Kharkiv City

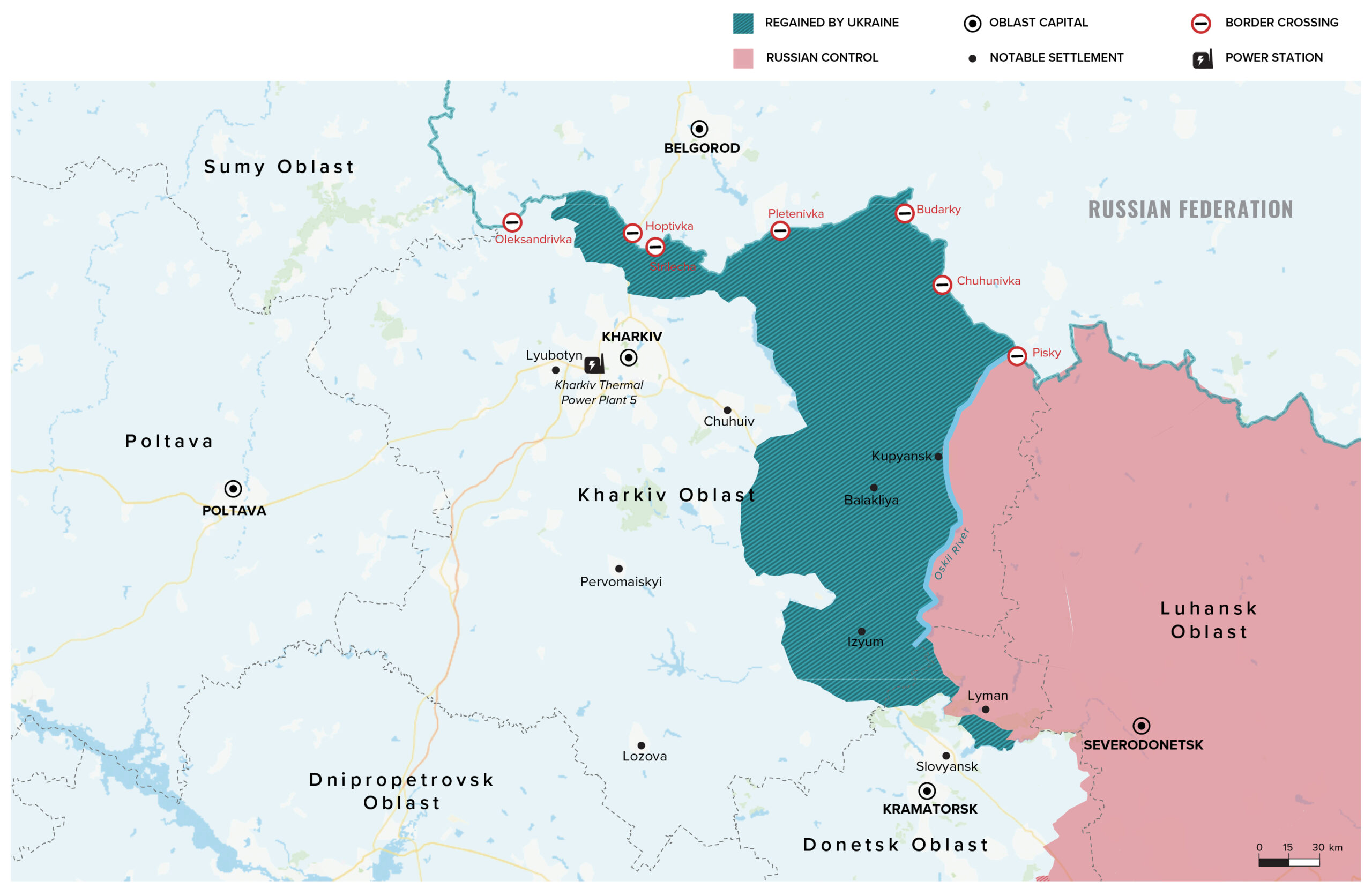

The counteroffensive launched by the Ukrainian armed forces in early September has completely transformed daily life in Kharkiv oblast. Prior to 6 Sept, Russian forces controlled 32% of the region; as of mid-Sept, this number had shrunk to 6%. Formerly occupied cities such as Izyum, Balakliya and Kupyansk have been liberated, with Russian troops leaving a complex humanitarian situation in their wake. Ukrainian authorities are now faced with the challenge of demining large stretches of territory, restoring basic infrastructure and services, and forging a robust approach to transitional justice in the liberated areas.

