Basic safety is a precondition for the delivery of humanitarian and development assistance and is essential to the recovery of communities transitioning from conflict. The scale of explosive remnants of war (ERW)[1]For the purposes of this research, all types of unexploded or abandoned explosive munitions posing a threat to human life are classified as ERW. This therefore includes all types of improvised … Continue reading contamination in Ar-Raqqa is assumed to be so great however, that the city’s rehabilitation has faltered, reliance on humanitarian assistance remains high, and ordinary everyday activities remain fraught with extreme risk. Addressing ERW contamination is therefore amongst Ar-Raqqa’s most pressing needs, but mine clearance has experienced a range of paralysing practical constraints over the past 18 months and, indeed, since the first mine action missions were launched in the city following the defeat of the Islamic State (IS) in 2017.

Stabilisation actors will encounter many familiar challenges as they look to revitalise their support to mine clearance in Ar-Raqqa. It is unlikely, however, that much consideration has yet been afforded to the way in which clearance by demining agencies might interact with the city’s housing, land, and property (HLP) landscape. Typically, mine agencies look to avoid entanglement with the complexities of property rights issues that might arise because of their actions. In Ar-Raqqa, however, the longer-term moral and practical utility of doing so is questionable. First, many donor governments are implicated in the massive destruction caused primarily by Western forces under Operation Inherent Resolve. Second, fair adjudication of HLP is far from guaranteed given ambiguous local legal frameworks and a recent history of alleged property seizures, corruption, and state intervention by the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (hereafter, Autonomous Administration) and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). And third, Ar-Raqqa remains in the midst of a massive recovery and reconstruction effort at a time when its people face severe economic crisis, an uncertain future, and the legacy of some of the most brutal episodes of a ruthless war.

Following a review of the recent and present-day delivery and coordination of mine action in Ar-Raqqa, this report highlights several HLP issues that emphasise a need for heightened caution. These issues arise primarily from the limited independence of the local judiciary, alleged interference by de facto state entities, and the application of potentially discriminatory legislation, each of which present several practical and ethical post-clearance challenges. A dozen potential mitigations for the downstream effects of mine clearance on local HLP matters are provided, primarily with a view to supporting an approach that is both contextually sensitive and which reduces risk to Raqqawis, to donors and their partners, and to the sustainability of demining interventions.

1. Background

1.1. Mine and ERW Contamination in Ar-Raqqa

In 2017, it was thought that ERW contamination in Ar-Raqqa was beyond anything witnessed anywhere in the aftermath of the Second World War. Much of the threat that remains is attributed to the barbarity of the long since retreated IS. Often primitive in design and merciless in intent, IS fighters deployed IEDs throughout the city to ensure maximum possible destruction in their wake. Stories of mines wired to light switches, stashed in mattresses, and hidden in hollowed-out Qurans preserved a very real and constant sense of risk, and dozens of IED-related civilian deaths were reported in the months following the arrival of the SDF.[2]MSF (2018), Syria: Patient numbers double in northeast as more people return home to landmines. Injury and death rates may have tailed off in the period since, yet a city-wide picture of contamination is incomplete and a great many explosive devices likely remain undiscovered. Many areas are still considered unsafe, posing continued threats to life and an enduring obstacle to the resumption of ordinary and everyday activity.

Lesser reported threats have also been present in the form of explosive munitions, primarily dropped from above by International Coalition Forces (ICF) as part of Operation Inherent Resolve. According to analysis by the Carter Centre, over half of all explosive munitions deployed in Ar-Raqqa governorate were used in Ar-Raqqa city between 2013 and 2019.[3]Airstrikes accounted for 80% of all incidents of explosive munitions use in the governorate over this period, with ground-launched weapons and IEDs, landmines, and UXO detonations making up the … Continue reading With over 2,500 recorded total explosive weapons use incidents and an anticipated airstrike and artillery failure rate of between 10-30 percent, it is assumed that some 250-750 unexploded weapons must therefore be found in the city. Such assessments are at the lower end of the scale, however. Some place the number of bombs dropped on Ar-Raqqa at 20,000,[4]Guardian (2018) US air wars under Trump: Increasingly indiscriminate, increasingly opaque. suggesting the threat from unexploded ordnance may be far higher. Progress has been made to remove these weapons, but with the city labouring to recover from the effects of the international bombing campaign, a substantial legacy risk likely remains.

If reports from areas cleared elsewhere in Syria are in any way indicative of the challenges faced, it may be that clearance operations in Ar-Raqqa are measured in decades. Between 2016 and 2017, well-resourced and highly experienced Russian military engineers undertook four separate operations to clear 17,000 buildings, 1,500km of roadways, and a combined total area of 66km2 across the cities of Palmyra (Tadmor), Aleppo, and Deir-ez-Zor. The Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that these operations involved the deactivation of 105,000 explosive items, far surpassing the assumed current capacity of mine action clearance teams and their international partners in the north-east. Indeed, by way of comparison, HALO Trust and the Syrian NGO, SHAFAK, reported to the Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor that they had deactivated 317 items in Dara’a and Quneitra governorates over a four-month period in 2018.[5]Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor (2018) Syria mine action: Profile.

Box 1: Contamination and prioritisationThe rate at which Ar-Raqqa is cleared will depend on the relative balance between capacity for clearance and the scale of the problem. Though the latter is fundamentally unknown, this research has obtained information regarding the assumed distribution of contamination according to representatives from the Ar-Raqqa Civil Council. This information should not be considered as in any way approaching the results of expert survey and assessment. Rather, and as reflected by the listing of only a portion of city neighbourhoods, the distribution of contamination according to these sources is indicative only of the knowledge of individuals concerned and their anecdotal clearance priorities. UNSAFE: Local sources report the following neighbourhoods/parts of the city as currently most dangerous for civilians:

PRIORITY: Clearance priorities for those engaged by this research are based on a combined personal assessment of service access shortfalls and contamination levels i.e. they are not necessarily indicative of the most contaminated parts of the city but areas which, in their view, are most obstructive to the resumption of safe everyday activity.

|

1.2. Mine Action in Ar-Raqqa: 2017 to 2020

Shortly after IS was forced to retreat from Ar-Raqqa in October 2017, the US State Department released $230 million to stabilise ‘newly liberated’ areas in the north-east. Although funds made available for stabilisation were just one hundredth of that spent on the anti-IS campaign, a swift increase in commercial and humanitarian mine clearance nevertheless followed and hundreds of staff were hired to carry out assessments and clearance. By July 2018, U.S. officials stated that $90 million had been spent on stabilisation in north-east Syria, and that efforts to attract additional financial support for regional recovery produced a further $300 million in contributions from other coalition partners through a combination of U.S. and multilateral mechanisms.[6]U.S. Embassy in Syria (2018) Briefing on the status of Syria: Stabilisation assistance and ongoing efforts to achieve and enduring defeat of ISIS. European donors at this time included the EU, … Continue reading

