Executive Summary

This report uses regional case studies to identify programming opportunities and entry points for empowering and supporting LGBTQ+ Syrians. It finds that a lack of donor emphasis has overlapped with significant protection, community acceptance, legal, and social stigma issues to complicate programming that is sensitive to LGBTQ+ concerns. It argues that capacity building and support for local and regional organisations, measures to improve safety and protection, and a focus on health and sexual and gender identity (SOGI) education are approaches that can be taken in the near term to aid LGBTQ+ Syrians. In the long term, a focus on advocacy and awareness will also be important. All such steps must, to the extent possible, be carried out within the spirit of localisation, and a do no harm approach must inform all activities.

Introduction

Since mid-2021, the Syria crisis response has devoted increasing attention to the feasibility of support for LGBTQ+-sensitive projects. In response to the growing visibility of LGBTQ+ aspects of the humanitarian crisis in Syria, many donors have expressed a willingness to contemplate such activities, but have found it difficult to operationalise that desire. Understandably, many decision-makers have taken stock of imposing conditions inside Syria and in major refugee-hosting states and have concluded that such projects, though long-neglected and deserving of greater attention, are impractical, overly complex, or even dangerous to partners and beneficiaries alike. The Government of Syria effectively criminalises homosexuality, and tight controls on civic space in Syria mean that overt advocacy for LGBTQ+ rights poses a very real risk to campaigners, implementers, and beneficiaries. Aid actors, therefore, face a significant challenge in identifying relief activities that are both realistic and can improve material conditions for LGBTQ+ Syrians.

This report proposes practical first steps to bridge these gaps. It builds on our previous assessment of LGBTQ+ experiences of the conflict in Syria (see: LGBTQ+ Syria: Experiences, Challenges, and Priorities for the Aid Sector) and draws on lessons learned from regional contexts to identify entry points to facilitate LGBTQ+-sensitive project implementation in Syria, refugee-host states, and the region more broadly. Achieving sustainable progress for LGBTQ+ Syrians is a formidable challenge that will be realised not in a single project cycle, but in the long term. It will require cautious localisation and support for civil society wherever possible, in addition to advocacy for the rights of LGBTQ+ persons.

Key Findings

- Empowering LGBTQ+ Syrians is a long-term ambition that requires overcoming social and governmental hostility, strong advocacy, and concrete programming wherever possible.

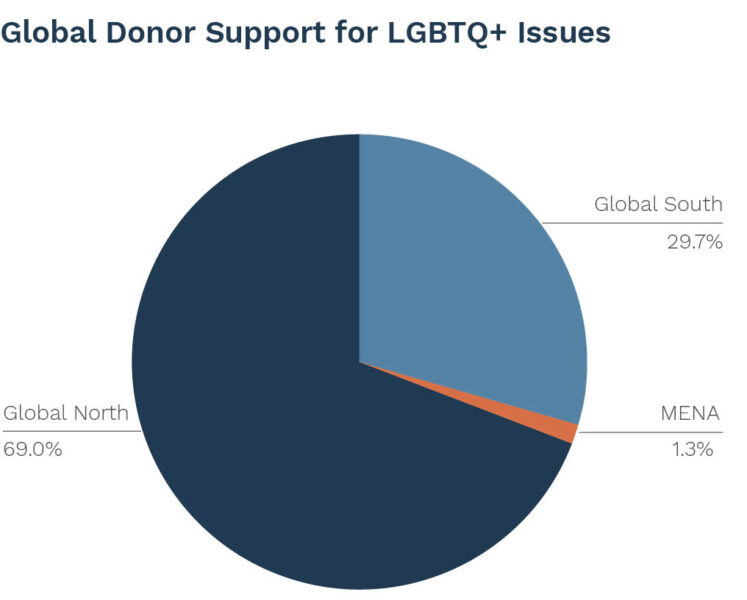

- Attitudes toward LGBTQ+ persons in Syria reflect and affect those in the wider region; aid programming has seldom addressed these concerns. Donor support for the LGBTQ+ community has largely been de-prioritised, a reality that is visible in a lack of monetary support. A mere 1.3% of global development aid and private foundation funding targeting LGBTQ+ concerns is allocated to the MENA region, meaning that many of the most vulnerable are among the least served.

- LGBTQ+ initiatives are a fundamental part of broader civil society in Syria. Experiences in comparable contexts demonstrate that LGBTQ+ initiatives succeed in part because civil society space already exists. Likewise, support to LGBTQ+ programming strengthens civil society as a whole. Both objectives can be pursued in concert.

- Where progress has been made by LGBTQ+ activists in the region, it has largely been the result of partnerships under a broader human rights framework. To date, successes have constituted piecemeal improvements, and the wholesale changes needed to protect the rights of the LGBTQ+ community remain elusive.

- There is often a tension in aid programming between mainstreaming an issue and a targeted focus on the affected communities and beneficiaries. Both approaches are needed to ensure that LGBTQ+ populations are not marginalised within the wider aid response and that their specific vulnerabilities and needs are addressed.

Recommendations

- An LGBTQ+-sensitive aid response in Syria must encompass two distinct approaches: advocacy (long-term) and direct assistance (short-term), which includes funding targeted to LGBTQ+-specific projects and organisations.

- In view of access challenges in Syria itself, greater opportunities to reach and empower LGBTQ+ Syrians may be possible through a focus on other countries in the region, particularly those with more vibrant civil society or large numbers of Syrian refugees.

- Partnership between LGBTQ+ groups in the Global North can provide a key entry point for capacity building and the training of individuals and groups in Syria and the MENA region to professionalise, organise, and advocate. Empowering local organisations to act improves the context sensitivity of their activities and decreases the risk to donors. While donors and partners are rightly suspicious of capacity training after a decade of such activities, it is important that they recognise that LGBTQ+ issues have not benefited from such programming in the past.

- Key programmatic entry points include initiatives to raise awareness and carry out advocacy through existing aid frameworks and the media, as well as capacity building, protection and safety, and health care.

- Above all else, it is vital to do no harm. Programming should be undertaken with an understanding of key contextual considerations, inclusive conflict-sensitivity frameworks, and in dialogue with LGBTQ+ individuals and communities on the ground.

