Executive Summary

Although migration and displacement in Syria have often been studied from the perspective of host-country integration, the impact on those who are “left behind” is also significant, and it is seldom acknowledged, despite its commonness. Survey data collected in Damascus indicate that approximately two-thirds of Syrians have relatives who have relocated abroad since 2011, and nearly one-fifth of Syrians have relatives who have been displaced to non-Government areas. This report examines the social, economic, and mental health impacts on Syrians whose families have been broken up by the conflict. It concludes that family separation is a key underlying driver of needs, particularly economic needs. Finally, this report offers recommendations for how such data can be integrated into context-sensitive project design.

Introduction

Displacement is widely recognised as a touchstone issue of the crisis in Syria, yet the impact of population movements remains poorly studied. The consequences of displacement and migration for those who are “left behind” — that is, cut off from relatives and support networks — have rarely been studied. Instead, analysis has often focused on Syrians’ integration in host communities abroad or the prospects for return. Arguably, family separation constitutes a key overlooked impact of the conflict. Notably, Syria’s social fabric has been torn by both the outward migration of refugees and internal displacement, which is aggravated by the hardening of internal borders between Government of Syria territory and the regions controlled by the Turkish-backed opposition and the predominantly Kurdish Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). A recognition of such impacts is overdue. Donors and implementers are now rightly concerned with identifying better methods of understanding the needs, vulnerabilities, and associated targeting criteria needed to reach conflict-affected populations in Syria. Issues such as family separation will become increasingly relevant as aid actors target underlying drivers of need and as more ambitious early recovery efforts gain momentum.

This brief report seeks to fill this gap by exploring family separation in the context of an evolving crisis response. Its purpose is two-fold. First, based on quantitative survey data and contextual analysis, it assesses the impacts of family separation — including its economic, social, and mental health aspects — among respondents in surveyed Damascus neighbourhoods. It uses three lenses and assesses differences among: long-time residents of Damascus and those who have migrated to the city since 2011; women and men; and respondents of various economic strata. Second, this report seeks to inform the work of donors and aid implementers who are considering a host of broader aid response challenges. These include early recovery initiatives and stabilisation activities, as well as more general attempts to improve the context-sensitivity of implementation. Ultimately, this paper is intended to promote discussion over the ways that program designers understand needs and how aid action ultimately affects target communities. In the long term, donors, implementers, and analysts must devise analytic frameworks to support implementation that is more comprehensive and ambitious in scope. Understanding the impact of root causes of need, including family separation, will be one step in that process, enabling response actors to do more good, better.

This report is a collaboration between the Operations and Policy Center (OPC) and the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR). Its conclusions are based on survey data designed and collected by OPC among 600 respondents in three Damascus neighbourhoods, Rukn al-Din, Zahreh, and Nahr Aisha in December 2020 and January 2021. COAR has analysed the data, supplemented it with additional qualitative field data, and drafted the report, which both organisations have finalised. Although quantitative data is a fundamental aspect of needs assessments, such data are often siloed, disconnected from analytics, and seldom used to inform the wider response community or decision-makers. In some respects, this report is an open-book experiment intended to show the way disaggregated data can be used to better identify trends shaping population-level needs. It is our shared hope that such efforts can lend new perspective to changing social dynamics and contribute to more efficient means of meeting the needs of the Syrian people.

Key Takeaways

- A decade of conflict has profoundly changed the social fabric of Syria. Two-thirds of survey respondents have had family members relocate outside Syria since the crisis began. Nearly one-fifth have relatives who have moved (or have been displaced) across internal borders with non-Government areas. Although the aid community has paid little attention to the issue, half of Syrians identify family separation as a “large” source of stress in their lives.

- Irrespective of where respondents’ family members have relocated, the most pronounced impact of family separation is economic. Nearly three-quarters of surveyed Syrians report that separation from one or more breadwinners is a major source of stress.

- Female respondents report a greater impact over the loss of a breadwinner than men do. This gendered impact aggravates underlying inequalities and vulnerabilities such as shelter access and unfavourable labour market conditions.

- However, such impacts vary widely according to age, indicating the extent to which gender-sensitive implementation requires a nuanced approach, including data that is disaggregated by age, migration status, class, and other factors, in order to move beyond overly simplistic conceptions of vulnerability and need.

- Family separation factors in a deepening spiral of poverty. Migrants to Damascus are more likely to be linked to family members in opposition areas; they face heightened economic stress and precarious access to reliable shelter. Such conditions are worse for women and other vulnerable groups. Vulnerabilities such as these overlap. Over time, the negative coping strategies necessitated by extreme poverty and aggravated by the realities of life in Syria will magnify the challenges that must be addressed in a post-conflict or transitional setting. The longer Syrians endure such conditions, the harder they will have to work to achieve stability in the future.

Recommendations

- Recognise family separation as a driver of needs. Donors must view family separation as a keystone issue in Syria and a corollary of refugee return. An outright majority of previously surveyed Syrians have expressed a wish to eventually emigrate from the country.[1]Attitudes in the Syrian Capital of Damascus: A Survey in Three Neighborhoods, Operations and Policy Center (2021): … Continue reading While current structural and political conditions militate against return, donors can reduce the pressure for Syrians to migrate by addressing key needs and vulnerabilities, many of which stem from the country’s economic collapse and are exacerbated by the breakup of families.

