In-Depth Analysis

On 1 October, Syria was reportedly readmitted to the communication network of Interpol, the international police organisation, after applying “corrective measures” to Syria in 2012. The readmission will reportedly allow Damascus to access data hosted by the agency and communicate with other member states. Critics have described the decision as “a dangerous development” that will provide the Government of Syria a legal tool to pursue political dissidents abroad. Some fear it will have a chilling effect on Syrians abroad, by complicating asylum procedures and impeding their movement, even in places where the Syrian Government itself has no direct reach. While critics have warned that the Government will now be able to issue international warrants known as “red notices,” Interpol’s secretariat has reportedly clarified that it can withhold publishing such requests, which prompt member states to locate, arrest, and potentially extradite wanted individuals.

In addition to possible abuses by the Government, the optics of Syria’s readmittance to an international law enforcement consortium with a strong European identity and a mandate to investigate war crimes have prompted deep introspection. The most notable cause for concern is the Syrian Government’s record of abuses. To make matters worse, it has made repeated maneuvers to dodge legal accountability for crimes committed during the conflict. As if to emphasise this impunity, only days after Syria’s return to Interpol was announced, Rifaat al-Assad, uncle of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, was welcomed to Syria after three decades in exile in Europe. He was allowed to return despite his banishment by Hafez al-Assad specifically to “prevent his imprisonment” in France over embezzlement.

Although the internal processes that have apparently brought Syria back into Interpol remain unclear, it is notable that two Arab states, Jordan and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), that are eager to restore deeper ties with Damascus currently occupy seats on Interpol’s executive board. All told, Syria’s return to interpol is the most concrete example to date of the momentum building behind regional actors seeking piecemeal normalisation with Damascus. The return is likewise undergirded by either the endorsement or indifference of Western powers that have for a decade sought — and seemingly failed — to isolate and hold the Assad regime to account.

The road to Damascus

Of all the actors inclining toward Damascus, Jordan has made the most striking and rapid moves. On 3 October, Jordan’s King Abdullah spoke by telephone with al-Assad for the first time in a decade. The conversation centred on relations between the “brotherly countries and ways to enhance cooperation between them,” according to a readout provided by Jordan. Abdullah reportedly affirmed Jordan’s support for “efforts to preserve Syria’s sovereignty, stability, territorial integrity, and people,” talking points usually conjured up in Moscow and Damascus. The move follows a soft lobbying campaign by Abdullah for the relaxation of international pressure on al-Assad. A marquee feature of that campaign saw Jordan play an instrumental role in pushing forward a plan to revive the Arab Gas Pipeline, which passes through Jordan and Syria. Sanctions waivers from the U.S. were needed to give all parties confidence in the plan (see: Syria Update 20 September 2021), and normalisation has continued apace ever since.

While Jordan’s economic interests have often been invoked to explain Abdullah’s U-turn vis-à-vis al-Assad, other issues may also explain the about-face. Jordan seeks border security, a buffer against drug smuggling, and containment of Iranian militias in Syria’s southern region, a demand it shares with Israel. Jordan also faces acute water insecurity, and Damascus may be able to step in by allowing Jordan access to its own water allotments of the Yarmouk River. Furthermore, some have argued that the moves reflect Abdallah’s ambition to put his personal stamp on regional geopolitics. His eagerness to become an indispensable regional power broker will have grown following a failed palace coup that came to light in April.

Abdullah is not alone in seeking to grant Syria a more fixed role in the regional political firmament. Arab rapprochement has been in train for years, and has rapidly progressed since the beginning of 2021. In March, ministers from Egypt and the UAE described Syria’s eventual return to the Arab League as a public interest that is crucial for maintaining the national security of Arab states. Syrian and UAE trade ministers met on the sidelines of the Dubai Expo 2020 to discuss bilateral relations and potential economic collaboration. The UAE leads Gulf states in vying for an economic and political stake in post-war Syria. The Syrian Foreign Ministry has picked up on these trends, increasingly pushing pan-Arab causes alongside blossoming bilateral relations with its neighbours.

