Conflict Analysis – Lebanon – National Level

Background

Ever since Lebanon emerged as an independent state, its history has been marked by sectarian strife, political divides, and unstable relations with neighbouring countries — all of which have driven the country into conflict at different points in time. While many of these issues remain unresolved (and continue to be critical drivers of conflict), recent events in Lebanon have reshaped these long-term social fissures and created new ones. Lebanon is now facing the worst economic crisis in its modern history — a crisis that the World Bank has ranked as within the world’s top 3 most severe economic crises since the mid-19th century.[1]“Lebanon Sinking into One of the Most Severe Global Crises Episodes, amidst Deliberate Inaction,” World Bank, 1 June 2021. Available at: … Continue reading The deteriorating economic situation has prompted a spike in unemployment and food insecurity; according to UN ESCWA, 82 percent of households in Lebanon live in multidimensional poverty whereas 40 percent are classified as suffering from extreme multidimensional poverty.[2]“Multidimensional poverty in Lebanon (2019-2021)”, UNESCWA, September 2021. Available at: … Continue reading The COVID-19 pandemic has placed additional strain on the country’s economy and health system. Meanwhile, the 4 August 2020 explosion at Beirut Port damaged and destroyed hundreds of homes and fuelled popular anger. The country has repeatedly suffered from extended governance vacuums and, despite the recent government formation, remains dominated by a clientelist system that is increasingly unable to provide even the basic functions of governance, let alone implement much needed reforms.

These contextual developments have created new types of intra-Lebanese social tensions. Armed clashes over fuel, food, water, and other basic resources have become the new normal, and will likely only increase in the coming months and years. The failure of the state to provide even the most basic services, such as electricity and health, and items, both food and NFIs (non-food items), is fuelling popular anger, driving protests and violent riots across the country and causing dozens of injuries. Crime rates have spiked, with the incidence of some crimes (such as murder) increasing by almost 90 percent in the past year.[3]See: “Robberies, murders, suicides, and road accidents (2019-2020),” The Monthly, 1 March 2021. Available at: … Continue reading Xenophobia against refugees, Syrians in particular, has grown more intense as the Lebanese population become increasingly protective of the limited resources in the country. Meanwhile, the hollowing out of the state’s security apparatuses has triggered a rise in the phenomena of community policing; in areas like Tripoli and Akkar, children as young as 15 are seen carrying weapons on the basis that they are protecting the community. Finally, given that the roots of historic conflicts have been left unaddressed, civil war grievances are resurfacing and tolerance towards “the other” is decreasing. Protests and other acts of popular anger are increasingly taking on sectarian overtones as people retreat to their confessional identity.[4]“Lebanon: Assessing Political Paralysis, Economic Crisis and Challenges for U.S. Policy,” United States Institute of Peace, 29 July 2021. Available at: … Continue reading It is becoming increasingly clear that Lebanon is entering a new era, one likely dominated by increased conflict conditions across the country. These emergent dynamics necessitate an understanding of how the coming conflict in Lebanon may take shape, which areas will be most affected, and how the most vulnerable groups, including children and women, will be impacted.

This scenario will analyse the conflict in Lebanon at the national level, by examining conflict causes (structural and proximate), involved actors, and current conflict dynamics. Three scenarios, ranked from most to least likely, will then be given to analyse how conflict is likely to unravel in the near to medium term, with a focus on the capital, Beirut. Of note, this scenario plan is predicated on a one-to-two-year time frame.

Drivers of Conflict in Lebanon

Structural Drivers

-

Confessional Political System

Underlying Lebanon’s current crises lies the formalised sectarian confessional governing structure. With a system rooted in the Ottoman and colonial history of the country, Lebanon’s consociational democracy distributes executive positions, as well as many other powers and institutions, through a system of confessional power-sharing that is governed by political leaders representing different religious or ethnic communities. This confessional system existed as a largely informal communal power sharing agreement prior to the Lebanese Civil War; the postwar Ta’if Accord formalized this system in 1989, essentially institutionalizing the wartime militias into the political system and distributing political power and institutional responsibilities among the different sectarian groups in Lebanon. While the intention was to incentivise power sharing and inter-sectarian buy-in, the system has — in practice — also led to near-constant political gridlock and the entrenchment of sectarian patronage practices in state institutions, leaving successive Lebanese governments largely unable to perform core functions. Indeed, because Lebanon’s confessional government system has effectively codified sectarian identity into Lebanese political institutions, governance disputes necessarily become sectarian issues. Similarly, this system also essentially requires sectarian political leaders to prioritize securing resources for their own community (at the expense of others), which results in a hollowing out of state service provision in favour of corrupt patronage networks.

-

Syrian-Lebanese Relations

Lebanon’s relationship with Syria is a defining element of its political landscape. Divided opinion over whether Lebanon should be an independent state or a part of “Greater Syria” was a major driver of the civil war. The Syrian army was a major participant in the war and continued to occupy Lebanon until 2005, when they were ousted during the Cedar Revolution. The onset of Syria’s civil war in 2011 — and the resulting influx of Syrian refugees to Lebanon — has been a major source of political and social tension. Different groups within the country hold differing opinions regarding Lebanon’s orientation to the Al-Assad government, the Syrian opposition, Islamist groups, and the Syrian refugee community.

As of November 2020, the government of Lebanon estimates that the country hosts 1.5 million Syrians who have fled conflict.[5] “Lebanon Crisis Response Plan 2017-2021 (2021 Update),” United Nations and the Government of Lebanon. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/LCRP_2021FINAL_v1.pdf

Especially in the current climate, many Lebanese consider refugees to be a further strain on an already fragile economy, weak infrastructure, and limited services; they also accuse them of taking employment opportunities and undercutting Lebanese workers. Hezbollah’s interference in the Syrian war deepened divisions between Lebanese with different stances toward the Assad government. It also partially led to the Syrian conflict spilling into Lebanon, further exacerbating long-standing political-sectarian tensions. Examples include the bombing campaigns targeting Shiite neighbourhoods in 2013-2015, and clashes between Alawite and Sunni communities in Tripoli’s neighbourhoods of Jabal Mohsen and Bab Al Tabbaneh, which have killed more than 200 people and injured more than 2,000 in the past eight years.[6] “North & Akkar Governorates Profile,” OCHA, October 2018. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/North-Akkar_G-Profile_181008.pdf

The economic crisis and increasingly dire living situation have further exacerbated these Syrian-Lebanese tensions, as Lebanese grow more protective of the dwindling resources available. For example, recent hostile acts against Syrians took place in May 2021, when Lebanese assaulted Syrians who were on their way to cast votes at the embassy in Baabda.

