Executive Summary

Foreigners held in northeastern Syria’s IDP camps have attracted considerable international media and political attention. Far less thought has been given to their internally displaced Syrian counterparts. Here we consider this underexplored phenomenon, discussing in particular the release and reintegration mechanisms for Syrians at two camps: Hole and Areesheh. Regional authorities have announced that they intend to disassemble the camps, but releases remain slow and ad hoc, and there are few pull factors prompting Syrian residents to leave of their own accord.

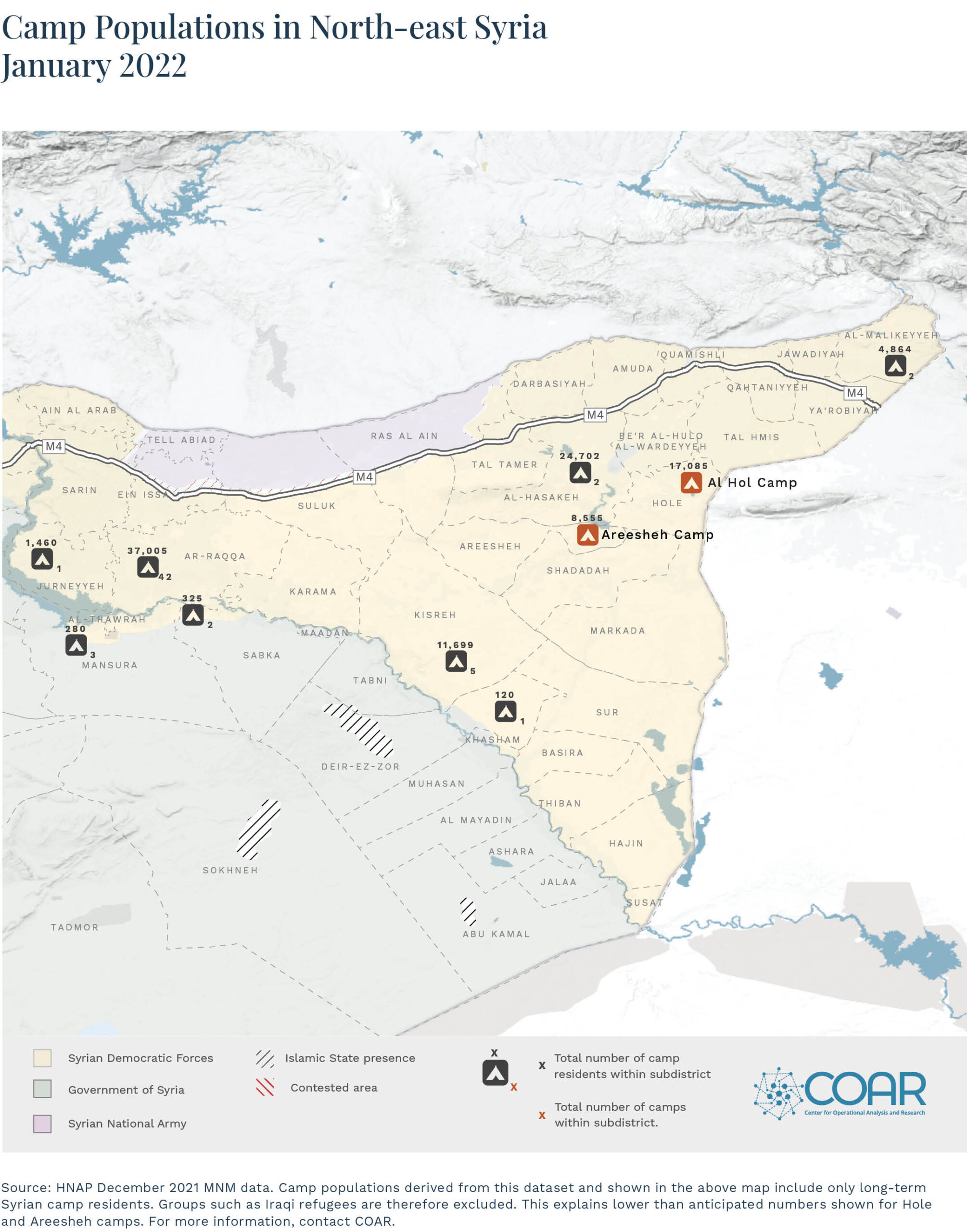

The long-term consequences of haphazard release and reintegration mechanisms for displaced Syrians are an important matter of concern for organisations invested in north-east Syria’s stabilisation. Absent a more proactive response to the challenges of regional release and reintegration, social isolation, alienation, and marginalisation will increase and alignment with extremism, the war economy, and other destabilising dynamics will become ever more difficult to dissuade. It must also be recalled that Hole and Areesheh are but two examples: Syrians in limbo at camps scattered across the north-east likely have access to even fewer resources for release and reintegration and remain even more susceptible to heightened vulnerability and radicalisation.

The Syrian Defence Forces (SDF) allows for the application of two formal release mechanisms for Syrians at Hole. Neither the tribal sponsorship nor SDF-managed release models employed there provide anything like a comprehensive solution however: both processes reportedly feature widespread corruption, are applicable only to people originating from areas under SDF control, and neither is sufficiently linked to dedicated reintegration programming. Like other smaller camps throughout the northeast, no formalised release mechanisms are currently in effect in Areesheh and reintegration options are even more incomplete. If a whole of society approach to release and reintegration is to be taken, there is an urgent need to accommodate and address the unique circumstances of Syrian camp residents. Aid programmes must also take a broader view of reintegration, targeting both returnees and host communities, and providing requisite support for economic livelihoods, psychological distress, social acceptance, and countering violent extremism.

Report findings are derived from a combination of field- and desk-based research, as well as interviews with three women who left Hole camp via the tribal sponsorship programme, four women residing in Hole, and three women residing in Areesheh.

