In-Depth Analysis

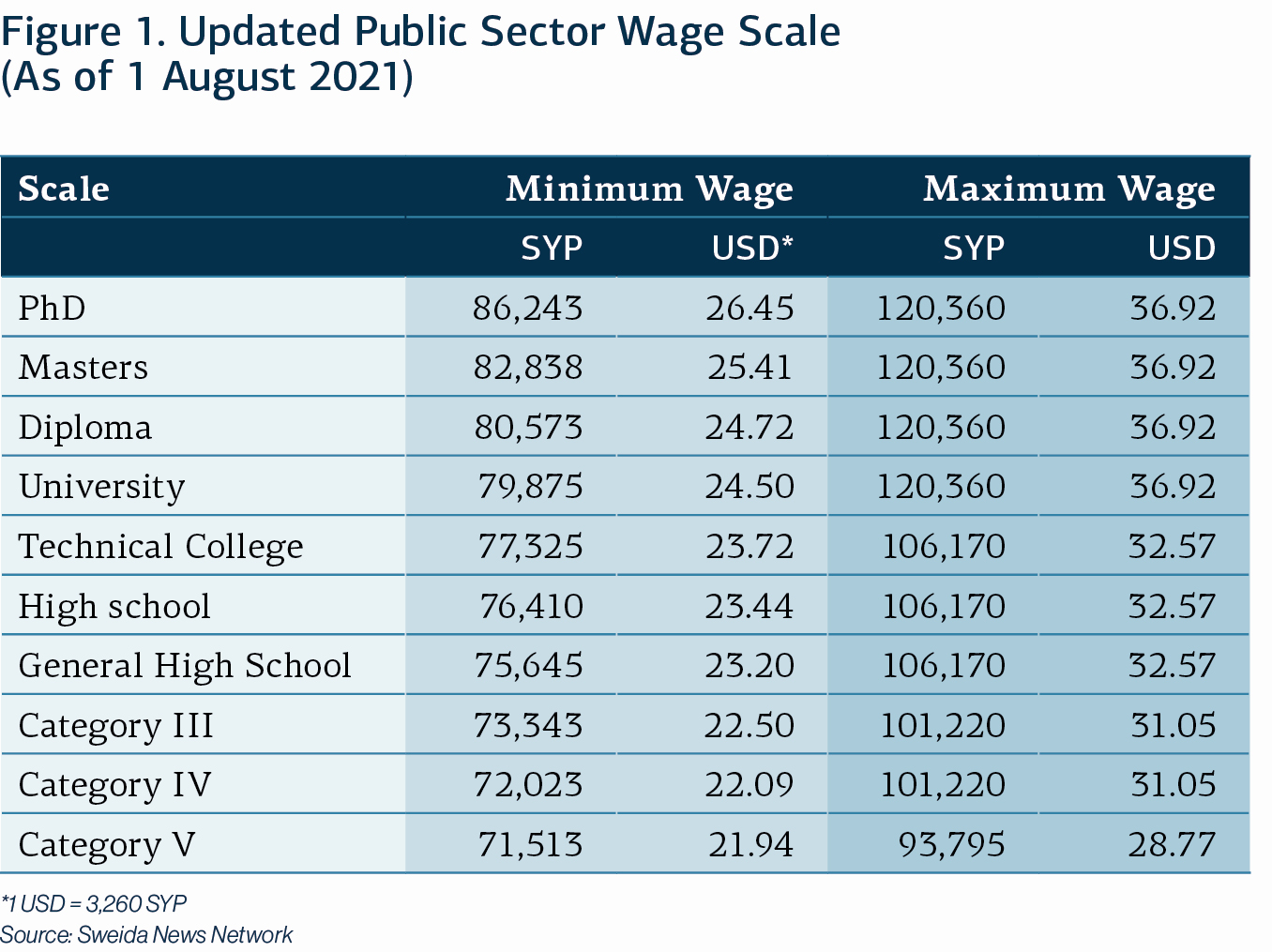

Inflation fears are high one week after the Government of Syria announced a 50 percent salary increase for public workers. The pay raise was announced on 11 July and will take effect in August (see: Syria Update 12 July 2021). The pay bump is a belated, partial response to the demands of workers whose purchasing power has been eviscerated by the currency depreciation that has mired roughly 90 percent of the population in poverty. However, the salary increase (figure 1) also fuels concern that the additional payroll costs borne by the state — estimated at 980 billion SYP annually (approx. 300 million USD, at market rates) — will ultimately be passed on to ordinary Syrians. Indeed, there are signs this is already happening. The rise in state salaries is the sixth since the conflict began, and lessons from previous salary adjustments remain relevant (see: The Syrian Economy at War Labor Pains Amid the Blurring of the Public and Private Sectors). Crisis response actors must note that the relief brought on by the salary increase will be temporary; over time, the interrelated challenges of inflation and currency depreciation will steadily erode Syrians’ economic standing. Aid activities, particularly in price-sensitive areas such as staff salaries and cash for work, must remain flexible to avoid foreseeable pitfalls as Syria’s volatile economy continues to swing.

The new salary scale puts more money in the pockets of state employees, but salaries have shrunk dramatically in recent years. Salaries for PhD-holders now begin at 86,243 SYP per month, which equates to a mere 26.45 USD. Following wage scale adjustments in January 2016, employees in the same salary bracket took home the equivalent of 50.57 USD per month. The result of currency depreciation, this decline is mirrored across sectors and income brackets, and it has considerable impact. Even in relatively affluent Damascus neighbourhoods such as Rukn al-Din, more than one-third of households now rely on humanitarian assistance, according to a survey by the Operations & Policy Center. There is a perverse irony in the fact that Syrian workers self-report some of the longest working hours in the world, yet 94.1 percent have monthly spending that places them beneath the global poverty line, by some measures. The family of President Bashar al-Assad recently staged a public relations outing around a trip to a famous Damascene shawarma shop. A state employee earning the public sector minimum wage would spend one-fifth of his monthly salary to treat a family of five to the same meal.