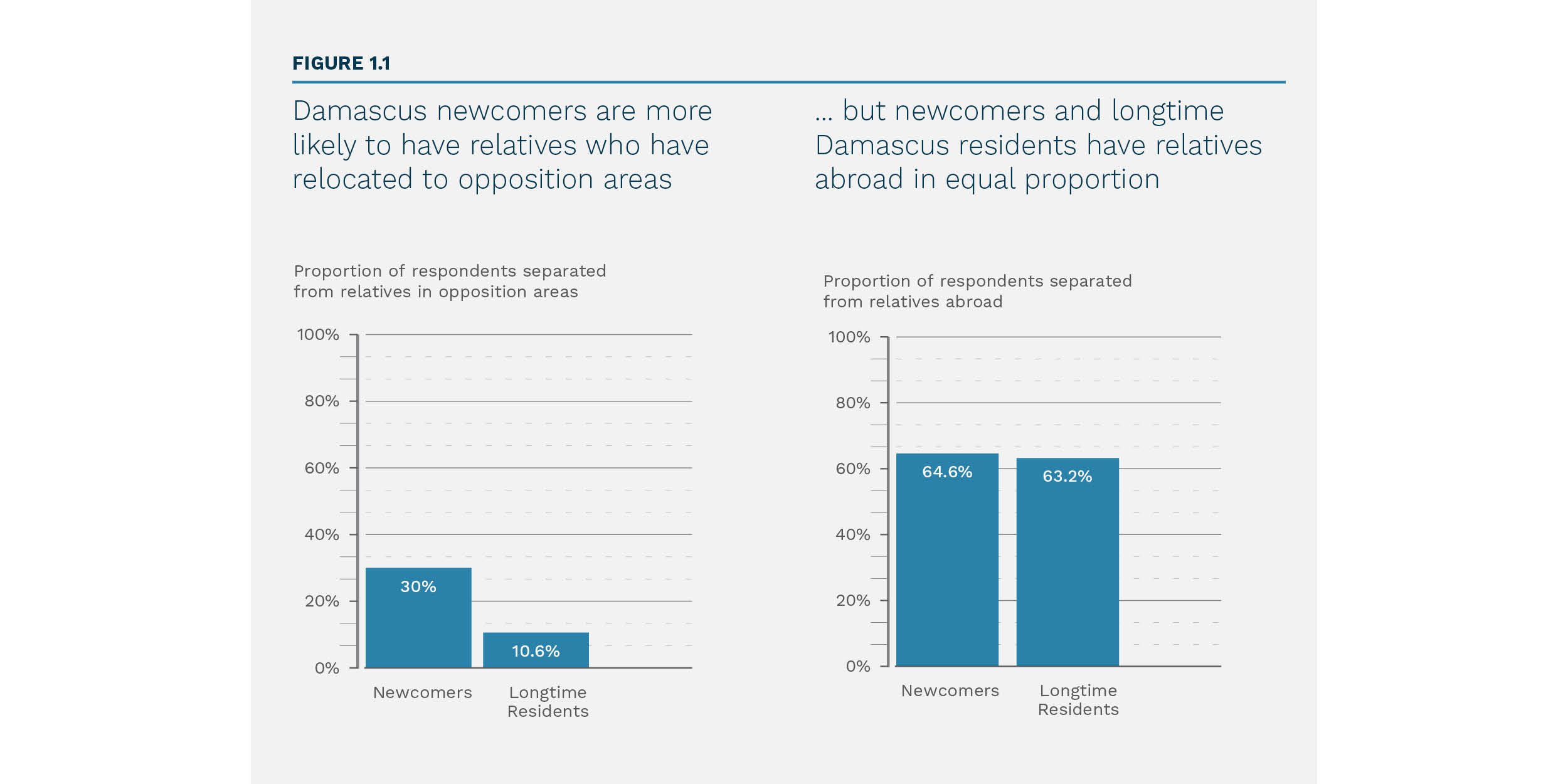

- Design activities to redress service discrimination. Implementers must direct limited aid to needy, historically disadvantaged populations, including migrants of underserved backgrounds or in marginalised areas. Historically, the Government of Syria has prioritised loyalist populations for service delivery and the allocation of scarce resources.[2]Political Demographics: The Markings of the Government of Syria Reconciliation Measures in Eastern Ghouta, COAR (2018): … Continue reading Migrants to Damascus are three times more likely than longtime residents to have relatives in opposition areas; they are at risk of neglect if state service provision is allocated in a way that punishes their perceived closeness to the opposition. Such tendencies underscore the need for programme design, area-based approaches, and context-sensitivity procedures to identify and combat systemic neglect.

- Scale up economic support. Economic needs are the foremost concern of all population groups in Syria. It behoves donors to devise more efficient and comprehensive means of providing assistance, including cash, livelihood support, cash for work, and other forms of aid. Women face particularly high levels of need, and donors must ensure that relief works targeting women do not reinforce pre-existing gender-based economic inequality. However, programs must also be sensitised for age-related needs and other variables that shape vulnerability and economic stress.

- Understand that not all cases of family separation are alike. Although such cases bring about difficult-to-quantify social, emotional, and personal costs, families with a greater number of relatives abroad report higher economic resilience. Families split across zones of control inside Syria do not enjoy the same level of access to foreign remittances as those with relatives abroad, and they face greater economic hardship as a result. Where necessary and possible, such factors should be considered in programme design, although donors must also recognise that economic stress is now pervasive and needs are nearly universal.

- Embrace quantitative data, but complement it with analysis. Donors should view quantitative research as an important aspect of the programming toolkit that — if adequately contextualised and supported by analysis — can improve decision-making and expand upon the data already collected while conducting vulnerability and needs assessments. For gender-sensitive research in particular, robust datasets and disaggregations are needed to ensure operational utility.

Understanding Impacts

Context-sensitive implementation requires understanding how a given aid intervention will affect a target community. This requires first understanding the community itself. Although the three neighbourhoods surveyed in this study are located within kilometres of each other, their internal dynamics, demographics, needs, and sensitivities differ widely. For instance, Rukn al-Din is noted for its Kurdish population, residents of Circassian origin, and relative affluence when compared to the other surveyed areas. While all surveyed neighbourhoods host IDPs, Zahreh,[3]Also known as Zahirah. is to some extent defined by the waves of displacement from nearby Yarmouk Camp, which has dramatically impacted services, including shelter access. Nahr Aisha, meanwhile, is noted for its Alawite population and its associations with the insular ethno-religious community of the Assad family, although this is not true of all residents, and the neighbourhood is seen as the most economically distressed of the three surveyed areas.

Such factors are highly localised. While Rukn al-Din has been targeted for a number of relief projects, Zahreh and Nahr Aisha have seen fewer such activities. Factors such as these shape local needs, and they should determine how aid projects are carried out. For the purposes of this study, response data from all communities have been assessed as a whole, in order to achieve a robust sample size. However, during project design it is important to disaggregate data by community and neighbourhood when possible, and implementers must be cognisant of difficult-to-quantify historical and social conditions.[4]For more on these communities, see: Living in Damascus After a Decade of War: Employment, Income, and Consumption, Operations and Policy Center (2021): … Continue reading

Understanding Family Separation in Syria: Three Lenses

Newcomers and Long-Time Residents

In several important respects, concern over long-term social cohesion and social stability in Syria is visible in conflict-era migration dynamics into and out of the capital. Newcomers to Damascus (i.e., those arriving since the outbreak of the conflict) are more alone, lonely, and under greater economic strain than are longtime residents of the same surveyed neighbourhoods. These impacts are no doubt multi-causal. Yet they also correlate strongly with the breakup of families and social networks.

On balance, Damascus has witnessed a substantial shift in population demographics since 2011. Two processes are notable in this respect. Conflict-fuelled migration has driven many Syrians abroad, particularly those with the resources, networks, and access needed to sustain the burdens of migration. In parallel, intense violence, the Government of Syria’s reconciliation strategy, and wide-scale destruction have induced rural Syrians to migrate to the capital. Many newcomers have arrived in Damascus even as members of their family have fled or been forcibly displaced to areas outside the Government of Syria’s control, along the Syria-Turkey border. Not surprisingly, migrants to Damascus have been separated from greater numbers of family members than longtime Damascus residents have. Although newcomers and longtime residents of Damascus have relatives abroad in roughly equal proportion (roughly two-thirds of respondents), newcomers are roughly three times more likely to have relatives who have relocated to opposition-held regions of Syria (figure 1.1).

