On 14 September, Presidential Decree No. 237 officially created the Northern Gate of Damascus Regulatory Area, a new development district in Qaboun and Harasta, on the outskirts of Damascus. Faisal Srour, a member of the Damascus Executive Council, stated that the regulated area measures 2,000 donum, extending from Harasta to the Panorama Circle in Qaboun. The plan is based on the controversial Law No. 10 (2018), which permits the state to confiscate lands whose owners fail to prove their ownership within a specified period, allowing the state to seize up to 20 percent of lands within the regulated areas for service investments it favours. According to Srour, landowners will soon be invited to submit objections to be settled by a special committee. The decree builds on previous urban plans for the area, which encompasses heavily damaged former opposition enclaves in what was once among the foremost industrial centres of Damascus (see: Syria Update 20-29 June 2019 and Syria Update 29 August-4 September 2019). The plan may ultimately displace thousands of residents by reconfiguring a transient, informal neighbourhood spattered with light industry into a leafy suburban enclave for Syria’s wartime rich.

According to the Damascus Council, the industrial area of Qaboun will be transformed into a financial and services district, and factories will be relocated to the Adra industrial area. All lands with industrial and agricultural utility will be rezoned; according to Srour, “Damascus has never been and will never be an industrial city.” He added that the Qaboun-Harasta regulatory plan overcomes the pitfalls of the much-maligned — but stalled — Marota and Basilia city master plans, issued in 2012 via Legislative Decree No. 66.

Property owners will be compensated with shares in residential units once the area has been developed. In the meantime, they will receive 5 percent of the value of their properties as housing remuneration for up to two years, or until the Government provides them with interim housing. Former renters in the area will also receive interim housing, but will not be granted shares in the new developments. To qualify for these benefits, renters and owners will be required to submit proof of residence or ownership. Those holding official ownership certificates will be exempted from applying for special proof of ownership, but these are in a minority, as the area was inhabited on a largely informal basis, and many residency agreements there have historically been negotiated verbally.

Outcast Damascenes

The physical destruction of Syrian communities and the displacement of millions of residents have been among the most consequential aspects of the conflict. In many cases, the worst damages were inflicted by forces loyal to the regime of Bashar al-Assad, and in many cases, the Government of Syria’s plans to resolve the resulting crises threaten further harm to vulnerable populations. As such, land and property management and selective reconstruction have become a tool for self-enrichment and political control (see: Political Demographics: The Markings of the Government of Syria Reconciliation Measures in Eastern Ghouta). The return of refugees to their former homes is threatened by low rates of official land registration (especially in rural and poor communities where destruction has been concentrated) and expropriation laws. High-end development projects like the Northern Gate project overtly promise to wrest control of these areas from the urban poor, IDPs, and Palestinian refugees, and deliver them into the hands of the elite.

Such impacts are taking shape across Syria. For instance, on 10 September, Talal Naji, the new head of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General Command, stated that “Bashar al-Assad has ordered that displaced residents of the Yarmouk Camp be permitted to return without any restrictions or barriers.” According to Naji, Damascus City Council will begin removing debris from primary and secondary roads and rehabilitating basic infrastructure including sewage, water, and electricity systems, in order to provide a suitable environment for residents’ return. Moreover, according to media sources, the Syria Trust for Development will implement a number of early recovery projects, including by providing financial support for the opening of small groceries and supermarkets in the neighbourhood. On 22 September, the Action Group for Palestinians of Syria reported that debris removal from residential neighbourhoods in the largely Palestinian enclave was carried out by private companies at the expense of residents, who were asked to pay out of pocket. The cost of removing debris from dilapidated houses thus increased significantly, reaching up to 10 million SYP (2,900 USD) per unit.

A troubling blueprint

Special attention must be given to policies that alter Syrian communities’ socio-economic and cultural identity, and uproot ‘unwanted’ social, economic, and political groups (the working class, refugees, and dissident communities). No doubt, urban development projects and zoning regulations were weaponised to alter the socio-economic status of Syrian urban centres prior to the current conflict. Policies such as these were adopted in the beginning of the millennium with the Syrian Government’s gradual shift toward a neoliberal orientation. Yet, the conflict has turbocharged these dynamics by offering up many maligned areas as a tabula rasa where disfavoured population groups have been displaced or can be silenced through the appearance of due process.

