Current Situation

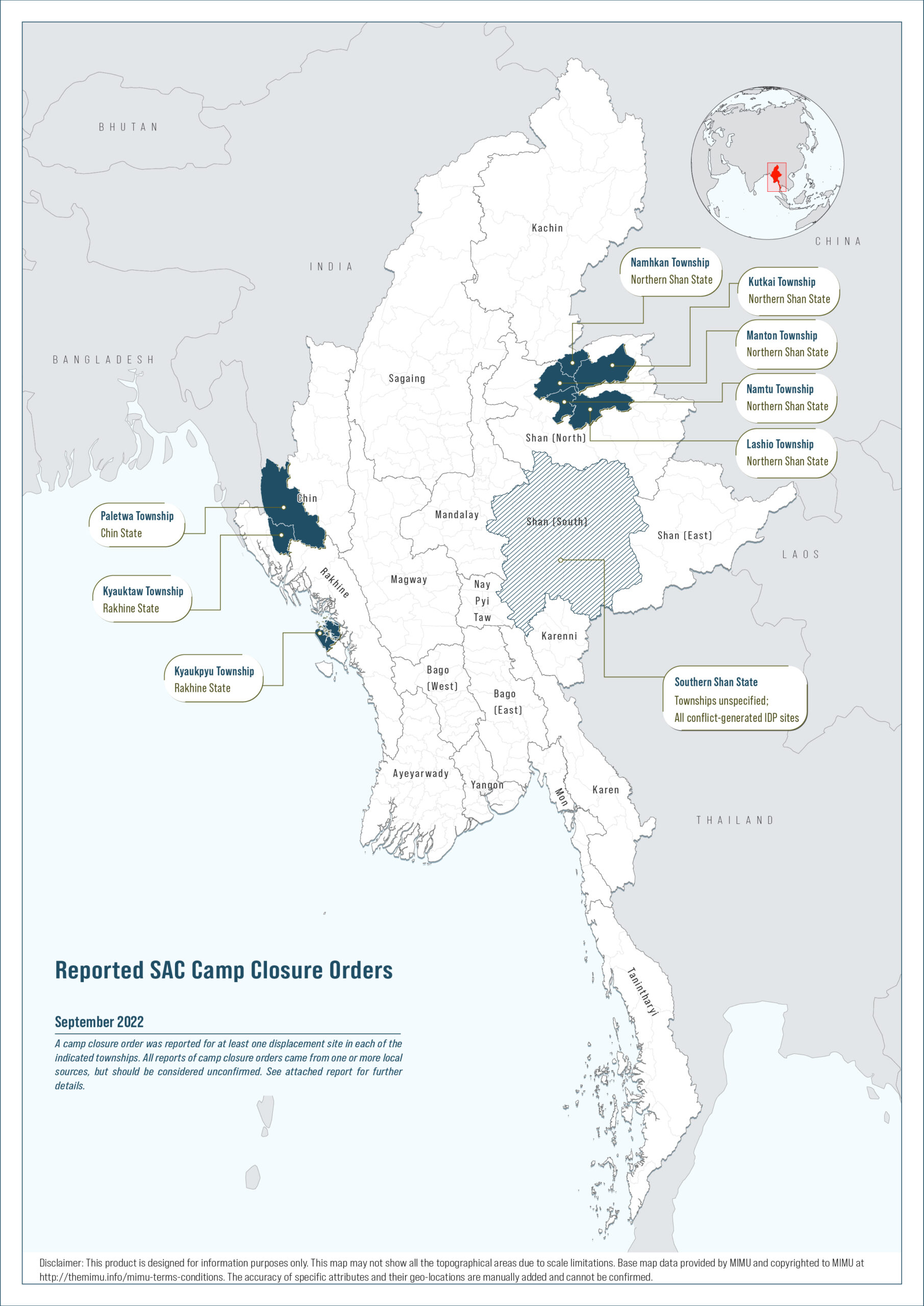

Reports emerging across Myanmar indicate that, in early September, the State Administration Council (SAC) ordered IDPs from some townships in Rakhine, Chin, and Shan States to leave their camps and return to their areas of origin. One source who spoke to this analytical unit said this order is rumoured to be intended for all IDP camps in Myanmar.[1] However, this rumour has not been confirmed, and many of the details surrounding these proposed camp closures remain unclear. While the closure dates appear to be imminent — perhaps even this month — it is unknown whether or how the SAC plans to support communities in this process.