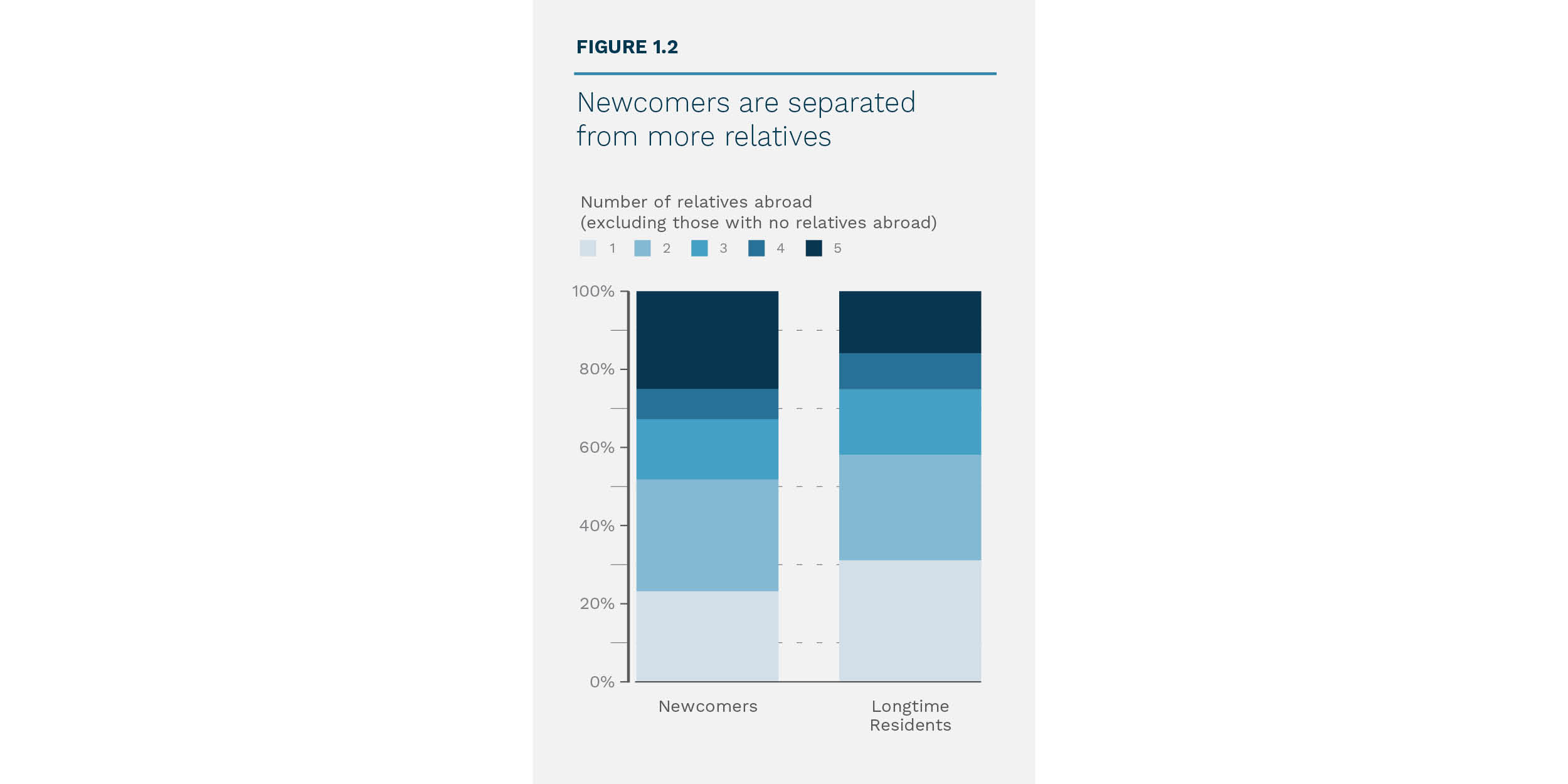

Newcomers are not only more likely to have relatives in opposition areas, they are separated from far more relatives. Indeed, 65 percent of newcomers report having at least three relatives who are separated inside the country. Among longtime residents, only 17 percent reported family separation to this degree (figure 1.2). In other words, the families of newcomers have been far more heavily fractured due to the conflict than those who have remained in Damascus. This is likely true in communities across the country.

Above All Else, It’s Economic, but Social Impacts Matter, Too

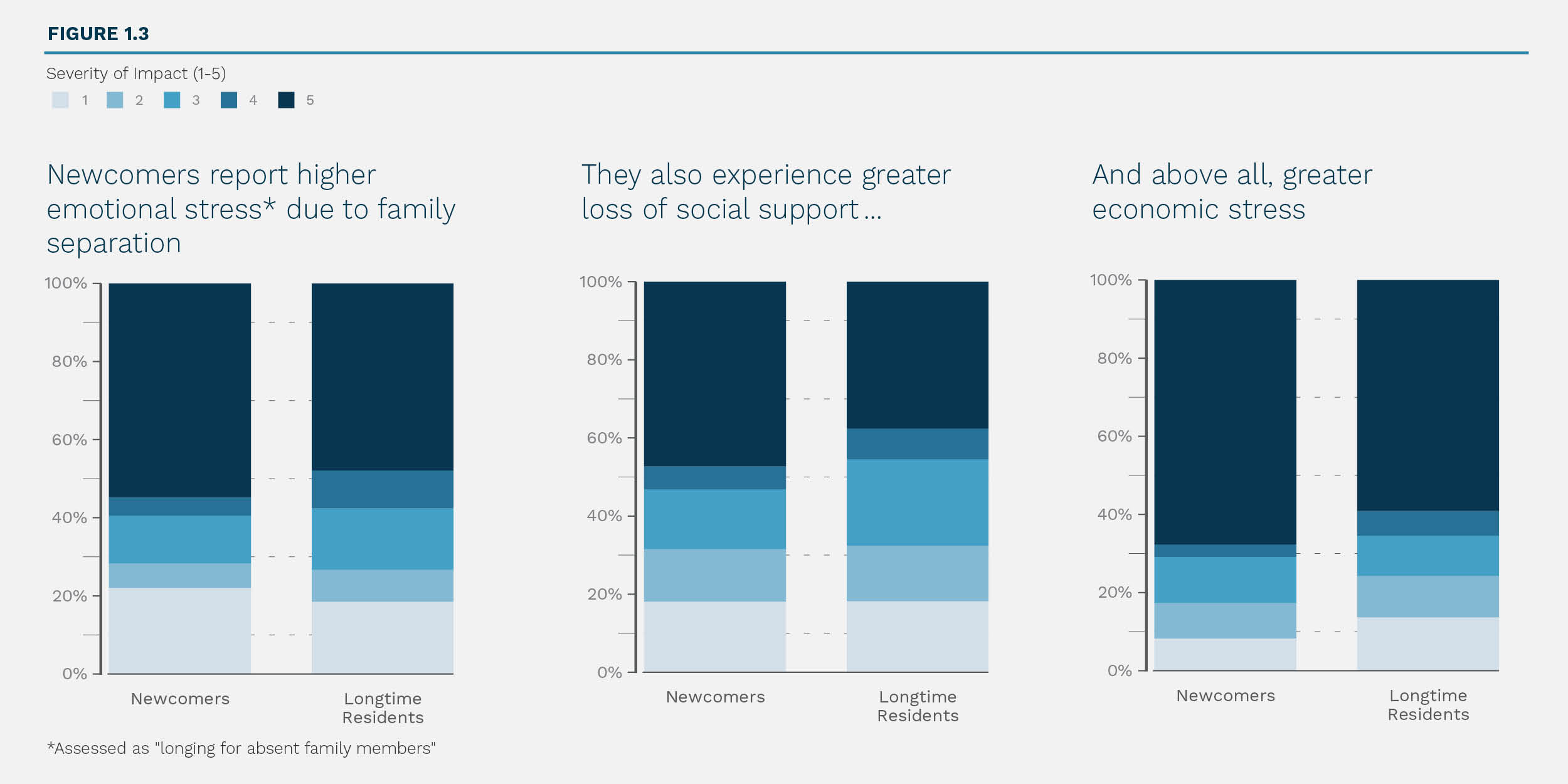

It is little surprise that economic concerns predominate among those who have been separated. Newcomers and longtime respondents alike identified the loss of a breadwinner as the most significant of the surveyed impacts they experienced due to family separation. However, newcomers identified social and mental health impacts as being far more significant sources of stress than did longtime residents (figure 1.3). As such, the fraying of family and social networks should be seen not only as the loss of a financial safety net, but as an aggravating factor in other needs, including mental health needs, which are underfunded aspects of the health sector that have often been neglected amid a focus on other, more tangible programming areas.[5]In the current case, “longing for absent family members” is used as a proxy value for mental health impacts, while the “shrinking social support network” stands in for social impacts.