In its latest official report on global U.S.-funded mine action, the State Department claims to have enabled the deactivation of over 30,000 explosive hazards across 4.5 million square metres of north-east Syria between 2013 and 2019.[7]State Department (2020) To Walk the Earth in Safety (19th edition): Documenting the United States’ commitment to conventional weapons destruction. The extent to which this work was undertaken in the immediate post-IS period in Ar-Raqqa is unclear, however. Funding from the State Department for Conventional Weapons Destruction (CWD) in FY2017 totalled $63 million, representing over 75% of all dedicated US spending on mine action in Syria since 1993.[8]Ibid, p.43. The bulk of dedicated US mine action spending has therefore occurred prior to the liberation of Ar-Raqqa in late-2017, and may have been directed primarily towards US military engineers involved in clearing roadways to support SDF military operations and/or clearing other parts of the north-east.[9]Note, CWD Syria funding shrank close to zero through FYs 2018-2020, falling well below the amount spent in Iraq over this period, and even below minor CWD spending in Jordan. This suggests some … Continue reading

With no firm commitments and only piecemeal support from other donors until the summer of 2018, it is assumed that US stabilisation money was therefore the primary resource accessed by demining agencies in Ar-Raqqa in the first nine months post-IS. Like the CWD budget however, it is not clear how much of this fund was dedicated to mine action. First, mine action is just part of a US approach to stabilisation in north-east Syria which has rested broadly on three pillars of assistance: service delivery, tribal engagement, and governance and “soft” stabilisation. The extent to which demining was prioritised across these pillars of engagement is unknown. Second, mine clearance contractors typically operate with a degree of secrecy, but this research has unearthed some inconsistencies in demining-related financial reporting which are indicative of the sometimes-erratic US policy in Syria throughout the Trump administration.[10]For instance, whereas the latest ‘To Walk the Earth in Safety’ report notes only financial contributions to the DoD under the U.S. CWD Syria programme between 2018 and 2020, USAID lists a $2.5 … Continue reading

Financial opacity aside, US funds are credited with helping to clear over 350 critical infrastructure sites in Ar-Raqqa including roadways, water stations, schools, hospitals, and sewage works. State Department reports claim that US-funded demining efforts were amongst the factors which helped reduce the number of weekly casualties in the city from over 40, in 2016, to under 4 per week in 2019. Around half a dozen Ar-Raqqa residential neighbourhoods were also declared safe for IDP and refugee returns in the first half of 2018, primarily through a combination of US-funded survey and removal via the private contractor, Tetra Tech, and capacity development support to local actors including the SDF-linked Internal Security Forces (Asayish) and the Roj Mine Control Organisation.[11]Note that Roj Mine Control Organisation was a small entity with just 30 staff and in receipt of no direct funding from the US stabilisation fund or other international donors. The group sustained … Continue reading

Though presented as evidence of ICF partner investment in Ar-Raqqa, these efforts were frequently criticised by observers who highlighted the massive disparity between the amount of destruction caused by coalition warplanes and the comparatively limited support for recovery.[12]See, for instance: Al Bawaba (2018) Why rebuilding efforts in Iraq and Syria could be doomed to fail. Progress was invariably described as too slow, and many civilians unwilling to wait for assistance took it upon themselves to remove ERW from their homes at great personal risk. Frustration with the pace of Ar-Raqqa’s recovery reached a tipping point when, in late-March 2018, the State Department suspended all stabilisation and recovery spending in Syria pending review. Naturally, concern for the future of mine action grew just months after the bulk of programming had begun,[13]Refugees International (2018) Raqqa: Avoiding another humanitarian crisis. and by August 2018, these fears were realised as the remainder of the US stabilisation grant was cancelled.

Humanitarian and commercial contractors were subsequently forced to substantially downsize their operations, with many receiving immediate stop work orders from the US Government.[14]Notably, UNOCHA reported in May 2018 that ‘mine action survey, marking, and clearance operations continue in Ar-Raqqa governorate, but not in Ar-Raqqa city’. Many of the hundreds (possibly thousands) of jobs created by the stabilisation programme vanished overnight, plunging many Raqqawi families back into economic hardship and removing the city’s most sizable source of post-IS investment. Other international funding for north-east Syria was of course available by this point, but the momentum for mine clearance had noticeably slowed and much of the demining work planned for Ar-Raqqa went unfinished. Moreover, as the ICF pushed deeper into IS-held territory into 2019, international funds for Ar-Raqqa became increasingly stretched as newly liberated communities were added to the priority list for humanitarian, development, and stabilisation assistance.

The experience of Tetra Tech is indicative of the severe interruptions most demining agencies further faced through 2019 to 2020. When stabilisation operations were at their height in the immediate post-IS period, Tetra Tech oversaw 400 personnel working across seven multi-task teams in the north-east. With the US military withdrawal announcement, the subsequent Turkish-led ‘Peace Spring’ military campaign, and the steady encroachment of Russian troops however, the company’s operations were scaled down substantially and eventually suspended altogether in October 2019.[15]Mine Action Review (2020) Syria: Clearing the Mines 2020. Work was restarted as the geopolitical picture cleared, but Tetra Tech operations were soon halted once again owing to the onset of the COVID pandemic in early 2020. The foreign expertise and equipment upon which regional mine action heavily relies was subject to fundamentally prohibitive restrictions and it was no longer deemed feasible to continue. Besides the ad-hoc emergency response work of the north-east’s political, military, and security authorities, organised mine clearance came to a near standstill. Risk awareness occupied more substantial portions of mine action budgets and no internationally-administered clearance was undertaken. It is only since summer 2021 that plans for the resumption of international support to mine clearance have resumed in earnest and resources for clearance have reportedly begun to return to the region.

BOX 2: Correlating clearance and returnSThe humanitarian community initially declined to develop a comprehensive mine clearance and support plan upon its arrival in Ar-Raqqa as it feared this might create pull factors in unsafe areas. It is unclear, however, how strongly mine clearance (or the lack thereof) correlated with rates of return in the immediate post-IS period. Regrettably, this research did not have the resources to compare the distribution of mine clearance work in the city with returns. What is clear is that around 100,000 people returned to Ar-Raqqa in the first six months following the IS withdrawal, many of whom knowingly exposed themselves to ERW. Warnings from international actors and the Ar-Raqqa Civil Council were widely ignored by residents seeking to leave displacement camps and/or recover their property, and there was near universal disregard for the city’s severe public service shortfalls given the deprivations Raqqawis had experienced during IS control and the ICF campaign. It is little surprise that untrained men desperate to earn a living offered mine inspection services to returnees unwilling to play Russian roulette with their lives, often for just 25,000 Syrian pounds per property (then around 40 euros). Recognising that returns could not be meaningfully influenced by risk awareness messaging, humanitarian actors shifted towards working in alignment with population movements but were unable to prevent a spike in ERW-related casualties.[16]Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Monitor (2021) Syria’s Landmines: Silent Killing, and; Syrian Network for Human Rights (2020) Syria is among the world’s worst countries for the number of mines … Continue reading To date, it is unknown whether an evaluation has been undertaken which might inform future efforts to better manage mass returns to heavily contaminated areas. |

2. Regional Mine Action

2.1. High Level Coordination

UNMAS serves as the lead of the Mine Action Sub-Cluster for the Whole of Syria and has active coordination hubs for Syria in Gaziantep, Amman, and Beirut. In practice, however, its mandate extends only to Syrian Government-held areas, and it partners exclusively with Government ministries and aid and demining organisations registered with Damascus. Though it is assumed to engage in some dialogue with parallel coordinating structures in the north-east through Whole of Syria platforms, no direct UNMAS support is provided cross-line and a formal UNMAS footprint is practically non-existent in the region.