Decree No. 237 showcases Syria’s blueprint for reconstruction and urban development, which will deliberately prevent thousands of displaced Damascenes from returning. Those who fail to prove ownership will lose not only properties, but also their historical foothold in the city. Reconfiguring high-density neighbourhoods as medium- or low-density enclaves will drive prices up, drive out former inhabitants, and usher in a post-war elite. Rezoning industrial and agricultural areas is a necessary first step in this transformation, and in areas like Qaboun, it will batter once-flourishing local industry.

Relocating industrial areas that have historically existed on the periphery of the city will have wide reach by curtailing livelihood opportunities for those who lived nearby, thus pushing them toward unemployment, relocation, or migration. In addition, changing the social profile of neighbourhoods such as Yarmouk and Tadamon — which have hosted maligned social groups such as Palestinians and IDP Syrians from the occupied Golan — will weaken and fragment these groups and hamper their ability to defend their collective interests and civil and political rights. Ultimately, the biggest losers of the Government’s selective reconstruction plans and exclusive urban development blueprint are the very social groups most impacted by the conflict. Unsurprisingly, the biggest winners are the Assad regime’s cronies and urban developers.

Whole of Syria Review

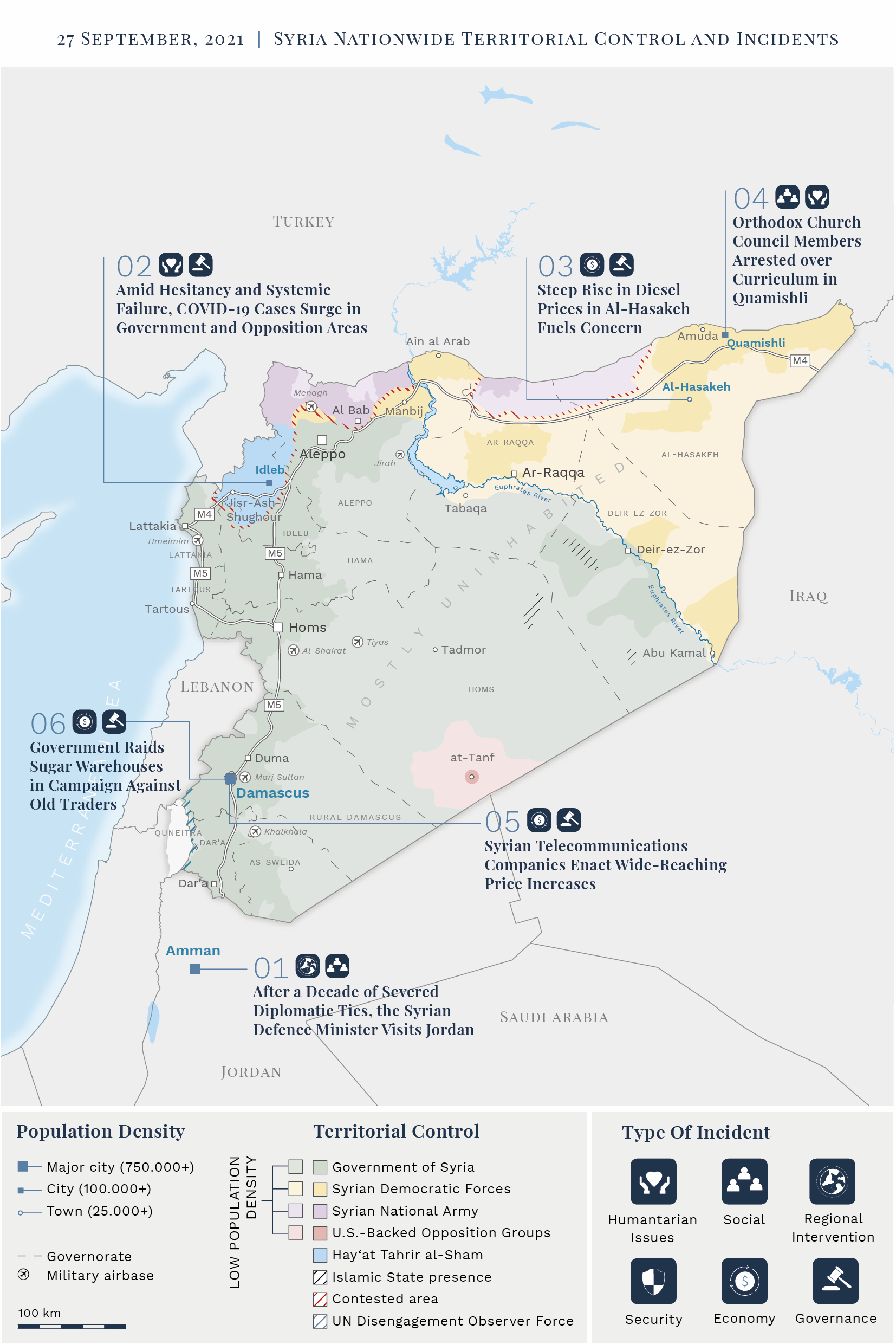

After a Decade of Severed Diplomatic Ties, the Syrian Defence Minister Visits Jordan