Although the metrics of Syria’s profound economic deterioration are by now familiar to those who follow the protracted crisis, aid actors and political decision-makers must not become complacent in the face of Syria’s worrying “new normal”. The loss of opportunities in Syria will compound the risk of flight for all Syrians, including skilled technicians whose training was the product of past donor-funded activities (see: What Remains?: A Postmortem Analysis of the Cross-Border Response in Dar’a). Moreover, the shrinking of economic opportunities inside Syria will increase the attractiveness of the war economy, including the narcotics trade and military recruitment by local armed groups and foreign powers who view Syrian fighters as budget-friendly mercenaries for conflicts in Libya and elsewhere (see: The Syrian Economy at War: Captagon, Hashish, and the Syrian Narco-State and The Syrian Economy at War: Armed Group Mobilization as Livelihood and Protection Strategy).

In all cases, the salary scale adjustments can be seen as a shell game played by Damascus to mask the shrinking extent of its support to ordinary citizens. Syrian Minister of Finance Kinan Yaghi told state media that the salary increases will be paid for by the “public resources of the state.” Precisely what this means is unclear. That ordinary Syrians will ultimately bear the costs is not in serious doubt. While the Central Bank of Syria has previously sworn off inflationary steps such as printing money, this option cannot be ruled out. In the meantime, the state continues to reduce the subsidies that are a vital lifeline to struggling Syrians. The pay rise followed only days after the Ministry of Domestic Trade and Consumer Protection raised the litre price of fuel by 20 percent (see: Syria Update 12 July 2021). Dairy prices have already jumped as a result, and other goods and transport-dependent sectors can expect similar price shocks. More cuts to state price support likely lie ahead. On 17 July, Syrian media reported that the Syrian Company for the Storage and Distribution of Petroleum Resources has carried out a study on the impact of halving, to 50 litres, the allocations for subsidised petrol. If the reduction does go into effect, consumers will be forced to make up the difference by resorting to more expensive unsubsidised fuel. The Ministry of Electricity is also reportedly studying long-term energy security, as power cuts continue to paralyse the country. Without the reasonable prospect of energy-sector rehabilitation, future cuts are likely, and they will have a double impact, hampering economic activity and driving individuals to more expensive generators — or forcing them to endure without power at all.

