In-Depth Analysis

On 5 June, local and media sources reported that hundreds of people gathered in Duma’s town square anticipating the release of detainees, as promised during the recent presidential elections by a prominent local sheikh on behalf of the Syrian Government. They left in disappointment and rage. Although local sources indicate that as many as 3,000 detainees from the area are now being held, media reports stated that no more than 14 individuals were released, all of them described by Damascus Governorate officials as not having “blood on their hands” — a thinly veiled reference to armed opposition to the Government. The incident stoked tensions in the community, which were already heightened due to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s deliberately provocative decision to cast his ballot in the 26 May presidential election in Duma, a former opposition stronghold that was violently brought to heel in 2018 (see: Political Demographics: The Markings of the Government of Syria Reconciliation Measures in Eastern Ghouta).

The incident invites renewed attention to the plight of Syria’s estimated 100,000 detainees. Though often treated as an intractable issue of secondary importance, detention remains one of the touchstone issues of the Syria conflict. Detainees undergo various forms of abuse, including physical violence, sexual assault, starvation, and psychological torture. The social and political impact of detention is no less significant. Although Damascus usually handles the detainee issue with sensitivity and obfuscation, the detainee file risks igniting social tensions, as many detainees are presumed dead. The longer the issue goes unresolved, the more pronounced its negative influence on accountability and inter-communal reconciliation efforts will become.

False promises, false hope

Detention is an issue of deep, nationwide impact in Syria, and the promise of detainee releases regularly features in negotiations between local security committees or state intermediaries and security authorities. However, the number of people who are ultimately released often falls short of the promises made by Damascus. In addition, the Syrian Government generally releases petty criminals and non-political offenders rather than those, far more numerous, whose sole offense is past affiliation with the armed or political opposition. The recent events in Duma are reminiscent of previous amnesties (such as Decree 20 in 2019) which were initially presented as sweeping, but resulted in few releases (see: Syria Update 23-29 October 2019). These failures have consequences. The lack of follow-through concerning detainees has consistently spoiled reconciliation deals and ad-hoc agreements to de-escalate tensions in restive areas, particularly in southern Syria. The pattern of broken promises suggests that high-ranking Government officials are willing to exploit communities’ distress over missing persons in order to impose stability and secure near-term conflict objectives, even though doing so creates the conditions for future unrest. In that sense, promising to release detainees merely kicks the can down the road, toward what may be an explosive reckoning. Large-scale detainee releases of the type frequently promised by the Government of Syria are likely impossible, since many have died in detention, a reality alluded to by a senior Government security official when seeking to deflect criticism regarding Dar’a detainees in June 2019 (see: Syria Update 27 June-3 July 2019).

Detention has long been a tool of repression and control in Syria. In October 2019, the Syrian Network for Human Rights published a report detailing the scope and scale of detentions in the country, which showed that the Government of Syria is by far the worst offender. A more recent report by Human Rights Watch notes that approximately 15,000 people have died since 2011 due to torture at the hands of the Syrian Government, while nearly 100,000 people have been forcibly disappeared. The COVID-19 pandemic has added an additional layer of danger for detainees who are frequently held inside cramped facilities with poor or non-existent sanitation, and limited or no access to medical care.

Returns, documentation, and accountability

Detention should be an area of focus for donors and analysts, as it has important and far-reaching implications. Refugee returns will be influenced by the patterns of detention, given that many Syrians abroad are wanted by the Government for opposition-related activities. The failed releases, coupled with the pervasiveness of the state security services, magnify protection concerns and disincentivise return. Detention is directly relevant for donor-funded aid activities in multiple sectors. Without documentation certifying the death of their family member(s), Syrians may be unable to claim benefits, access state entitlements, or execute housing, land, and property (HLP) transactions. Detention will also affect overall social stability. The importance of closure should not be overlooked, particularly as donors increasingly emphasise inter-communal reconciliation initiatives and pursue accountability and justice.