LGBTQ+ Rights in a Global Context: Progress and Challenges

The preeminent challenges facing LGBTQ+ advocates vary according to context, and advocacy must be adapted accordingly. In regions such as Western Europe and North America, advocates’ attention has focused on broader social acceptance, marriage equality, and employment non-discrimination, while elsewhere in the world, activists have tended to focus on more fundamental concerns, particularly the repeal of laws that criminalise homosexuality.[1]Ashley Currier, “Out in Africa”. University of Minnesota Press (2012): https://www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/out-in-africa In the past two decades, many countries in the Global South have repealed sodomy laws or decriminalised homosexuality,[2]These include Armenia, Costa Rica, Mozambique, Nepal, and Nicaragua, among others. and in 2008, 96 member states signed on to a first-of-its-kind UN declaration on LGBTQ+ rights that condemns discrimination and violence on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. However, positive developments such as these have been offset by a flurry of discriminatory laws and episodes of violence directed against LGBTQ+ individuals. Some nations have re-criminalised homosexuality, making same-sex relations illegal in 72 countries.[3]India is among the countries to have re-criminalised homosexuality, while severe anti-LGBTQ+ laws have been introduced in Russia, Nigeria, and elsewhere. Even where same-sex relations are not illegal, social attitudes continue to provoke hostility towards LGBTQ+ individuals.[4]Jacob Poushter and Nicholas Kent, “The Global Divide on Homosexuality Persists”. Pew Research Center (2020):

https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2020/06/25/global-divide-on-homosexuality-persists/

Challenges such as these are particularly stark in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), where a majority of countries outlaw same-sex relations through overt criminalisation or in practice through vague “morality” laws.[5]“Audacity in Adversity: LGBT Activism in the Middle East and North Africa”. Human Rights Watch (2018): … Continue reading No Arab country prohibits legal discrimination on the grounds of sexual or gender identity, and no such state has a standardised procedure for trans people to change their gender on official documentation, meaning that trans people are vulnerable to harassment and persecution whenever they must show their documents.[6]Ibid. Some countries have laws that criminalise gender nonconformity. Despite the need for a regionalised and indeed localised response to specific LGBTQ+ needs in a given context, donor-led crisis responses and development projects have approached these issues tenuously at best.

Missing in Action: The Donor-Led LGBTQ+ Aid Response

Development agencies in the Global North generally profess a strong commitment to LGBTQ+ rights.[7]“Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity SOGI”, Council of Europe: https://www.coe.int/en/web/sogi In practice, this is seldom apparent in programme selection or implementation. In general, LGBTQ+ issues are not viewed as a priority for donor governments, irrespective of their social commitments domestically or the emergence of inclusive foreign policy agendas. Regrettably, prejudice or misunderstanding among staff and personnel within implementing organisations and donor agencies and a limited awareness of LGBTQ+ issues in general are sometimes barriers to the effective prioritisation of these issues.[8]“Avenues for Donors to Promote Sexuality and Gender Justice”. Institute of Development Studies (2016): https://rb.gy/y0ogc5 The potential for controversy in some settings, including Syria, only increases donors’ reluctance to engage. To the limited extent they are operationalised at all, LGBTQ+ concerns are often retrofitted onto an existing portfolio, and they therefore lack the strategic foresight needed to create lasting change. While there are important steps to be made in the mainstreaming of LGBTQ+ concerns across sectors in Syria and elsewhere, more can be done for context-sensitive implementation. Current approaches in public health, for instance, have often been simplistic and superficial, and LGBTQ+ programmes largely cater to the perceived sexual and public health needs of men who have sex with men, to the exclusion of other beneficiaries.[9]Amy Lind, “Development, Sexual Rights and Global Governance”. Routledge (2010): … Continue reading

In Aid Work, Money is the Measure of All Things

To the extent that funding reflects donor priorities, a failure to engage in LGBTQ+ programming is evident. Nowhere is this lack of funding more acute than in the Middle East. The 2017-2018 Global Resources Report, published by Funders for LGBTQ+ Issues and the Global Philanthropy Project, found that just 0.04% of international development aid — and 0.31% of grants by private foundations — targeted LGBTQ+ issues and beneficiaries globally.[10]“2017-2018 Global Resources Report: Government and Philanthropic Support for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Intersex Communities”. Global Philanthropy Project GPP and Funders for LGBTQ … Continue reading The funding shortfall was especially visible in the MENA region, where the report identified a mere $7.2 million allocated for LGBTQ+ donor support in the 2017-2018 period, the most recent period to have been studied. In the MENA region, this lack of funding has been attributed both to donors’ prioritisation of other issues, as well as a general perception that advancing such issues is too difficult in a region marked by explicit governmental and social hostility to LGBTQ+ populations. These conditions should not be seen as a stop sign preventing LGBTQ+ aid work, but they should prompt reflection. Activities targeting LGBTQ+ populations may require more effective mainstreaming and creative design and targeting criteria to avoid attracting unwanted attention from authorities, or potentially hostile elements of the broader community.

Authoritarian Context: LGBTQ+ Empowerment and Civil Society Space

Strict limitations on LGBTQ+ communities in Syria and the region are emblematic of a broader system of laws impeding civil society development. In this respect, empowering and expanding civil society itself is likely a necessary step in the empowerment of LGBTQ+ advocates. Donors seeking advancement on LGBTQ+ issues must therefore grapple with inter-related civil society objectives. Across the region, as in Syria, independent civil society organisations remain at risk of repression or co-optation, as powerbrokers insist on their monopoly not only over formal political power, but also of ideas (see: Function Over Form: Rethinking Civil Society in Government-held Syria).[11]“State of Civil Society Report 2016 – Executive Summary”. CIVICUS (2016): http://www.civicus.org/images/documents/SOCS2016/summaries/State-of-Civil-Society-Report-2016_Exec-Summary.pdf

For the foreseeable future, aid actors seeking to prioritise LGBTQ+ concerns will be forced to contend with the reality that, across the MENA region, the space for civil society to evolve and develop is deliberately constrained.[12]Schlumberger, O. (2006) “Dancing with wolves: Dilemmas of democracy promotion in authoritarian contexts”. In Jung, D. (ed.), Democratization and Development: New Political Strategies for the … Continue reading Authoritarian governance and the regrettably limited prospects for democratisation, heavy repression of online and offline civil society, and hostility towards LGBTQ+ populations socially and legally all contribute to making the region a difficult environment in which to advance such objectives. Optimism about civic change was buoyed by the so-called Arab Spring, during which Arab regimes faced crises of legitimacy brought about by economic malaise, diverse social demands, expectations of democratisation, and the shortcomings of liberalisation policies.[13]Albrecht, H., and Schlumberger, O. (2004) “Waiting for Godot: Regime change without democratization in the Middle East”. International Political Science Review, 25(4), 371–392. Ten years later, however, power still rests with many of the same regimes, and in many contexts, nominal democratic advances serve a “safety valve” function, while the public remains excluded from meaningful participation in government.[14]Barari, H. A. (2015) “The persistence of autocracy: Jordan, Morocco and the Gulf”. Middle East Critique, 24(1), 99–111. Nonetheless, despite the shortfalls of the ensuing political movements (and ostensibly pro-democracy armed uprisings), civil society space has expanded since 2011, with “more voices making their way into the public and political space, becoming more determined and assertive,” while more people “have been mobilized and are contributing to the conversation on change.”[15]ONTRAC. (2014) “Beyond Spring: Civil society’s role in the Middle East and North

Africa”. The Newsletter of INTRAC, 57, 1–8.