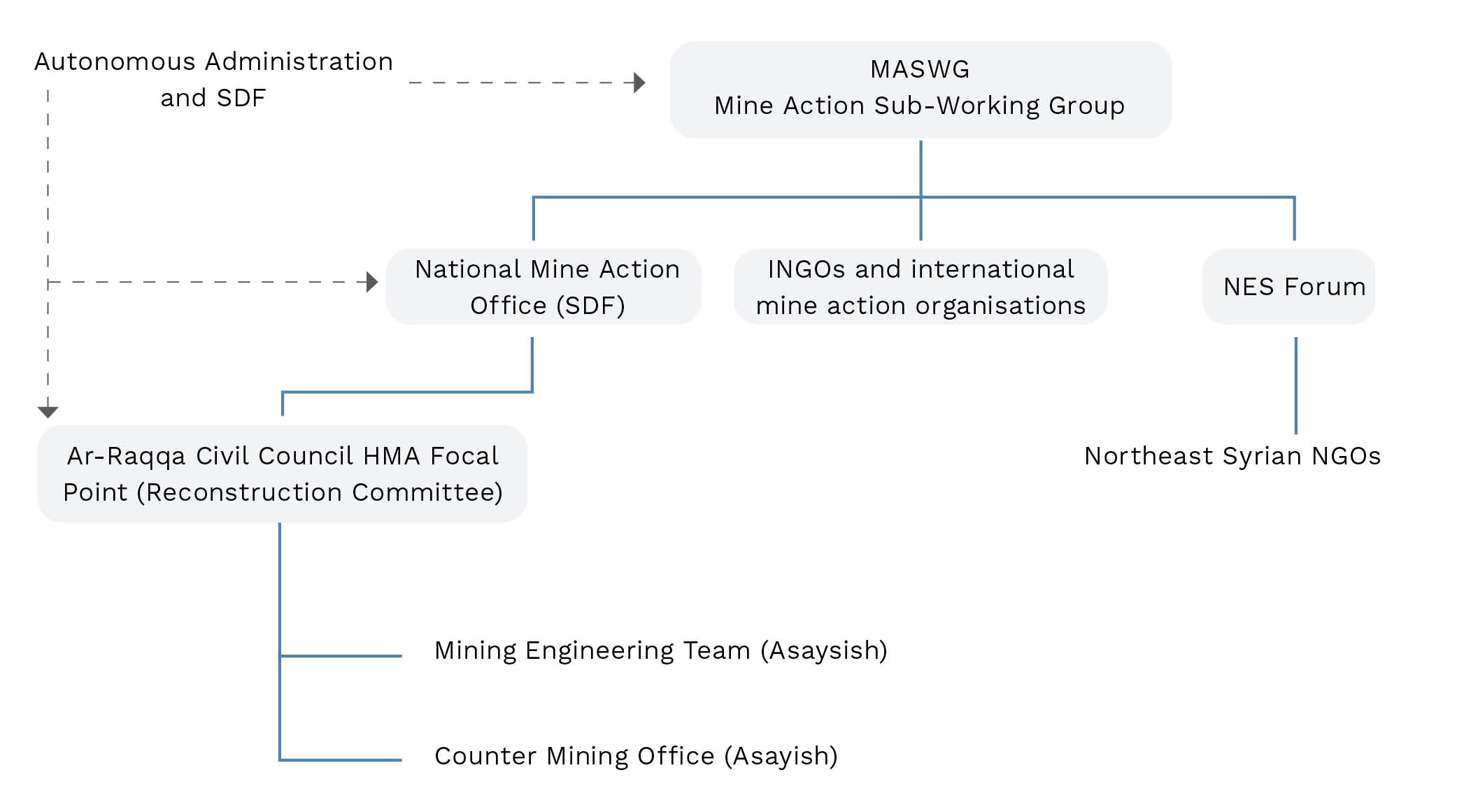

Naturally, the absence of an overarching UN coordination system has resulted in the emergence of alternative structures to absorb international mine action assistance and align work with that undertaken elsewhere in the country. At the highest level, this manifests in the form of the Mine Action Sub-Working Group (MASWG), which effectively operates as the locus of the north-east mine action ‘cluster’ and reports into Whole of Syria workstreams including the Humanitarian Response Plan, Humanitarian Needs Assessments/Overviews, and Syria-wide mine action reporting. MASWG contributions to these outputs are channelled via the Whole of Syria Mine Action Coordinator in Damascus, yet it is believed that little is shared by way of return for the same reasons that prevent UNMAS from operating outside of Government-held areas.

From its office in Amuda, Al-Hasakeh governorate, the MASWG undertakes a range of activities across the north-east, including mine action strategy development and planning, cross-sectoral coordination and collaboration, capacity building, advocacy, needs assessment, monitoring and reporting, contingency planning, and representation. It is required to promote the participation of key stakeholders across each of these activities which, besides concerned INGOs and dedicated mine action agencies, includes the North-east Syria NGO Forum and the Mine Action Office of the Autonomous Administration. Gathered under the MASWG, these parties articulate humanitarian priorities in contaminated areas, inform, monitor, and adapt the regional mine action strategy as shaped by available information sharing and analysis, and ensure that mine action is adequately integrated with the wider north-east aid response.[17]Primarily via the north-east’s Inter-Sector Working Group (ISWG).

External coordination and information management support to the MASWG and other regional mine action partners is provided by iMMAP, and is funded by the US Department of State, Office for Weapons Removal and Abatement through to 2022. Besides organising MASWG meetings, strengthening partnership with other working groups, and operating as the bridge between MASWG and the North-east Syria NGO Forum, iMMAP provides programmatic support to demining partner agencies. This programmatic support falls under broadly technical and analytical workstreams, with the former including mobile data collection, GIS products, reporting, and data visualisation, and the latter involving contamination assessment, planned clearance activities, and partner capacity mapping.

