In-Depth Analysis

On 13 and 14 October, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu and Defense Minister Hulusi Akar stated that Turkey will “do what is necessary for its security” after what they described as an increase in cross-border attacks by the Syrian Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG), the backbone of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). Days earlier, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan had raised the alarm after a reported YPG attack killed two Turkish police in northern Syria’s A’zaz. Erdogan described the attack and another incident in which projectiles landed in the southern Gaziantep province as “the final straw” for Ankara.

Déjà vu all over again

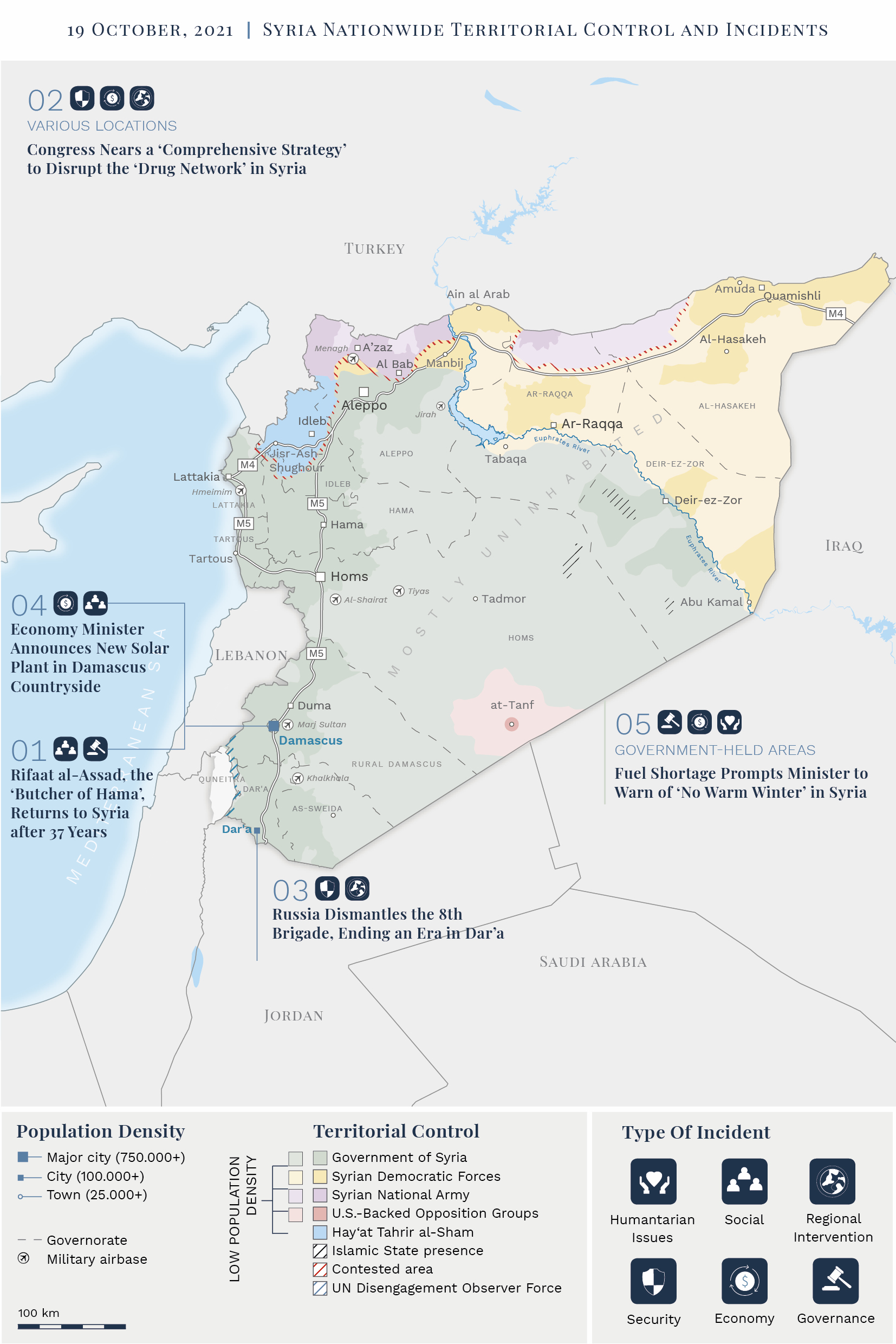

Veterans of the Syria crisis response will be familiar with such statements. More than 18 months since the conflict ground to a halt in the country (see: Syria Update 9 March 2020), the rising pitch of warnings from Ankara intensifies speculation over the military trajectory of northern Syria. Read in that context, the statements are a reminder of Turkey’s continued interest in the implementation of a 30 km buffer zone stretching across Syria’s northern frontier, a project that it has repeatedly framed as a national security imperative needed to drive the SDF away from Turkish territory. For the time being, Russia stands in the way of full implementation of such a plan, as its military presence lends direct support to the SDF in key areas of Turkish interest in northern Syria. These include Manbij, now a burgeoning hub of crossline commercial trade, and the symbolically important Ain al Arab (Kobani) region to its east — both key communities to the Autonomous Administration. Also in Turkey’s sights is the SDF enclave of Tell Rifaat in northern Aleppo, which is frequently used as a launch pad for attacks on opposition-held areas to its north (see territorial control map on page 3). While it is difficult to forecast Ankara’s next moves, precedent shows that Turkey is willing to launch military operations in Syria, and its increasingly bellicose language suggests that its patience is flagging.

The rhetorical escalation comes two weeks after the Sochi meeting between Erdogan and his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin. Beyond a vague commitment to the “status quo,” the closed-door discussions have so far produced no concrete outcomes. Since the meeting, analysts, donors, and implementers have speculated as to whether it will precipitate renewed military offensives in Syria by Turkey, Russia, or both. Overlapping military interventions in Syria are a central element of the regional partnership between Turkey and Russia. By coordinating the suspension of support to local forces on the ground in Syria, each has succeeded in clearing the way for the other to capture strategic areas. Since 2016, virtually every major military operation by one has coincided with a commensurate operation by the other (see: ‘Land Swaps’: Russian-Turkish Territorial Exchanges in Northern Syria).