-

Lebanese-Israeli-Palestinian Relations

Lebanon’s relationships with its Palestinian refugee community and with Israel are critically important drivers of the country’s political trajectories. Since 1948, numerous waves of Palestinian refugees have been displaced into Lebanon. According to recent figures, there are 257,000 Palestine refugees residing in the country.[7] “Lebanon Crisis Response Plan 2017 – 2021 (2021 Update).” Available at: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/LCRP_2021FINAL_v1.pdf

The Palestinian-Israeli conflict spilled into Lebanon in the 1970s and is a considered among the key factors that sparked the country’s civil war. Fierce armed clashes took place between Palestinian and Lebanese armed groups resulting in several massacres on both sides. The current economic crisis and increasingly dire living situation is further exacerbating tensions between Palestinian refugee communities and the Lebanese, as the latter are growing more protective of the country’s remaining resources. Of note, Palestinian refugees in Lebanon are marginalised and lack citizenship, with minimal access to work, civil status, and land ownership rights.

Lebanon and Israel remain formally at war, and relations between the two countries have been extremely tense for almost 50 years. In 1982, during the Lebanese Civil War, Israel invaded parts of Lebanon under the claim of driving out Palestinian fighters. Despite its withdrawal from most of the country, Israel continued to occupy southern Lebanon until May 2000. Arguably, since then, tensions have been mounting between Israel and Hezbollah, rather than between Israel and the Lebanese state. These tensions resulted in the 2006 war, which saw heavy damages to Beirut’s southern suburbs. Since then, despite skirmishes and ad hoc upticks in tension — such as the recent spill over from the Hamas-Israel armed confrontation — an open armed conflict between Lebanon (or Hezbollah) and Israel remains unlikely in the near to medium term.

Proximate Drivers

-

Poor Governance and Corruption

Decades of malpractice, misuse of public funds, and widespread institutional corruption have led to the collapse of the banking sector and, subsequently, Lebanon’s whole economy. Since the end of the civil war, the country has been governed by many civil war–era leaders, who have plundered public funds and used them to both enrich themselves and feed complex patronage networks (primarily by issuing state contracts to their inner circles, or by granting public sector jobs to their supporters). Much of this public-sector looting was essentially funded by the Lebanese banking sector (itself closely linked to the political elite). Compounded debt and diminishing central bank reserves have led to severe hyperinflation. To date, the Lebanese pound has lost more than 90 percent of its value and overall inflation has exceeded 84 percent. Banks have been imposing informal capital control measures, which have effectively denied depositors access to their deposits and severely restricted their withdrawals. International transfers, including tuition and living fees of students studying abroad, have been halted. These restrictions have triggered country-wide protests, roadblocks, and riots against the government and the banks. Many of these protests have turned violent, with people vandalising banks, preventing bank employees from entering their workplaces, holding bank employees hostage, and even assaulting them.[8]For some examples of the vandalisation of banks, see: “Angry Protesters Vandalize Banks in Lebanon,” The Daily Star, 28 April 2020. Available here: … Continue reading

-

Economic Crisis and Lack of Service Provision

Partially as a function of state corruption, the banking sector collapse, and hyperinflation, Lebanon is now facing a severe economic crisis rooted in a wider import crisis. Food prices have soared by up to 400 percent as of the end of December 2020.[9]Dana Khraiche and Ainhoa Goyeneche, “Lebanese Inflation Hits Record High as Food Prices Soar 400%,” Bloomberg, 12 February 2021. Available here: … Continue reading Similarly, the price of fuel has increased by more than 40 percent in the formal market. Hoarding and monopolizing of fuel, food, medicines and other basic subsidized items has caused the thriving of a black market to which residents are now obliged to resort to, paying up to LBP 500,000 for a 10-litre gallon of gasoline. This has triggered clashes, mostly armed, among customers at fuel stations, supermarkets, and pharmacies, and between customers and employees or owners, causing injuries and fatalities. In one incident in particular, at a fuel station in Deir ez Zahrani, armed clashes left 12 people injured.[10] See: “Clashes Over Car Refuelling Results in 12 Injuries in Ez Zahrani,” Lebanon 24, 30 June 2021. Available here: https://www.lebanon24.com/news/lebanon/838447/12

Moreover, the lack of fuel and fuel imports has led to decreased provision of services in general (especially electricity and water), which has also fuelled popular anger and frustration. This has, on several occasions, turned violent. The economic crisis and deteriorating service provision is a new type of tension that is fuelling popular anger, both against the state and among the Lebanese population, as they compete over limited resources. Given the entrenched sectarian schisms in the country, clashes have taken on — and are increasingly expected to take on — a sectarian undertone.

-

Unequal Distribution of Resources and Uneven Development Efforts

Lebanon suffers from severe social inequality, unequal distribution of resources, and uneven developmental efforts. Regional disparities are evident in several basic development indicators such as provision of public services (roads, water networks, electricity, etc.), human development levels (literacy and education) and social structure and living conditions.[11] “Poverty and Wealth Disparities,” Social Watch. Available at: https://www.socialwatch.org/node/10767

While not applicable to whole districts or areas, the central governorates of Beirut and Mount Lebanon have benefitted from developmental efforts; on the opposite side of the spectrum, other governorates, such as the South, North, and Akkar, have been systematically marginalized and neglected by the state. Prior to the current crisis, electricity cuts in Beirut were restricted to three hours per day; however, they regularly exceeded 10 hours in other governorates. It is not surprising that Tripoli, long one of the most impoverished districts in the country, has witnessed the most intense violence of any region since the uprising of October 2019. This uneven development is compounded by a regressive and dysfunctional tax collection system which leads to even further inequality, with many parts of the country lacking critical governance funding. Tensions between communities have also been rising because of inequality and uneven resource distribution and developmental efforts. For example, in Tripoli, Deir Amar, and Akkar, residents have been obstructing the road in front of trucks carrying fuel to other areas of Lebanon; they have then confiscated the fuel and distributed it in their region — on the basis that they are more deprived and hence more worthy of the resource. In Akkar in particular, this has caused critical tensions between areas such as Wadi Khaled and Bire Akkar. Tensions between areas will only continue to grow as the crisis continues.

