More than eleven years into the conflict in Syria, millions of Syrians are displaced inside their country, with little obvious prospect of return to their home areas. These Syrians are largely concentrated on the country’s peripheries, in areas outside Syrian government control. Many fear reprisal from vindictive authorities or neighbours, while others, after destructive battles over their areas of origin, have no real homes to return to. Some 2 million displaced people have returned home since 2018 as large-scale military conflict has partially subsided, but nearly 6.7 million are still displaced inside the country.[1]Source: Humanitarian Needs Assessment Programme. Of these, 19 percent (approx. 1.3 million) live in camps, most of them (approx. 1.1 million) in informal (unplanned) settlements.

Syria’s most significant displacement camps have become increasingly resilient to initiatives meant to facilitate residents’ return. International responses have, as a result, tended towards accommodating and reproducing the status quo, providing some relief and piecemeal support for local integration. This comes at a cost, however – first and foremost for Syrians languishing in displacement, but also to local authorities and international donors maintaining and sponsoring these settlements.[2]Humanitarian Needs Assessment Programme, “Shelter Situation 2021 IDP Report Series.”

A more locally grounded approach is therefore warranted. Indeed, solutions for Syria’s displaced will not be found in broad, one-size-fits-all frameworks. Residents of various camps face different challenges, trajectories, and possibilities for long-term solutions. Identifying durable solutions for these Syrians requires a better understanding of the discrete, localised concerns that are responsible for their initial displacement, and which impede return, resettlement, and reintegration.

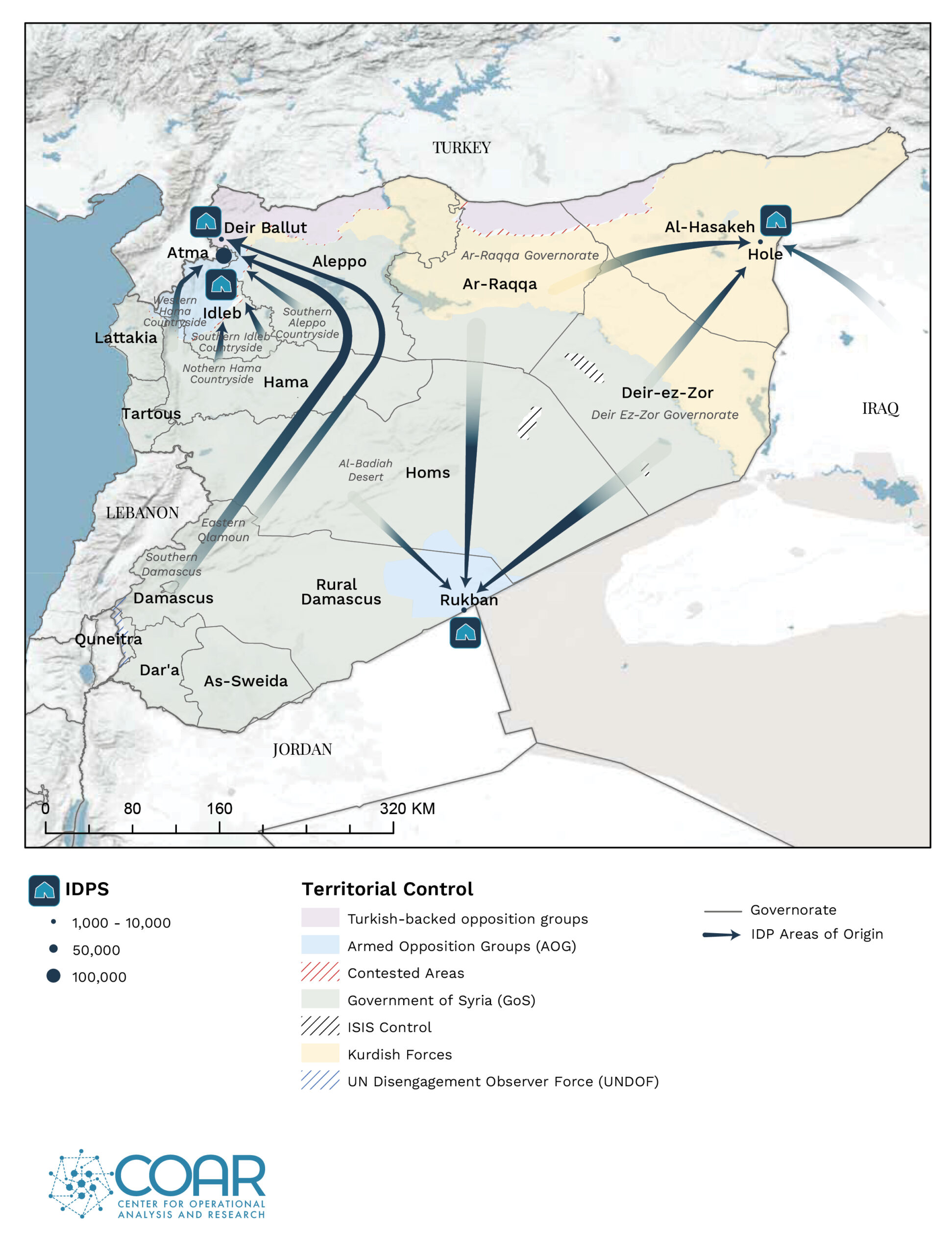

The paper that follows is an attempt to further this discussion by evaluating conditions in major, particularly intractable IDP camps across Syria’s zones of control: Atma (Idleb), Rukban (Homs), Hole (Al-Hasakeh), and Deir Ballut and Muhammadiya (Aleppo). No IDP camps in Government of Syria areas have been included in this study, as IDPs in government territory have largely been integrated within existing urban contexts. Drawing on interviews with camp residents and desk research, this paper provides a comparative overview of the background of the camps, the key challenges to residents’ return, and a forward-looking assessment of the options available for residents and international aid actors. It is our hope that the aspirations of camp residents as articulated here can contribute to donor-level and aid agency thinking concerning the future of displaced Syrians.