Amman: On 19 September, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff of the Jordanian Army, Major General Yousef al-Huniti met the Syrian Government’s Minister of Defence, Major General Ali Ayoub, in Jordan. The visit by the Syrian Defence Minister is the highest-level meeting between the two sides since the start of the conflict in Syria in 2011. According to the Jordan News Agency, the meeting served as a venue to discuss common issues including border security, trade, cross-border drug smuggling, and the situation in southern Syria.

Economic benefits amid security challenges

The Syrian Defence Minister’s visit to Jordan comes as Russia attempts to end Damascus’s regional isolation and open it up to Arab countries, a general ambition which Jordan itself now shares. For its part, Jordan is seeking material benefit, including the economic boon of restoring cross-border trade, expanding the agreement to transport gas to Lebanon through Jordan and Syria, and a greater role as a Western-friendly regional interlocutor with Damascus (see: Syria Update 20 September 2021 and Syria Update 30 August 2021). Security is also a vital aspect of the two countries’ evolving relationship. The latest meeting focused on common security issues, particularly the continued flow of drug shipments through southern Syria and the fight against terrorism.

All told, Jordan’s flip-flop on Syria has been staggering. It has transformed from a host to Western-backed armed opposition platforms overtly seeking to overthrow the Assad regime into a leader in what it views as pragmatic regional rapprochement. While Amman’s vision has shifted according to economic interests, security issues are also of foremost importance. These include Iran’s growing influence in southern Syria and the drug trade across the Syrian-Jordanian border. Collectively, security concerns will be an obstacle to full normalisation with Syria, as will Russia’s failure to guarantee stability in southern Syria (see: Syria Update 2 August 2021). Neither the Syrian Government nor Moscow has the capacity to curtail Iranian influence in southern Syria, nor can they realistically limit the drug trade and smuggling, which have become backbones of Assad regime figures (see: The Syrian Economy at war: Captagon, Hashish, and the Syrian Narco-State). Fluid security conditions in southern Syria will place a limit on Jordan’s willingness to work with Damascus, yet Amman’s appetite for engagement likely ranges far beyond mere economic recovery.

Amid Hesitancy and Systemic Failure, COVID-19 Cases Surge in Government and Opposition Areas

Damascus, Idleb: On 22 September, media sources reported that all hospital beds in Damascus designated for COVID-19 patients are full. Dr. Tawfiq Hassaba, the Ministry of Health’s director of readiness and emergency, stated that over 2,000 patients are being treated for COVID-19 in Lattakia, Aleppo, Damascus, Rural Damascus, and Hama governorates. Despite high infection rates, Hassaba stated that the death toll has dropped in comparison with previous waves, and patients are responding better to treatment. Schools have recorded 150 cases of COVID-19 since the start of the scholastic year. As elsewhere, adolescent cases are reportedly less severe, and the infected are being directed to isolate at home for 14 days.

Relatedly, cases in Idleb and northern Aleppo are surging as the health system in that part of the country also reaches full capacity. Daily COVID-19 cases in Idleb reportedly reached more than 1,500 in September. Furthermore, the Idleb Health Directorate has warned that the region’s health system is at full capacity, and it is on the verge of collapse. Dr. Rifaat Farhat, a senior health official at the Idleb Health Directorate, stated, “If the situation continues, the health system will become paralysed.” NGOs working in the health sector in Idleb have stated that restrictive and preventative measures must be put in place to slow the spread of the virus. These measures include making masks mandatory in public places, suspending in-person working and school hours, mandatory testing for those arriving from other regions, limiting public gatherings, and disseminating reliable information.

