In-Depth Analysis

On 4 August, Syrian state media reported that one person was killed and three were injured and taken to hospital after an explosion aboard a military bus carrying members of the elite Republican Guard in Damascus. The Syrian Arab News Agency (SANA) claimed that the explosion was the result of a short circuit that ignited the bus’s fuel tank. On the same day, however, al-Qaeda loyalist group Hurras al-Din claimed responsibility for the incident, stating it was a deliberate attack carried out in response to the Government of Syria’s military escalation against their “brothers” in Dar’a, i.e. the reconciled opposition fighters facing heavy military bombardment (see: Syria Update 2 August 2021). Concrete details concerning casualties and damage are not available at the time of writing, yet there is little evidence available to cast doubt on Hurras al-Din’s claim. Attacks inside Damascus are relatively rare, while Hurras al-Din’s presumed culpability has important implications for the trajectory of the extremist groups that remain active in Syria.

Attacks such as these have been rare inside Damascus since Government of Syria forces recaptured the surrounding countryside from a constellation of armed opposition factions in 2018. Although the extent of the damage is disputed, the event signals that even priority areas secured by Government forces are not free from the risk of attacks carried out by actors opposed to President Bashar al-Assad. To date, supporters of Hurras al-Din and the Government of Syria have circulated competing narratives concerning casualties and the military rank of those targeted. The most bullish reports indicate that as many as 18 people were seriously wounded, but these claims are difficult to substantiate. However, the event’s impact is tied more to its location than its extent. The explosion occurred in Masaken al-Haras, an area that is predominantly populated by Alawite members of Syria’s military and security establishment and their families, and known for its tight security.

In the main, the attack is a bid for relevance by Hurras al-Din, which has sought to distinguish itself since its longstanding rival, the extremist group Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), became the undisputed local power throughout most of northwest Syria in early 2019. Since June 2020, HTS has intensified its crackdown on Hurras al-Din by dismantling its military bases in Idleb and killing and detaining its members and senior leadership. By succeeding in killing and wounding Government security forces in Damascus, the latest attack allows Hurras al-Din to undercut HTS’s claim that it alone is the torchbearer of the Syrian uprising and the country’s Sunni Muslim majority. HTS is now engaged in a sweeping campaign for acceptance as a rational, status-quo regional power in Syria (see: Syria Update 14 June 2021). The more decisively HTS attempts to whitewash its image as it pushes for tacit acceptance in the West, the more likely Hurras al-Din will be able to differentiate itself and capitalise on symbolic attacks to burnish its revolutionary (and extremist) credentials.

Hurras al-Din’s reference to its “brothers” in Dar’a should not be over-interpreted. Dar’a al-Balad has been under partial siege and bombardment with only brief reprieve since late June, and recent escalation by the Government of Syria has ignited violent resistance in surrounding communities throughout the southern Syrian countryside. Social media accounts within insular extremist and pro-uprising circles have contrasted HTS’s insipid response to the events in Dar’a with the flesh-and-blood consequences of the Damascus attack. However, the actual linkages between the group and southern Syria are modest at best, and the attack has little apparent connection to escalating military pressure in the south. Notably, Hurras al-Din also carried out a surprise attack targeting Russian forces in Ar-Raqqa Governorate in January. In a similar vein, the earlier attack indicated that the group’s ambitions reached beyond its narrow toehold in isolated pockets of northwest Syria, but it provided little indication of focused strategic ambitions (see: Syria Update 11 January 2021).

‘Fortress Damascus’?

The latest Hurras al-Din attack dents the perception of Damascus as unassailable. This will have potential implications for mobility and checkpoints beyond the immediate area of the attack. The removal of checkpoints and the low incidence of deadly security incidents in the capital are major indicators that foreign governments have pointed to as evidence that Damascus is “safe” for the return of Syrian refugees (see: Point of No Return? Recommendations for Asylum and Refugee Issues Between Denmark and Damascus). Such claims should be continually re-examined. Moreover, implications may range wider than the capital. Given the pressure it faces in Idleb, Hurras al-Din is likely to view operations in other regions of Syria as being less directly antagonistic toward its chief rival, HTS. The group may still play a spoiler role across Syria, even if its capacity to carry out coordinated, large-scale attacks in the future is hampered by its modest resource base, competition with HTS, and limited human and financial capacity.