Geography and Background

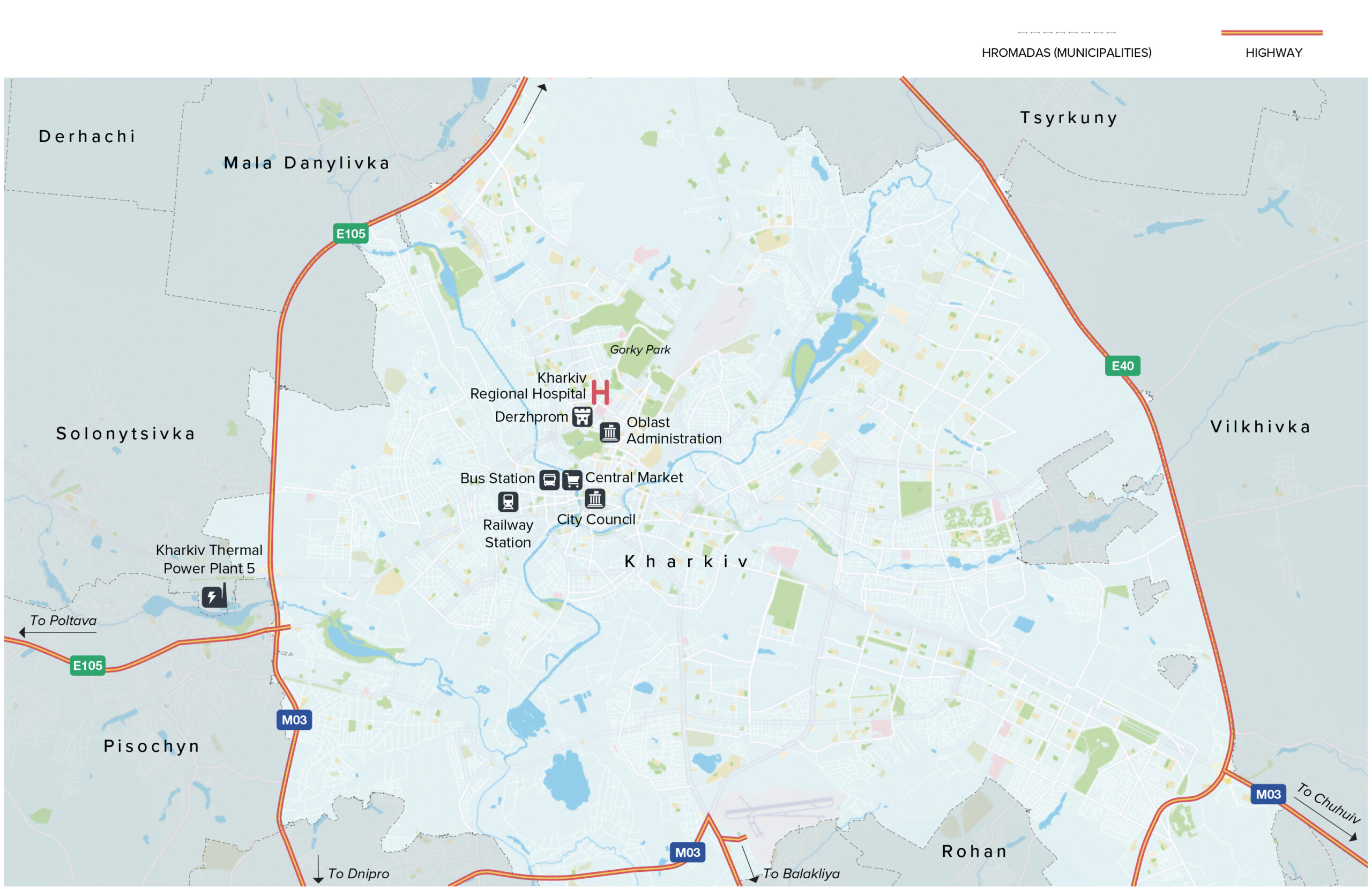

Kharkiv oblast is located in eastern Ukraine and is the country’s third-most populous region, with a 2021 population of over 2.63 million. It is bordered by Sumy oblast to the northwest, Poltava oblast to the south, Dnipropetrovsk oblast to the southwest, Donetsk oblast to the southeast and Luhansk oblast to the east, as well as Russia’s Belgorod oblast to the north. Kharkiv city, the regional capital and one-time capital of Soviet Ukraine, is Ukraine’s second largest city (2021 pop. approximately 1.43 million) and a major industrial, educational, and cultural hub. It hosts the famous Malyshev factory, which produces mining, agricultural and military equipment, and many other facilities that manufacture electronics, turbines for power generators, aircraft parts and components for nuclear plants. Notable Kharkiv oblast cities and towns include Izyum, Chuhuiv, Balakliya, Lozova, Kupyansk and Pervomaiskyi. As of mid-September, the Oskil river in the region’s east divides Ukrainian and Russian positions.

Status of conflict

While much of the region has been occupied since the early months of the war, including positions within 20km of Kharkiv city, the recent Ukrainian counter-offensive has pushed Russian troops to the eastern bank of the Oskil river, as well as to the Russian border north of Kharkiv city. Major liberated urban centers include Balakliya (8 Sept), Izyum (9 Sept) and Kupyansk (10 Sept). Russian troops present were likely surprised by the campaign, with some soldiers reportedly fleeing their posts prior as Ukrainian ones drew near. While Ukrainian troops have slowed their advance, they have begun crossing the Oskil river, which Russian troops have been using as a natural barrier. On 14 Sept, Deputy Minister of Defense Hanna Maliar announced that approximately 150 thousand residents living in 8500 square km of land had been liberated. Over 420 settlements have returned to Ukrainian control.