Large-scale releases are decidedly unlikely for the foreseeable future, yet there may yet be a glimmer of hope for some detainees and their families. Reports have recently emerged concerning two detainees who were freed after 10 years of imprisonment by the Government of Syria. They had been detained at the ages of four and 10 due to their father’s association with the nascent opposition. That such an event can be examined for signs of hope is a testament to the brutality of the Syria crisis and the pervasiveness of detention.

Whole of Syria Review

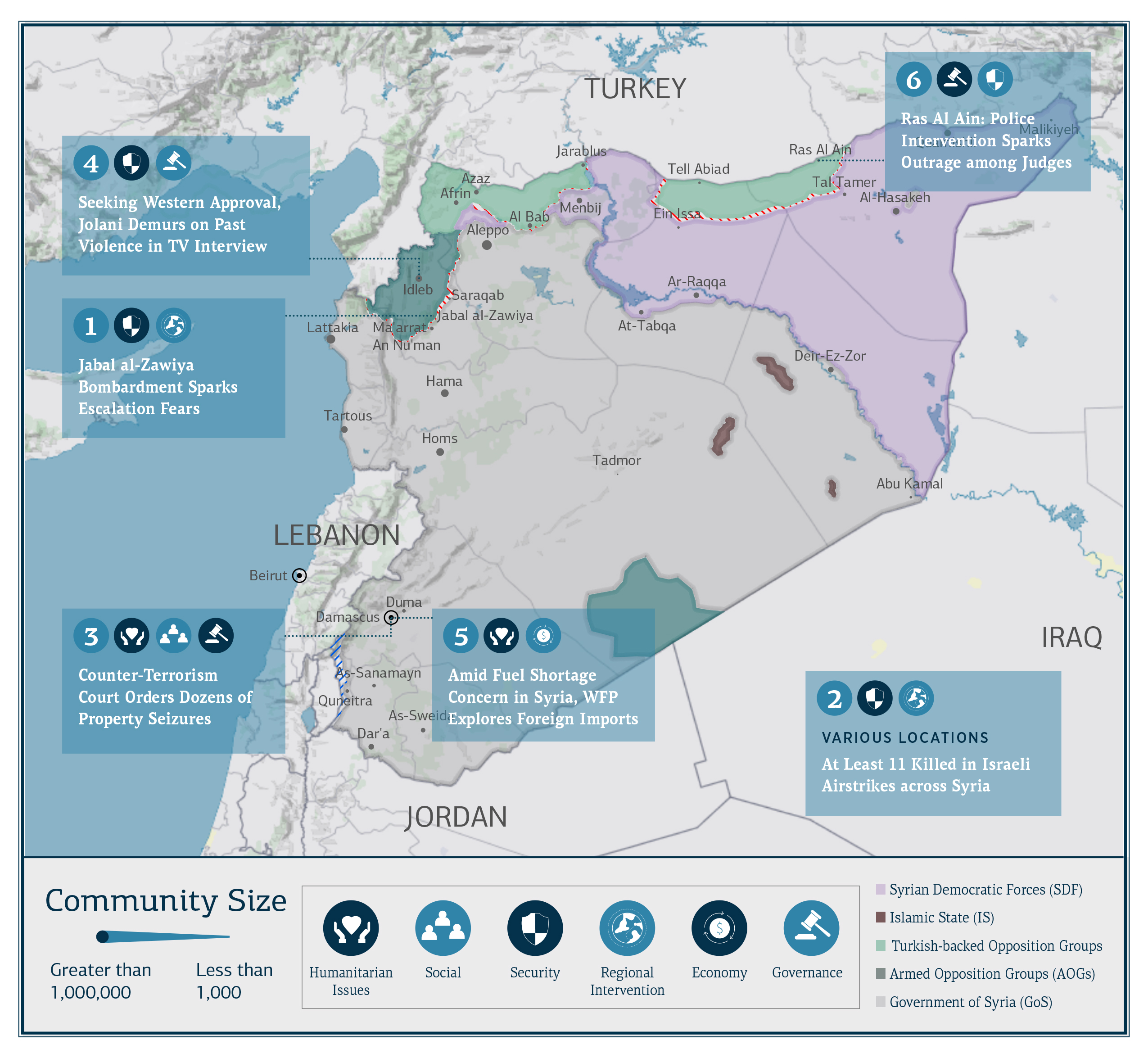

Jabal al-Zawiya Bombardment Sparks Escalation Fears

Jabal al-Zawiya: On 10 June, media and local sources reported that Russian warplanes carried out more than 12 airstrikes in Jabal al-Zawiya in the southern countryside of Idleb Governorate. In addition, Syrian Governفment forces targeted southern and eastern Idleb Governorate with over 150 mortar shells and heavy artillery. At least 12 people were reported killed, four of whom civilians. The Turkish army and opposition forces that are positioned throughout frontlines with the Syrian Government in Idelb responded to the attacks with artillery shelling of Syrian Government sites in southern Idleb. Turkish and Russian delegations met to discuss the situation in northwestern Syria on 8 June.

A warning shot

The airstrikes and shelling in Idleb indicate the tenuousness of the ceasefire agreement in northwestern Syria, but they are more likely to be a limited attack and not the opening salvos of a large-scale offensive, which many in the opposition and in the aid sector now fear. The incidents affirm analysts’ concern that the recent presidential elections would embolden the Syrian Government to take more aggressive actions, but the targeting of Jabal al-Zawiya, a persistent trouble spot, suggests the scope of its current ambitions in the area is limited (see: Syria Update 7 June 2021). Meanwhile, humanitarian sector actors are anxiously awaiting the vote, scheduled for July, on the UN Security Council resolution to extend the mandate for UN cross-border