Syria Update Digest

On 15-16 June, the 18th round of the ‘Astana’ talks took place in Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan, with delegations from the three so-called guarantor states, Russia, Turkey, and Iran; the Government of Syria; and the opposition. The talks yielded no substantive progress. Once a dynamic format where deals could be made between the guarantor states that have the greatest military stake inside Syria, the Astana format has produced diminishing returns, in part because the military dynamics with which the talks were so deeply intertwined have also slowed in consequence of Syria’s largely ‘frozen’ conflict. With aid actors able to do little to affect the outcome of these political processes, they should recognise that significant movement and resolutions are unlikely in the near term and thus should look to improve modalities of humanitarian and recovery interventions under the current political framework.

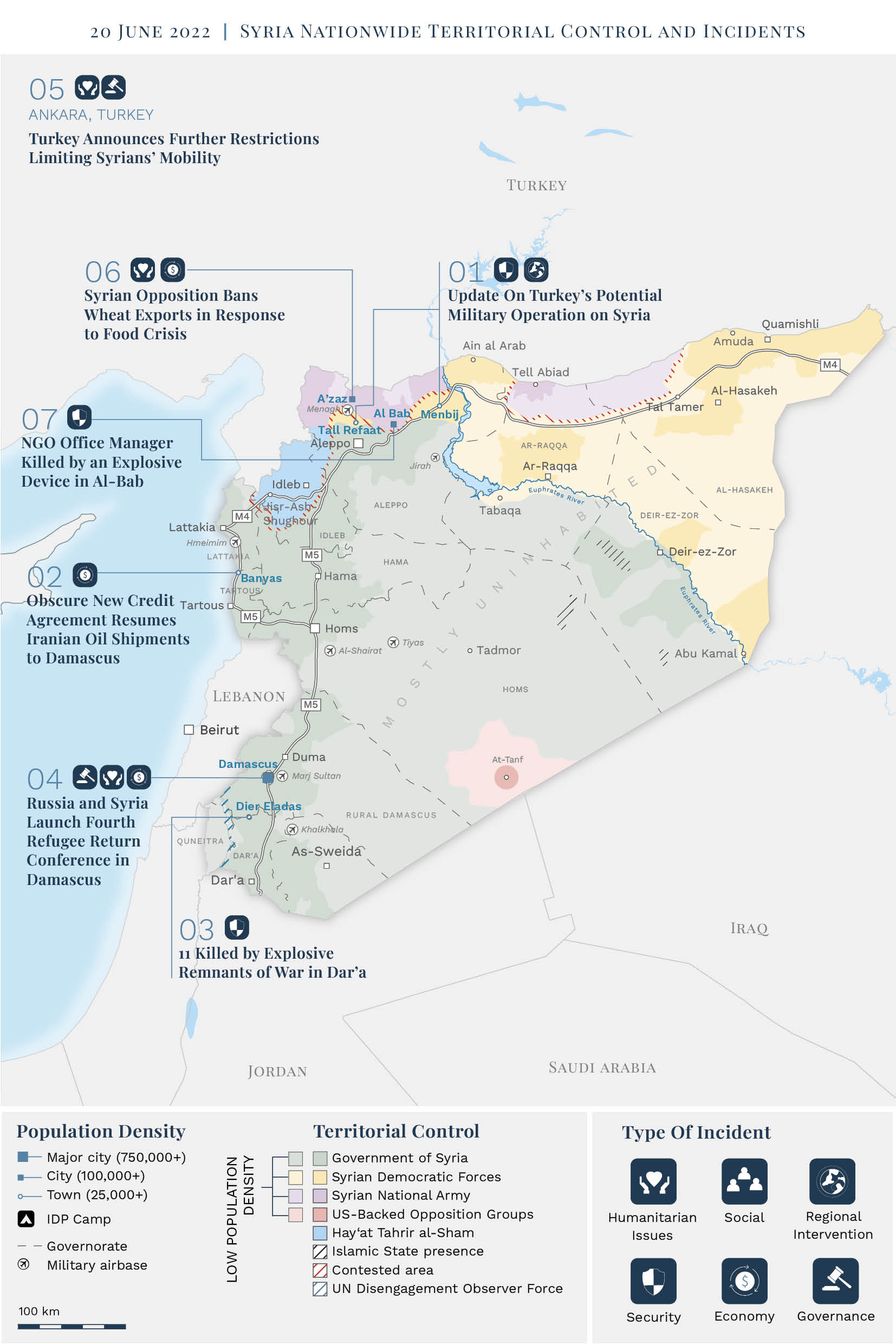

- This is the second weekly update on Turkey’s potential military operation in northern Syria (see: Syria Update 13 June 2022). No major changes have been reported on military deployments in northern Syria, while international actors including the US and Russia have maintained their opposition to Turkey’s military plan.

