Introduction

On 12 January 2022, the head of Syria’s Planning and International Cooperation Commission, signed a memorandum of understanding with the Chinese ambassador to formally bring Syria into the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China’s 1 trillion USD instrument for strategic development in Eurasia and Africa.[1]SANA (2022), “Syria, China sign MoU in framework of Silk Road Economic Belt Initiative,” available at: https://sana.sy/en/?p=260411 and OECD (2018), “China’s Belt and Road Initiative in … Continue reading Syria’s accession to the BRI fuels speculation over China’s future ambitions for the country. Among analysts, some view Syria’s inclusion in the BRI as a guarantee of eventual Chinese investment to safeguard its regional interests. Others conclude that the Chinese leadership’s historical aversion to geopolitical risk will indefinitely delay, or altogether thwart, meaningful engagement in Syria, a country that remains deeply unstable.

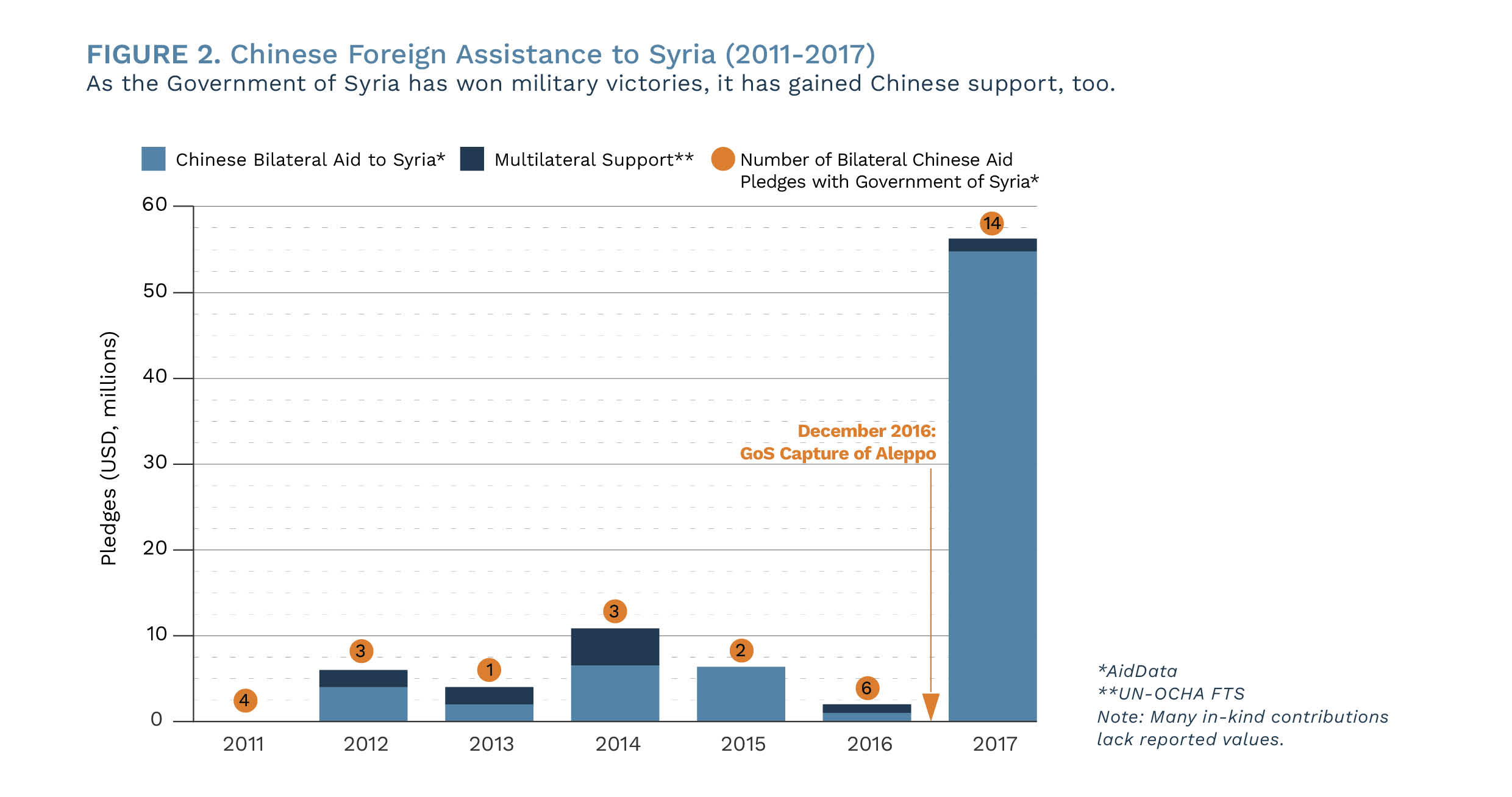

Although such uncertainty is understandable, there are concrete indicators that shed light on China’s evolving strategic engagement with wartime Syria. Humanitarian assistance, for example, presents a case study in Beijing’s increasingly focused engagement with the Government of Syria. Arguably, such assistance — including multilateral pledges and little-assessed bilateral commitments, including technical grants and in-kind aid[2]While it is possible to debate the nature of this assistance, an overly rigid or narrow definition is arguably unhelpful. Indeed, Western aid funding is often described using the shorthand … Continue reading — presents the most comprehensive data set available for understanding the evolution of Chinese political relations with Syria, allowing for year-over-year comparisons across different phases of the conflict.

A definitive evaluation of China’s vision for its long-term role in Syria is not yet possible, but elements of its approach began to surface in 2017 or earlier. This shift coincided with the Government of Syria’s capture of Aleppo city in December 2016, arguably a decisive turning point in the conflict that restored state control over the country’s traditional economic hub. Crucially, in the period that followed, Chinese humanitarian aid has been reconfigured in a manner that is emblematic of a broader policy shift that has brought Beijing and Damascus into closer alignment. This shift reversed course after multiple years in which China’s rhetorical and diplomatic support for Damascus were, like its humanitarian assistance, measured and often tokenistic. Analysis of these trends points to a two-part approach to Chinese strategic engagement in Syria. First, its humanitarian support has been funnelled directly to a seemingly secure Government of Syria, conveying valuable political support when Damascus has secured few stable international partnerships. Second, the ties prompted by this support are seemingly calibrated to pave the way for future private-sector investment, particularly in manufacturing, which Damascus has courted as a catalyst for broader economic recovery.

