Syria Update Digest

On 15 February, Russian Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu made an official visit to Syria, where he met with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and inspected the Russian airbase at Hmeimim. The visit was occasioned by a string of Russian naval exercises, including in the eastern Mediterranean; a provocative show of force amid rising tension between Russia and the West over Ukraine. Moscow arguably wields more power inside Syria than any international actor, yet there are hard limits to its influence over authorities in Damascus and on the local level. Aid actors should have no illusions about Russia’s ability to bring forward political processes for a resolution to the conflict, yet should recognise how Russian presence in Syria could support in areas such as returns monitoring or logistical bottlenecks in specialist aid equipment.

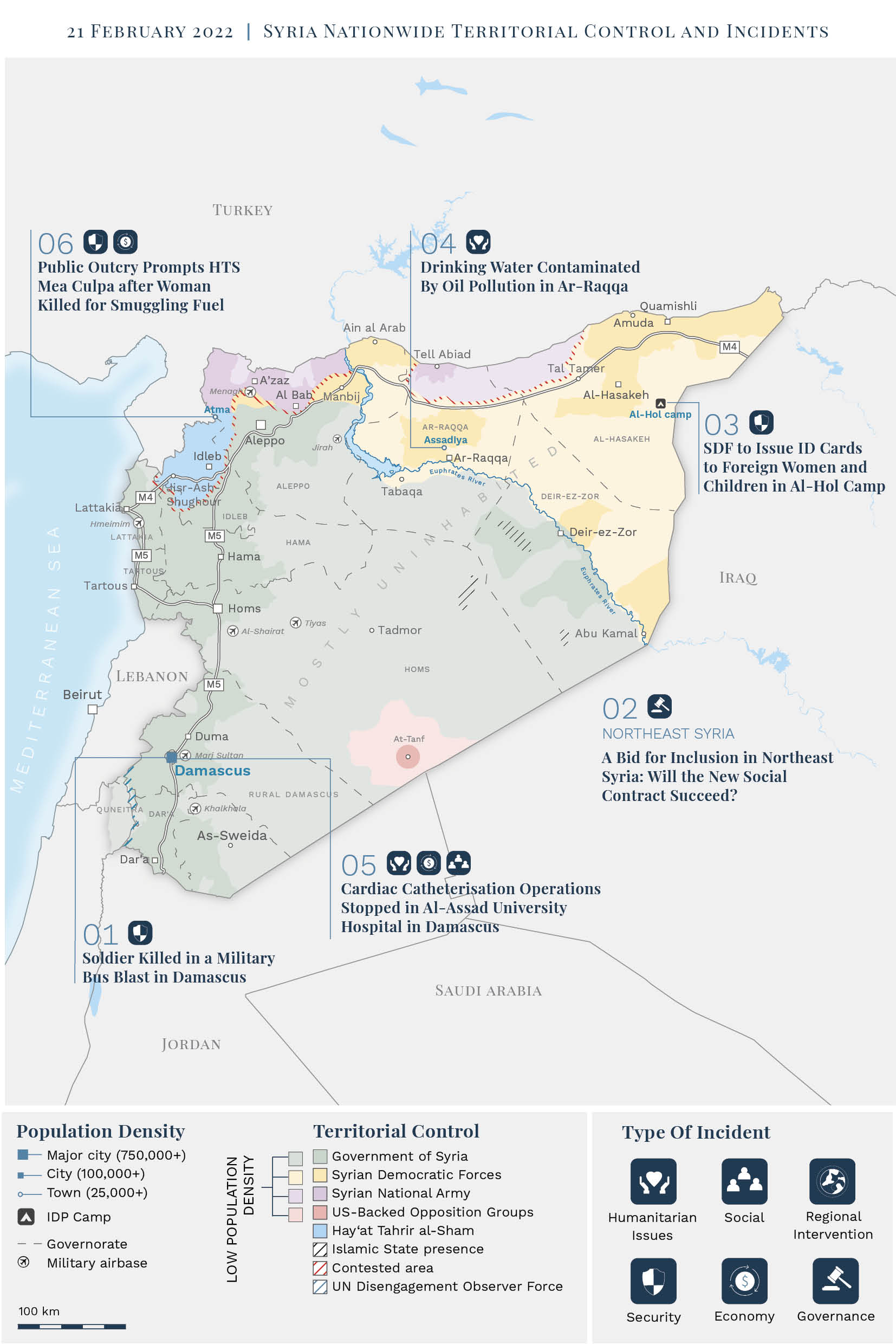

- On 15 February, the Syrian Arab News Agency (SANA) reported that one person was killed and 11 were injured when an IED exploded on a military bus carrying members of the Syrian Army near the “Customs” roundabout in Damascus, one of the capital’s most securitised areas. The explosion highlights the limits of the image of a stable Damascus pushed by the Government of Syria amid its continued calls for safe refugee return.