- On 13 June, Iranian oil tankers delivered two million barrels of crude oil to the Banyas refinery on the Syrian coast. The relief is welcome, as a delay in Iranian crude oil shipments has caused notable shortages across Government-held territories, highlighting Damascus’ deep dependency on Tehran.

- 11 people were killed in Dar’a on 12 June when a flatbed truck carrying dozens of civilian farmworkers struck an explosive device. The incident highlights the ongoing threat of explosive remnants of war (ERW) for Syrians, especially in Government-controlled areas, where clearance efforts have been insufficient and options for aid sector response limited.

- On 14 June, the fourth Syrian-Russian meeting of the International Conference on the Return of Syrian Refugees and Displaced Persons took place in Damascus. The events are a stalking horse for reconstruction support, as the Government of Syria remains incapable of and unwilling to welcome refugees back.

- On 12 June, Turkish Interior Minister, Suleyman Soylu, announced a new set of policies which will limit the movement of foreigners — including Syrians — residing in Turkey. Donor agencies should note the resulting protection risks and the decisions’ potential impacts on future migration flows.

- The Syrian Opposition Interim Government recently banned the export of wheat and other strategic crops from its territory. The ban is a signal of the seriousness with which the Interim Government is taking the food crisis, with food insecurity reaching high levels throughout Syria.

- On 15 June, the Office Manager of the Humanitarian Relief Association (IYD) in Al-Bab city was killed by an explosive device that was planted in his car. Civilians, including humanitarian workers, continue to bear the brunt of the insecurity in areas controlled by the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA) in northern Aleppo.

In-Depth Analysis

On 15-16 June, the 18th round of ‘Astana’ talks took place in Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan, with delegations from the three so-called guarantor states, Russia, Turkey, and Iran; the Government of Syria; and the opposition. The Astana format is conventionally considered as parallel to the Geneva peace process and its associated Constitutional Committee process, which recently concluded its eighth round of talks with no discernible progress (see: Syria Update 6 June 2022). In contrast with Geneva, the Astana talks were once a dynamic format, where Syria’s most influential foreign military actors could respond to, and ultimately shape, large-scale military activities in the country, albeit without the capacity to hasten a necessary political solution.[1]Astana’s chief late-life outcome was a de-escalation framework that temporarily reduced violence around opposition enclaves such as northern rural Homs, eastern Ghouta, and Idleb. Arguably, the … Continue reading However, the conflict has slowed, and the modest outcomes of recent meetings in Nur-Sultan suggest that the talks are largely exhausted, offering little apart from a regular forum for sideline discussion among the concerned powers. The international community has few alternatives, particularly as attempts to build confidence between Syria’s warring parties and the international community falter. With aid actors able to do little to affect the outcome of these processes, they should recognise that breakthroughs are unlikely in the near-term and thus look to improve modalities of humanitarian and recovery interventions under the current political framework.

Little talk, little action

In the run-up to the meeting, Kazakhstan’s foreign ministry highlighted that the talks would focus on refugee return, an issue that has attracted growing attention amid growing pressure in major host states in recent months.. However, the joint statement issued by the guarantor states following the meetings offered no novel steps on refugees and indeed contained few changes from those issued previously. Most notably, the statement “condemned the actions of countries that support terrorist entities including illegitimate self-rule initiatives in the North-East of Syria” and “rejected… discriminatory measures through waivers for certain regions which could lead to this country’s disintegration by assisting separatist agendas,” a reference to the recent US sanctions waiver for northern Syria, which Turkey in particular views as a potential boost to its Kurdish foes on the ground (see: Syria Update 13 May 2022). As with earlier meetings in the Astana format, the event was preceded by a small-scale prisoner swap between the Turkish-backed opposition and the Government of Syria, trumpeted by the guarantor states as a success of their “Working Group on the Release of Detainees / Abductees, Handover of Bodies and Identification of Missing Persons.”

