more than three times that amount. The MoH itself has seemed to recognise the emergence of new avenues of exploitation, declaring in August that some MoH workers were extorting citizens seeking PCR tests.[20]Nour al-Deen Ramadan, Ali Darwish, and Zeinab Masri, “Coronavirus opens new door to corruption in Syria,” Enab Baladi, 11 September 2020. Local sources have also noted the spread of a phenomenon whereby COVID-positive individuals who wish to travel have been able to bribe testing laboratories to test others under their own name in order to receive a negative diagnosis. |

Material Resources: Shortfalls, Sanctions, and Politicisation

COVID-related resource shortfalls are not unique to Syria, but they are notable in Government-controlled areas both for their reported severity and the manner in which they have been politicised throughout the pandemic. Evidently, many problems in the former category are compounded by the damage to public health and supporting infrastructure, the continuation of conflict, economic adversity, and a rate of infection suspected to far exceed official figures. Ventilators in Government-controlled areas are found largely in private hospitals,[21]As an example, more than three quarters of the 110 ventilators in Damascus city are located in private hospitals. as public facilities eschew the cost of such expensive equipment in favour of more utilitarian supplies.[22]Non-emergency supplies and equipment have become more expensive, owing to domestic production-cost increases and import restrictions. This has placed additional pressure on public hospital budgets. Public facilities are therefore among the most chronically underequipped in the fight against COVID-19 — even in terms of providing the most basic PPE for healthcare workers.

The Syrian Government has been vocal in insisting that necessary medical supplies and support services have been impeded by sanctions.[23]“Syria: Local Currency Devaluation Exacerbates Sufferings In Damascus,” Asharq Al-Awsat, 16 May 2020. In many respects, this is a valid complaint. There is evidence that restrictive measures imposed by both the U.S. and the EU have prevented the provision of PPE and technical support and training to health authorities working at the forefront of the response. A recent European Commission Guidance Note on Syria thus provides welcome clarification on the interplay of sanctions and rights-based humanitarian action, explaining that the provision of humanitarian support “should not be prevented by EU restrictive measures.”[24]European Commission, “Commission Guidance Note on the Provision of Humanitarian Aid to Fight the COVID-19 Pandemic in Certain Environments Subject to EU Restrictive Measures,” 16 November 2020. Certain exceptions to this commitment nevertheless apply; the local partner approval process remains an arduous one, subject to individual member state discretion; and U.S. sanctions — much broader in scope — offer much less in the way of subtlety. Grantees confront ongoing delays in navigating the sanctions bureaucracy, run the constant risk of violating grant requirements, and may be forced to curtail their activities.

Sanctions cannot wholly be blamed, however. Sources within the MoH claim that the Syrian Government has received up to an estimated 120,000 testing kits and other supplies from a range of countries,[25]This includes five shipments of 10,000 testing kits from China, in addition to a number of ventilators; two shipments of 10,000 kits and a number of ventilators from Russia; and shipments from Iran, … Continue reading yet has preferred to sell many of these units to private testing laboratories rather than distribute them in the public health system. There are also allegations that the Syrian Government has seized supplies destined for opposition-held areas for similar purposes and has endeavoured to ensure that most PCR machines provided by the WHO are delivered to Government-controlled areas. Such behaviour is to be expected — given the Government’s past attempts to politicise aid distribution and divert resources — and underlines the challenge of charting a course towards equitable emergency response.

Human Resources

Public institutions, including universities, primary healthcare centres, and hospitals, remain the main centres for the education and development of new medical professionals in Government-held areas. These institutions do not offer uniform access to all specialties, however, and sanctions inhibit international support for the development of future professionals via the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Higher Education. Means of addressing this long-term issue will need to be explored, especially because recent years have seen far greater international investment in direct healthcare delivery than in career development and training.

Northeast Syria

Prior to the Syrian conflict, the northeast was considered the most generally underserved region of Syria; it suffered from weak investment in, among other things, health, water, and sanitation infrastructure. The destruction visited on the region during the conflict has only exacerbated these pre-existing vulnerabilities, particularly in Arab-majority communities where greater involvement in the armed opposition and the fight against Islamic State have caused more pronounced damage to health services and infrastructure. Of course, neglect and destruction are not the only causes of the ongoing ravages of COVID-19 in the region. Equally important are the political rivalries and governance shortfalls that dictate the capacity of the Self-Administration in general, as well as the northeast pandemic response environment. Indeed, it is largely matters of governance, power, and authority that explain why the Self-Administration’s Health and Environment Authority (HEA) has struggled to promote a consistent region-wide pandemic response. It is these factors that have stymied the implementation of even the simplest preventative measures and means of coordinating with local, national, and international stakeholders.

That said, many of the factors shaping the response environment are beyond the immediate control of the Self-Administration and other supporting actors — severe problems of emergency cross-line and cross-border supply and logistics foremost among them. Other factors, such as a weaker response in Arab-majority areas, partly result from the wartime imperatives of an unsteady Kurdish-dominated polity, self-imposed political priorities, and questionable local legitimacy and community acceptance. Regardless of their origin, the barriers to pandemic response in the northeast demand attention by international actors precisely because these actors are the crutch upon which the region has relied throughout the current pandemic. Given that this reliance will likely persist for the foreseeable future, the longer-term resilience of regional health services to future emergencies is largely a function of the Self-Administration’s ability to harness partnerships — and the willingness of its partners to recognise and pursue sustainable service-development opportunities.

Recommendations

- Continue to explore alternatives to cross-line supply operations, in particular via the Kurdistan Region of Iraq.

- Strengthen coordination between the HEA and the Health Working Group, and among members of the Health Working Group.

- Remain mindful of political and social concerns that limit the willingness of healthcare workers and other actors from working closing with entities affiliated with the Self-Administration.

- Improve coordination between domestic health emergency monitoring systems in the northeast and elsewhere. EWARN already has a relatively well-developed presence in the northeast, and the greater harmonisation of the EWARS system with HEA mechanisms would be beneficial.

- Invest in regional vaccination and malnutrition-tracking programmes; the dearth and low capacity of such programmes is an issue that predates COVID-19 and creates local popular resentment that impedes social cohesion.

- Encourage capacity development for Rapid Response Teams (RRT), especially in underserved communities in Ar-Raqqa and Deir-ez-Zor.

- Support human resource development to buttress public health emergency response in underserved areas, including training support for ICU management, specialist equipment, and Infection Prevention and Control (IPC).

- Contribute to the advanced professional development of existing staff through a combination of “train the trainer” programming; collaboration between local and international universities and other institutes; and the engagement of other public-health stakeholders, including the private sector and I/NGOs.

- Develop and unify regulatory enforcement in partnership with regional health authorities and other stakeholders.

- Modernise and unify health information systems, including by introducing electronic support for medical protocols.

Leadership and Authority

Of all the health authorities in Syria, the HEA of the Self-Administration has been most plausible in its attempts to minimise community transmission. It was the first to institute partial lockdown measures region-wide, going so far as to close cross-line routes between the Self-Administration and areas under the control of the Syrian government and Turkish-backed groups in early March 2020. Restrictions were broadly relaxed in the summer, but the intervening period has seen the imposition of targeted temporary lockdowns and other measures, in an apparent effort to slow the infection rate.