Communities reported concerns to this analytical unit that the SAC is weaponising camp closures and returns.[2] Some community members in Rakhine State who spoke to this analytical unit speculated that the SAC might be concerned that the United League of Arakan/Arakan Army (ULA/AA) could receive (or intercept) support channelled via IDP camps — a concern which could presumably translate to other areas of ethnic resistance as well.[3] Other community members spoke of fears that camp closures are designed to push civilians back into conflict zones, in an effort to make it more difficult for armed groups to operate militarily without putting civilians at risk and undermining community support. Some of these closures — such as the ones in Southern Shan State — may also be related to negotiations around territorial control between the SAC and ethnic armed organisations (EAOs), particularly the Restoration Council of Shan State.

Rakhine and Southern Chin States

In early September, SAC township-level General Administration Department (GAD) officers requested, via SAC-appointed village administrators, that IDPs displaced by armed conflict return home before the end of October. Local media reported on 1 October that the SAC was pressuring IDPs in Kyauktaw and Paletwa townships — who had been displaced by armed violence between the Myanmar military and the AA since 2018 — to return to their places of origin, and had threatened to cut off food supplies or demolish temporary shelters if they did not.[4]

Meanwhile, the SAC has continued its coercive attempts to close the Kyauk Ta Lone camp in Kyaukpyu Township, Rakhine State, which hosts Rohingya and Kaman Muslims who have endured long-term internment in the camp since their displacement in 2012. SAC authorities are close to finalising construction on the chosen relocation site, despite communities’ opposition to the plan. Meanwhile, in August, IDPs in Sittwe Township told this analytical unit of rumours that the SAC were planning to close their camps,[5] illustrating the degree of community concern about this process among other interned Rohingya and Kaman Muslims in central Rakhine State.[6] However two relevant United Nations (UN) officials who spoke to this analytical unit said they had not heard of any iminent SAC plans to close or reclassify camps in Sittwe Township.[7]

Northern Shan State

At the beginning of October, this analytical unit learned from a local NGO that the GAD had reportedly told IDPs in Namtu and Kutkai Townships that their camps would be closed, and that IDPs must either return to areas of origin or move in with relatives elsewhere.[8] Media also reported that, in addition to these two camps, others in Namkham, Manton, and Lashio Townships were also scheduled for closure.[9] However, according to Shwepheemyay News and sources who spoke with this analytical unit, the SAC did not issue any instructions to close or relocate IDP camps in Kutkai Township, which hosts around 4,600 IDPs across 13 sites.[10] In Namtu Township, residents of three camps — known locally as the Kachin Baptist Convention (KBC), Kyu Saw, and Lisu camps — were apparently told that their camps would be closed by the end of October, and they should prepare for departure by 15 October. Around 500 people from 114 households currently live across these three camps.

Southern Shan State

On 10 September, a member of a Southern Shan State IDP committee was reported to have said that the SAC had ordered IDPs living in displacement sites in Southern Shan State to return to their places of origin by the end of October.[11] According to the same report, most IDPs in Southern Shan State are from Pekon and Demoso townships, as well as the Moe Bye village tract. Demoso Township is in Karenni State; Pekon Township and the Moe Bye village tract lie on the border between Karenni and Shan States and are disputed by the two. Many settled in PinLaung and HsiHseng Townships, areas under Pa-O National Organisation (PNO) control.[12]

