In-Depth Analysis

On 8 September, Egypt, Jordan, Syria and Lebanon agreed on a plan to supply energy-deprived Lebanon with Egyptian natural gas through the Arab Gas Pipeline, which passes through Jordan and Syria. The plan has come about following a series of high-level regional and international meetings concerning energy in Lebanon, including a four-way meeting of the involved countries’ energy ministers in Amman and a special Lebanese delegation to Syria. The plan is expected to boost Lebanon’s electricity production, generating about 450 megawatts and providing more than four hours of daily electricity to power-starved Lebanese. In addition to the much-needed power boost to Lebanon itself, transit countries involved in the deal will also benefit. While benefits to Egypt and Jordan are unremarkable, an international deal that will favour the Government of Syria is decidedly noteworthy. Critics of Damascus have interpreted the plan an end run around sanctions that will ultimately reward the regime of Bashar al-Assad, as Syria will also benefit from the transfer. This is, to some extent, true. However, regardless of potentially significant economic gains to Syria, the deal’s most important dimension may be the political implications of international engagement with the Government of Syria.

Reviving the regionally important Arab Gas Pipeline would have been legally perilous and politically impossible without a U.S. greenlight, which has raised the profile of the deal far beyond its importance to regional energy infrastructure alone. The deal came about through the waiver of specific U.S. sanctions. This has generated debate, even among uniformly anti-Assad observers. Some have argued that the U.S. is easing economic pressure on Damascus and inadvertently bolstering Syria’s dilapidated energy sector. Others suggest that the deal is part of a bid to modify Washington’s unrelenting pressure campaign against Damascus and instead use access and leverage to bring about behavioural change in the regime.

Although completed in 2003, the Arab Pipeline ceased operation during the Syria conflict due to attacks on segments in Syria and Egypt, as well as Lebanon’s inability to pay for transit. The pipeline connects four Arab states and is at the centre of energy transfer in the eastern Mediterranean. Its resuscitation bolsters the case that some Arab states are willing to bring Syria back into the Arab fold — at least in a pragmatic respect — under al-Assad’s leadership. While the Syrian Government has announced that the pipeline is operational in its territories, sabotage and interference are possible, and it is still unclear whether it will receive cash or gas in return for its transit in Syria (see below: IS Claims Deir Ali Power Plant Attack).

It is notable that the deal follows King Abdullah of Jordan’s back-to-back visits to the U.S. and Russia, during which the king advocated for a broader international recognition of Assad’s staying power as a first step toward achieving regionally beneficial outcomes, including on refugees and trade (see: Syria Update 30 August 2021). Abdullah’s statements coincided with Damascus’ hard-fought consolidation of its grip over Dar’a, in southern Syria, where Amman’s material interests in secure borders and a viable trade route to the eastern Mediterranean are on full display. Despite the energy deal, it remains to be seen if the king’s statements mark the beginning of a broader shift in regional politics vis-à-vis Damascus, although such a shift has long been discussed.

Although the deal’s most controversial dimensions concern Syria, at the heart of the matter are steps to salvage Lebanon’s paralysed economy and energy sector. Washington’s acquiescence to the deal has therefore been seen in some quarters as a means of avoiding the need to condone a difficult-to-stomach alternative to meet Lebanon’s energy needs: the arrival of Iranian tankers carrying fuel destined for Lebanon. In a twist, the tankers which have already left Iran bound for Lebanon are meant to dock in Syria with the help of Hezbollah, which will transfer the fuel overland to Lebanon. Successfully resupplying Lebanon will burnish Hezbollah’s image and cast it as indispensable to resolving Lebanon’s problems, and it will strengthen the case for reliance on Iran — not only in Lebanon, but in Syria too.