1. Context

Thousands of people had been displaced or captured by the time the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) took control of the last Islamic State (IS) stronghold in north-east Syria (NES). With tens of thousands still in camps environments, their fate has been a subject of ongoing concern for stabilisation actors worldwide. Symbols of the international extremist threat and the shortcomings of internal security, non-Syrian camp residents have naturally attracted the majority of foreign media and political attention. Comparatively little thought has been given to the long-term prospects of Syrian IDPs and detainees, around 30,000-35,000 of whom are housed at Hole and Areesheh camps, and many thousands more at other camps scattered throughout the north-east. Local authorities struggle to manage the camps however, and questions of release and reintegration are becoming increasingly pressing matters for internal governance and security. From the international perspective, the camps present an ongoing problem for regional stabilisation objectives and the efficiency of the aid response.[1]For a detailed discussion about the history of NES, its tribal dynamics and social and local tensions between its components see “Studies for Stabilisation: Entry Points for Social Cohesion … Continue reading

1.1. Areesheh

Around 30km south of Al-Hasakeh, Areesheh camp was established by the SDF in July 2017 and is home to 14,000 people.[2]UNICEF, “Too bold to stop dreaming,” 29 July 2021. All camp residents are Syrian, the majority of whom were displaced from the Deir ez-Zor countryside, most notably from the towns of Al-Mayadin and Al-Bukamal, both of which are now under Syrian Government control. The camp is supervised by UNHCR, which provides monthly food baskets and other basic humanitarian assistance. Other organisations delivering humanitarian assistance include Save the Children, which provides periodic vouchers for pregnant women, and Blumont, which distributes daily bread rations to Areesheh and other NES IDP camps. In spite of this basic support, living conditions are reportedly dire. Most of those interviewed by COAR complained about a lack of services and support which has only worsened since the closure of the Tal Kujar Syria-Iraq border crossing with Iraq in mid-2020. Most international aid to Areesheh had previously arrived via Tal Kujar, but residents are now reliant on distributions orchestrated by the Syrian Red Crescent in Damascus.[3]For a detailed account of the humanitarian conditions in Areesheh see: Camp Profile: Areesheh, Al-Hasakeh governorate, Syria, REACH, 2020.