aid operations via Bab al-Hawa. Damascus and its allies seek to end the mandate and force humanitarian actors to reroute aid through Damascus. The intermittent surges in military activity in northwestern Syria are signals by the Syrian Government that the military option remains on the table, which may present a major hurdle to future humanitarian operations in northwestern Syria, irrespective of the outcome of voting in New York.

At Least 11 Killed in Israeli Airstrikes across Syria

Various locations: On 9 June, local and media sources reported Israeli airstrikes targeting Iran-linked sites in Damascus and Homs governorates. Media outlets reported that among the targets were weapons depots near Damascus Airport belonging to Iranian militias and a Hezbollah military site near Ma’rat Sednaya, in the western Qalamoun. Explosions in Lattakia Governorate were reportedly due not to Israeli strikes, but to Syria’s own air defence systems. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights reported that 11 fighters affiliated with the Government, including four members of the National Defence Forces, were killed in southern and western Homs Governorate. At the time of writing, casualty figures for other areas are not available.

No change to Israel’s Iran strategy

The coordinated attack is drawn straight from Israel’s playbook for its shadow war with Iran in Syria. The first since the helicopter attack in Quneitra over a month ago, they come in the wake of significant political upheaval in Israel that has been exacerbated by the war in Gaza (see: Syria Update 17 May 2021). That these attacks have been carried out despite the political upset in Israel evidences the continuity of Israel’s military objectives for the region, irrespective of shifting political coalitions. For the Israeli military and political establishment, the interest in harassing Iranian military sites and confronting Tehran throughout Syria abide. Such strikes can be expected to continue for the foreseeable future, particularly as Iran ramps up its presence in new parts of the country (see: Syria Update 31 May 2021).