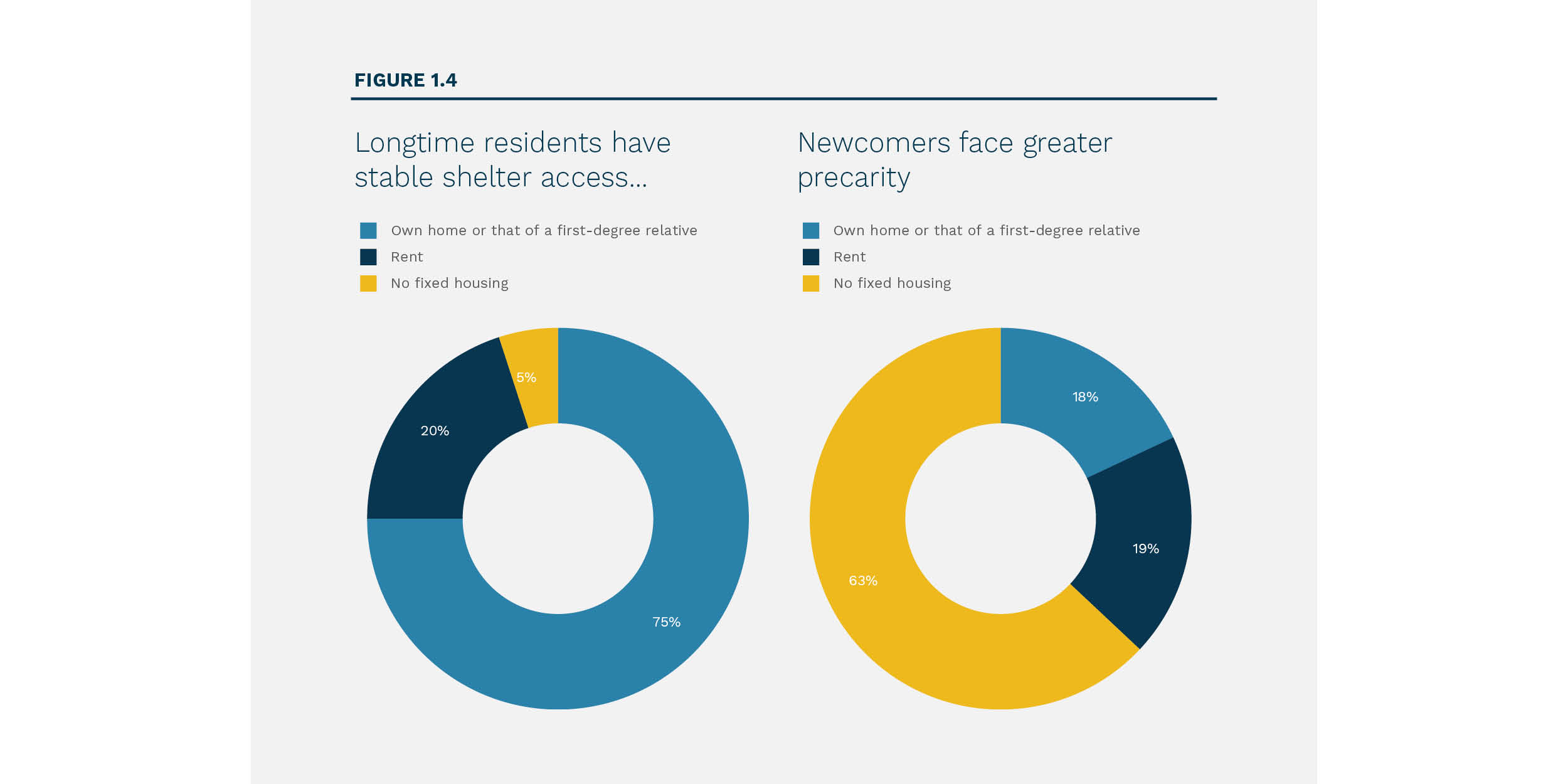

Shelter: Renters and Rentiers

Changes to population demographics in Damascus are also reflected in the stark divide between newcomers and longtime residents in terms of shelter access. As expected, longtime residents enjoy significantly more favourable housing conditions than do newcomers across every assessed metric, presenting newcomers who already face greater economic jeopardy with yet another financial hurdle. A full 75 percent of longtime residents live in their own homes or the homes of first-degree family members (figure 1.4). Presumably, these include absentee relatives who are abroad. Only 20 percent rent, compared with nearly two-thirds of newcomers. This is not surprising, particularly given that many newcomers, particularly those reaching Zahreh, for instance, arrived from Yarmouk Camp, where socio-economic conditions were already challenging. More than 18 percent of newcomers have no fixed access to shelter.

These findings have significant implications for project design. Aid implementers often use administrative boundaries (e.g. communities or neighbourhoods) as the basis of targeting for projects such as housing rehabilitation or cash for work. However, individuals’ needs within an area can vary significantly, particularly when communities have seen high degrees of outward migration and rural-urban flight. Precarious shelter access increases physical and economic vulnerability, thus compounding the risks already faced by vulnerable populations, including women and non-binary people, LGBTQ+ individuals, children, and the elderly.[6]LGBTQ+ Syria: Experiences, Challenges, and Priorities for the Aid Sector, COAR (2021): https://www.coar-global.org/2021/06/22/lgbtq-syria-experiences-challenges-and-priorities-for-the-aid-sector/. As aid actors consider long-term programming priorities — whether in a humanitarian, early recovery, or post-war setting — access to housing will be an important dimension of household economic stability. Aid implementers must be aware of the stark divides that exist among Syrians.