1.2. Hole Camp

As of October 2021, Hole camp hosts 58,965 residents and is the largest camp in NES.[4]Rudaw, “7 Syrian families return home from al-Hol camp,” 21 October 2021. Note, numbers regarding camp populations are notoriously imprecise. The estimate provided here aligns with COAR’s views … Continue reading It came under the control of the SDF in November 2015, and its population swelled massively throughout the early years of the joint SDF—US-led anti-IS coalition campaign, Operation Inherent Resolve. Families from across Deir-ez-Zor and Ar-Raqqa governorates arrived in large numbers throughout this period, with a final and substantial wave of displacement absorbed by the camp following the collapse of the final IS stronghold in Al-Baghouz in March 2019. Comprising civilians trapped by the rolling offensive, IS sympathisers and their families, this final wave contributed significantly to Hole’s Syrian population. Today, roughly one-third of the camp’s population is Syrian, half are Iraqi, and the rest other foreign nationals.[5]These figures are corroborated by the most recent Operation Inherent Resolve Lead Inspector General Report to the United States Congress for the second quarter of 2021: “As of the end of the … Continue reading Women and children account for 94 percent of the camp population. The camp is divided into nine zones: Zones 1, 2, and 3 house Iraqis; Zones 4 and 5 host Syrian IDPs; Zones 6, 7, and 8 hold the families of IS members; while Zone 9, commonly referred to as the ‘Annex’,[6]Bethan McKernan, “Inside Hole camp, the incubator for Islamic State’s resurgence,” The Guardian, 31 August 2019. holds foreigners and IS members.[7]Aaron Zelin, “Wilayat Hole, ‘Remaining’ and Incubating the Next Islamic State Generation,” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, October 2019.

The extent to which remaining camp residents are (or were) affiliated with extremism is unclear. In the larger — predominantly Syrian and Iraqi — section of the camp, overt displays of extremism are more limited than in the Annex, where the absence of effective security and camp management services allow for some continuation of IS governance and authority.[8]Anthony Loyd, “Killer IS Brides Rule Hole Camp with a Rod of Iron,” The Times, 02 October 2019. For instance, IS supporters reportedly operate religious courts to sentence “wrongdoers” who do not adhere to the “true” religion, and the interpretation of Islam is imposed by the Hisbah. [9]Riot and Chaos inside the most dangerous camp Hole,” Hewar news, 30 September 2019.

As in Areesheh, living conditions are extremely poor. A May 2020 review into conditions of the past two years concluded that “critical gaps continue to exist across all sectors, especially water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), health, nutrition, education, child protection and protection.[10]“A Children’s Crisis, Update on Al Hol camp and COVID-19 concerns,” Save the Children, May 2020. ” Diseases such as cholera, respiratory tract infections, pneumonia, and diarrhea have run riot as a result of poor sanitation and overcrowding. Shortfalls within education and protection services are further noted as serious potential catalysts of grievance and radicalisation.

The reluctance of many states to repatriate their nationals has obstructed the release and reintegration of many foreign camp residents. Foreign residents therefore confront an uncertain future until formal procedures are determined by the local authorities. In the meantime, the Syrian Democratic Council (SDC) has pressed ahead with attempts to empty Hole of Syrian residents, and particularly since an announcement to this effect on 5 October 2020.[11]Jeff Seldin, “Islamic State Families to Be Cleared from al-Hol Camp,” VOA News, 05 October 2020. The processes by which the SDC has overseen releases have been both slow and ad hoc however, and interventions to support the reintegration of former residents within host communities are lacking in number, quality, and do not appear linked to a discrete case management strategy.

Reintegration is arguably undermined by a limited understanding of the details surrounding people permitted to leave the camps via official means. As of 20 October 2021, it was believed that 19 groups of Syrians had left Hole camp.[12]Rudaw, “7 Syrian families return home from al-Hol camp,” 21 October 2021. Officials report these departures total 1,600 families,[13]ana Omer & Sirwan Kajjo, “Kurdish Authorities Release 324 Syrian Nationals From al-Hol Camp,” VOA News, 16 September 2021. while other sources point to total numbers of 12,000.[14]Wladimir van Wilgenburg, “Syria’s notorious al-Hol camp to release 69 families as part of efforts to empty facility,” 19 October 2021. Such imprecision is compounded by little in the way of knowledge around resettlement locations, onward services provided as , and other information that might support a more informed reintegration response. Ultimately, about the prospects of former residents when released back into the general population.