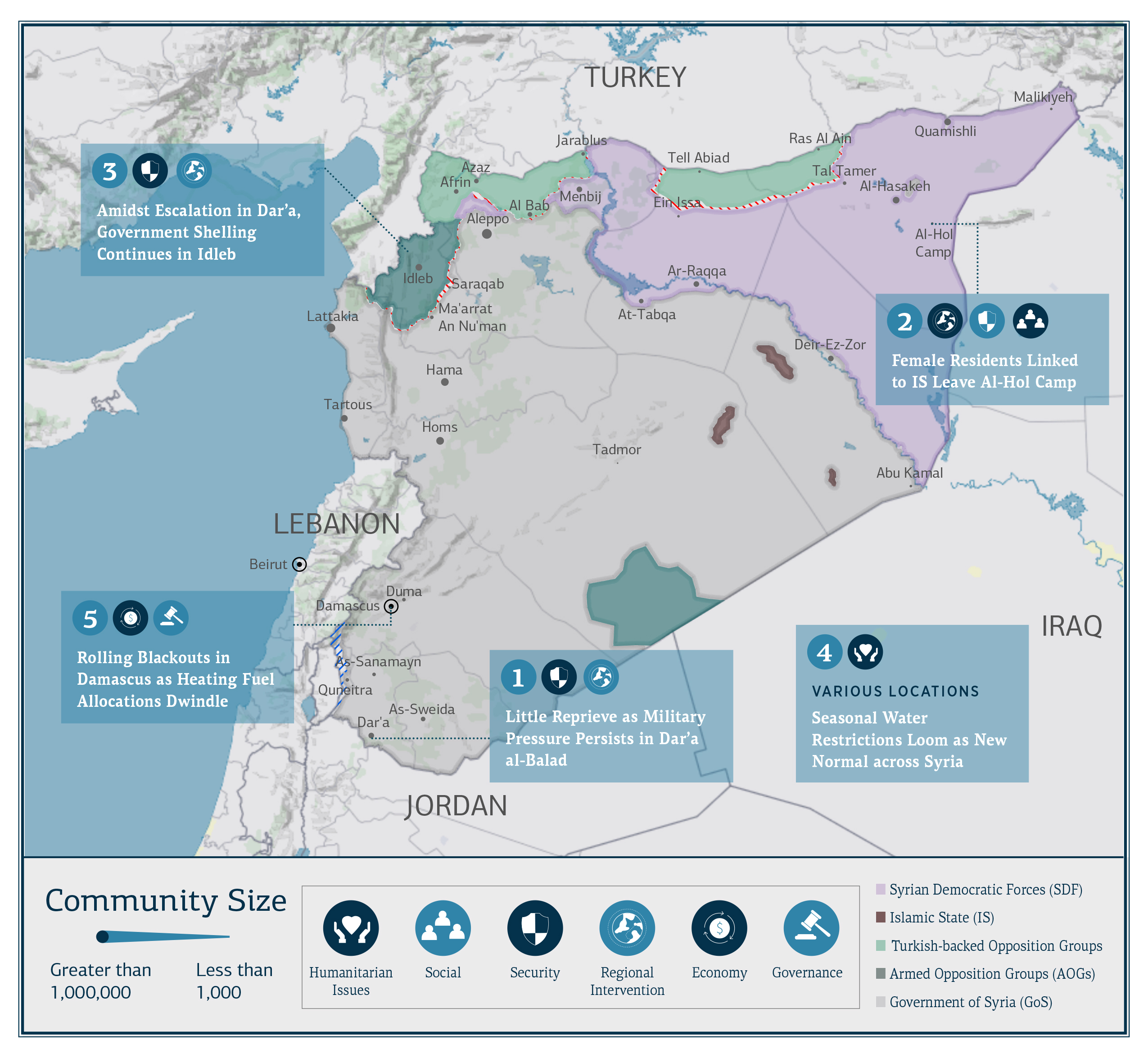

Whole of Syria Review

Little Reprieve as Military Pressure Persists in Dar’a al-Balad

Dar’a al-Balad: On 5 August, Dar’a tribal leaders and notables issued a statement once again calling on Damascus to halt the quasi-siege of Dar’a al-Balad, stop the military campaign to pacify Dar’a Governorate, expel Iranian militias from southern Syria, and enforce Russia’s commitments as a guarantor of the reconciliation agreements in Dar’a. This comes after the failure of talks between the Government forces and the Central Negotiations Committee. On 6 August, media sources reported that during a meeting between Russian army officers, local notables, and the Central Negotiations Committee, Moscow pledged to end the military escalation and lift the siege of Dar’a al-Balad as Government forces continued to target Dar’a al-Balad, Tafas, and Mzeireb via artillery bombardments.