Programmatic Entry Points

Donors contemplating entry points and areas of programming for empowering and assisting LGBTQ+ Syrians will find valuable lessons learned across the region, based on an overview of existing aid work from comparable contexts. As noted above, however, programming in the Syrian context is particularly difficult given the absence of formal organisations with absorption capacity and the widespread governmental and social hostility to LGBTQ+ individuals. An animating principle in all such programming must, therefore, be the imperative to do no harm. Interventions must not put intended beneficiaries at risk, including by outing them, whether deliberately or unintentionally. It is also important that advocacy for LGBTQ+ rights not be seen as (and indeed, they should not be) an enterprise pushed by “the West.” Arguments that LGBTQ+ issues are a Western construct and are somehow incompatible with social mores in the Middle East are common, and they capitalise on broader anti-Western attitudes and existing sentiments towards LGBTQ+ individuals living in the region (see: Syria Update 14 December 2020).[16]Reference may be made to the case of Christian populations of the Middle East, who have in many contexts been exposed to greater social hostility as a result of perceived favouritism on the part of … Continue reading

Donor support for the LGBTQ+ community in Syria, and the broader MENA region, must therefore tread a fine line to avoid triggering pushback and inadvertently heightening the risks faced by LGBTQ+ persons. While the broad, overarching goal of legal rights and protections for LGBTQ+ individuals can be pursued through advocacy and the framework of human rights initiatives, it must be recognised that achieving these goals in Syria, as elsewhere, will take time.

Capacity building and support for local and regional organisations, measures to improve safety and protection, and a focus on health and sexual education and gender identity (SOGI) education are approaches that can be taken in the near term to aid LGBTQ+ Syrians. In the long term, a focus on advocacy and awareness will also be important. All such steps must, to the extent possible, be carried out in the spirit of localisation.

Awareness and Advocacy

Promoting the rights of LGBTQ+ Syrians is a long-term process that requires legal, social, and cultural change to tackle the hostility of wide segments of Syrian society towards LGBTQ+ individuals. Advocacy for and acknowledgement of the rights and needs of Syria’s LGBTQ+ population from the highest levels of the international development agencies and donors would do much to raise awareness, but may risk pushback from the Syrian Government. More targeted advocacy on issues particularly relevant to the LGBTQ+ community, such as confidential access to healthcare and an end to forced anal examinations for those suspected of “homosexual activity”, could be made through appeals less likely to receive pushback, such as under a general human rights framework or opposition to torture. Such advocacy through human rights frameworks has had some impact regionally. In 2014, Iraq accepted a United Nations recommendation to clamp down on discrimination, including on the grounds of sexual orientation,[17]“How homosexuality became a crime in the Middle East”. The Economist (2018):

https://www.economist.com/open-future/2018/06/06/how-homosexuality-became-a-crime-in-the-middle-east while Tunisia accepted a 2017 recommendation to end the use of forced anal examinations, although a formal ban has not been implemented on the practice, which continues with (often forced) “consent.”[18]Sierra C. Jackson, “Tunisia Vows to Ban Forced Exams of Suspected Gay Men”. NBC News (2017):

https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/tunisia-vows-ban-forced-exams-suspected-gay-men-n804616 Any such advocacy should be matched by awareness-raising activities throughout the aid and development sector, ensuring that practitioners are trained in LGBTQ+ sensitivity and are aware of the needs of and risks to this community.

Programmatic Approach: Media and Awareness

On the programmatic level, awareness-raising through media and culture is a way for LGBTQ+ individuals to share their stories and advocate for change on the social level. In general, LGBTQ+ individuals and issues are underrepresented in Arabic-language media, and when visible, they are usually depicted in a negative light and in pejorative terms.[19]Al-Abbas L. S. and Halder, A. S. (2020) “The representation of homosexuals in Arabic-language news outlets”. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal doi: … Continue reading In 2017 and with support from the Dutch embassy in Tunis, Association Shams established Shams Rad Radio, the first LGBT radio station in Tunisia and the Arab world, with the aim to build a community to discuss human rights, equality, and justice. In Lebanon, Qorras, supported by EU funding, has developed podcasts in which issues of sexuality and mental health are discussed. Platforms such as this have the dual purpose of both informing and educating the wider public and building a sense of community among LGBTQ+ people.

Influencing domestic Syrian media outlets, controlled by the Government, is not possible for the aid community. However, news outlets based outside the country have large audiences inside Syria and can be supported to provide more reporting on the issues facing the LGBTQ+ community. Many such platforms already receive donor support. Online platforms, although risking censorship, can provide an important space in which LGBTQ+ individuals can access information, share their stories, and connect with others — a necessary precondition for organising and developing civil society entities. Such steps are necessary to building eventual institutional capacity.

Capacity building

Developing the capacities of local and regional organisations that campaign for LGBTQ+ rights and provide opportunities and support for LGBTQ+ individuals is a key step, given the contextual knowledge of these actors and their ability to work directly on the ground. Capacity building can be carried out on both the individual and organisational level in regional countries, including those hosting the Syrian diaspora. Developing the capacity of employees and activists in this field will be important in ultimately enabling organisations to expand and professionalise, while facilitating networking and alliance building between organisations working across different human rights-related concerns. Crucially, such support can enable organisations to develop the ability to apply for and manage project funding from international donors, helping to establish them as more sustainable institutions.

Programmatic Approach: North-South Partnership

Drawing on the experience and expertise of established LGBTQ+ organisations in the Global North is an important means by which donor governments have facilitated support to organisations in the Global South. The Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA) and the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs have funded projects by the Swedish Federation for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer Rights (RFSL) and CoC Nederland, respectively, to provide capacity building and professional training to LGBTQ+ organisations in the Global South. The evaluation report conducted by SIDA found that RFSL’s projects contributed to strengthening networks and influence locally, regionally, and globally and that the majority of LGBTQ+ activists who participated had improved their leadership skills, resilience, and capacity to take action, influencing the practices of their organisations and improving their ability to strategise, fundraise, cooperate, and advocate for change. At the regional level, the Arab Foundation for Freedoms and Equality (AFE), based in Beirut, provides capacity building training, while the Euro-Mediterranean Foundation of Support to Human Rights Defenders (EMHRF)[20]“How do we work?” Euro-Mediterranean Foundation Of Support To Human Rights Defenders: https://emhrf.org/how-do-we-work/ offers organisational support grants.

However, as noted in our previous report, LGBTQ+ organisations are prohibited by law in Syria and other organisations that adopt or advocate for LGBTQ+ issues face the risk of forced dissolution (see: LGBTQ+ Syria: Experiences, Challenges, and Priorities for the Aid Sector). As a result, offering support to Syria-based organisations and individuals in this way could risk reprisals from Syrian authorities. Nevertheless, regional organisations or organisations based outside of Syria, such as those working with refugees or other diaspora communities, could be a crucial entry point for future work in Syria, should the legal situation change. Partnerships with regional organisations, which have networks in and knowledge of the region, can be used to channel funding to where it is needed.