2. Reintegration: A Complex Process

At its heart, reintegration refers to the process by which individuals or groups who have been “outside of society” are brought back into it, and functions at the intersection of mental health, economic opportunity, social networks, and communal sentiment. As applied in humanitarian settings, it is central to the Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR) framework used by UN peacekeeping and peacebuilding initiatives worldwide. Due to the multi-layered nature of continuing conflict in Syria, no large-scale DDR programming yet exists. Nevertheless, lessons for the reintegration of Syrians within NES camps are availed by DDR best practice elsewhere.

Literature on the subject of DDR is largely focused on “ex-combatants” yet both scholars and practitioners have highlighted that the challenges associated with the reintegration of former soldiers are broadly analogous to those facing the integration of forced migrants and IDPs, including women and children. Both groups are implicated in conflict and post-conflict complexities and can operate as both perpetrators and victims of violence simultaneously.[15]R. Muggah, J. Bennett, A. Girgre, and G. Wolde “Context matters in Ethiopia: Reflections on a demobilization and reintegration programme”, in R. Muggah, ed. Security and Post-Conflict … Continue reading)

It is broadly accepted that successful reintegration rests on four pillars: economic livelihoods, psychological distress, social acceptance, and hostility.

- Economic livelihoods: Developing the capacity of individuals to support themselves (and their families) economically facilitates their ability to participate in society.[16]J. Annan, C. Blattman, D. Mazurana, and K. Carlson (2011) “Civil War, Reintegration, and Gender in Northern Uganda” Journal of Conflict Resolution 55(6): 877-908.

- Psychological distress: Exposure to violence during conflict can cause symptoms of depression and traumatic stress which demand psycho-social support. This is particularly the case for women, who are typically exposed to additional sexual violence in conflict settings.

- Social acceptance: Association with violence inflicted by armed groups can stigmatise community returnees and inhibit their social acceptance. Poverty and dependence on the community can compound these effects and demand an approach which targets both the individual and host community in question.[17]J. Hazen (2005) “Social Integration of Ex-Combatants after Civil War” p. 7.

- Hostility (CVE): Though “ex-combatants may pose a threat to peace because they are more likely to engage in violence”, hostility in the NES context is bes understood from a broader countering-violent extremism (CVE) perspective.[18]J. Annan, C. Blattman, D. Mazurana, and K. Carlson (2011) “Civil War, Reintegration, and Gender in Northern Uganda” Journal of Conflict Resolution 55(6): 877-908: p.881. Absent efforts to counter the violent IS ideology to which returnees have been exposed, both during and prior to camp residency, there is a risk that women and children will support extremism.

These four pillars are interlocking, and require a broad-based and holistic approach, as well as consideration of the safety and protection of the often-vulnerable individuals concerned. Ideally, they should be complemented by reconstruction and capacity-building efforts across healthcare, education, and localised economic development. Weak performance across these aspects of development not only inhibit reintegration at the individual level, but also community-wide. If reintegration efforts focus only on individual returnees and do not take a whole-of-society approach, they risk breeding social unrest and resentment.

3. Release and Reintegration Models

Areesheh features no dedicated release and reintegration mechanisms for Syrians but two formal approaches are in evidence at Hole camp. The first, tribal sponsorship, is a guarantor system which requires tribal representatives in communities of return provide post-release security guarantees to the SDF and ongoing pastoral support. The second involves SDF-orchestrated vetting of formal applicants and subsequent handover to municipal authorities. As described in the analysis that follows however, neither process is without its risks and inconsistencies. Questions over the protection of individuals and the community remain, and it is unclear that the stabilisation objectives of international donors are necessarily upheld by either approach.

| Box 1: Payoffs for alleged extremists

Recent reports of a third pathway to release indicate the informality of release and reintegration models currently in effect across NES. Men with alleged links to IS have reportedly been released from SDF prisons by paying $8,000-$14,000 to SDF officials to secure a ‘reconciliation deal’. Upon payment of the bribe, the arrangement stipulates that released prisoners must sign a declaration requiring that they will not rejoin an armed organisation and will leave SDF-controlled NES. Some of those claimed to have been released via this process have been interviewed by international media in Turkey.[19]Bethan McKernan and Hussam Hammoud, “Former IS fighters say they paid way out of Kurdish jail in ‘reconciliation’ scheme,” The Guardian, 22 November 2021. Their accounts have been contested, but SDF management of IS-linked captives undoubtedly requires careful attention lest such practices become so commonplace as to pose long-term problems for stabilisation. |