Background

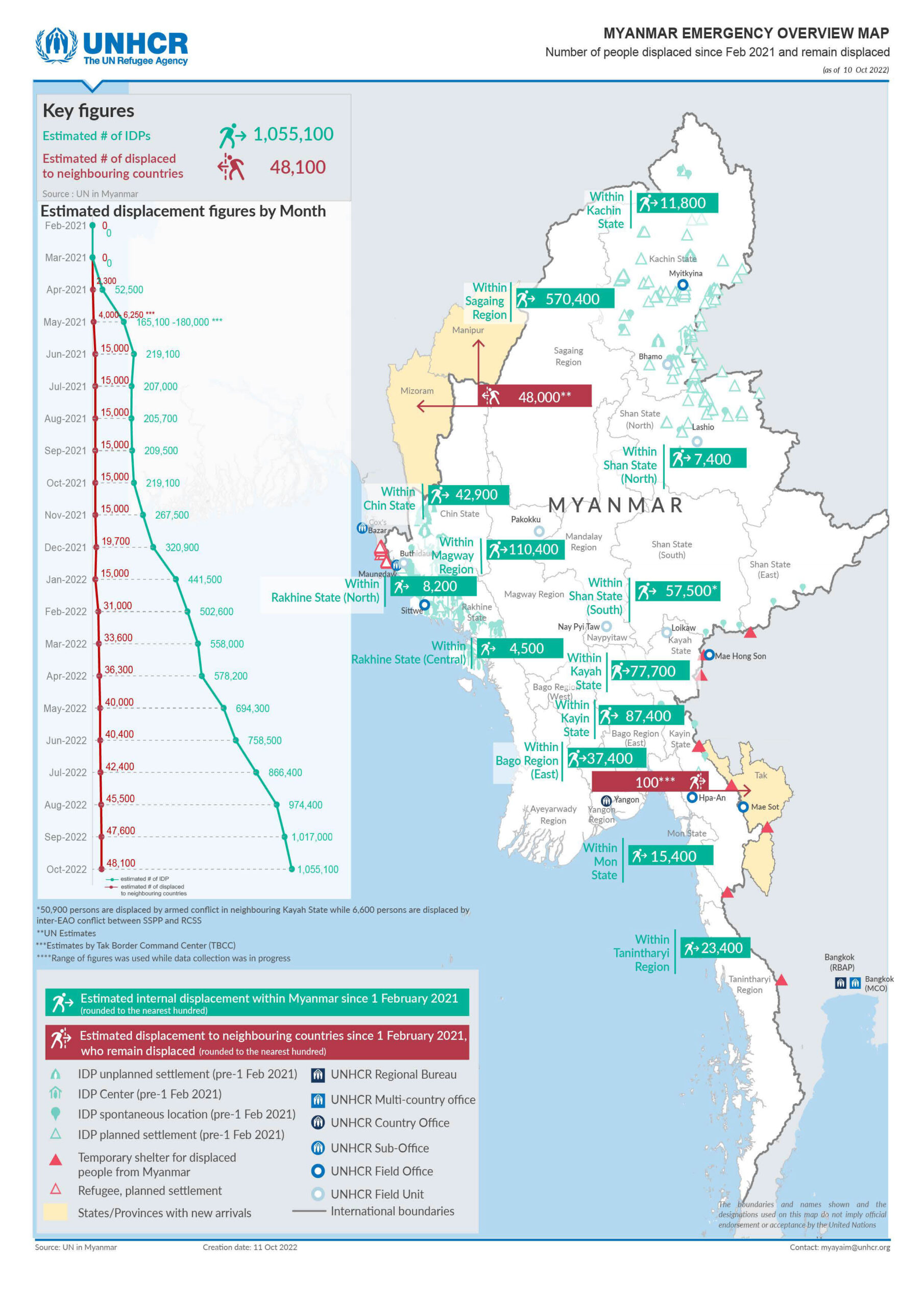

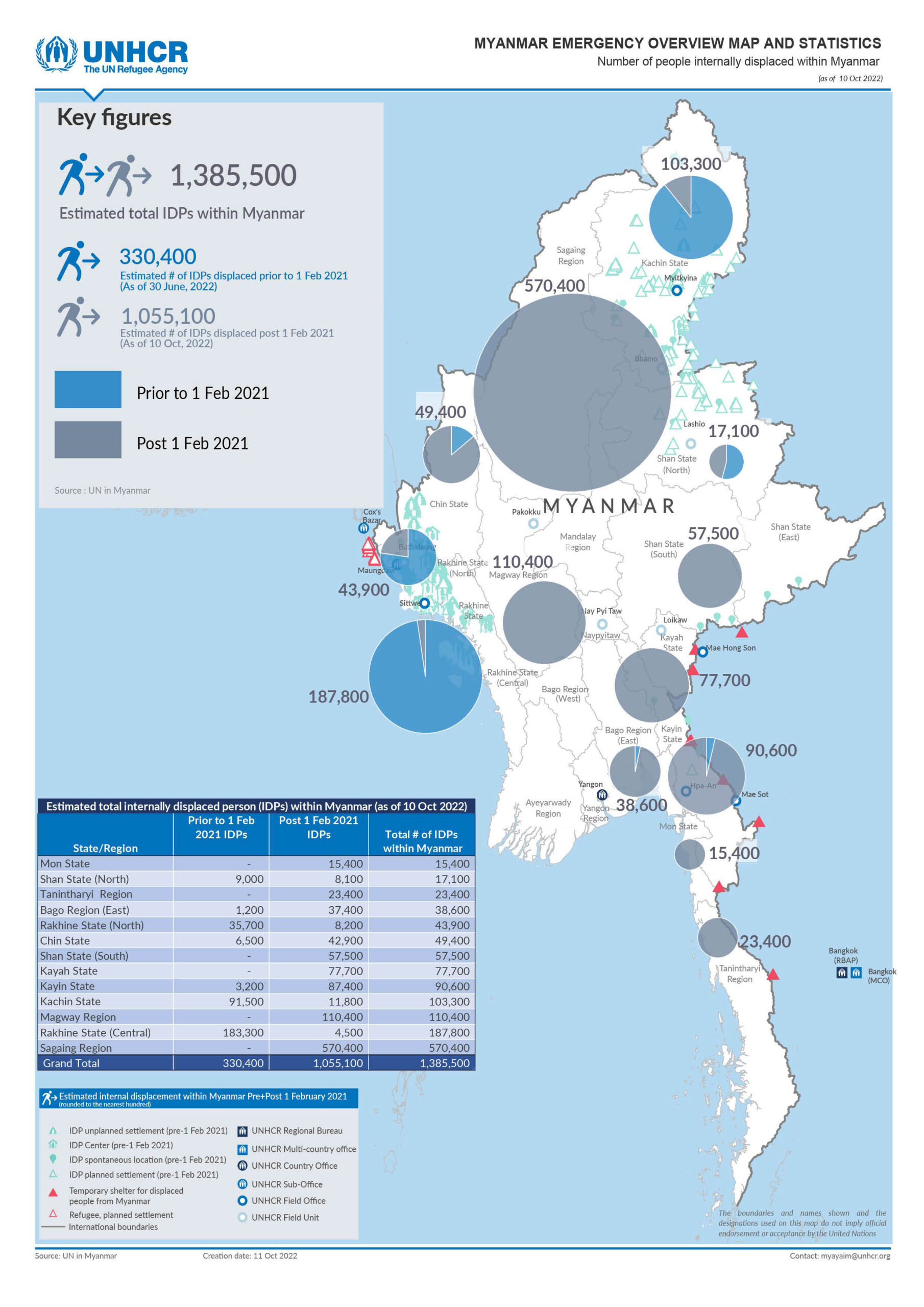

While some IDPs in Myanmar have been displaced over previous decades by historic conflicts, others have been displaced by post-coup escalations. Displacement across the country has risen from an estimated 330,400 people pre-coup to 1,385,500 people by 10 October 2022.[13] Historically, in the Myanmar response, the international community has typically promoted the closure of displacement camps and the return of IDPs to their places of origin as a positive step. The SAC may even see its current efforts to close camps as a way to demonstrate its legitimacy — or at least its willingness to cooperate with the international community’s norms — even while disregarding international standards for safe returns.

Camp closures have been a long-standing issue for the international response over the last decade. In 2019, the elected National League for Democracy (NLD) government finalised its National Strategy on Resettlement of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) and Closure of IDP Camps, after announcing four pilot camp closures.[14] The SAC has continued the process of closing camps and continues to cite the National Strategy as the framework for this initiative, despite the continued violation of clauses related to consultation, humanitarian access, and protection for vulnerable groups.

Some IDPs have returned to their homes since the coup, despite current insecurity. In Kachin State, on 25 May 2022, around 100 households returned to their homes in Thapadaung and Hokap villages, Myitkyina Township, after spending over 10 years in Jang Mai Kawng IDP camp. They had fled their villages in 2011, due to armed conflict between the Kachin Independence Army and the Myanmar military.[15] At the time of their return, the returnees reported to this analytical unit that they saw no signs that the situation would improve in their camps and would therefore prefer to return to their areas of origin;[16] security concerns would be significant in either their location, but support available to those in camps has been declining since the coup. Additionally, in March 2022, some IDPs returned to their villages in rural Ann Township, Rakhine State, from camps in the Ann urban area, after two to four years of displacement caused by armed violence between the AA and SAC.[17] The returnees reportedly received 500,000 Myanmar Kyat per household from the Rakhine SAC.