Counter-Terrorism Court Orders Dozens of Property Seizures

Damascus: On 7 June, local media reported that Syria’s Counter-Terrorism Court, a military tribunal formed in 2012, ordered the seizure of properties belonging to more than 30 wanted and displaced persons from Eastern Ghouta. Syria’s Military Intelligence service reportedly identified commercial properties and agricultural lands in Arbin and Zamalka for expropriation under the country’s anti-terrorism law. Farmers will be allowed to complete the crop season before the confiscations go into effect. The seizure order follows a similar 5 June decision by the Counter-Terrorism Court to confiscate the property of more than 20 people from Yalda in southern Damascus, following a site visit conducted by Air Intelligence and Military Intelligence Directorates. Those targeted in the 5 June seizure include detainees and others who were forcibly evacuated to northern Syria.

Damascus claims former rebel real estate

Expropriating financial assets and property is among the Syrian Government’s primary methods of suppressing its opponents, although there have been fewer instances of such seizures in recent months. The recent uptick may augur a renewed drive to confiscate assets in former opposition strongholds using the extensive powers afforded by Syria’s anti-terrorism legislation. Since 2011, the Syrian Government has issued several laws and decrees concerning property, real estate, and housing rights. While laws that diminish property rights in favour of facilitating reconstruction projects have received the most attention abroad, anti-terrorism legislation has arguably been used more frequently and to greater effect. These laws have been fundamental in arbitrary legal cases in which resistance to the Syrian state has been conflated with terrorism, leading to the confiscation of the assets and property of opponents and activists, particularly for instance in reconciliation areas in Eastern Ghouta, Wadi Barada, Dar’a, and Quneitra. The Syrian Government’s continued seizure of private property and its impingement of civil rights highlight its unwillingness to change, even as overt armed resistance to Damascus has subsided. Such measures will likely deter many Syrians abroad from returning. Those who fear prosecution under arbitrary anti-terrorism laws will have little hope of legal recourse in Syria. Meanwhile, those whose property or assets have been confiscated will have little to return to.

Seeking Western Approval, Jolani Demurs on Past Violence in TV Interview

Idleb: On 1 June, PBS, an American public broadcaster, aired a long-awaited interview with Abu Mohammad al-Jolani, the leader of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). The interview, conducted in early February by American journalist Martin Smith, was Jolani’s first with a Western journalist. Throughout the discussion, Jolani reiterated that HTS’s primary objective is to wage “a war to liberate a people from a tyrant,” and emphasised that the group does not seek conflict with the West: “This region [HTS-controlled northern Syria] does not represent a threat to the security of Europe and America. This region is not a stage for executing external operations.” Thus, Jolani continued his long-running campaign to reduce pressure from Western security and intelligence authorities, contending that HTS’s designation as a terrorist organisation by the US and other Western states is an “unfair characterisation and a political label with no truth or credibility.” Throughout the interview, Jolani also sought to downplay his linkages to Al-Qaeda and Islamic State (IS).

The wide-ranging interview touched on numerous subjects, including:

- The September 11 Attacks: In Jolani’s view, an act of violent retribution that is understandable if “we can analyse and understand how the events of the past 20 years got us to where we are now.”

- Islamic State: An important Islamist force that hijacked and jeopardised the Syrian revolution.

- HTS’s Battles against various Free Syrian Army factions in 2017: “They were merely gangsters, thieves and bandits.”

- The Salvation Government: A civil society project responding to “the need to have institutions, governance, and administration.”

- Christians in Idleb: “They should have the freedom to worship God in the way they see fit.”

- On credible reports of torture and abuse in HTS prisons: “We do not have prisons.”

Can a leopard change its spots?

The steady drip of information in recent months concerning the interview has built considerable anticipation. Close observers of the situation in Syria will be disappointed, as the interview reveals little new information apart from biographical details about Jolani’s life. (For example, that his father was an Arab nationalist inspired by Nasser who joined the Palestinian fedayeen before becoming an oil expert, and that his family was displaced from Golan by the Israeli occupation.) Jolani made multiple reassurances throughout the interview that HTS is pursuing a strategy that does not pose a threat to the West, and focuses exclusively on resisting the Syrian Government. For some audiences, particularly in the West, these and other claims made by Jolani are unlikely to be convincing. Jolani variously struggled to justify his previous affiliations with al-Qaeda and IS, as well as HTS’s track record of detaining and torturing prisoners, to say nothing of its abuses against religious minorities.