3.1. Tribal Sponsorship Programme

| Political | Guarantees from tribal leaders that returnees are not a security threat. |

| Economic | Little evidence of post-release economic support. Some apparent corruption, bribery, and exploitation. |

| Social | Tribal support should facilitate reintegration for both the returnees and the community. However, little evidence of programming and continued reports of community hostility. |

| Psychological | Little evidence of psychological support. |

| Safety and protection | While the tribes should offer safety and protection to women released through this model, the extent to which this is the case remains unclear, particularly for those released as a result of bribes and who do not have direct tribal connections. |

Dimensions of the Tribal Sponsorship model.

Following the Arab Tribal Forum in May 2019, leaders within the Autonomous Administration agreed to establish a tribal sponsorship programme to support the release of Syrian women and children from Hole camp. The first releases under this programme were undertaken in July 2019.[20]Maher al-Hamdan, “Tribal sponsorship system offers hope to thousands of Syrians in al-Hol camp in al-Hasakah,” Syria Direct, 26 August 2019. Those released via tribal sponsorship are required to obtain a reference from a tribal leader with knowledge of the individual concerned (and/or their family) which states the applicant does not pose a security risk. Security vetting by camp authorities is also undertaken by camp authorities. The process permits returns only to areas currently controlled by the SDF, meaning that individuals from the north-west and Government-held areas are ineligible. Individuals unable to demonstrate tribal kinship connections are similarly excluded.

Tribal sponsorship intends to generate adequate security guarantees for the SDF and a smoother reintegration process for Syrians by releasing them into the care of tribal leaders. Figures regarding the performance of the programme are few, but in October 2020, OCHA reported that 5,303 IDPs had been released via tribal sponsorship from Hole. The process has apparently been a popular option for many. As one interviewee ineligible for the programme attests, “those who have a large clan kinship left long ago”.[21]Interview conducted in Hole camp by COAR field researcher, 25 October 2021. Personal or family connections with sheikhs (wasta) were emphasised by interviewees as the main mechanism for release under the tribal sponsorship programme.[22]Interviews conducted in Hole camp by COAR field researcher, 25 October 2021.

Most remaining residents in Areesheh are ineligible for the tribal sponsorship programme given their tribal links do not correlate with areas of SDF control. Residents have voiced concern that they are unable to contact their relatives within their own tribal confederations to secure release and return. As one interviewee explained: “our relatives who live in the regime area are afraid to ask about our situation and we have not been able to reach them since we got here”. Unable to leverage the kind of connections available to their tribal peers in Hole, Areesheh’s residents are obliged to endure harsh living conditions with no formal pathway to release. Some Areesheh camp interviewees echoed this assessment, telling COAR that they saw no hope of release.

If the SDF were to permit releases to home communities in regime-held areas, applicants would be required to undergo the Syrian Government’s “status settlement” process; a procedure through which opponents of the government can reconcile their legal standing in the eyes of the state. Participation in anti-government activities must be acknowledged, and a written pledge to avoid any such future activities must be signed. Men of conscription age, defectors, and military service evaders are obliged to join the Syrian Arab Army or the Russian-managed 5th Corps.[23]For more about the “Status settlement” process see: Syria: Security clearance and status settlement for returnees, Country report, The Danish Immigration services, 2020 Evidently, such dynamics highlight additional duty of care dimensions to release which extend beyond the responsibility and jurisdiction of the SDF and its partners.

Assessment:

There are widespread reports of corruption within the tribal sponsorship system and the payment of bribes to sheikhs who then vouch for families of whom they have no knowledge. Moreover, interviewees highlighted the need for families to pay bribes and give gifts to sheikhs in order to secure the release of their relatives. In the words of one interviewee: “Nothing is for free”. Moreover, all interviewees who had left Hole camp explained that their families or tribes had done so via Rashid Abu Khawla, serving Head of the Deir ez-Zor Military Council, the foremost Arab branch of the SDF. Abu Khawla’s offices reportedly operate as go-betweens for the SDF and the region’s tribes. Interviewees were hesitant to provide details but explained that payments to tribal figures and SDF officials for mediating the release process were common.