2.2. Autonomous Administration Systems and Structures

Having initially treated mine action as a predominantly military exercise concerned with the clearance of major thoroughfares and key infrastructure, the Autonomous Administration and the SDF have steadily reoriented mine action towards its more civilian dimensions and have increasingly engaged residential settings. Much of this change is embodied by the work of the National Mine Action Office (formerly, Mine Action Office), which serves as a touchpoint for the coordination of regional programming and a key MASWG partner organisation. Individuals consulted by this research stressed that regional authorities have demonstrated greater interest in the more humanitarian dimensions of mine action since the turn of the year, and that stakeholders have come to regard the National Office as an increasingly active partner. Sources at the Ar-Raqqa Civil Council add that the National Office has engaged in more frequent co-reporting alongside the Autonomous Administration’s Humanitarian Office, suggesting a growing appreciation of the extent to which mine action should be integrated with the wider orchestration of aid, recovery, and development.

Shifting mindsets within the Autonomous Administration and the SDF are at an early stage, however. Apart from limited risk awareness and victim assistance support, internationally-funded mine action in the north-east experienced a near total curtailment throughout the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic and has only recently returned to the front of the local recovery agenda. Many areas formerly under Islamic State control, including Ar-Raqqa, have therefore had just over two years to begin to address the massive levels of ERW contamination resulting from their occupation by extremists and their subsequent bombardment by coalition forces. With this initial period concerned largely with securing the city however, most clearance activities were undertaken by the Autonomous Administration’s allied military forces and focused primarily on stabilisation outcomes as opposed to those directly linked to recovery and development. Access routes, defensive positions, and military and civilian infrastructure have therefore been prioritised to a greater extent than residential and commercial neighbourhoods. For the time being, the political-military stabilisation of the SDF and the Autonomous Administration remains the presiding concern for the authorities in Ar-Raqqa, and it may therefore take some time before city officials fully engage with the breadth of mine action response options.

More proactive internal and external coordination by the National Office nevertheless bodes well for the complementarity of local and international mine action capacity. It equally promises to enhance the information available to demining agencies moving back into the region and across Syria, thereby strengthening the quality of mine action strategy and programme prioritisation. Indeed, sources report that the National Office is working in partnership with community level governance structures to develop formalised systems that are expected to support such outcomes, primarily through the creation of dedicated community focal points for mine action within local civil administrations. These focal points are reportedly tasked with assuming increasing responsibility for the coordination of mine action, including clearance supported by non-Syrian partners, and are further expected to work alongside other actors in relevant regional coordination structures. For the time being, it remains to be seen how effectively local officials perform this role in the context of the National Office’s relatively recent philosophical adjustment. Notably, they will also function as an administrative touchpoint between the primarily militarily-led elements of local demining capacity.

In Ar-Raqqa, COAR sources serving on the city’s Civil Council report the National Mine Action Office is supported by a multi-layered governance structure comprising administrative, military, and technical elements (Figure 1). The apex of the city’s local mine action structure is the Ar-Raqqa Reconstruction Committee, of which the local National Mine Action Office HMA Focal Point is a member. Ar-Raqqa’s Reconstruction Committee takes the lead on establishing priority reconstruction and community rehabilitation works, coordinating with civil society, domestic (and foreign) military actors, and other departments of the Autonomous Administration to deliver city-wide improvement works, predominantly within infrastructure and basic services. In theory, Ar-Raqqa’s Reconstruction Committee is therefore designed to support mine action in a way which sets out a timetable for public works, monitors progress and spending, and ensures the complementarity of programming on a city-wide level. To date, however, this structure is relatively untested given the recent reorganisation of local mine action coordination systems and the prolonged hiatus in regional mine clearance activities.

Under the Ar-Raqqa Civil Council sit two offices of the Ar-Raqqa Internal Security Forces unit (Asayish). It is thought that Ar-Raqqa’s Asayish are at least partially trained and funded by Operation Inherent Resolve partners, having received start up support from the mission as part of the post-IS stabilisation effort.[18]Wladimir van Wilgenburg (2017), Coalition Commander says Raqqa Police Force Paid by US as Vetted Force. The extent to which their training is sufficient to address the breadth of clearance-related activities is likely limited, however, as the primary duties of the Asayish are to manage local security and undertake counter-IS operations. That said, sources on the Ar-Raqqa Civil Council report that two Asayish offices are designated to handle local ERW issues in the city; namely, the Ar-Raqqa Mining Engineering Team, and the Ar-Raqqa branch of the Asayish’s regional Counter Mining Office. Both offices fall under the authority of Heval Ivan, Commander of the SDF in Ar-Raqqa, and respond to ERW alerts submitted to the HMA Focal Point in the Ar-Raqqa Civil Council Reconstruction Committee.

2.3. Ar-Raqqa Mine Clearance Capacity and Practice

It was not possible to gather any significant information regarding the capacity of the Ar-Raqqa Mining Engineering Team and the Counter Mining Office given the constraints of this research. It is nevertheless assumed that both entities operate with relatively basic equipment for disposal but have relatively strong experience in the identification and management of ERW risks found throughout the city. Some personnel have likely been trained to handle clearance by ICF military engineers, but much of this guidance was presumably delivered in the first months of Ar-Raqqa’s liberation and is unlikely to have been sustained. In all probability, the capacity of local demining operatives has remained largely static throughout the COVID-enforced moratorium on internationally-supported mine action and the more advanced expertise of foreign humanitarian and commercial partners remains critical to effective local clearance.

This assumption is borne out by reports from local sources that civilians continue to attempt to dispose of ERW themselves — particularly in rural areas — presumably because local actors have so far failed to demonstrate they are able to do so efficiently.[19]In 2018, for instance, when requests for demining assistance to the Civil Council were at their highest, local demining operatives were only able to attend to 1 out of every 7 cases. Ordinarily, however, new ERW alerts are reported to Asayish personnel on the street, who then feed the relevant information into local coordination structures. The HMA Focal Point may require the Asayish to coordinate with I/NGOs for more detailed survey and disposal depending on the nature of the assumed risk and its potential impact on civilian safety and city services. A dedicated hotline for reporting ERW risks direct to the National Mine Action Office was established in May 2021, but local sources claim this has been poorly publicised in Ar-Raqqa and has yet to be used as often as would be useful for its threefold purpose to receive reports and expedite response, provide risk awareness, and establish a unified data collection mechanism for regional authorities.[20]The National Mine Office hotline was announced on the SDF website, here (Arabic).

Ar-Raqqa’s mine action coordination structures are informed wholly by the reports of Asayish demining teams and, by extension, the SDF. The criteria used by these entities to determine priority locations for mine clearance is not publicly available however, and officials from the Civil Council report that they are not apprised of this information. Reports from the Asayish engineering teams are therefore relied upon by the wider mine action community somewhat blindly, effectively subsuming at least part of their decision-making power to the SDF. For international demining agencies and their donors, this should be the cause of some caution. Though represented primarily by local Arabs, the legitimacy of the SDF is questioned in Ar-Raqqa, its conduct has been the target of frequent public complaint, and it cannot be regarded as a neutral party given its overriding objective to secure the Autonomous Administration and a de facto Kurdish-dominated state.[21]For more on these assertions, see: Netjes, R. & van Veen, E. (2021) Henchman, rebel, democrat, terrorist: The YPG/PYD during the Syrian conflict. The SDF and the Asayish are perhaps amongst the … Continue reading The prospect that SDF officials may seek to promote mine clearance with a view to strengthening the political-military ambitions of the Autonomous Administration and the SDF are therefore a distinct possibility, and may undermine aspirations to promote a needs-based, transparent and accountable approach. Indeed, it is for such reasons that this paper draws attention to several areas of potential political and commercial interference that may result from demining land release.