Whole of Syria Review

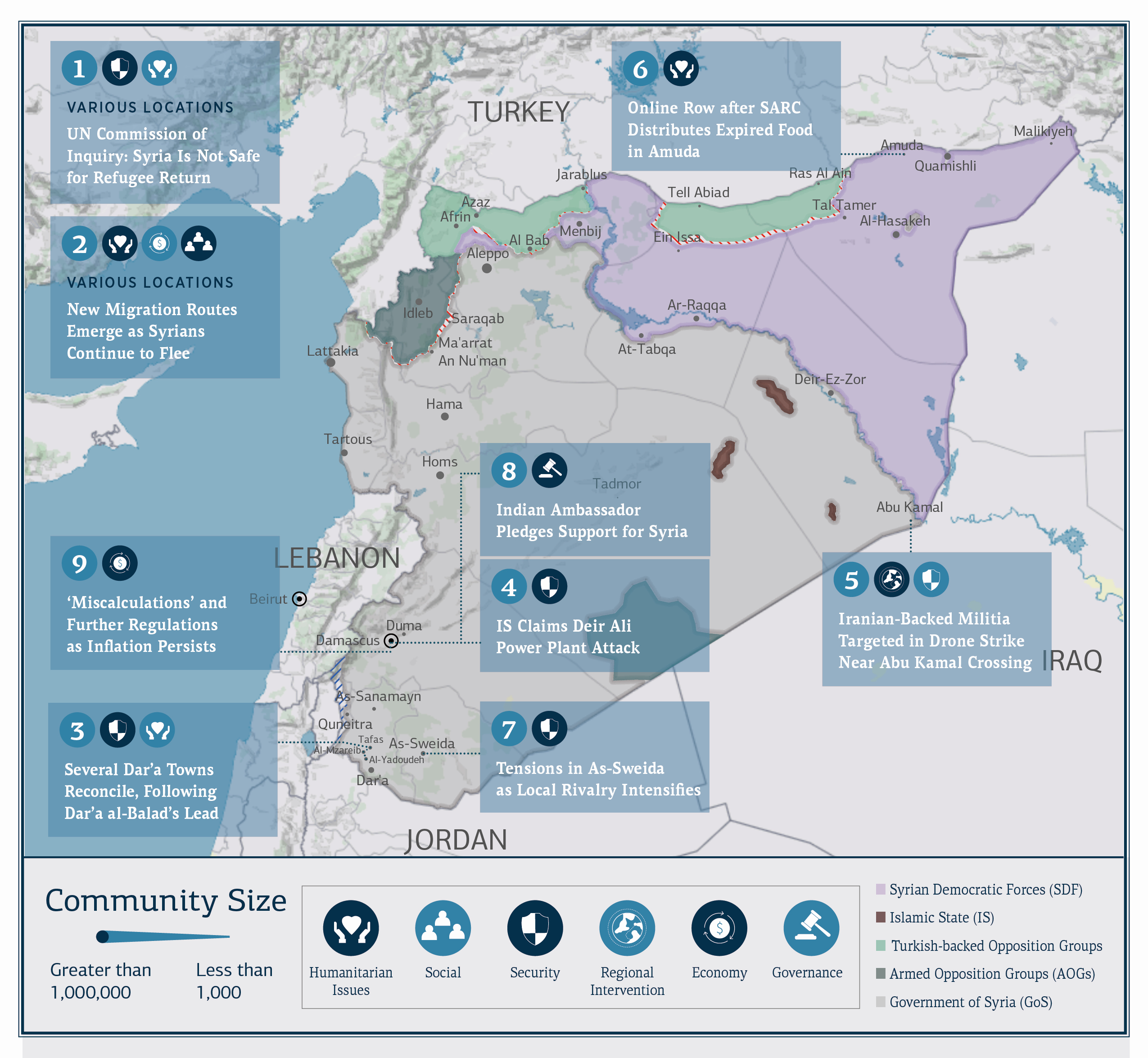

UN Commission of Inquiry: Syria Is Not Safe for Refugee Return

Various Locations: On 14 September, the United Nations Commission of Inquiry on Syria released its latest periodic report detailing rising violence in Syria, leading the specially mandated UN body to declare that Syria is not safe for the return of refugees. The report called attention to continuing violence in northwest Syria, the recent return of siege tactics, and the Government of Syria’s political rigidity, noting that “there seem to be no moves to unite the country or seek reconciliation. On the contrary, incidents of arbitrary and incommunicado detention by Government forces continue unabated.” The report noted that parties to the conflict continue to commit war crimes, crimes against humanity, and human rights violations. Relatedly, on 7 September, Amnesty International released a report documenting new cases of Syrian security forces subjecting returnees to detention, torture, and sexual violence. The organisation analysed violations perpetrated by the Syrian intelligence forces against 66 refugees, including 13 children, who have returned since 2017. Among the documented returnees, five died in detention while the fate of 17 forcibly disappeared individuals is unknown.