-

Hollowed-out Security Services

The economic crisis has affected Lebanon’s security apparatus. Last year, due to funding challenges, the army removed meat from meals provided to soldiers on duty. The devaluation of the currency has eroded the value of soldiers’ salaries, due to an almost 90 percent decrease in the army’s payroll budget.[12] Michael Young, “A Military Lifeline,” Carnegie Middle East Center, 16 June 2021. Available here: https://carnegie-mec.org/diwan/84756

According to various media reports, the devaluation of salaries has triggered an increase in the number of soldiers requesting furlough, and the number of senior commanders seeking early retirement.[13]oseph Habouch, “Deteriorating Lebanon concerns U.S. officials after army warns of ‘social explosion’,”

Al Arabiya, 8 March 2021. Available here: … Continue reading Budgetary constraints have also prompted the military to make searing cuts to even the most basic employment benefits.[14] “Army holds on to neutrality as chaos spreads across Lebanon,” The Arab Weekly, 10 March 2021. Available here: https://thearabweekly.com/army-holds-neutrality-chaos-spreads-across-lebanon

Internal security services face similar challenges. The implications of this new reality have been evident on the ground. Crime rates have seen a critical surge, whereby instances of murder in December 2020 showed a year-over-year increase of 91 percent, while theft increased by 65 percent.[15]See: “Robberies, murders, suicides, and road accidents (2019-2020),” The Monthly, 1 March 2021. Available at: … Continue reading In turn, rising crime levels have provoked increasing vigilantism and impromptu community policing, indicating an erosion of trust in security services. This phenomenon has particularly been seen in the North and Akkar governorates, where crime levels, armed clashes, and other community insecurity events are on the rise. Indeed, community “policing” — or the development of local militias — is now becoming the norm in many parts of the country.

Stakeholders

Following is a brief and circumscribed list of actors who are involved in Lebanon’s wider conflict dynamics and who have the capacity to either escalate or deescalate conflict tensions. The list is not exhaustive and only includes actors with critical or major roles in Lebanon’s conflict dynamics.

| Type | Name / Role | Impact on Programme | Recommendations |

| Traditional political parties (and their associated armed wings) | Free Patriotic Movement (FPM) | Potential Spoilers:

|

|

| Amal Movement | |||

| Hezbollah | |||

| Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP) | |||

| Future Party | |||

| Lebanese Forces (LF) | |||

| Kataeb | |||

| Marada Movement | |||

| Progressive Socialist Party (PSP) | |||

| Arab Unification Party (AUP) | |||

| Lebanese Democratic Party (LDP) | |||

| Organised political activist groups | Examples include:

Mouwatinoun wa Mouwatinat fi Dawla, Lihaqqi, Marsad, Beirut Madinati |

Potential Stabilizers:

|

|

| Area-based groups | Examples include:

Kantari group, Chevrolet group, Jal el Dib group, and Verdun group |

||

| Security actors | Internal Security Forces | Potential Stabilizers:

Potential Spoilers:

|

|

| Lebanese Armed Forces | |||

| Community Police/Local Militia/Vigilante Groups | Potential Stabilizers only in early stages: filling the vacuum of security services

Potential Spoilers: in later stages as they increasingly resemble vigilante and militia groups; possible harassment of certain groups (of different sects or nationalities) |

|

|

| Municipalities | Generally, the role of municipalities in Lebanon is limited, as they are often constrained administratively and financially. However, this is highly locally dependent: some are highly developed and effective, and are critical service providers. Their capabilities and role are thus heavily area dependent. | Potential Stabilizers:

Potential Spoilers:

|

Engagement, information sharing, project design, coordination for implementation

Risk:

|

Despite the differences in the three constructed scenarios outlined below, these actors are expected to play critical roles in all of them:

Traditional political parties: Parties can loosely be categorised into two groups: those supporting the current government (FPM, Amal Movement, Hezbollah, Marada, SSNP, AUP, and LDP) and those opposing the current government (Future Party, LF, Kataeb, PSP). These are not defined camps; some of these parties, like Marada, support Hezbollah and the resistance block but have a tense relationship to FPM, and others like PSP change allegiances regularly. Parties supporting the government have been vocal in their rejection of demonstrations, whereas parties opposing the current government have claimed to support demonstrators. These claims are mostly seen as opportunistic attempts to capitalise on the protests for political gains. Generally, most of these traditional political parties are primarily interested in sustaining their positions in power, and distributing economic resources to their supporters. As such, these parties are expected to play two main roles in conflict dynamics. Firstly, they will resist any sweeping victory for the uprising and the independents in the upcoming parliamentary elections. Secondly, these parties will continue to fuel sectarian strife and back their supporters in localised armed clashes and skirmishes.

Organised political groups: These structured groups of activists each have their own mission and agenda. Some have participated in previous rounds of municipal and parliamentary elections, while others are entirely new. These groups will play a critical role in the upcoming parliamentary elections, as they will fiercely compete with the traditional political parties for parliamentary seats.

Area-based groups: These are groups formed of civilian networks in certain geographical areas and are mainly involved in street action, like protests, roadblocks, and riots. Such groups are expected to expand and to escalate violence in the streets; many will also likely back organised political groups in the next elections.

Security institutions: The role of Lebanon’s different security forces remains a major unknown. Thus far, security forces have generally been heavy handed when confronting protesters, though a majority of the population still favour the LAF over other security apparatuses. However, continued funding issues and internal fractures remain a distinct possibility. Moreover, the development of new highly local community police and de facto militias is a new and concerning development — one that may fuel and intensify conflict between different communities as the crisis continues.