Key Findings

- The past and future trajectories of camp populations across Syria speak not to one singular Syrian displacement crisis, but multiple displacement crises with different dynamics and differing solutions that must be understood historically, if they are to be addressed effectively. For instance:

- Hole and Rukban camps are viewed by their residents as de facto detention facilities, with limited prospects for departure owing to social, political, and economic barriers to return.

- By contrast, camps in Syria’s northwest offer significantly more freedom of movement. Although return is improbable, resettlement decisions are constrained not by mobility per se, but by limited financial resources and the absence of viable areas in which to settle.

- With Hole as a notable exception, camp populations are largely structured around communities of origin, and such communities remain tightly bound. Whether inhabiting distinct camps in the Atma cluster, or self-organised through committees in Rukban, entire communities were displaced together — and largely wish to either remain, or move, together.

- Unless third-country resettlement options are offered, Syrians displaced to the northwest are likely to constitute a quasi-permanent camp population, as return to Government of Syria areas is unlikely without a comprehensive resolution of the conflict. The international community’s inability to provide dignified and sustainable alternatives is a contributing factor to resettlement in areas such as Afrin.

- Addressing the most intractable cases of displacement in Hole and Rukban requires political will to alter the status quo. Stepped up repatriation efforts for foreigners in Hole, and negotiating humanitarian access to Rukban through either Jordan or across conflict lines with the Government of Syria, are necessary to alleviate pressure in both settings in the absence of viable return initiatives.

Recommendations

- Map demographics. Undertake a mapping of camp demographics and conduct a dual-track assessment of A) residents’ communities of origin, immediate needs, future aspirations, and B) the diverse array of barriers to resettlement (where possible) or reintegration (as necessary). Such information must be effectively shared and accessible within a do no harm framework if it is to guide funding priorities and shape further analysis and decision-making.

- Assess dignified shelter options and tent alternatives. Plans have been formulated to provide residents of many northwest Syria camps with semi-permanent shelters in lieu of tents. Plans such as these should be considered as a means of providing dignified shelter and protection support to the most vulnerable camp residents.

- Identify greater early recovery and livelihoods opportunities. Aid-sector employment and cash-for-work are key sources of income in Syria’s camps. Aid actors should look to scale up long-term support to residents, with a particular focus on providing sustainable livelihoods and opportunities. Residents interviewed suggested funding for small enterprises or projects to provide incomes would be beneficial for those in the camp as they seek agency to enable long-term autonomous decision-making.

- Education and training. Public schools in northwest Syria are already dependent on volunteers and NGO funding and staffing to operate. However, such support is variable amid concerns over interference by the Syrian Salvation Government.[3]COAR, “Syria Update 14 February 2022.” Education should be a priority for the aid sector, given its importance in counter-radicalisation and providing sustainable futures for residents apart from armed group activity.

- Leverage community organisation for solutions. IDP settlements in many cases mirror communities of origin and are often led in effect by ad-hoc committees or local notables. These serve as critical conduits between the population and de facto authorities and should be identified as intermediaries when planning and seeking community buy-in for humanitarian interventions and long-term solutions.[4]COAR, “Intermediaries of Return,” 7 October 2019.

- Step-up MHPSS support. In Hole camp in particular, there is scope to address acute needs through psychosocial support and mental health services to residents to cope with the traumas associated with the protracted conflict and with residence in Hole itself. In addition, increase childhood education, protection, livelihoods, and vocational activities to foster resilience among residents, mitigate abuses, and reduce the incentives to rely on IS.

- Do no harm. In northern Aleppo, displaced populations with few options have settled in villages and properties vacated by other displaced communities, including throughout Afrin. Aid work in these areas must be sensitised to ensure that efforts to support some displaced populations do not contribute to the dispossession of others.

1. Atma Camp

Current Population: 180,995 (May 2022)[5]OCHA, “IDP Sites Integrated Monitoring Matrix (ISIMM), May 2022,” 15 June 2022.

Peak Population: 222,894 (August 2021)[6]OCHA, “IDP Sites Integrated Monitoring Matrix (ISIMM), August 2021,” 17 September 2021.