The SAC camp closure orders reported in September affect IDPs both displaced by recent fighting and by previous conflicts and crises. In Namtu Township, Northern Shan State, most of the IDPs that would be affected by the camp closures were displaced by armed violence in 2016. Conversely, nearly all of the displaced in Southern Shan State have fled post-coup armed violence; most are from outside the state, particularly from across the southern border. By June 2021, intense armed violence in Karenni State had driven a substantial number of IDPs into Southern Shan State.[18] According to UNHCR, as of 10 October 2022, at least 50,900 of the estimated 57,500 displaced people in Southern Shan State come from Karenni State.[19] Even the best available numbers for the area are unlikely to capture the full scope of the displacement crisis; reports to this analytical unit suggest that any IDPs who could do so moved directly into relatives’ homes, while others with the financial means rented private houses upon arrival.[20] Armed violence between the SAC and various resistance groups in Karenni State has remained intense; recently, serious fighting in Moe Bye Township in the first week of September displaced even more people, highlighting the impracticality of the SAC order for others to return home.[22]

It should be noted that while contexts across Myanmar vary widely — as do the challenges facing IDPs — the term ‘camp closure’ has a particularly distinct connotation in Rakhine State. Several of the camps housing Rohingya and Kaman people in central Rakhine State were officially closed by civilian administrations prior to the 2021 coup, but this process is better understood as a reclassification. While other displaced persons in Rakhine State and elsewhere in Myanmar are (generally) permitted to travel, interned Rohingya and Kaman Muslims face draconian restrictions on movement, livelihoods, and access to health and education. Closed camps became villages, and communities saw no improvement in access to basic rights, services, or livelihoods.

Since violence and displacement in 2012, authorities have interned some 100,000 Rohingya and Kaman people in camps in Sittwe Township and 40,000 more in other camps in central Rakhine State.[23] The SAC has continued to push forward camp closures, particularly in Kyauk Ta Lone camp, in Rakhine State’s Kyaukpyu Township. Residents are strongly opposed to the flood-prone relocation site selected by authorities, which is situated between two military battalions. Despite the elected authorities’ commitments under the National Strategy on Resettlement of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) and Closure of IDP Camps, there was no meaningful consultation with communities.

Forecast

At present, it is unclear whether the camp closure orders issued in September across three states are isolated events, or if they are part of a wider — even nationwide — push to close IDP camps. While no national policy has been announced by the SAC, it is striking to see camp closure orders issued across a diverse set of locations at roughly the same time. Essentially: it is still unclear if these camp closures are part of a wider process, or are the result of several localised developments that are coincidentally taking place simultaneously. Several community sources in Northern Shan State who spoke to this analytical unit have said they believe that a secret order had been handed down from the SAC, via the GAD, to close every IDP camp across the country.[25] This rumour is entirely unconfirmed; moreover, several people close to IDP camps in Kachin State told this analytical unit that none of these camps had received similar orders to close.[26]

According to UNHCR, there are currently over one million displaced people in Myanmar; although most of the displaced are in impromptu displacement sites rather than formalised IDP camps, many people are in formal camps and have been for years.[27] Should the SAC attempt to push camp closures on a countrywide scale in the coming months, humanitarian needs could escalate rapidly. For most IDPs, the concerns that triggered their displacement are unlikely to have been resolved — especially since the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2021 coup have resulted in deteriorating conditions across the country, causing additional displacement. Now, more than ever, many IDPs are concerned about explosive ordinance contamination and troop presence near their areas of origin; of particular concern is the presence of SAC forces. As a result, displaced communities forced to leave their camps are more likely to move further afield — to new formal or informal displacement locations — than to return to areas of origin. In many areas, intense armed violence is centred on roads and key routes, and relies heavily on mines and other explosive devices, increasing the risk associated with any movement. The potential closure of camps also would place intense pressure on host communities. No communities in Myanmar have escaped the impact of escalating conflict and crises; resiliency is on the decline amid growing security concerns, deteriorating economic conditions, and looming food shortages.