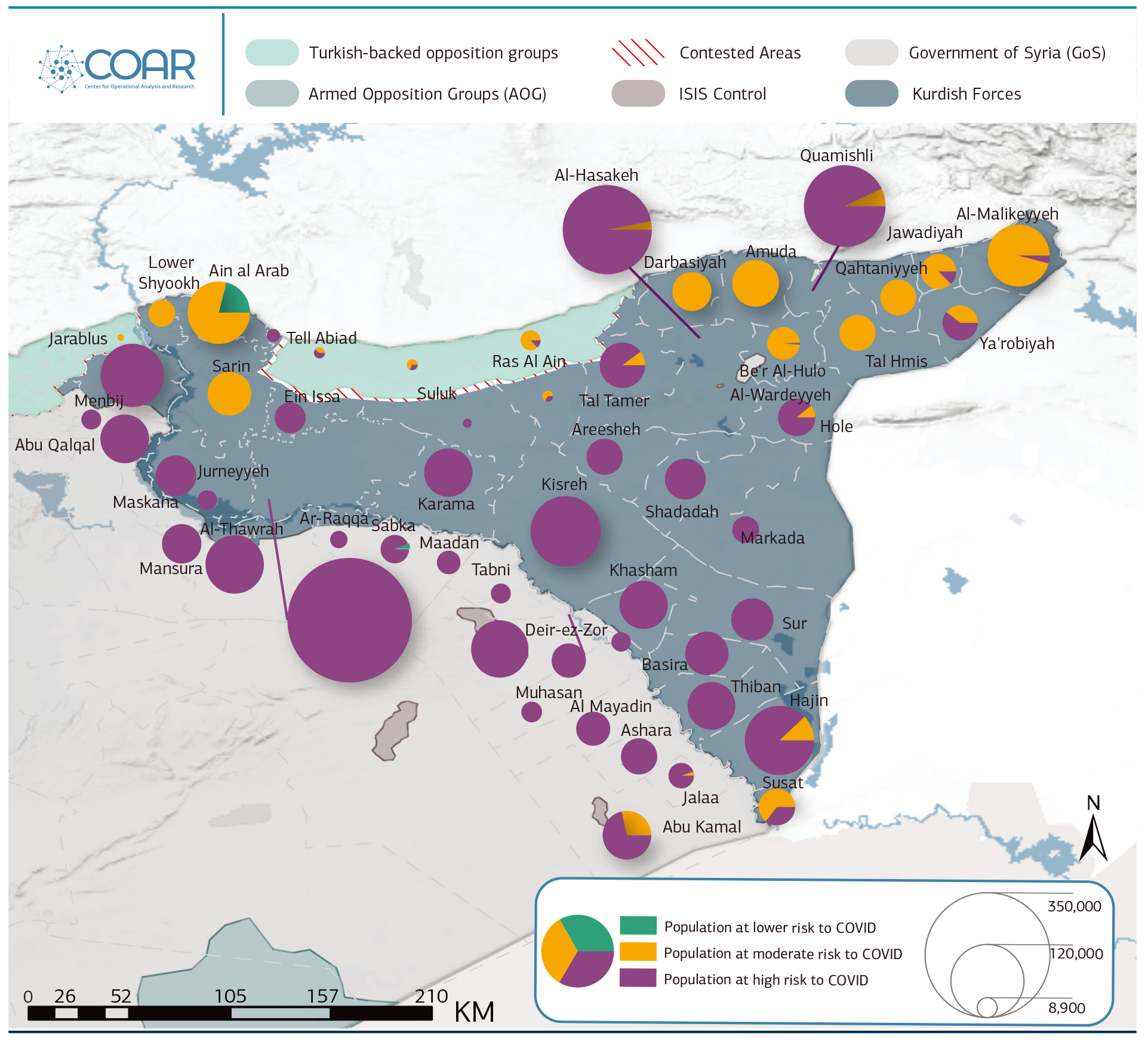

Though these are positive steps, they are scraping the edge of what the HEA is able to achieve independently. COVID-19 has exposed the Self-Administration as a proto-state, uncertain of its fate and reliant on its partners, exercising mixed authority through its nascent governance model. These features, which have also been revealed by other phenomena, go a long way toward explaining why the advice of a dedicated HEA Technical Committee is actionable only to the extent that local circumstances allow, why lockdowns are more readily enforceable in Kurdish-majority Al-Malikeyyeh than in Arab-majority Deir-ez-Zor, and why the prevalence of makeshift private health facilities in Ar-Raqqa precludes the kind of public health coordination possible in the comparatively well-resourced Quamishli.

The HEA presides over a fragmented region in which health governance capacity is variously determined by acutely local social, political, and material conditions. In theory, the Self-Administration’s decentralised governance model is designed to absorb such variations. In reality, local differences are sometimes so great as to disconnect the central offices of the HEA from their subsidiary district-level structures, resulting in a markedly different presence across the region and a disjointed pandemic response by the Kurdish-led authorities.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the northeast’s Government-held enclaves. The seemingly ad hoc distribution of authority in these areas is widely blamed for undermining HEA efforts to suppress COVID-19, as the Syrian Government has refused to adhere to HEA preventative measures at Government-run health facilities, checkpoints, and ports of entry.[26]Most notably, the Syrian Government refused to close Quamishli airport to passengers arriving from Iran, after that country became a COVID-19 hotspot. Suspicion that this behaviour deliberately seeks to politicise the pandemic in order to destabilise the Self-Administration is rife, yet the broader political compromise between the two parties means the Self-Administration has been powerless to respond. Claims that Damascus allowed COVID-19 to enter the region unchecked have therefore been met with silence; the Self-Administration has been forced to turn to international partners for resources that the Government has denied; and HEA pandemic surveillance has been limited to its own haphazard systems, owing to the unresponsive attitude of parallel services in Government-controlled areas.[27]Syrian Government RRTs were reportedly instructed not to collect samples from hospitals administered by unregistered NGOs, including major response actors like the Kurdish Red Crescent. Sources … Continue reading