In the meantime, residents of Dar’a al-Balad continue to displace in growing numbers to the relative safety of Dar’a al-Mahata, in anticipation of large-scale military operations in the area. According to local sources, the number of displaced people in Dar’a al-Balad exceeded 21,000, including several thousand people sheltering in schools and mosques amid difficult humanitarian conditions. Notably, Government forces have imposed fees on people being displaced from affected areas, thus forcing them to pay for the privilege of avoiding potential bombardment in Dar’a al-Balad. In addition, local and media sources indicated that Government artillery bombardments of Nahta, in eastern Dar’a Governorate, have led to displacement toward As-Sweida Governorate.

Lengthy negotiations, limited options

Although it has promised the Central Negotiations Committee to stop the violence and reach a peace agreement, the Syrian Government continues to prolong the negotiations by refusing to bend on its fundamental demand for complete subordination. In the face of unyielding local resistance, Damascus persists in intimidating the community through siege and the threat of further military operations. For their part, the Central Negotiations Committee and local notables have prioritised steps to spare Dar’a from military bombardment and maintain community cohesion, yet they have failed to propose terms that Damascus is willing to accept. In the long term, the conditions are highly asymmetric, and they skew decidedly in favour of the Government of Syria. Dar’a has the capacity to refuse to come to terms, but it has little to offer in return for softer treatment by central authorities. Making matters worse for the community, Russia continues to offer implicit support for the military pressure being applied to the community, and its ability to step in to fulfill the 2018 reconciliation terms as demanded by local leaders is doubtful. Meanwhile, the humanitarian situation remains challenging. The current displacement is arguably the most significant witnessed in south and central Syria since 2018, and fees extracted from fleeing residents add insult to injury. Aid projects in Dar’a city and the surrounding communities where violence has broken out will likely face intermittent interruption for the foreseeable future, particularly given that there is no end in sight for the unrest in southern Syria.

Female Residents Linked to IS Leave Al-Hol Camp

Al-Hol Camp, Al-Hasakeh Governorate: On 22 July, Kurdish regional media reported that 82 families (229 women and children) who are connected to Islamic State (IS) fighters who had been killed or detained by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) were released. Discharged camp residents demonstrate their innocence and go through an SDF-led vetting procedures before they are cleared for release. The mass release is one of the largest since the SDF’s October 2020 decision to empty al-Hol by easing conditions for the return of camp residents (see: Syria Update 12 October 2020). The event follows the repatriation, in May, of 100 families from the camp to Iraq, the first such repatriation (see: Syria Update 31 May 2021).

Barriers to return

Return from al-Hol is an imperative for preventing the spread of radical ideology among residents, including vulnerable youth. It is also a moral imperative that will be instrumental to justice, intercommunal accountability, and community reconciliation initiatives. While conditions for the return of foreign residents are complex and differ according to the country of origin, the release of Syrian camp residents is also complicated; aid implementers and decision-makers face pressing challenges whether they focus on implementation to ease the conditions facing those inside the camp, or choose to focus on projects designed to stabilise communities whose residents are now held at al-Hol. Dismal conditions in the camp impinge on residents’ basic human rights and dignity (see: Syria Update 8 March 2021). Moreover, security risks routinely result in the killing of inmates. Facing such pressures, former inmates interviewed by COAR note that female residents sometimes marry online suitors or resort to digital fundraising to generate the cash needed to pay to be smuggled out of the camp. As long as political and procedural barriers impede efforts to empty al-Hol, donors should consider initiatives to improve conditions, including access to basic services and health and food aid. Additional efforts should include behavioural and psychosocial support, the provision of child-friendly areas, and education and wellbeing resources.

In the longer term, paving the way for return to communities in Syria will be a necessary step to empty the camp. Barriers to return are daunting, and they include: the unwillingness of some communities to reconcile with former residents affiliated with IS; the perception that returnees from the camp are entitled to special treatment while their own needs go unmet; and ethnic, tribal, and religious sensitivities. Reports are now circulating that some IDPs who have left camps in northeast Syria are applying to return to camps. They are a troubling indicator that although camp conditions are often poor, return movements will not be sustainable unless life in home communities is dignified, safe, and sustainable too.