Meanwhile, the Lebanese authorities have announced that they will not deport six Syrian refugees who were detained after entering the country irregularly, following an outcry by human rights organisations. The six men were detained by Lebanese intelligence two weeks ago when they visited the Syrian Embassy to collect their passports (see: Syria Update 6 September 2021).

Not ready for return

The reports provide further evidence that Syria is not safe for returning refugees, despite growing pressure in host nations to accelerate return processes. These pressures have mounted as fighting in Syria has abated, with the Syrian Government consolidating control of 70 percent of the country. While the Government has publicly encouraged refugees to return, its actual practices constitute a powerful disincentive, and refugees continue to face potentially deadly risks upon return. Nonetheless, host states are reconsidering the protection they offer to Syrian refugees. Lebanon and Turkey, where many Syrian refugees face discrimination and harsh living conditions, have witnessed rising popular and political pressure on Syrians to return (see: Syria Update 2 August 2021). In parallel, Denmark and Sweden have also begun to reassess the residency permits granted to refugees from areas in Syria they consider safe, including Damascus and Rural Damascus (see: Point of No Return? Recommendations for Asylum and Refugee Issues Between Denmark and Damascus). As more states seek to normalise some or all aspects of their relationship with Damascus, the risk that Syrian refugees will be asked — or forced — to return to Syria on a basis that is unsafe, undignified, involuntary, and unsustainable will also grow.

New Migration Routes Emerge as Syrians Continue to Flee

Various locations: Since August, a new wave of migration has been taking shape as Syrians hailing from areas held by the Syrian Government are forging new pathways out of the country. Local sources have indicated that thousands of youths in various locations in Syria are under increasing pressure to flee due to difficult living conditions, highlighted by a lack of jobs, basic services, and safety. While measuring irregular outward migration is difficult, strong indicators are present. Most notably, surging demand for passports has outstripped the issuing capacity of the Department of Immigration and Passports, according to the Syrian Interior Minister. In addition, new migration routes are growing in popularity. Although there are few countries currently receiving Syrians, some have recently made arrangements to allow Syrians to legally travel at a lower cost. Egypt is reportedly the most sought-after travel destination from Syria after reducing visa fees and relaxing security approvals. Other destination countries include Iraq (Erbil), the UAE, Belarus, and Libya (see: The Syria-Libya Conflict Nexus).

Anywhere but here

While Damascus and Moscow continue to claim conditions are favourable for return, Syrians inside the country are still keen on exiting. According to local sources, thousands departed the country from Damascus, Aleppo, and Dar’a Governorates between August and September, and thousands more are waiting for the Government to issue their documents. Continuing human rights violations, arbitrary arrests, conscription, and reprisals for conflict-related events add to the complex security landscape in Syria, driving displacement abroad. Migration has been kept in check by COVID-19-related travel restrictions and limitations on Syrians’ mobility. Contrary to its rhetoric, the Syrian Government is not prepared to prevent Syrians from leaving the country. In practice, and from the perspective of Damascus, Syrians’ flight abroad reduces strain on services and infrastructure, while well-connected trafficking networks that move refugees out of the country reap financial reward. Moreover, refugees themselves continue to prop up the country with remittances, now among the pillars of the Syrian national economy.

Several Dar’a Towns Reconcile, Following Dar’a al-Balad’s Lead

Tafas, Al-Mzareib, and Al-Yadoudeh, Dar’a Governorate: On 18 September, media sources reported that the Central Committee of the Dar’a Governorate western countryside had reached an agreement with the Syrian Government’s Security Committee. The agreement includes provisions for reconciliation of wanted persons and fighters fleeing compulsory military service, local fighters’ handover of dozens of weapons, and the repositioning of Government forces at several locations inside and around Tafas. Similar agreements were reached in Al-Mzareib and Al-Yadoudeh. Recently, Government forces reached an agreement with the Central Committee in Dar’a al-Balad to end the military escalation there, relinquish hundreds of individual weapons, and establish nine military and security points in Dar’a al-Balad neighbourhoods (see: Syria Update 30 August 2021).

Kicking the can down the road?