Vaccine mistrust

Underlying inequalities across Syrian regions continue to pose different challenges in each area of the country (see: Syrian Public Health after COVID-19: Entry Points and Lessons Learned from the Pandemic Response). One constant across regions is the fact that Syria’s COVID-19 response has been slow, yet the conflict alone is not to blame for now-surging case numbers. In Government areas, local sources estimate that vaccinated people make up 3-4 percent of the population. According to these sources, the reason for the low number is not merely limited access, which was the principal concern earlier this year, but also vaccine hesitancy borne of popular unwillingness to place faith in the Government of Syria (see: Syria Update 6 April 2021). Patients remain hesitant to seek out medical care for fear of inadequate treatment or abuse in Government institutions.

Idleb is facing its own challenges regarding COVID-19. In August, China sent 300,000 doses of the Sinovac vaccine to the region, and while vaccination rates in Idleb are believed to be higher than in Government areas, the region’s infrastructure is still inadequate for needed efforts to combat the spread of infection. Years of conflict — including deliberate targeting of health infrastructure by Government forces — has left the health system in Idleb in dire condition and ill-suited to combatting the pandemic. Aid sector approaches to COVID-19 in Syria have been significant and widespread, but they will have to be sustained and more expansive to counteract other factors, including the reality of Syria’s damaged health sector and widespread vaccine hesitancy.

Steep Rise in Diesel Prices in Al-Hasakeh Fuels Concern

Al-Hasakeh: On 20 September, media sources reported that fuel prices in the Autonomous Administration had increased by as much as 400 percent, with authorities offering no official comment on the staggering increase at the time of writing. The litre price of diesel in the so-called Jazira administrative region, reached roughly 410 SYP (0.12 USD), up from 100-150 SYP (0.03-0.04 USD). Sources report conflicting statements by fuel station owners and Autonomous Administration officials. According to an official from the Autonomous Administration, gas stations are free to set their own prices, while fuel station owners contend that prices are effectively dictated by the Autonomous Administration, which has a hand in shaping procurement and region-wide fuel marketing. The Kurdish National Council, a minority opposition party, has stated that it plans to conduct protests against the price hike.

Fueling local unrest

Absent an official statement concerning the rise in diesel prices, it is difficult to discern what prompted such a major increase in fuel prices. The cost of fuel is a particularly sensitive issue within the Autonomous Administration, given its status as Syria’s primary oil-producing region. A price hike in May sparked region-wide protests (see: Syria Update 24 May 2021), which were met with a deadly crackdown. At that time, the increase was quietly dropped. However, the protests primed the pump for further deadly demonstrations against conscription. Aid actors must now be aware that a massive price hike may prompt public outrage and a harsh clampdown (see: Syria Update 7 June 2021).

It has been suggested that the fuel price increase constitutes an attempt to stem cross-line and cross-border smuggling. In that respect, it is notable that the price hike comes a week after the Qaterji company resumed the periodically halted cross-line oil trade. If the Autonomous Administration succeeds in reducing smuggling by raising costs, it will be a pyrrhic victory of questionable wisdom. Left unaddressed, there will be economic consequences on fuel-dependent services and sectors, including agriculture, transport, aid work, and market prices. Diesel is also used in all-important electricity generation. Finally, it may prompt violent local protests, destabilising the region and undermining local authorities who have shown a willingness to halt local unrest through violent means. Interestingly, a full lockdown has been announced in the Jazira region, ostensibly to stop the spread of COVID-19. While the restrictions may have public health benefits, it is also likely that the Autonomous Administration is hoping that keeping local populations at home will allow it to kill two birds with one stone.

Orthodox Church Council Members Arrested over Curriculum in Quamishli

Quamishli, Al-Hasakah Governorate: On 21 September, media sources reported that the Internal Security Forces (ISF), commonly known as the Asayish, arrested two members of the Syriac Orthodox Church Council in Quamishli. Both men were later released due to public pressure. The arrest was triggered by the Church’s refusal to adopt the Autonomous Administration’s educational curriculum, in use in schools across Al-Hasakeh. Despite the Autonomous Administration’s efforts to impose a Syriac-language version of its own curriculum for students affiliated with the Syriac Orthodox Church Council, the latter continues to use the Syrian Government Ministry of Education curriculum. The Church’s refusal is motivated by apprehension of the consequences of adopting a curriculum different than that of the Syrian Government, including license revocation and non-accreditation.

