Syria Update Digest

On 8 July, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad visited Aleppo City for the first time since 2011, touring Aleppo Thermal Power Station, inaugurating the Tal Hasel water pumping plant in rural Aleppo, and performing Eid al-Adha prayers at Sahabiy Abdallah bin Abbas mosque. The visit is freighted with symbolic importance and potential implications for the aid community. Al-Assad’s visits to key infrastructural facilities highlight the Syrian Government’s needs in the water and electricity sectors and raise questions over which actors are able to satisfy these needs, and to whose benefit. Indeed, al-Assad’s “victory lap” to Aleppo, in which he appeared keen to demonstrate Damascus’s emphasis on expanding service provision, belies the Syrian Government’s dependence on outside actors, including Iran, for support in key sectors.

- On 12 June, the UN Security Council (UNSC) extended the cross-border aid delivery mechanism for another six months, till 10 January 2023. The new resolution widens the scope of early recovery to include electricity services, with aid actors holding the immense responsibility of navigating an increasingly contentious environment.

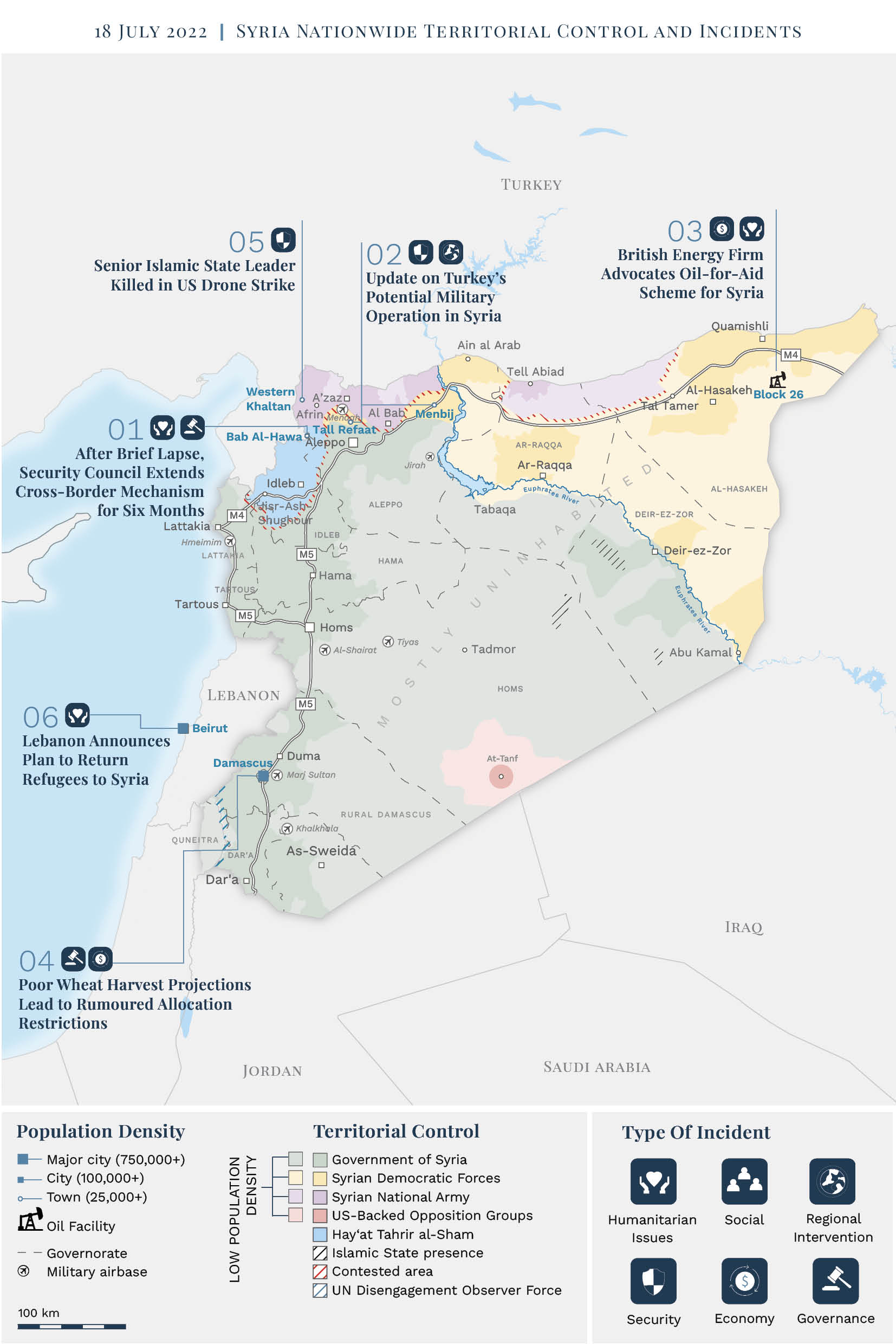

- Turkey maintains it will launch its incursion into northern Syria “without delay” amid continued opposition from its NATO allies as well as the Government of Syria and its backers Russia and Iran. No incursion is likely to take place without the assent of guarantor states at a trilateral “Astana” summit in Tehran on 19 July.

- Gulfsands Petroleum, a small British oil company, has begun to publicly advocate a “win-win-win” oil-for-aid scheme in Syria as a means of funding humanitarian activities. The initiative is a moonshot that seeks to capitalise on international frustration over rising energy prices and donor fatigue in Syria and entails numerous complications.

- On 9 July, Syria’s Minister of Agriculture, Muhammad Hassan Qatna, said that Syria’s expected wheat production will be 1.7 million tonnes this year, against a need of 3.2 million tonnes, as rumours spread that bread subsidies will be cut. Another poor harvest amid global wheat shortages due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine bodes ill for Syria’s food-insecure population.