The tribal sponsorship system is supposed to provide security assurances and an effective route to reintegration via tribal guarantees. Corruption within the process appears endemic however, pointing to weak formal oversight. The programme also appears to have been exploited to increase the incomes of well-positioned tribal figures. Moreover, and contrary to the stipulations which prohibit the release of Areesheh’s residents, individuals released via tribal sponsorship are reported to have moved to areas outside of those controlled by the SDF, including Idleb. There is also a distinct lack of reintegration programming attached to the tribal sponsorship system, with few systematic opportunities for onward work and/or education.

| Box 2: Tribe and Preferential Release

Since the SDF model was introduced, the importance of tribal sponsorship has declined significantly. The deployment of tribal status has nevertheless been used by some sheikhs in order to accelerate the release of certain individuals, often because the individual concerned is deemed to be of ‘higher priority’. The reasons for the prioritisation of certain individuals likely varies considerably, but it must be recalled that tribes are fundamentally hierarchical systems. It may be that releases are sometimes pursued for the purposes of internal tribe politics given leaders most likely expect they are ‘owed’ for their support. Similarly, tribes are a channel through which various actors can exert influence. It may be that releases are leveraged via tribes in the interests of third parties, including extremist groups. |

3.2. The SDF model – Hole

| Political | Security vetting undertaken by the SDF. |

| Economic | Little evidence of onward economic support either prior to or post-release. |

| Social | Little evidence of social or community support either prior to or post-release. |

| Psychological | Little evidence of psychological support prior to or post-release. |

| Safety and protection | No guarantees for the safety of those who return through the SDF model and some concerns over SDF treatment of applicants. |

Dimensions of the SDF release mode

In January 2021, the Autonomous Administration adopted an additional mechanism for Hole IDPs and detainees. Each week, the camp’s Civil Administration announces ‘trips’ to areas in Deir ez-Zor and Raqqa. Residents wishing to leave must register their intention to be transported to these areas pending vetting undertaken by the camp’s Civil and Security Administrations. The vetting process is undertaken along two primary channels: 1) a general security screening carried out by the Asayish, the Autonomous Administration-affiliated internal security and counter-terrorism forces (known officially as the Hêzên Antî Teror, HAT); 2) assessment of the applicant’s behaviour during their stay at the camp.

This new mechanism allows for the release of higher numbers at a faster pace than the tribal model given it involves fewer procedures and stakeholder touchpoints. It is unclear, however, how long the process typically takes either in general or for particular types of applicants. Two interviewees had applied for release two and four months ago, yet neither had received approval for an exit from Hole. Unlike tribal sponsorship, the SDF model does not require the involvement of guarantors, and neither does it establish the conditions which must be met for release. Upon approval, it is understood that returnees are handed over to municipal authorities but there is apparently no structured follow-up either in terms of vulnerability monitoring or economic, social, or psychosocial support.

Despite assurances from the Autonomous Administration that departures under the SDF model would be both safe and supported, the Asayish has reportedly prosecuted some individuals post-release. Little is known about the fate of these people and neither is there an apparent pattern to the arrests. However, such reports would correlate with others which allege the Asayish has attempted to recruit informants from SDF release cohorts, reportedly to monitor fellow returnees. Although this is only rumoured, it is clear that such reports could undermine the process and generate mistrust between released individuals and host communities.

Assessment:

With few initiatives to provide onward protection, little support for post-release livelihoods, and no clear pathways for service access, it is clear that the SDF model falls short of the kind of reintegration programming typically observed in more structured DDR processes. Many of the consequences associated with poorly planned release and reintegration are therefore more likely, including those which may undermine the broader stabilisation work of Western donors. This is no small matter. The Islamic State, for instance, remains open to those who may not necessarily believe in the organisation’s ideology but have few financial alternatives to armed group membership. Such negative coping is endemic throughout Syria and poses a considerable threat to the long-term sustainability of aid operations across the board.

In making a greater number of people eligible for the release, the SDF model has helped to reduce people smuggling from Hole. Only three reports of people smuggling have been observed over the past three months, each of which were arguably undertaken in response to the SDF tightening security. Ultimately, however, the number of people to have left the camp via smuggling is unpublished and any such informal movement is naturally difficult to track.

