Conflict Analysis – Tripoli

Background

The following section provides a conflict analysis of Tripoli, one of Lebanon’s most volatile cities. Located in the north of the country, Tripoli is one of the poorest and most deprived areas of Lebanon. It has been economically and politically marginalised in Lebanon’s modern history, and marred by years of sectarian conflict, the proliferation of armed groups, and a noticeable presence of Islamic extremists. Of note, Tripoli was one of the first areas to host Syrian refugees; they are concentrated in impoverished urban areas such as Abou Samra, Trablous Zeitoun, Qoubbe, Tabbaneh, and El Beddaoui.[1]“Syria Refugee Response, Lebanon: North Governorate, Tripoli, Batroun, Bcharreh, El Koura, El Minieh-Dennieh, Zgharta Districts (T+5),” UNHCR, 31 March 2021. Available at: … Continue reading These Syrians were preceded by Palestinian refugees, who reside mainly in the Beddawi camp. Initially, Syrians were widely accepted in Tripoli due to the cultural and religious values they share with the host community. More recently, however, tensions have risen due to the economic crisis and its impact on the host community.

Tripoli’s conflict dynamics are often explained as being a by-product of the Lebanese Civil War, which primarily involved a conflict between the Sunnis and Alawite communities. In the 1970s, the two sects supported different warring sides: the Sunnis overwhelmingly supported the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO), whereas the Alawites supported the Syrian army; armed confrontation resulted in the occupation of the city by the Syrian army, which suppressed all opposing Sunni groups.[2] “The Roots of Crisis in Northern Lebanon,” Carnegie Middle East Center, April 2014. Available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/files/crisis_northern_lebanon.pdf

Sunni groups and parties briefly regained influence from 1982 to 1985, through the newly established Islamic Unification Movement (Al Tawheed). Shortly afterward, however, in December 1986, the Syrian army — supported by the Arab Democratic Party (ADP), an Alawite armed group — retaliated by conducting a large-scale massacre of the Sunni population in Tabbaneh, killing hundreds.[3] “Northern Lebanon’s Urban Proxy War,” The Fares Center for Eastern Mediterranean Studies, Available at: https://sites.tufts.edu/farescenter/northernlebanonsurbanproxywar/

The resulting resentment of the Sunni community in Tripoli towards their Alawite neighbours has manifested in violent clashes between Tabbane and Jabal Mohsen since May 2008, after Hezbollah seized control of several areas in West Beirut. These clashes have further intensified since the start of the Syrian war in 2011, as each of the areas took sides (Tabbane supporting the Syrian opposition and Jabal Mohsen supporting Assad’s regime).

It is important to understand the grievances of the Sunni community in order to comprehend the dynamics of Tripoli’s conflict.[4] Sunnis make up more than 90 percent of Tripoli’s population, with the rest made up of Alawites and Christians.

Years of neglect have fuelled feelings of distrust and anger towards the state and its institutions, with many accusing it of upholding the interests of other sects, such as the Christians or Shiites, while marginalising Sunnis.[5] “The Roots of Crisis in Northern Lebanon,” Carnegie Middle East Center, April 2014. Available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/files/crisis_northern_lebanon.pdf

More worrying is the Sunni Tripolitan’s growing resentment of state security apparatuses, particularly the LAF. The perception within this community is that the LAF disproportionately crack down on Sunni extremist figures and groups while not taking similar action against Hezbollah.[6]“Youth and Contentious Politics in Lebanon: Drivers of Marginalization and Radicalization in Tripoli,” Search for Common Ground, June 2019. Available at: … Continue reading Moreover, the fragmentation of the Sunni political and religious leadership in Lebanon has paved the way for more radical and anti-state groups to take root in Tripoli. Salafists, as well as groups and individuals affiliated with ISIS or Al Qaeda, have exploited the Sunni leadership vacuum in Tripoli and rendered many Sunnis sympathetic to their critique of the state, especially in poverty belts such as Tabbaneh, Mankoubin neighbourhood, and Qoubbe.[7] “The Roots of Crisis in Northern Lebanon,” Carnegie Middle East Center, April 2014. Available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/files/crisis_northern_lebanon.pdf

This has resulted in a series of bombings and suicide attacks in the city, as well as the uncontrolled proliferation of community-level armed groups, many of which are controlled by political figures, and several of these groups are increasingly contesting each other’s power in the city.