Founded: 2012

Location: Atma, Harim district, Idleb Governorate

Considered the largest congregation of IDPs in Syria, Atma is a cluster of over one hundred camps near Atma village in the Dana sub-district of Harim, northern Idleb Governorate, with a total population estimated at between 140,000[7]Assistance Coordination Unit, “IDPs Camps Monitoring Study May 2022.” and 180,000.[8]OCHA, “IDP Sites Integrated Monitoring Matrix (ISIMM), May 2022,” 15 June 2022. Located on the border with Turkey’s Hatay province, the first camp was founded in 2012 as fighting in Aleppo and Idleb drove thousands to flee their homes and attempt to cross into Turkey. The population of Atma camp was estimated to be around 10,000 people in late 2012,[9]The New Humanitarian, “IDPs brace for winter in rebel-controlled camps,” 19 December 2012. and the numbers swelled in 2013 and 2014 as conflict intensified in Syria’s northwest. The last major wave of displacement to Atma camp took place in 2019 and early 2020 following the Northwestern Syria offensive launched by Syrian government forces in northern Hama and southern Idleb.[10]COAR, “Syria Update 25-31 July 2019.”

Better understood as a collection of camps rather than a cohesive whole, each individual camp is largely inhabited by people from the same town or village, providing networks and social support systems. Nevertheless, Atma residents largely share the same problems: slim prospects of return to their now Government of Syria-held homes; poor winterisation; a lack of protection from flash floods and torrential rains; and rampant poverty compounded by major funding gaps from the international community and spillover from the depreciation of the Turkish lira. That being said, residents interviewed by COAR referred to the provision of food baskets and the availability of free-of-charge services such as water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) as incentives to stay.[11]Interview on 20 April 2022. In addition, Atma camp’s proximity to the Turkish border makes it relatively safe from any future attacks by the Syrian government and its allies.

Key challenges within the camp

The camp is managed by the Ministry of Local Administration and Services of the HTS-affiliated Syrian Salvation Government (SSG) which regulates NGOs’ work in the camp. Global Communities is the main humanitarian actor in the camp and runs the Green Hands Project,[12]The Green Hands Project website. whose main activities are in the WASH sector. The World Food Programme distributes monthly food baskets to camp residents via local partners, and education services are provided by some local organisations. Residents hold negative views towards the SSG governance of the camp, with interviewees criticising a lack of services and perceived interference in aid delivery. Relations with NGOs are mixed: some Atma residents report good relations with NGOs active in the camp (including NGOs that employ camp residents as staff), while other residents criticise NGOs for failing to meet needs.

Widespread poverty amid a lack of employment opportunities. The majority of camp residents are unemployed and rely on either remittances or aid. While interviewees said that the limited number of residents employed by NGOs receive “decent” salaries, many others rely on intermittent menial work or poorly-paid positions with the SSG and the camp management. The lack of job opportunities leads many camp residents to leave temporarily to work as seasonal harvesters and return after the harvest season. Most camp residents have no source of income and therefore cannot afford to move to nearby towns where they would be forced to cover their own expenses, including rent.

High population density and overcrowding within the camp and in the wider area. Camp residents interviewed noted severe overcrowding and a lack of sufficient infrastructure to support the population in the camp. Residents pointed to the poor condition of the roads, a lack of street lights, and an underdeveloped sewage system that is effectively an open, polluted river running through the camp and is highly susceptible to flooding. Population density is stressing available land and services throughout Idleb Governorate, which has grown in population from approximately 2.3 million in April 2018 to 2.8 million in May 2022.[13]Humanitarian Needs Assessment Programme.

Limited educational system. While public schools exist in northwest Syria and are accessible for Atma residents, they are overcrowded and underfunded. Private education has proliferated throughout northwest Syria to fill the gap; however, fees are often unaffordable for residents.

Lack of long-term, durable housing. Residents in Atma largely live in brick structures but without permanent, solid roofs, which are not permitted by camp authorities and landowners.

Prospects for return, resettlement, or reintegration

Without a sustained political settlement to the conflict, residents of Atma have few prospects of returning to their homes in Government of Syria territory. Interviewees reported that some residents, particularly older ones, had been smuggled back to their hometowns in order to check on and secure their properties when they have been at risk of confiscation by the Government of Syria. Because residents fled some of the most intense fighting and destruction of the conflict, however, most have nothing resembling a home to return to. Residents have instead turned to local integration to establish lives and livelihoods, renting property elsewhere in northwest Syria or buying small patches of land close to the camp to build houses. However, with the growth of the population throughout northwest Syria, land prices have increased, as have rents.

Several humanitarian organisations have resorted to transferring displaced people from various camps in Idleb governorate, including Atma, to prefabricated or brick houses within residential complexes commonly referred to as “villages”.[14]The Syria Report “On Syrian-Turkish Border Strip, Aid Groups Replace Tents with Alternative Housing,” 08 February 2022. These projects select their beneficiaries from the most vulnerable such as women-headed households with children. Several projects have been launched by the Turkish Red Crescent and Turkey’s Disaster and Emergency Management Authority (AFAD), the Qatar Red Crescent Society (QRCS), and various Syrian organisations relying on private donations:

- In March 2022, The Turkish Red Crescent handed over 50,000 newly built houses to displaced Syrians in the countryside of Idlib governorate, as part of a campaign launched by the Turkish Ministry of Interior in January 2020. The project aims to provide residences for more than 350,000 IDPs in Idleb governorate.[15]Anadolu Agency, “The Turkish Red Crescent is building 50,000 houses and handing them over to Idlib’s displaced (report),” 6 March 2022.

- In 2021, Watan Organization built two residential complexes in Idleb; the first containing 500 housing units and the second containing 3,100 units. These two projects host IDPs from six irregular camps exposed to floods.[16]Syria Direct, “Housing projects for the displaced in northwest Syria: deferred real estate problems,” 27 June 2021.