3. DEMINING and Housing, Land, and Property

3.1. Between action and authority

Plans to resume internationally-funded mine clearance in Ar-Raqqa naturally invite questions related to HLP rights. ERW distinctly imprints post-war landscapes, and the land rights issues it presents are often multi-faceted, fluid, and contentious. Land ownership can be unclear and/or contested in areas with opaque, confusing, or exploitative tenure regimes; explosive hazard removal can trigger competition for land; and the prioritisation of certain areas can imbalance land values and usage to an extent which disadvantages residents in unsafe areas. Typically, demining agencies seek to avoid the complexity produced by these issues and seldom engage in the land disputes that result from their interventions. In Ar-Raqqa, however, they will find it difficult to remain wholly neutral on matters of land politics.

Far from recovery and with its political future in the balance, Ar-Raqqa continues to suffer the effects of massive property destruction and is subject to the contested legitimacy of the Autonomous Administration’s de facto government and its affiliated military and security authorities. Since assuming control of the city, Autonomous Administration institutions have therefore worked to stabilise both themselves and Ar-Raqqa. These twin ambitions are only sporadically aligned given the Autonomous Administration’s broader objectives in the north-east however, with military and political integrity taking precedence in practically all instances.

The most egregious consequences of this disconnect have been observed frequently across the north-east, including in Ar-Raqqa, where the Autonomous Administration and the SDF have been accused of repeat violations including property seizures, forced displacement, and unlawful demolition since 2015. Rights organisations have published numerous reports to this effect, and their observations accompany widely available testimony provided in particular by disputants resident in areas formerly under IS control.[22]See, for instance: Amnesty International (2015) Syria: ‘We had nowhere to go’ – Forced displacement and demolitions in northern Syria; Justice for Life (2018) ‘My attempts to regain my house … Continue reading Most recently in Ar-Raqqa, over 1,200 complaints were submitted to the Autonomous Administration’s Real Estate Committee regarding the seizure of property by the SDF, primarily for the use of SDF-aligned local militia fighters and their families.[23]Syrians for Truth and Justice (2020) Raqqa: The Northern Democratic Brigade arbitrarily seizes 80 houses. Where the authorities have acknowledged such complaints, they have justified their actions as concerned with combating IS’s residual threat. In most cases however, it is believed that such conduct is deployed to intimidate perceived opponents, to engineer more politically compliant communities and, ultimately, to buttress control in communities which are only partially invested in the Kurdish-dominated political project supported by the Autonomous Administration and the SDF.[24]Al-Ghazi, S. & Hamadeh, N. (2021) Policy recommendations for HLP rights violations.

Whatever the case may be, such violations highlight the often-underappreciated HLP risks that could arise from contextually insensitive mine clearance. Indeed, when the conduct of the city’s authorities is considered alongside factors such as the inconsistent application of property law in Autonomous Administration areas, repeated attempts to introduce ostensibly unethical tenure regimes, and the amount of space afforded to politically- and commercially-motivated manipulation, interference, and profiteering, the political and socio-economic consequences of internationally-funded mine clearance should be matters of foremost concern and programme planning.

3.2. Tenuous Judicial Independence and Inconsistent Property Law

In theory, the Autonomous Administration has established a clear distinction between legislative, executive, and judicial power across its several sub-regions. In practice, however, the General Council of the Autonomous Administration has not approved a full suite of alternatives to formal Syrian Law, resulting in an often-confusing picture of overlapping and conflicting legislation. Besides producing substantial inconsistency in the application of law by the Autonomous Administration’s Diwan of Justice courts, this has allowed powerful elements to influence the legal process in ways which are recognised to have affected procedural and executive decision-making. Indeed, individual litigants and parties aligned with the Autonomous Administration are reported to have influenced proceedings across a range of disputes within the north-east’s legal system, including, importantly, those relating to HLP.[25]TDA (2020) Reality of Housing, Land, and Property Rights in Syria.

In its most blatant form, this has resulted in a refusal by Autonomous Administration legal systems to act upon reasonable complaints against property seizures carried out by the SDF in Ar-Raqqa and elsewhere. Yet Autonomous Administration property law also presents more subtle opportunities to capture undue benefit from public and private property holdings. For example, Ar-Raqqa’s publicly-owned agricultural land is not overseen exclusively by the city’s Land Registry Office but is subject to the primary authority of district-level Agriculture and Irrigation Committees.[26]Similarly, state buildings, infrastructure, and associated land is managed by a Public Properties Committee. These committees are authorised to exercise considerable power over the management of, investment in, and profits from, such land and property. According to local reports, committees responsible for the management of all types of public property are “the only ones authorised to decide on public properties, large areas in Ar-Raqqa city, and the governorate in general.”[27]TDA (2020) Reality of Housing, Land, and Property Rights in Syria, p.12.

Questions should naturally arise as to the prospect that individuals sitting on such committees will look to benefit from clearance on Council-managed land, especially where they are plugged into the Autonomous Administration’s mine action coordination structure, Ar-Raqqa’s Reconstruction Committee, and/or other relevant stakeholders. Legal inconsistency and political influence are also a matter of concern in the private sphere, where bribes have reportedly been taken by officials to expedite construction work in Ar-Raqqa, and where the rulings of the courts sometimes contradict the laws set out by the Autonomous Administration.[28]Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (2021) With participation of SDF’s military and security forces, Ar-Raqqa Council demolishes 70 illegal houses and expels their owners. The prospect that released land will be subsumed by opaque property law and enable violations against private property owners cannot therefore be discounted. Indeed, this issue should be a matter of particular concern in the context of the mounting property speculation in the most damaged parts of Ar-Raqqa city.