Recent agreements in Dar’a Governorate are a sign of the success of the Government’s strategy to tighten its grip over southern Syria through additional security restrictions and a no-holds-barred approach to restive communities. The agreement allowing the stationing of Government forces inside Dar’a al-Balad has prompted other holdout communities in Dar’a to strike similar agreements to avoid further escalation. In recent weeks, Government forces have achieved remarkable progress undermining resistance in Dar’a by seizing individual weapons, carving up the Governorate through military and security chokepoints, and restricting the movement of antagonistic groups. Notwithstanding its progress in these respects, Damascus will not succeed in imposing permanent stability as long as its forces continue to carry out human rights violations, refuse to release detainees, and fail to provide basic services. Over time, Damascus can be expected to soften its tactics in Dar’a, while methodically pursuing absolute control. Access conditions, mobility, and security are likely to improve in the medium term, though assassinations and other acts of violent resistance are unlikely to be a thing of the past.

IS Claims Deir Ali Power Plant Attack

Damascus Governorate: On 17 September, media sources reported a power outage in Damascus and its countryside. According to Minister of Electricity Khaled al-Zamil, the outage was due to an attack on a feeder line to the Deir Ali power plant. The Islamic State (IS) has claimed responsibility for the attack as part of a plan for “economic war.” The incident coincided with another attack on power lines in Harran al-Awamid, located between Deir Ali and Damascus International Airport. The attacks come on the heels of an agreement between the governments of Syria, Jordan, Egypt and Lebanon to revive the Arab Gas Pipeline to supply Lebanon with Egyptian gas via Jordan and Syria.

Regional deal, localised risks

This is not the first time the feeder gas lines to Deir Ali station, which is responsible for generating electricity in southern Syria, have been targeted. However, the timing of the attack is significant, and it can be seen as a response to the Arab Gas Pipeline agreement to supply Lebanon with Egyptian gas through Jordan and Syria. The Deir Ali station is fed by the Arab Gas Pipeline, which runs through the Syrian desert some 30 km south of Damascus International Airport. At least in theory, the affected section of pipeline is insulated from attack by the control of Government forces and Iranian militias around the capital. However, IS cells have spread beyond northeast Syria since the group was routed in spring 2019. With high mobility in the Badia, IS cells will be able to launch attacks on the pipeline or other related energy infrastructure, thus giving the group the capacity to sabotage the Arab Gas Pipeline deal.

The Syrian Government announced that the pipeline would be repaired in short order; however, the incident is unlikely to be the last of its kind. Speculation has been rife concerning the political dimensions of the attack, and many observers have noted that Iranian forces have ample incentive to challenge the new Arab Gas Pipeline deal, which is itself an affront to Iran’s own strategy to supply Lebanon with energy. Though speculative, an attack by forces loyal to Iran would hint at fear in Tehran that Damascus views rapprochement with Arab countries — and the West — as a more attractive long-term proposition than bilateral ties with Iran.

Iranian-Backed Militia Targeted in Drone Strike Near Abu Kamal Crossing

Abu Kamal, Deir-ez-Zor Governorate: On 15 September, various media sources reported that Iranian-backed militia vehicles were targeted by drone strikes as they crossed from Iraq into Syria through the Abu Kamal crossing. The number of casualties is not yet confirmed. There is no clear indication of who conducted the strike, but it is widely believed that either the U.S. or Israel is responsible.

Drone denial

Iran will be watchful over the potential for future attacks in the strategic crossing point. The Abu Kamal crossing lies along the main land route that links Iranian proxies in Iraq to their confederates in Syria and Lebanon. Destabilising this route would compromise Iran’s supply lines to both countries. While the route’s utility to Iran is obvious, the identity of the attacking force is less clear. Between the two major powers most openly opposed to Iran’s presence in the region, the U.S. is more likely to be responsible for the incident, although Washington has denied involvement. Israel, which has remained silent on the matter, does not typically conduct strikes on Syrian territory. Both parties have previously launched attacks on Iran-linked sites in Iraq-Syria border areas, and such attacks are likely to be repeated in the future.

Online Row after SARC Distributes Expired Food in Amuda

Amuda, Al-Hasakeh: On 14 September, media sources reported that food aid (including lentils, chickpeas, and salt) delivered to Amuda in northern Al-Hasakeh was expired at the time of distribution. The packaging bore a September 2020 expiry date, according to images circulating online. Local sources confirmed these reports, stating that the Syrian Arab Red Crescent (SARC) delivered the food baskets. The food was distributed to displaced people from Ras Al Ain who are now sheltering in Amuda. Local sources stated that the food was procured locally.

