In-Depth Analysis

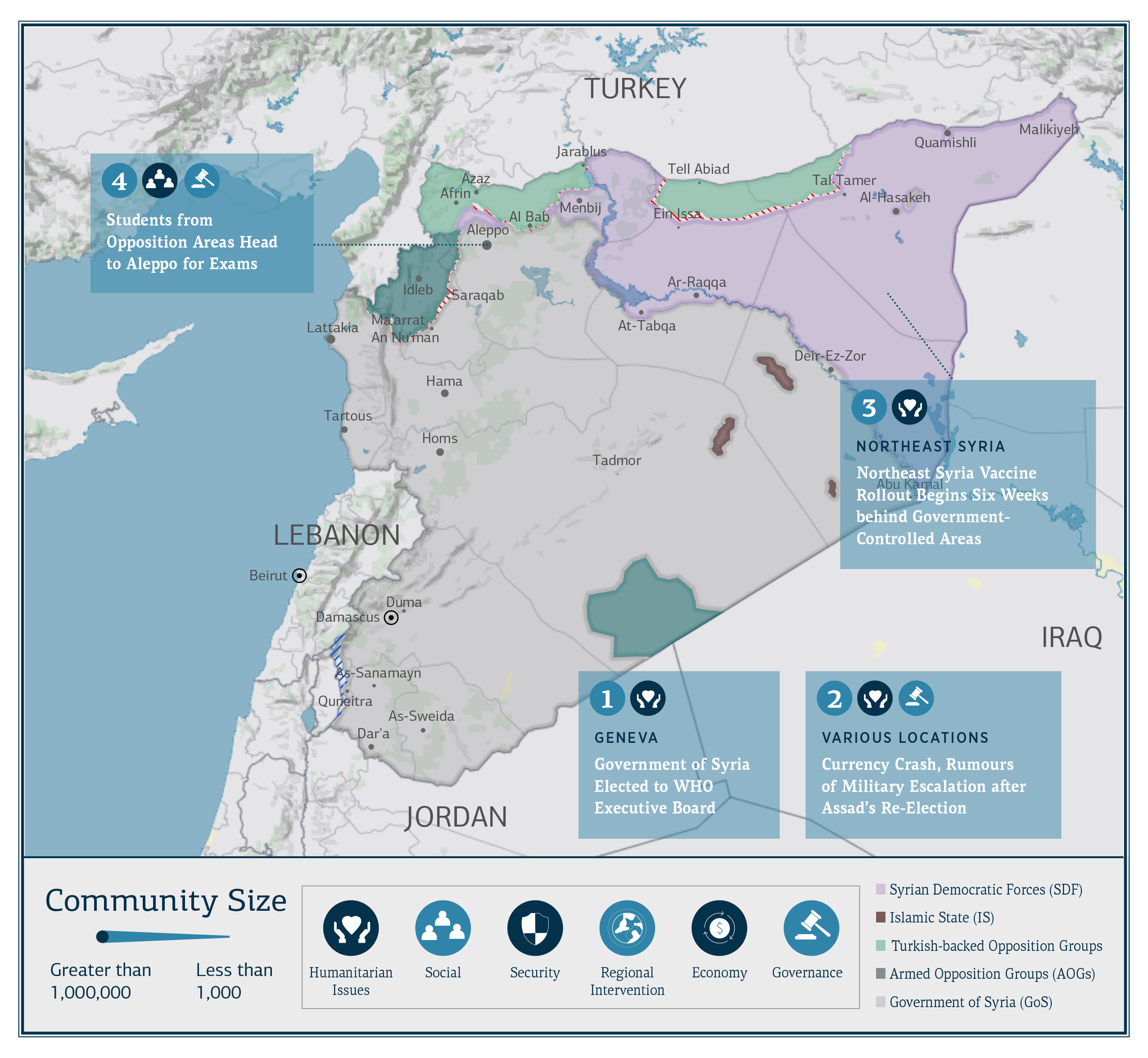

On 1 June, media sources reported that between six and eight people were killed, and at least 25 injured in Menbij when Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) sought to quell public demonstrations against military conscription. The protests flared in response to the implementation of a 3 May conscription decree issued by the Autonomous Administration Defense Bureau, one of many such orders calling on all males of conscription age to either enlist or submit a service waiver. Demonstrators took to the streets despite a 48-hour curfew imposed by the Menbij Military Council in a desperate attempt to control unrest. The ostensible trigger of the flare-up was a series of raids carried out by the SDF in search of conscription-age males. A general strike was called in the area on 31 May, coinciding with protests which lasted for three days and reached nearby towns such as Hudhud. On 2 June, the SDF, the Menbij Military Council, and the Menbij Civil Council reached a de-escalatory agreement with tribal figures and local notables, which entailed halting the conscription campaign, releasing individuals detained during the protests, and forming an investigative committee to hold those who shot protestors accountable. Those who led the popular resistance against the SDF campaign were not fully satisfied with the agreement, and have said that they would allow the SDF 10 days to meet their demands for more far-reaching concessions.