- Syrian NGO Molham Team has implemented several housing projects, including a project to construct 1,000 cement housing units in the village of Torlaha in Harim, Idleb. The Team also runs the ongoing “Until the Last Tent” campaign to raise funds for building cement housing units.[17]The Molham Team website, Until the Last Tent Project.

- In 2015, the Qatar Red Crescent launched a project aiming to build 2,200 mud brick houses in Idleb. The first stage of the project built 100 mud houses in Afes village near Saraqib.[18]Al-Sharq, “In pictures, the Qatar Red Crescent builds 2,200 homes for the displaced in Syria,” 12 July 2015.

Nevertheless, these housing projects pose several problems. The lack of available land for building means they can only host small numbers of the IDPs in northwest Syria, and such building is further increasing urban density in an already overcrowded region. Some aid actors cite HLP issues and demographic change as concerns preventing them from supporting such projects. Indeed, long-term land rights are likely the greatest impediment to such housing complexes becoming long-term settlement solutions. The complexes have been built under the auspices of the Syrian Salvation Government, outside of formal Government of Syria state planning processes. Should the Government of Syria return, there are no guarantees that the property claims of beneficiaries will be respected, potentially inviting further displacement concern.

Looking ahead

Atma camp residents were forcibly displaced after the Syrian Army and its allies captured their towns, and few are able to return in the absence of a resolution to Syria’s conflict, particularly amid the likelihood that their property has been either destroyed or confiscated. Residents interviewed highlighted a desire to move to Turkey or onwards to Europe should the opportunity arise. Otherwise, residents hope to earn enough money to buy a patch of increasingly scarce land in northwest Syria and build a home.

In the absence of mechanisms for return and resettlement, the efforts of humanitarian organisations have focused on improving camp conditions and on projects that grant camp residents temporary stability by building housing complexes,[19]ACU, “Housing Complexes In North-Western Syria,” April 2022. which seem to be the only available alternative to living in tents. Nevertheless, this type of project faces obstacles, including the lack of a legal authority to grant organisations the right to use public lands, as well as the inability of international donors to deal with de facto authorities or state-owned lands. As a result, such projects are mostly funded by private donations raised by local organisations.

Providing dignified shelters, as proposed through the recent “Action Plan for Dignified Shelter & Living Conditions in NW Syria”,[20]Shelter Cluster, “Action Plan for Dignified Shelter & Living Conditions in NW Syria,” 17 March 2022. offers considerations for semi-fixed shelters that will address some environmental and protections concerns of residents without providing permanent solutions.

2. Rukban Camp

Current Population: 7-10,000[21]Refugees International, “11 Years of War: The Humanitarian Impact of the Ongoing Conflict in Syria,”16 March 2022.

Peak Population: 85,000[22]UNHCR, “ Jordan Operational Update – December 2016”.

Founded: 2014

Location: Sabe Byar, Duma district, Rural Damascus Governorate

Cut off on all sides, Rukban camp is located within one of Syria’s most deeply politicised and inaccessible areas. Rukban camp sits on the Syrian-Jordanian border, at the southernmost desert reaches of Homs governorate, inside a 55-kilometre “deconfliction zone” around the nearby al-Tanf Garrison, where US forces operate with the support of local partner force, the opposition group Maghawir al-Thawra. Jordanian authorities have shut access to the camp from the south, and Syrian government forces have blockaded the outer perimeter of the 55-kilometre zone, which US forces prevent them from entering.[23]The World, “Blame game over aid leaves Syrian refugees stranded in desert ‘death’ camp,” by Shawn Carrié and Asmaa Al Omar, 11 March 2019. As a result, humanitarian access, food, medical supplies, livelihoods, and services are limited, if not altogether absent. Robust smuggling routes through the western Badia desert have been a lifeline for the camp since its formation in 2014,[24]The London School of Economics and Political Science, “Violence, Insecurity and the (Un)making of Rukban Camp,” by Suraina Pasha, 19 February 2018. although high prices have strained residents’ meagre remittance-based wages. The Syrian government’s decision to halt smuggling to the camp in February 2022, as it has done periodically in the past, has shut down the camp’s sole bakery. Remaining residents largely hail from government-held territory in Homs, Ar-Raqqa, and Deir-ez-Zor governorates. The majority of one-time residents have already left the camp due to dire humanitarian conditions exacerbated by the multi-sided blockade of the camp.[25]Reuters, “Russian ‘siege’ chokes Syrian camp in shadow of U.S. base” by Suleiman Al-Khalidi, 28 April, 2019. Those who return to areas of Syrian government control risk military conscription and reprisal by state security services, while those who remain in the camp endure extreme deprivation. The risks of return to government-held areas are especially immediate for local activists and members of opposition factions, including Maghawir al-Thawra.[26]Al-Monitor, “Nobody cares about us’: Syrians stuck at Rukban camp decry lack of testing,” by Elizabeth Hagedorn, 16 April 2020.

Key challenges within the camp

Situated in a no man’s land in the 55-kilometre “deconfliction zone”, there is no state or state-backed entity responsible for the management of Rukban camp. Disputes and conflicts in the camp are usually resolved on a clan or family basis, with residents turning to a committee responsible for civil administration composed of camp residents and dignitaries to resolve broader conflicts. Notably, there are also smaller committees to represent each of the hometowns of camp residents. Security and protection in the perimeter of the camp are maintained by the US partner force Maghawir al-Thawra.