- On 14 February, the Autonomous Administration finalised the drafting of a ‘new social contract’ to function as a constitution ahead of planned elections across all its institutions. The contract is an attempt to address issues of inclusion and representation of Arab-majority populations and Kurdish political parties that oppose the leading Democratic Union Party (PYD). However, the Administration’s leadership remains resistant.

- On 14 February, media sources reported that the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) had started issuing identification cards for foreign women with perceived Islamic State (IS) affiliation residing in al-Hol camp. The decision could facilitate the process of repatriation; however, this can only succeed if countries are willing to accept responsibility for their citizens.

- On 14 February, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights reported complaints of drinking water polluted with diesel from leaking agricultural machinery in the village of Assadiya. Donors should be aware that the management and regulation of industrial effluent is an important component of the issue of access to water in Syria.

- Shortages of medical supplies in Government-controlled areas have caused Al-Assad University Hospital in Damascus to suspend its cardiac catheterisation operations. Shortages of medicine are an indication of the Syrian Government’s inability to provide its citizens with basic services.

- On 10 February, a woman was shot and killed by Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) while smuggling diesel into Atma, Idleb Governorate. As economic prospects in Idleb dwindle, women and children are increasingly involved in smuggling efforts, prompting protection concerns.

In-Depth Analysis

On 15 February, Russian Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu made an official visit to Syria, where he met with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and inspected the Russian airbase at Hmeimim. According to Russian state media, Shoigu and al-Assad discussed “military-technical” coordination, efforts to combat “terrorism”, and “humanitarian assistance to the Syrian population, suffering from prohibitive sanctions by the United States and Western countries”. The visit was occasioned by a string of Russian naval exercises, including in the eastern Mediterranean. The drills are a provocative show of force amid rising tensions between Russia and the West over Ukraine, where an estimated 190,000 Russian troops threaten the most significant military flare-up in Europe in decades.

Analysts, donor governments, and aid actors focusing on Syria have frequently struggled to make sense of Russian decision-making and military actions in Syria. They risk drawing the wrong lessons from the Kremlin’s recent shows of force. Moscow arguably wields more power inside Syria than any international actor, yet there are hard limits to its influence over authorities in Damascus and on the local level. Now more than ever, aid response actors must understand how Russia can exert influence in Syria — and how it cannot.

What has Russia ‘won’ in Syria?

Russia’s 2015 military intervention in support of the Government of Syria has brought it considerable benefits. It has managed to preserve a tottering client government against domestic opposition, provide invaluable combat training for its own armed forces, secure air and sea ports that enable force projection in a conflict-prone region, gain a source of battle-hardened mercenaries (see: The Syrian Economy at War: Armed Group Mobilization as Livelihood and Protection Strategy and The Syria-Libya Conflict Nexus), and open a testing ground — and advertising space — for Russian military hardware. Russia now seeks to consolidate these gains, meet its obligations to regional states including Israel, and recoup its expenses through investment or extraction.

Nevertheless, Moscow has struggled to balance regional commitments, and its economic interests in Syria remain modest. Russia has been unable to prevent Iranian proxies from seeping into reconciled opposition areas in Dar’a, despite explicit guarantees to Israel and Jordan to do so. It has also failed, or refused, to halt Israeli airstrikes. Syria’s economy remains on life support, with few trade or investment opportunities for Russian companies. Syria’s modest oil reserves remain outside of Government of Syria control, and Russia’s investment in phosphate production has proven less profitable than expected.

The failure to reach any political solution to the conflict further highlights Moscow’s limited influence over the Syrian Government, with al-Assad’s intransigence in Geneva preventing Russia from harvesting the economic and political benefits of its military intervention in Syria. Russia has rarely succeeded in pushing Damascus toward serious political compromise, prompting Moscow’s frequent signalling of dissatisfaction with the Syrian Government’s political inflexibility. According to reports from media sources allegedly close to the Kremlin, Moscow is particularly dissatisfied with al-Assad’s maximalist approach vis-à-vis the Syrian opposition and the political process and his refusal to make even small concessions as a means to end the war.