It is important to note that military activities across northern Syria have not, as of writing, significantly escalated, despite continuing bombardment by Russia in the northwest and threats from Ankara. Beyond its rhetorical posturing, Turkey has given few unambiguous signs that it is currently ready for an offensive, yet changes are taking place. The rhetorical upshift comes after reports that five Turkish generals have resigned, according to some but not all sources, in protest of Turkey’s military approach to Syria. Some have speculated that the generals’ resignations may free Ankara’s hand for a more unrestrained approach to Syria.

What does Russia want?

Since the Sochi meeting, Russia has continued to bombard Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) positions in opposition-held Idleb, particularly in the M4 and the Jabal al-Zawiya region. Moscow and its Damascus allies are eager to restore full unilateral control over the strategic M4 highway in southern Idleb. Turkey’s implicit support for the Syrian opposition impedes this, leading many to ask whether another tit-for-tat ‘land swap’ is on the horizon. However, Russia has heightened its rhetoric as well, and it blames Turkey for failing to live up to its commitments as stipulated in the 2020 memorandum on Idleb, which called for a plan to isolate ‘radical’ groups including HTS from ‘moderate’ opposition factions. Turkey may factor in Moscow’s ambition to pressure the SDF to cut a deal with Damascus, which it views to as a way of neutralising the SDF and bringing the Syrian Government greater energy security. Russia may countenance a Turkish incursion in northeast Syria as a means of instigating such negotiations, as seen in the wake of the Peace Spring offensive (see: Syria Update 9-15 October 2019 and 19-22 October 2019).

Agreement between Moscow and Ankara is likely needed for a major offensive to be launched. Less certain is the view from Washington. The U.S. is the most important backer of the SDF, and to an extent, it also stands in the way of a potential Turkish incursion, although the American military presence is now largely concentrated outside Turkey’s proposed buffer zone. The U.S. has offered its condolences to the families of the Turkish police officers killed in Syria, yet there are no signs the U.S. is preparing to forsake its SDF partners in northeast Syria by green-lighting a Turkish incursion, as it did by withdrawing from border areas in 2019 under the Donald Trump administration (see: Syria Update 2-8 October 2019). Ankara does not necessarily require say-so from Washington before launching a new offensive, but doing so against the Biden administration’s wishes would inflame an already tenuous relationship.