- On 12 July, US Central Command announced it had killed Maher al-Agal, a prominent Islamic State (IS) leader, in a drone strike in Western Khaltan, north of Jandairis in Aleppo Governorate. While strikes that kill senior IS figures grab headlines, they are likely to have only a limited impact on the overall capacities of the group.

- On 6 July, Lebanon’s interim Minister for the Displaced, Issam Charafeddine, revealed a plan to deport up to 15,000 Syrian refugees per month to Syria. While likely an attempt to solicit international support, the measure may also signal a willingness to deport at least some Syrians, given Lebanon’s crippling financial crisis.

In-Depth Analysis

On 8 July, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad visited Aleppo City for the first time since 2011, touring the rehabilitated Aleppo Thermal Power Station, inaugurating the Tal Hasel water pumping plant in rural Aleppo, and performing Eid al-Adha prayers at Sahabiy Abdallah bin Abbas mosque. The visit is freighted with symbolic importance and potential implications for the aid community. Aleppo is in some respects the major Syrian city that has been most profoundly altered by the conflict. It was previously the largest city in Syria, the country’s industrial dynamo, and one of its historical cultural hubs. Its centrality to Syria’s political economy made it the focus of heavy fighting and intense siege, with much of the urban landscape ultimately being destroyed during its recapture by Government of Syria forces in December 2016. Since then, it has been the focus of intense speculation over sectoral rehabilitation, Gulf investment in Syria, Iranian influence, and eventual reconstruction — although action in these areas by Damascus has been limited, and aid actors have undertaken limited activities that pale in comparison with needs.

Al-Assad’s visits to key infrastructural facilities highlight the Syrian Government’s needs in the water and electricity sectors and raise questions over which actors are able to satisfy these needs, and to whose benefit. Indeed, al-Assad’s “victory lap” to Aleppo, in which he appeared keen to demonstrate Damascus’s emphasis on expanding service provision, belies the Syrian Government’s dependence on outside actors, including Iran. For donors to implement in Aleppo, cautious safeguarding measures are required to avoid overlapping with problematic local actors, such as Iran- or Assad regime-linked figures.