Lack of access for aid actors. The overwhelming challenge complicating life in Rukban is the lack of humanitarian access, as entry is blocked on all sides and official aid deliveries have been restricted since the last UN convoy to the camp in September 2019. Residents therefore suffer a lack of food, healthcare, education, and social and legal services. Some residents have attempted to build livelihoods through small-scale farming, while others work with smugglers. Many earn livelihoods by joining the ranks of Maghawir al-Thawra.

Prospects for return, resettlement, or reintegration

The governments of Syria and Jordan have substantially reduced the size of Rukban by limiting access to the camp, compelling many residents to leave for Syrian government-held areas. The camp’s population of 85,000 at its peak in late 2016[27]UNHCR, “ Jordan Operational Update – December 2016”. has now diminished to between 7,000 and 10,000. Residents returning to Government of Syria areas have been detained, despite purported security clearances from the Syrian government.[28]The New Arab, “Baby born in besieged Syrian refugee camp ‘close to death’ as appeals for treatment are ignored,” 10 March 2022; SACD, “SACD confirms 174 Rukban returnees arrested by … Continue reading Residents interviewed said that return is in effect impossible without safety guarantees that would require coordination with Syrian intelligence services through local notables. In view of the barriers to return to Government of Syria areas, many of the camp’s residents have expressed a preference for relocation to northern Syria.[29]The National, “Rukban residents ask to be moved to northern Syria if US troops withdraw,” by Mina Aldroubi, 03 January 2019.

Return initiatives

In February 2019, the Russian Ministry of Defence and Syrian authorities announced the creation of two “humanitarian corridors” and temporary reception centres on the border of the 55-kilometre zone around al-Tanf to evacuate residents of the Rukban camp to government-held areas,[30]TASS Russian News Agency, “Corridors for refugees from Rukban camp open — Russia’s Defense Ministry,” 19 February 2019. urging the UN and SARC to join the operation.[31]TASS Russian News Agency, “Two humanitarian corridors for Syria’s Rukban refugee camp to be opened early on Feb 19” 16 February 2019. However, the plan did not offer formal security guarantees to address residents’ safety concerns.[32]Refugees International, “Civilians Imperiled: Humanitarian Implications of U.S. Policy Shifts in Syria,” 28 February 2019. The plan was announced following the release of a faulty UNHCR intention survey[33]UNHCR, “Critical needs for Syrian civilians in Rukban, solutions urgently needed,” 15 February 2019. that stated most residents of Rukban wanted to return home without referencing the “significant protection concerns” they also widely expressed.[34]Amnesty International, “Syria: Former refugees tortured, raped, disappeared after returning home,” 07 September 2021. These concerns were only addressed by OCHA almost two weeks later.[35]UNOCHA, “Briefing To The Security Council On The Humanitarian Situation In Syria,” 26 February 2019. Despite the lack of security guarantees, Russian authorities claimed in 2019 that over 13,000 people had left Rukban via these humanitarian corridors.[36]TASS Russian News Agency, “Over 200 refugees leave Syria’s Rukban camp in past day — Russian reconciliation center,” 30 May 2019.

A further UN and Syrian Arab Red Crescent (SARC) attempt to facilitate returns from the camp in September 2021 was cancelled when a group of camp residents obstructed a convoy that had arrived to “aid the voluntary departures of people from Rukban”.[37]Middle East Monitor, “Syria: UN denies trying to return refugees to regime territory,” 14 September 2021. A total of 88 individuals had registered with the UN to leave, but the plans to transfer the camp’s residents to Homs were leaked, resulting in Amnesty International urging the UN and SARC not to proceed, owing to the risk of persecution of returnees by the Syrian government.

Despite the limited success of these organised initiatives, the dire humanitarian situation in Rukban has forced a steady stream of residents to leave the camp and either return to Government of Syria areas or attempt to reach northern Syria via smuggling routes, and then to travel onwards to Turkey or elsewhere. Returnees to Government of Syria areas must reconcile their status with the Government of Syria, a process that does not immunise returnees against legal jeopardy. Options for smuggling to opposition areas in the country’s north are expensive and physically dangerous given the need to pass through Government of Syria-held territory and the eastern Badia desert, in which Islamic State (IS) remains a threat.

Looking ahead

There are limited prospects of return for those stuck in Rukban. The UN may have placed voluntary return on the table, but it has faced strong criticism for forcing residents to choose between enduring the continued desperation of Rukban or rolling the dice with a notoriously vindictive Syrian Government. No party is in a position to secure anything like the guarantees that would supply residents with confidence in their onward protection upon return.[38]The UN conceded as much with its ‘repatriation’ programme, stating that ‘the security and safety of individuals’ rests with the Syrian Government. That thousands of people would sooner suffer the indignities of Rukban than return at a time of relative calm in much of Syria is as strong an indication as any that, for many camp residents, return is not an option.