Impact

To date, Turkey has launched four major military offensives in Syria: Euphrates Shield (2016), Olive Branch (2018), Peace Spring (2019), and Spring Shield (2020). In the lead-up to each offensive, Turkey vocalised its concerns about violations of red lines and the growing influence of YPG fighters close to its borders. A fifth offensive — potentially waged in northeast Syria or Tell Rifaat — would have a calamitous humanitarian impact. If launched in northeast Syria, civilians in affected areas would be displaced to population centres outside the 30 km buffer zone, such as Ar-Raqqa. Many are likely to flee to the Kurdistan region of Iraq. The limited scale of returns since the 2019 Peace Spring offensive demonstrates that civilians displaced from northeast Syria will face major impediments to return to areas seized by Turkish-backed forces. Moreover, the SDF will likely divert resources from operations to counter the Islamic State and local security activities in other parts of eastern Syria to shore up defences on frontlines near the Turkish border.

In parallel, an offensive by Turkey is likely to trigger Russian and Government of Syria military actions in southern Idleb, either as part of a tacit agreement with Turkey, or in retaliation against it. While their primary focus is the Jabal al-Zawiya region, displacement from surrounding areas is likely to be significant. At the height of the winter 2019-2020 campaign by Russia and the Government of Syria, roughly one million people were displaced toward the Turkish border. Winter conditions and a lack of shelter exacerbated urgent humanitarian needs, and housing stock remains an issue in the region. Turkey — wary of a refugee influx — threatened at that time to open its western border to allow migrants to move on to Europe. It is possible that this scenario will repeat itself this winter.

Whole of Syria Review

Rifaat al-Assad, the ‘Butcher of Hama’, Returns to Syria after 37 Years

On 7 October, Rifaat al-Assad, the younger brother of Hafez al-Assad, reportedly returned to Syria from Belarus, only months after being convicted of misappropriating Syrian public funds and money laundering by French courts. He was sentenced to four years in prison in June 2020, a verdict that was upheld by the Paris appeals court on 9 September 2021. Rifaat left Syria in 1984 after a failed coup attempt against his brother, and has since lived in exile, largely in Spain and France, while amassing a property empire with an estimated value of 90 million EUR. According to his lawyer, Rifaat had been living with Syrian friends in Minsk, Belarus since July 2021.

To err is (in)human

In allowing Rifaat to return to Syria, Bashar al-Assad has professedly forgiven “all that Rifaat al-Assad has done.” The desire to avoid the humiliation of having a family member imprisoned abroad apparently outweighs the drawbacks of allowing a widely despised figure who was previously considered a contender for power to return. It is therefore a testament to Bashar al-Assad’s confidence in his hegemony. Rifaat is widely known and despised as the ‘butcher of Hama’, responsible for the 1982 Hama massacre in which tens of thousands of civilians were killed by military bombardment. Despite his exile, he was officially Vice President of Syria between 1984 and 1998, and proclaimed himself the legitimate heir to his brother Hafez in 2000, calling Bashar’s elevation to the presidency ‘unconstitutional’. In 2011, as the uprising gathered pace, Rifaat supported the opposition and publicly called on Bashar al-Assad to “vacate his position,” but as the war turned in the Syrian Government’s favour, he grew silent. Following his return, he will play no political or social role in Syria, according to pro-Government sources.

Many have highlighted the inconsistency between the liberal, Western values espoused by France and the fact that al-Assad was able to live there in comfort and luxury for decades. Similarly, a war-crimes investigation into Rifaat opened in Switzerland in 2013 has repeatedly stalled, reportedly due to political pressure from above. It is particularly jarring that Rifaat’s return comes in the wake of Syria’s readmission to Interpol (see: Syria Update 11 October 2021), which gives the Assad regime increased powers to target political dissidents abroad. That Rifaat first fled Paris to Minsk, Belarus, is also of note. The head of another ‘pariah state’ and widely referred to as ‘Europe’s last dictator’, President of Belarus Alexander Lukashenko has quietly cultivated military and economic links to the Assad regime, and even sent observers to Syria to monitor the May 2021 presidential election. Not only is Belarus a link between the Assad regime and the outside world, it has also grown in importance as a migration pathway for Syrian migrants fleeing their country.