That said, while at least some of the camp closures that have been ordered are likely to move ahead, there are real questions surrounding the capacity of the SAC to actually implement a forcible camp closure process on the ground. While some IDPs in the camps in question are preparing to relocate, others do not appear to be doing so, indicating that they intend to stay in the camps, regardless of imminent closures.

IDPs in Namtu Township told this analytical unit that they submitted a request to the GAD to remain in their camps until the end of the academic year — around February 2023. They have not received any response as yet, so they are preparing to move ahead with their own resettlement.[28] IDPs in the KBC camp have purchased plots of land around Namtu Town, near neither their current location nor areas of origin, which they are clearing and preparing for construction. They have requested support for construction materials from international agencies, but have not received any responses. In the meantime, they are deconstructing structures at their current location to repurpose the materials for new shelters; however, much of this material is in poor condition. Some households from the Kyu Saw camp, the residents of which are mostly Shan, have started to move to the homes of relatives. Lisu camp residents are also preparing to build houses on new plots of land.

Returns would be particularly difficult for IDPs in Southern Shan State, many of whom are effectively unable to return to their areas of origin in Karenni State due to the extreme levels of ongoing armed violence there. Some may refuse to relocate, risking harassment by SAC or aligned/proxy forces. According to one source who spoke to this analytical unit about the situation facing IDPs in Southern Shan State, the SAC-aligned Pa’o National Organisation (PNO) had arrested two youths from displacement camps in the last month.[29] If IDPs living in camps choose to remain beyond the October deadline (the exact date of which has not yet been stipulated), there is reason to believe the PNO might increase pressure on these IDPs. The most likely scenario is that many of these people will face additional displacement, this time even further afield, possibly into Eastern or Northern Shan State — although camp closures in Northern Shan State may leave limited options there.

It is not yet clear where IDPs facing potential camp closures in Rakhine State’s Kyauktaw Township and southern Chin State’s Paletwa Township would relocate, if anywhere. Ongoing armed violence between the AA and SAC in both townships and surrounding areas means many civilians, including IDPs, are reluctant to travel at all, given the ongoing presence of armed actors and risks of landmines and other explosive ordnance. Rural areas, where IDPs originate from, are especially affected by these dynamics. Harsh restrictions on movement, trade and humanitarian access will also make any return process exceedingly difficult for many. In the absence of safe conditions to return to rural places of origin, many may attempt to remain in camps closer to hubs of community support and what limited livelihood options may remain.

Any attempts to close camps hosting people displaced by armed conflict in Rakhine State and southern Chin State could also fuel the renewed armed violence between the AA and SAC. With the ULA/AA having expanded its own governance structures over recent years, including in displacement sites, it is likely to push back against SAC attempts to assert coercive administrative control over displacement sites and IDPs. Due to this competition, efforts to close camps will most likely result in the increasing politicisation of the camps, with IDPs caught in the middle as competing armed actors to administer them. The SAC has dramatically scaled up its arrests of civilians on charges of associating with the ULA/AA in recent months, and protection risks for IDPs, to include but not limited to arrest, may increase as a result of new administrative competition in camps. This in turn will likely contribute towards ongoing armed conflict dynamics.

For Rohingya and Kaman people interned in camps in central Rakhine State, camp closures would likely continue along established lines in that context, following the precedents they have set in Kyauk Ta Lone, with the ‘reclassification’ of camps into permanent settlements and little attempts by authorities to address long-standing issues regarding freedom of movement or access to basic services. This move toward permanent settlements suggests residents will continue to face long-term internment.

Response Implications

Thus far, it appears that the SAC has not provided any plans or support for communities living in camps that have been instructed to close. IDPs across Myanmar, whether displaced by recent or previous armed violence, face a range of challenges — particularly the difficulty in accessing basic commodities and services amid increasing restrictions and economic deterioration. These challenges could be compounded by the pressure to return to their areas of origin or be displaced again, as return brings with it additional risks associated with growing armed violence, explosive contamination, and the ongoing presence of SAC or other armed actors near areas of origin.