Tripoli, therefore, has three main conflict vectors:

- Sectarian (Sunni/Shiite)

- Resentment towards the state

- Power struggle by political figures and non-state armed groups

Stakeholders

| Type | Name / Presence /Role | Impact on Programme | Recommendations | |

|

Traditional political parties and individuals |

Christian |

Marada | Potential spoilers:

|

|

| Free Patriotic Movement | ||||

|

Sunni |

Future Party | |||

| Azm Movement (led by Najib Mikati) | ||||

| Dignity Movement | ||||

| Jamaa’ Islamiyya (a branch of the Muslim Brotherhood) | ||||

| Association of Islamic Charitable Projects (Al Ahbash): Close to the Syrian regime and Syrian intelligence | ||||

| Islamic Unification Movement (Al Tawheed) | ||||

| Mohamad Safadi (individual politician) | ||||

| Ashraf Rifi (individual politician /former ISF Director ) | ||||

| Other | Syrian Socialist Nationalist Party (SSNP) | |||

| Lebanese Communist Party (LCP) | ||||

| Alawite | Baath Party (in Jabal Mohsen) | |||

| Arab Democratic Party (ADP) (in Jabal Mohsen) | ||||

|

Other organised armed groups |

Lebanese Resistance Brigades (Saraya Mokawame): Made up of local non-Shiite strongmen who support and are supported by Hezbollah in areas where there is no Shiite population. In Tripoli, they finance several armed groups and individuals. | |||

| Nasserite Arab Movement (Haraket Al Naseriyyen Al Arab): Led by Al Nashar family (affiliated with the Lebanese Resistance Brigades) | ||||

|

Sunni figures |

Sheikh Bilal Dokmak (Salafist Ideology): main presence in Abou Samra | Potential Spoilers:

|

|

|

| Ziad Allouki (Conservative): Main presence in Al Barraniyye neighborhood | ||||

| Husam Murad (Conservative): Leads the Shabab Al Khityar group, which is armed and mainly present in Al Zahirieh | ||||

| Saad Al Masri: Leads an armed group of over 800 men in Tabbaneh | ||||

| Extremist Sunni armed groups | Jud Allah: Presence in Qoubbe and Abou Samra | |||

| Salafists | ||||

| Khan Al Askar Armed Group: Located in Khan Al Askar area) | ||||

|

Security institutions |

Internal Security Forces | Potential Stabilizers:

Potential Spoilers:

|

|

|

| Lebanese Armed Forces | ||||

| Lebanese Armed Forces – Intelligence Directorate | ||||

| Internal Security Forces – Information Branch (Intelligence) | ||||

| Municipalities | Al Fayhaa Municipality Union: Tripoli, El Mina, El Beddaoui and Al Qalamoun municipalities. Ouadi En Nahle has its own separate municipality.

Municipalities have a secondary role in Tripoli’s communities and are seen as incapable of providing required services. |

Potential Stabilizers:

Potential Spoilers:

|

Engagement, information sharing, project design, coordination for implementation

Mitigate:

|

|

| Sunni tribes | Mainly concentrated in Ouadi En Nahle and El Beddaoui. Al Seif tribe is the biggest in Wadi Nahle and is affiliated with Karame. | Potential Stabilizers

Potential Spoilers

|

|

|

| CSOs & NGOs | Heavily present in the area, providing both development and humanitarian services. Though the majority target both Lebanese and Syrians, the host community’s dismay has been growing due to the worsening economic conditions. | Potential Stabilizers:

Potential Spoilers:

|

|

|

| Activist groups / individuals | Tripoli has been dubbed the Bride of the Revolution and has, in many instances, been the catalyst for protests across the country. However, due to the fragmented nature of the area, and the inability of revolutionary groups to effectively coordinate and mobilize, both political and Islamist groups have started infiltrating and exploiting them.

For example, sources report that Hurras Al Madina, founded initially to respond to the waste crisis in Tripoli, has now become affiliated with the Jamaa’ Islamiya. |

Potential Stabilizers

Potential spoilers

|

|

|

Despite the length of the list, only the key actors are cited here; there are multiple other individuals and groups in different areas, such as Hadid, Bab Al Ramel and Qoubbe. If anything, the list is indicative of the entrenched divisions within Tripoli’s neighbourhoods and surrounding areas.

Scenarios

1. A De-Facto Statelet

Pessimistic – Most Likely

This scenario assumes that Tripoli will fall out of the control of the Lebanese state and turn into a de facto statelet. Worsening economic conditions plunge residents into extreme poverty and levels of despair. The state, which has always marginalised Tripoli, becomes nearly absent due to a lack of resources and an inability to provide the most basic items and services. This further exacerbates the economic and social grievances of the population. More critically, the state suffers from the hollowing out of its security services, as resources are stretched thin and funds can barely sustain proper functionality; the LAF and ISF will still maintain a presence in the area, however, they will be increasingly unable to maintain order and to prevent the formation and empowerment of vigilante groups. Of note, following the spillover of Syria’s war in 2011, security forces barely managed to contain the situation in Tripoli — and that was at a time when the country’s economy was stable and protests, roadblocks, and riots were almost absent across Lebanon.