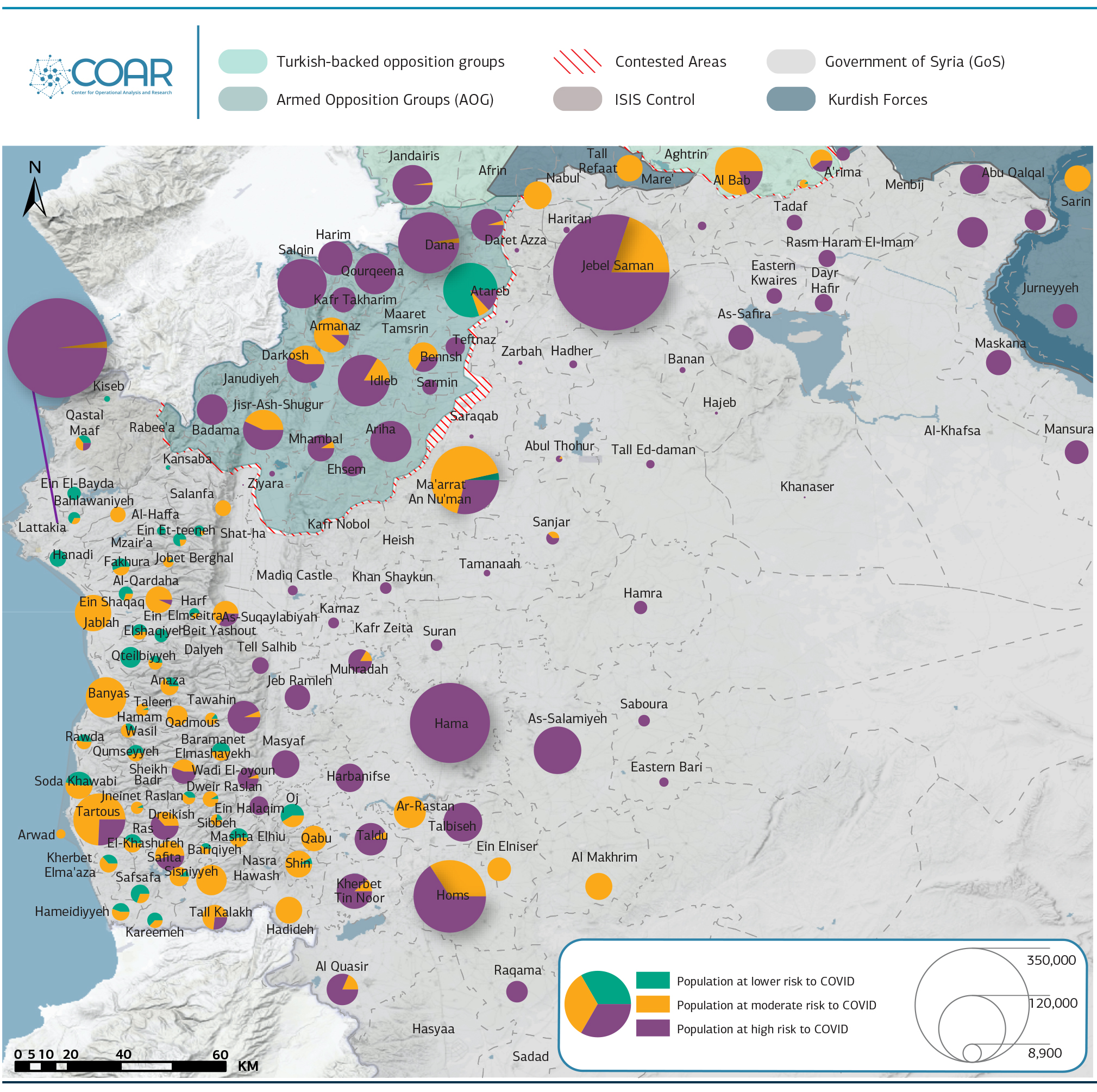

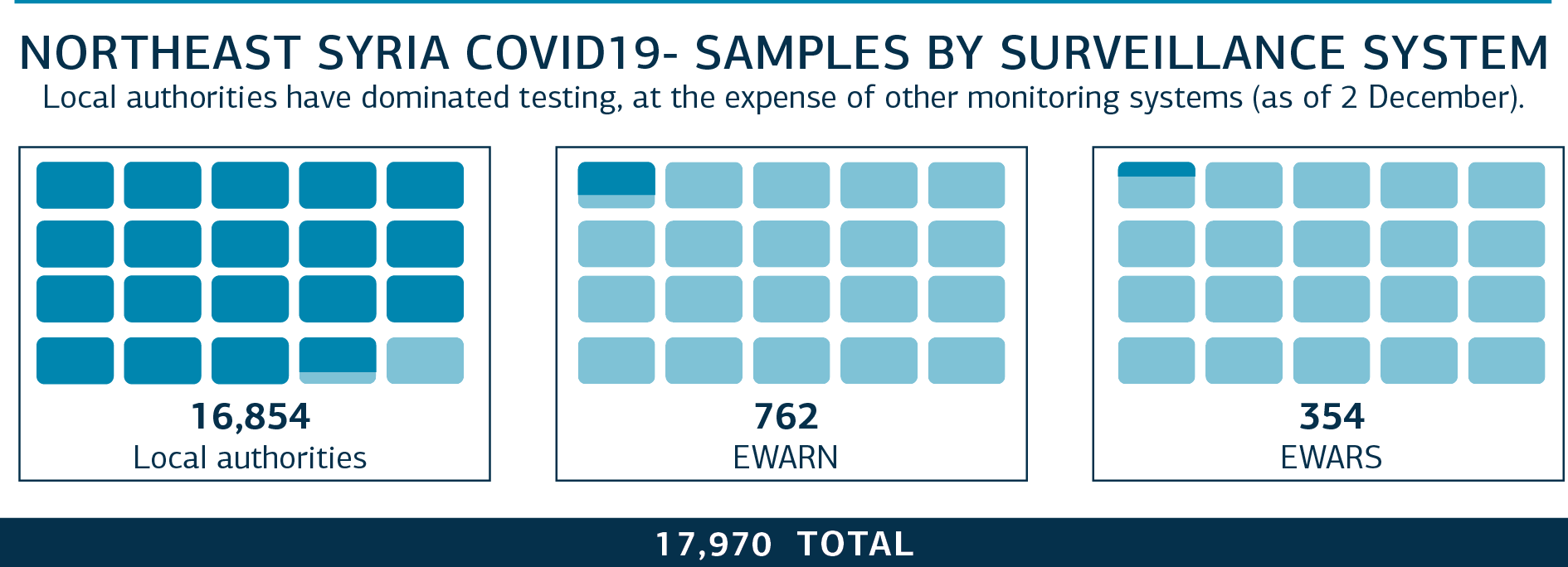

Box 4: Weak NES SurveillanceSeveral pandemic surveillance mechanisms variously linked to different Syrian governance bodies are in use in the northeast. The primary system is administered by the northeast’s own local authorities, which receive and return the great majority of tests for the region via a Quamishli-based lab. Secondary systems include alerts from the WHO and Syrian Government–run EWARS system and the supposedly “opposition-affiliated” EWARN system of northwest Syria. Interestingly, despite the conflict between Turkish-backed opposition and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), more tests from the northeast have been verified in Idleb following EWARN alerts than have been carried out in Damascus following EWARS alerts. The bulk of these northeast Idleb-processed tests have tended to be from underserviced Arab-majority areas such as Deir-ez-Zor, suggesting that the Self-Administration has been happy to allow the testing of these areas to be outsourced to the Arab-majority opposition.[28]WHO and UN OCHA, “Syrian Arab Republic: COVID-19 Response Update No.13,” 9 Decembcer 2020. Like EWARS, EWARN receives support from the WHO, as well as the Assistance Coordination Unit and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Despite offering theoretically comprehensive coverage, these systems are not aligned, leading to probable overlap, duplication, and overall surveillance inaccuracy. Moreover, the Government-linked EWARS system does not share information with the HEA as a matter of course, thereby failing to capitalise on an opportunity to enhance coordination across governmental authorities. It is worth noting that rapid diagnostic tests unsuited to COVID-19 detection were used by local authorities across the northeast early on, likely resulting in delayed diagnosis, hospitalisation, and treatment. According to local sources, humanitarian partners were attempting to dissuade local authorities from using such testing systems as late as October 2020. Such accounts highlight the limited local capacity — which is evidenced, too, by reports that district-level health committees have advised that suspected cases under the age of 40 should not be tested (as in Al-Hasakeh). |

Intra-Regional Response Management

The reach of the HEA is similarly uneven outside of Government-held pockets. In Deir-ez-Zor, for instance, the local HEA committee has reportedly been left largely to fend for itself, meeting just twice with other higher-level governmental bodies to address the COVID-19 challenge.[29]In Ar-Raqqa, too, the only dedicated COVID-19 isolation and treatment facility reportedly receives little support from the HEA. Note, the WHO states there are six such facilities in Ar-Raqqa … Continue reading Such limited coordination likely has important knock-on consequences: According to recent WHO figures, COVID-19 case numbers for Self-Administration-run parts of Deir-ez-Zor do not indicate a rate of infection commensurate with population size, the historically poor state of local sanitation systems, and the continuing mobility offered by numerous unofficial crossings into Government-controlled Syria. By 27 November 2020, HEA surveillance in Al-Hasakeh had recorded 4,283 positive cases of COVID-19, while just 129 cases had been identified in Self-Administration-run parts of Deir-ez-Zor.[30]WHO and UN OCHA, “Syrian Arab Republic: COVID-19 Humanitarian Update No.21,” 30 November 2020.