For all its shortcomings, the interview may be an important signal for Syria crisis response actors, who are forced to contend with HTS in key programming areas in Idleb. Jolani’s trajectory from al-Qaeda fighter in Iraq to IS partner has culminated in his leadership of what is arguably the most cohesive and significant armed opposition force in Syria: HTS. HTS’s relevance — and attendant risk to implementers — will grow when the cross-border mechanism is phased out. Without UN operational and logistical support, local implementing partners will be forced to take on a greater role in securing access. Meanwhile, the increase in aid transported by NGOs or private vendors will pose distinct logistical challenges wherever they come into contact with HTS. Defining realistic positions and spelling out mechanisms to secure access in a post-cross-border environment will be a key challenge for aid organisations, which should seek leverage wherever it can be found. Jolani has asserted that HTS and the Salvation Government are responsive, locally legitimate security and administrative actors. A consequential test of their willingness to prove these claims will be seen in their willingness to tolerate an unfettered aid response.

Amid Fuel Shortage Concern in Syria, WFP Explores Foreign Imports

Damascus: During a 9 May meeting held in Damascus and attended by several UN Agencies, Funds, and Programmes (AFPs) and INGOs, the World Food Programme (WFP) disclosed that it had requested permission from the Syrian Ministry of Petroleum and Mineral Resources to explore fuel import options from Jordan and Lebanon (by sea) due to domestic shortages in Syria. According to the meeting minutes, which were first published by Syria Report, this importation of fuel would be a “contingency and a measure of last resort in the event of in-country unavailability.”

Ramifications up the value chain

Although WFP has emphasised in previous reports that external procurement is a normal procedure, it is important to explore its possible ramifications on WFP’s operations in Syria and on the local economy, especially if chronic shortages of fuel or other goods make such procurement methods more common. Currently, WFP maintains strategic reserves of diesel and petrol, which it generally purchases from the Syrian Company for the Storage and Distribution of Petroleum Products (SADCOP), in Damascus, Safita (Tartous), and Quamishli. The fuel is primarily distributed to UN AFP facilities, convoys, and vehicles. It is also distributed to other organisations participating in the WFP-headed Logistics Cluster, and to IDP shelters for cooking and heating (part of the UN’s annual Joint Winterization Programme).

In the case of fuel shortages in Syria, or when purchase from SADCOP is not possible, WFP is authorised to import fuel into the country. Due to the financial crisis and shortage of basic goods in Syria, international aid agencies have become a major source of foreign currency and a major player in local markets. This is true of fuel markets, too. According to UN statistical reports on UN procurements, UN AFPs purchased 7 million USD of fuel from SADCOP between 2011 and 2019. Additional purchases by other actors in the aid sector are difficult to quantify, but are assumed to be considerable. It is not immediately clear what the impacts of a shift toward foreign procurement of fuel would entail for value chains. However, factors such as crossing fees, import costs, and duties will shape the processes and determine whether (and how much) of a reconfigured procurement process would be captured by the Government of Syria. It is worth noting that if WFP looks abroad for fuel, it would likely be perceived as a direct challenge to the state’s historical monopoly. While Syria does face recurring fuel shortages due to limited refining capacity, it is unlikely willing to relent on its role as the sole provider of basic services in the country. Any move in that direction may be seen as a challenge to its legitimacy — and its finances.

Ras Al Ain: Police Intervention Sparks Outrage among Judges

Ras Al Ain, al-Hasakeh: On 8 June, judges in Turkish-controlled Ras Al Ain announced the suspension of the local court due to serial interference in civic affairs and exploitation of the civilian population by local police. The court’s cited several instances of police violations, including: Issuing fines, fees, and confiscation decisions without coordinating with local judicial institutions; arresting civilians and raiding homes without obtaining warrants; and refusing to cooperate with the court or to heed its requests. The suspension follows recent incidents that may have triggered the court’s decision, most notably, a 6 June incident in which a civilian was killed in Mahmudiyeh by police.