In June 2021, when violent riots erupted over severe electricity outages, large groups of armed individuals took to the streets in Tabbaneh, Qoubbe, Tal, Jessrine, El Beddaoui, Mankoubin, and Abou Samra, shooting in the air and forcing shops to close. The LAF eventually entered Tripoli district to control the volatile atmosphere, but they were forced to briefly pull out of some areas, including Tabbaneh, to avoid armed confrontations with angry residents. As economic conditions worsen and the state’s ability to maintain order and security diminishes, such incidents will reoccur, and the LAF will most likely not be able to enter the area at all. These factors will ultimately force communities to resort to both self-governance and self-security — “amen zati”. In order to fill the governance void, each community will form an independent committee that will regulate and coordinate service provision and the affairs of the area. Armed vigilante groups, which have already formed in several Tripoli areas, such as Qoubbe and Tabbaneh, will proliferate such that each area controls and maintains its security. Traditional political parties will continue to exploit the situation by funding these newly formed groups and committees, in an attempt to maintain influence in these areas and gain more power than their competitors. Geopolitical influence and funding will also play a critical role, as nations that already back different politicians in the North — such as Turkey and Saudi Arabia — will determine the division of power across communities and shape the competition over power and influence. Moreover, this new, volatile environment will act as a safe haven and fertile ground for extremist armed groups — the proliferation of which have already been seen in Tripoli.