BOX 3. Absentee Property LawIn 2015, the Autonomous Administration attempted to introduce legislation to address the use of vacant and abandoned properties. The Protection and Management of Absentee Property (Law No. 7) considered any Syrian living outside the north-east an absentee, and would have placed absentee property at the disposal of a special committee if no recognised attorney were available to represent the owner’s interests.[29]Specifically, the law required relatives TO be first- or second-degree family members and reside in Syria. Supervised by the Autonomous Administration’s Executive Council, the proposed special committee would have been empowered to invest in and/or rent absentee property and accrue the proceeds from any such use until the owner’s return. Responding to the legislation, lawyers in the region highlighted that it not only contradicted the principles of the Autonomous Administration’s founding charter,[30]Namely, that the right to property is protected for all individuals. but that it violated rights enshrined by Syrian Law which provide absentees with more freedom regarding the disposal of their assets.[31]Note the Autonomous Administration already refuses to recognise attorneys of expatriate property owners and requires an owner to attend its offices in-person to conduct their legal affairs. Public outcry over the prospect that the law might also be used to legalise property confiscation was widespread, and the Autonomous Administration was ultimately forced to abandon the plan. Despite the controversy generated by the law, the Autonomous Administration made a second attempt to introduce essentially the same legislation in 2020,[32]Enab Baladi (2020) After lots of criticism…”Autonomous Administration” suspends law of Land and Management of Absentee Property. resulting in another embarrassing withdrawal and the further erosion of public trust in its management of land and property. |

3.3. Reconstruction and Urban Planning

The scale of Ar-Raqqa’s destruction poses a significant practical obstacle to residential mine clearance.[33]In 2019, the UN estimated there were over 12,000 damaged buildings in the city, not including schools, hospitals, and other public infrastructure. Note, the Ar-Raqqa Civil Council launched a Damage … Continue reading For the people of the city however, it is an everyday burden that few have been able to wholly redress independently. Nearly four years since the end of the major conflict in the area, many property owners remain unable to cover the cost of repairs and continue to live in sub-standard, poorly serviced, and slipshod accommodation. Residents have responded variously to these circumstances: Some have taken it upon themselves to rebuild in ways which invite building code and land use violations, others continue to demand compensation, and others still have been forced to accept that they may never restore their property, sometimes selling up to speculators or abandoning their homes entirely. These behaviours have changed the city-wide property management and real estate landscape in ways which present several important practical and ethical implications for international mine clearance..

3.3.1 Land Misuse

In 2020, Ar-Raqqa Civil Council was forced to act in response to mounting informal construction on publicly-owned land. It introduced legislation that effectively deemed all prior arrangements permitting (or neglecting to prevent) private use of publicly-owned land null and void, sought to prevent further infringements upon ‘state’ property, and empowered local security forces to destroy illegal shelters and other structures as appropriate under the new legal provisions. The legislation has been applied rigorously since it was implemented, resulting most notably in the demolition of buildings in the northwest of Ar-Raqqa city, otherwise known as Hazimeh junction, in January 2021.[34]nab Baladi (2020) New decisions on state-owned property litigation in northeast Syria. The Civil Council continues to monitor construction on publicly-owned land, and particularly as this may infringe on zones earmarked for urban development.

Whether undertaken out of necessity or commercial opportunism, construction on state-owned land is an organic response to the shortage of acceptable shelter in Ar-Raqqa. One the one hand, mine action will need to ensure that it does not destabilise the delicate balance the Autonomous Administration must find between housing provision and the protection of public land. Relatedly, care will need to be taken that clearance activities do not encourage illegal and unsafe private building practices. On the other, mine action will need to be mindful of the potential for cleared public land to be misused by the Autonomous Administration and its commercial affiliates in ways that disadvantage the wider community. Besides aforementioned claims of bribery, there are rumours that an urban plan for public land in the Al-Andalus neighbourhood will benefit primarily Kurdish IDPs from Afrin. Such rumours may be off the mark, but it is vital to recall that they have surfaced precisely because Arab-majority Ar-Raqqa has struggled to adapt to the fundamentally Kurdish character of the ruling political and military authorities. Sensitivities arising from land use after mine clearance are therefore a distinct possibility and may fuel intercommunal socio-economic grievances which ultimately slow Ar-Raqqa’s recovery and the reconciliation of its people.

3.3.2 Compensation and Reparation

Internationally-funded mine clearance is likely to reopen local discussion of compensation for damages caused by government partners to the ICF, thereby generating further disquiet amongst residents with outstanding reparation demands. People who experienced total or partial damage to property in Ar-Raqqa because of the ICF bombing campaign have demanded the authorities provide compensation for their losses and remain outraged that their concerns have yet to be meaningfully addressed. Local officials insist they are working via the Engineering Evaluation Committee of the Civil Council to map city-wide damage and determine compensation for repairs. However, these efforts have not been to the satisfaction of many residents, some of whom have described the Civil Council’s compensation programme as insincere gesture politics.[35]Enab Baladi (2020) Al-Raqqa’s destroyed houses…Who compensates their owners? Rights groups have also called out ICF partner governments for “ignoring” the legacy of their actions in Ar-Raqqa, noting an ongoing refusal to offer remedy or compensation and a reluctance to acknowledge the harm caused by their assault on residents and the city fabric.[36]Amnesty International (2019) Syria: US withdrawal does not erase Coalition’s duty towards Raqqa’s devastated civilians.

Aid organisations including Mercy Corps, ACTED, and other members of the north-east’s Shelter NFI Working group have been engaged by the Civil Council to provide financial support for damaged and destroyed property based on information provided by the Engineering Evaluation Committee. Recommended amounts for repairs were determined by this Committee, and a mixture of shelter activities were undertaken by residents and/or I/NGOs with the ambition to restore damaged properties to an acceptable standard. Locals have complained that the work carried out on their homes has seldom been sufficient however, and most others have been left out of such schemes altogether.

In part, this is because price fluctuations have been so severe in recent months that longer-term shelter work has been widely postponed since mid-2020.[37]UNHCR Shelter Cluster (2020) Syria Hub: Shelter sector – Q2 2020. It may also be because the diminishing resources of residents, IDPs, and host communities has placed increased pressure on both their own limited capacities and those of shelter sector partners, thereby leading to an overall rise in shelter needs nationwide. Whatever the cause, land released by mine clearance is likely to open latent grievances as affected areas will almost certainly require investment. The return of international demining agencies starting mid-2021 may also reopen outstanding complaints. Reputational risks are therefore likely where these complaints are poorly handled and demining agencies are perceived as complicit in the failure to adequately respond to civilian demands.

3.3.3. Property Speculation

Land grabbing and property speculation is a common problem in the aftermath of mine clearance. State entities, individuals within the state bureaucracy, military officials, and powerful private actors are often attracted to the prospect that clearance will increase land values and may look to capitalise via any number of means including changes in the law, price manipulation, and coercive property purchases. There have been no known reports of this more flagrant speculation in Ar-Raqqa to date. However, there has been a worrying trend in the cut-price sale of damaged homes which owners are unable to repair and which they can no longer afford.

With Ar-Raqqa’s reconstruction ongoing, wealthy real estate brokers and building contractors have sought to capitalise on the poverty of some residents in safe areas by offering to purchase damaged property far below its real market value. In one case, an individual reportedly felt obliged to accept an offer from a building contractor for a city centre home at just 10% of its value (had the property been in good repair).[38]Enab Baladi (2021) Civilians in Raqqa selling destroyed properties under coercion. This phenomenon is a particular problem in the city’s apartment blocks, where some residents find they are unable to meet the cost of their share of repairs to the building. In such instances, poorer residents are likely under considerable pressure to sell given their inability to pay likely obstructs reconstruction and recovery for other tenants.