Cui bono?

The rehabilitation of Aleppo Thermal Power Station will have an important but limited impact on local energy needs; it is expected to generate 200 megawatts (MW) of electricity, against Aleppo’s total demand of 900 MW. Syria’s electricity sector has suffered huge blows during the war as a result of the destruction of infrastructure and the high price and unavailability of fuel, leading to severe rationing and frequent outages. With an estimated domestic production of 1,500-2,000 MW per day against a need of 5,000, Syria is no longer the net exporter of electricity it was before the war. The work in Aleppo was carried out by the Iranian MAPNA Group, an industrial conglomerate reportedly affiliated with the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps, as part of a purported 123.5 million EUR contract signed in September 2017. Iranian involvement in Syria’s power sector follows a 2017 memorandum of understanding for cooperation in the electricity sector which included a list of projects that would total around 12.4 percent of Syria’s pre-war power generation should they go ahead. Likely funded by an Iranian credit line (see: Syria Update 16 May 2022), Tehran will seek to recoup the cost of its adventure in Syria, maintaining its geostrategic position, building local influence, and looking for economic concessions where possible.

Iran-linked militias may be among the ultimate beneficiaries of the rehabilitation of the Tal Hasel pumping station, which is expected to irrigate 8,500 hectares of farmland producing cereals, cotton, vegetables, and olive trees in Aleppo’s southern plains. Supported by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), which supplied equipment and construction services, the rehabilitation of the station will seek to revive the Queiq River, which runs through several neighbourhoods in Aleppo city and villages further south that saw heavy fighting and were recaptured by the Government of Syria with Iranian militia support. Some of these towns and villages are now considered to be under the control of Iranian militias, with their original populations displaced to camps in Idleb.

The path to early recovery

Al-Assad symbolically reasserting his presence in Aleppo is unlikely to augur further investment in reconstruction on the part of the Government of Syria, given its limited fiscal capacity and the scale of the work needed. Given this vacuum, Iran likely finds in rehabilitation of key sectors an opportunity to increase its influence, gain economic concessions, and further entrench itself across the so-called “Shia crescent”, the belt of territory stretching from the Iran-Iraq border through Syria and Lebanon, into Palestine. For the donor community, supporting sectors like electricity and water are essential for tackling Syria’s multiple economic crises (see: Syria Update 4 July 2022) and meeting urgent humanitarian needs. The longer donors wait to engage in these sectors — and others — the more entrenched and involved other malign actors, such as those linked with Iran, are likely to become. This is not to say that Syria’s allies will fund reconstruction if Western donors remain on the sidelines. Rather, Russia and Iran — as well as China (see: China in Syria: Aid and Trade Now, Influence and Industry Later?) — may exploit Syria’s needs to entrench their own interests.

The inclusion, at Russia’s behest, of electricity as a sector to be targeted by early recovery programming in the Security Council’s extension of the cross-border mechanism for delivering aid to northern Syria (see below) may prompt donor governments to more actively contemplate activities that boost Syria’s capacity for power generation. The case of Aleppo illustrates some of the challenges that await. Particularly in key communities like Aleppo, questions related to the beneficiaries of any activity will be fundamental to mitigating unintended harms and avoiding actions that cement in place conditions that disadvantage the vulnerable and the displaced. The electricity sector is also highly centralised, necessitating some degree of coordination with Government of Syria institutions, which raises concerns over sanctions, compliance, and the notional division between Assad regime figures and technical sectoral activity. Such considerations will present further future reputational risk for aid actors operating in areas like Aleppo, where already the NGO sector faces significant Government of Syria control. Operating in Government of Syria areas, particularly when working in strategically important sectors such as electricity, will require comprehensive safeguarding measures to avoid programmatic and reputational risks, with partnerships subjected to close monitoring and evaluation.