It is unclear whether this imbalance is a function of Deir-ez-Zor’s more peripheral importance to Kurdish political ambitions in Syria, its Arab-majority population, or its severe infrastructure shortfalls. A combination of these factors seems the most likely explanation. Deir-ez-Zor shares these characteristics with Ar-Raqqa and Menbij, both of which are described as having experienced similarly poor institutional support from the Self-Administration and a weak pandemic response. Just one dedicated COVID-19 facility is reportedly operational in Ar-Raqqa; it is said to receive little support from the HEA.[31]Local sources report there is just one RRT in Ar-Raqqa, financed by Relief International. This contrasts with numbers reported by the WHO, which counts four such teams. This discrepancy may be … Continue reading Similarly, in Deir-ez-Zor, there are no official RRTs; instead, four ad hoc groups operate under the auspices of the local health committee. Many of these workers have gone unpaid, however; they therefore operate as semi-volunteers and have previously resorted to strike action. Meanwhile, Menbij has watched on as its neighbour Ain al-Arab (Kobani) — just an hour away — has mounted a more robust response to COVID-19, despite the ravages the latter suffered during the 2015 battle for the city. True, international efforts to reconstruct Kobani are a factor in its superior COVID-19 response, but the clear differences in healthcare capacity do not appear to have prompted the Self-Administration to direct greater attention to needs in Menbij.

Intra-regional differences of this kind have naturally given rise to questions of bias within the Self-Administration’s pandemic response. Certainly, there is some evidence to suggest that the HEA has sought to prioritise core Kurdish areas like Quamishli and Al-Hasakeh. Early on, the HEA distributed PCR machines to Ar-Raqqa, Deir-ez-Zor, and Menbij, only to recall them to Quamishli shortly afterwards and ban any further unauthorised PCR imports. Local testing capacity in these locations has therefore remained minimal, a situation compounded by the fact that samples are reportedly sent to Qamishli just once or twice a week. According to the authorities, this approach was taken because the Quamishli laboratory is best placed to deliver higher total testing volumes. However, it has increased the challenges of tracing, quarantine enforcement, and community management for other municipal authorities, and most notably for those that have yet to fully buy into the Self-Administration governance project. One source cited claims that the recall of PCR machines from Arab-majority areas was prompted by (implausible) fears that they might be captured by ISIS and re-engineered for the purpose of developing biological weapons.

Much as in Government-held areas, less frequent testing outside core Kurdish communities likely obscures the scale of community transmission, thereby reducing some of the pressure on the Self-Administration to respond where its legitimacy is weakest and its base of popular support is most limited. The extent of such politicisation is difficult to measure, however, especially when set against distinct resource differentials between Kurdish and Arab communities. Indeed, resource-related differences are indicative of a double disparity in health coverage, which compounds a nationwide rural-urban divide that pre-dates the conflict, as in Government-held areas. Both Kurdish and Arab communities may therefore report shortages in the kind of infrastructure, staff, and material resources necessary for effective pandemic response, but local reports suggest the shortfalls are far more debilitating in Arab-majority places like Deir-ez-Zor and Ar-Raqqa than in Kurdish-majority areas like Quamishli and Ain al-Arab.

Politics of Human Resources for Health

In many respects, resource deficits in Arab-majority areas of the northeast are symptomatic of the greater damage, destruction, and deprivation these areas have experienced over the past decade. In terms of human resources, for example, there are reportedly no qualified anaesthetists or pulmonologists in Self-Administration-controlled portions of Deir-ez-Zor; a former geography teacher is the head of Ar-Raqqa’s HEA health committee; and training of new and existing generations of medical professionals is practically nonexistent given that there are few available training personnel and that formal health education in these areas has deteriorated to the point of near irrelevancy.[32]The only higher education institute providing formal medical training is Rojava University, in Quamishli. This university is not recognised by the Syrian Government, meaning its accreditations have … Continue reading

Retention of quality healthcare professionals is especially poor, as practitioners prefer to work in locations where there is greater stability and investment — either in northern parts of the Self-Administration or elsewhere in Syria. Besides a lack of human resources, one could also point to a range of further material and practical shortcomings in Arab-majority areas, including heavier reliance on costly, unregulated, and makeshift private healthcare as opposed to free I/NGO- or HEA-run facilities, as well as an exhaustive list of supply and equipment shortages.

At times, however, differences between Kurdish and Arab areas are indicative of the conflict-related dynamics that continue to dog the Self-Administration and militate against its more assertive leadership of a region-wide pandemic response. Anecdotal evidence suggests that some Arab doctors refuse to work for the Self-Administration, likely because of concerns for their longer-term protection in the event of the Syrian Government’s return to power in the northeast (or parts thereof). These fears are well-founded, as the experience of reconciled communities suggests perceived opposition sympathisers will be arrested, conscripted, and/or prohibited from returning to work if such steps are deemed prudent by Government security services.[33]Where the government has recovered territory, it has forced residents and even organisations to undergo “reconciliation”, a process intended to pacify opposing political and military elements and … Continue reading The limited popularity of the Self-Administration in some predominantly Arab tribal communities can also reportedly result in the disregard of HEA guidance and directives in both care settings and the community. According to local sources, antipathy toward Kurdish leadership may even extend so far as to dissuade prospective COVID-19 patients from using Self-Administration-linked Kurdish Red Crescent health facilities.

Box 5: Underuse of Dedicated COVID-19 Facilities

A WHO February 2021 update stated that less than 5 percent of beds in northeast Syria’s 17 dedicated COVID-19 facilities were occupied.[34]WHO and UN OCHA, “Syrian Arab Republic: COVID-19 Humanitarian Update No.23,” 1 February 2021. This low occupancy rate was reportedly due to mistrust and fear of infection in dedicated COVID-19 facilities, limited self-reporting by the public, and referral delays by local public and private hospital services. When self-reporting, patients often have to visit several facilities before gaining admission into a COVID-19 facility, and may ultimately abandon the effort altogether (cost of travel is frequently cited as a major barrier to healthcare access in the region). This increases reliance on underregulated facilities, where the enforcement of protocols for the diagnosis and referral of cases is generally poor, and where staff often lack the training to work safely with COVID-19 patients. Indeed, a number of clinics and hospitals in the northeast have been forced to close temporarily owing to the high rate of infections among medical staff.[35]WHO and UN OCHA, “Syrian Arab Republic: COVID-19 Response Update No.13,” 9 December 2020. These facilities were located in Al-Hasakeh, Kobane, and Ar-Raqqa |

Regional and International Coordination

The HEA convenes a weekly technical committee to coordinate the activities of HEA district-level directorates and to advise local COVID-19 committee groups. Local committees provide operational leadership at the community level, focusing on risk communication and community engagement, case investigation, rapid response team deployment, and infection prevention and control in healthcare settings. In most areas, COVID-19 committee meetings take place every week, but their activities are variously constrained by the issues raised in previous sections of this report and are broadly secondary to internationally led pandemic response initiatives.