Russia is not all powerful, but remains a key stakeholder

International aid actors (in Government areas in particular) will have to account for Russia’s presence in Syria for the foreseeable future, requiring a realistic appraisal of its influence and abilities on the ground. Neither Shoigu’s visit, nor the Russian naval drills in the Eastern Mediterranean, nor other recent Russian activity in Syria fundamentally change facts on the ground for donors and implementers. For better or for worse, Russia is not omnipotent in Syria. Although aid actors and donor governments often look to Russia as a prime mover in Syria, they have seldom been satisfied. Indeed, donor governments and Russia have shared frustrations over their inability to move the Syrian Government on issues such as the Constitutional Committee and the Geneva process.

Aid actors should harbour no illusions about Russia’s ability to bring forward political processes for a resolution to the conflict. Proposals to leverage Russia’s presence on the ground to support in areas such as returns monitoring or logistical bottlenecks in specialist aid equipment have amounted to little. For the time being, political sensitivities and the legacy of rights violations endorsed or suborned by Russia will militate against such proposals. Though unreliable, Russia is a key stakeholder in Syria and so dealing with it — or around it — may prove unavoidable in the long term. For donor governments to do so realistically requires a better-calibrated understanding of Moscow’s actual capacity in the country.

Whole of Syria Review

Soldier Killed in a Military Bus Blast in Damascus

On 15 February, the Syrian Arab News Agency (SANA) reported that one person was killed and 11 were injured when an IED planted on a military bus carrying members of the Syrian Army exploded. The explosion occurred near the “Customs” roundabout in Damascus, which is among the most securitised areas in the capital. With no claims of responsibility, surmising the identity and goals of the attackers is difficult. The site of the attack, less than one kilometre from the “security square” that hosts the main security apparatuses, has pushed some to question whether the incident was a security breach, claiming instead that it was orchestrated by the Syrian Government to serve its narrative of a continuing threat of terrorism. This is unlikely, however, given the Government of Syria’s interest in projecting an image of a stable Damascus amid its continued call for safe refugee return and the normalisation of diplomatic relations.

How safe is Damascus?

This incident highlights the limits of the Syrian Government’s claims of security; however, the attack is unlikely to be a harbinger of broader violence. Attacks on military buses in highly securitised areas in Damascus are not new, though they are infrequent. In August 2021, Hurras al-Din, an Al Qaeda-affiliated group, claimed responsibility for a deadly attack on members of the elite Republican Guard in Masaken al-Haras, an area predominantly populated by Alawite members of Syria’s military and security establishment and their families (see: Syria Update 9 August 2021). In October 2021, the little-known Saraya Qasioun claimed responsibility for an IED attack targeting a Military Housing Corporation transport bus in central Damascus, killing 14 people (see: Syria Update 25 October 2021). Nevertheless, the low frequency of previous attacks and the Government’s tight security in Damascus suggest that future high-level attacks are unlikely.

A Bid for Inclusion in Northeast Syria: Will the New Social Contract Succeed?

On 14 February, the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria finalised the drafting of a new social contract, which will function as a constitution governing all territories under its control. The contract — prepared by two committees including representatives of political parties, unions and syndicates, youth organisations, and independent individuals — defines the operating guidelines of all Autonomous Administration institutions, committees, and military and security forces, and the relationship between the Autonomous Administration and its constituents. The original social contract was first announced in 2014, and did not include all territories currently controlled by the Autonomous Administration. The new version reportedly aims to “correct past mistakes” and ensure the participation of the mostly Arab populations in previously Islamic State (IS)-controlled territories. It comes amid preparations for elections spanning “all the Autonomous Administration” to begin in the next few weeks.

Inclusion, not even on paper

The contract is an attempt to stabilise governance and provide a basis for the upcoming elections by addressing issues such as inclusion and representation for the Arab-majority population as well as Kurdish political parties that oppose the leading Democratic Union Party (PYD). Other executive council officials declared that there have been “no major changes” to the contract despite the language on inclusion and representation that the document employs. While intra-Kurdish dialogue has been pushed by the US in a bid to alleviate Turkey’s concerns regarding the Kurds in Syria, parties closer to Ankara, such as the Kurdish National Council, were not represented in either of the drafting committees. Notably, the Autonomous Administration was the single most represented actor in the committees, despite concerns over bias towards the status quo and demands for the inclusion of legal experts. As the Autonomous Administration seeks to establish more state-like institutions, including a monetary authority (see: Syria Update 6 December 2021), issues of inclusion and representation of the diverse groups in the region will remain a significant concern.