Whether such efforts will lead to the recognition of al-Assad as the sole representative of the Syrian people in the Arab League remains to be seen. This would require hard-to-achieve consensus among member states, who will need to deal with staunch opposition to normalisation, including from Qatar and Saudi Arabia. However, resistance in capitals elsewhere is clearly waning. The U.S. waiver allowing the Arab Gas Pipeline deal is a tacit relaxation of American resistance to normalisation with Damascus. Although a growing number of Syria’s neighbours are acting on their view that functional relations with Syria are an economic and security imperative, it is unclear what the U.S. and other international powers aim to achieve. Observers have criticised the Biden administration’s approach as allowing “full bore legitimation” of al-Assad without demanding concessions in return. Hyperbole aside, the international community is clearly softening on Damascus. Whether decision-makers will manage the coordination and creativity required to demand “behavioural change” remains to be seen.

Whole of Syria Review

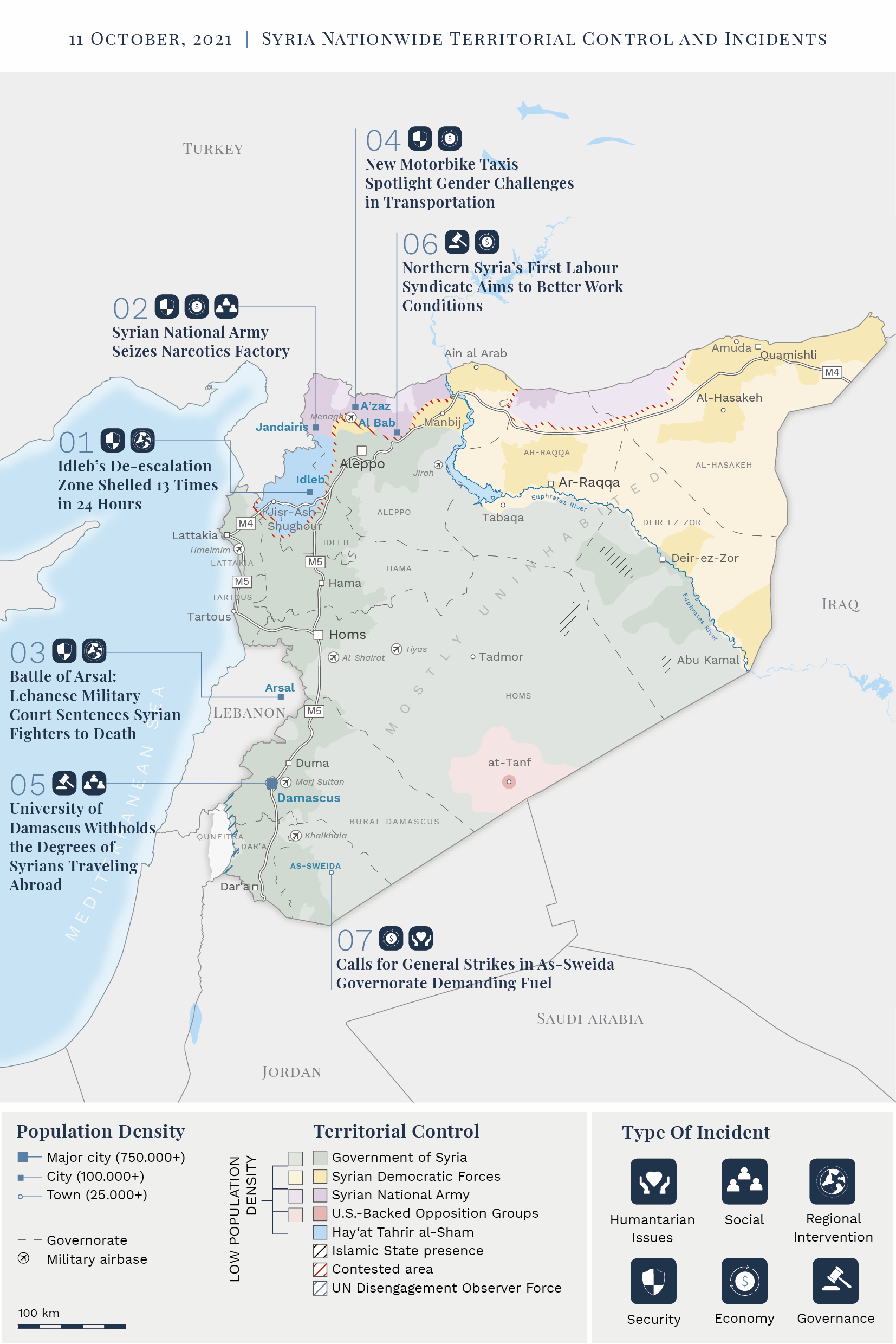

Idleb’s De-escalation Zone Shelled 13 Times in 24 Hours

On 5 October, the deputy head of the Russian Defence Ministry’s Centre for Reconciliation of Opposing Sides in Syria, Vadim Kulit, said in a briefing that Idleb’s de-escalation zone was shelled 13 times on 4 October from “Jabhat al-Nusra” (i.e. Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)) positions, targeting Idleb, Lattakia, Hama, and Aleppo provinces. This came as Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov claimed that the terrorist threat in the region was escalating and called for the “full implementation” of the 2020 Idleb ceasefire agreement between Turkey and Russia (see: Syria Update 9 March 2020).