Scenarios

1- No War, Many Conflicts

Pessimistic – Most Likely

This scenario assumes that Lebanon’s economic, social, political, and security situation will further deteriorate and devolve into escalated, albeit localised, violence. In this scenario the country continues on its current trajectory of economic collapse, with a total lifting of subsidies causing prices to spike; this will also cause even more severe shortages of basic items, including food, fuel, and medicine. People already struggling to make ends meet will fall into poverty and those already poor will plunge from food insecurity to full starvation. State services such as electricity, water, and waste management will be reduced to the bare minimum; many parts of the country outside of major cities will have no state services provided whatsoever. Health services will be critically impacted by the absence of electricity and shortage of medical supplies; medical staff shortages will also be an issue, as Lebanon’s professionals increasingly seek work opportunities abroad. Politically, while a new government was formed, it is unlikely that it will maintain a significant degree of support from the wider population, which has largely lost all trust in traditional political elites. Moreover, due to the lack of consensus and the implications on the businesses of the political elites, the government will most likely fail to produce an economic reform package and subsequently is unable to access international loans and funds. This scenario assumes that the upcoming parliamentary elections will not take place, resulting either in a state of political paralysis or an extension of the current parliament’s term, as happened in 2014. Either scenario would be like pouring gasoline on a fire, fuelling popular anger that is already at boiling point given the deteriorating economic, social, and service provision situation. Security apparatuses, mainly ISF and LAF, will struggle to maintain security, especially outside urban areas. This will lead to surging violence throughout the country as localised violence becomes the norm in the absence of effective security forces. While no national-level civil war ever fully takes place, numerous local level conflicts become the de facto reality in much of the country, as different communities and actors compete over resources and local rivalries.

Triggers

| Economic | Total lift of subsidies on all basic items |

| Extreme shortages of all basic items | |

| A surge in prices of all basic items to align with the black-market exchange rate | |

| Black-market rate climbs to over 40,000 LBP/USD | |

| Food insecurity becomes a major concern | |

| A severe housing crisis in the medium term as renters are unable to pay rent | |

| A large spike in unemployment due to wider business failure | |

| Services | Electricity becomes nearly absent, while fuel is expensive and in short supply — severely impacting daily life and transportation |

| Access to safe and clean water becomes an issue, as the government has reduced capacity to pump water to houses; water trucking becomes less affordable as fuel prices push up water prices | |

| Health services are severely impacted due to shortages of fuel, medicine, medical equipment, and staff; hospitals able to operate will increase their prices to a level only a minority can afford; the NSSF is barely functional; access to medicine is an issue due to shortages and increased prices (that will likely align with the black-market rate) | |

| Political | Government formed doesn’t satisfy the population |

| Government fails to produce an economic reform package and can’t access international loans and funds | |

| Upcoming parliamentary elections don’t take place; political paralysis, or extension of the current parliament’s term | |

| Assassinations of prominent political figures | |

| Security | Worsening treatment of protesters, leading to more injuries and fatalities |

| Local armed groups proliferate, mainly for communal self-defence (the majority likely have ties to political parties) | |

| Increased risk of proliferation of extremist groups, especially in Tripoli, Saida, and Palestinian camps | |

| Increased crime rate and communal violence |

Indicators:

- Increased formation and proliferation of armed groups

- Increased frequency and intensity of armed clashes

- Multiple incidents of armed clashes start taking place at the same time in different localities

- Armed clashes take place for prolonged hours and become more difficult to contain

- Political groups rearm their militias/armed wings

- Political and economic triggered chaos returns more heavily to the streets with a rise in violence and riots

Conflict Dynamics –

The dire economic situation, increased crime rate and hollowing out of security services will trigger localised armed confrontations throughout the country. This is different from a full-scale civil war in that it does not strictly involve political armed militias and is not strictly aimed at long-term political gains, but it is also more severe than the current spontaneous armed clashes. The human impact, however, largely resembles that of an open civil war in terms of physical and psychosocial safety and wellbeing, hindrance of movement and specific effects on the most vulnerable groups such as children and females. This scenario presumes that community armed groups will form in different localities, mainly for communal protection, to counter the state’s inability to provide security. These forms of communal policing are expected to become more organised and to gain prominence in their respective localities. However, the formation of militias that are far more organised and have direct ties to political parties is also possible and, arguably, is already taking place in many parts of Lebanon.[16] “Lebanon Scenario Plan,” COAR, July 2021. Available at: https://www.coar-global.org/lebanon-2/

Communal armed groups were already seen in the North in late June, when large groups of armed individuals took to the streets in Tabbaneh, Qoubbe, Tal, Jessrine, El Beddaoui, Mankoubin, and Abou Samra, shooting in the air and forcing shops to close. The LAF eventually entered Tripoli to control the volatile atmosphere but were forced to briefly pull out of some areas, such as Tabbaneh, to avoid armed confrontations with angry residents. The heightened atmosphere prompted Tripoli’s mayor to state that “the situation has spiralled out of control”. Moreover, areas such as Tripoli and Saida are hotbeds for extremism — the risk of which is critically heightened as groups can recruit individuals for as low as 50-100 USD per month. Increasingly, given Lebanon’s sectarian structure, armed confrontations are expected to take on a sectarian form. This was most recently evident in Tayyouneh, where heavy armed clashes took place between supporters of Lebanese Forces and supporters of Hezbollah/Amal parties during a protest organized by Hezbollah to denounce what they described as the “politicisation” of the investigation into the Beirut port explosion. While details of how events escalated are still disputed, clashes resulted in seven fatalities and more than 30 injuries, the highest number of recalled casualties due to an inter-sectarian clash in years. Moreover, the incident showcased that heavy arms, training and armed mobilization is not confined to Hezbollah anymore. As the state is increasingly incapable of providing the most basic items and services, the population will be forced to turn back to traditional elites. Of course, spontaneous clashes will continue to take place over resources at fuel stations, supermarkets, and pharmacies, with increased frequency and intensity. Inter-clan and -familial violence will likely also increase, especially as localities become increasingly charged with competing political and economic actors.[17]Ibid.