Amidst Escalation in Dar’a, Government Shelling Continues in Idleb

Idleb: On 6 August, Government of Syria forces and allied militias continued shelling areas in the southern and western Idleb countryside. Media sources reported that Syrian Government forces targeted the homes of civilians in Idleb communities with heavy laser-guided Russian “Krassenbul” artillery shells, causing significant damage to infrastructure and private property. Communities in the Idleb, Aleppo, and Hama countrysides have witnessed several days of continuous, intense artillery and missile bombardment by Government of Syria forces and allied militias, in addition to an ongoing Government-led military campaign in the Jabal al-Zawiya area launched at the beginning of June. One monitoring group documented 65 civilian casualties, including 29 children, 10 women, and five humanitarian workers, and more than 4,361 displacements. The escalation consisted of more than 791 attacks on opposition areas, 19 of which directly targeted medical facilities, refugee camps, and schools, between the start of June and 25 July. On 30 July, the opposition factions operating in Idleb Governorate launched an artillery campaign targeting the positions of the Government forces and allied militias in Idleb’s southern countryside and western Hama, which they claimed was a show of support for Dar’a city. Around the same time, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad vowed to make “liberating those parts of the country that still need to be liberated” one of his top priorities when he took the oath of office for a fourth seven-year term after winning 95 percent of the vote in May’s election.

Destabilisation, disruption, and displacement

The bombardment of Idleb has slowly increased since the presidential election in late May. Turkey and Russia, which back opposing sides on the frontlines in northwest Syria and exercise strong influence over the region’s security and military direction, apparently have yet to hash out a workable agreement to wind down the violence in the region. There have so far been no reports of negotiations to reach a ceasefire. Russia remains intent on seeing Turkey, which maintains a major direct military presence in Idelb, force the opening of crossing points between the opposition and Government of Syria areas, as Moscow has insisted. To date, this remains unlikely due to strong community pressure against it. Meanwhile, there are no compelling indicators that the Government of Syria and Russia will launch a large-scale military campaign to retake Idleb, particularly given their narrower focus on the Jabal al-Zawiya region. For the time being, the most likely scenario is that the region continues along the path set by recent months of relatively steady bombardment that is intended to destabilise and disrupt opposition-held areas and displace the residents of vulnerable frontline communities, but without fundamentally altering the region’s trajectory.

Seasonal Water Restrictions Loom as New Normal across Syria

Various Locations: Obtaining non-potable and drinking water has become increasingly challenging across Syria in 2021, and has been further complicated by a recent summer heat wave. In Tartous, residents report that state water distributions for indoor plumbing have been significantly reduced in recent months. When water does arrive, electricity shortages make pumping difficult, further constricting access (see: Syria Update 2 August 2021). Such developments are particularly challenging for rural residents who rear livestock and for families who have shifted to home gardening to offset rising food prices. Such difficulties are likely to abate, albeit temporarily, as people shift to rainwater and snowfall in winter months.

While the state withdraws from its role in water provision, private water trucks have filled some gaps, but at a hefty price. Private water pumping costs as much as 12,000 Syrian Pounds (SYP) (3.70 USD) on the black market in Damascus. In some areas, such initiatives have been met with red tape: despite reduced capacity to provide water to residents, one municipality in the Homs countryside shut down seven private water trucks for operating without a license. The license costs over 600,000 SYP (around 185 USD) and takes about six months to be approved.

Resource gaps and programmatic risk

The privatisation of water and other basic services reduces access for a growing number of Syrians. Challenges with service provision likewise reflect infrastructural damage sustained during the conflict. Damaged water pumping stations, for instance, are now falling further into disrepair, as the economic crisis has made maintenance more difficult. Such challenges affected Syria’s most marginalised communities as well as aid programmes that are dependent on water, electricity, and fuel. Shortages of these resources have already caused major delays and disruptions in aid projects over the past two years. These dependencies pose particular challenges for agriculture and livestock-focused programmes which rely on access to fuel, water, and other services for continuity. As shortages in key products become increasingly commonplace amidst Syria’s economic crisis, aid practitioners will be pressed to look beyond programmatic risks posed by security developments and direct conflict. Instead, prolonged resource shortages threaten the feasibility and sustainability of future aid interventions.

Rolling Blackouts in Damascus as Heating Fuel Allocations Dwindle

Damascus: On 3 August, media sources reported that two power plants in Rural Damascus, Deir Ali and Tishrine, stopped working due to technical issues and lack of gas, causing a partial blackout in many cities in southern Syria, including Damascus. According to media sources, electricity was available for one out of every six hours. The power outages also interrupted water provision, exacerbating needs during the summer heat. The Minister of Electricity Ghassan al-Zamel stated that restoring the full capacity of both power plants will take several months, as the Russian company that won the maintenance contract must first import the necessary equipment from Russia. Relatedly, on 2 August, the Syrian Ministry of Oil and Mineral Resources announced that the first distribution of heating fuel rations provided via the smart card system will be set at 50 litres per person. If a second distribution of the same volume is made, as in previous years, the yearly total would amount to a fifty percent cut compared to last year’s allocation of 200 litres. This comes less than a month after the price of subsidised heating fuel was raised from 180 to 500 SYP per litre, an increase of 178 percent.