SDF to Issue ID Cards to Foreign Women and Children in Al-Hol Camp

On 14 February, media sources reported that the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) has begun issuing identification cards for the thousands of foreign women with perceived IS affiliation residing in al-Hol camp in Al-Hasakeh. The process involves registering the original names and nationalities of the women and their children, as well as their sector within the camp. The ID cards will be given to the women next month after the SDF-affiliated security agency completes the necessary security checks. According to local media, these measures follow recommendations made by US forces.

A step in the right direction

Following IS’s recent attack on al-Sina’a prison, the question of repatriating those with perceived IS affiliation has become more pressing (see: Syria Update 31 January 2022 and Syria Update 14 February 2022). While the SDF has not yet offered clear reasons for the decision to issue identification cards, the move could facilitate repatriation by providing the international community with details about foreign nationals. However, the push for repatriation can only succeed if countries are willing to accept responsibility for their citizens. Donors should be aware of the continuing humanitarian needs of the women and children in al-Hol, including the approximately 85 percent of the remaining al-Hol residents who have Iraqi or Syrian nationality and who have not been included in the ID card process. Marginal, piecemeal steps such as this will be the outer limit of action on al-Hol so long as donor governments enforce red lines concerning cooperation with authorities in northeast Syria. Pressure to reassess areas of cooperation has grown since the al-Sina’a prison attack.

Drinking Water Contaminated By Oil Pollution in Ar-Raqqa

On 14 February, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights reported complaints of drinking water being polluted with diesel from leaking agricultural machinery in the village of Assadiya, which lies on the outskirts of Ar-Raqqa City. Access to clean and safe drinking water is a problem across Syria, with the head of Al-Hama municipal council recently revealing that he had monitored around 50 cases of leishmaniasis, a parasitic disease that leads to ulcers, spread through non-potable water. Syria has up to 40 percent less drinking water than it did in 2010 as a result of conflict-related destruction of water and sanitation systems, leaving many dependent on costly and often unreliable water trucking.

The true price of ‘black gold’

The management and regulation of industrial effluent is an important part of the broader issue of access to water in Syria. Oil pollution is a growing environmental and health hazard, particularly in northeast Syria, where dozens of poorly regulated, small-scale refineries have emerged in recent years, leading to leaks and contamination. However, preventing such contamination is a daunting challenge, given the lack of investment in maintenance. Effective water management and the rehabilitation of wastewater treatment facilities and other infrastructure are also sorely needed for agriculture. Agricultural production is already at an all-time low in Syria, amid drought and damaged irrigation systems (see Syria Update 10 January 2022). Notably, irrigation with untreated wastewater can introduce toxic elements that damage crops and topsoil, while livestock can be killed by drinking oil-contaminated water. With oil fields a key source of revenue for local actors, however, donors should be aware that such pollution is likely to continue as long as machinery and industrial infrastructure remains dilapidated, while waterborne parasitic disease will remain a problem so long as water treatment infrastructure remains damaged.

Cardiac Catheterisation Operations Stopped in Al-Assad University Hospital in Damascus

On 16 February, Syria TV reported that shortages in medical supplies in Government-controlled areas had caused the Al-Assad University Hospital in Damascus, one of Syria’s top health centres, to halt cardiac catheterisation operations. Al-Biruni University Hospital is also facing a 65 percent shortfall in its cancer treatment medications. The limited availability of medical supplies has triggered a staggering increase in drug prices and compelled pharmacists to ration medication handouts to customers, while hundreds of other pharmacies have closed down. The collective impact of these challenges has driven many to the black market to buy medical supplies at vastly inflated prices. The shortage of medication has also heavily impacted non-Government-controlled areas, where thousands are struggling to access medical treatment amid ongoing violence and a decrease in foreign aid.