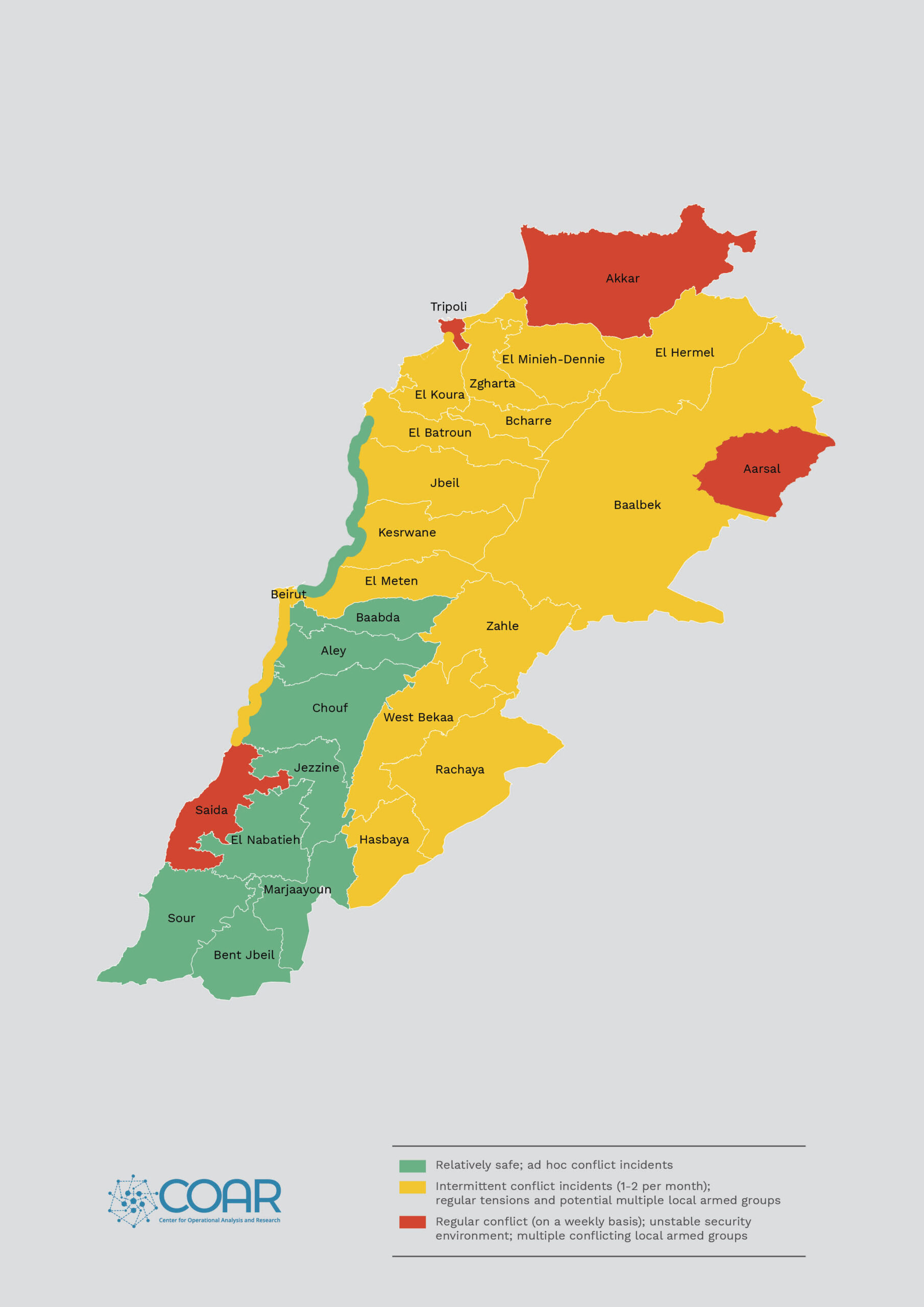

The map below shows hotspot areas on the national level, where communal armed groups are most likely to form or where clashes are most likely to take place. The colour codes, and consequent categorization of areas, are based on both historical events and grievances which remain unaddressed and unresolved, as well as on current events and incidents that have taken place since October 2019.