Amplifying concern over the near-term direction of Syria’s economy is the sharp drop in the value of the Lebanese lira, which has lost nearly 30 percent of its value since the beginning of July. The two currencies — like the economies they underpin — are deeply interconnected. No factors have had a more dramatic negative impact on Syria’s economy than the banking and currency crises that beset Lebanon in late 2019 (see: Two Countries, One Crisis: The Impact of Lebanon’s Upheaval on Syria). On 15 July, the lira entered a deep slump following the announcement by former Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri that he will walk away from his mandate to form a new government, following nine months of fitful attempts to do so. At the time of writing, the Lebanese lira (LBP) trades at roughly 22,000 LBP/USD.

Dead reckoning

Navigating aid work in Syria amidst currency depreciation and economic volatility will require frequent course-corrections, including by understanding the Government of Syria’s own wage practices. As currency depreciation has accelerated, the Syrian Government has relied on a series of one-time payouts to cover the spread between wages and rising market prices. Doing so has allowed it to defer making more frequent adjustments to wage scales, which would erode confidence in the currency. Traditionally, aid implementers determine their local staff wages and the compensation for cash-for-work programmes in accordance with the public-sector scale to avoid distorting the labour market. They should follow changes to Syrian Government pay scales closely, but pegging wages to these scales is not enough. Achieving parity and avoiding causing unintentional harm to beneficiaries and staff will require a more nuanced approach that also accounts for periodic bonuses and one-time payments that the Syrian state has offered. In the long term, aid actors must also consider ways of compensating staff that will avoid two paramount harms: upsetting the labour market and paying poverty wages merely because Syria’s largest employer, the state, also does so.