Despite the ceasefire agreement, bombardment by all parties to the conflict has continued across the de-escalation zone. In September, Russia conducted at least 204 airstrikes across the four provinces, leading to five deaths, and on 2 October, it was reported that Government forces shelled the Jisr-Ash-Shugur district, killing one person and injuring five.

Competing narratives in the ‘frozen conflict’

Russian President Vladimir Putin and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s recent meeting in Sochi has yet to yield any measurable change of tempo in northwest Syria. Indeed, Turkish and Russian officials alluded to a vague commitment to maintaining the status quo in the region (see: Syria Update 4 October 2021). This status quo is marked by instability, regular low-level skirmishes, and bombardments, though not yet at the scale needed to tip the balance toward full-fledged conflict between HTS, the dominant faction in Idleb Governorate, and the Syrian Government. Rather, both sides continue to accuse each other of breaching the ceasefire agreement, while justifying their own actions as retaliation.

The mutual shelling of Idleb and other Turkish zones of influence comes amid heightened talk among analysts and implementers of a possible Turkish-Russian “land swap” in Syria (see: ‘Land Swaps’: Russian-Turkish Territorial Exchanges in Northern Syria). Many continue to posit that Turkey’s desire to carve up Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)-held northeast Syria will encourage Ankara to stand down and allow Russia to recapture the remainder of the M4 highway in southern Idleb, in exchange for Russia’s acquiescence to a Turkish offensive in priority areas of northeast Syria, including Menbij and Ain al-Arab (Kobani). However, few concrete indicators of such an agreement are in evidence — yet. While such a deal remains possible, joint Russian-Turkish patrols have reportedly resumed in northwest Syria following the Sochi meeting, suggesting no major change in the two leaders’ positions regarding conflict lines, which have been frozen for over a year. A Russian Foreign Ministry spokesperson said on 7 October that Turkey and Russia will continue to coordinate diplomatically and militarily to normalise the situation in Syria. Neither side wants to risk full-blown conflict, as Erdogan is above all wary of another surge of refugees amid a rise in anti-Syrian sentiment, while Putin has made the most of warming relations with Turkey to potentially supply it with another S-400 air defence system, driving a wedge between NATO allies.

Syrian National Army Seizes Narcotics Factory

On 3 October, a joint force of the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA) and its military police raided a farm in Jandairis, Afrin District, northern Aleppo, and seized a narcotics factory reportedly belonging to an SNA military commander. This comes amidst a reported rise in the use of narcotics in areas controlled by the SNA and a continued campaign by Turkish authorities and the SNA to crack down on drug-trafficking operations in the region (see: Syria Update 23 August 2021). While the type of narcotics being produced was not specified, it is likely that they were Captagon pills, which, along with hashish, are the most widely used narcotics across Syria.

The continuing drugs trade — a bitter pill

Although ‘narco-entrepreneurs’ affiliated with the Assad regime have been the primary beneficiaries of the Syrian narcotics trade, they are not the only actors profiting from the trade (see: The Syrian Economy at War: Captagon, Hashish, and the Syrian Narco-State). Indeed, individuals and groups in opposition-controlled areas, even SNA affiliates, are still attempting to seize their share of the lucrative drugs business, leading in some cases to armed clashes with security forces. The raid follows the 27 July arrest of Samo Ammar, believed to have been a battalion commander in the Sultan Suleiman Shah Division, for his role in the sale and trade of narcotics in Afrin. He was arrested along with members of his battalion and relatives involved in the trade.

Turkey has attempted to halt cross-border drug flows by implementing crossing restrictions, and authorities have closed down border checkpoints with areas controlled by the Syrian Government. Nevertheless, corruption within the SNA and the potential for significant profit mean that Captagon continues to be shipped across the Turkish border via the northern route to consumer markets elsewhere in the Middle East and, potentially, Europe. Left unchecked, the Syrian drug industry will continue to threaten stability in the broader region.