Individuals that fail to pass the various dimensions of the vetting process are permitted to reapply up to three times. The SDF’s intentions for those unable to clear vetting after the third attempt is unknown, however. Beyond humanitarian aid, there is similarly no plan for individuals that choose to remain in the camp of their own volition. Some women, for example, opt to remain because they lack the social and financial support outside it. Two interviewees from Hole told COAR field researchers that they would only consider leaving if they had a large family or social network and a reliable source of income in communities of return. Without this, many such people choose not to apply for release, further highlighting how reintegration programme shortcomings pose continued problems for those wishing to redistribute support from camp settings to the community.

4. Recommendations

Ending the conflict, repatriating foreign individuals, and providing transitional justice and equal opportunities for all Syrians are essential perquisites for durable IDP returns, reintegration, and community reconciliation. In the meantime, release models for NES camps must be paired with reintegration programming that is deliberate in purpose and is linked to best practice within existing DDR models. Programming should focus on providing opportunities, protection, and services in communities of return in ways which reduce the vulnerability of people to negative coping post-release, and which reduce the incentives to rely on continued humanitarian support in camp settings. Without more concerted attention to reintegration, it is likely that stabilisation objectives linked to north-east Syria’s camps will be rendered fundamentally unobtainable. The camps will remain, poor conditions will persist, vulnerability will increase, and the potential for radicalisation will rise amongst IDPs and their families.

It must also be recalled that these risks are greater outside Hole, where no real formal release and reintegration mechanisms are currently in effect and where residents present with typically different legal and social statuses. Areesheh represents one such example but is comparable to the many other less well-serviced (and well-studied) camps scattered throughout the north-east. In recognition of the distinct challenges presented by Hole compared to other camps in the region, COAR has disaggregated its recommendations accordingly.

4.1. Areesheh

Areesheh (and other comparably under-serviced) camps demand greater attention than has been afforded by international donors to date. Outside opportunities for residents are few, yet conditions within the camps are typically desperate. A lack of hope fuels grievances and makes residents more susceptible to extremism, armed group membership, and more enduring vulnerability. Indeed, COAR believes that young populations in camps like Areesheh are prime targets for extremist recruiters given the barriers to entry are far lower than Hole camp.

- The absence of clear release mechanisms for residents at Areesheh and other such locations should attract more attention from stabilisation actors. Reintegration processes structured in accordance with DDR best practice must be linked to any such processes.

- Many residents in camps like Areesheh lack legal documentation and struggle to establish contact with relatives and tribes located in Government-held areas. Dually-registered agencies with established programmes, such as NRC and the Syrian Arab Red Crescent (SARC), can help with documentation issues and facilitate contact.

- Meanwhile, humanitarian aid to Areesheh and other such camps must be sustained, and donors should further consider dedicated expansion of protection and psycho-social support programmes.

- Vocational and skill-based training is underappreciated in Areesheh, leaving residents with limited economic and social capital to increase their resilience and undertake voluntary community returns. Few capacity building activities are known to have been delivered in the camp to date.

- Little is known about the camp’s internal dynamics and the concerns of its communities. First-hand research should be undertaken to assess needs and determine appropriate programming options.

4.2. Hole

Of the two release models in effect at Hole, only one provides a limited reintegration component. Reintegration support attached to these processes must be enhanced to both increase the frequency of uptake and ensure the onward protection of people released back into the community.

- The requirements for release under the tribal sponsorship programme and the SDF model should be more clearly defined, ideally with some sort of oversight to reduce reported extortion and exploitation.

- The SDF should be encouraged to empower local and international NGOs to mediate between local communities, tribes, and the SDF. So positioned, civil society might better service reintegration needs of individuals and communities across matters of psycho-social support, training, livelihoods, acceptance, and reconciliation. The notion that disproportionate support is going to “extremist collaborators” can only be addressed by an integrated approach to individual and community needs.

- Typically identified as former (or likely) extremist collaborators or perpetrators, the needs of men and youth at Hole are underappreciated. Where there is no evidence that individuals have been involved in extremist crimes or atrocities, men and youth must feature prominently in release and reintegration support.