Services stop, suffering goes on

As Syria’s economic collapse continues, multi-sectoral privations such as these will continue to mount. Damage to infrastructure and limited rehabilitation hamper electricity distribution and worsen the power outages that will make navigating hot summer months more difficult, particularly for the already vulnerable. As seen in recent months in Lebanon, fuel shortages can also worsen conditions in other sectors reliant on refrigeration, including food storage. Meanwhile, a winter heating crisis is looming due to the decrease in heating fuel allocations and skyrocketing prices. By reducing the volume of subsidies and increasing the price, the Government of Syria reduces costs to itself, albeit by forcing ordinary Syrians to pay the difference. Perversely, the collapse of the local economy, a decline in livelihood opportunities, and currency depreciation all conspire to limit the financial resources that are needed to fund alternative power sources such as solar panels and communal generators. It is becoming harder for ordinary households to cover their basic needs such as fuel, bread, and water. Anticipating these challenges months and seasons in advance will be a major challenge for the crisis response. In the long term, response actors must identify ways to sustain basic needs without relying solely on repetitive cycles of short-lived forms of support.

Open-Source Annex

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below..

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

Syria’s ‘bread crisis’ in graphs

What Does it Say? The graphics demonstrate how after nearly eleven years of conflict, people across Syria are facing fuel shortages and rising food prices, alongside an inflation rate that has been soaring for nearly two years. But the impact of this economic implosion is not hitting all Syrians equally.

Reading Between the Lines: The financial collapse has hit Syrians across the country in disparate ways, in part because the country is split into three zones of control (Government of Syria areas, the northwest, and the northeast), which have access to different markets, borders, natural resources, and sources of aid.

Opinion: Biden’s Syria strategy is missing in action

What Does it Say? Six months into his administration, President Biden has yet to arrive at a new strategy for addressing the conflict in Syria. The article contends that the situation on the ground is deteriorating as Moscow, Tehran, and the Assad regime take advantage of U.S. hesitation.

Reading Between the Lines: The Biden administration has not completely ignored Syria. The U.S. worked to stop Russia from cutting off the last humanitarian aid corridor to Idleb and, more recently, Secretary of State Antony Blinken announced new sanctions against eight of Syria’s most notorious prisons. However, Syrians expect the Biden Administration to act on its promises to lead new international efforts to protect civilians and advance a real political solution to the conflict rather than limiting itself to piecemeal measures.

Russia recalibrates coordination with new Israeli government in Syria

What Does it Say? The article qualifies reports that the Kremlin is about to revise its approach to Israeli military intervention in Syria. The reported downing in Syria of incoming Israeli missiles in recent weeks has fueled speculation that Moscow will take a harder line against Israel.

Reading Between the Lines: As the article notes, such talk is not entirely new, and Moscow has long pushed to project its images as a military superpower capable of executing military guarantees in support of its Damascus ally. Moreover, the fact that Israeli attacks consistently strike targets linked to Iran — a strategic rival of Russia’s in Syria — reduces the incentive for Moscow to push back against the attacks.

National Army: Sanctions on “Ahrar al-Sharqiya” are unjust

What Does it Say? The opposition Syrian National Army has criticised the U.S. Treasury’s decision to impose sanctions on its Ahrar al-Sharqiya faction and two of its leaders.

Reading Between the Lines: This decision is the first of its kind against a faction under the Syrian National Army. The faction has been repeatedly accused of violations against civilians particularly in the Afrin region. The SDF welcomed the sanctions as a preliminary effort toward justice whereas the SNA condemned it as a political move resulting from YPG/PKK lobbying against the SNA.

Russia’s envoy to the United Nations: Renewing cross-border aid to Syria will not be automatic

What Does it Say? Russia’s envoy to the United Nations made it clear that the entry of aid into Syrian territory across the border will not be automatic after the first six months of the mandate, saying that the renewal will be based on many conditions in the text of the resolution including on how transparent the Secretary-General’s report is.

Reading Between the Lines: The latest authorisation is amenable to competing interpretations, although the text denotes no clear mechanism that would allow Moscow to veto the six-month extension outright. That said, such statements from Moscow indicate that the cross-border mandate’s extension after six months is unlikely to be straightforward and will likely prompt acrimonious disagreement.