Local integration is similarly impossible given that there is very little settlement in Syria’s southern desert and, additionally, the long-term safety of the population in the deconfliction zone is contingent on a continued US presence at al-Tanf. Syria’s north has been posited as offering some refuge, but authorities across the region may be reluctant to accept Rukban IDPs given their own insurmountable displacement challenges. Such a proposal could also require a comprehensive package of resettlement support and fraught negotiations with the Government of Syria to permit the residents of Rukban to transit through its territory, and also likely require the US to abandon al-Tanf, which it appears unwilling to do.

With few options for relocation, and until political conditions evolve to allow for some negotiated breakthrough, attention must therefore turn to long-term humanitarian support and the delivery of aid and commercial goods to the camp. On 9 June, a commercial shipment entered Rukban from Jordan carrying flour, oil, sugar, bulgur and tea. Although this shipment was apparently delivered by a trader for sale and not as humanitarian aid, this nonetheless marked the first cross-border delivery of goods to the camp since 2018.[39]Middle East Eye, “Rare food convoy to camp on Syria-Jordan border signals shift in Amman policy,” 19 June 2022. The Jordanian government has been steadfast in its refusal to countenance further refugee intake from Rukban or otherwise assume responsibility for the camp; nevertheless, there may be opportunities to advocate with the Jordanian authorities to permit further deliveries of aid or commercial goods to the camp.

Cross-line aid delivery from Government of Syria areas remains the most sustainable solution to the humanitarian crisis in Rukban, yet this has previously been impossible to arrange on any regular basis. Nevertheless, both Damascus and Moscow have been keen on encouraging cross-line aid delivery elsewhere in the country, principally in Syria’s northwest but also its northeast. Rukban may present another opportunity to coordinate cross-line aid.

3. Hole Camp

Current Population: 55,116

Peak Population: 73,520[40]REACH, “Camp Profile: Al Hol Al-Hasakeh governorate, Syria April-May 2019”.

Founded: 1991; 2015 (under SDF control)

Location: The southern outskirts of Hole town in eastern Al-Hasakeh Governorate, northeastern Syria.

Hole camp, located in the eponymous Hole sub-district of Al-Hasakeh governorate, is the largest camp in northeast Syria, with around 55,000 residents as of June 2022.[41]UNHCR, Protection Cluster, “Syria Protection Sector Update: Al-Hol Camp, June 2022”. Originally established for Iraqi refugees in early 1991 during the First Gulf War, Hole camp came under the control of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in November 2015. Its population grew as people fled communities in Deir-ez-Zor and Ar-Raqqa governorates during the battle against Islamic State (IS). In March 2019, with the fall of IS’ last enclave, Al Bagouz, a distinct final wave of displacement occurred as civilians — including family members of IS fighters — exited the final IS pocket and were relocated to the camp. Today, roughly one-third of the camp’s population is Syrian, half are Iraqi, and the rest other foreign nationals.[42]UNHCR, Protection Cluster, “Syria Protection Sector Update: Al-Hol Camp, June 2022”. Women and children account for 94 percent of the camp population.[43]MSF, “Syria: MSF teams treat women for gunshot wounds amid violence and unrest in Al Hol camp,” 30 September 2019. The camp houses individuals with varying degrees of ties to the IS apparatus that ruled territory in Syria and Iraq, but also thousands of individuals with no IS association at all who flocked to the camp fleeing conflict. Humanitarian conditions in the camp are dire, contributing to a sense of grievance and perceptions of collective punishment among residents. Services are limited and critically overstretched, and shelter is inadequate.[44]Save the Children, “When am I Going to Start to Live? The urgent need to repatriate foreign children trapped in Al Hol and Roj Camps,” 27 September 2021. Critical gaps exist across all sectors, especially WASH, health, nutrition, education, and protection.[45]Save the Children, “When am I Going to Start to Live? The urgent need to repatriate foreign children trapped in Al Hol and Roj Camps,” 27 September 2021.

Key challenges within the camp

The camp is under the control of the Asayish, the Autonomous Administration’s internal security force, which residents view as more akin to prison guards than a civilian camp authority. Few residents expressed confidence in the way in which the camp is managed, and popular relations with NGOs operating in Hole are mixed. Some residents dismiss the organisations’ services as poor and allege that the camp’s continued maintenance primarily serves the needs of the NGO sector, with little benefit trickling down to residents. In this context, three key challenges are noted.

Poor security conditions and sense of ill-treatment by camp authorities. Security conditions in the camp are precarious and compounded by perceived ill treatment by the SDF, leaving many, particularly children, vulnerable to radicalisation in the camp.[46]New York Times, “ISIS Fighters’ Children Are Growing Up in a Desert Camp. What Will They Become?” 19 July 2022. The SDF lacks a clear approach to identifying and isolating radical camp residents, thus compounding the consequences of its failure to provide adequate protection and security across all zones of the camp. Some have accused the SDF or foreign fighters in Idleb governorate of trafficking children from the camp for military recruitment purposes.[47]Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Monitor, “The “SDF” Kidnapped Dozens Of Children And Young Men In Eastern Syria,”17 September 2019. (Arabic) and Al-Quds Al-Arabi, “Kurdish Fighters … Continue reading A lack of comprehensive safeguarding and protection increases the risk of kidnapping, trafficking, and recruitment among the camp’s children.