Many I/NGOs engaged in COVID-19 response in the northeast operate within the Health Working Group, a civil society formation that predates the COVID-19 pandemic and focuses on humanitarian and development assistance in the health sector. Alongside the Northeast Syria Forum — the primary coordination body for I/NGOs in northeast Syria — the Health Working Group directs a COVID-19 Task Force responsible for implementing WHO response guidance and supervising relevant sub-committee bodies.[36]These sub-committees include: risk communication and community engagement (RCCE), case management, case investigation, and infection prevention and control (IPC). In addition to its international partners, the Health Working Group variously coordinates with the Health Cluster in Gaziantep, WHO Damascus, and the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Given that the Syrian Government’s involvement in the northeast’s pandemic response has been restricted mainly to EWARS and a few limited SARC operations, these partnership arrangements have been critical to the region’s pandemic response.

Although it has been at the centre of the northeast’s response, the Health Working Group has been criticised for its limited development of technical support for local bodies and for failing to adequately represent local committee interests at the COVID-19 Task Force. One local source notes that the HEA neglects to share certain categories of information — for instance, regarding the administration and transfer of PCR machines — with the Health Working Group. Such inefficiencies are clearly a matter of concern, given the extent to which the HEA has welcomed material and administrative support from international partners, not to mention its openness to the “capture” of health and related services by I/NGOs. Indeed, the Self-Administration is unlikely to be in a position to independently resource an adequately functional health service for some time (if ever). Such misalignments are therefore likely to have particularly acute consequences; they underline the importance of improved coordination ahead of future health emergencies.

After Ya’robiyah: Supply and Logistics

International agencies and their Syrian partners face a range of obstacles in providing support to the Self-Administration, many of which can be traced to the closure of Ya’robiyah crossing, pursuant to UN Resolution 2504, in January 2020. The closure of Ya’robiyah resulted in a 30 million USD shortfall for the region’s health sector and the suspension of UN cross-border support via northern Iraq. It also limited the ability of international aid agencies to secure UN assistance from the Syria Cross-border Humanitarian Fund and the Global Humanitarian Response Plan.[37]HRW, “Syria: Aid Restrictions Hinder Covid-19 Response,” 28 April 2020. By June 2020, just 31 percent of facilities previously supported through Ya’robiyah were receiving support via UN agencies’ cross-line land deliveries.[38]Figure presented in an open letter to the UN Security Council by several international aid agencies in June 2020. This has significantly increased reliance on the MoH for medical supplies and equipment, but this option has not been sufficient to meet needs in the northeast. UN agencies stated they would work to cover any resulting shortfalls, yet respondents estimate supplies entering the region may be down by as much as 40-50 percent as compared with late 2019.

Hopes that COVID-19 would bring the issue of supply and logistics back onto the table have been dashed by the continued obstinacy of parties to the conflict. Indeed, occasional Government-sanctioned WHO shipments to the northeast represent unusual gestures of goodwill, and are taken by some as a sign that a more sustainable solution to medical supply needs and other logistics may not be forthcoming. For the time being, informal Iraqi crossing points provide the HEA’s only reliable alternative for the receipt of internationally procured medical supplies. Notably, private sector healthcare providers face even greater medical-procurement challenges, and they are forced to not only overcome the same cumbersome sanction bureaucracies affecting I/NGO operations, but must also absorb the additional cost of import tariffs and supply-chain costs.

The region faces significant logistical challenges. In many cases, it has proven difficult to introduce medical technology and digital protocols, as services are often ambiguously defined across the different tiers of healthcare provision. Health information systems are outdated and there is no central referral system. Meanwhile, there are significant deficiencies in the quality control and procedural specifications regulating the entry of medical supplies into the region and ensuring that they match requirements. The procedures by which each hospital procures supplies are largely ambiguous and vary on a case-to-case basis. Furthermore, there is no unified vaccination programme across the northeast, and there is similarly an absence of malnutrition tracking and monitoring programmes, despite all the conditions for malnutrition being present in the region. Finally, although health workers are technically forbidden from engaging in dual public-private practice, this rule is not enforced; the same applies to mask mandates (though the extent of enforcement varies according to sub-region).

Box 6: CampsTo date, 58 COVID-19 cases have been reported in the northeast’s displaced persons camps. Thirteen of these were recorded in the most infamous and populous camp, al-Hol, which has also witnessed four COVID-related deaths.[39]WHO and UN OCHA, “Syrian Arab Republic: COVID-19 Humanitarian Update No.23,” 1 February 2021. According to the WHO, “confirmed cases have been recorded in five separate phases, indicating that it may be impossible to contain the virus through isolation and contact tracing alone.” Camp residents typically avoid moving to isolation areas due to security fears; do not follow precautionary measures, such as wearing face masks; and are thought to underreport their symptoms. It is unlikely that testing in camps where IS-linked detainees are present will be prioritised, giving rise to widespread concern over the fate of camp residents and the ability of response actors to contain more serious outbreaks. More recently, the WHO has stated that it has moved from “prioritizing containment — with an emphasis on testing, tracing and isolation” to “community surveillance” in camp locations.[40]WHO and UN OCHA, “Syrian Arab Republic: COVID-19 Response Update No.13,” 9 December 2020. Since the start of 2021, the WHO’s risk communication and community engagement activities have been suspended over security concerns.[41]WHO and UN OCHA, “Syrian Arab Republic: COVID-19 Humanitarian Update No.23,” 1 February 2021. |