Whole of Syria Review

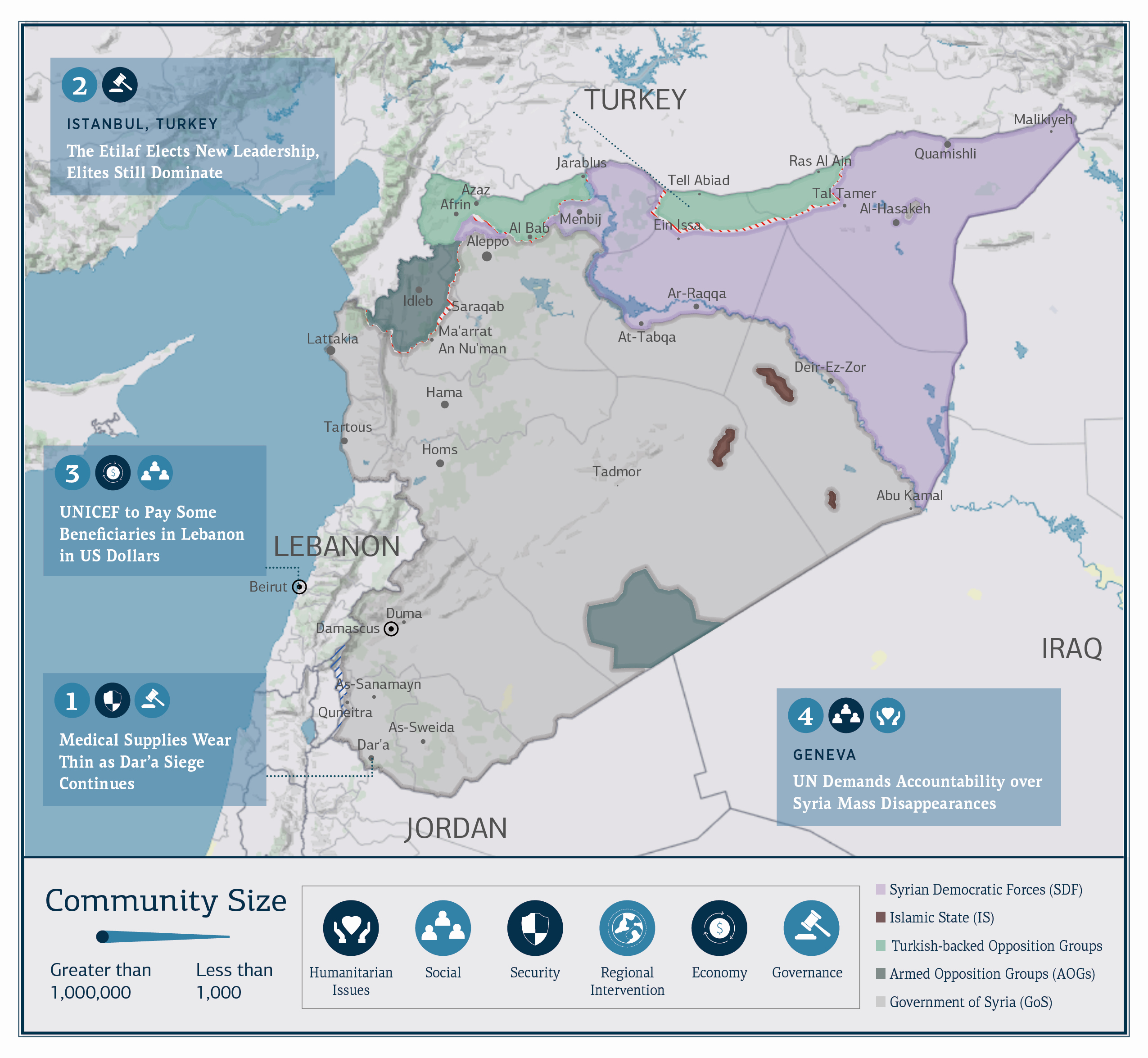

Medical Supplies Wear Thin as Dar’a Siege goes on

Dar’a al-Balad, Dar’a Governorate: On 16 July, a World Food Programme (WFP) convoy implemented by the Syrian Arab Red Crescent (SARC) reached Dar’a al-Balad, marking the first major aid distribution to the area since the siege of the community began on 24 June (see: Syria Update 5 July 2021). Aid deliveries to Dar’a al-Balad stopped at the siege’s onset. Local sources indicate that as of 11 July, previous attempts to reach the besieged population had failed in part because SARC refused to enter the community. SARC-affiliated actors had reportedly advised residents to leave Dar’a al-Balad and seek aid in other areas. Although SARC did not publish an official statement concerning access or its distributions in Dar’a, local sources indicate that the organisation aired concerns about the security situation, and expressed a fear of being subject to attacks due to its close relationship with the Syrian Government. Although the food aid delivered on 16 July brings much-needed relief, medical supplies are running dangerously low, and their prices have more than doubled. Pharmacies and medical centres are experiencing severe shortages, and lack key supplies such as diabetes medication and equipment needed to perform caesarean sections.

Sayf al-Dawla: Humanitarian aid

The Syrian Government has routinely and strategically weaponised humanitarian aid to achieve its conflict aims. Although WFP was able to deliver food baskets to Dar’a, medical supplies are dangerously low, and siege conditions remain in place. While details concerning the siege and aid access remain hazy, the ongoing siege of Dar’a is arguably among the most high-profile blockages of aid access in Syria since 2018. The siege ostensibly began as a response to the community’s refusal to hand over 200 light weapons. However, the root cause of the siege was Dar’a’s continuing quasi-independence, exemplified by its refusal to participate in the Syrian presidential election in May (see: Syria Update 5 July 2021). Pressuring Dar’a al-Balad to capitulate sends a powerful message to other communities that harbour latent opposition sympathies. That said, the community continues to hold out, which may indicate that smuggling networks remain a tenuous lifeline. However, these are unlikely to cover all the medical needs of people in the area. As supplies dwindle and impoverished people are faced with skyrocketing prices for smuggled goods, their ability to withstand the siege will be put to the test.