Gender Gaps

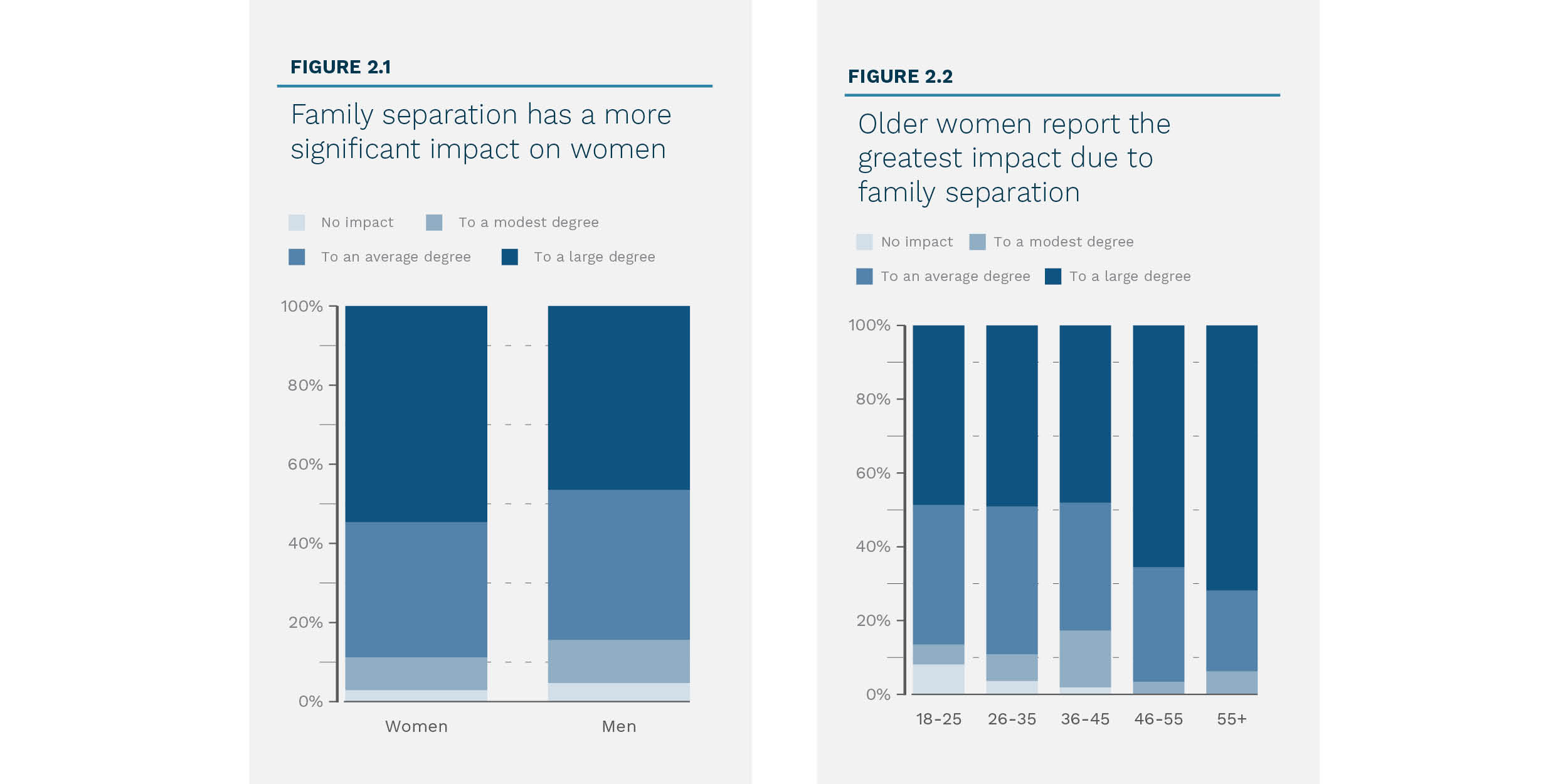

In recent decades, gender sensitivity has been recognised as a core component of donor-funded aid implementation. Despite considerable enthusiasm, however, meaningful adoption has foundered. Among the many causes of this failure is the lack of disaggregated data, particularly in Syria, where limited information has hampered efforts to move beyond simplistic conceptions of gender-related vulnerability.[7]The Business of Empowering Women: Insights for Development Programming in Syria, COAR (2020): https://www.coar-global.org/2020/05/15/the-business-of-empowering-women/. Without a basis in disaggregated and contextualised data, donor objectives risk falling out of alignment with actual needs. Not only data, but the right data analysed the right way, can help bridge existing gaps and identify specific gendered impacts of issues such as family separation. Although the data sampled here present only a snapshot view, several important gender-related trends are clear. Overall, women report feeling a more substantial impact due to family separation than men, yet this impact is not consistent across all variables. Of the three impacts assessed here — economic, social, and mental health — only in terms of economic issues do women as a whole report a more significant impact. That being said, significant age-related impacts are clear for both men and women, suggesting that age-disaggregated data will be vital to assessing needs accurately.

Mind the Gap: Gendered Implications of Separation

Women are far more likely than men — by nearly 10 percentage points — to describe the stress of family separation as impacting their lives “to a large degree” (figure 2.1). Yet these results are not uniform across the board. Older women reported such stress in far greater numbers than their younger counterparts (figure 2.2). While more research is needed to determine causality, to some extent this likely reflects the limited means of support for those who are left behind as social and family networks shrink. A similar trend is apparent among male respondents, and older men also report more severe overall impacts due to family separation than their younger male counterparts.