The modest outcomes highlight the divergence among Astana guarantors, as do their contradictory public stances following the meetings. In the context of Turkey’s threatened incursion in northern Syria (see: Syria Update 30 May 2022), Turkey’s foreign ministry used the event to emphasise Syria’s territorial unity (a reference to northeast Syria’s semi-independent trajectory) and reiterated its willingness to launch a new offensive in the country. Meanwhile, Russia’s ministry of foreign affairs vocalised its opposition to such an operation, stating that it would not contribute to Syria’s stability or security. However, Russian and Syrian state media emphasised their agreement on action against terrorist groups, namely Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) in Idleb Governorate, a local force that currently provides a buffer between Syrian Government forces and Turkish territory. Iran, which has often been sidelined during Astana negotiations, condemned the US presence in northeast Syria and called for the end of sanctions, while also emphasising that it and Russia share “common views” regarding Syria.

Between Astana and Geneva — Abu Dhabi and Muscat?

Perhaps seeking to deflect from the slowdown in Astana talks, following the sessions, Russia’s Presidential Envoy to Syria Alexander Lavrentyev proposed moving the Syrian Constitutional Committee meetings from Geneva to “a more neutral platform” in the Gulf, because of what he described as Switzerland’s “unfriendly, and even hostile” position towards Russia resulting from its invasion of Ukraine. This point was also reflected in the joint statement following Astana, which “underlined the necessity that the Constitutional Committee should conduct its activities without any bureaucratic and logistical hindrances.” The UN Special Envoy’s office has already rejected the proposal, which threatens to further disrupt or delay what little progress towards political resolution to Syria’s intractable military, political, and displacement crises can be made.

Although the suggestion to abandon Geneva as the site of Constitutional Committee talks highlights the need for new approaches to break the deadlock and achieve sustainable progress for Syria, it would be wrong to view the problem as being rooted in venue. Among other things, the talks are flawed because they fail to meaningfully represent key stakeholders, including authorities from northeast Syria. Nonetheless, there is also doubt over confidence-building measures. The UN Special Envoy Geir Pedersen’s “step-for-step” approach, a process intended to build confidence amid stalled negotiations between the Government of Syria and interlocutors on all levels, has been rejected as a nonstarter by key opposition figures (see: Syria Update 28 March 2022). Progress via step-for-step is likely to be slow and require coordination between sometimes disunited actors, as seen in a recent test case. Although Pedersen had hoped to realise Syria’s recent ‘terrorism’ amnesty (see: Syria Update 9 May 2022) as such a step, Western actors disavowed the move as lacking coordinated steps in response, or clarity on remaining detainees and access for independent monitoring. Sequencing and coordination issues such as these will impede future confidence-building measures which, although slow and difficult, are seemingly the next best hope for change in Syria’s political dynamics.

Whole of Syria Review

Update On Turkey’s Potential Military Operation on Syria

This is the second weekly update on Turkey’s potential military operation in northern Syria (see: Syria Update 13 June 2022). So far, no major changes have been reported on the military deployments of actors in northern Syria, while international actors including the US and Russia have maintained their opposition to Turkey’s military plan.

- Russia doubles down on opposition. On 15 June, Russia’s Syria envoy Alexander Lavrentyev stated that Moscow “considers Turkey’s possible military operation in Syria unwise as it could escalate and destabilise the situation.” Lavrentyev also confirmed that Moscow would not consent to a Turkish operation in exchange for Turkey blocking the NATO membership of Finland and Sweden. On 16 June, Lavrentyev told reporters that Moscow had attempted to persuade Ankara to cancel its military plan and find a peaceful solution to the issue.

- Ankara biding its time. On 13 June, Hurriyet, a Turkish newspaper close to the ruling party, reported that Turkey will launch its military operation in Syria after Eid al-Adha on 12 July. Hurriyet attributed the delay to Ankara’s desire to end its operation in northern Iraq against the PKK, known as “The Claw-Lock”. Additionally, it has been reported that the Syrian National Army (SNA) has formed an operation room in preparation for taking part in Turkey’s operation.

- The US maintains a red light. Although US officials have not publicly discussed the issue in the past week, on 16 June, Ilham Ahmad, the co-president of the Executive Council of the Autonomous Administration, stated that US diplomats continue to reject any Turkish operation in Syria, confirming Washington’s known stance in regard to the operation.