Naturally, on-the-ground realities, sanctions, and latent political risk will complicate investment in Syria by state actors or private firms for the foreseeable future. However, the frameworks for engagement that have already taken shape seemingly dispel uncertainty over China’s willingness to play an economic role in post-conflict Syria, although precisely how such involvement will take place is a matter that will be shaped by externalities, including sanctions and other elements of geopolitical risk. Ultimately, important questions concerning the BRI’s role as a vehicle for significant investment in Syria by the Chinese state, for instance to guarantee access to the Lebanese port of Tripoli, remain unanswered.

Key Findings

- Chinese humanitarian assistance is a key indicator of Beijing’s shifting engagement with Syria. In this respect, the fall of Aleppo (December 2016) marked a turning point in China’s aid strategy, prompting a 100-times year-over-year increase in aid (from roughly 500,000 USD in 2016 to 54 million in 2017), an apparent sign of greater confidence in the Government of Syria’s staying power.

- Chinese assistance has often been overlooked because it has largely been delivered outside UN aid frameworks. Since 2017, China has channelled most of its support, largely in the form of economic and technical cooperation agreements and COVID-related supplies and vaccines, directly to the Government of Syria as it has ramped up efforts to build stronger political and economic ties with Damascus. Nonetheless, its overall commitments are modest compared with those of other donor governments.

- Although China has yet to articulate a clear agenda for Syrian reconstruction or the BRI in Syria, a hybrid approach is taking shape in the light of the ‘post-Aleppo’ aid model. Beijing has since pledged up to 2bn USD in support for industrial parks, while its long-term approach — a model promoted by Bashar al-Assad — seemingly favours eventual private-sector and manufacturing investment to rejuvenate Syria’s flagging economy.

- To date, private-sector investment has been stymied by physical, financial, and legal insecurity and sanctions. Al-Assad has encouraged Chinese firms to evade restrictive measures, to little apparent success.

Recommendations

- While aid politicisation is an ever-present risk in Syria, Chinese humanitarian assistance appears unique in this respect, as it has been overtly fashioned to achieve political impact by currying favour with Syrian authorities. Western donors should take steps to clarify and communicate the objectives of their own assistance in Syria, particularly given that beneficiaries are seldom able to distinguish among donors and may not recognise a distinction between the objectives of Chinese assistance and those of other aid actors.