An Economic-Gender Divide

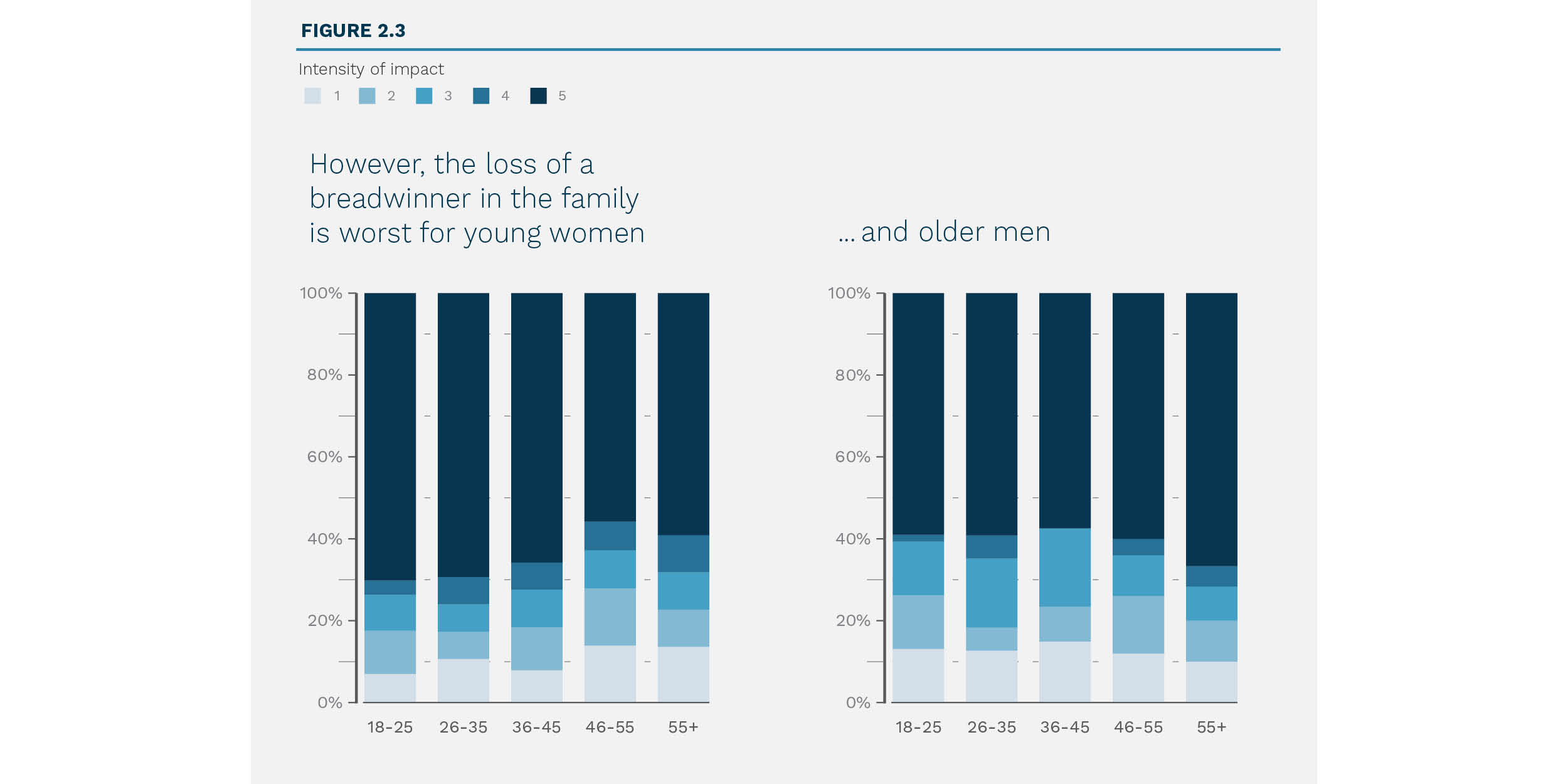

Although Syrians of all descriptions have suffered due to family separation, the economic costs have been greatest for women. Although women in Syria have low labour force participation, those who do work experience longer working hours than their counterparts in regional states or when compared with the global average.[8]Living in Damascus After a Decade of War: Employment, Income, and Consumption, Operations and Policy Center (2021): … Continue reading Yet that work does not necessarily translate to economic security. Economic opportunities that are conventionally available to women in Syria often have limited income potential. As such, the acute economic stress facing women reflects underlying factors within the Syrian labour market. However, age-related factors are once again critically important. The stress brought on by the loss of a breadwinner is highest among women under 45 years of age, while the impact is far less pronounced for older women.

This differs profoundly from the way men experience the economic and social impacts of family separation (figure 2.2). Reversing the trend among women, it is older men who reported the most acute economic pressure due to family separation. Such factors require greater study to be fully understood. It is also important to note that economic needs are universally high.

Mental Health Considerations

As a whole, women and men differ little in their self-assessment of the impact of family separation as it relates to social support or a sense of longing for absent family members. On one level, this suggests that mental health and psychosocial support programs must look beyond gender as the sole targeting criterion. As with economic considerations, age-related social and mental health impacts vary dramatically by age. Older women suffer far more in terms of mental health effects, while older men fare worse in terms of social costs.

All told, these findings demonstrate the extent to which age data may be used to refine targeting criteria based on age-related vulnerability, a key for advancing beyond simplistic, one-size-fits-all models of vulnerability. This also underscores how a gender-sensitive approach to the social and mental health impacts of family separation will require a recognition of the needs of men and boys, too.

Standard of Living

In Syria, it pays to be wealthy. The data suggest that respondents of a higher socio-economic status are able to avoid some of the costly or disadvantageous coping strategies associated with conflict and family separation.[9] Ibid. A self-reported higher standard of living correlates strongly with better shelter access, resilience against the effects of family separation, and a greater number of relatives abroad, a source of all-important foreign remittances. By contrast, respondents reporting a lower standard of living experience precarious shelter access and the need to rent or resort to dangerous shelter strategies, more severe impacts due to family separation, and fewer linkages to family members (and remittances) from abroad. Despite such differences, however, Syrians are now more impoverished and heavily reliant on remittances and aid than ever. Although implementers should ensure that programme design targets the most needy, effectively doing so will require substantial efforts to understand needs.