Dire humanitarian situation. Services in Hole camp are chronically inadequate,[48]TRT World, “Syria’s notorious Al Hol Camp is ‘on the brink’ of a humanitarian disaster,” 01 October 2019. contributing to residents’ sense of grievance and collective punishment. Residents highlighted limited education, training, and work opportunities. Opportunities exist to work with NGOs, but those who take them face the risk of targeting by IS elements or sympathisers.

Lack of repatriation of foreign residents. Foreign residents make up approximately 70 percent of Hole camp’s population, and the slow pace of repatriation initiatives presents a burden to the SDF security and management of the camp. Iraqi authorities have reportedly repatriated 2,500 Iraqis from the Hole camp, but an estimated 28,000 remain — approximately 50 percent of the camp’s population. Iraqi officials attribute the slow pace of repatriation to the process of vetting returnees. They must also contend, however, with local Iraqi communities’ resistance to receiving families with perceived IS affiliations (so-called “IS families”).[49]United Nations Iraq, “Visit to Al-Hol camp in northeastern Syria,” 6 June 2022; Washington Post, “After years in ISIS prison camp, they now face an uncertain welcome home,” 5 July 2022; … Continue reading For other foreign nationals, home countries have generally been reluctant to repatriate citizens whom they consider a national security threat and a political liability, particularly amid rising nativist sentiment in many countries of origin.[50]BBC News, “Shamima Begum cannot return to UK, Supreme Court rules,” 26 February 2021. Foreign government’s disinclination to officially recognise the Autonomous Administration is a further complicating factor for foreign repatriation.

Prospects for return, resettlement, or reintegration

While the Autonomous Administration has reiterated its aim of emptying Hole of its residents — a goal notionally supported by the international community — issues stemming from the residents’ places of origin have complicated return efforts.

Generally seen as a security concern due to their perceived IS affiliations, there are few presently viable options for the release and return of Syrians in Hole camp. The SDF provides two formal release mechanisms for Syrians in the camp: tribal sponsorship, through which residents are released with security guarantees by tribes in their hometowns; and the “SDF model”, whereby residents are vetted and assessed by camp authorities and then released to the civil administrations in their hometowns. Both processes are allegedly marred by corruption, are applicable only to people originating from areas under SDF control, and are insufficiently linked to dedicated reintegration programming.[51]For more on these release mechanisms, see COAR Global (2021) “Mapping and Assessing Release and Reintegration Models from NE Syria Camps”. Stigmatisation and other anticipated socio-economic consequences are powerful disincentives to leaving the camp.[52]Al-Monitor, “Syrians returning from Al-Hol camp stigmatised over IS ties,” 15 June 2022. A number of pivotal issues remain for Syrians looking to leave Hole camp, including housing, land, and property (HLP) documentation; the status of inherited properties; return to former places of work; and civil records and documentation of marriage, deaths, and births. Indeed, while expressing strong desires to leave the camp, residents of Hole camp interviewed for this research do not know what will await them if they are able to leave.

In the absence of formal ways to leave the camp, residents have escaped from Hole camp through camp guards, workers, and networks of smugglers coordinating with IS or foreign fighters in Idleb, or the SDF.[53]Daraj, “Syria: Smuggling Out of the Hell of Al-Hol,” 26 May 2021. Smuggling can cost between $8,000-$15,000, which is sometimes fundraised through digital platforms, and residents say that pricing, methods, and individuals involved in facilitation are well-known.

Looking ahead

The challenges of Hole camp admit of no easy solutions. Residents interviewed described Hole camp as a prison and a “ticking time bomb” and were pessimistic about prospects for the future. Those with family outside the camp expressed the desire to leave and return to their hometowns, although they are unsure exactly what this would entail and described it as going into the “unknown”. Without permission to leave, they are held in place and at risk of growing increasingly resentful and aggrieved.

As is implicit in the efforts of donor governments and aid agencies, the return of IDPs and the repatriation of foreign residents is the preferred solution to bring about just results for the camp population and minimise the risks to the local area, the region, and the international community. In the narrow case of camp residents from within Syria, the existing mechanisms of return have been exhausted, and returns have slowed after some movement in 2020 and 2021. For Syrians who remain in Hole, return will be possible only by improving information related to their intended destinations and addressing their substantial socio-economic, protection, and reintegration concerns. For foreign nationals, matters of basic coordination with local authorities in their home countries, including all-important concerns over legal accountability and community reconciliation, remain paramount. Without progress on these files, a significant portion of the population will remain in limbo for the foreseeable future.[54]UNDP, “UNDP Iraq supports the Iraqi Government to prepare communities for reintegration of returnees from Al-Hol Camp,” 18 August 2021.

4. Deir Ballut and Muhammadiya Camp

Current Population: 6,288[55]OCHA, “IDP Sites Integrated Monitoring Matrix (ISIMM),” May 2022.