- Western donors should develop clear communication strategies to disseminate information concerning the scale, scope, and purpose of their assistance, particularly on social media. This is vital if they are to correct the information asymmetry, for instance in areas such as COVID-19 assistance, where Syrian state media has exaggerated the support of China and downplayed the contributions of other donors and the COVAX facility.

- Donor governments focused on creating the conditions for a sustained, market-based economic recovery in Syria should closely monitor Chinese private investment, particularly in manufacturing or industry, which may in some cases buoy their own efforts to support Syrian livelihoods and economic resilience.

- The potential models of Chinese reconstruction support in Syria give little cause to anticipate an emphasis on vital humanitarian needs and services, and instead are likely to focus on private-sector return and the means of cementing geostrategic interests. While it is possible that the Chinese state could someday endorse humanitarian reconstruction efforts, there is as yet little indication that it is prepared to do so. While Western donor governments should be wary of the co-optation of any rehabilitation or reconstruction agenda, in the long term it may be necessary to identify points of complementarity with other actors operating on the ground in order to maximise the benefits to the Syrian people.

Part I: Aid As a Bellwether of Chinese Attitudes toward Syria

The impediments to delivering humanitarian assistance in Syria make the context one of the most challenging and complex humanitarian responses in recent memory. Among the multitude of issues complicating the aid response is the Government of Syria’s ultimate responsibility for the majority of civilian deaths in the conflict, while Government forces and their allies are implicated in numerous reported rights violations, including the use of chemical weapons and torture. For legal, reputational, and strategic reasons, these factors have complicated the task confronting donor governments, which must in some fashion work through the central authorities to reach the roughly two-thirds of Syrians who live in Government-controlled territories.[3]This issue is explored in-depth in Carsten Weiland’s Syria and the Neutrality Trap: The Dilemmas of Delivering Humanitarian Aid through Violent Regimes. With few exceptions,[4]It is noted that some major donors choose to operate expressly in accordance with the wishes of the Government of Syria, which they view as the sovereign legal authority in the country. This view is … Continue reading major donor governments therefore seek to minimise their exposure to Syrian authorities as they grapple with the hard realities of delivering aid to people in need. Indeed, donor governments generally hold that key milestones in Syria’s future trajectory such as reconstruction, refugee return, and political normalisation with the Syrian Government are impossible until the political reforms couched under UN Security Resolution 2254 are implemented.

Surveying the same conditions in Syria, China has taken the opposite approach. Seemingly unencumbered by such considerations, Beijing has wielded its modest aid to strengthen political bonds with the Government of Syria. Based on public data, it can be estimated that China has contributed more than 100 million USD in humanitarian assistance to Syria since the outbreak of the conflict in 2011, in addition to tens of millions in in-kind support to battle the COVID-19 pandemic and an estimated 80 million USD to support neighbouring states dealing with fallout from the conflict.[5]These estimates are based on public commitments announced by the Chinese state, Government of Syria, or both. Critically, a lack of transparency impedes independent verification, and many commitments … Continue reading Thus, Chinese humanitarian support is monetarily insignificant when compared with the contributions of Western donors, yet when assessed longitudinally, humanitarian assistance is a little-noticed bellwether of China’s willingness to put increasing weight behind Damascus. Four distinct phases of Chinese aid engagement with Syria are evident, each corresponding with a major phase in the trajectory of the conflict.

Phase 1: State Media Blitz (2011). The first — brief — phase in Chinese aid to wartime Syria[6]It can be disputed at what point the uprising in Syria evolved into a conflict. For the purposes of this paper, “wartime Syria” encompasses the popular demonstrations that marked the beginning of … Continue reading consisted of a series of in-kind donations to strengthen state media capacity in early 2011, as the Government of Syria sought to quell a nascent popular uprising demanding political and economic reforms. In April and May of 2011, China provided audio-visual and technical support to four media entities affiliated with the Syrian state, including the Syrian Arab News Agency (SANA). These donations are the only instances of Chinese aid to Syria recorded by the aid aggregator AidData for the year 2011. Though likely insignificant in monetary terms, they evidence an early interest in media narrative that has persisted.[7]No Author (2021) “AidData’s Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 2.0,” Aid Data, available at: … Continue reading