Northwest Syria

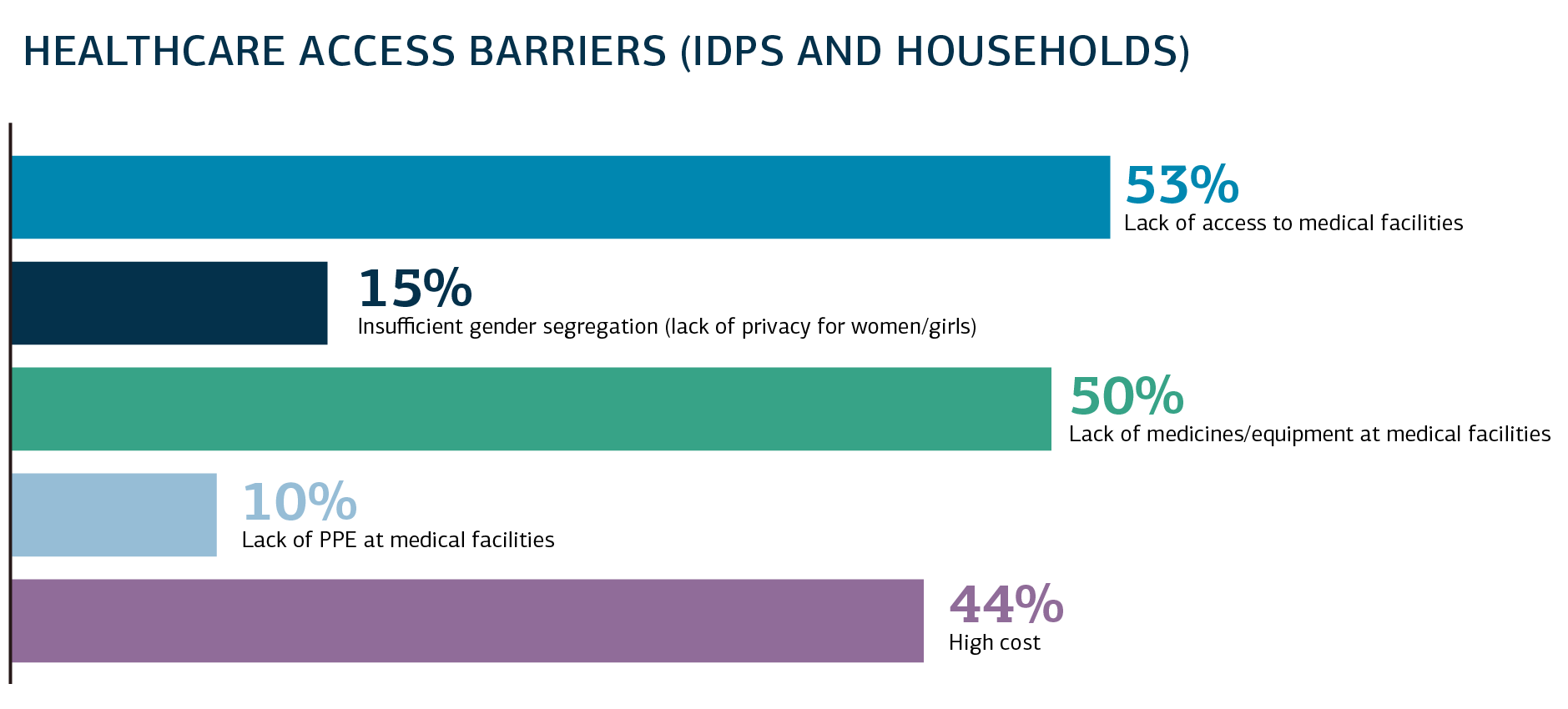

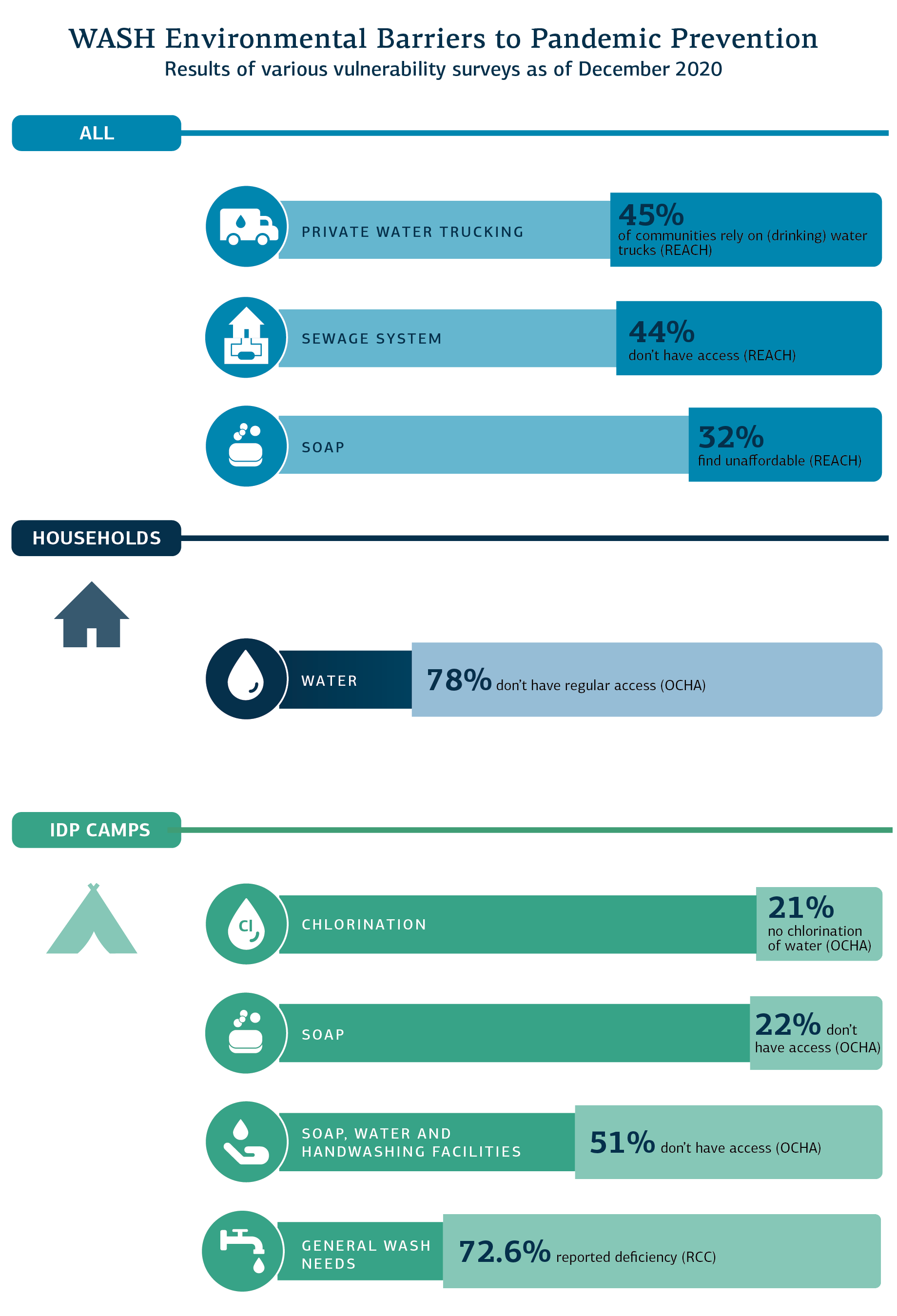

Opposition-controlled northwest Syria is home to between 4 and 5 million people,[42]Stabilisation Support Unit, “The condition in the Northern and Eastern Countryside of Aleppo Regarding COVID-19.” more than two-thirds of whom are IDPs in need of humanitarian assistance. Around half of the population in Idleb Governorate, for instance, live in tents and informal accommodation;[43]Mustafa Dahnon, “‘Before it’s too late’: Doctors in northwest Syria race to contain Covid-19 rise,” Middle East Eye, 13 November 2020. more than a million of these IDPs reside in overcrowded camps along the Turkish border.[44]CCCM Cluster, “Camp management guidance notes on COVID-19 outbreak,” 9 April 2020; UN OCHA, “Syrian Arab Republic: Northwest Syria Situation Report No.23,” 21 December 2020; and Response … Continue reading Besides large numbers of internally displaced people, northwest Syria’s demography also includes a relatively large number of people from other vulnerable groups. Women and children represent three-quarters of the population, while one-quarter of all people in the region are living with some form of disability.[45]UN OCHA, “Syrian Arab Republic: Northwest Syria Situation Report No.24,” 26 January 2021.These demographics suggest the region may be uniquely vulnerable to knock-on effects in case of a more severe rate of COVID-19 infection than is presently being reported. These conditions also underline the compound risks posed by ongoing problems of poor regional health access, supply and equipment shortfalls, and the unaffordability of even basic healthcare — let alone potentially prolonged treatment for COVID-19.[46]According to a January 2021 report, 53 percent of households did not have access to healthcare facilities, 50 percent reported a lack of medicine or equipment at facilities, 44 percent reported the … Continue reading It must also be noted that regional health infrastructure has been decimated, with between 67 and 85 health facilities being targeted by Syrian Government and Russian forces since 2019 alone.[47]Syrian Network for Human Rights, “Syrian-Russian Alliance Forces Target 67 Medical Facilities in Northwest Syria,” 18 February 2020; Syrian American Medical Society, “Civilians, civilian … Continue reading