Whole of Syria Review

After Brief Lapse, Security Council Extends Cross-Border Mechanism for Six Months

On 12 July, the UN Security Council (UNSC) adopted Resolution 2642, extending the UN cross-border aid delivery mechanism in northern Syria for six months, until 10 January 2023. The renewal followed a dramatic two-day lapse in the mandate owing to obstinate back-and-forth between the Western bloc — in effect, the representatives of the major Syria donors — and the Russian-Chinese bloc — allies of the Government of Syria (see: China in Syria: Aid and Trade Now, Influence and Industry Later?). While the aid community was united in its support for a 12-month extension, Russian officials refused to countenance a renewed mandate lasting longer than 6 months. On 8 July, Russia and China vetoed a one-year extension of the UN mechanism proposed by penholders Ireland and Norway. That same day, the US, UK, and France vetoed a Russian counter-proposal that the Council would ultimately pass, after succumbing to pressure, on 12 July.

Resolution 2642 makes several small, but important changes. Most notably, the mandate’s extension in January will require another vote, following a “special report on humanitarian needs” submitted by the Secretary-General. The resolution also requires the Secretary-General to provide a monthly briefing to the Council and bi-monthly reports on the implementation of this and previous UNSC resolutions by all parties in Syria. It also calls for an “Informal Interactive Dialogue” to be held with “donors, interested regional parties, and representatives of the international humanitarian agencies operating in Syria.” In addition, the text adds reference to the electricity sector as one of the essential services to be targeted by early recovery programming, which was absent in the previous Resolution 2585.

Focusing on electricity, amping up pressure on donors

The newly adopted resolution highlights the widening rift within a polarised Security Council, reflecting the contentious environment donor governments and the Syrian aid response as a whole must navigate. Russia may be isolated internationally, but the vote demonstrates its continued ability to leverage its veto power and the international community’s concern over humanitarian needs in northern Syria to influence humanitarian aid in the country. Though better than an abrupt end to the cross-border mandate, the six-month extension complicates aid planning and implementation, which are now liable to expire in the middle of winter, a time of heightened needs. As the aid and donor community scrambles to provide practical definitions of early recovery, Russia could use references to electricity as leverage in negotiations ahead of the next vote in six months. While the Security Council itself cannot explicitly dictate how Western donors allocate their funding in Syria and which sectors or projects they target, the perennial debate over the cross-border resolution allows Russia to do just that. While electricity is a priority need in Syria, including in Government areas, the fate of the cross-border mechanism may now hinge on the international community’s ability to satisfy Russia’s seeming demand for more work in this area. It is little wonder that analysts and even some donors are more vocally calling for consideration of a so-called ‘Plan B’ alternative to the UN cross-border system.

Update on Turkey’s Potential Military Operation in Syria

This is the fourth update on Turkey’s potential military operation in northern Syria (see: Syria Update 20 June 2022). Turkey has reportedly continued to deploy reinforcements to its areas of control, while the US and Russia maintain opposition, at least rhetorically.

- Turkey insists the operation will go ahead “without delay.” On 10 July, Turkey’s Defence Minister announced that the operation would not be cancelled, although no date was given. Turkey has reportedly continued to send materiel to its troops and its Syrian National Army proxies in Aleppo.

- Trilateral “Astana format” meeting in Tehran to discuss Syria. On 12 July, the Kremlin’s spokesperson Dmitry Peskov said that Russian President Vladimir Putin will travel to Tehran to meet with Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan for “peace talks” concerning Syria. Turkey’s planned operation is likely to be the main issue on the agenda.

- The US emphasises the threat of Islamic State (IS). US officials highlighted the risk of further IS attempts to free its fighters held in northeast Syria’s prisons (see: Syria Update 31 January 2022) should security in the region be further destabilised. Similar risks have been highlighted by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in the past when threatened by a Turkish incursion.