This was the second time in as many weeks that the SDF carried out a deadly crackdown on demonstrators challenging its authority in pivotal communities. Security forces responded similarly to the mid-May protests over a dramatic spike in fuel prices (see: Syria Update 24 May 2021). As is so often the case, the public actions against local security authorities have deeper underlying causes that will shape the operational environment for donor-funded projects and aid implementation. Blowback from the crackdown has been felt well beyond Menbij, and the violence has led to serious backlash on political, ethnic, and tribal levels. Not entirely without basis, the Autonomous Administration has claimed that “external actors such as the Syrian regime, Turkey and ISIS, are exploiting current events to take the demands of the people into the wrong direction.” Tribal figures affiliated with the SDF have issued a statement urging the people of Menbij to prevent external actors from destabilising their city. Among the public denunciations of the SDF’s response was a 1 June statement by 78 tribal, political, and civil society actors urging the international community to take the necessary steps to protect the people of Menbij. Groups representing tribes such as the Weldeh, Tayy, Afadleh, and Bakkara issued similar statements. All of the tribal actors that have taken a public stand against the SDF have some degree of engagement with Turkey or the Government of Syria — an indication of outside actors’ instrumentalisation of local political rifts (see: Tribal Tribulations: Tribal Mapping and State Actor Influence in Northeastern Syria).

Conscription and other grievances

Conscription has elicited collective action since the beginning of the year in various parts of northeast Syria, especially in eastern rural Deir-ez-Zor and Ar-Raqqa governorates. Teachers have been particularly resistant to SDF conscription campaigns, which has led to the detention and dismissal of a large number of educators by SDF security forces. However, military service is only one among many grievances. Inadequate provision of services and the corruption or ineptitude of Autonomous Administration entities have led to local discontent as well. In addition to the suspension of the conscription law, protesters in Menbij have demanded an end to duties on food and construction materials entering the city, the lowering of fuel prices, and the dismissal of corrupt Autonomous Administration officials. A pro-Turkey tribal entity in Menbij enumerated additional grievances against the Autonomous Administration, including neglect of education, the imposition of an alien culture, a supposed policy of demographic transformation, and the stoking of tribal disputes to further the Autonomous Administration’s own interests.

Conscription and education have been pillars of the Autonomous Administration’s strategy to solidify control, not least because they are crucial to incorporating the Arab population into its social, governance, and military structures. However, such policies have seemingly backfired, and they have been a major source of discord between Arab communities and the Autonomous Administration, undermining the latter’s legitimacy on the local level, providing recruitment opportunities for the Islamic State (IS), and catalysing efforts by Arab tribes to seek further independence from the Autonomous Administration (see: Northeast Syria Social Tensions and Stability Monitoring Pilot Project: March and April 2021 reports).

Menbij: the same, but different

Menbij can be viewed as a microcosm of the societal and administrative issues that plague the Autonomous Administration. However, it is distinguished by a unique blend of social and historical dynamics. Given its status as a major economic hub and transit center in northern Syria, it is one of the few large cities in the country that has been controlled by nearly every major conflict actor since 2011 (the Government of Syria, the Free Syrian Army, IS, and the SDF). The city has been deeply unstable since it came under SDF control in August 2016, and the struggle for power continues to be one of the main destabilising factors in the city. Actors such as Turkey, the Government of Syria, and Russia interfere with local tribal and political actors, capitalising on the disorder to strengthen their influence and delegitimise the SDF. At the same time, they continue to reinforce their military presence in the city’s outskirts, emboldening local resistance to the Autonomous Administration and posing a threat of direct intervention.

Another reason events have escalated in Menbij may be the deep involvement of its civil society in local politics since the outbreak of the conflict. The population of Menbij has consistently employed non-violent resistance tactics against the SDF’s conscription policy, including successful general strikes in 2017, 2018, and 2019. Cognisant of these factors, the Autonomous Administration and the SDF have prioritised containment in Menbij. The eruption of deadly violence and harsh crackdown in multiple areas of SDF control in the past month will prompt unease within the Autonomous Administration. Unless these forces can stem external interference, boost their local legitimacy, and better align their governance programs with the interests of reluctant local powers such as tribal leaders, authorities will find themselves increasingly consumed with the difficult work of confronting wider social unrest.