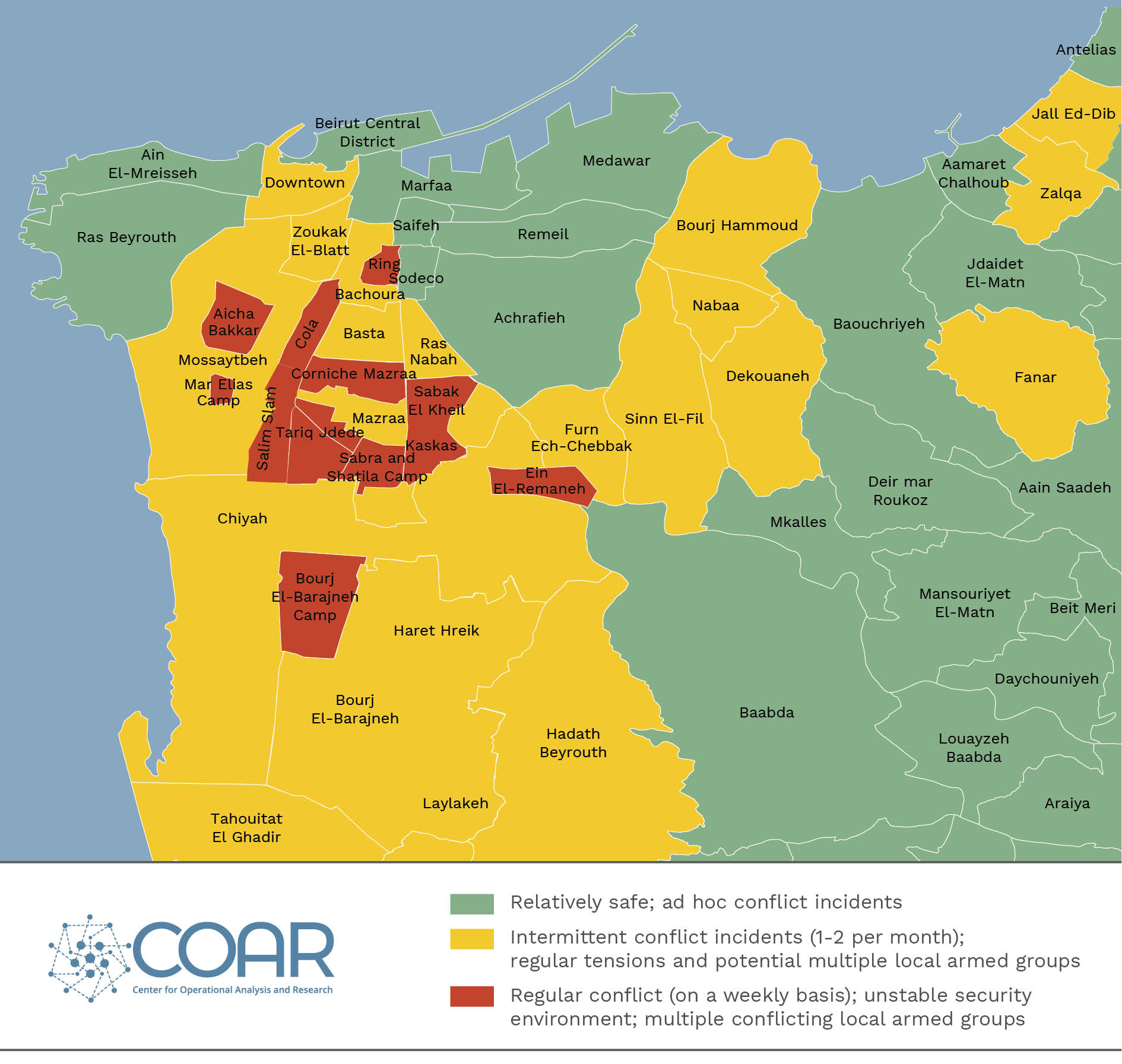

The below map focuses on Beirut city and shows hotspot areas where communal armed groups are most likely to form or where clashes are most likely to take place:

As shown on the map, hotspot areas in Beirut largely align with those that emerged during the civil war. While the formation of armed groups will initially be for the purpose of communal protection, they will increasingly take on sectarian undertones — for instance, dividing Shiites and Christians in Ain er Roummane-Chiayah or Khandak Al Ghameek-Ring areas, and Sunnis and Shiites in Aicha Bakkar and Barbir-Corniche El Mazraa. Intra-sectarian confrontations will also take place among Shiites (mainly in Dahye, such as Borj el Brajne, Ghobeiri, Chiayah, Haret Hraikk, Hay es Sellom), Sunnis (in Tariq El Jdidee, Cola, and Mazraa), and Christians (mainly in Mirna Chalouhi area).

General Impact

Displacement: Mass displacement is unlikely; however, increasing numbers of people are expected to migrate internally, either to avoid hotspot areas, to seek cheaper rents, or to move to agricultural areas where they can be more self-sufficient. Those residing in the capital, for example, will likely move to their villages and towns of origin in the South, Jabal, or North.

Forced Eviction: Unemployment and increased living costs will cause a surge in homelessness, as many will not be able to afford rent. In Beirut, some people will move to cheaper areas, such as Sabra, Hay es Sellom, Mraiji, Lailake, Karantina, Hayy el Lija; those who have lost all sources of income will be pushed to the streets. Children and women are of particular concern, especially those who don’t have extended families with whom they can stay. Risk is also high for all refugees and migrant workers due to their precarious economic situation.

- Mass evictions targeted towards Syrian refugees, already taking place in several areas. Access to adequate shelter, food, clean water, NFIs and job opportunities are major concerns, in addition to protection risks such as worsened psychological wellbeing and SGBV especially towards females. Risk for children include increased child labour – under exploitative conditions, malnourishment, and negative impact on their mental health.

- Due to the deteriorating economic situation and the unanimous political decision to push for returns, Syrian refugees are also at high risk of refoulement. This exacerbates protection concerns due to ‘unsafe’ returns, including the risk of arrests, military conscription, torture and sexual abuse and rape.[18]“Syria: ‘You’re going to your death’ Violations against Syrian refugees returning to Syria”, 7 September 2021, Amnesty International. Available At: … Continue reading Some also disappear, and children are at risk of separation from their caregivers. Of note, the dire economic situation is pushing some Syrian refugee families to return ‘voluntarily’ to Syria as they seek a more affordable and manageable living situation; in many cases, female Syrian refugees (sometimes accompanied by their children) are returning to Syria alone to secure the return of male family member, but many end up facing the same aforementioned protection concerns.

Health: Mortality rates are expected to increase, due to limited access to health services and medications. Cases of food poisoning and critical oxygen shortages for those who need oxygen machines are already taking place because of electricity cuts and are expected to increase. The reduced capacity of hospitals will prevent them from providing an adequate response to the high number of injuries and fatalities resulting from armed clashes. Healthcare for children will also be compromised with shortages of medicines and vaccines; children with disabilities and mental health conditions will particularly be affected by the shortage of medications, specialized services and assistive devices, as well as their increased cost which renders them unaffordable to many caregivers.

MHPSS: Rising tensions and violence impact the mental health of civilians whereas services become increasingly unaffordable and required medications unavailable and costly.

WASH: Lack of access to safe water will increase the risk of water-borne diseases; shortage in waste management services and in hygiene items will also increase the risk of diseases and impact the health of individuals and communities.

Winter: Lack of fuel, gas, and electricity will have a severe impact on the population during the winter, especially in the North and Bekaa areas, with additional risks to new-borns and children. In Beirut, winter will mostly affect the homeless and those in inadequate housing — in Palestinian camps, Sabra, Hay es Sellom, Hayy el Lija, Borj el Brajne, Lailake, Karantina, and Nabaa, for instance. Areas affected by the Beirut Port explosion should also be considered at risk.

Casualties: A surge in armed confrontations will result in an increased number of fatalities and injuries, many of which will likely lead to disabilities. Children will be at high risk of stray bullets, associated mental health concerns, and recruitment into armed groups.