Phase 2: Limited Multilateral Support (2012-2017). The second phase of Chinese assistance to Syria set in as the incipient uprising intensified, armed conflict spread across the country, and donors adapted programme portfolios to the reasonable likelihood that the Government of Syria would buckle under pressure exerted by insurgent forces and the armed opposition. While many donor governments strategically embraced activities to build capacity in service, administrative, and civil society alternatives to the Government of Syria, China’s approach in this period was relatively even-handed, pursuing limited humanitarian support via the UN Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) and Regional Response Plan (3RP). In years in which it contributed to the HRP and 3RP, China’s donations averaged roughly 1.8 million USD (figure 1). Consistently ranking outside the top-50 donors to the Syrian crisis response, China has therefore commanded little notice as a humanitarian donor, and its last recorded contribution was a mere 33,808 USD in 2018[8]Financial Tracking Service, “Syrian Arab Republic 2021,” UN-OCHA, available at: https://fts.unocha.org/countries/218/summary/2021. The sum is an order of magnitude smaller than the contribution, … Continue reading Yet the UN architecture accounts for only one aspect of the broader humanitarian ecosystem, and Beijing has rerouted and significantly increased its support to Syria by working directly through the Syrian Government (see: figure 2).

In addition, China has also avoided antagonising Damascus by channelling its support to Syria’s neighbours, particularly in the first five years of conflict, in which its direction was highly dynamic and difficult to forecast. To that end, as of January 2016, Chinese Ambassador to the United Nations Liu Jieyi estimated that Beijing had provided nine packages of humanitarian aid worth 685 million yuan (approx. 100 million USD) to Syria and neighbouring countries. Although it is not immediately clear through which mechanisms this support was provided, or how it was divided among recipient states, available figures suggest that four-fifths (i.e., 80 million USD) or more supported neighbouring governments.[9]Baijie (2017).

Phase 3: Pivot toward Damascus (2017-2020). The third phase of Chinese assistance is distinguished by a major shift in the degree and kind of aid provided. This phase began in early 2017, following decisive territorial advances by the Syrian Government and its allies. Indeed, the largest single pledge of Chinese assistance to wartime Syria is a 16 million USD economic and technical cooperation agreement (ETCA) that was signed on 5 February 2017, only months after the Government’s recapture of Aleppo city from the Free Syrian Army, in December 2016. This timing is unlikely to be coincidental. The battle of Aleppo was arguably a decisive inflection point in the conflict, and its outcome relegated the armed opposition to besieged enclaves and marginal territories along Syria’s northern and southern frontiers. While attending the signing ceremony for the ETCA, Chinese Ambassador Qi Qianjin referred to the capture of Aleppo as marking “positive progress” in the “war on terror”.[10]Xinhua (2017), “China to donate humanitarian aid to Syria worth $16m,” The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, availableat: … Continue reading In all, 2017 marked a watershed for China’s support to Syria, which amounted to 54 million USD — 100 times more than the sum it provided in 2016 and nearly three times the aggregate value of aid it provided to Syria throughout the conflict to that point (figure 2).

In the ‘post-Aleppo’ framework that has defined China’s engagement with Syria ever since, Beijing has channelled almost all its humanitarian support directly to the Government of Syria. In total, the Chinese Embassy in Syria and the Syrian Planning and International Cooperation Commission (ICC) have signed five ETCAs, which constitute the monetary centrepiece of China’s bilateral assistance to wartime Syria. ETCAs have provided 60 million USD in total assistance. Details concerning the specific projects supported through these agreements are scarce.[11]SANA (2017), “Syria and China agree to a technical and economic agreement,” available at: https://www.sana.sy/?p=1117138 (AR). At least three of the agreements were placeholders which specified that the states would jointly agree to project allocations according to then-unspecified humanitarian needs. Reflecting on these packages, a SANA editor wrote for Chinese state media in January 2018 that “the leadership in Beijing has opted to play a more leading role in managing the conflict in Syria”, owing to Beijing’s desire to prevent “other major players” from “dicta[ing] its policies” on international issues.[12]Haifa Said (2018), “China’s humanitarian contribution to Syria adds to its int’l profile,” China.Org.Cn, available at: http://www.china.org.cn/opinion/2018-01/18/content_50239714.htm. Although China has not visibly sought to assert such leadership in multilateral institutions such as the UN Security Council, its humanitarian assistance to Syria has clearly evolved and expanded significantly as Beijing has grown more confident supporting the Government of Syria directly.