Whole of Syria Review

Government of Syria Elected to WHO Executive Board

Geneva: On 28 May, Syria was elected to fill one of 34 seats of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) executive board, sparking criticism of the organisation and the UN system’s politicisation in Syria. Joining a chorus of dissent, Germany’s Minister of Health was reported to be “anything but happy” with the decision, and Syrian health workers and activists held public demonstrations in the northwest. In addition, the Idleb Health Directorate staged a protest on 31 May to denounce the WHO’s decision. The Syrian opposition has formally denounced and criticized the move, although a more cautious Autonomous Administration — reliant on health aid delivered via Damascus — has not publicly commented as of the time of writing. Syria was one of twelve states to nominate members to the WHO’s executive board, and their selection was approved through a unanimous vote, without debate. The executive board implements the decisions and policies of the annual health assembly while also providing advice and facilitating the organisation’s work.

Disappointing decision

Syria’s inclusion in WHO’s global leadership is a major provocation that reopens old wounds surrounding the organisation’s politicisation and perceived failures in Syria (see: Syrian Public Health after COVID-19: Entry Points and Lessons Learned from the Pandemic Response; in particular, see the lengthy annex: Public Health Responses to Syria’s Past Epidemics). Health practitioners and public health professionals are reluctant to call out the failings of health actors, including the WHO, for fear of politicising life-saving care. Such fears are valid, but the unwillingness to speak honestly about such failings is a barrier to future accountability.

The WHO’s acquiesence to the Government of Syria’s restrictions on its operations has frequently resulted in unequal aid distribution between Government- and opposition-controlled areas. For instance, in 2012, the Government of Syria effectively shut down a joint WHO-UNICEF polio vaccination drive in rural Deir-ez-Zor, then a breakaway region under opposition control. WHO justified the exclusion of Deir-ez-Zor by claiming (speciously) that “the majority of its residents have relocated to other areas in the country.” Not surprisingly, the region became the epicentre in a polio outbreak that followed. Likewise, detection of the 2015 cholera outbreak in opposition areas was hampered by the WHO’s refusal to recognise diagnoses made without laboratory testing, despite the fact that adequate laboratory diagnostics were not available in opposition-held areas where cholera was believed to be rampant. These types of incidents are numerous and ongoing. Today, health and pharmaceutical support to northeast Syria is provided through WHO Damascus, and is subject to similar pressures and politicisation. Northeast Syria’s dependency on Damascus has led to delays, aid shortages, and disparities in the provision of COVID-19 vaccines (see: Syria Update 19 April 2021).

Aid actors of all stripes have been forced to make difficult decisions in Syria when faced with pressures from all sides. However, allowing Syrian Government figures to claim a leadership role in the same leading global health agency that Damascus has frequently undermined for its own benefit is especially provocative. The Government of Syria has arguably been more effective than any other conflict actor in shaping the aid system to its advantage on the ground in Syria. Its rise to a WHO leadership position shows that the aid system’s systemic fragilities exist on the global level, too.

Currency Crash, Rumours of Military Escalation after Assad’s Re-Election

Various locations: A snap currency crash and rumours of military escalation have circulated in Syria following the country’s 26 May presidential election (see: Syria Update 31 May 2021). As of 30 May, the Syrian pound has shed several percentage points against the dollar, leading to public concern over deeper economic retrenchment following Bashar al-Assad’s electoral “victory.” Meanwhile, on 28 May, Grand Mufti Ahmed Hassoun threatened northeast and northwest Syria with military operations, stating “I say to whoever stands with the occupation in northern Syria, you will see us there and in Idleb, sooner or later.” Syrian opposition figures and analysts alike have voiced concern that the Government of Syria will consider the election as an inflection point past which its de-escalatory tone and its toleration of the tenuous quiet on the frontlines with the opposition in Idleb are no longer necessary.

Election over, will the gloves come off?