Food fight

It is not uncommon for aid organisations to deliver food that is approaching expiry, yet the distribution of expired food has — like improper storage and transit — been linked to mass food poisoning in Syria. While it is important for implementers and donors to be aware of such risks, quality assurance problems often arise in upstream portions of the value chain. Vendors have been known to repackage expired food to avoid detection or liquidate aging stock, particularly if logistical issues, permitting, or security issues have complicated inventory procedures. Donor agencies should be mindful of the continued risk posed by expired or adulterated food, particularly as conditions in Syria grow more precarious and vendors and producers alike seek to maximise their returns.

Tensions in As-Sweida as Local Rivalry Intensifies

As-Sweida city, As-Sweida Governorate: On 15 September, tensions arose in As-Sweida city between the Rijal al-Karama Movement and local militia groups sponsored by Syrian Military Intelligence and led by Raji Falhout, a gang leader backed by Military Intelligence. Falhout’s militias blocked several roads in As-Sweida city and surrounding towns, and kidnapped a number of civilians in addition to two members of the Rijal al-Karama Movement. In response, the latter deployed dozens of its members to encircle the Military Intelligence and Security branches, while blocking all roads leading to Atil, Falhout’s hometown. Following mediation led by religious and civic figures, Rijal al-Karama demanded the suspension of the blockades, holding Falhout accountable for recent crimes against civilians, and the expulsion of militia group leaders from As-Sweida. The local Druze religious leadership accused “external actors” (widely interpreted as a reference to the Liwa Party) of fuelling the strife in the governorate, and called for both sides to de-escalate and preserve the “blood of As-Sweida’s sons.”

These incidents followed skirmishes that took place in August and September between the As-Sweida National Defence Forces and local militia groups such as the Falhout Group and the ‘Counter-Terrorism Force’ — the armed wing of the newly established Liwa Party (see: Syria Update 26 July 2021).

Sowing instability

The clashes have caught some observers flat-footed, as As-Sweida is generally seen as the stable, semi-autonomous neighbour of restive Dar’a Governorate. While de-escalation has contained the situation for the time being, undercurrents of dissatisfaction run deep throughout the governorate, and the formation of new armed entities points to mounting social tensions stoked by Damascus. Despite not witnessing any major military operations, As-Sweida has undergone severe security deterioration in recent years, due partly to tenuous conditions that prevail nationwide, but also because of efforts by Damascus to instrumentalise local militias and criminal groups, such as the National Defence Forces and Nusur al-Zawba’a, to counter the influence of emerging breakaway factions. Members of these groups are sponsored by security branches that provide them with security cards to facilitate their passage at checkpoints and protect them from other groups. In the long run, the Government’s strategy to weaponise these groups may weaken rivals and force the population of As-Sweida to accept a larger role for central authorities. In the near term, this will jeopardise stability and pose risks to humanitarian operations in a region that hosts a large number of IDPs from other governorates. Aid actors considering implementation in As-Sweida must beware that although the region has a less overt Syrian Government presence, other risks remain.

Indian Ambassador Pledges Support for Syria

Damascus: On 8 September, Indian ambassador to Syria Mahinder Singh Kanyal met with Syrian Prime Minister Hussein Arnous to discuss relations between the countries. Without saddling New Delhi with pledges of specific forms of support, Kanyal stated that India “is committed to continuing to provide technical and humanitarian support, and to contribute to capacity building and human resource development according to the requirements and needs of Syria.” The Indian Foreign Ministry has in recent years described its relationship with Syria as one of “friendly political relations based on historic and civilizational ties, experience of imperialism and of being colonised, [and] a secular, nationalist and developmental orientation.”

International rapprochement? Not so fast

Syria continues to seek stronger ties with Asian states with soft — if any — commitments to a liberal, rights-based agenda. Although Western powers may find India’s pledge troubling, it is yet to be seen how this support will materialise. For now, India’s vague assurances are important for Damascus politically, but do little for its bottom line. The commitment calls to mind images of scant supplies of waterlogged personal protective equipment dispatched to Syria by a notionally sympathetic Chinese government at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Although Damascus has cast about for new sources of support as the West remains on the sidelines, governments elsewhere have been slow to deliver on hard forms of support — and they will likely struggle to provide such support at all.