In the case of communities ordered to leave their displacement sites, humanitarian needs are poised to rise dramatically for both the displaced and host communities. Any movement will be difficult and dangerous due to explosive contamination, especially in areas like Karenni State and parts of Southern Shan State. IDPs in Rakhine State have also expressed concerns to this analytical unit over explosive contamination and the lack of access to livelihoods in their places of origin.[30] With the rate at which these closures are moving forward, a rapid response is required. Although this is increasingly challenging given the constricting access across Myanmar, local responders who are already supporting displaced communities will likely be able to keep doing so for as long as their budgets allow and local markets continue to function. However, this too could be threatened by deteriorating security conditions, and some CSOs have ceased operations or shifted to low or zero visibility modalities.

Even as the communities affected by camp closure orders need urgent support, response actors must also consider the possibility that these closure instructions could expand to include other/all displacement sites in Myanmar. Challenges and needs vary widely among different communities and contexts. Communities affected by conflict and crises are currently struggling with the collapsing economy, food and commodity shortages, and armed violence. In this context, the possibility of wide-scale camp closures is particularly concerning, as IDPs tend to have fewer coping mechanisms and are disproportionately vulnerable to heightened insecurity.

Moreover, the IDP status of some camp residents may intersect with other aspects of identity that raise their vulnerability. In Southern Shan State, many of the displaced reportedly consider seeking refuge in monasteries, churches, or IDP camps to be a measure of last resort, due to concerns about weather, lack of available food and support, risk of exposure to COVID-19 and other illnesses, the crowded nature of displacement sites, and harassment by armed groups. As a result, the people who find themselves in IDP camps are likely to be among the most vulnerable — those with no other options available to them. Sources have told this analytical unit that some camp populations primarily comprise women, children, and elderly people, as most men appear to either have joined armed resistance groups or gone into hiding for fear of arrest on suspicion of supporting such groups.[31]

Key Recommendations

- Continued reference to the 2019 National Strategy should be abandoned. For years, much of the international aid community has identified durable solutions as being a key issue in the Myanmar response, and the National Strategy emerged in that context. While the National Strategy never met international standards, even the clauses related to consultations were never meaningfully implemented by the NLD government. Moreover, the SAC is not a legitimate successor to that government, and continued reference to the National Strategy affords an undue veneer of legitimacy to the SAC’s camp closure efforts, which do not even meet the minimum provisions in the National Strategy.

- Recognize that durable solutions, as a concept and a programming stream, requires serious revision and redesign in the Myanmar response. Myanmar in 2022 is a very different context from Myanmar in 2019, when the National Strategy was originally written. Myanmar 2022 is currently witnessing one of the largest — and growing — displacement crises in the world, with large parts of the country now witnessing active armed violence. True durable solutions are flatly not possible in this context at this time. Focus should instead be placed on the preservation of human life and the provision of needed assistance until durable solutions are even conceivable — a process which may take years. Based on this approach, agencies should prioritise lifesaving programming, whether or not spontaneous or forced returns take place fully in line with durable solutions principles.

- Continue to advocate for unrestricted access to communities affected by conflict and crises, including both IDPs displaced by previous conflict and those recently displaced. Although the ongoing narrowing of access is unlikely to reverse course, maintaining pressure on key stakeholders will signal that the international community continues to prioritise the people of Myanmar. This advocacy should not only be directed at the SAC; it should also be directed at other armed actors that control key access routes. Additionally, discussions around access should also consider advocacy which targets elements of the international aid response and donor community, especially those which have continued to focus heavily on rigid direct aid modalities at the expense of more flexible remote programming through local organisations.

- Release emergency funding to respond quickly to urgent needs as they arise across Myanmar in the wake of potential camp closures. In some cases, there is likely little time for lengthy implementation-strategy planning, funding applications, or complex multi sectoral needs assessments. Agencies should assess the communities they are best placed to support should closures go ahead, develop rapid mitigation strategies to offset the risks posed by sudden closures, and begin to prepare responses as quickly as possible.

- Work with local responders to access displaced communities in urgent need of support. Local support mechanisms such as parahita groups and small CSO structures are already in place in many displaced communities, but they — like those throughout all of Myanmar — have come under immense pressure since the coup. These local responders can be the cornerstone of cross border or remote programming modalities, so long as informal money transfer systems can be used and local markets remain functional.