Kharkiv Oblast

Source: Liveuamap.com

Conflict related damage

Kharkiv city has suffered massive damage from Russian air and artillery strikes, and – over 400 buildings are thought to be beyond repair. As noted above, an infamous strike on 11 Sept damaged Kharkiv Heat and Power Plant #5 in the capital’s Kholodnohirskyi neighborhood, one of the country’s largest sources of energy. This led to blackouts across Kharkiv, Donetsk, Poltava, Zaporizhzhia, Dnipropetrovsk and Sumy oblasts, with the plant fully brought back online only on 17 Sept. Other targets include residential buildings, shopping centers, roads and bridges. Severely damaged neighborhoods in Kharkiv city include north and northeastern locales like Saltivskyi, Kholodnohirskyi and Selyshche Zhukovskoho, as well as parts of central Kharkiv city like Freedom Square and main thoroughfare Sumska Street. Many educational facilities in the oblast, including both schools and universities, have been damaged beyond repair, forcing local students to study online (see our upcoming RFI on schooling).

Outside of Kharkiv city, towns and villages in Chuhuiv, Izyum and Bohodukhiv districts have been damaged by strikes and ground combat. Water and power lines across the oblast, particularly in the north and east, have been hit, although these services generally operate uninterrupted, with the exception of the outages following the 11 Sept strike. Loss of life in the formerly occupied territories is still being calculated, though early signals are grim: approximately 450 graves in Izyum are currently being investigated while Izyum municipal deputy Maksim Strelnikov has stated that over 1000 of the city’s civilians died during the occupation.