Speculation has been rampant over the direction Syria will take following Bashar al-Assad’s re-election. Syrian media have been keen to seize on events such as the pound’s losses against the dollar, warning that further economic shock will follow. However, at the time of writing, the pound’s decline of roughly 3 percent has been less extreme than many have suggested. A second area of concern is military escalation, particularly in northwest Syria. Despite the statements made by Hassoun, there are as yet few concrete indications that Syrian Government forces are prepositioning or preparing to resume major military operations on the frontlines with opposition forces in Idelb, which is backed by a significant Turkish military presence. The Russian-Turkish military ceasefire agreement that has brought relative calm to Idleb since March 2020 is among the longest-lasting and most successful of the conflict, but analysts fear it to be weak. Shelling and bombardment remain possible in Idleb, but the most significant shift in conditions on the ground since the elections has occurred in southern Syria, not the northwest. Since the election, Government forces have deployed reinforcements to checkpoints throughout Dar’a, restricted mobility across Dar’a city, reduced the electricity supply in reconciled areas, and revoked travel authorisation for reconciled fighters. Signs of a harsher approach by Damascus are also apparent in the neighbouring As-Sweida Governorate. Media reports indicate that Major General Hussam Luka, head of Syria’s General Intelligence Directorate, will lead the new security committee that is designed to bring stability to the governorate. Luka’s appointment carries with it the implicit threat of force. These measures may reflect an eagerness on the part of Damascus to impose its will on the restive regions, and they suggest that post-election hostilities may come first not in the north, but the south.

Northeast Syria Vaccine Rollout Begins Six Weeks behind Government-Controlled Areas

Northeast Syria: On 30 May, 17,000 doses of COVID-19 vaccine manufactured by AstraZeneca and supplied through COVAX arrived in the northeast, more than a month after the arrival of vaccines in Damascus. This delay has prompted debate concerning the politicisation of health support to northeast Syria through Damascus, which remains the sole provider of medical aid to the region after the closure of the Ya’roubia border crossing between SDF-controlled areas and northern Iraq in January 2020. The head of northeast Syria’s Health Authority said that vaccines currently allocated to the northeast will cover about 10 percent of the population of Al-Hasakeh, Ar-Raqqa, and Deir-ez-Zor governorates. Meanwhile, 54,000 doses arrived in opposition-held areas of northwest Syria in late April via the Bab al-Hawa border crossing; just over 16,000 people have been vaccinated as of 31 May. Even in areas that have received a relatively large number of vaccines, this initial phase of distribution is largely limited to medical staff in hospitals and NGO workers. On 19 May, the Government of Syria announced that 81 centres would provide vaccines across areas controlled by the Government and in the northeast, which relies on Damascus as the gatekeeper of aid provided by the UN system.

Conditions in Government of Syria-held areas are substantially different. The Syrian Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) began administering COVID-19 vaccinations on 18 May after receiving several batches in late April. While the number of vaccines secured is not enough to cover all Syrians, donations have been promised from several external sources, including China and Russia (see: Syria Update 22 February 2021).

Vaccine skepticism: Ambiguity over Government rollout

The slow vaccine rollout in northeast Syria is indicative of the disparate access and aid provision that have been brought on by the elimination of cross-border aid. Without unfettered direct access for UN aid, the region has been brought under the thumb of Damascus. Meanwhile, whereas vaccine donations to Government-held areas and support to Syria’s pandemic response are well documented, information related to distribution in Government-controlled areas is scarce. Reporting from mid-April indicates that approximately 450,000 vaccine doses have been donated to Damascus by its international partners, but the Syrian Government has not yet reported the overall or regional rates of vaccination across its areas of control. Questions have been raised regarding politicisation and for-profit sale of vaccines, particularly given the Government of Syria’s tendency to monetise unconventional sectors as its other financial resources evaporate. Local sources report that AstraZeneca and Sinopharm vaccines are available for sale in Damascus for between 50 and 100 USD, or its equivalent in Syrian pounds.

Students from Opposition Areas Head to Aleppo for Exams

Aleppo: On 29 May, pro-Government media sources reported that 4,600 students arrived in Aleppo city from opposition-held areas in the Idleb and Aleppo countryside to sit for school certificate examinations. The Syrian Ministry of Education stated that it provided accommodation in 25 centres across Aleppo city for primary and secondary students coming from opposition-held areas. Of note, media sources reported that mobile phone and internet connections were to be severed across Syria during exams in order to prevent students from cheating. This decision has been criticised for its obvious economic repercussions. In another cheating-related event, Deir-ez-Zor’s Directorate of Education barred a local National Defense Forces (NDF) commander from taking the secondary school certificate examination as he had sent another NDF member to take it on his behalf. The NDF stormed the examination centre in response.