Protection and safety

Given the risks of engaging in LGBTQ+ organising and activism in most contexts in the MENA region, there is a need for emergency protection activities for human rights defenders and their families. For example, the European Union Human Rights Defenders’ Mechanism[21]The European Union Human Rights Defenders Mechanism: https://protectdefenders.eu/ provides grants for the urgent protection of human rights defenders at risk in the MENA region through the Euro-Mediterranean Foundation of Support to Human Rights Defenders (EMHRF),[22]“How do we work?” Euro-Mediterranean Foundation Of Support To Human Rights Defenders: https://emhrf.org/how-do-we-work/ a regional foundation registered in Denmark since 2004. EMHRF has provided around €3 million in urgent grants to human rights defenders, to protect their lives and safety in dangerous contexts since 2005.

Programmatic Approach: Protection and Safe Spaces, On-Line and Off

Beyond protecting activists, however, there is also a need to provide safety and security for individual members of the LGBTQ+ community who may face persecution and discrimination while accessing basic necessities such as housing, healthcare, and employment. In Beirut, Helem has provided grants to LGBTQ+ individuals who need safe housing,[23]Maguie Hamzeh, “Queer and homeless: LGBTQ+ housing issues after the Beirut blast”. Beirut Today (2021):

https://beirut-today.com/2021/05/20/queer-and-homeless-lgbtq-housing-issues-beirut-blast/[24] Helem is the first LGBTQ+ rights non-governmental organisation in the Arab world, founded in Beirut, Lebanon, in 2001: https://www.helem.net/support and will open a specialised shelter for queer people facing homelessness in 2022. The Lebanese Medical Association for Sexual Health (LebMASH), founded by a group of healthcare professionals in 2012, developed LebGUIDE in 2017, a directory of clinicians from different specialities and areas in Lebanon that are LGBTQ+ friendly.[25]The Lebanese Medical Association for Sexual Health (LebMASH): https://lebmash.org/lebguide/ LebMASH was also awarded an emergency fund from MADRE to support the mapping of LGBTQ resources over Beirut, and is now creating a directory of LGBTQ+ friendly businesses and service providers.[26]The Lebanese Medical Association for Sexual Health (LebMASH), Annual Reports: https://lebmash.org/annual-reports-2/

Online and digital safety are also key considerations for LGBTQ+ individuals in Syria and the wider region as geolocation-based dating apps, such as Grindr, have been used to entrap, target, and arrest members of the LGBTQ community.[27]“Apps and traps: dating apps must do more to protect LGBTQ communities in Middle East and North Africa”. Article19 … Continue reading While there is little the international community can do to stop this practice, awareness raising of the risks of using such apps and training on digital safety and privacy is needed.

While urgent support for human rights defenders is needed in Syria, protection measures such as specialised shelters may be difficult to implement due to the need to coordinate with hostile local authorities. Nevertheless, there is a pressing need for such measures in neighbouring countries that host large numbers of Syrians, such as Turkey. Such projects could include mapping resources for LGBTQ+ Syrians, who may face a double hostility based on their nationality and sexual/gender identity in access to housing and healthcare.

Health and SOGI education

Under the umbrella of the response to HIV/AIDS, healthcare is a key entry point through which the LGBTQ+ community has been engaged and assisted in the MENA region, often focused on men who have sex with men (MSM), a key population targeted for prevention and treatment.[28]“Audacity in Adversity: LGBT Activism in the Middle East and North Africa”. Human Rights Watch (2018): … Continue reading More broadly, access to healthcare in a non-discriminatory setting is crucial, particularly for trans individuals (see: LGBTQ+ Syria: Experiences, Challenges, and Priorities for the Aid Sector). As healthcare is a key priority of donors and aid providers, it is crucial that practitioners are given adequate training and become aware of specific issues facing the LGBTQ+ community.

Programmatic Approach: Education Partnerships

Donor-supported education is another avenue for raising awareness of SOGI issues. For example, funded by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Masarouna is a five-year, multi-country programme and strategic partnership between the Arab Foundation for Freedoms and Equality (AFE),[29]Arab Foundation For Freedoms & Equality website: https://afemena.org/about/ RNW Media, and Oxfam Novib, to support young people to realise greater freedom and enjoy sexual and reproductive health and rights. The AFE is responsible for participatory grant-making (of between $5,000 and $20,000) and recently launched a call for proposals for community-led organisations in six Arab countries to propose projects concerning advocacy on sexual and reproductive health and rights for young people with various gender expressions.[30]Arab Foundation For Freedoms & Equality, Call for Proposals (2021): … Continue reading Masarouna is based on a two-pronged theory of change: capacity building for lobbying and advocacy, and strengthening civil society through thematic and technical capacity building. Health and education interventions in Syria should thus incorporate components concerning SOGI (to the extent possible), whether under the framework of human rights or sexual and reproductive rights.

Case Studies

Transnational Diffusion: The Role of Regional Cohesiveness and Foreign Aid

Scholars have long observed that policies, institutions, and human rights norms move across national borders. In the most simplistic and optimistic sense, this means that prosocial changes can spread,[31]Frank, D., B. Camp, and S. Boutcher. 2010. “Worldwide Trends in the Criminal Regulation of Sex, 1945 to

2005”. Advances in Science and Research 75 (6): 867–893. even if these processes are not always even or when change comes up against cultural norms concerning sexuality and gender.[32]Hughes, M., P. Paxton, S. Quinsaat, and N. Reith. 2018. “Does the Global North Still Dominate the International Women’s Movement?” Mobilization 23 (1): 1–21.[33] Symons, J., and D. Altman. 2015. “International Norm Polarization”. International Theory 7 (1): 61–95.[34] Hadler, M., and J. Symons. 2018. “World Society Divided”. SF Journal of Medicine and Research 96 (4):

1721–1756. This has myriad implications for donors contemplating LGBTQ+ focused aid interventions in Syria and elsewhere. On the most basic level, it suggests that donors can see a multiplier effect and greater overall impact if they engage in region-wide coordination, as the growth of civil society initiatives in one area can be harnessed to the benefit of LGBTQ+ organisations even in neighbouring contexts.

The case studies below highlight the progress and challenges for LGBTQ+ empowerment and advocacy in four contexts with similarities and key differences to Syria: Tunisia, Lebanon, Turkey, and Kosovo. All four have largely conservative, Muslim populations that are to some extent resistant to LGBTQ+ acceptance. While same-sex relations are legal in both Kosovo and Turkey, LGBTQ+ individuals face social stigma and hostility, with governmental efforts to combat discrimination either limited and patchy (Kosovo) or non-existent (Turkey). In Tunisia and Lebanon, same-sex relations remain illegal, though civil society organisations are campaigning for change and have achieved modest gains in securing registration (Tunisia) and outlawing the practice of forced anal testing (Lebanon). The implications for the Syria response are that progress is likely to be slow, given the constrained nature of civil society in the country and government hostility, and having measured, achievable objectives that take into consideration the social and political context and the specific challenges faced by the LGBTQ+ community is needed.