Needs and Challenges

Key challenges

The primary challenges facing Kharkiv oblast are: a) dealing with the realities of deoccupation, which include establishing law and order, enacting transitional justice regarding alleged collaboration, documenting war crimes, caring for a traumatized populace and exhuming both individual and mass graves; b) providing safety to Kharkiv city and oblast residents who remain vulnerable to Russian strikes and leftover mines; c) restoring key infrastructure, including power lines and plants, residential buildings and regional transportation links; d) preparing for winter, which includes rebuilding damaged buildings and natural gas lines as well as making solid fuel and stoves more accessible for the populace; and e) providing economic support for residents affected by unemployment and inflation.

Deoccupation and reconstruction

Following the Russian retreat from most of Kharkiv oblast, global attention has been focused on civilian deaths and other potential war crimes. As of mid-Sept, approximately 250 war crimes purportedly committed in the region have been documented and registered. Alleged torture chambers have been found in deoccupied cities, and hundreds of graves were discovered outside of Izyum. As many bodies have yet to be identified, it is difficult to determine how many are civilians – there is evidence, however, that some were tortured or castrated before their deaths. Multiple sources on the ground note that a number of deaths in the occupied territories were caused by a lack of access to medicine, suggesting an immediate need for medical aid to newly-liberated areas.

Ukrainian state bodies are currently working to restore key infrastructure in liberated cities and villages. Emergency services clear rubble and perform search and rescue missions, while Kharkivoblenergo staff are repairing power lines and restoring electricity. Gas lines are also being restored, particularly in Izyum, which is currently without gas and with little electricity. This work is risky due to mines; an electrical foreman, for example, was killed by a detonation in Balakliya district. Key services like mobile medical units, policing, mail delivery, pensions and other social payments and Ukrainian-language media have already started back up. The Kyivstar phone network is slowly being reconnected, though many locations still lack mobile internet, and Starlink units are being distributed to help provide immediate access to social payments. Train lines are gradually resuming service, such as Derhachi-Kharkiv-Chuhuiv and Kharkiv-Balakliya, with tests underway for Kharkiv-Izyum.

Another major aspect of deoccupation involves identifying and punishing the alleged accomplices of the occupiers, as well as Russian troops or public servants who did not manage to evacuate. The State Bureau of Investigation claims that some Russian soldiers, hiding among the local population, have been detained. As of 21 September, the Kharkiv oblast prosecutor says his agency is looking into over 400 cases of potential cooperation with the occupiers, falling under three statutes – “treason,” “collaboration,” and “aiding the aggressor state.” Among those under investigation are the mayors of Kupyansk, Vovchansk, and Balakliya, along with numerous municipal leaders, public servants, and law enforcement officers. On 15 September the Security Service of Ukraine stated that it had performed “in-depth checks” of around 7000 people in the liberated territories, although this number has likely grown substantially since. There have also been unconfirmed reports of the apprehension of Russian school teachers recruited by the occupation administrations.

While some collaborators, including the mayors mentioned, made their positions public, others will take more work to identify. According to various open-source reports, investigators use administrative records left behind by occupation officials, including tax documents and lists of school staff or police personnel. These documents, naturally, do not shed light on the circumstances under which a person came to cooperate with the de facto administrations – i.e. whether they did so willingly or under duress. It is unclear how authorities plan to uncover any mitigating circumstances that might lessen penalties, or how they would define such circumstances. Moreover, it is not clear how broadly collaboration will be defined – whether, for example, doctors who treated Russian soldiers, recipients of Russian humanitarian aid, or people who had sexual contact with occupiers, will face penalties. As for any Russian teachers who may be apprehended, Deputy Prime Minister Iryna Vereshchuk has declared they will not be treated as POWs, i.e. be ineligible for prisoner exchanges.