An annual controversy, growing divisions

The travel of students from opposition- to Government-held areas to take exams has sparked widespread controversy for years, but there are signs that the pragmatic tone of cross-line educational cooperation may be turning more hostile. Last year, a group of Idleb-based activists held a sit-in at the Mihrab roundabout to prevent students from entering Government-controlled areas to take their exams; they accused Government forces of arresting a number of students and assaulting female students. Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) also blocked some students from entering Government areas, stopping buses transporting female students and confiscating their examination cards. Salvation Government Minister of Education Adel Hadid has voiced the group’s intention to sever educational linkages with the Government, stating that it would not recognise certificates issued by the Syrian Ministry of Education. Moreover, last year, the Aleppo Directorate of Education dismissed staff who sent their children for exams in Damascus-controlled areas.

In terms of Syria’s overall political economy, the slide toward more fractious relations between the regions on matters of education suggests a hardening of regional boundaries. For students, the stakes are high. School certificates issued by the Government of Syria are a prerequisite to attend university in Government-held areas and are also a requirement for many jobs. Degrees from universities in Government-controlled areas are internationally recognised while those from universities in opposition-held territories are not, resulting in an annual influx of certificate-seeking students into Government-held areas.

Open-Source Annex

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below..

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

US Weighs Oil for Aid Bargain with Russia in Northeast Syria

What Does it Say? The article contends that the Biden administration is hoping that it can negotiate with Moscow to reopen cross-border aid via Ya’roubia and maintain the Bab al-Hawa crossing in exchange for pulling out of the Syrian oil fields.

Reading Between the Lines: Reopening cross-border aid from Iraq would be a crucial step toward delivering large volumes of aid to millions of people in northeast Syria. However, the swap: aid access along parameters desired by the US in exchange for leaving northeast Syria’s oil to Russia is highly speculative and almost certainly inoperative on the ground. Such theorising should be approached with extreme caution.

Revealed: Syrians Pay Taxes to Rebuild After War but See Little Benefit

What Does it Say? Syrians in Damascus-controlled areas have paid approximately 300 million USD in reconstruction taxes that were meant to be distributed to those whose homes were destroyed, but the money has almost entirely disappeared; investigators trace some portion of it to rehabilitation of military sites, rather than needy Syrians.

Reading Between the Lines: The conclusion is unsurprising; the Syrian Government has resorted to increasingly desperate financing measures, and it will continue to prioritise military and security activities as long as it remains locked in a war that it views as existential.

What Does it Say? The paper is a brisk and comprehensive distillation of the issues at stake with the renewal of the cross-border aid mechanism in northwest Syria, including instrumentalisation and aid politicisation by Damascus on one side, and concerns about sovereignty and aid diversion by HTS on the other.

Reading Between the Lines: Bab al-Hawa’s days are numbered, and the paper is correct in asserting that alternatives must be created, and fast. However, its contention that cross-line aid delivery can be managed at-scale or on a principled basis is dubious.

Mercenarism in Syria: Predatory Recruitment and the Enrichment of Criminal Militias

What Does it Say? The report discusses the use of Syrian mercenaries in foreign conflicts and the related phenomena of predatory recruitment, labour exploitation, and defrauding of families.

Reading Between the Lines: As the economic situation in Syria deteriorates, many battle-hardened fighters from all areas of control are seeking livelihoods through foreign military recruiters. The emphasis on exploitation is needed, given that many Syrians who have gone to fight abroad have encountered unexpectedly bad conditions and salaries that are a fraction of what they were promised.

Investigation Reveals Iran’s Deception About The Nature of Its Presence in Syria

What Does it Say? The article contends that although both the Iranian and Syrian governments have affirmed that Iran’s military presence in Syria is limited to an advisory role, evidence such as the construction of new Iranian military and security bases points to the contrary.

Reading Between the Lines: Although Iran’s active troop presence in Syria has decreased since the height of the conflict, Iran is cementing its influence through various economic, cultural, religious, and social projects.

Map of Explosions in Liberated Areas During May 2021

What Does it Say? A map showing the locations of the 10 explosions across opposition-held areas in northern Syria in May 2021.

Reading Between the Lines: Several bombs detonated in various locations in the north, demonstrating the chaos and danger that still exist despite the fact that major military operations in the area have been put on pause.

What Does it Say? The article details acts of child abuse in northwest Syria and notes, among other things, that a first step toward a solution would be the enactment of effective laws against child abuse.

Reading Between the Lines: The legal framework in northwest Syria is incomplete and fragmented, particularly given that the Salvation Government’s approach relies on local-level dispute resolution and Islamic law. As the Salvation Government develops, it may introduce a more comprehensive legal framework instead of relying on a patchwork of laws inherited from the Government of Syria and its own attempts at legislation.