Phase 4: COVID-19 Diplomacy (2020-Present). A fourth phase of Chinese support has come in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Major armed violence in Syria has been frozen since March 2020, the month in which China and Syria signed their final ETCA. Since then, Chinese assistance has almost exclusively come in the form of support against COVID-19, including at least nine separate donations of Chinese-made vaccines, personal protective equipment (PPE), and other medical supplies.

This phase has demonstrated the unique extent to which Chinese assistance to Syria is publicised, particularly inside Syria. As of February 2022, Syria has received more than 8.3 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines through the WHO-supported COVAX facility, while China has committed an estimated 2.6 million vaccine doses.[13]World Health Organisation Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (2022), available at: … Continue reading As of early May 2022, SANA had published no fewer than 38 articles referencing Chinese bilateral support for COVID-related measures, noting that it “has spared no effort” to support Syria throughout the pandemic.[14]SANA (2021), “Syria receives half million doses of China’s Sinopharm COVID-19 vaccine,” available at: https://sana.sy/en/?p=254453. By comparison, SANA had referenced the (largely Western) WHO-supported COVAX facility only once. Such disparities highlight the information divide in Syria and point to the need for more thoughtfully articulated public messaging by donor agencies and implementers.

Part II: What Does Chinese Aid Signify for Syria’s Reconstruction?

The Damascus tilt in China’s humanitarian assistance from 2017 onward is mirrored in a renewed exploration of the commercial opportunities promised by post-war reconstruction, which the Government of Syria has eagerly promoted as a high-return windfall for investors. Indeed, the period since 2017 has seen a marked shift both in terms of Chinese diplomatic overtures toward Syria and in relation to nascent commercial activity. For instance, every Chinese firm that has registered in Damascus since the outbreak of the conflict in Syria has done so since 2017.[15]Syria Report (2021), “Report: Syria-China Economic Relations,” available at: https://syria-report.com/library/factsheet-syria-china-economic-relations/. While only 21 such firms have been founded, the registrations seemingly respond to strengthening political ties between China and the Syrian Government. In September 2017, Bashar al-Assad announced that China would receive preferential access to invest in reconstruction projects, along with Russia and Iran, rival powers whose posture toward Syria has favoured resource extraction and regional strategic interests, rather than economic rehabilitation.[16]The concession echoed statements made by the solicitous Syrian ambassador to China, Imad Mustafa. See: Syria Report (2021), “Report: Syria-China Economic Relations,” available at: … Continue reading In a 2019 television interview, al-Assad clarified his vision for China’s role in Syria’s reconstruction, pointing to a two-step process consisting of state-funded “humanitarian support” to rebuild vital infrastructure and private investment to rehabilitate Syria’s economy.[17]SANA (2019), “President al-Assad: “The Belt and Road Initiative” constituted worldwide transformation in international relations… There will be no prospect for US presence in Syria,” … Continue reading

State Support

Current evidence indicates that pledged Chinese support for reconstruction is designed to midwife eventual manufacturing and trade in the private sector. To date, the most significant state pledge is “up to” 2 billion USD promised for industrial parks to host Chinese private investment.[18]Syria Report (2021), “Report: Syria-China Economic Relations,” available at: https://syria-report.com/library/factsheet-syria-china-economic-relations/ and Harvey Morris (2018), “China extends … Continue reading It is not clear how, where, or when these investments would be made, or if they overlap with undisclosed agreements that are rumoured to exist, as in other BRI target nations.[19]Key informants note that so-called secret agreements between China and the Government of Syria are possible, as seen in other BRI client states. Syria Report (2017), “China offers first grant to … Continue reading Presently, Syria boasts four industrial cities, which are administratively designated hubs intended to incubate manufacturing and trade. They are situated in Damascus (Adra), Aleppo, Homs (Hessia), and Deir-ez-Zor.[20]Syria Report (2022), “Report: Syria’s industrial cities,” available at: https://syria-report.com/library/factsheet-syrias-industrial-cities/. In 2019, China strode more confidently into the Syrian market as the Chinese trade attaché in Damascus announced the opening of a trade office in Adra Industrial City to provide Chinese manufacturers a permanent foothold in Syria, indicating a willingness to piggyback off Syria’s existing industrial infrastructure.[21]Syria Report (2019), “China to set-up permanent trade centre near Damascus,” available at: https://syria-report.com/news/china-to-set-up-permanent-trade-centre-near-damascus/. In addition to these steps, according to al-Assad’s 2019 interview, China currently supports reconstruction through unspecified “humanitarian” projects to restore water and electricity networks, which may be realised through existing ETCAs.[22]It is likely these claims reference existing ETCAs. It is not immediately clear if these are among the six reconstruction projects that the Government of Syria has reportedly presented to Beijing in hopes of prompting support.