Another sector under pressure amid economic collapse

Living conditions in Government-controlled areas continue to deteriorate with no long-term solutions in sight, with shortages of medicine serving as yet another indication of the inability of the Syrian Government to provide basic needs to its citizens. Syria is facing a health crisis compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic (see: Syrian Public Health after COVID-19: Entry Points and Lessons Learned), as patients’ needs significantly exceed the availability of affordable medications, operating health centres, and doctors. The crisis highlights the important role of non-governmental actors and aid organisations in meeting the needs of ordinary Syrians amid the difficulties faced by the public health system.

Public Outcry Prompts HTS Mea Culpa after Woman Killed for Smuggling Fuel

On 10 February, a woman was shot and killed by Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) while smuggling diesel from areas controlled by Turkish-backed factions in northern Idleb into the village of Atma, which is under HTS control. The incident sparked outrage across Syrian society. Residents of a nearby IDP camp in Atma attacked the HTS-run checkpoint at the Deir Ballout crossing in response to the incident, prompting HTS to raid and carry out arrests. Across Arabic social media, Syrians elsewhere in the country and abroad denounced HTS for its role in worsening humanitarian conditions in the northwest. On 11 February, HTS issued a statement taking responsibility for the shooting and vowing to hold the perpetrators responsible.

Watching the polls

The decision to follow up on the incident indicates HTS’s general attentiveness to public opinion, a reminder that the group is sensitive to popular pressure. However, the case also reflects the limited restraint among rank and file recruits as they interact with civilians, as well as HTS’s appetite to monopolise local economic activity. The killing is not the first case of HTS violence against civilians engaging in smuggling. Rights groups have condemned HTS for detaining children accused of smuggling in recent months. Women and children are increasingly involved in petty smuggling activities in Idleb amid diminishing educational and employment prospects, particularly for displaced people (see: Syria Update 14 February 2022). These factors, as well as HTS’s violent response, are likely to persist in the absence of economic respite or security reform, presenting specific risks for women and children. Aid actors providing protection and livelihood services in Idleb would be well-placed to coordinate a joint response to this burgeoning phenomenon. More generally, it behoves donor governments to recognise HTS’s eagerness to court public opinion, which can in some cases be used as leverage to clap back against aid interference.

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below..

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

Rebel-Held Syria Is the New Capital of Global Terrorism

What does it say? The last two IS leaders, as well as dozens of senior Al-Qaeda figures, have been killed in HTS-controlled Idleb, rendering the area the new capital of terrorism.

Reading between the lines: Driven by its goal of combating terrorist groups, the US might have an interest in developing a new regional arrangement, together with Russia, that brings Idleb under the control of the Government of Syria. Such an arrangement would, however, require a significant renegotiation of US policy towards the Assad regime.

Does Russia’s Syria Intervention Reveal Its Ukraine Strategy?

What does it say? Prior to the Russian military intervention in Syria in 2015, many US officials expected Syria to be a quagmire for Moscow. However, Russia’s military intervention was deliberately limited to prevent this.

Reading between the lines: To stand against Moscow in Ukraine, the US should understand Russia’s strategy, which does not hinge on occupying territories; rather, it employs its air force and mercenaries to limit losses and achieve goals.

SDF arrests 17 people in Deir-ez-Zor Countryside on the Pretext of Belonging to IS

What does it say? Following IS’s recent attack on al-Sina’a prison, the SDF announced the arrest of 17 men who are allegedly affiliated with IS in Deir-ez-Zor’s western countryside.

Reading between the lines: Contradictory narratives have emerged regarding the SDF’s clamp-down on Deir-ez-Zor’s western countryside. Local activists believe that the claimed IS links of those arrested are inaccurate and only serve the SDF’s narrative of fighting terrorism in northeast Syria.

Civilians killed in attack on oil company in restive north-west.

What does it say? At least four were killed and three wounded after a Government of Syria missile attack targeted a fuel tank in a major fuel market 20km west of Aleppo in opposition-controlled Idleb Province.

Reading between the lines: Despite the tenuous ceasefire that has frozen the lines of conflict in northwest Syria, shelling and bombardments are relatively common, posing a significant threat to locals and aid responders.

What does it say? The report discusses measures to operationalise humanitarian principles in the delivery of aid and avoid manipulation, instrumentalisation, and interference by the Government of Syria.

Reading between the lines: The diversion of aid to preferred beneficiaries or its siphoning and subsequent black market sale by the Government of Syria and its affiliated militias, as well as other actors, is a longstanding problem across Syria. Addressing this phenomenon will require new thinking to ensure aid reaches its intended beneficiaries and provides the foundations for peace and stability.