The first confirmed COVID-19 case in the area was reported in Idleb in July 2020; as of 26 January 2021, there have been 19,447 cases confirmed, including 380 deaths.[48]UN OCHA, “Syrian Arab Republic: Northwest Syria Situation Report No. 23,” 21 December 2020. Although northwest Syria is broadly categorised as falling under the control of the armed opposition, the response approaches in Idleb and Aleppo governorates have diverged widely. While opposition-held Aleppo Governorate is almost exclusively controlled by Turkish forces and the Turkish-aligned Syrian National Army (SNA), Idleb Governorate is mainly under the nominal control of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). As a region considered to be outside the direct umbrella of Turkish forces, Idleb Governorate has suffered significantly more infrastructural damage compared to Turkish-controlled rural Aleppo — which Russian and Syrian Government forces refrain from targeting to a comparable extent. Furthermore, while the Turkish government has been able to consolidate governance and administrative control over opposition-held Aleppo, HTS has been unable to follow suit in Idleb, despite its military supremacy. Bridging the space between the northwest’s parallel health systems is a key issue to be addressed by the international Syria response, while additional challenges abound due to the region’s extensive health infrastructure damage, bottlenecked training and accreditation pipeline, and the inefficient or lacking support provided through private-sector actors.

Recommendations

- Public health infrastructure investment should form an important part of strategic preparedness for future disease outbreaks in northwest Syria.[49]Oxygen generators, for instance, have been identified as a major gap in the local response to COVID-19 and are likely to be necessary to combat other airborne diseases.

- Increase support to EWARN to enhance its role as the fulcrum for regional public health emergency alert, monitoring, and response functions.

- Invest in accredited higher education institutions and training programmes to address human resource shortfalls and offset the problem of unrecognised qualifications acquired in opposition-held areas. Such efforts must be accompanied by complementary professional opportunities and earning potential.

- Improve community outreach through long-term support for primary healthcare and mobile clinics.

- Enhance community awareness of vaccination campaigns and combat misinformation.

- Support private health sector development as a means to reduce dependence on aid in the absence of more robust public health sector capacity.

- Invest in pharmacists as frontline healthcare workers, including their expanded involvement in vaccination campaigns.

- Advocate for the creation of an independent technical body to formulate and unify public health policy and emergency response capacity across northwest Syria, ensuring buy-in from all de facto authorities.

A Tale of Two Governorates

Idleb: HTS Is More Pragmatic — and Weaker — Than Assumed

In Idleb Governorate, Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham and its affiliated Salvation Government (SG) have largely refrained from interfering in the COVID-19 response. With rare localised exceptions,[50]Such as in Sarmin, in August 2020. full lockdowns have not been applied as a matter of policy and the enforcement of general restrictions, such as the closure of schools and markets, has been inconsistent. To a great extent, this is because there is no unified governance authority capable of sustaining a decision to enforce a lockdown, especially at a time when the public are struggling to meet their most basic needs. Much like the Government of Syria itself, Idleb’s nominally dominant power, HTS, does not wield a complete monopoly of governing authority; rival factions (notably the National Front for Liberation) continue to exercise influence in various localities, even while nominally recognizing the supremacy of HTS. Local councils falling within the SG’s purview thus exercise various levels of autonomy. During the early days of the pandemic, HTS took the pragmatic step of shutting down Friday prayers, prompting criticism from hardliners. Prayers in areas held by more hardline groups reportedly continued.[51]Elizabeth Tsurkov and Qussai Jukhadar, “Ravaged by war, Syria’s health care system is utterly unprepared for a pandemic,” Middle East Institute, 23 April 2020.

In part because of the Salvation Government’s lack of major involvement and the autonomy provided to I/NGOs and CSOs in Idleb Governorate, the COVID-19 response has been marked by a notable degree of transparency. Furthermore, there are few suggestions of attempts to undermine response actors. The main local response deficiency lies in the lack of a central coordinating mechanism and authority: I/NGOs often operate autonomously, while health directorates are largely independent of the Syrian Interim Government (to which they are nominally subordinated, despite their presence in Salvation Government–administered territory) and of one another. Health directorates are largely relegated to a coordination role — often based on the good-will cooperation of I/NGOs — rather than playing an administrative and regulatory one.

This decentralisation of military and security control is similarly reflected in matters of governance and service provision, further complicating the landscape. Despite the nominal authority of the SG in the region, health and educational directorates continue to be nominally subsumed under the umbrella of the Syrian Interim Government (SIG). In practice, these definitions can be exaggerated; health directorates (especially the Idleb Health Directorate) are largely autonomous from the SIG and receive little support from it. Some educational facilities are directly supported by the SG and thus follow its authority, while others are affiliated with the SIG (indeed, some school directors are affiliated with both the SG and SIG).

Authorities in northwest Syria closed schools in March 2020 — following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic — until June. Following the declaration of the first case in the region in July, schools shut down again. A medical emergency was declared in the region early on; this entailed the suspension of “cold” (non-essential) operations, the shuttering of outpatient clinics, and the cancellation of vacations for medical staff. However, the actual implementation of these measures was sparse, uncoordinated, and largely left to individual I/NGOs. The lack of centralised coordination further led to ambiguity and disagreements between I/NGOs on the implementation of basic SOPs, such as the level of severity cases had to surpass in order to be admitted to ICU.

Schools reopened in late September, and cases reportedly increased in the following few weeks. Closures of schools and universities reportedly took place again in Idleb under the SG in November.[52]Mustafa Dahnon, “‘Before it’s too late’: Doctors in northwest Syria race to contain Covid-19 rise,” Middle East Eye, 13 November 2020. In December, the SIG declared that schools would be shut down again between 19 December and 15 January. However, the SG did not follow suit, and schools and universities have remained open in Idleb Governorate, with SG officials reportedly visiting university classes.

Restrictions on both international and internal crossings have fluctuated. As of February 2021, the Bab al-Hawa border crossing is partially open for commercial and humanitarian traffic, while the Bab al-Salama border crossing is open for commercial traffic, but with restrictions on humanitarian staff; each organisation is only permitted to cross on two days a week, with two staff members per vehicle.[53]WHO and UN OCHA, “Syrian Arab Republic: COVID-19 Response Update No.13,” 9 December 2020. The Bab al-Salama crossing has been closed to UN aid agencies since July 2020, after the UN Security Council failed to renew its mandate due to a Russian veto.