No legislation in Syrian or Autonomous Administration law requires an individual to sell damaged or destroyed property where their failure to carry out repairs prevents the course of reconstruction. Neither are residents under any obligation to deal with real estate brokers and construction firms in such circumstances. For many, however, the reality is that every day economic and social pressures will compel decision-making which is not in their own long-term interests and increases their vulnerability to the more predatory conduct of elites and business figures. This is likely to be a particular problem for female-headed Raqqawi households given their typically lower rates of economic and political participation.

Certainly, there is a need to rebuild Ar-Raqqa. The city’s rejuvenation cannot take place if widespread damage remains. Yet mine clearance must be aware of the potential to exacerbate forms of property speculation that fuel the disenfranchisement of poorer residents. This is especially important in the context of the Civil Council’s recent redrawing of urban development plans for several of Ar-Raqqa’s poorest neighbourhoods, most of which remain targets for mine clearance and damage repair. Announced in early July this year,[39]The press release for this announcement is available here [Arabic]. Details of the plans were not found by this research. fulfilment of these plans will be high on the agenda of municipal political and security authorities, real estate brokers, and building contractors going forward. Contingencies to support residents that may be negatively affected by these plans and the property speculation they may entail post-land release is the responsible course of action and should prompt engagement with Shelter and NFI partners.

4. Conclusions – HLP-related demining programme considerations

It is morally indefensible for internationally-funded actors to neglect responsibility for property disputes that may arise from their actions when civilians are forced to rely on institutions that they deem weak, untrustworthy, or corrupt. This report has highlighted several ways in which civilians may be exposed to HLP rights violations because of how property issues are currently managed in Autonomous Administration areas. In linking this messy legal and political landscape with land and property issues in Ar-Raqqa, it has further shown how a combination of severe destruction, sluggish recovery, and economic hardship conspire to expose residents to heightened risk arising from mine action land release.

Certainly, land issues rarely fall within the mandate of mine clearance agencies themselves. Yet such agencies are high-capacity entities working in a low-capacity environment where the effects of programming missteps can be significant both for themselves and for affected populations living in one of the most defiled cities in one the world’s poorest states. The socio-economic and political consequences of mine clearance cannot be ignored in such a context, and attention to the ways in which clearance interacts with civilian protection, reconstruction, city management, real estate, and the forces therein is strongly recommended. The following points elaborate considerations emerging from this research intended to inform the interventions of stabilisation actors with an interest in mine action in Ar-Raqqa and across the north-east.

-

- Obtain guarantees from the authorities. Property seizures are widely alleged in Ar-Raqqa. Mine clearance must not be seen to facilitate further seizures and cannot be implicated in situations where the authorities and other elites disenfranchise resident and non-resident property owners. Worrying precedents have been established in Syrian Government-held areas,[40]See, for example: Enab Baladi (2021) Residential properties in former opposition-held areas sold at auctions in Aleppo; Enab Baladi (2021) Syrians sell destroyed properties in Homs. and while the Autonomous Administration has stopped short of such measures. the prospect that owners affected by foreclosure, unaffordable damages, and their status as non-residents looms large. Given concern around the Autonomous Administration’s attempts to introduce a more proscribed absentee property law and the broader climate of legal uncertainty, there is reasonable concern that such circumstances may be used as justification for future prejudicial action.

-

- Prioritise assistance, not acreage. Low hanging fruit is attractive in a city confronted with as many developmental challenges as Ar-Raqqa. If the amount of land cleared is applied as a measure of success, demining agencies will very likely work in areas where this value is maximised. However, if the contributions of mine action to economic recovery and poverty reduction are integrated as (at least partial) measures of success, demining agencies will be encouraged to engage more critically with HLP issues.

-

- Do not neglect rural areas: It is understood that residential clearance will be prioritised as mine clearance work restarts in Ar-Raqqa. Rural areas must not be neglected however: Farmland in Ar-Raqqa’s periphery supports the north-east’s primary economic activity, and its exploitation is essential to both Ar-Raqqa’s socio-economic recovery and the restoration of the city’s status and character. Moreover, rural areas are currently underserved to such an extent that civilians are reportedly undertaking dangerous mine clearance independently to resume their livelihoods.

-

- Establish forwarding mechanisms to support compensatory support for property damages. The resumption of internationally-funded mine clearance in residential areas will renew local discussion of compensation and the role of donor governments in the ICF. Real transitional justice will require genuine acknowledgement of ICF damages. With this recognition unforthcoming, demining agencies can instead help ensure that humanitarian and development partners work to correct grievances encountered on the ground either through support to civil society documentation efforts or linking claimants with assistance.

-

- Deepen cross-sectoral coordination. Coordination structures for mine action in the north-east incorporate platforms for engagement with other sectors of assistance. Demining agencies must leverage these systems to proactively communicate their work and ensure that land release does not exacerbate HLP rights issues. For instance, shelter partners must be apprised where clearance is expected to encourage property speculation so that complementary protective initiatives are undertaken.

-

- Support civil society to monitor and document HLP issues and violations. Overriding SDF control over the determination of mine clearance priorities in Ar-Raqqa reduces opportunities for community consultation and independent decision-making by other demining stakeholders. Non-resident Syrians may have no recognised local representation whatsoever given the requirements of Autonomous Administration courts. Civil society that is empowered to monitor violations during and after clearance can play an important accountability function, add weight to people-oriented mine action, and help prevent potential resentment surrounding survey and clearance work.

-

- Provide rights-based training to local civil society. Local activists can play a complementary role to mine clearance, ensuring that communities understand their rights and hold both the authorities and aid agencies accountable for their actions. Civil society should be enabled to help residents and vulnerable groups to defend their HLP rights. They should further be empowered to undertake post-clearance monitoring processes in relation to HLP claims and disputes.

-

- Promote balanced local recruitment. Mine clearance capacity in Ar-Raqqa is managed overwhelmingly by the SDF. Many local personnel are Arab, but the organisations to which they belong are widely associated with the Kurdish-dominated authorities. Demining teams should be staffed in ways which avoid the perception that mine action is biased and/or too closely aligned with these authorities, particularly given the potential for post-clearance HLP violations.

-

- Monitor land- and property-related legislation and urban development plans. Reconstruction continues apace in Ar-Raqqa, prompting ongoing regulatory adjustment from the authorities. A failure to remain apprised of changes which affect the trajectory of the city’s reconstruction may result in preventable downstream programmatic risk.

-

- Consider the non-negotiable inclusion of land rights organisations. Matters of land rights and related liabilities for mine clearance agencies and their donors should be considered across demining activities in Ar-Raqqa, from survey through to clearance. Regional or international civil society organisations should be engaged to provide the experience, capacity, and additional mandatory power to work with land rights issues.