Tunisia

The space available for human rights and political freedoms in Tunisia has expanded considerably since the 2010-11 popular uprising and the ouster of President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali. In this context, LGBTQ+ advocates have achieved significant victories, including the first official registration for queer civil society organisations, yet campaigners continue to face threats, intimidation, smear campaigns, and legal harassment. Despite active campaigning to alter the nation’s penal code, however, “homosexual acts” and “sodomy” remain punishable by up to three years in prison, and approximately 100 Tunisians are convicted annually on the basis of this law.[35]PNUD, État des lieux des inégalités de genre et celles basées sur les orientations sexuelles en droit tunisien, 2021. According to information from the Ministry of Justice following a request … Continue reading LGBTQ+ people and women receive fewer legal protections generally,[36]“Tunisia, ten years on : After so much hope, the deception of women and LGBTQIs”. FRANCE 24 English (2021): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PYaBF6AyC4w and Tunisians with non-normative sexual orientations and gender identities have achieved few legal or social victories of note.[37]“Preliminary observations on the visit to Tunisia by the Independent expert on protection against violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity”. United Nations … Continue reading In 2017, President Beji Caid Essebsi established the Individual Freedoms and Equality Committee (COLIBE) to report on legislative reforms concerning individual freedoms and equality. While the final report called for the decriminalisation of homosexuality, opposition from the Ennahda party and the new president Kais Saied has meant that no progress has been made in implementing the recommendations.[38]Camille Lafrance, “Tunisie : les travaux sur les libertés individuelles de nouveau à l’ordre du jour ?” … Continue reading

A number of LGBTQ+ CSOs and NGOs, such as Damj,[39]Damj website (http://damj.org/) is down at the time of writing but their facebook page is active: (https://www.facebook.com/damj.tunisie/) Association Shams,[40]Association Shams Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/shamsassociation/ and Mawjoudin,[41]Mawjoudin Organisation website: https://www.mawjoudin.org/ have been founded and registered to support and advocate for sexual minorities. LGBTQ+ activists have also joined or partnered with other human rights organisations and promoted LGBTQ+ rights from within, such as Chouf, a feminist organisation that now works with women of all sexualities.[42]“Audacity in Adversity: LGBT Activism in the Middle East and North Africa”. Human Rights Watch (2018): … Continue reading In May 2015, Association Shams was the first organisation for LGBTQ+ rights to receive official authorisation from Tunisia’s interior ministry, but was forced to engage in a series of legal battles following the state’s attempts to shut it down.[43]“Tunisia’s Crackdown Against LGBT Rights Group”. The Newsmakers TRT World (2019):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LZDei-C6l0c The organisation and its members have been subjected to systematic smear campaigns by religious actors and conservative political groups in the country, a reflection of the risks to community acceptance for such organisations.[44]Front Line Defenders, SHAMS Organisation profile: https://www.frontlinedefenders.org/en/profile/shams In March 2020, Association Shams was granted legal protection in a ruling handed down by Tunisia’s Court of Cassation, which Bochra Belhaj Hmida, a former parliamentarian and chairperson of the Individual Freedoms and Equality Committee, described as a “legal and judicial revolution” in post-revolution Tunisia.[45]Amel al-Hilali, “LGBTQ association achieves major legal milestone in Tunisia”. Al-Monitor (2020): … Continue reading

Donor-funded aid projects have largely focused on providing assistance in healthcare and mental health, particularly for LGBTQ+ refugees through the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and its partners such as the Tunisian Refugee Council.[46]UNHCR Tunisia: Help for LGBTQ+ Refugees: https://help.unhcr.org/tunisia/services-in-tunisia/lgbtiq/ The provided services include assistance to navigate the healthcare system, counselling and mental health services, and support with social integration, life skills, and learning opportunities.

The case of Tunisia highlights the limitations of the potential opening of space for LGBTQ+ empowerment and advocacy during processes of democratisation in a context where social attitudes remain hostile. While the successful defense of Association Shams in the courts is a positive sign that civil society has some protections and can continue to work, the government’s refusal to implement the COLIBE recommendations and continued reports of violence against LGBTQ+ individuals and activists show that much work remains to be done. Implementing the recommendations of the COLIBE report and decriminalising homosexuality remain a focus of international advocacy and pressure.

Lebanon

Lebanon is regarded as one of the most liberal Arab countries with the greatest tolerance for LGBTQ+ identities. Nevertheless, Article 534 of the penal code prohibits “sexual intercourse against nature”, and it is an offense under Article 521 for a man to “disguise himself as a woman”. While there have been several cases of judges dismissing charges brought under Article 534 as not constituting “unnatural offenses”,[47]https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/lgbt_mena0418_web_0.pdf p2 the law remains on the books and continues to be used to target LGBTQ+ populations, particularly non-Lebanese persons living in the country.[48]“Lebanon LGBTI Resources”, Rights in Exile Programme: Refugee Legal Aid Information for Lawyers Representing Refugees Globally: https://www.refugeelegalaidinformation.org/lebanon-lgbti-resources In September 2015, a judge granted a trans man the right to change his legal status in the civil registry for the first time in Lebanon. Nevertheless, trans people in Lebanon are required to undergo gender reassignment surgery to legally change their gender, and must be unmarried and without children.[49]Joseph Mccormick, “Lebanon allows trans man to legally change his gender”. (2016): https://www.pinknews.co.uk/2016/01/28/lebanon-allows-trans-man-to-legally-change-his-gender/ The 2020 Beirut blast led to the destruction of many LGBTQ+-friendly spaces in the Mar Mikhayel, Gemmayze, and Geitawi neighbourhoods, the areas of Beirut most inclusive of diverse gender and sexual identities.[50]“Queer Community In Crisis: Trauma, Inequality & Vulnerability: Policy brief”. Oxfam (2020): … Continue reading

LGBTQ+ civil society organisations in Lebanon include Helem, which was founded in 2001 in Beirut and claims to be the oldest LGBTQ+ organisation in the Arab world. Through a campaign called “Tests of Shame” in 2012, Helem, along with other activists, was able to mobilise public opinion against the use of forced anal examinations against men arrested on homosexuality-related charges, leading to the Ministry of Justice issuing guidelines forbidding their use.[51]“Dignity Debased: Forced Anal Examinations in Homosexuality Prosecutions”. Human Rights Watch (2016): … Continue reading Nevertheless, use of these tests reportedly continues.[52]“Lebanon: Anal exams still being conducted on ‘suspected homosexuals’ despite ban”. PinkNews … Continue reading Helem operated two community and drop-in centres in Beirut to provide LGBTQ+ individuals with a safe space for free expression and community building, both of which were destroyed in the 2020 Beirut explosion.[53]Ban Barkawi, “Beirut blast destroys vital lifeline for LGBT+ Lebanese”. Reuters (2020): https://www.reuters.com/article/lebanon-lgbt-aid-idUSL8N2FD3LA and Fundraiser for Helem, Beirut-based … Continue reading