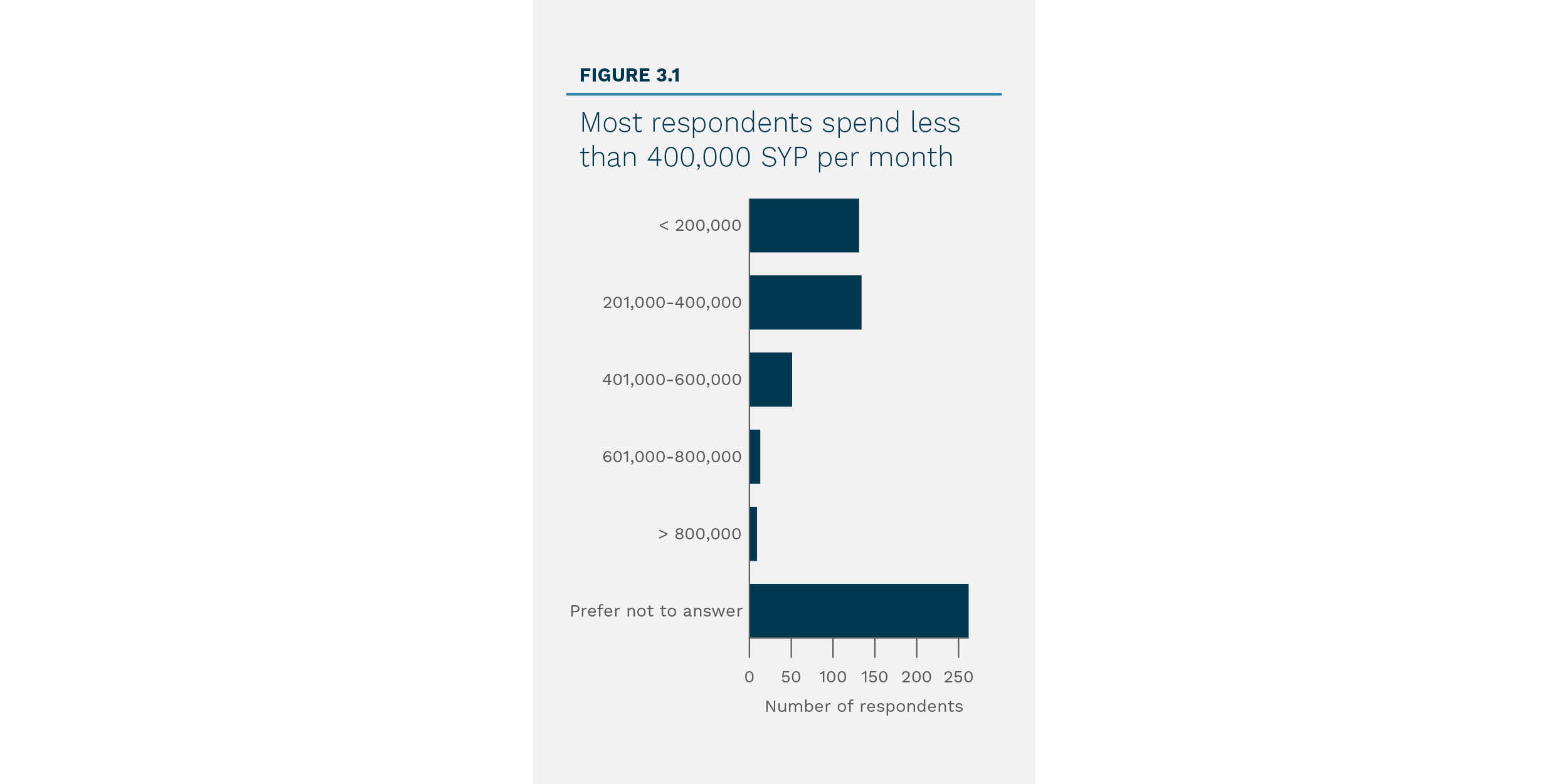

Assessing household wealth, spending levels, and economic well-being is sensitive in any context, and it is prohibitively difficult in Syria.[10]Only 56 percent of respondents (n = 338 of 600) volunteered information concerning their monthly household expenditures, while respondents were not asked to provide income estimates. However, even the limited self-reported data attests to the fact that to a large extent, Syrians cannot support themselves without access to aid, remittances, or coping strategies including debt or the sale of assets. Of respondents who specified a monthly spending level, 61 percent reported monthly spending at or above 201,000 SYP, roughly double the top-tier salary in the public sector — a reference point for national wages (figure 3.1). The regrettable corollary is that 39 percent of those specifying a monthly spending level spend 200,000 SYP or less, roughly 57 USD at the time of writing. Although most Syrians report that they enjoy an average standard of living, most have spending levels that place them among the poor. This is not surprising, considering that roughly 90 percent of Syrians are mired in poverty. In a sense, grinding poverty is Syria’s new normal.

Migration Nation

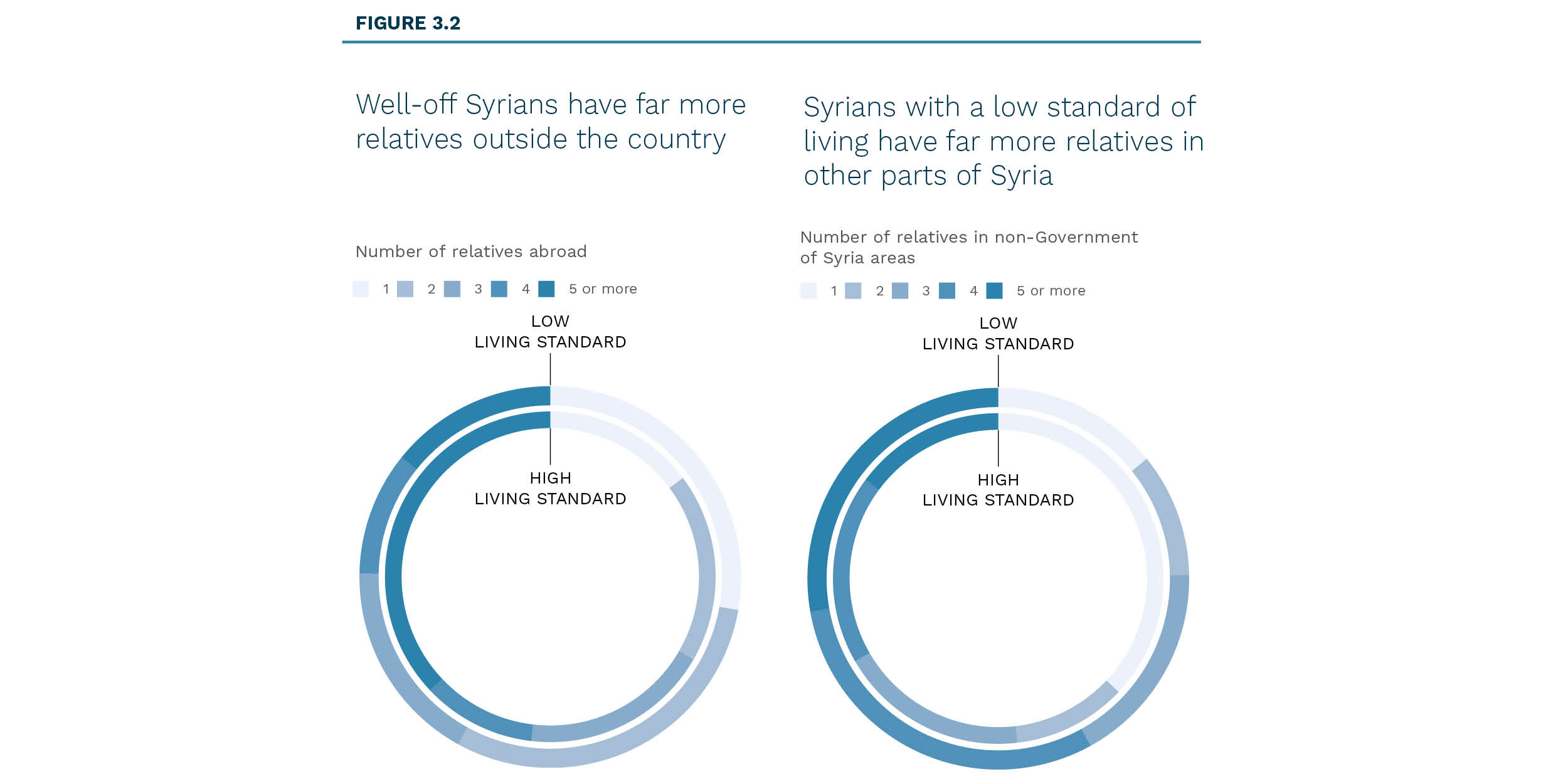

The migration of family members abroad is strongly correlated with a higher standard of living. Arguably, by 2015, the era of mass migration from Syria began to end amid tightening border policies and increasing enforcement of migration policies in Europe and neighbouring states. While flight abroad always required some degree of support, since 2017, migration from Syria has become increasingly difficult and expensive.[11]For more migration and mobility patterns, see: Karam Shaar, “Syrians on the Move,” KaramShaar.com (21 May 2020): https://www.karamshaar.com/syrians-on-the-move. The cost of the travel arrangements needed for a flight from Damascus to destinations such as Turkey or Libya now often exceeds 5,000 USD, although such conditions may be changing as regional rapprochement with the Government of Syria brings with it improved visa access regionally.[12]The Syria-Libya Conflict Nexus, COAR (2021): https://www.coar-global.org/2021/09/09/the-syria-libya-conflict-nexus/. While the data do not show when the relatives of survey respondents fled Syria, there is strong correlation between a high standard of living and the likelihood of having relatives outside Syria (figure 3.2).

Numerous factors may explain this correlation. It may be that families with high living standards have the greater financial resources, personal networks, and access to information that are needed to sustain the prohibitive costs of travel. Other factors such as education level, a proxy for income potential, may correlate with higher mobility and access to work abroad. On the other hand, it is also well understood that family members abroad are a source of foreign remittances, and Syrians who receive support from abroad generally report far greater spending.[13]In other words, remittances make up the difference between declining income and rising costs. See: Living in Damascus after a Decade of War. Simply having relatives abroad may be a key determinant of a Syrian household’s economic resilience. Of course, multiple simultaneous explanations are possible. Wealth and education facilitate migration, which in turn may open the door to more wealth and education. Crucially, because migration to other zones of control within Syria grants access to few additional high-income job opportunities, few if any benefits accrue to respondents who are separated from family members inside the country.