The curriculum has been a point of contention in northeast Syria since it was implemented by the newly established Education Authority in 2014. Critics opposed the curriculum based on linguistic and ideological grounds as well as the fact that it is not recognised outside northeast Syria. The ISF has previously resorted to force to ensure its monopoly over education is not challenged. In January 2021, the ISF arrested at least 61 teachers for teaching the Syrian Government’s curriculum and conscripted 34 of them into the SDF’s ranks. In 2018, Kurdish authorities also shut down several schools run by the Syriac Christian minority.

Education migration

Despite detentions and other forms of suppression by the ISF, resistance toward the curriculum continues, and it is among the flashpoint social and service-related issues driving ‘vertical’ tensions and ethnic frictions in northeast Syria (see: Northeast Syria Social Tensions and Stability Monitoring Pilot Project). There is a pervasive belief that the Autonomous Administration curriculum favours the Kurdish language and the political and historical perspectives of the dominant Kurdish authorities in the region. In practical terms, these issues also run up against the demands of popular acceptance and official accreditation, and many object to the curriculum out of fear that their children will not be able to continue their education or find work in other regions. This has pushed many parents from minority ethnic and religious backgrounds to register their children in schools that continue to use the Syrian Government’s curriculum, even if those schools are overcrowded and underserviced. If the ISF and the Syriac Orthodox Church do not reach a sustainable agreement pressure will increase for such families to migrate or continue enrolling their children in Government schools, lest they be forced to continue in defiance of local authorities. In the long term, such grievances may pose a reputational risk to donor-funded education work. They will also reinforce historical patronage schemes by which the Assad regime has established itself as the protector of minority communities. In doing so, they will further undermine stability in northeast Syria.

Syrian Telecommunications Companies Enact Wide-Reaching Price Increases

Damascus: Syriatel, Syria’s main telecommunications provider, will raise prices for internet, television, and phone bundles — more than doubling the cost of some services — starting in early October. While the increases vary across services, virtually all aspects of Syria’s IT sector will become more costly. For example, landline phone subscriptions will more than double in price, with monthly subscriptions increasing from 200 to 500 SYP (0.14 USD) and fixed costs rising from the 4,500 SYP to 10,000 SYP (roughly 3 USD). The price of internet packages will increase by around 40 percent. The new prices are meant to reflect increasing costs to local internet and telephone providers, who are responsible for fuelling diesel-run power generators and paying internet providers abroad in foreign currency.

Taxing the poor

The news comes on the heels of reduced internet and phone connectivity in recent months due to increasingly common power cuts and fuel shortages in Government of Syria-controlled areas. In essence, Syrians are being pushed to pay more for less, and reduced connectivity will disproportionately impact the most economically marginalised. The development likewise presents challenges for aid practitioners reliant on digital communications and marketing for their own outreach and beneficiary engagement. Though COVID-induced, a shift toward digital programming is now a mainstay of many relief activities in Syria and elsewhere. Implementers have noted greater beneficiary reporting in sensitive sectors such as gender-focused programming and mental health and psycho-social support via digital implementation (see: LGBTQ+ Syria: Experiences, Challenges, and Priorities for the Aid Sector – COAR). Activities such as these are at risk from connectivity issues and if increased service fees force Syrians to eschew internet bundles, thus leaving some would-be beneficiaries on the wrong side of the digital divide. Absent innovation in the telecoms sector, few mitigations are readily available in Government-held areas of Syria. NGOs themselves may deem fit to provide internet and phone bundles to beneficiaries, yet doing so would present risks of its own. Major telecommunications providers including Syriatel are broadly sanctioned, making engagement with the sector problematic, even for long-standing partners. Instead, the sector on the whole has been deeply ingrained into networks and dynamics surrounding the al-Assad family and its business and humanitarian ventures in recent years amidst further isolation from the international market.

Government Raids Sugar Warehouses in Campaign Against Old Traders

Damascus: The Government’s Ministry of Internal Trade and Consumer Protection has carried out a campaign against businesses owned by Tarif al-Akhras, the uncle of Asma al-Assad, as well as other traders in Homs Governorate. Reportedly, close to 2,000 tonnes of sugar was seized in mid-September at the warehouses that belong to Trans Orient, a company owned by al-Akhras. In parallel, the Ministry of Finance reportedly raided several trading, money transfer, and food processing companies in Homs Governorate. The declared intentions of the Internal Trade Ministry’s campaign were to reduce sugar prices and increase availability by breaking up the traders’ monopoly. This came after interruptions to Syria’s sugar supply, reportedly triggered by a pricing dispute that erupted between traders and the Ministry. On 17 September, Amr Salem, the newly appointed Minister of Internal Trade and Consumer Protection (see: Syria Update 16 August 2021), stated that traders supplied only a small fraction of actual imports, delaying fulfillment as they sought higher prices in recognition of a global rise in sugar prices. According to Salem, the stockpiled sugar was bought and imported prior to the surge, and should be compensated in accordance with the price ceilings set by the Central Bank. Following the raids, both subsidised and unsubsidised sugar will be marketed through the ration card in order to monitor distribution.