Battle of Arsal: Lebanese Military Court Sentences Syrian Fighters to Death

On 5 October, media sources reported that a Lebanese military court sentenced four Syrian combatants to death for their involvement in the battle of Arsal in 2014. The Syrian fighters were detained and sentenced based on their involvement with the jihadist group Jabhat al-Nusra, while a fifth was sentenced to life in prison and hard labour. The 2014 battle resulted in the deaths of soldiers in both the Lebanese and Syrian armies and the capture of 42 members of the Lebanese security forces by Jabhat al-Nusra, a precursor group to HTS. The clash began on 2 August 2014 and ended five days later with an unexpected agreement stipulating that the militants move to barren lands outside of the town. Media reports suggested that a prolonged battle would have been difficult for the Lebanese army to sustain as they were battling an unknown number of militants, potentially including residents of the refugee camp in Arsal, which houses around 123,000 people. In many ways, this was an important inflection point in the conflict that cut off militant fundamentalists’ march to the coast.

The shifting blame game

In the post-civil war period, Lebanon has made capital punishment effectively impossible to carry out; it is therefore possible that the four death sentences will be commuted to life in prison. The sentences may serve purposes beyond national security for the Lebanese government. In addition to the deep symbolic importance attached to the battle over Arsal, for years, the Lebanese political class has used the Syrian conflict, spillover violence, and Syrian refugees as scapegoats for its own failings. The need for blame-shifting has only grown as Lebanon’s freefall has become more dire. The international community should be aware that anti-Syrian sentiment will continue to grow as the situation in Lebanon worsens, and the pressure to drive Syrians back to Syria will increase as regional normalisation efforts deepen.

New Motorbike Taxis Spotlight Gender Challenges in Transportation

A new motorbike taxi service in A’zaz city is gaining steam as a public transit alternative amid rising fuel and transportation costs. With fuel costs tied to the Turkish lira (TRY), one litre of premium fuel now costs around TRY 6.80 (roughly 0.77 USD) in northern Aleppo, making transportation costs increasingly prohibitive for lower-income residents. Motorbike rides cost upwards of TRY 10 (1.13 USD), providing a more affordable alternative to increasingly costly private taxis and largely non-existent public transportation options. The motorbike service is currently only available in A’zaz city.

Stopgap solutions, structural problems

While the new service provides a much-needed transportation alternative and new livelihood opportunities, it entails risks for mobility and gender-equitable access. The service is likely less accessible to female users, who may be unwilling or unable to ride as a passenger on a motorbike driven by a male operator. The gendered impacts of Syria’s ongoing transportation crisis are increasingly apparent. Security considerations have commonly pushed women to opt for private transportation where possible; however, rising costs increasingly hinder their access to both safe and affordable transportation. In the absence of viable alternatives, women risk being further crowded out of transit systems and losing access altogether, especially in rural areas where options are especially limited. Such a development will impede women’s ability to participate in local commerce or access aid services and programmes, which tend to be concentrated in city centres and urban areas.

Increased motorbike traffic likewise poses a risk to public safety, especially as safety regulations for the new service remain unclear. Road conditions in northern Aleppo are infamously poor and enforcement of traffic regulations for motorbikes is generally lax. Traffic-related deaths have been on the rise in more restive areas of northern Syria recently, with particularly high rates of accidents involving motorbikes. Motorbikes have also commonly been used to detonate roadside bombs in northern Aleppo in recent years, calling into question the longevity of such a service in the event of increased attacks against Turkish installations or other security apparatuses.

University of Damascus Withholds the Degrees of Syrians Traveling Abroad

On 3 October, media sources reported that the University of Damascus will condition the award of university certificates and degrees on the presentation of students’ travel records and documentation of their immigration status. According to the reports, the university will withhold transcripts and graduation certificates until students obtain a detailed statement from immigration authorities explaining any movements to and from Syria. Students have denounced the decision, claiming that it restricts the movement of Syrian citizens and forces students to pay hefty bribes in order to obtain their papers.

Degrees deferred

Through the move, the university is effectively holding students hostage in an attempt to stem brain drain and close a loophole used by many to defer military conscription. Students are generally eligible for conscription waivers while pursuing degrees, and many students evade service altogether by leaving the country immediately after graduation. While the university itself cannot prevent students from fleeing Syria, the decision has the power to substantially complicate the process. There is a fear that travel information submitted to universities could be collected and used as evidence against students who intend to flee Syria for more stable contexts. Furthermore, donors and programme implementers should view the decision as an indication of further interference by the Syrian Government in the education sector.