- SDF denies forming a joint operations room with the Government of Syria. While the SDF raised the possibility of a merger with Syrian Government forces to counter Turkey (see: Syria Update 4 July 2022), on 13 July, SDF spokesperson Aram Hanna said that no such agreement had been reached.

British Energy Firm Advocates Oil-for-Aid Scheme for Syria

Gulfsands Petroleum, a small British oil company, has begun to publicly advocate a “win-win-win” oil-for-aid scheme in Syria as a means of easing humanitarian needs and funding “economic and security projects” across the country. The plan would provide legal aegis for the return of foreign firms to Syria’s oil sector and establish a UN-administered trust fund to manage energy receipts to which the Government of Syria is legally entitled. Although calibrated to provide market-oriented financing as donor interest in Syria ebbs, the precise mechanism by which aid priorities would be supported through the mechanism is not immediately clear. At current oil prices, Syria’s oil sector could gross roughly 20 billion USD annually, according to the managing director of Gulfsands, John Bell.

Drumming up interest in Syrian output

The initiative is a moonshot that seeks to capitalise on international frustration over rising energy prices and donor fatigue in Syria. The plan entails numerous complications, however.

- The Syrian oil sector is unlikely to reach capacity quickly. As pitched by Bell, the plan envisions boosting Syrian oil production to 500,000 barrels per day, a level that is near Syria’s record high, and a dramatic boost from output of roughly 350,000 barrels per day prior to the conflict. Though brisk demand in the global energy market could drive output, such a boost would likely require additional infrastructure that would be costly and slow to install.

- It’s not clear how much cash it would deliver. The financial prospects of the scheme may be less promising than advertised. The 20 billion USD in returns touted by Gulfsands likely assumes steady (or rising) oil prices and that sales will occur predominantly or entirely on the open market. Yet local Syrian actors would likely seek to divert output to meet local demand, an imperative that donor governments aiming to meet humanitarian needs must consider. In addition, oil firms could see one-third of receipts under the scheme.

- Syrian stakeholders may say ‘no’. Buy-in among local power brokers is difficult to forecast. Though it may be tempted by the return of foreign businesses, the Government of Syria is unlikely to support an arrangement that formally relinquishes its control over the country’s resource wealth. Agreement in the northeast, home to the country’s major oil reserves, is also far from guaranteed. Under the Trump administration, northeast Syria benefitted from a short-lived sanctions waiver that brought in technical assistance from Delta Crescent Energy, an entity linked to a former Gulfsands executive (see: Syria Update 17 August 2020). The oil-for-aid scheme is different, however. It would marginalise the Government of Syria on a scale that is sectorally comprehensive and explicitly international. Although the Syrian Democratic Forces, currently the main beneficiaries of Syria’s production, may use the existence of such a plan as negotiating leverage against Damascus, they will be hard-pressed to endorse it in practice when they are looking to the Syrian Arab Army for protection against a possible military incursion by Turkey.

- International scrutiny can also be anticipated. Reference must be made to the scandal-ridden oil-for-food scheme administered by the UN in heavily sanctioned 1990s Iraq. To begin, Russia will likely veto the duplication of that system, which would weaken its Government of Syria allies financially and politically. The Iraq programme offers lessons learned for Western actors, too. The UN-supported oil exchange netted Saddam Hussein’s regime an estimated 1.7 billion USD in kickbacks and 10.9 billion USD through smuggling. It also entrenched a broader system of corruption. It is estimated that half of the firms that participated in the scheme paid douceurs to win contracts or gain access.

Donor governments working in Syria should reflect on such conditions as they consider the potential for new approaches to deal with Syria’s needs in the long term.