Donor support for LGBTQ+ issues in Lebanon are largely pursued through civil society and human rights frameworks, through funding for relevant CSOs as well as advocacy and engagement with political actors in the context of human rights and the decriminalisation of homosexuality.[54]Assem Dandashly, “The EU and LGBTI activism in the MENA – The case of Lebanon”. Mediterranean Politics (2021): https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13629395.2021.1883287 EU funding has also supported training and developing work-related skills for LGBTQ+ individuals and the creation of media campaigns focused on awareness, understanding, and empowerment.[55]“Does Your Therapist Know?”: https://podqast.qorras.com/index In the aftermath of the Beirut explosion and the destruction of spaces depended on by the LGBTQ+ community, there is a need to ensure that rehabilitation does not ignore the areas that have played a key role in the small but active space for LGBTQ+ civil society.

Kosovo

Although Kosovo is one of only ten European states to have constitutionally banned discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation, Kosovar society remains deeply traditional, and social hostility towards sexual minorities is pervasive. This contrast between progressive legal protection and conservative social attitudes is largely due to the involvement of the United States and European countries in advising Kosovo on the substance of its constitutional framework and pushing for its compliance with international human rights standards, thus the inclusion of the term “sexual orientation” in Article 24 of the 2008 Constitution pertaining to anti-discrimination.[56] Kosovo Constitution (2008): https://web.archive.org/web/20080526222929/http://www.kushtetutakosoves.info/?cid=2%2C250 There is a significant gap between legal protection on paper and implementation on the ground, however. Reports of discrimination against LGBTQ+ people are apparently seldom taken seriously by the police. To date, no discrimination case on the basis of sexual orientation has reached the courts.[57]Fauchier, Agathe. “Kosovo: What Does the Future Hold for LGBT People?” Forced Migration Review, no. 42, Refugee Studies Centre, University of Oxford, 2013, pp. 36–39. … Continue reading As a result, rising numbers of people from Kosovo are seeking asylum in other European countries on grounds of persecution for their sexual orientation.[58]Ibid. With reference to Syria, the situation in Kosovo is broadly analogous to that of the northeast, where the Autonomous Administration provides nominal guarantees for the rights of LGBTQ+ individuals that are not met in actual practice, in part due to the lack of social consensus.[59]“LGBTQ+ Syria: Experiences, Challenges, and Priorities for the Aid Sector”. Center for Operational Analyis and Research (COAR) (2021): … Continue reading

There are currently three active national LGBTQ+ organisations in Kosovo: the Centre for Equality and Liberty (CEL),[60]“What is the Centre for Equality and Liberty?” CEL website: https://cel-ks.org/en/about-us/ the Centre for Social Group Development (CSGD),[61]The Centre for Social Group Development (CSGD) website: https://csgd-ks.org/ and the Centre for Social Emancipation (QESH).[62]QESh website is down for maintenance at the time of writing. In May 2014, the EU funded a two-year project aimed at tackling homophobia by improving the relevant capacities of the “police, judiciary, educators and the media.”[63]“Finland Helps Kosovo Fight Against Homophobia and Transphobia”. National Institute for Health and Welfare (2014): https://www.refworld.org/docid/563c57544.html USAID has partnered with QESH on a project to conduct LGBTQ+ rights awareness and to monitor, report, and document cases of LGBTQ+ discrimination, conduct sensitivity training and liaise with relevant government officials to facilitate the creation of procedures and legal assistance for LGBTQ+ victims.[64]“Kosovo: Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2014”. United States (US) Department of State (2015): https://www.refworld.org/docid/563c57544.html

The strong protection of LGBTQ+ individuals by law in Kosovo that is nevertheless not matched in practice shows the need for advocacy and awareness to change social attitudes and reduce homophobia and transphobia. Were such a legal framework to exist in Syria, it would also likely face similar problems in implementation without a significant shift in attitudes from the security services and judiciary, as well as society more broadly.

Turkey

Homosexuality is legal in Turkey and LGBTQ+ legal rights are relatively advanced for the region, yet social and official opposition have grown in recent years amid legal and social challenges. Although sexual acts between same-sex partners above the age of 18 have never been a crime in Turkey, recent surveys have shown that the majority of respondents believe that homosexuality should be criminalised.[65]Volkan Yılmaz, “Lgbt Meselesinde Siyasi Tehditler Ve Olanaklar”. Bianet (2012): http://bianet.org/biamag/diger/139812-lgbt-meselesinde-siyasi-tehditler-ve-olanaklar No laws exist in Turkey to protect LGBTQ+ people from discrimination in employment, education, housing, healthcare, or public accommodation.[66]LGBTI Equal Rights Association for Western Balkans and Turkey – Turkey Profile: https://www.lgbti-era.org/content/turkey In addition, Turkey does not recognise same-sex marriages, civil unions, or domestic partnership benefits. Intolerance toward LGBTQ+ individuals manifests itself strikingly in hate murders and hate crimes. In 2010 alone, LGBTQ+ organisations in Turkey reported that 16 LGBTQ+ individuals were murdered because of their sexual orientation.[67]“Not an Illness nor a Crime’: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender People Demand Equality”. Amnesty International London (2011): https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/eur44/001/2011/en/ Many transgender women resort to sex work due to their exclusion from other forms of employment, and lesbian, gay, or bisexual individuals tend to hide their sexual orientation for fear of not being hired, losing their job, or not being promoted.

The main LGBTQ+ organisations in Turkey include the Kaos Gay and Lesbian Cultural Research and Solidarity Association (KAOS GL),[68]The Kaos Gay and Lesbian Cultural Research and Solidarity Association (KAOS GL) website: https://kaosgldernegi.org/en/ which was founded in 1994 in Ankara and was the first LGBTQ+ organisation to be officially registered in 2005, after legal battles with the Ankara Governorate. Its main efforts include advocating for and monitoring LGBTQ+ rights, including for refugees, and running the Kaos GL Magazine, and a Cultural Center. Another major organisation is the volunteer-run Lambdaistanbul LGBTI Solidarity Association,[69]Lambdaistanbul LGBTI Solidarity Association website: http://www.lambdaistanbul.org/s/lambdaistanbul-lgbti-solidarity-association/ which was started in 1993 as a cultural space for the LGBTQ+ community and was officially registered in 2006. Its main goal is a society free from all kinds of discrimination. Lambdaistanbul is a member of CSBR (Coalition of Sexual and Bodily Rights in Muslim Societies) and ILGA (International Lesbian and Gay Association). The Lesbian and Gay Inter-University Organization (LEGATO)[70]The Lesbian and Gay Inter-University Organization (LEGATO) web page: https://web.archive.org/web/20070224223947/http://www.unilegato.org/ was founded in 1996 and is Turkey’s largest LGBTQ+ organisation. LEGATO aims at bringing LGBTQ+ university students together and organises regular conferences and events.