The Etilaf Elects New Leadership, Elites Still Dominate

Istanbul, Turkey: On 12 July, the Etilaf General Committee in Istanbul elected Salem al-Musallat as the new President of the National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces (Etilaf). Al-Musallat won 71 out of 81 votes, and was the sole candidate. Haitham Rahmeh was elected General Secretary, and Ruba Habboush and Abdel Ahad Astifo were voted in as Vice Presidents. A third Vice President will be nominated at a later time by the Kurdish National Council. Al-Musallat is a leader of the Jabbour tribe and is originally from Al-Hasakeh; he is the head of the Syrian Tribes and Clans Council and a former member of the Syrian High Negotiation Committee (SHNC). Al-Musallat succeeds Nasir al-Hariri, who announced last month that he would not run for another term as president amidst unprecedented popular criticism for his leadership of the Etilaf (see: Syria Update 21 June 2021).

Staying the course

Although the election constitutes a shift in the Etilaf’s top-level leadership, it is unlikely to lead to a significant change, with elites continuing to dominate, as they have since the organisation was founded in 2012. During al-Hariri’s term, the Etilaf intensified efforts to expand its presence in Syria through a beefed-up active presence in northern Syria (i.e. conducting meetings with locals and attending funerals), and the opening of a new branch in Azaz. Such activities were perceived as a step toward realising al-Hariri’s vision of solidifying the Etilaf’s social constituency inside Syria; however, al-Hariri’s popularity suffered a major setback during the final months of his term due to increasing criticism of the Etilaf’s overall political performance. While the Etilaf has a vital role in representing the Syrian opposition on the international level, for example through the SHNC, and on the level of local governance through the Syrian Interim Government, it has shown a limited capacity and willingness to engage Syrian people and local community representatives in these processes. The election of a tribal figure from Al-Hasakeh may indicate an attempt by Turkey to co-opt the Etilaf as a tool to reach out to tribes in Syrian Democratic Forces-controlled areas of northeast Syria, a region Turkey has long been keen to destabilise.

UNICEF to Pay Some Beneficiaries in Lebanon in US Dollars

Beirut, Lebanon: A new UNICEF project launched last week will provide aid support in US dollars to 70,000 Lebanese, Syrian, and Palestinian families in Lebanon. Most aid is currently distributed in Lebanese lira (LBP) and converted at exchange rates set by Lebanese banks, generally ranging from 1,500 to 6,240 LBP/1 USD, while the market rate of exchange reached 22,000 LBP/USD late last week. The news followed an investigation which found that Lebanese banks had captured at least 250 million USD in United Nations aid since the start of the economic crisis in late 2019, through the manipulation of exchange rates.

Individualised decisions, collective risks

The decision marks a new phase in an ongoing debate among aid actors in Lebanon and Syria since the onset of interlinked economic crises in late 2019. There is debate among aid actors over the merits of offering assistance in USD or Lebanese lira. USD-based transactions greatly increase the purchasing power of beneficiaries and avoid the aid diversion resulting from restrictive capital controls that handcuff the Lebanese financial sector. While the use — and therefore, stability — of the lira is important for maintaining some degree of confidence in the local currency, its use allows banks to siphon significant portions of the value of incoming assistance. More than a year into this debate, aid actors have yet to come to a unified decision, pushing individual NGOs and UN bodies to choose their own course of action on an ad-hoc basis. While different activities and objectives may benefit from differing ways of working, there is a risk to a scattershot, uncoordinated approach. This area is particularly sensitive at a time when relations between Syrian refugee and Lebanese communities remain fraught. Inconsistent modalities of cash assistance create further economic disparities within a crisis that has already deeply impacted the majority of those living in Lebanon. The variation in distribution techniques across the aid sector will likewise create confusion and frustration among beneficiaries receiving aid in LBP, threatening NGOs’ credibility if they do not effectively communicate the implications of these decisions.

UN Demands Accountability over Syria Mass Disappearances

Geneva: On 13 July, media sources reported that the UN Human Rights Council has called for the parties responsible for “massive scale” forced disappearances during the ten years of conflict in Syria to be held accountable. A draft resolution introduced by the UK, several EU members, the US, Turkey, and Qatar denounced the “consistent patterns of gross violations” in the context of the Syrian conflict. The text underlined concerns about the fate of tens of thousands of people who have vanished in detention, and strongly condemned the continuing use of forced disappearance as a military tactic (see: Syria Update 14 June 2021). It called attention to resulting abuses and efforts to use detention, particularly by the Government of Syria’s security apparatus, “to spread fear, stifle dissent and as punishment.” In addition to the Syrian Government and the Islamic State, the Turkish-backed armed opposition have been directly singled out over accusations of abductions and kidnapping for ransom.