The Private Sector

Concrete private-sector investments have not been forthcoming, although Chinese firms have reportedly expressed interest in future investment. Al-Assad has described private investment in Syria as the “most important” stage of reconstruction and “the greatest challenge” of Syria’s post-war recovery.[23]Christopher Phillips (2022), “Syria: Joining China’s Belt and Road will not bring in billions for Assad,” Middle East Eye, available at: … Continue reading Although 1,000 companies reportedly attended the First Trade Fair on Syrian Reconstruction Projects in Beijing, it is not clear whether any major private-sector initiatives have taken place. According to al-Assad, the key impediments to Chinese participation in Syria’s reconstruction are insecurity and sanctions. In the 2019 interview, al-Assad observed that Syria’s physical security “is improving quickly and constantly,” and he noted that reconstruction activities were already being undertaken in reconciled areas captured by Government forces. Nonetheless, he acknowledged additional sources of insecurity, including ambiguity concerning taxes, investors’ rights, and other financial matters. Despite al-Assad’s optimistic view that legal measures would reassure outside investors, it is not clear that these issues have been addressed to the satisfaction of firms from China or elsewhere. To that end, Syria lands near the bottom of the World Bank’s global ranking for the ease of doing business, which muddies the business climate, although Chinese firms are practised at operating in contexts with weak institutions and limited accountability.[24]A comprehensive review of business conditions can be found here: World Bank Group (2020), “Doing Business 2020: Syrian Arab Republic), available at: … Continue reading In addition, the Syrian economy has for decades been dominated by private business interests co-opted as part of a state-driven economic agenda.[25]Katherine Nazime and Alexander Decina (2019), “No business as usual in Syria,” Carnegie Endowment, available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/79351. Although the conflict has altered the fortunes of key private-sector actors (e.g., Rami Makhlouf), the underlying risk of clashing with the interests of influential actors my be a barrier to Chinese investment, unless favourable relations can be guaranteed (see: Beyond Checkpoints: Local Economic Gaps and the Political Economy of Syria’s Business Community). Chinese investors, like Gulf investors and the Syrian business diaspora, have understandably hesitated to risk new business in the country, particularly given existing Iranian and Russian claims in key sectors, geographies, and state resources.[26]Sinan Hatahet (2019), “Russia and Iran: Economic influence in Syria,” Chatham House, available at: … Continue reading

Sanctions present an equally forbidding barrier to doing business in Syria. Not surprisingly, al-Assad has pointed to the absence of effective cash-transfer mechanisms as a major impediment to Chinese investment, likely in reference to difficulty accessing the SWIFT payment system or otherwise using international banks. To that end, the Government of Syria has encouraged Chinese firms to conduct business in Syria by “finding ways to evade sanctions.”[27]SANA (2019), “President al-Assad: “The Belt and Road Initiative” constituted worldwide transformation in international relations… There will be no prospect for US presence in Syria,” … Continue reading Despite the potential boon of reconstruction, private companies are likely to avoid such evasions, particularly given the example of the Chinese telecom giant Huawei, which came under legal pressure in the US over sanctions-busting dealings it conducted in Syria and Iran through third-party affiliates.[28]Steve Stecklow, Babak Dehghanpisheh, James Pomfret (2019), “Exclusive: New documents link Huawei to suspected front companies in Iran, Syria,” Reuters, available at: … Continue reading The enactment of the US Caesar Act in 2020 amplifies the deterrent effect of sanctions, although the absence of Western firms creates greater incentive for Chinese-Syrian cooperation in the long term.