Obscure New Credit Agreement Resumes Iranian Oil Shipments to Damascus

On 13 June, two Iranian oil tankers delivered two million barrels of crude oil to the Banyas refinery on the Syrian coast. This was reportedly the first shipment delivered as part of an updated credit line agreement between the two countries, facilitated during Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s unannounced visit to Iran in May (see: Syria Update 16 May 2022). First signed in 2013, the credit agreement between the two countries allows Damascus to finance imports of essential goods and commodities, including fuel. In April 2021, Syrian Prime Minister, Hussein Arnous, stated that Syria needs 200,000 barrels of crude oil per day (bpd) to meet its domestic needs (approximately six million barrels monthly), of which only 20,000 bpd are produced within Government-held territories. The remainder must be imported, mainly from Iran or territories in northeastern Syria controlled by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces, which is then refined for local consumption.

Iranian oil is back, for now

The delay in Iranian crude oil shipments has caused notable shortages across Government-held territories, highlighting Damascus’ deep dependency on Tehran. It also highlights the latter’s likely desire to secure more favourable conditions to this costly alliance. Despite some degree of recent regional rapprochement with Damascus, few material benefits of these discussions have yet emerged (see: Syria Update 21 March 2022). Tehran’s long-standing economic support to Damascus has also become increasingly unreliable as it struggles to deal with an economic crisis of its own. While beneficial to Damascus, this rapprochement may have encouraged Tehran to secure more favourable terms for its continued credit line. The details of the new agreement were not publicised, however. Syria is facing acute fuel challenges, and shortages prompted restricted fuel allocations to governorates, forcing the temporary suspension of fuel supplies to public transport in Damascus Governorate earlier this month. The resumption of the Iranian credit agreement will alleviate such pressure. However, until the conditions of the new agreement are revealed, its sustainability remains doubtful, particularly as Damascus bears the weight of an accumulating — albeit unspecified — debt to Tehran.

11 Killed by Explosive Remnants of War in Dar’a

On 11 June, 11 civilians were killed in Dar’a governorate when the flatbed truck they had been riding on — which was carrying at least 35 people, primarily agricultural workers — struck an explosive device (reportedly a landmine). The blast, which occurred near the village of Deir Eladas, wounded as many as 34 others, some seriously; three women and five children were among the deceased. It is unclear who planted the device, which was likely left over from fighting prior to the Government of Syria’s recapture of the area in 2018. According to Euro-Med, the victims are the latest of over 65 Syrians killed by explosive remnants of war (ERW) throughout the country since the beginning of the year.

The grim legacy of a decade of war

ERW contamination is and will continue to be a major threat to civilians throughout Syria (see Syria Update 14 February 2022 and Demining in Ar-Raqqa). This is especially true in areas re-captured by the Government of Syria, such as southern Syria, where aid sector access is limited. While information about mine clearance activities is difficult to ascertain given the opacity of the industry, no credible international mine action actor is known to have conducted any clearance in Government of Syria-controlled areas aside from limited efforts by UNMAS. While Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA) signed an MOU with the Syrian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Expatriates in December 2021 for the establishment of a programme, it is unclear whether any clearance has actually occurred. There is no evidence that systematic humanitarian clearance has been conducted by Russian forces or the Syrian Government, which have limited capacity in this field. As a specialised and high-risk skill set, building capacity for ERW clearance is a challenge for implementers. Approaches that minimise the need to deal directly with the sanctioned Government of Syria, such as remote dissemination of risk education materials to civilians, are likely to remain among the only options for aid actors seeking to reduce ERW-related injuries and fatalities in southern Syria. Until consistent access without Government of Syria interference is a reality for humanitarian mine clearance actors, ERW clearance in southern Syria is unlikely to be complete and civilians will continue to be victims.

Russia and Syria Launch Fourth Refugee Return Conference in Damascus

On 14 June, the fourth Syrian-Russian meeting of the International Conference on the Return of Syrian Refugees and Displaced Persons took place in Damascus. During the conference, funded by Russia, the Syrian Government emphasised refugee return as one of its main priorities and sought to paint a picture of Syria as safe and ready to receive returnees, as it has done on previous occasions (see: Syria Update 2 November 2020). The event showcased Russia’s interest in investing in both development and humanitarian endeavours in Syria, and was followed by signed agreements concerning increasing economic and political cooperation.

Rebuild it and they will come?

Although the conference advertises Syria’s purported interest in refugee return, in reality, the country is both incapable of providing services and administration to large numbers of returnees and likely unwilling to accept them, politically. Indeed, al-Assad has publicly welcomed at least one outcome of the war: a ‘homogeneous Syrian society’ consisting of loyalists. The Government of Syria’s fundamental military strategy until 2018 pivoted around efforts to divide the Syrian population between opposition fighters and sympathisers — who were displaced abroad or forcibly relocated to rebel-held enclaves in the north as a result of reconciliation agreements — and loyalists and unproblematic populations (see: Political Demographics: The Markings of the Government of Syria Reconciliation Measures in Eastern Ghouta).