-

- Synchronise language with relevant stakeholders. Local sources report that stakeholders variously use different location labelling systems to describe programme locations in Ar-Raqqa. The worst potential consequences of this confusion are obvious, but more broadly they represent an everyday (and easily fixed) obstacle to mutual understanding, efficiency, and local sensitivity. The issue should be addressed across demining partners as a matter of priority.

-

- Capitalise on the opportunity to evaluate. Could more have been done to prevent ERW-related loss of life and injury as thousands of people returned to Ar-Raqqa post-Islamic State? The challenge of protecting civilians from ERW at this time was likely unprecedented and may avail important lessons. Opportunities to contribute to global mine action strategies for clearance, risk awareness, advocacy, and victim assistance in similar situations must not be lost, especially given the considerable disruption mine action has experienced in Ar-Raqqa to date.

References[+]

| ↑1 | For the purposes of this research, all types of unexploded or abandoned explosive munitions posing a threat to human life are classified as ERW. This therefore includes all types of improvised explosive devices (IEDs), landmines, shells, rockets, grenades, and weapons launched from military aircraft. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | MSF (2018), Syria: Patient numbers double in northeast as more people return home to landmines. |

| ↑3 | Airstrikes accounted for 80% of all incidents of explosive munitions use in the governorate over this period, with ground-launched weapons and IEDs, landmines, and UXO detonations making up the remaining 13% and 7% respectively. Carter Centre (2020), Explosive Munitions in Syria Report #4. |

| ↑4 | Guardian (2018) US air wars under Trump: Increasingly indiscriminate, increasingly opaque. |

| ↑5 | Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor (2018) Syria mine action: Profile. |

| ↑6 | U.S. Embassy in Syria (2018) Briefing on the status of Syria: Stabilisation assistance and ongoing efforts to achieve and enduring defeat of ISIS. European donors at this time included the EU, Germany, Denmark, Norway, Kosovo, France, the UK, Italy. Saudi Arabia reportedly offered $150 million of the $300 million total. |

| ↑7 | State Department (2020) To Walk the Earth in Safety (19th edition): Documenting the United States’ commitment to conventional weapons destruction. |

| ↑8 | Ibid, p.43. |

| ↑9 | Note, CWD Syria funding shrank close to zero through FYs 2018-2020, falling well below the amount spent in Iraq over this period, and even below minor CWD spending in Jordan. This suggests some special mine clearance allocation in 2017 that is potentially explained by ICF demining support to the SDF advance. |

| ↑10 | For instance, whereas the latest ‘To Walk the Earth in Safety’ report notes only financial contributions to the DoD under the U.S. CWD Syria programme between 2018 and 2020, USAID lists a $2.5 million State Department grant to Tetra Tech under CWD in 2018. |

| ↑11 | Note that Roj Mine Control Organisation was a small entity with just 30 staff and in receipt of no direct funding from the US stabilisation fund or other international donors. The group sustained heavy losses conducting clearance in the north-east through 2018-19 and it is unclear how active it remains in the region. |

| ↑12 | See, for instance: Al Bawaba (2018) Why rebuilding efforts in Iraq and Syria could be doomed to fail. |

| ↑13 | Refugees International (2018) Raqqa: Avoiding another humanitarian crisis. |

| ↑14 | Notably, UNOCHA reported in May 2018 that ‘mine action survey, marking, and clearance operations continue in Ar-Raqqa governorate, but not in Ar-Raqqa city’. |

| ↑15 | Mine Action Review (2020) Syria: Clearing the Mines 2020. |

| ↑16 | Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Monitor (2021) Syria’s Landmines: Silent Killing, and; Syrian Network for Human Rights (2020) Syria is among the world’s worst countries for the number of mines planted since 2011. |

| ↑17 | Primarily via the north-east’s Inter-Sector Working Group (ISWG). |

| ↑18 | Wladimir van Wilgenburg (2017), Coalition Commander says Raqqa Police Force Paid by US as Vetted Force. |

| ↑19 | In 2018, for instance, when requests for demining assistance to the Civil Council were at their highest, local demining operatives were only able to attend to 1 out of every 7 cases. |

| ↑20 | The National Mine Office hotline was announced on the SDF website, here (Arabic). |

| ↑21 | For more on these assertions, see: Netjes, R. & van Veen, E. (2021) Henchman, rebel, democrat, terrorist: The YPG/PYD during the Syrian conflict. The SDF and the Asayish are perhaps amongst the most forthright claimants of Kurdish autonomy across the various elements within the wider Kurdish political and military movement. |

| ↑22 | See, for instance: Amnesty International (2015) Syria: ‘We had nowhere to go’ – Forced displacement and demolitions in northern Syria; Justice for Life (2018) ‘My attempts to regain my house were in vain’; |

| ↑23 | Syrians for Truth and Justice (2020) Raqqa: The Northern Democratic Brigade arbitrarily seizes 80 houses. |

| ↑24 | Al-Ghazi, S. & Hamadeh, N. (2021) Policy recommendations for HLP rights violations. |

| ↑25 | TDA (2020) Reality of Housing, Land, and Property Rights in Syria. |

| ↑26 | Similarly, state buildings, infrastructure, and associated land is managed by a Public Properties Committee. |

| ↑27 | TDA (2020) Reality of Housing, Land, and Property Rights in Syria, p.12. |

| ↑28 | Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (2021) With participation of SDF’s military and security forces, Ar-Raqqa Council demolishes 70 illegal houses and expels their owners. |

| ↑29 | Specifically, the law required relatives TO be first- or second-degree family members and reside in Syria. |

| ↑30 | Namely, that the right to property is protected for all individuals. |

| ↑31 | Note the Autonomous Administration already refuses to recognise attorneys of expatriate property owners and requires an owner to attend its offices in-person to conduct their legal affairs. |

| ↑32 | Enab Baladi (2020) After lots of criticism…”Autonomous Administration” suspends law of Land and Management of Absentee Property. |

| ↑33 | In 2019, the UN estimated there were over 12,000 damaged buildings in the city, not including schools, hospitals, and other public infrastructure. Note, the Ar-Raqqa Civil Council launched a Damage Assessment and Emergency Intervention project in 2020. More recent figures may be available from the Civil Council. |

| ↑34 | nab Baladi (2020) New decisions on state-owned property litigation in northeast Syria. |

| ↑35 | Enab Baladi (2020) Al-Raqqa’s destroyed houses…Who compensates their owners? |

| ↑36 | Amnesty International (2019) Syria: US withdrawal does not erase Coalition’s duty towards Raqqa’s devastated civilians. |

| ↑37 | UNHCR Shelter Cluster (2020) Syria Hub: Shelter sector – Q2 2020. |

| ↑38 | Enab Baladi (2021) Civilians in Raqqa selling destroyed properties under coercion. |

| ↑39 | The press release for this announcement is available here [Arabic]. Details of the plans were not found by this research. |

| ↑40 | See, for example: Enab Baladi (2021) Residential properties in former opposition-held areas sold at auctions in Aleppo; Enab Baladi (2021) Syrians sell destroyed properties in Homs. |