Peak Population: 6,288

Founded: April 2018

Location: Deir Ballut, Jandairis, Afrin, Aleppo Governorate

The Deir Ballut and Muhammadiya camp, built on public land near Jandairis in the countryside of Afrin, was established in April 2018 by AFAD and the Turkish Red Crescent, immediately after the end of Operation Olive Branch and in conjunction with the evacuation agreement that took place in Yarmouk camp on 21 May 2018.[56]The Syrian government took control of Yarmouk camp on 21 May 2018 following an agreement with opposition military factions. The agreement led to the forced evacuation to northern Syria of those who … Continue reading Most camp residents are Palestinians and Syrians from the occupied Golan Heights who were living in the Yarmouk camp and towns south of Damascus, impoverished areas that had been largely Islamic State-held and had been besieged and bombarded for years by the Syrian government and its allies. The camp’s Turkish management, AFAD, maintains security and provides essential services to residents such as bread, basic health care, water, and education. These conditions, although far from ideal, still make the camp a better place to live than many other camps in Syria’s northwest. Nevertheless, the camp is highly susceptible to flooding during periods of heavy rainfall, with many residents living in tents that do not offer protection from extreme weather. Most camp residents lost everything they owned when they were displaced and therefore cannot afford to leave and pay rent, let alone buy or build a house in nearby towns. Those who have left and been granted permission by Syrian National Army factions to live in villages elsewhere in Afrin remain at the mercy of these factions for access to property and employment. In many cases, they occupy houses or property abandoned by the region’s predominantly Kurdish local residents during Turkey’s Olive Branch operation, thus perpetuating a cycle of serial displacement and dispossession among multiple Syrian populations.

Key challenges within the camp

The camp is managed by AFAD, while the civilian police of the Syrian Interim Government, based in Jandairis, are responsible for security. Interviewed residents report varying relationships with the camp management, depending on personal relationships with employees in charge, and say that any tensions typically relate to aid distribution in the camp. While initially camp residents were not permitted to build structures such as walls and sewage systems, and those built by residents were destroyed by the camp authorities,[57]Enab Baladi, “Politics of Smuggling in Deir Ballut camp in Aleppo countryside,” 28 October 2018. rules were relaxed in 2019 and now residents can build walled residences — although permanent roofs remain banned. Additional challenges remain.

Limited work availability and poor pay. Many of the men within the camp reportedly work with Turkish-backed armed factions, which pay low salaries.

Poor humanitarian situation. While the camp is considered to have better conditions than others in the region, as it has a management system that provides basic services such as a sewage system, a health centre, and a school, living conditions remain harsh due to the lack of access to the electrical grid, scarce water supplies, and suboptimal access to health care.

Location susceptible to flooding. The camp’s position in a valley makes it highly susceptible to flooding in the event of heavy rainfall.[58]Syria Direct, “Flooded tents, unresponsive authorities at Turkish-run displacement camp bracing for first winter,” 14 November 2018. Residents’ requests to move the camp to a location that is safer from floods have gone unheard. Residents largely live in tents or in walled residences without permanent roofs, which do not fully protect from the heat in the summer and from rain and wind in the winter.

Prospects for return, resettlement, or reintegration

Many families who first arrived in the camp left it within a few weeks, with the richer families resettling in larger towns, and the poorer families in small villages in the Afrin region. These smaller villages are relatively empty of their original populations, who either lived in Aleppo city or other larger towns and only visited in the summer, or fled following the 2018 Turkish “Olive Branch” operation due to their affiliation with the YPG/PYD/PKK and fear of retribution. Hard to reach and lacking in services and infrastructure, the villages are now largely inhabited by IDPs.

It is important to note that resettling in abandoned houses in these villages requires permission from the rebel factions who control the region. For example, the majority of those from the eastern Qalamoun town of Dumeir, who were the first to arrive in the camp soon after it was built in 2018, left after six weeks and resettled in a remote village nearby, relying on rebel leaders among them to negotiate with the factions in control of Afrin. However, as most villages are now already occupied by IDPs, it is difficult for others to find accommodation.

Looking ahead

Similar to Atma camp, the vast majority of residents of Deir Ballut and Muhammadiya camp were forcibly displaced from their homes in the southern neighbourhoods of Damascus and Damascus countryside in surrender and evacuation deals. Therefore, they likely cannot return in the absence of a resolution to Syria’s conflict. There are no projects that specifically target Deir Ballut and Muhammadiya camp residents with return, reintegration, or resettlement.

Demographic concerns related to the displaced populations of Afrin are of paramount importance. Despite the unwillingness of most Western donors to implement in Afrin owing to these issues, IDPs who have relocated there of their own accord will face uncertain futures. Because displaced persons rely on agreements with local military factions for permission to settle, they lack permissions from legal authorities to inhabit the land and could face further displacement should territorial control shift. While it is too late to prevent such areas from being re-settled, the case highlights the potential downstream consequences of a failure to provide sustainable alternatives.

Interviewees still resident in the camp are at the mercy of AFAD decisions and have no sense of a clear plan for the future of the camp. A lack of job opportunities mean they are unable to leave the camp, where at least they are provided with the essentials of food, water, shelter, and security, interviewees say they intend to wait in the camp until a decision is made by AFAD — either to move them to a different camp, to move them to residential complexes elsewhere, or to turn the camp itself into residential complexes. Importantly, interviewees highlighted the desire to stay in the camp as long as they were together with family and neighbours with whom they were displaced.

Conclusion

For most of those living in Syria’s displacement camps, return to hometowns and previous lives is impossible. Aid actors thus face the prospect of dealing with long-term displacement, requiring adaptation to sustainable service delivery into the future. With the conflict largely frozen and a political solution no closer in sight, new approaches that go beyond the delivery of basic humanitarian aid will be needed to provide the residents of camps not only with the essentials of food and water, but opportunities to build homes, livelihoods, and provide a future for their children.

References[+]