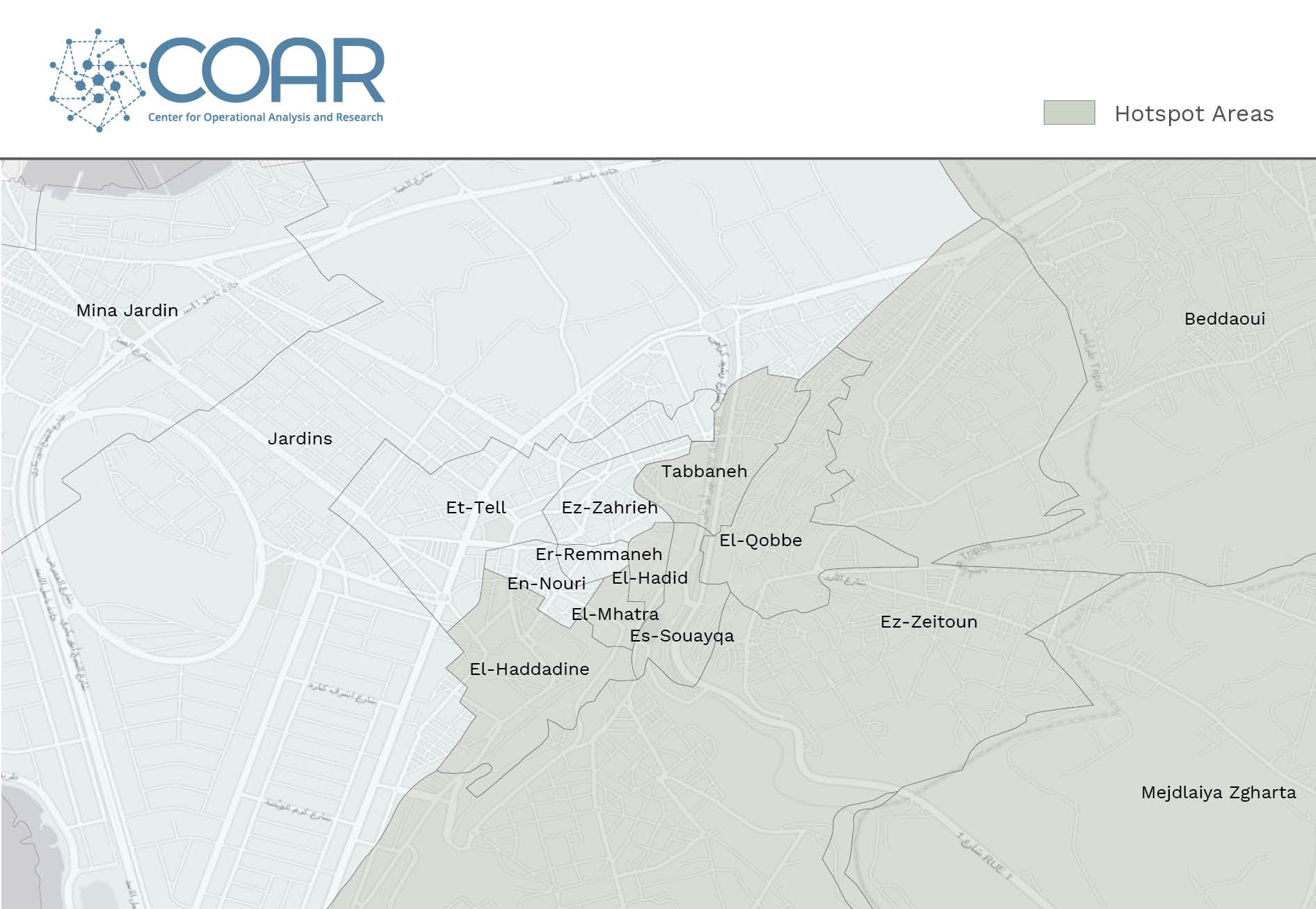

Conflict Dynamics

De facto statelets and communal instability will largely take place along the whole eastern line of Tripoli, which mostly consists of impoverished areas. These include: Tabbaneh, Qoubbe, Hadid, Jessrine, Hdadine, Abou Samra, Trablous Zeitoun, and Jabal Mohsen. The conflict dynamics are as follows:

Armed clashes within and between communities: The proliferation of both vigilante and general armed groups will create a competitive atmosphere both within and among communities, as they seek to retain power and influence. Clashes will also take place between groups of opposing patronage networks, such as in Qoubbe between Al Tawheed (currently funded by Iran) and Jund Allah (Salafist, supported by Saudi Arabia).

Armed clashes with the state’s security apparatuses: The state will exert effort to maintain control over these areas, which will lead to frequent armed confrontations with armed community-based groups, whose resentment towards the state’s security apparatuses is already mounting.

Armed clashes with Islamist groups: Extremist Sunni Islamic groups are likely to clash with more moderate or conservative groups, with the goal of asserting their influence and attempting to render Tripoli an Islamic state; they will also clash with their traditional foes, mainly groups aligned with Iran or Syria (ADP, SSNP, Lebanese Resistance Brigades, Baath party).

Armed clashes between Tabbaneh and Jabal Mohsen: This frontline will be constantly active. The Alawites will be more vulnerable than ever, given the near total absence of the state and their complete encirclement by Sunnis.

Rising threat of asymmetrical attacks: The proliferation of, and assertion of control by, several extremist groups will most likely lead to a resurgence of asymmetrical attacks, such as vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices as well as suicide attacks.

Impact: Refer to the “General Impact” section in the national scenario. Note the following specific impacts for Tripoli:

Displacement : Many residents, including Syrian refugees, residing in the eastern part of the area will opt to escape the conflict and instability. Those displaced will likely move east to Deir Amar and El Minie, as well as Akkar. Christians are most likely to move to Zgharta. There is also a distinct concern regarding unsafe economic migration to Europe, as Tripoli is a key jumping off point for European illegal migration.

Restricted humanitarian access: While the humanitarian situation will worsen, NGO access will be limited, and organisations’ ability to reach the most vulnerable groups and individuals will be impacted. A remote partnership modality with locally based CSOs and NGOs is advised. In particular, relationships should be – likely simultaneously – formed with municipal officials, local security officials, local activist networks, and potential growing armed groups in areas of operation (see Stakeholder analysis for detailed recommendations).

Recruitment of youth and children: while noted as a potential impact in the National Conflict Analysis, the risk of children and youth recruitment significantly increases in Tripoli due to the larger number of both moderate armed groups and Islamic extremist groups. This has already been confirmed by several reports and studies.[8]“Youth and Contentious Politics in Lebanon: Drivers of Marginalization And Radicalization In Tripoli,” Search for Common Ground, June 2019. Available At: … Continue reading

2. A Worsened Status Quo

Optimistic – Less Likely

This scenario assumes that the political, economic, social, and security situation will worsen in Tripoli, but the state will maintain a certain degree of governance and control over the area. The worsening economic crisis will plunge a large number of residents into deeper levels of poverty and destitution. The gradual lift of subsidies renders hundreds of households unable to afford the most basic items, suffering to make ends meet. This will further affect Tripoli’s workers, as many of them have jobs in the capital and will be unable to commute to their workplaces due to the inflated price of fuel. Governmental and municipal services, already inadequate and insufficient in the North, reach an all-time low, with electricity, water, health, waste management, and other services critically impacted.