Indignation at impunity for Syria’s elite has grown more vocal after a video circulated earlier this month showing Ali Makhlouf — Bashar al-Assad’s cousin and the son of Rami Makhlouf, the regime’s erstwhile financier — driving a $300,000 Ferrari in Beverly Hills, where he claimed he was “doing an internship.”

Congress Nears a ‘Comprehensive Strategy’ to Disrupt the ‘Drug Network’ in Syria

On October 11, the Arabic-language newspaper Asharq Al-Awsat quoted an unnamed U.S. State Department Spokesperson, who stated that the U.S. government is prioritising efforts to combat drug trafficking and transnational organised crime in Syria. While the newspaper reported no specific details concerning an American counter-narcotics strategy in Syria, a concerted approach to interrupt drug networks in Syria is included in the U.S.’s 2022 defence appropriations bill, which is expected to become law by the end of the year. The bill states:

(1) the captagon trade linked to the regime of Bashar al-Assad in Syria is a transnational security threat; and (that)

(2) the United States should develop and implement an interagency strategy to deny, degrade, and dismantle Assad-linked narcotics production and trafficking networks.”

Another battle in the war on drugs

This development constitutes another effort to hamstring the Assad regime by undermining its illicit financial base. If the plan is to go forward, the U.S. must compensate for its limited direct access to Syria. This will entail considerable challenges around data collection. It will also require a complex, multinational approach to understand networks involved in the sprawling, regional narcotics industry (see: The Syrian Economy at War: Captagon, Hashish, and the Syrian Narco-State).

Russia Dismantles the 8th Brigade, Ending an Era in Dar’a

On 11 October, media sources reported that the Syrian Government’s security committee will dismantle the Russian-backed 8th Brigade, which currently holds sway in portions of Dar’a Governorate, and integrate it into the Government’s own command structure through the Military Intelligence Directorate. This comes in the wake of a new reconciliation agreement that required the handover of individual weapons by Dar’a opposition fighters, as well as a greater presence of Government military personnel throughout the south (see: Syria Update 2 August 2021).

Dar’a is down, Damascus is up

The 8th Brigade’s dissolution spells the end of an era in southern Syria. The move is the most consequential to date in the Syrian Government’s continuing efforts to quell resistance in hotbeds of unrest in the restive south. The 8th Brigade has been a key player in the region since its reconciliation in 2018, and the new military formation offered hope to former opposition fighters who preferred to stay in their communities rather than displace to northern Syria with irreconcilable fighters and dissidents (see: Security Archipelago: Security Fragmentation in Dar’a Governorate). Through the group, Russia has provided a semi-independent alternative to full reintegration into the Syrian Government’s command structure. Now, the group’s operating space has disappeared, and 8th Brigade commander Ahmed al-Oudeh has, according to local sources, fled to Jordan, fearful of the expanding reach of Syrian intelligence in areas where his forces were, until recently, dominant (see: Syria Update 29 June 2020). However, the developments may be welcome news in Amman, which has pushed for greater stability on its northern border with Syria (see: Syria Update 11 October 2021). Looking ahead, by tightening its grip on the region, the Government of Syria will be able to impose heightened restrictions on communities and control former dissidents with impunity. However, assassinations and other forms of low-level insurgent attacks are likely to continue.

Economy Minister Announces New Solar Plant in Damascus Countryside

On 3 October, Syrian Minister of Economy and Foreign Trade Mohammad Samer al-Khalil announced a new contract with an unnamed Emirati company to establish a solar power plant in the Damascus countryside. The contract is being touted as the largest investment in Syria’s energy sector to date. The company is one of several foreign entities eyeing investment in Syria’s energy sector in recent years. According to other reports, contracts were recently awarded to Russian and Iranian companies to repair power plants in Harasta and Mhardeh. Syria’s electricity grid has been heavily damaged by the conflict and requires wide-scale repairs and maintenance. Power outages have become the new norm across Government- and opposition-controlled areas alike.