Security

Ongoing strikes throughout Kharkiv oblast endanger the lives and health of residents. One local source in Kharkiv city says that “there are visibly less people on the streets, and many try not to leave home unnecessarily.” Another claims that there is a lack of dedicated bomb shelters in the city, leaving many without options when missiles or shells hit the capital. As of mid-Sept, about 250 hectares of land (and sometimes bridges) across Kharkiv oblast have been de-mined, though sappers and civilians have been killed after detonating mines. Police provide for public safety, with new squads reportedly “restoring order” in freshly liberated areas like Balakliya, Kupyansk, Izyum, Zolochiv, Lyptsi and Vovchansk (see “Deoccupation” above). Other sources claim that, in newly liberated and contested areas near the front line, “some [law enforcement] services are difficult to provide or are even nonexistent.” Elsewhere in the oblast, locals note an increased military and police presence on the streets, which they say has led to a drop in crime compared to before the invasion.

Basic services and commodity availability

Apart from in newly-liberated areas, locals say that most stores carry amounts of food, hygiene and household products comparable to pre-war levels, though some sources (especially in towns outside of Kharkiv city, like Lozova) mention that prices increased sharply in the early months of the war and have not fallen. To save money, many try to shop in bulk or rely partly on home-grown produce, per local sources. Fuel is available at all gas stations, though not all stations are operational. Medication is widely available other than in the newly-liberated areas, though specialized medications may be hard to come by. As mentioned above, there is a grave shortage of medication in the occupied territories, meaning that these areas will require immediate delivery of medical supplies upon liberation. Public services like garbage collection and street cleaning are also being restored in the liberated areas, though issues with water and gas mains continue as a result of air strikes.

Livelihoods and personal funds

Local sources report that households across the region are under economic pressure: salaries have dropped, major businesses (especially IT companies) have relocated from Kharkiv city to central and western Ukraine, smaller businesses (especially restaurants) have closed, and labor migration to Russia has stopped. Many businesses have reportedly laid off workers and refuse to make new hires, though new positions related to aid provision have opened up. There is also the matter of business owners in liberated territories who remained open during the occupation; this likely required paying Russian taxes, which may be seen as collaboration. Per one local source: “the majority [of unemployed residents] survive on humanitarian aid and social payments.” Receiving subsidies requires an internet connection, making restoring connectivity in liberated areas a major priority.

Winterization

Reinforcing findings compiled in our earlier RFI on preparations for the winter, local sources describe readily available materials for minor winterization preparations, such as film for covering windows, but materials for rebuilding damaged doors and walls are reportedly scarce and 1.5-2 times more expensive. Moderately damaged buildings are being restored quickly, though locals complain that support to private citizens looking to winterize their apartments or private homes may be inadequate. Key informants note that the lack of affordable heating has led many residents to build or purchase homemade potbelly stoves, though solid fuel has also proven scarce or costly. Local officials have also begun constructing mobile boilers to be deployed during winter. There are also plans to provide hospitals and other institutions with additional generators in case of power outages.

Movement, displacement, and evacuation

Other than curfew (22:00-6:00), Kharkiv oblast residents experience no restrictions on movement in longtime Ukrainian-controlled territories – regulations concerning movement in newly liberated territories is not yet clear. Transit within the oblast capital is occasionally interrupted by air strikes, and transportation to newly liberated areas is still being restored (see above). Vereshchuk has advised residents not to return to newly-liberated areas yet due to security concerns. People fleeing the oblast’s combat zones often live in dormitories in Kharkiv city, or, if none are available, in the metro stations converted to bomb shelters. IDPs may be subject to strict checks by security services and at checkpoints, especially if they are registered to addresses in the so-called ‘Luhansk and Donetsk People’s Republics’ (‘L/DPR’) without having previously held IDP status. Meanwhile, local sources note that many Kharkiv city residents have relocated from the northern and eastern neighborhoods to the south, often staying with friends or relatives. Evacuation from the oblast to other parts of the country is ongoing, with 1500 evacuees recorded the week of 11 Sept.