Conclusion

Plagued by instability, beset by sanctions, and lacking in significant untapped resource wealth, Syria is presently unattractive for mass-scale foreign investment, despite its favourable geography vis-à-vis the BRI. Nonetheless, China’s recalibrated approach to humanitarian assistance in Syria since 2017 is among the strongest concrete indicators of its willingness to invest politically in its long-term relationship with the Government of Syria. This approach has, in some fashion, already secured China nominal access for future participation in reconstruction, albeit on terms that remain uncertain. In the long term, Chinese firms will have ample incentive to invest in Syria, an outcome that both the Chinese and Syrian governments have seemingly pursued. Chinese firms stand to benefit from multiple advantages in Syria, including:

- A demonstrated capacity to operate in sensitive and conflict-affected contexts undergirded by weak institutions and endemic corruption;

- Syria’s immense need for foreign support, which may impel local elites and Assad regime-linked power brokers to accept terms that are deferential to foreign investors; and

- A marketplace cleared of Western competitors by sanctions.[29]Syria Report (2021), “Report: Syria-China Economic Relations,” available at: https://syria-report.com/library/factsheet-syria-china-economic-relations/.

Nonetheless, if Syria is to attract investors, it will need to increase the absorptive capacity of the local market (e.g., by increasing Syrians’ purchasing power or engaging in reconstruction) or end its regional isolation to make it an efficient exporter of manufactures.

It is inapt to speak of a uniform Chinese approach to reconstruction in Syria. Rather, available evidence indicates a two-pronged approach combining some degree of state support and efforts to create an inviting climate for private-sector investment. At present, the extent to which either approach will be realised is in question, as is China’s willingness to integrate Syria into the BRI, for instance as a vital thoroughfare to a Mediterranean port like Tripoli, Lebanon, which would require extensive rail and possible motorway rehabilitation.[30]Samuel Ramani (2020), “How are Russia and China responding to the Caesar act?” Middle East Institute, available at: https://www.mei.edu/publications/how-are-russia-and-china-responding-caesar-act. Ultimately, it will be important to understand that China’s post-war engagement with Syria is likely to centre on shared strategic and economic interests, not the priorities of humanitarian reconstruction per se. Cost estimates for Syria’s reconstruction range from 250 billion to 400 billion USD. There is as yet no evidence that Beijing — or any other actor — is willing to foot this bill.

References[+]

| ↑1 | SANA (2022), “Syria, China sign MoU in framework of Silk Road Economic Belt Initiative,” available at: https://sana.sy/en/?p=260411 and OECD (2018), “China’s Belt and Road Initiative in the Global Trade, Investment and Finance Landscape,” available at: https://www.oecd.org/finance/Chinas-Belt-and-Road-Initiative-in-the-global-trade-investment-and-finance-landscape.pdf. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | While it is possible to debate the nature of this assistance, an overly rigid or narrow definition is arguably unhelpful. Indeed, Western aid funding is often described using the shorthand “humanitarian”, even when the assistance is delivered through a non-humanitarian funding stream, such as developmental assistance. |

| ↑3 | This issue is explored in-depth in Carsten Weiland’s Syria and the Neutrality Trap: The Dilemmas of Delivering Humanitarian Aid through Violent Regimes. |

| ↑4 | It is noted that some major donors choose to operate expressly in accordance with the wishes of the Government of Syria, which they view as the sovereign legal authority in the country. This view is the exception. |

| ↑5 | These estimates are based on public commitments announced by the Chinese state, Government of Syria, or both. Critically, a lack of transparency impedes independent verification, and many commitments are impossible to verify, given limited follow-through by concerned government entities and opacity concerning projects supported. See links in datasets below. See also: An Baijie (2017) “Xi says more help on way for Syria refugees,” China Daily, available at: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2017-01/20/content_28005354.htm. |

| ↑6 | It can be disputed at what point the uprising in Syria evolved into a conflict. For the purposes of this paper, “wartime Syria” encompasses the popular demonstrations that marked the beginning of the uprising, but preceded large-scale violence. |

| ↑7 | No Author (2021) “AidData’s Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset, Version 2.0,” Aid Data, available at: https://www.aiddata.org/data/aiddatas-global-chinese-development-finance-dataset-version-2-0. |

| ↑8 | Financial Tracking Service, “Syrian Arab Republic 2021,” UN-OCHA, available at: https://fts.unocha.org/countries/218/summary/2021. The sum is an order of magnitude smaller than the contribution, for instance, of institutional donors like the American asset management firm BlackRock, which contributed 424,300 USD. |