Food Insecurity: A critically high percentage of the population will suffer from food insecurity as conflict develops. Children are at heightened risk of malnutrition. According to UNESCWA, as of September 2021 82% of Lebanese households face multidimensional poverty, and 40% (~1.65 million individuals) face extreme multidimensional poverty.[19]“Multidimensional poverty in Lebanon (2019-2021)”, UNESCWA, September 2021. Available at: … Continue reading It is conceivable that up to 70% of households move from multidimensional poverty to extreme multidimensional poverty in the event of an escalation in armed clashes.

NFIs: Rising poverty levels render many households unable to access basic NFIs such as house-hold essential items and clothing.

Gender-Specific:

- Period Poverty: Many people who menstruate are already struggling to access sanitary products. According to Dawrati, a local initiative, two-thirds of Lebanon’s adolescent girls are unable to purchase sanitary products; many are using newspaper, toilet paper, or old rags instead of pads.[20]“Women face period poverty as Lebanon’s economic crisis deepens,” 1 July 2021, France 24. Available at: … Continue reading

- SGBV: Girls will be at heightened risk of early marriage, as families in destitution seek to marry them off to lessen economic burdens. This will consequently increase the risk of domestic violence, including intimate partner violence. The economic situation will also push higher number of females into prostitution. As violent crime rates increase and as security forces become less effective, rape and sexual violence is expected to increase.

Impact on Children

Child Recruitment: Children aged 14 years and older will increasingly be recruited into newly formed communal armed groups to take part in the protection of their communities, as well as to man unofficial checkpoints. This has already been witnessed in Tripoli and Akkar; it is also rampant in the established militias of some of the traditional political parties, such as Hezbollah. As arms are already proliferated in Lebanon, more children will likely carry arms for individual use and protection. Children are also at risk of being involved in individual armed clashes and of being exploited in petty/informal dangerous acts such as delivering/transporting weapons.

Killing and Maiming: Children recruited in communal armed groups are at very high risk of being killed or maimed while, as noted above, access to services and devices for individuals with disabilities become restricted and unaffordable. Other children are also at risk of collateral impact of armed confrontations in the designated hot spots.

Mines and ERWs: Lebanon still suffers from landmines and ERWs left behind during the civil war. Contamination, mainly in fields located in rural and mountainous areas, is likely to increase and impact the wellbeing of civilians, as well as livelihoods related to agriculture.

Detention of Children: Several cases of security forces detaining children during protests have been recorded; this is likely to increase given the expected surge in overall violence. Communal armed groups are also likely to detain children, especially within the context of familial or sectarian clashes.

Trafficking and the Worst Forms of Child Labour: Given the dire economic situation, children are at heightened risk of different forms of exploitation, such as prostitution and child labour under harsh and exploitative conditions. Children are also at increased risk of being exploited in drug trade on behalf of both armed groups and groups resorting to illegal means to make profit. Armed groups, including extremist groups, may also use drugs to lure children into recruitment and to politically and ideologically indoctrinate them; such practices have already been confirmed in Palestinian camps and in Tripoli among certain extremist groups. Moreover, several recent arrests of drug traders by security forces confirmed the involvement of children as young as 15 years old, pushed by destitution to earn an income from any available source.

Education: A surge in the number of out-of-school children, especially girls, is expected. Conditions in schools, especially governmental ones, are of concern, as basics such as heating and AC will be mostly unavailable.

2- The ‘Optimistic’ Status Quo

Best-Case Scenario – Less Likely

This scenario assumes a more optimistic trajectory for Lebanon. Politically, the newly elected government holds, and manages to agree on an economic reform package. The most deeply politicised and sensitive sectors are reformed in the interest of securing international support. However, political parties retain control of less sensitive ministerial files in order to maintain patronage networks vital to their power.[21] “Lebanon Scenario Plan,” COAR, July 2021. Available at: https://www.coar-global.org/lebanon-2/

In the mid-term, parliamentary elections will take place, despite some delays; several independent groups and individuals manage to win several seats, thereby pacifying the public. Hezbollah’s decision-making power is diminished to mitigate implications on the economy (with respect to sanctions and opposition to the IMF), however, Hezbollah retains considerable influence within Lebanon and the government through allied parties. Once all these conditions are met, the government succeeds in accessing some international loans and aid.

Economic recovery will be painful. The government will attempt to float the rate and stabilise the lira at 15,000-20,000 LBP/USD. The economic plan will likely include a shift towards a more stable local economy less dependent on credit and imports and more based on sustainable local production and local technical capacities. Finance and business reform measures at numerous levels will take place, to include registration, regulation, taxation, foreign direct investment, and legal protection. A subsidies scheme will be formulated whereby ration cards are provided for the most vulnerable to access food, fuel, and medicines; some form of subsidisation is retained for items such as medicines for chronic illnesses. Plans will likely be made for a longer-term social safety net, although the actual implementation of these plans is doubtful in the short term. Finally, key reforms — such as reductions in state salaries and increased service costs — will be required but these will be extremely painful and likely result in continued political upheaval.

Security remains precarious, as there are continued regular protests and occasional instances of sectarian or political violence. Extreme unrest, such as that witnessed in Tripoli and Beirut, is also expected, albeit in an ad hoc manner that is localised and ends abruptly. Occasional and spontaneous armed clashes also continue to take place for economic, political, or familial reasons. Nonetheless, security forces manage to uphold the country’s security and maintain the role of the state as the central actor in security governance.

3- History Repeats: Full-Fledged Civil War

Worst-Case Scenario – Least Likely

In this scenario, Lebanon devolves into a wide-scale civil war. Appetite for open confrontation is currently low and there is a clear consensus on the part of Lebanon’s political leadership that open sustained conflict will not be pursued. However, this scenario operates under two assumptions: Firstly, miscalculations must always be accounted for and single acts, such as the assassination of a prominent political or religious figure, may spark a war. Secondly, this scenario assumes that the economic situation becomes intensely dire — sparking a famine, for instance — which will ultimately trigger wide-scale armed clashes that will rapidly take on a sectarian character.