The struggle to enforce the rule of law

The Ras Al Ain court was established by the Syrian Interim Government’s Ministry of Justice in March 2020, following Operation Peace Spring (the Turkish-led offensive in al-Hasakeh Governorate). The court’s closure in protest of violations is a sign of the tenuous relations between civilians in Ras Al Ain and the administrative and security authorities that are supported by Turkey. Similar concerns motivated the establishment of the Grievances Redress Committee by the Syrian National Army (SNA) in December 2020, which was meant to improve the relationship between civilians and military authorities in Ras Al Ain, including by addressing infractions (including HLP violations and arbitrary arrests) committed by military and security actors. Zooming out, two important factors jeopardise efforts to foster community acceptance in the Peace Spring area. First, armed factions belonging to the SNA wield considerable influence in the area, and in addition to violations by the police force itself, the SNA-led military police often encroach as well. Second, the governance system in Turkish-controlled areas of northern Syria is fragmented. Because the relationship to corresponding Turkish authorities is paramount, it undermines horizontal cooperation between local governance structures, while emphasising vertical relationships between local actors and the Turkish authorities. Violations like those motivating the court’s suspension are likely to persist as long as these structural drivers of instability remain unaddressed.

Open-Source Annex

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below..

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

Syrians Are Going Hungry. Will the West Act?

What Does It Say? Food security in Syria is now among the foremost issues that will shape the state of Syria for the foreseeable future.

Reading Between The Lines: The detailed and thoughtful piece makes a compelling argument in favour of prioritising efforts to support agricultural livelihoods and food security in Syria.

Five years of Russian aid in Syria proves Moscow is an unreliable partner

What Does It Say? Russia’s humanitarian interventions in Syria have been shallow and inconsistent, making it an unreliable partner for the Syrian Government.

Reading Between The Lines: While all aid work is influenced to some extent by political considerations, Russia’s humanitarian assistance to Syria is especially politicised. Rather than being needs-based and carried out with a firm commitment to humanitarian principles, it is a tool to whitewash Moscow’s image (abroad and among Syrians). That Moscow has failed to intervene in a way that genuinely props up Damacsus’s rule is further evidence of its limited interest in investing more than it has in the Assad regime, now that its basic survival is all but guaranteed.

The Disappearing Plight of Syrian Christians

What Does It Say? Syrian Christians continue their steady exodus from Syria. Where Christians once represented around 30 percent of Syria’s population, it is now estimated that they number less than 700,000.

Reading Between The Lines: Bashar al-Assad was once viewed as a protector of minorities, but this illusion has been shattered, particularly as the Assad regime has manipulated social and sectarian tensions to guarantee its own survival.

‘Times have changed’: Saudi Arabia-Syria in rapprochement talks

What Does It Say? The article contends that Saudi Arabia is close to finalising an agreement on political and diplomatic normalisation with Syria, in the hope of minimising Iran’s influence in the country.

Reading Between The Lines: Saudi Arabia is determined to stanch the spread of Iranian influence in the region, but the evidence brought to light in favor of Riyadh’s impending normalisation with Damascus has so far been flimsy, conspiratorial, and unconvincing.

The Limits on China’s Role in Syria

What Does It Say? Although China supports the Government of Syria and has recognised its most recent presidential election as legitimate, there are limits to the amount of support it can provide.

Reading Between The Lines: Chinese investment in the Arab world is no longer on the rise. Syria has been beset by sanctions that will likely deter Chinese investors. Furthermore, conflict is still a material possibility, and China has shown itself to be averse to major investment in areas racked by conflict, political entanglement, and unpredictability.