To fill the governance vacuum created by the diminishing capacity of the state, communities will resort to self-governance. On the social level, each community will likely form independent committees that will regulate and coordinate service provision and the affairs of the area – which may serve as key points of engagement for international aid actors. On the security level, this will translate into an increase in community watch groups, many of which are already in place. However, despite these groups being armed, this scenario presumes that the state’s security apparatuses are able to maintain some form of sovereignty and to prevent these groups from placing whole communities under their control. Nonetheless, the risk of the proliferation of both independent and extremist armed groups remains high, given the fertile ground for their formation and activities. Consequently, the risk of asymmetrical attacks should not be discounted — though the risk is not as high in this scenario as in the most likely scenario above.

Politically, the Sunni arena will remain divided and leaderless, which further presents an attractive environment for extremist groups to thrive. Violent protests will continue to take place, at a heightened frequency and intensity; these will most likely be met with increased force and violations by security forces, thereby exacerbating existing grievances. Of note, independent revolutionary groups, which are already divided, will be increasingly exploited by political figures and parties, as well as extremist groups.

In terms of conflict dynamics, the area will witness rising levels of unrest as armed groups will compete over power and influence; however, this scenario presumes that both political parties and armed groups have no appetite for a prolonged armed confrontation and will quickly pacify their supporters and contain the situation.

3. An ‘Islamist/Extremist’ Statelet

Worst Case Scenario – Least Likely

This scenario presumes that Tripoli will be controlled by Islamic extremist groups and declared an Islamic imara. The area will be effectively detached from the rest of the country and will exist completely outside the governance and control of the state. As noted elsewhere, Tripoli has long been a fertile ground for extremist ideology due a combination of factors: fragmented Sunni leadership, marginalisation and neglect by the state, and resentment toward security forces (particularly the LAF) due to a perception that they deal unequally with armed groups (chiefly a reference to their tolerance toward Hezbollah). Actors with extreme Sunni ideologies, such as Salafism, exploit these grievances by sowing the narrative of the state’s favouring of Christians and Shiites and complete sidelining of Sunni interests. Extremists also take advantage of the impoverished nature of many of these areas and channel a disenfranchised Sunni populism in areas such as Tabbaneh, Mankoubin, and Qoubbe. (In reality, Mankoubin neighbourhood alone has sent dozens of men to fight in Iraq and Syria, several of whom have been involved in suicide attacks).

Triggers for this scenario include the exaggerated worsening of the economic crisis, increased general chaos across the country, and near total collapse of the state’s security institutions. The rise of the Islamic state will start from the eastern part of this area and swiftly extend to cover the western parts. Though opposing armed groups exist (see stakeholder section), they will be unable to counter the new rule due to their disorganisation and the unequal balance of power. Security forces will be completely forced from this area and confined to frontlines on its outskirts. As seen in Syria, security forces are likely to besiege the area in an attempt to cut off supply lines. The area will face a dire humanitarian crisis due to its restricted access to basic items to include food, water, and medicine. Only local implementing partners will be able to maintain presence and access — though at a high risk to both staff and beneficiaries.

This power dynamic will render the country in a state of Sunni and Shiite bi-polar armed power. Other Sunni strongholds, such as Saida, Majdal Anjar, and Arsal, will send fighters to the new imara or attempt to create a similar Sunni haven in their areas. Other sects, mainly Christians and Druze, will rearm themselves in order to protect their communities. Eventually, the country is likely to devolve into an open armed conflict.

References[+]

| ↑1 | “Syria Refugee Response, Lebanon: North Governorate, Tripoli, Batroun, Bcharreh, El Koura, El Minieh-Dennieh, Zgharta Districts (T+5),” UNHCR, 31 March 2021. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Syria |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑5, ↑7 | “The Roots of Crisis in Northern Lebanon,” Carnegie Middle East Center, April 2014. Available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/files/crisis_northern_lebanon.pdf |

| ↑3 | “Northern Lebanon’s Urban Proxy War,” The Fares Center for Eastern Mediterranean Studies, Available at: https://sites.tufts.edu/farescenter/northernlebanonsurbanproxywar/ |

| ↑4 | Sunnis make up more than 90 percent of Tripoli’s population, with the rest made up of Alawites and Christians. |

| ↑6 | “Youth and Contentious Politics in Lebanon: Drivers of Marginalization and Radicalization in Tripoli,” Search for Common Ground, June 2019. Available at: https://www.sfcg.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Search-for-Common-Ground-Youth-and-Contentious-Politics-in-Lebanon.pdf |

| ↑8 | “Youth and Contentious Politics in Lebanon: Drivers of Marginalization And Radicalization In Tripoli,” Search for Common Ground, June 2019. Available At: https://www.sfcg.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Search-for-Common-Ground-Youth-and-Contentious-Politics-in-Lebanon.pdf |