As such, ongoing initiatives to facilitate refugee return are driven by the desire to secure political and monetary support for reconstruction efforts by tapping into international fatigue concerning Syria in general and refugees in particular. The EU and other Western actors maintain, correctly, that Syria is not safe for return, a reality underscored by many Syrians’ decision to remain in increasingly hostile host countries despite worsening conditions (see: Syria Update 13 June 2022). According to the Humanitarian Needs Assessment Programme, just under 2,500 individuals returned to Syria from abroad between January and May 2022 — with the most important reason for return cited as the need to protect assets or properties. Nonetheless, there is a temptation among many actors involved in the Syria crisis to use refugee politics and the weight of host country burdens to flip the script, and insist that safe return can be guaranteed when Syria has been rebuilt. It is important for the donor community to recognise that reconstruction support of the type the Government of Syria and Russia are seeking will not alter the underlying realities that make Syria unsafe for return.

Turkey Announces Further Restrictions Limiting Syrians’ Mobility

On 12 June, the Turkish Interior Minister, Suleyman Soylu, announced a new set of rules for migrants in Turkey, many directly relevant to Syrians residing in the country. Among them: A) Syrians who travel to Syria for the Eid al-Adha holiday will be barred from returning to Turkey, B) no more than 20 percent of residents of Turkish districts can be foreign nationals, and C) Syrians hailing from Damascus will not be able to receive temporary protection status in Turkey and will instead be returned directly to Syria upon arrival. This follows the Turkish government’s plans to “ease” the return of Syrians to a “safe zone” in its areas of control in Syria’s north (see: Syria Update 3 May 2022).

In lieu of durable solutions

The announcements continue the trend of increasingly stark measures against foreign residents in Turkey amid anti-immigrant (and notably anti-Syrian) sentiments, which coincide with the run-up to the 2023 elections. The announcement concerning Damascus residents likewise highlights the precedent set by Denmark’s 2021 decision to declare Damascus safe for return, despite conditions throughout Syria continuing to present risks (see: Point of No Return? Recommendations for Asylum and Refugee Issues Between Denmark and Damascus). Such policies appear to have a snowball effect in Turkey and are unlikely to abate ahead of the 2023 presidency elections. They will likely further encourage migrants in Turkey to embark west or return to Syria amid new incidents of violence against Syrians in Turkey in recent weeks (see: Syria Update 13 June 2022). Aid actors must be prepared for the livelihood and protection challenges that will face Syrians who stay in host communities or decide in the face of pressure to risk unsafe return.

Syrian Opposition Bans Wheat Exports in Response to Food Crisis

On 19 May, the opposition Syrian Interim Government banned the export of wheat and other strategic crops from its territory due to the growing global food supply crisis, seeking to compel farmers to sell to local merchants. The Interim Government has yet to announce its purchase price for wheat this year, though last month the Government of Syria set its price at 2,100 SYP per kg (approximately 0.52 USD at black market rates), followed by the northeast Syria’s Autonomous Administration, which upped the price to 2,200 SYP per kg (approximately 0.55 USD). Competition over wheat prices usually erupts between the various authorities each year as they look to secure crops from the upcoming harvest. Despite bans on cross-lines sales, smuggling to areas with higher profits continues to pose a problem.

Hunger likely to continue

The ban on wheat exports is a stark signal of the seriousness with which the Interim Government is taking the food crisis. With international wheat prices still high due to the supply shock following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (see: Syria Update 7 March 2022), the Interim Government can likely ill afford to replace its own limited wheat production with imports. The increased price of agricultural inputs, including fuel and fertiliser, has reportedly led farmers to reduce the land under cultivation this year, suggesting another poor harvest year to follow last year’s drought (see: Syria Update 10 January 2022). The success of the ban on exports is contingent on the wheat purchase price set by the Syrian Interim Government; if it is lower than that of the Government of Syria or the Autonomous Administration, then it is likely that outward smuggling will continue, putting further pressure on food security in the region. Food supply in Syria remains of serious concern; aid actors should be aware of the risk of hunger and famine should the harvest season proceed poorly, as nearly 60 percent of Syria’s population (12.4 million people) are already food insecure.