Hitting the sweet spot: Syria’s old oligopoly

Beyond the local market dynamics and the Government’s efforts to curb basic commodity shortages, the campaign on sugar, and food processing businesses generally is primarily motivated by competing interests among Assad regime cronies and Government contractors. It should be noted that around the same time the raids were conducted, the Syrian Trading Establishment contracted businessperson Samer Foz, who rose from obscurity during the conflict, to be the country’s main supplier of sugar.

The raids send a clear message: only businesses closely connected to the Assad regime’s inner circles are welcome to operate at the highest levels in Syria. Al-Akhras, who is one of Syria’s most influential food products traders, was recently removed from the UK’s sanctions list. While the reason for his delisting remains unclear, it follows a falling-out between al-Akhras and the Assad regime (see: Syria Update 23 August 2021). It is likely that the Government’s behaviour signals its growing lack of trust in the pre-war business oligarchy, which could be liable to prioritise its own interests over the regime’s. Relatedly, during the week of 13 September, the Ministry of Finance ordered a precautionary seizure of assets of over 650 traders in Aleppo Governorate for what it described as tax evasion practices. This is part of a pattern of behaviour which famously began in 2019 with the prosecution of Rami Makhluof, the President’s first cousin, and the seizure of his assets in Syria. Makhlouf was Syria’s most influential business person before the war (see: Syria Update 29 August 2019).

Guaranteeing a more submissive business class might be imperative if the Government continues its restrictive measures. Continued campaigns against the pre-war business class indicate that more unpopular economic policies are on the way. By only supporting business elites that emerged during the war, the Government guarantees that its future policies are met with less criticism from within.

Open-Source Annex

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below..

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

US Strike Targets al-Qaeda in Syria.

What does it say? After conflicting communications over American responsibility for a drone strike in Idleb, the U.S. Central Command confirmed that it had carried out a strike against two al-Qaeda targets.

Reading between the lines: The first strike of its kind in Idleb in 2021 and amidst mounting criticisms about the haphazard use of drone warfare by the U.S., the event indicates that U.S. President Joe Biden’s counterterrorism policy in Syria will, in many ways, resemble that of past administrations.

Government Pressures Aleppo’s Business Community as Rare Tensions Trigger Strikes, Media Reports

What does it say? A coordinated, multi-levelled effort was carried out by the regime to crack down, once again, on Aleppo’s business community through imposing new customs and taxes, and even raiding some businesses.

Reading between the lines: The move perpetuates a pattern of crackdowns on business operations in Aleppo, which have escalated tensions between Aleppan business owners and the state throughout the year. The policies present opportunities for a cash-strapped government to hoover up remaining capital in Syria, while severely limiting prospects for small and midsize businesses in Aleppo. (For more, see: COAR weekly update, September 6, 2021.)

Returnees to Syria: What are the reasons for reverse migration from Germany?

What does it say? The article presents accounts from Syrians who migrated to Germany over the course of the war and recently returned to different areas of Government-controlled Syria.

Reading between the lines: The report highlights several factors that fly in the face of safe, dignified return: migrants are pushed out of Europe due to financial challenges, a lack of psychosocial support, and difficulties with social integration.

Syria after the fall of Kabul: A European perspective

What does it say? The piece argues that European policymakers focused on Syria should address the possibility of haphazard policy by the Biden administration in light of the American withdrawal from Afghanistan, which would necessitate a burden-sharing agreement between American and European actors and heightened diplomacy.

Reading between the lines: Recent actions by the Biden administration in Syria do more to foreshadow the administration’s Syria policy than the Afghanistan withdrawal. Having said that, Washington lacks a clear Syria policy.

“Death Boys” in Syria: Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps and What Fuels Its Dream

What does it say? The article sheds light on the conscription of Syrian children into Iranian militias in Syria.

Reading between the lines: The article outlines the reasons Syrian children are conscripted into Iranian militias, shedding light on recruitment campaigns carried out by Iranian militias in Deir-ez-Zor and the financial conditions that force many to join.