Accountability and the diaspora

Throughout the ten years of conflict in Syria, numerous initiatives, campaigns, and resolutions condemning forced disappearances have emerged, with demands ranging from the publication of information concerning captives to outright release. The lack of progress toward a sustainable resolution to the conflict will impede efforts to make progress on the detainee issue. This is due in part because full disclosure has the explosive potential to cause widespread unrest, as many detainees are feared dead (see: Syria Update 14 June 2021). Without a framework to accommodate disclosure, further denial and prevarication are likely. As donors focus increasing attention on detainee issues, accountability, and inter-communal reconciliation, they will be forced to grapple with these hard truths. There is also a silver lining, however. The detainee issue is one of the few in Syria that is capable of mobilising and unifying Syrian diaspora groups and those inside the country, regardless of their backgrounds and political views. Creating meaningful action that seizes on this reality will be a key issue facing donors going forward.

Open-Source Annex

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below..

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

Munitions Typology: Chemical Weapons Deployed in the Syrian War

What Does It Say? The report contains a data portal and interactive map documenting hundreds of chemical weapons attacks in Syria, identifying weapon types in an effort to identify patterns of use and likely perpetrators.

Reading Between the Lines: The Government of Syria has on many occasions denied the use of chemical weapons, although use patterns derived from across the conflict leave little room to doubt its general culpability, even if individual incidents can sometimes be contested.

Denmark’s policy to return Syrian refugees unleashes anxieties, splinters families

What Does It Say? The report documents how Syrians in Denmark are struggling to find a sense of belonging as pressures to legally impede their presence in Denmark mount.

Reading Between the Lines: Syrians’ feelings of uncertainty in the country are a direct consequence of the Danish government’s policy decisions, which are intended to dissuade Syrians from putting down roots in the country.

European Countries Restore Ties with Assad. Small Steps or Turning Points?

What Does It Say? The report contends that Cyprus and Serbia have begun to normalise relations with the Government of Syria, after Cyprus opened an embassy in Damascus and Serbia sent an ambassador.

Reading Between the Lines: Some Member States have been more forward than others in reckoning with the dawning reality the Government of Syria will be unavoidable in the long term. That said, the actual impact of Member State actions in Damascus are often overstated, particularly as highly vocal opponents of the Syrian Government militate against any engagement.

What Does It Say? Russian jets carried out over 20 airstrikes on Islamic State (IS) positions in the Homs and Ar-Raqqa deserts.

Reading Between the Lines: While the 20 airstrikes are significant, desert attacks are rarely effective and amount to little more than a show of force. As on the other side of the Euphrates River, a concerted, effectual plan to erode IS’s foothold is lacking.

HTS Detains Journalists in Idleb

What Does It Say? Media activist Adham Dashrani was detained in Idleb by Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) for criticising the high fuel prices.

Reading Between the Lines: HTS’s harsh treatment of civilians and repression of dissent have been sources of tension and contributed to their unpopularity. This creates a major challenge to HTS’s long-term bid to match its supremacy with popular legitimacy.

Russia and Turkey engage in talks to restore water supply to a million citizens in AANES

What Does It Say? Russia and Turkey have begun negotiations to reopen the Alok water plant, which provides around 1 million people in the Al-Hasakeh region with water.

Reading Between the Lines: This station has been closed repeatedly over the course of the conflict, and it will likely be shut down again, as it remains a key pressure point and disputes over water resources continue.

The destruction of the energy sector in Syria during the war 2011-2020

What Does it Say? The article reviews the damage and setbacks that the energy, oil, gas, and electricity sector have suffered over 10 years of war in Syria.

Reading Between the Lines: International powers have played a significant role in Syria’s deteriorating energy sector. The Syrian Government does not control Syria’s major oil and gas fields. Along with sanctions and lack of access to the oil and gas fields have led Syrian citizens to suffer from power cuts that can last up to 48 hours.