The international community has been more engaged in LGBTQ+ issues in Turkey than in other countries in the MENA region, given the relative ease of operating in a country in which homosexuality is not criminalised and civil society organisations are able to exist openly, though not without some social hostility. Turkey’s history of EU candidacy also opened up further space for LGBTQ+ visibility in the public sphere. Nevertheless, there has been little progress in seeking added protections for the LGBTQ+ community in terms of discrimination and hate speech.[71]Zülfukar Çetin, “The Dynamics of the Queer Movement in Turkey before and during the Conservative AKP Government”. German Institute for International and Security Affairs (2016): … Continue reading

References[+]

| ↑1 | Ashley Currier, “Out in Africa”. University of Minnesota Press (2012): https://www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/out-in-africa |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | These include Armenia, Costa Rica, Mozambique, Nepal, and Nicaragua, among others. |

| ↑3 | India is among the countries to have re-criminalised homosexuality, while severe anti-LGBTQ+ laws have been introduced in Russia, Nigeria, and elsewhere. |

| ↑4 | Jacob Poushter and Nicholas Kent, “The Global Divide on Homosexuality Persists”. Pew Research Center (2020): https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2020/06/25/global-divide-on-homosexuality-persists/ |

| ↑5, ↑28, ↑42 | “Audacity in Adversity: LGBT Activism in the Middle East and North Africa”. Human Rights Watch (2018): https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/04/16/audacity-adversity/lgbt-activism-middle-east-and-north-africa |

| ↑6, ↑58 | Ibid. |

| ↑7 | “Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity SOGI”, Council of Europe: https://www.coe.int/en/web/sogi |

| ↑8 | “Avenues for Donors to Promote Sexuality and Gender Justice”. Institute of Development Studies (2016): https://rb.gy/y0ogc5 |

| ↑9 | Amy Lind, “Development, Sexual Rights and Global Governance”. Routledge (2010): https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/oa-edit/10.4324/9780203868348/development-sexual-rights-global-governance-amy-lind For instance, sexual health interventions are often limited to distributions of condoms and lubricant, irrespective of actual needs among target beneficiary populations. |

| ↑10 | “2017-2018 Global Resources Report: Government and Philanthropic Support for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Intersex Communities”. Global Philanthropy Project GPP and Funders for LGBTQ Issues (2020): https://globalresourcesreport.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/GRR_2017-2018_Color.pdf |

| ↑11 | “State of Civil Society Report 2016 – Executive Summary”. CIVICUS (2016): http://www.civicus.org/images/documents/SOCS2016/summaries/State-of-Civil-Society-Report-2016_Exec-Summary.pdf |

| ↑12 | Schlumberger, O. (2006) “Dancing with wolves: Dilemmas of democracy promotion in authoritarian contexts”. In Jung, D. (ed.), Democratization and Development: New Political Strategies for the Middle East. New York: Palgrave, pp. 33–60. |

| ↑13 | Albrecht, H., and Schlumberger, O. (2004) “Waiting for Godot: Regime change without democratization in the Middle East”. International Political Science Review, 25(4), 371–392. |

| ↑14 | Barari, H. A. (2015) “The persistence of autocracy: Jordan, Morocco and the Gulf”. Middle East Critique, 24(1), 99–111. |

| ↑15 | ONTRAC. (2014) “Beyond Spring: Civil society’s role in the Middle East and North Africa”. The Newsletter of INTRAC, 57, 1–8. |

| ↑16 | Reference may be made to the case of Christian populations of the Middle East, who have in many contexts been exposed to greater social hostility as a result of perceived favouritism on the part of Western donors, charities, and political leaders. |

| ↑17 | “How homosexuality became a crime in the Middle East”. The Economist (2018): https://www.economist.com/open-future/2018/06/06/how-homosexuality-became-a-crime-in-the-middle-east |

| ↑18 | Sierra C. Jackson, “Tunisia Vows to Ban Forced Exams of Suspected Gay Men”. NBC News (2017): https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/tunisia-vows-ban-forced-exams-suspected-gay-men-n804616 |

| ↑19 | Al-Abbas L. S. and Halder, A. S. (2020) “The representation of homosexuals in Arabic-language news outlets”. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal doi: 10.1108/EDI-05-2020-0130 |

| ↑20, ↑22 | “How do we work?” Euro-Mediterranean Foundation Of Support To Human Rights Defenders: https://emhrf.org/how-do-we-work/ |

| ↑21 | The European Union Human Rights Defenders Mechanism: https://protectdefenders.eu/ |

| ↑23 | Maguie Hamzeh, “Queer and homeless: LGBTQ+ housing issues after the Beirut blast”. Beirut Today (2021): https://beirut-today.com/2021/05/20/queer-and-homeless-lgbtq-housing-issues-beirut-blast/ |

| ↑24 | Helem is the first LGBTQ+ rights non-governmental organisation in the Arab world, founded in Beirut, Lebanon, in 2001: https://www.helem.net/support |

| ↑25 | The Lebanese Medical Association for Sexual Health (LebMASH): https://lebmash.org/lebguide/ |

| ↑26 | The Lebanese Medical Association for Sexual Health (LebMASH), Annual Reports: https://lebmash.org/annual-reports-2/ |

| ↑27 | “Apps and traps: dating apps must do more to protect LGBTQ communities in Middle East and North Africa”. Article19 (2018): https://www.article19.org/resources/apps-traps-dating-apps-must-protect-communities-middle-east-north-africa/ |

| ↑29 | Arab Foundation For Freedoms & Equality website: https://afemena.org/about/ |

| ↑30 | Arab Foundation For Freedoms & Equality, Call for Proposals (2021): https://afemena.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Call-for-proposal-Masarouna-Mobilizing-Young-Community-Based-Organizations-CBOs-to-lead-change-in-the-field-of-SRHR-across-MENA-Region.pdf |

| ↑31 | Frank, D., B. Camp, and S. Boutcher. 2010. “Worldwide Trends in the Criminal Regulation of Sex, 1945 to 2005”. Advances in Science and Research 75 (6): 867–893. |

| ↑32 | Hughes, M., P. Paxton, S. Quinsaat, and N. Reith. 2018. “Does the Global North Still Dominate the International Women’s Movement?” Mobilization 23 (1): 1–21. |