Area Response

Key aid and civil society actors

International actors providing aid in Kharkiv oblast include Doctors Without Borders (mobile clinics), People in Need (bus donations, hygiene kits), and the International Committee of the Red Cross (food and hygiene kits, including in newly-liberated areas) among others. Ukrainian NGOs include the Kharkiv Red Cross (medicine, food/hygiene kits), Caritas Kharkiv (food, medicine, legal aid), Daruy Dobro (food, medicine, ammunition), Nova Mriya (food), Akvarena (food/hygiene kits), Ukraine SOS (food kits, evacuation), Unbreakable Kharkiv (evacuation, medicine, military supplies) and the Station Humanitarian Hub (food/hygiene kits, medicine).

Local authorities

Kharkiv’s military administration (Facebook, Telegram) is led by Oleh Synyehubov, who served as governor of Poltava oblast until December 2021; he provides regular updates on the region on his social media pages (Facebook, Telegram). The mayor of Kharkiv city is Ihor Terekhov (Facebook, Telegram).

Information Environment

Traditional media

Local television channels include Sulspilne Kharkiv (Facebook, YouTube, Telegram, Instagram), ATN Kharkiv (Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, Twitter), NTN Kharkiv (Facebook, YouTube) and Obyektiv/Simon (Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, Twitter). Radio stations include Ukrainian Radio Kharkiv (RadioBox), Radio Bayraktar (Top Radio) and Radio Pyatnitsa Kharkiv (Top Radio). Popular newspapers and online portals include Kharkiv Izvestia (Facebook, YouTube, Telegram, Instagram, Viber), Evening Kharkiv (Facebook, Twitter, YouTube) and Holovne in Ukraine (Facebook, Twitter).

Social media

- Trukha Kharkiv (Telegram, YouTube, TikTok)

- Kharkiv Life (Telegram)

- Khu*viy Kharkiv (Telegram, Instagram, Facebook)

- Kharkiv Blog (Instagram)

- Kharkiv Live (Instagram)

- Kharkiv Hero City (Telegram)

- Kharkiv Main (Telegram)

- Identifying collaborators: Kharkiv Traitors (Telegram)

- Pro-Russian: Kharkov Z (Telegram)

- Pro-Russian: Kharkiv Antifascists (Telegram)

Public Attitudes, Perceptions and Rumors

Conversations with locals across the oblast reveal a striking range of political sympathies and resentments. In Kharkiv city and western parts of the region, locals generally appear to express faith in Ukraine’s eventual victory and support for the military, mixed with fatigue at shelling and air strikes. Some predict that they will never again feel truly safe – a fear that is likely shaped by Kharkiv’s location on the Russian border. One key informant in Kharkiv city said that while he believed the entire oblast would be liberated soon, “even if the war ends tomorrow, I’ll still be afraid because this can happen all over again.”

The mood in recently liberated territories seems to be substantially bleaker than in areas previously under government control. Some are unsure whether Ukraine or Russia will win out, preferring not to disclose their true opinions until the final outcome becomes clear. Others refuse to talk to outsiders and chase them off their property. One young person expressed regret over the frontline’s sudden shift, reportedly telling a key informant:

You understand, everyone abandoned us … We were living on scraps and food out of jars. And then just as life was settling down and I’d started [school] in Kupyansk, the Ukrainians came and I had to drop out. I had two days of studying and that was it.

Concerns over the increased combat accompanying liberation may contribute to local ambivalence or even outright hostility towards the army – and, justifiably or not, encourage pro-Russian sentiment. For example, residents in the village of Blahodativka, near Kupyansk, described having been “passed over” by the Russian invaders, who left them in relative peace. One said he felt like “our war started two weeks ago” during the Ukrainian counter-offensive. “We had to sit in basements because they [Ukrainians] came,” he said. Contrasting views on the occupation may be present even within single households: one key informant mentioned having a woman in a recently-liberated village tell them that conditions under the Russians had been “basically tolerable”– only to be interrupted by her son-in-law who reminded her, visibly upset, that he had been forcibly imprisoned. Acknowledging these nuances will be key for ongoing efforts to reintegrate the territories, develop social cohesion and eventually encourage dialogue and reconciliation.