Politically, the newly elected government collapses and plunges the country into yet another political vacuum. The upcoming May 2022 elections are unlikely to take place, and the parliament extends its term. In October 2022, the president seeks to extend his mandate either through another term or by handing the presidency to his son-in-law and political heir, Gebran Bassil.[22] “The Contest for Lebanon’s Presidency,” NewLines Institute, 17 March 2021. Available at: https://newlinesinstitute.org/iran/the-contest-for-lebanons-presidency/

Naturally, economic reform doesn’t take place and access to foreign loans and aid remains locked.

The economic situation becomes extremely dire. The exchange rate exceeds 50,000 LBP/USD, accompanied by surges in prices of all basic items, to include food, fuel, water, and medication. Import levels reach their lowest point, causing an unprecedented shortage of basic items. Food insecurity and poverty levels spike, with famine spreading in several areas. Services operate at the bare minimum, causing social and living standards to severely deteriorate.

Popular anger takes the form of violent demonstrations and riots protesting the political and economic situation. However, traditional political parties are quick to capitalize on the situation and regroup and arm their militias. Conflict dynamics largely mimic that of the civil war in terms of actors and frontlines, with the added factor of Hezbollah. Following is a loose structure of the geographical and sectarian shape of the conflict:

- Beirut: See most likely scenario above

- Khalde, Naame, Damour, Jiye towns and surroundings: Sunni vs Shiite vs Druze groups

- Saida: moderate Sunni groups vs extremist groups, and Sunni vs Shiite groups

- South and El Nabatieh: Intra-Shiite conflicts possible, but unlikely

- Bekaa: Mainly Sunni vs Shiite groups but also involving Christian communities

- Baalbek-El Hermel: Intra-Shiite conflict possible, but unlikely

- Akkar: Mainly intra-Sunni but might also involve Christian and Shiite groups

- Tripoli: moderate Sunni groups vs extremist groups, and Sunni vs Shiite groups (Jabal Mohsen/Tabbaneh)

- Jabal: Intra-Druze and Christian vs Druze

- Northern Coastline: Mainly intra-Christian with some Shiite vs Christian conflicts in areas like Jbail

References[+]

| ↑1 | “Lebanon Sinking into One of the Most Severe Global Crises Episodes, amidst Deliberate Inaction,” World Bank, 1 June 2021. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2021/05/01/lebanon-sinking-into-one-of-the-most-severe-global-crises-episodes |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑19 | “Multidimensional poverty in Lebanon (2019-2021)”, UNESCWA, September 2021. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/21-00634-_multidimentional_poverty_in_lebanon_-policy_brief_-_en.pdf |

| ↑3, ↑15 | See: “Robberies, murders, suicides, and road accidents (2019-2020),” The Monthly, 1 March 2021. Available at: https://monthlymagazine.com/article-desc_4961_robberies-murders-suicides-and-road-accidents-2019-2020 |

| ↑4 | “Lebanon: Assessing Political Paralysis, Economic Crisis and Challenges for U.S. Policy,” United States Institute of Peace, 29 July 2021. Available at: https://www.usip.org/publications/2021/07/lebanon-assessing-political-paralysis-economic-crisis-and-challenges-us-policy |

| ↑5 | “Lebanon Crisis Response Plan 2017-2021 (2021 Update),” United Nations and the Government of Lebanon. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/LCRP_2021FINAL_v1.pdf |

| ↑6 | “North & Akkar Governorates Profile,” OCHA, October 2018. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/North-Akkar_G-Profile_181008.pdf |

| ↑7 | “Lebanon Crisis Response Plan 2017 – 2021 (2021 Update).” Available at: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/LCRP_2021FINAL_v1.pdf |

| ↑8 | For some examples of the vandalisation of banks, see: “Angry Protesters Vandalize Banks in Lebanon,” The Daily Star, 28 April 2020. Available here: http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Lebanon-News/2020/Apr-28/505079-angry-protesters-vandalize-banks-in-lebanons-sidon.ashx; and “People Just Stormed the Lebanese Swiss Bank in Beirut,” The 961, 28 June 2021. Available here: https://www.the961.com/depositors-storm-lebanese-swiss-bank/ |

| ↑9 | Dana Khraiche and Ainhoa Goyeneche, “Lebanese Inflation Hits Record High as Food Prices Soar 400%,” Bloomberg, 12 February 2021. Available here: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-02-11/lebanese-inflation-hits-record-high-as-food-prices-soar-400 |

| ↑10 | See: “Clashes Over Car Refuelling Results in 12 Injuries in Ez Zahrani,” Lebanon 24, 30 June 2021. Available here: https://www.lebanon24.com/news/lebanon/838447/12 |

| ↑11 | “Poverty and Wealth Disparities,” Social Watch. Available at: https://www.socialwatch.org/node/10767 |

| ↑12 | Michael Young, “A Military Lifeline,” Carnegie Middle East Center, 16 June 2021. Available here: https://carnegie-mec.org/diwan/84756 |

| ↑13 | oseph Habouch, “Deteriorating Lebanon concerns U.S. officials after army warns of ‘social explosion’,” Al Arabiya, 8 March 2021. Available here: https://english.alarabiya.net/News/middle-east/2021/03/09/Lebanon-crisis-US-officials-concerned-over-security-situation-in-Lebanon-after-army-chief-warning |

| ↑14 | “Army holds on to neutrality as chaos spreads across Lebanon,” The Arab Weekly, 10 March 2021. Available here: https://thearabweekly.com/army-holds-neutrality-chaos-spreads-across-lebanon |

| ↑16, ↑21 | “Lebanon Scenario Plan,” COAR, July 2021. Available at: https://www.coar-global.org/lebanon-2/ |

| ↑17 | Ibid. |

| ↑18 | “Syria: ‘You’re going to your death’ Violations against Syrian refugees returning to Syria”, 7 September 2021, Amnesty International. Available At: https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/mde24/4583/2021/en/ |

| ↑20 | “Women face period poverty as Lebanon’s economic crisis deepens,” 1 July 2021, France 24. Available at: https://www.france24.com/en/middle-east/20210701-women-face-period-poverty-as-lebanon-s-economic-crisis-deepens |

| ↑22 | “The Contest for Lebanon’s Presidency,” NewLines Institute, 17 March 2021. Available at: https://newlinesinstitute.org/iran/the-contest-for-lebanons-presidency/ |