Northern Syria’s First Labour Syndicate Aims to Better Work Conditions

On 3 October, the Free Labour Assembly established northern Aleppo’s first labour syndicate in Al-Bab city. Abdul Salam Najjar, the appointed president of the syndicate, stated that its primary objective is to attain rights and better wages for workers and create jobs by encouraging factory and small business owners to establish new enterprises. The initiative was not sponsored by the local government, and coordination between the syndicate and local governance structures remains unclear.

Labour pains

Syria’s labour force has been severely undermined throughout the conflict for a variety of reasons, not least the flight of industrial investment and the destruction of infrastructure. According to Najjar, the vast majority of working-age residents in Al-Bab and surrounding towns are unemployed. Those who are employed face harsh working conditions including long working hours (often reaching 14-15 hours per day) and rock-bottom daily wages, seldom exceeding TRY 30 (3.36 USD).

A representative body for the labour force in northern Syria may play a role in spurring job creation and securing workers’ rights. However, the absence of a legal framework to regulate the relationship between the syndicate, local government, and employers will limit its effectiveness. The new syndicate’s impact will also be blunted by the sometimes contradictory employment regulations imposed by other sector- or location-specific syndicates across northern Syria.

Calls for General Strikes in As-Sweida Governorate Demanding Fuel

On 3 October, multiple local social media pages and activists in As-Sweida Governorate called to push the Government to increase subsidised fuel allocations from 50 to 400 litres per family during winter. Protestors gathered in front of the As-Sweida municipality building where the mayor promised to communicate their demands to the appropriate government officials, while reiterating the challenges in meeting such demands. Several local shop and business owners announced they would close their businesses until the demands are met.

Struggling for the basics

This is the latest in a series of popular movements to erupt in As-Sweida over the last two years. In the main, such movements have been largely confined to issues related to household economics and livelihoods, as in other Government-controlled areas (see: Syria Update 15 June 2020). Nominally apolitical movements such as these have enabled broader participation, yet they face long odds of meaningfully improving local service provision. As frustration grows across Syria, communities in Government-controlled areas may find it increasingly difficult to avoid overtly political activity or directly challenge the Government of Syria, which risks violent crackdown and hostile repression.

Open-Source Annex

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below..

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

Northern Syria water crisis affects 5 million people: UN

What Does It Say? Water shortages in northern Syria have deprived around five million people of adequate access to clean water.

Reading Between the Lines: Among other issues, the crisis could lead to hygiene-related complications and increase the spread of waterborne diseases as well as COVID-19.

Third tanker of Hezbollah-run Iranian oil reaches Syria en route to Lebanon

What Does It Say? The third tanker carrying Iranian oil to Lebanon via Syria, facilitated by Hezbollah, has docked at Baniyas port in Syria.

Reading Between the Lines: Oil continues to be delivered to Lebanon overland through Syria despite sanctions on Iranian oil.

What Does It Say? Jordan’s Director of Intelligence stated that Jordan must be realistic and acknowledge that its neighbour has a significant and multifaceted impact on the country.

Reading Between the Lines: Jordan is keen to reinitiate relations with Damascus for a variety of reasons, not least the threat of Iranian-backed forces along its northern border. Jordan’s hasty return to Damascus has been the most significant rapprochement to date.

Iran Pressures Syria as it Fails to Implement Long-Standing Agreements

What Does It Say? Iran is becoming increasingly frustrated with the Syrian Government’s lack of commitment to bilateral agreements and partiality toward Russia.

Reading Between the Lines: Although the Syrian Government can be expected to place its own interests above all else, the failure of such agreements to yield material benefits for Iran is in part due to incapacity and isolation on the part of Syria.

Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan reach an agreement to reinstate shared power network

What Does It Say? Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon have agreed to reinstate the power network running from Jordan to Syria and Lebanon.

Reading Between the Lines: Lebanon and Syria are both keen to find regional solutions to debilitating energy shortages, while the agreement calls into question the U.S’s willingness to actually apply penalties under the Caesar sanctions to regional actors, many of which are nominal allies or partners.

Why Washington has provided King Abdullah with political cover to engage the Assad regime

What Does It Say? Jordan suggests engaging Syria bilaterally to undergo political change may be more effective than forcing change through other avenues.

Reading Between the Lines: A decade of violence has shown that the Syrian Government will not be strong-armed into changing its approach, however it is vital for the international community to determine how to convert leverage into concessions without full normalisation.