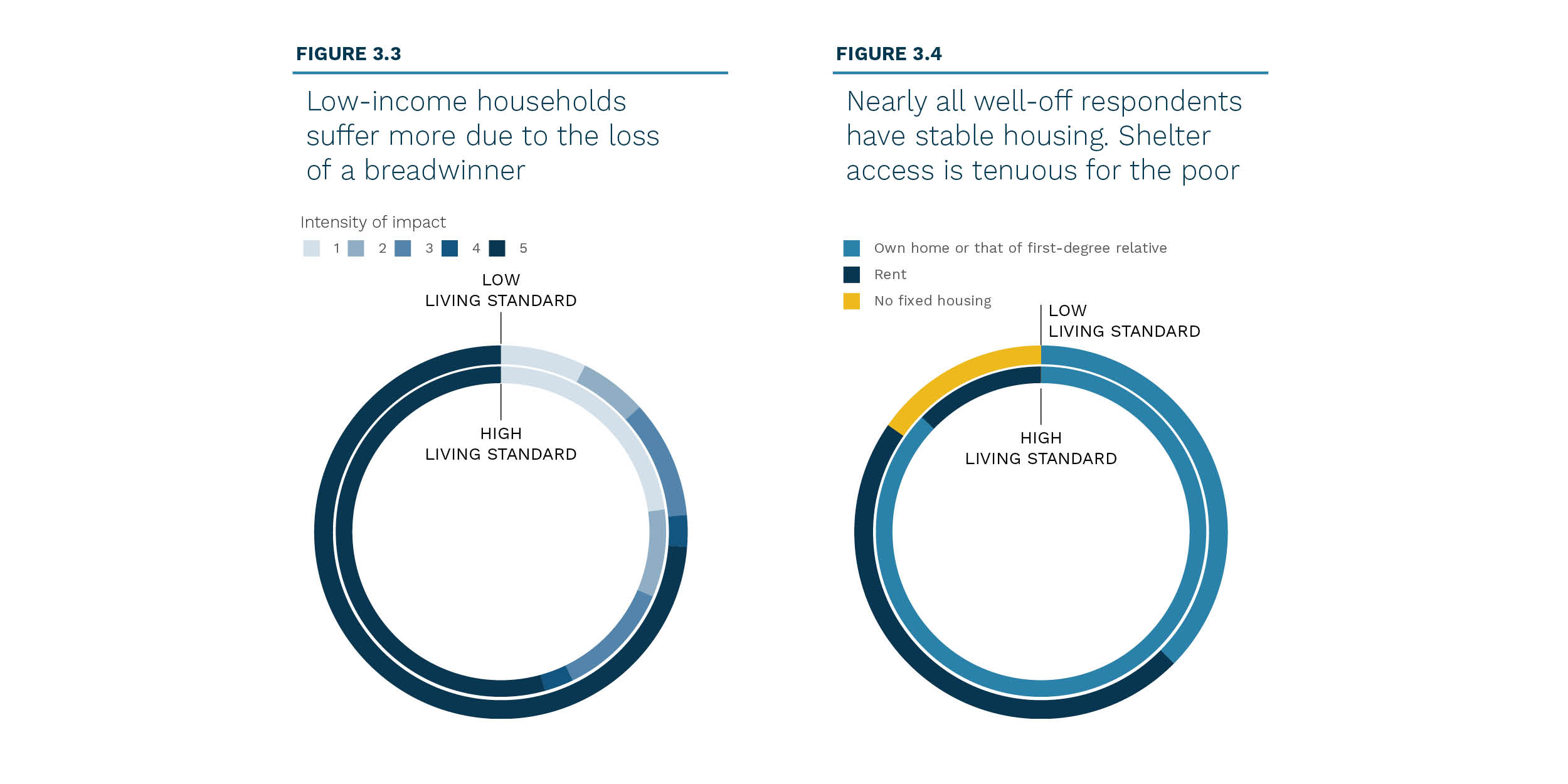

In general, the impact of separation differs greatly across economic strata. Low-income households overwhelmingly report that family separation is a major source of financial stress. However, it is important to remember how radically the conflict has altered the conditions of all households, including the formerly wealthy. Although the impact is far less pronounced than for other socioeconomic groups, even high-income respondents report that the loss of breadwinners is a major source of stress (figure 3.3).

Renters and the Rich

Quality of shelter access is strongly correlated with self-assessed standard of living. A full 87 percent of respondents who report a high standard of living reside in their own homes or the homes of first-degree relatives. This figure drops to 37 percent among those reporting a low standard of living, making it a reliable proxy for perceived household economic well-being and likely one of the key determinants of socio-economic stability (figure 3.4). This stark divide calls attention to the reality that Syrians who already face difficult economic conditions are increasingly being pushed into negative coping strategies, such as rental markets or unsafe housing conditions.

References[+]

| ↑1 | Attitudes in the Syrian Capital of Damascus: A Survey in Three Neighborhoods, Operations and Policy Center (2021): https://opc.center/attitudes-toward-emigration-in-the-syrian-capital-of-damascus-a-survey-in-three-neighborhoods/ |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Political Demographics: The Markings of the Government of Syria Reconciliation Measures in Eastern Ghouta, COAR (2018): https://www.coar-global.org/2018/12/30/2018dec13-political-demographics-the-markings-of-the-government-of-syria-reconciliation-measures-in-eastern-ghouta-coar/. |

| ↑3 | Also known as Zahirah. |

| ↑4 | For more on these communities, see: Living in Damascus After a Decade of War: Employment, Income, and Consumption, Operations and Policy Center (2021): https://opc.center/living-in-damascus-after-a-decade-of-war-employment-income-and-consumption/. |

| ↑5 | In the current case, “longing for absent family members” is used as a proxy value for mental health impacts, while the “shrinking social support network” stands in for social impacts. |

| ↑6 | LGBTQ+ Syria: Experiences, Challenges, and Priorities for the Aid Sector, COAR (2021): https://www.coar-global.org/2021/06/22/lgbtq-syria-experiences-challenges-and-priorities-for-the-aid-sector/. |

| ↑7 | The Business of Empowering Women: Insights for Development Programming in Syria, COAR (2020): https://www.coar-global.org/2020/05/15/the-business-of-empowering-women/. |

| ↑8 | Living in Damascus After a Decade of War: Employment, Income, and Consumption, Operations and Policy Center (2021): https://opc.center/living-in-damascus-after-a-decade-of-war-employment-income-and-consumption/. |

| ↑9 | Ibid. |

| ↑10 | Only 56 percent of respondents (n = 338 of 600) volunteered information concerning their monthly household expenditures, while respondents were not asked to provide income estimates. |

| ↑11 | For more migration and mobility patterns, see: Karam Shaar, “Syrians on the Move,” KaramShaar.com (21 May 2020): https://www.karamshaar.com/syrians-on-the-move. |

| ↑12 | The Syria-Libya Conflict Nexus, COAR (2021): https://www.coar-global.org/2021/09/09/the-syria-libya-conflict-nexus/. |

| ↑13 | In other words, remittances make up the difference between declining income and rising costs. See: Living in Damascus after a Decade of War. |