Poor Wheat Harvest Projections Lead to Rumoured Allocation Restrictions

On 9 July, Syria’s Minister of Agriculture, Muhammad Hassan Qatna, announced that Syria’s expected wheat production will be 1.7 million tonnes this year, against a need of 3.2 million tonnes. The news followed claims by the pro-Government Al-Ba’ath newspaper on 7 July that the Syrian Government’s Ministry of Internal Trade is preparing to decrease wheat allocations to governorates by 10 percent and limit their ability to request additional allocations. According to the same source, the Government is also angling to reduce the weight of the subsidised bread bundle from 1,100 to 1,000 grammes and increase its price from 200 to 300 SYP. Amr Salem, the Minister of Internal Trade, denied these claims.

Growing pains

While an increase on last year’s historically low output of 1.05 million tonnes (see: Syria Update 10 January 2022), another year of poor harvests amid global wheat shortages and high prices due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (see: Syria Update 7 March 2022) bodes ill for Syria’s food insecure population. The country is facing extreme water scarcity caused by droughts and poor water management (see: Syria Update 4 July 2022), as well as limited fuel availability and high prices (see: Syria Update 23 May 2022). That claims over allocations and subsidy cuts were made by a pro-Government newspaper suggests the Government of Syria is “testing the waters” before making a final decision. Although denied by the minister, some form of subsidy cut is likely to go ahead as the Syrian Government wrangles with persistent budgetary shortfalls. This will exacerbate Syria’s cost-of-living crisis and likely significantly increase the need for food aid. In the long term, adaptation of Syria’s agricultural production to a drier climate and resilience against drought will be required.

Senior Islamic State Leader Killed in US Drone Strike

On 12 July, US Central Command announced it had killed Maher al-Agal, a prominent IS leader, in a drone strike in Western Khaltan, north of Jandairis in Aleppo Governorate. The Pentagon identified al-Agal as the leader of IS in Syria and also claimed another, unidentified senior IS official was seriously injured in the strike. Al-Agal was reportedly a prominent IS commander in Ar-Raqqa until its liberation in 2017. In a statement, US President Joe Biden said that the strike “significantly degrades the ability of ISIS to plan, resource, and conduct their operations in the region.”

Another one bites the dust

While frequent missions and strikes that kill senior IS figures grab headlines, they are likely to have a limited impact on the overall capacities of the group. Even after the death of the group’s leader, Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurayshi, in a US raid earlier this year (see: Syria Update 7 February 2022), IS has continued to carry out operations throughout Syria, including claiming responsibility for bombings near Damascus (see: Syria Update 23 May 2022). Since its territorial defeat in 2019, IS has reverted to insurgency, guerrilla warfare, and a largely decentralised structure that enables it to carry out hit-and-run attacks with the aim of sowing chaos and weakening its enemies. Defeating IS requires tackling the underlying drivers of radicalisation, including poverty, disenfranchisement, and social alienation (see: Social Cohesion in Support of Deradicalisation and the Prevention of Violent Extremism). Aid actors working throughout Syria should understand that the threat of IS remains largely unchanged despite counterterrorism operations to kill its leaders and should maintain strong security and contingency plans amid the risk of IS attacks.

Lebanon Announces Plan to Return Refugees to Syria

On 6 July, Lebanon’s interim Minister for the Displaced, Issam Charafeddine, revealed a plan to deport up to 15,000 Syrian refugees per month to Syria. A committee including the interim Prime Minister Najib Mikati, Charafeddine, six other ministers, and the country’s General Security service has reportedly been working on a proposal since March, which entails gradually repatriating Lebanon’s estimated 1.5 million Syrian refugees. The proposal follows remarks by Lebanon’s Interim Foreign Minister Abdallah Bou Habib at the Arab League consultative ministerial meeting in Beirut, Lebanon on 2 July, in which he stated that sending Syrian refugees to their homeland was in Lebanon’s national interest. The proposal would require the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to suspend monthly aid to 15,000 refugees, postponing payment until they return to Syria. UNHCR dismissed the proposal, arguing that forced return of Syrian refugees could have perilous consequences for returnees. According to Charafeddine, Syria’s Local Administration and Environment Minister, Hussein Makhlouf assured him that the Syrian Government welcomed the plan and that they could provide temporary housing for those deported from Lebanon in areas that are “entirely safe.”