| ↑9 | Baijie (2017). |

| ↑10 | Xinhua (2017), “China to donate humanitarian aid to Syria worth $16m,” The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, availableat: http://english.www.gov.cn/news/international_exchanges/2017/02/06/content_281475560526100.htm. |

| ↑11 | SANA (2017), “Syria and China agree to a technical and economic agreement,” available at: https://www.sana.sy/?p=1117138 (AR). |

| ↑12 | Haifa Said (2018), “China’s humanitarian contribution to Syria adds to its int’l profile,” China.Org.Cn, available at: http://www.china.org.cn/opinion/2018-01/18/content_50239714.htm. |

| ↑13 | World Health Organisation Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (2022), available at: http://www.emro.who.int/syria/news/covax-supply-update-on-covid-19-vaccination-in-syria-9-february-2022.html?format=html. |

| ↑14 | SANA (2021), “Syria receives half million doses of China’s Sinopharm COVID-19 vaccine,” available at: https://sana.sy/en/?p=254453. |

| ↑15, ↑29 | Syria Report (2021), “Report: Syria-China Economic Relations,” available at: https://syria-report.com/library/factsheet-syria-china-economic-relations/. |

| ↑16 | The concession echoed statements made by the solicitous Syrian ambassador to China, Imad Mustafa. See: Syria Report (2021), “Report: Syria-China Economic Relations,” available at: https://syria-report.com/library/factsheet-syria-china-economic-relations/ and Dan Hemenway (2018), Chinese strategic engagement with Assad’s Syria,” Atlantic Council, available at: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/syriasource/chinese-strategic-engagement-with-assad-s-syria/. |

| ↑17, ↑27 | SANA (2019), “President al-Assad: “The Belt and Road Initiative” constituted worldwide transformation in international relations… There will be no prospect for US presence in Syria,” available at: https://sana.sy/en/?p=180579. |

| ↑18 | Syria Report (2021), “Report: Syria-China Economic Relations,” available at: https://syria-report.com/library/factsheet-syria-china-economic-relations/ and Harvey Morris (2018), “China extends helping hands to rebuild Syria,” China Daily, available at: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201802/10/WS5a7e4f48a3106e7dcc13bee2.html. |

| ↑19 | Key informants note that so-called secret agreements between China and the Government of Syria are possible, as seen in other BRI client states. Syria Report (2017), “China offers first grant to Syria since 2011,” available at: https://syria-report.com/news/china-offers-first-grant-to-syria-since-2011/. |

| ↑20 | Syria Report (2022), “Report: Syria’s industrial cities,” available at: https://syria-report.com/library/factsheet-syrias-industrial-cities/. |

| ↑21 | Syria Report (2019), “China to set-up permanent trade centre near Damascus,” available at: https://syria-report.com/news/china-to-set-up-permanent-trade-centre-near-damascus/. |

| ↑22 | It is likely these claims reference existing ETCAs. |

| ↑23 | Christopher Phillips (2022), “Syria: Joining China’s Belt and Road will not bring in billions for Assad,” Middle East Eye, available at: https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/syria-china-assad-financial-rescue-unlikely. |

| ↑24 | A comprehensive review of business conditions can be found here: World Bank Group (2020), “Doing Business 2020: Syrian Arab Republic), available at: https://www.doingbusiness.org/content/dam/doingBusiness/country/s/syria/SYR.pdf. |

| ↑25 | Katherine Nazime and Alexander Decina (2019), “No business as usual in Syria,” Carnegie Endowment, available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/79351. |

| ↑26 | Sinan Hatahet (2019), “Russia and Iran: Economic influence in Syria,” Chatham House, available at: https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/2019-03-08RussiaAndIranEconomicInfluenceInSyria.pdf. |

| ↑28 | Steve Stecklow, Babak Dehghanpisheh, James Pomfret (2019), “Exclusive: New documents link Huawei to suspected front companies in Iran, Syria,” Reuters, available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-huawei-iran-exclusive-idUSKCN1P21MH |

| ↑30 | Samuel Ramani (2020), “How are Russia and China responding to the Caesar act?” Middle East Institute, available at: https://www.mei.edu/publications/how-are-russia-and-china-responding-caesar-act. |