Aleppo: Marginalisation of I/NGOs and the SIG

In Aleppo Governorate, Turkish authorities have largely controlled the COVID-19 response. Local health directorates are placed directly under the supervision of adjacent Turkish provincial health directorates, which also directly administer hospitals and medical facilities across Aleppo Governorate. INGOs play a limited role, due to their reluctance to operate under heavy Turkish supervision. Numbers of suspected and confirmed cases cannot be published without the approval of the Turkish health authorities. Complaints have been voiced of extensive Turkish intervention and a lack of coherence in the response, with a high turnover of directors at Turkish provincial health directorates and reported competition between the various Turkish health directorates, leading to routine bureaucratic delays and requiring humanitarian actors to secure access “re-approvals”. The SIG lacks the capacity and resources to implement effective administrative, legal, and regulatory structures and mechanisms, and has — in this regard — been largely unsupported by Turkey, which has aggregated this role for itself. The heavy interference of Turkish authorities has, according to one local source, led groups including the Syria Recovery Trust Fund (SRTF) to retreat from providing support to Aleppo Governorate. (In the case of the SRTF, this is because the fund is only meant to support the capacity development of Syrian organisations.)

Leading Response Actors

In Idleb Governorate, the response has been steered by the Gaziantep-based WHO-led Health Cluster (which has 131 partners, including 35 INGOs, 49 NGOs, and 9 UN agencies) and the Assistance Coordination Unit (ACU), which utilise EWARN. The Idleb Health Directorate (IHD) coordinates the response on the ground. Civil society organisations have been able to support I/NGOs and the IHD without interference; their work includes community engagement and awareness-raising initiatives, sharing financial and human resources, and facilitating access to health facilities and community isolation centers.[54]Mazen Gharibah and Zaki Mehchy, “COVID-19 Pandemic: Syria’s Response and Healthcare Capacity,” Conflict Research Programme, LSE, 25 March 2020. The lack of interference is due both to a pushback against historical HTS/SG interference by I/NGOs and the SG’s limited capacity to take a leading role. There is a reported lack of coordination between I/NGOs on the ground, with no point of authority integrating the whole response.

Despite its limited resources, the IHD has succeeded in implementing clear clinical definitions of cases (both suspected and confirmed) in addition to “clinical standards of procedures on how to triage, refer, workup diagnosis and possible treatment protocols.”[55]Abdulkarim Ekzayez, et al., “COVID-19 response in northwest Syria: innovation and community engagement in a complex conflict,” Journal of Public Health, 21 May 2020. This is attributed to the organisation having a significant degree of legitimacy among both healthcare workers and communities in Idleb Governorate, having worked for seven years under difficult circumstances and sought to embrace all doctors in the region. In coordination with actors such as the Syrian Civil Defence (White Helmets), the IHD launched a “volunteers against corona” initiative that mobilised thousands of volunteers across Idleb, dividing them into neighborhood committees and technical crews.

Meanwhile, the Aleppo Health Directorate (AHD) is closer to a medical organisation than an administrative body; it focuses on the Operation Euphrates Shield areas, as opposed to Afrin and the western Aleppo countryside. Afrin is subordinated to the Hatay Health Directorate, Azaz to the Kilis Health Directorate, and Jarablus to the Gaziantep Health Directorate. One local source indicated that the Turkish authorities frequently attempt to control the information coming out of northwest Syria, and while there is no evidence of a cover-up, an administrative bureaucratic mindset prevails over a public health one.

The main surveillance system in the region is the EWARN system, which was set up in 2013 by the ACU and receives support and funding from the U.S., the CDC, and the Gates Foundation. Since 2017, EWARN had scaled up its alert capabilities for influenza and severe acute respiratory infections, leaving it relatively well-prepared — given its limited testing capacities — for the COVID-19 outbreak. However, there have been reports that EWARN initially struggled to collect samples, due to difficulties obtaining access approval from the Turkish authorities. One source attributed this in part to the high turnaround in directors at Turkish provincial health directorates.

The WHO response in northwest Syria was criticised at the start of the pandemic for delays in planning, producing projections, and providing testing kits. The WHO reportedly defended this delay during the early phase of the pandemic by stating that the organisation prioritises deliveries to government agencies, and “northwest Syria is not a country.”[56]Evan Hill and Yousour Al-Hlou, “‘Wash Our Hands? Some People Can’t Wash Their Kids for a Week’,” New York Times, 19 March 2020. During this period, the WHO failed to provide PCR machines to the region (eventually doing so in late 2020), requiring health actors in northwest Syria to send samples to Damascus.[57]Elizabeth Tsurkov and Qussai Jukhadar, “Ravaged by war, Syria’s health care system is utterly unprepared for a pandemic,” Middle East Institute, 23 April 2020. Eventually, the ACU procured a PCR machine. The WHO was also said to have taken a long time to distribute PPE, which only came into widespread use in August 2020. A medical source told COAR that the WHO often believes estimates by I/NGOs and local actors regarding the scale of needed support to be exaggerated (an example being the COVID-19 Task Force PRP drafted in March, which asked for 30 million USD), and recommends cheaper “plan Bs”.

Premature Optimism and Fears of a ‘Belated’ Collapse

Fears that the COVID-19 pandemic would quickly bring about the collapse of a health sector decimated by conflict and precipitate a humanitarian crisis more acute than in any other part of the country have not yet materialised. But a surge in cases since September has continued to multiply on a monthly basis, and there are widespread fears that northwest Syria — especially Idleb Governorate — is nearing breaking point. Cases increased by a factor of 20 between September and October 2020,[58]UN OCHA, “Syrian Arab Republic: Northwest Syria Situation Report No.21,” 20 October 2020. then a further 80 percent between October and November 2020,[59]REACH, “Humanitarian Situation Overview: Northwest Syria,” November 2020. and 47 percent between November and December.[60]UN OCHA, “Syrian Arab Republic: Northwest Syria Situation Report No.23,” 21 December 2020. As of December 2020, 23 percent of tested cases were positive,[61]WHO and UN OCHA, “Syrian Arab Republic: COVID-19 Response Update No.13,” 9 December 2020. and 28 percent of these positive results were for individuals living in camps.[62]UN OCHA, “Syrian Arab Republic: Northwest Syria Situation Report No.23,” 21 December 2020. While this massive increase in confirmed cases is attributed in part to increased testing and the opening of two new laboratories in the region, it clearly points to widespread community transmission — which took root later than might have been expected due to the relatively delayed onset of COVID-19 in the region. As noted, the first case in the northwest was identified in July 2020. The rate of increase in confirmed cases dropped significantly, to 7 percent, by January 2021, although the number of deaths increased by 47 percent.[63]UN OCHA, “Syrian Arab Republic: Northwest Syria Situation Report No.24,” 26 January 2021. Ten percent of all cases in the region are in camps and almost half of all cases are under the age of five.[64]WHO and UN OCHA, “Syrian Arab Republic: COVID-19 Response Update No.14,” 12 January 2021. The slowed increase in cases in January may be misleading: health behavior has been cited both by the OCHA[65]UN OCHA, “Syrian Arab Republic: Northwest Syria Situation Report No.24,” 26 January 2021. and by primary sources as one reason for the drop in cases, with an increasing number of people choosing not to go in for testing.