Investment in Syria’s energy sector remains low despite new incentives to encourage Syrian households to transition to solar energy and to attract foreign investment. The latter is hindered by Western sanctions on reconstruction in Syria, which greatly limits avenues for importing hard infrastructure and equipment. During the October 3 press briefing, al-Khalil openly expressed the Syrian Government’s willingness to facilitate companies’ successful circumvention of sanctions by allowing foreign companies ‘fearful of sanctions’ to sign contracts with an alias.

Brighter days ahead?

The new solar power plant will provide 300 megawatts of power, a drop in the bucket against a crippling power deficit and dysfunctional electricity grid. Syria’s energy sector has not, until now, received the large-scale investment needed to substantially offset these needs. This is partly due to doubts around the profitability of such investments: Government incentives to reel in investors could be overwritten or undermined by future laws, and profits would likely be channelled through the Government’s own coffers — and could remain mired there. Indeed, the fact that the sector has not witnessed large-scale investment by Syria’s wartime nouveaux riches likely hints at a limited return on investment.

Energy access is increasingly uneven across social, economic, and political strata. Prevented from investing in hard rehabilitation of Syria’s electricity grid by donor red lines, aid programmers increasingly opt to invest in alternative energy sources for their own facilities, or, in the case of northwest Syria, facilitate Turkish privatisation of the local energy sector. While several aid projects have focused on securing energy alternatives for hospitals and other service facilities, such support seldom addresses energy needs at the household level, where residents often must decide between hefty upfront costs for solar equipment or dependency on increasingly scarce fuel.

Fuel Shortage Prompts Minister to Warn of ‘No Warm Winter’ in Syria

On 9 October, Syrian Minister of Electricity Ghassan al-Zamil reportedly warned that there will be no “warm winter in Syria this year” due to severe fuel and gas shortages. He claimed, however, that there will be a noticeable improvement in power generation in 2022, and stated that in 2023, Syria’s electricity generation levels will return to pre-conflict levels. Amid scarcity, local sources report that Syrians continue to resort to wood as an alternate heating source. However, wood fuel prices have reportedly increased with each passing winter: and one ton of firewood costs approximately 700,000 SYP in As-Sweida ($199.43). The minister went on to say that while repair works are being made to the electrical grid, it will be a while yet before the population notices any difference. In August, media sources reported that the Mahruqat Company would supply a significantly smaller quantity of heating oil to families than in previous years (50 litres instead of 100 litres) across all governorates.

Honesty is cold comfort

According to media sources, only around 25,000 out of 350,000 people (7 percent) who registered for their allotted 50 litres of heating oil have actually received it. Frustration at the paltry distribution, which began in August, is mounting. Nowhere is this more evident than in As-Sweida, where protests erupted in front of the municipality following the 3 October announcement regarding cuts to allocations (see: Syria Update October 11). Media sources have reported that local elites have monopolised fuel smuggling, benefiting at the people’s expense.

It is notable that the Government has recently resorted to surprisingly honest rhetoric regarding the food and energy sectors. Such statements prepare Syrians for hardship ahead, and they may indicate that food and energy are sectors in which the Syrian Government is eager to solicit international support — and may be willing to make concessions. For the time being, the international community, donors, and implementing organisations should prepare to take appropriate measures in light of growing hardship, including by scaling up efforts to winterization projects.

Open-Source Annex

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below..

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

EU Extends Sanctions Over Use of Chemical Weapons for a Year

What does it say? The European Council has renewed its sanctions targeting entities and individuals responsible for the proliferation and use of chemical weapons, as well as those providing financial, material, or technical support.

Reading between the lines: The EU’s restrictive measures, including those related to the proliferation of chemical weapons currently targeting 15 individuals and two entities linked to the Syrian regime and Russia, remain one of the few remaining tools in dealing with Syria, especially in the absence of a clear Western strategy.

Investigating What Assad’s Regime Did with Money to Rebuild Syria

What does it say? The investigation reveals that revenues raised through the “reconstruction tax” imposed by the Syrian Government on the pretext of compensating for the homes destroyed in the war were diverted, and some were used for military purposes.