‘Miscalculations’ and Further Regulations as Inflation Persists

Miscalculations in reported exports:

Damascus: On 12 September, Deputy Economy Minister for Trade Affairs Bassam Haidar stated that as of July 2021, Syrian exports for 2021 amounted to approximately 400 million EUR (approx. 471 million USD), for a monthly average of 57 million EUR. Haidar stated that during the first seven months of 2019 and 2020, exports were valued at 523 million EUR and 618 million EUR, respectively. As such, Syria’s exports are down 35 percent in 2021. Without referencing Haidar’s statements, media sympathetic to Damascus have clapped back at the figures, with the Syrian Arab News Agency (SANA) and Russia Today recasting them to show an increase in exports year over year. On 16 September, SANA quoted an undisclosed report by the Ministry of Economy and Trade stating that Syria’s monthly exports as of July averaged 57 million EUR euros in 2021 and 52 million EUR in 2020.

Increased regulations to bridge the deficit gap

Syria has struggled to achieve a sustainable balance of trade. Unable to bridge the gap by increasing its exports, the Government has been attempting to curtail imports. To this end, it created an ‘import substitution’ programme in February 2019, aiming to reduce foreign reserve expenditures, protect domestic industries, improve self-sufficiency, and attract investments. The plan reportedly ended support for the importation of almost one thousand products (about one quarter of the total), and it outlined state support for domestic industries to replace 67 of them, including medical products, milk powder, and crop agricultural seeds. More recently, on 1 September, the Central Bank of Syria issued decrees 1070 and 1071 concerning the financing of basic good imports (sugar, rice, cooking oil, medicine, etc.) at the official exchange rate through banks and licensed hawala agencies. This essentially allows importers to buy dollars at much-reduced official rates, provided they guarantee the imported goods will be sold at prices determined by the Ministry of Domestic Trade and Consumer Protection. Meanwhile, decree 1071 attempts to increase control over foreign currency exchanged on the market by mandating that exporters exchange 50 percent of the value of exported goods in foreign currency at the official exchange rate — an apparent attempt to increase control over foreign currency exchanged in the market.

The plans are unlikely to have the broad, positive impact that is needed. The head of the Exports Committee at the Chambers of Commerce Syndicate, Abdelrazzak Sebahi, told a Syrian newspaper that the decrees will systematise the export process. His deputy, however, stated that many exporters will be driven from the market due to increased red tape and banking complications. Already, reports by local news outlets indicate that exporters of fruits and vegetables in Damascus have stopped working two days after the decrees were issued.

Open-Source Annex

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below..

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

Syria cement plant at centre of terror finance investigation ‘used by western spies’

What Does It Say? The Lafarge Cement factory near Ar-Raqqa is under investigation for financing terrorism through taxes it paid while IS was in power. The factory was reportedly used as an international hub to attempt to rescue hostages held by IS.

Reading Between The Lines: The rescue attempts failed, and the company inadvertently helped fund IS.

Autonomous Administration warns of a “disaster” due to drought in northeastern Syria

What Does It Say? The Autonomous Administration has sounded the alarm bells that the ongoing drought will likely affect the agricultural sector of the areas under its control.

Reading Between The Lines: A poor harvest will affect livelihoods and the area’s food security.

How Syria Changed Turkey’s Foreign Policy

What Does It Say? The article lays out how Turkey’s actions in Syria have shaped its overall foreign and domestic policies, including by using its actions against Syrian Kurds to drum up support during elections.

Reading Between The Lines: Turkey has used the Syrian refugee situation as leverage with the EU on a number of occasions. In addition, their hostilities towards the SDF have strained its relationship with the U.S.

Turkey’s blind eye to jihadis worsens its predicaments in Syria

What Does It Say? Turkey has attempted to fuse smaller factions in northern Syria into a regular army in order to prevent another Syrian Government and Russian offensive in Idleb.

Reading Between The Lines: The smaller groups frequently clash and commit crimes against the civilian population. In reality, these groups are effective war economy profiteers, and their capacity to create a unified front is dubious.

What the Global War on Terror Really Accomplished

What Does It Say? The U.S. has changed the way extremist groups think and act.

Reading Between The Lines: Rather than focusing on one-off attacks, jihadist groups are engaging in long-term planning within the boundaries of their own countries.