NGO Office Manager Killed by an Explosive Device in Al-Bab

On 15 June, the Office Manager of the Humanitarian Relief Association (IYD) in Al-Bab city, Amer Al-Fen, was killed by an explosive device that was planted in his car. The explosion took place outside Al-Fen’s house in Al-Bab city centre, also injuring several pedestrians and causing material damage. In response, the Syria Response Coordination Group condemned bombings that target civilians and humanitarian staff, stressing that this is not the first such incident, nor do they expect it to be the last due to the “continuous recklessness [of security forces and controlling parties]”. IYD is a Turkish-registered humanitarian organisation that was founded in 2013 and oversees programmes in Turkey and northwest Syria. According to an IYD staff member, it is unknown who targeted Al-Fen, but fingers usually point to the SDF or IS when such incidents occur. The victim had no known enemies and had no prior involvement with armed groups.

Aid challenges near Syria’s frontlines

Civilians, including humanitarian workers, continue to bear the brunt of the insecurity and chaos in the areas controlled by the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA) in northern Aleppo. The region is exposed to security incidents including bombings, assassinations, and IEDs, in addition to infighting between factions. Since the beginning of the year, the area has witnessed a number of explosions, and the SNA has announced several thwarted attacks. Syria is at the top of the list of the deadliest places to be a humanitarian worker. Maintaining and increasing humanitarian services and access is paramount, integral to which is ensuring that humanitarian workers can perform their duties without the fear of being harassed, arrested, or targeted with violence. The recent incident reminds aid actors of the need to prioritise the protection of humanitarian workers and the importance of establishing greater clarity around core duty of care standards, with policies that correspond to the risks their staff are exposed to and technical and financial support from donors.

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below..

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

Non-Governmental Organisations in Aleppo: Under Regime Control and at its Service

What does it say? More than five years after the fall of Aleppo to Government forces, the Government of Syria maintains dominance over the activities of local NGOs there by intervening at four levels: foundational (e.g. granting or obstructing licencing), structural (e.g. determining board composition), functional (e.g. intervening to promote or stonewall partnerships and projects), and resource (e.g. seizing funding or in-kind aid).

Reading between the lines: The four levels of intervention identified in this paper can be a useful guide for aid sector actors (both donors and implementers) as they evaluate risk and establish risk management approaches, both in Aleppo and elsewhere.

Three Scenarios for the Impact of the War in Ukraine on Syria

What does it say? There are three scenarios for the war in Ukraine in the next six months – namely, a peace deal (unlikely), prolonged conflict (most likely), or an expansion of the conflict (somewhat likely), each of which will have different consequences for Syria.

Reading between the lines: The prediction is sound, and its implications of the likely long-term continuation of the Ukraine conflict — that Syria will likely see little movement in the security or political domains, but serious economic deterioration — are ones aid actors in Syria should incorporate in their planning.

Syria Economic Monitor, Spring 2022 : Lost Generation of Syrians

What does it say? Suffering from 12 years of conflict and economic crisis over which its economic activity was halved, Syria faces high inflation and a likely 2.6 percent contraction in real GDP in 2022, with attendant negative impacts for welfare, especially among the more economically vulnerable.

Reading between the lines: As forecasted in COAR’s Syria in 2022 paper, the primary drivers of humanitarian need in Syria no longer derive from military action and violence, but from deprivation and economic crisis — compounded by the ongoing pandemic and the knock-on effects of the war in Ukraine.

What does it say? Government security services in southern Syria have franchised the work of suppressing dissent out to an array of competing gangs, many of which are involved in feuds, drug trafficking, criminal activities, and family disputes.

Reading between the lines: As the Syria Update 6 June 2022 describes (from the perspective of the drug trade), the security landscape of southern Syria is extremely complex, with a multiplicity of actors and interlocking drivers of conflict, resulting in high levels of violence and instability and posing serious challenges for any aid actors that might seek to work there.

What does it say? The damage to the airport caused by the 10 June Israeli strike forced interruption of humanitarian aid; the UN calls on all actors to respect international humanitarian law.

Reading between the lines: Whether the Israeli strike deliberately targeted airport infrastructure is unclear, but may signal an escalation in Israel’s air campaign against Iranian assets in Syria which could negatively impact aid flows.

References[+]

| ↑1 | Astana’s chief late-life outcome was a de-escalation framework that temporarily reduced violence around opposition enclaves such as northern rural Homs, eastern Ghouta, and Idleb. Arguably, the agreements hammered out via the format reduced violence in the short term but ultimately contributed to the armed opposition’s intractable fragmentation and provided a framework for the Government of Syria, Russia, and Iran to isolate and eliminate pockets of opposition. |

|---|