- Local initiatives to mediate between the SDF and camp residents who do not hail from large tribes or clans are needed. Such initiatives might provide mechanisms of release and reintegration for residents ineligible for existing models and provide a way out for residents with currently limited future prospects.

References[+]

| ↑1 | For a detailed discussion about the history of NES, its tribal dynamics and social and local tensions between its components see “Studies for Stabilisation: Entry Points for Social Cohesion Programming in Northeastern Syria”. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | UNICEF, “Too bold to stop dreaming,” 29 July 2021. |

| ↑3 | For a detailed account of the humanitarian conditions in Areesheh see: Camp Profile: Areesheh, Al-Hasakeh governorate, Syria, REACH, 2020. |

| ↑4 | Rudaw, “7 Syrian families return home from al-Hol camp,” 21 October 2021. Note, numbers regarding camp populations are notoriously imprecise. The estimate provided here aligns with COAR’s views on the likely total population. |

| ↑5 | These figures are corroborated by the most recent Operation Inherent Resolve Lead Inspector General Report to the United States Congress for the second quarter of 2021: “As of the end of the quarter, the al-Hol population had dropped to just under 60,000, of whom 51 percent are Iraqis, 34 percent are Syrians, and 15 percent are third-country nationals.” |

| ↑6 | Bethan McKernan, “Inside Hole camp, the incubator for Islamic State’s resurgence,” The Guardian, 31 August 2019. |

| ↑7 | Aaron Zelin, “Wilayat Hole, ‘Remaining’ and Incubating the Next Islamic State Generation,” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, October 2019. |

| ↑8 | Anthony Loyd, “Killer IS Brides Rule Hole Camp with a Rod of Iron,” The Times, 02 October 2019. |

| ↑9 | Riot and Chaos inside the most dangerous camp Hole,” Hewar news, 30 September 2019. |

| ↑10 | “A Children’s Crisis, Update on Al Hol camp and COVID-19 concerns,” Save the Children, May 2020. |

| ↑11 | Jeff Seldin, “Islamic State Families to Be Cleared from al-Hol Camp,” VOA News, 05 October 2020. |

| ↑12 | Rudaw, “7 Syrian families return home from al-Hol camp,” 21 October 2021. |

| ↑13 | ana Omer & Sirwan Kajjo, “Kurdish Authorities Release 324 Syrian Nationals From al-Hol Camp,” VOA News, 16 September 2021. |

| ↑14 | Wladimir van Wilgenburg, “Syria’s notorious al-Hol camp to release 69 families as part of efforts to empty facility,” 19 October 2021. |

| ↑15 | R. Muggah, J. Bennett, A. Girgre, and G. Wolde “Context matters in Ethiopia: Reflections on a demobilization and reintegration programme”, in R. Muggah, ed. Security and Post-Conflict Reconstruction: Dealing with fighters in the aftermath of war. London: Routledge (pp. 199-200 |

| ↑16 | J. Annan, C. Blattman, D. Mazurana, and K. Carlson (2011) “Civil War, Reintegration, and Gender in Northern Uganda” Journal of Conflict Resolution 55(6): 877-908. |

| ↑17 | J. Hazen (2005) “Social Integration of Ex-Combatants after Civil War” p. 7. |

| ↑18 | J. Annan, C. Blattman, D. Mazurana, and K. Carlson (2011) “Civil War, Reintegration, and Gender in Northern Uganda” Journal of Conflict Resolution 55(6): 877-908: p.881. |

| ↑19 | Bethan McKernan and Hussam Hammoud, “Former IS fighters say they paid way out of Kurdish jail in ‘reconciliation’ scheme,” The Guardian, 22 November 2021. |

| ↑20 | Maher al-Hamdan, “Tribal sponsorship system offers hope to thousands of Syrians in al-Hol camp in al-Hasakah,” Syria Direct, 26 August 2019. |

| ↑21 | Interview conducted in Hole camp by COAR field researcher, 25 October 2021. |

| ↑22 | Interviews conducted in Hole camp by COAR field researcher, 25 October 2021. |

| ↑23 | For more about the “Status settlement” process see: Syria: Security clearance and status settlement for returnees, Country report, The Danish Immigration services, 2020 |