| ↑33 | Symons, J., and D. Altman. 2015. “International Norm Polarization”. International Theory 7 (1): 61–95. |

| ↑34 | Hadler, M., and J. Symons. 2018. “World Society Divided”. SF Journal of Medicine and Research 96 (4): 1721–1756. |

| ↑35 | PNUD, État des lieux des inégalités de genre et celles basées sur les orientations sexuelles en droit tunisien, 2021. According to information from the Ministry of Justice following a request made by the Twensa Kifkom project, there have been 1,917 people detained and convicted of homosexuality between 2008 and June 2020. |

| ↑36 | “Tunisia, ten years on : After so much hope, the deception of women and LGBTQIs”. FRANCE 24 English (2021): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PYaBF6AyC4w |

| ↑37 | “Preliminary observations on the visit to Tunisia by the Independent expert on protection against violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity”. United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner (2021): https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=27174&LangID=E |

| ↑38 | Camille Lafrance, “Tunisie : les travaux sur les libertés individuelles de nouveau à l’ordre du jour ?” (2020): https://www.jeuneafrique.com/mag/913546/politique/tunisie-les-travaux-sur-les-libertes-individuelles-de-nouveau-a-lordre-du-jour/ |

| ↑39 | Damj website (http://damj.org/) is down at the time of writing but their facebook page is active: (https://www.facebook.com/damj.tunisie/ |

| ↑40 | Association Shams Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/shamsassociation/ |

| ↑41 | Mawjoudin Organisation website: https://www.mawjoudin.org/ |

| ↑43 | “Tunisia’s Crackdown Against LGBT Rights Group”. The Newsmakers TRT World (2019): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LZDei-C6l0c |

| ↑44 | Front Line Defenders, SHAMS Organisation profile: https://www.frontlinedefenders.org/en/profile/shams |

| ↑45 | Amel al-Hilali, “LGBTQ association achieves major legal milestone in Tunisia”. Al-Monitor (2020): https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2020/03/tunisia-shams-association-gay-rights-legal-presence.html |

| ↑46 | UNHCR Tunisia: Help for LGBTQ+ Refugees: https://help.unhcr.org/tunisia/services-in-tunisia/lgbtiq/ |

| ↑47 | https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/lgbt_mena0418_web_0.pdf p2 |

| ↑48 | “Lebanon LGBTI Resources”, Rights in Exile Programme: Refugee Legal Aid Information for Lawyers Representing Refugees Globally: https://www.refugeelegalaidinformation.org/lebanon-lgbti-resources |

| ↑49 | Joseph Mccormick, “Lebanon allows trans man to legally change his gender”. (2016): https://www.pinknews.co.uk/2016/01/28/lebanon-allows-trans-man-to-legally-change-his-gender/ |

| ↑50 | “Queer Community In Crisis: Trauma, Inequality & Vulnerability: Policy brief”. Oxfam (2020): https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Policy%20Brief%20-%20Queer%20Community%20in%20Crisis%20June%202021%20.pdf |

| ↑51 | “Dignity Debased: Forced Anal Examinations in Homosexuality Prosecutions”. Human Rights Watch (2016): https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/07/12/dignity-debased/forced-anal-examinations-homosexuality-prosecutions |

| ↑52 | “Lebanon: Anal exams still being conducted on ‘suspected homosexuals’ despite ban”. PinkNews (2014): https://www.pinknews.co.uk/2014/07/16/lebanon-anal-exams-still-being-conducted-on-suspected-homosexuals-despite-ban/ |

| ↑53 | Ban Barkawi, “Beirut blast destroys vital lifeline for LGBT+ Lebanese”. Reuters (2020): https://www.reuters.com/article/lebanon-lgbt-aid-idUSL8N2FD3LA and Fundraiser for Helem, Beirut-based LGBTIQ Organization https://outrightinternational.org/content/fundraiser-helem-beirut-based-lgbtiq-organization |

| ↑54 | Assem Dandashly, “The EU and LGBTI activism in the MENA – The case of Lebanon”. Mediterranean Politics (2021): https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13629395.2021.1883287 |

| ↑55 | “Does Your Therapist Know?”: https://podqast.qorras.com/index |

| ↑56 | Kosovo Constitution (2008): https://web.archive.org/web/20080526222929/http://www.kushtetutakosoves.info/?cid=2%2C250 |

| ↑57 | Fauchier, Agathe. “Kosovo: What Does the Future Hold for LGBT People?” Forced Migration Review, no. 42, Refugee Studies Centre, University of Oxford, 2013, pp. 36–39. https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:b1dd37ff-cc13-4fb5-8a5d-deb4151e19ec |

| ↑59 | “LGBTQ+ Syria: Experiences, Challenges, and Priorities for the Aid Sector”. Center for Operational Analyis and Research (COAR) (2021): https://www.coar-global.org/2021/06/22/lgbtq-syria-experiences-challenges-and-priorities-for-the-aid-sector/ |

| ↑60 | “What is the Centre for Equality and Liberty?” CEL website: https://cel-ks.org/en/about-us/ |

| ↑61 | The Centre for Social Group Development (CSGD) website: https://csgd-ks.org/ |

| ↑62 | QESh website is down for maintenance at the time of writing. |

| ↑63 | “Finland Helps Kosovo Fight Against Homophobia and Transphobia”. National Institute for Health and Welfare (2014): https://www.refworld.org/docid/563c57544.html |

| ↑64 | “Kosovo: Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2014”. United States (US) Department of State (2015): https://www.refworld.org/docid/563c57544.html |

| ↑65 | Volkan Yılmaz, “Lgbt Meselesinde Siyasi Tehditler Ve Olanaklar”. Bianet (2012): http://bianet.org/biamag/diger/139812-lgbt-meselesinde-siyasi-tehditler-ve-olanaklar |

| ↑66 | LGBTI Equal Rights Association for Western Balkans and Turkey – Turkey Profile: https://www.lgbti-era.org/content/turkey |

| ↑67 | “Not an Illness nor a Crime’: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender People Demand Equality”. Amnesty International London (2011): https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/eur44/001/2011/en/ |

| ↑68 | The Kaos Gay and Lesbian Cultural Research and Solidarity Association (KAOS GL) website: https://kaosgldernegi.org/en/ |

| ↑69 | Lambdaistanbul LGBTI Solidarity Association website: http://www.lambdaistanbul.org/s/lambdaistanbul-lgbti-solidarity-association/ |

| ↑70 | The Lesbian and Gay Inter-University Organization (LEGATO) web page: https://web.archive.org/web/20070224223947/http://www.unilegato.org/ |

| ↑71 | Zülfukar Çetin, “The Dynamics of the Queer Movement in Turkey before and during the Conservative AKP Government”. German Institute for International and Security Affairs (2016): https://www.swp-berlin.org/publications/products/arbeitspapiere/WP_RG_Europe_2016_01.pdf |