Stuck between a rock and a hard place

Lebanon is suffering from a debilitating financial crisis, which is pushing the country toward further social atomisation and disintegration of the central state apparatus. In the absence of an international plan for the many Syrian refugees in Lebanon, there is the possibility that the Lebanese administration is sincere in its intentions to deport Syrian refugees, even if its capacity to do so on a sustained and systematic basis remains in question. However, it is also plausible (and likely) that the administration is posturing to secure more financial assistance. Nonetheless, if the Lebanese government is successful in deporting at least some Syrian refugees, the ramifications will be far-reaching: it would put many returnees in imminent danger; it would set a dangerous precedent for other host countries with high numbers of Syrian refugees, such as Jordan and Turkey; and it would validate the Syrian Government’s claim that Syria is a “safe” place to return to. Aid actors should be prepared for the prospect of forcible deportation from Lebanon.

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below..

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

Algeria: We Do Not Object to Syria Reclaiming Its Seat in the Arab League

What does it say? The Algerian Foreign Minister stated that his country “does not mind Syria returning to take its seat in the Arab League,” and that “Algeria will make every effort to bring unity and strengthen the common Arab cause in order to meet collective challenges.”

Reading between the lines: Algeria has maintained good relations with the Syrian Government throughout the conflict, so its position is not surprising. However, Syria’s return to the Arab League in the near future is unlikely as it requires consensus, with Saudi Arabia and Qatar maintaining opposition.

Repatriation of children and mothers from North-East Syria (05 Jul. 2022)

What does it say? France has repatriated 35 children and 16 mothers from camps in northeast Syria. The children were handed over to child support services, while mothers were handed over to the relevant judicial authorities.

Reading between the lines: Repatriation followed by judicial processes is the only durable solution for foreign nationals in the camps of northeast Syria. However, if repatriations continue at the current rate, it will take 30 years for all foreign camp residents to return home.

What does it say? The Syrian Ministry of Interior launched a new service for the electronic issuance and renewal of passports which allows citizens to download the application documents, pay fees, and book an appointment online.

Reading between the lines: This is the latest in a series of attempts to resolve Syria’s long-standing passport issuance crisis, with Syrians waiting months to receive a new passport. Previous iterations of the online platform have had little success (see: Syria Update 28 February 2022; Syria Update 13 December 2021).

A new conflict management strategy for Syria: Creating a Safe, Calm and Neutral Environment

What does it say? The pursuit of peace in Syria is in crisis. There is stalemate on the battlefield, the Constitutional Committee has proved ineffectual, and the UN’s ‘step-for-step’ approach suffers from flawed conceptual underpinnings as well as a lukewarm reception.

Reading between the lines: This reality should act as a marker for recalibrating Western policy on Syria beyond the current focus on sanctions, accountability, and humanitarian aid.

Jordan Is Far From Normalization With Syria

What does it say? In 2021, Jordan was criticised for an apparent warming of relations with the Syrian Government due to the opening of a border crossing and dialogue between the two countries’ Heads of State and Ministers of Defence and Foreign Affairs.

Reading between the lines: While the two governments are interested in cooperating on trade and border security, an uptick in clashes related to the Captagon drug trade and Iran-aligned influence in southern Syria has ensured that Jordan is still a long way from normalisation with Syria.

Non-Governmental Organisations in Aleppo: Under Regime Control and at its Service

What does it say? The Syrian Government uses various tools to bolster its domination over registered local NGOs and their international backers, primarily to serve its own interests.

Reading between the lines: Syrian Government control over the NGO sector poses significant concerns for aid actors seeking to work in Government-held areas. Partnerships on the ground require careful due diligence and third-party monitoring to ensure that funds are not used to empower malign actors.