Reading between the lines: With Western sanctions mounting since 2012, the Government quickly began seeking domestic revenue-generating alternatives; it is estimated that 5 to 10 percent of government finances since 2013 have been derived from the “reconstruction tax.”

Turkish intelligence helped Iraq capture Islamic State leader

What does it say? A joint Iraqi-Turkish intelligence operation resulted in the capture of a deputy to the deceased Islamic State leader Abu-Bakr Al-Bagdadi.

Reading between the lines: Senior IS leader Sami Jasim, who had been hiding in northwest Syria, was announced captured in an external operation by Iraqi intelligence, aided by Turkish intelligence, signalling increased regional coordination against what remains of IS. While factions controlling northwestern Syria have been hostile toward IS, it is unclear whether any Syrian factions were involved.

Who really controls the Syrian economy? The Syrian regime or its loyal businessmen?

What does it say? The Syrian Government’s recent economic measures, while deemed necessary for the regime’s survival, were also designed to satisfy the demands of loyal businessmen, raising doubts over the regime’s dominance over its close business circles.

Reading between the lines: The Syrian regime’s current economic policy revolves around compensating its allies, including local businessmen. These businessmen now have two options: 1) leave Syria with whatever money they can carry; or 2) remain, obey, and try to shift power dynamics in their favour.

Biden’s Inaction on Syria Risks Normalizing Assad—and His Crimes

What does it say? The article expresses an increasingly vocalised point that as the U.S. looks the other way, the Syrian regime is gradually returning to the world stage.

Reading between the lines: The ongoing re-engagement with the Assad regime, championed by Jordan with increasing regional support, and tolerated by the West, signals a gradual shift toward the adoption of a “behavioural change” approach; however, the regime is reaping the benefits of re-engagement without showing any change in behaviour. The West should make it multilateral coordination a clear priority.

Patients pay double bills for laboratory tests in Quamishli

What does it say? Residents of Quamishli suffer from the high cost of medical tests and long waits at the city’s medical centre. Due to the governorate’s lack of medical facilities, people travelling from rural areas are also burdened with transportation costs.

Reading between the lines: The reasons for the exorbitant cost of medical treatment in Quamishli include the cost of laboratory analysis instruments, which are purchased in US dollars. The cost of running medical facilities continues to increase as the Syrian pound depreciates.

The New Child Rights Law in Syria will not protect children

What does it say? Two months after issuing law No. 21 of 2021, which expands the protection and rights of children, its enforcement on the ground is still very limited. This suggests that the law was designed to create the appearance of progress on human rights rather than have any actual impact on children’s protection.

Reading between the lines: Several aspects of the law remain ambiguous, including key areas like a mother’s ability to pass on nationality to her children. Others include the possibility for child marriage, protecting children from military recruitment, and the possibltiy of labour exploitation.

Syria’s Bashar al-Assad Returns to World Stage in Defeat for US, Win for its Foes

What does it say? The article outlines how after ten years precarious years for Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, the pariah leader is closer than ever to making a comeback on the world stage. Most countries are motivated to accept this by a variety of factors, including regional stability, refugee repatriation, and participation in the country’s reconstruction.

Reading between the lines: On the other hand, normalisation faces hurdles, such as the strong influence of many local and international actors in Syria, and the U.S.’s ability to prevent a full victory for al-Assad and his allies.

Reconciliation Deals and Intermediaries in Syria

What does it say? Throughout the conflict, the Government of Syria has relied on local intermediaries to strike reconciliation deals. Russia and Iran have also created their own networks of local intermediaries to cultivate their interests.

Reading between the lines: The majority of intermediaries mapped in the study are located in Rural Damascus and Dar’a, which reflects their role in facilitating the Government’s return to these areas. However, after the Government had re-asserted its control, many of them were assassinated, detained, or marginalised.

Wheat-to-Bread Processing Facilities Mapping

What does it say? The report maps and monitors processing facilities in the wheat flour to bread value chain in northeast Syria. Facilities were generally found to be functioning at 50 percent of their full capacity, despite the fact that overall bread production increased by 28 percent compared to March 2021. The price of subsidised bread almost doubled between March and July 2021.

Reading between the lines: Three main factors directly affect the availability of bread: flour shortages, displacement-driven population increases, and low production capacity.