- Support refouled communities in community displacement planning, explosive ordnance risk education (EORE), and emergency first aid training before relocations commence. Future displacement after return is in some cases quite likely, and landmines are a critical issue in nearly every unsafe return. While recognizing that all of the returns that take place as a part of the ongoing camp closure efforts are not safe, secure, or dignified, local and international responders should act quickly to develop plans to support IDPs’ relocation — ideally, within the coming weeks — to help make this process as safe and dignified as possible given the situation.

- Pre-position aid in new displacement sites or within potential host communities. Naturally, such pre-positioning would need to be conducted in the absence of a comprehensive needs assessment; however, it is safe to say that most IDP communities will be in need of support. Because planned relocation sites and host communities lack the resources to meet these needs, and tight restrictions on the transport of food and medicine will make it difficult to deliver needed assistance in a timely manner, pre-positioning is an urgent priority.

[1] Interview on file.

[2] Interview on file.

[3] Interview on file.

[4] During the intense fighting, the military council pressured IDPs from Rakhine and Paletwa to return home, Development Media Group, Facebook post, 1 October 2022: https://www.facebook.com/dmgnewsagency/posts/pfbid0fDE63Zx67EzPVGoooftV6SEi3CW1LWLSSKAQqnH6KmpES9amuPv6sKXjPCANyGxFl; The military council threatened to stop all support if IDPs don’t return home, Western News, Facebook post, 3 October 2022: https://www.facebook.com/watch/?ref=saved&v=480995160417462.

[5] Interview on file.

[6] Interview on file.

[7] Confidential notes on file.

[8] Interview on file.

[9] The Military Council has ordered the closure of the military evacuation camps in North Shan State by the end of October, Shwe Phee Myay News Agency, Facebook post, 19 September 2022: https://www.facebook.com/shwepheemyaynews/posts/pfbid0xGnRRXe6JDUZdXuMFrwWSPR1mzb8Ermia6QcuiKzzCCTMCAXybncArX4qe9LP1Uql?__cft__[0]=AZVlA1_3PR8q04NEl9rtev6Q6bTBYYt5n_f6fq2YPj5F5sP7d3URGRt3YQp0XemClzZ9HGQ3JHia2sDcEjzQfA7-jrYAGi_TDr3MZlN3ZB4tPOftvXN9BfqqpJqOWDCqn8s&__tn__=%2CO%2CP-R.

[10] Although the military council did not order the closure of the 13 military evacuation camps in Kuk Khaing, the aid was banned and restricted, Shwe Phee Myay News Agency, Facebook post, 28 September 2022: https://www.facebook.com/shwepheemyaynews/posts/pfbid0nNzdbwuJV5JSmWr8zH1umbE5hAdZ1smC34bK7aBUwCuFBpzVKQ4cayuAVDHSr9Y4l?__cft__[0]=AZWWib0G6nHoHtrcNipmlBbucbrha7SNNb0my_4Cn4oX3eJusm2WFu3vA62a2diQ5yJgz5jaFjZ3wjnei96KZVSDYe9ErIwWb7GRB1axkurizYFtIkzDCt4FMLZm24wY_06Zplcz3AKtmig99WDMq1Gb&__tn__=%2CO%2CP-R; interview on file.

[11] Military council instructs Shantaung deserters to return home, Shan News, 10 September 2022: https://burmese.shannews.org/archives/30232?fbclid=IwAR3liqS_nMPNJIX3KM4xVHIfW1zDCb4zwNCh2_dZ2SG9eL68VZlCdooDqXQ.

[12] Difficulty in getting food and medicines, Shan News, 22 July 2022: https://burmese.shannews.org/archives/29377.

[13] See the Myanmar UNHCR displacement overview, 10 October 2022: https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/96126.

[14] Ministry Announces Plans to Close IDP Camps in 4 States, The Irrawaddy, 5 June 2018: https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/ministry-announces-plan-close-idp-camps-4-states.html.

[15] Nearly 100 families from Jan Maigaon military displacement camp will return home, Myitkyina News Journal, 22 May 2022: https://www.myitkyinanewsjournal.com/%E1%80%99%E1%80%BC%E1%80%85%E1%80%BA%E1%80%80%E1%80%BC%E1%80%AE%E1%80%B8%E1%80%94%E1%80%AC%E1%80%B8%E1%80%99%E1%80%BC%E1%80%AD%E1%80%AF%E1%80%B7%E1%81%8A-%E1%80%82%E1%80%BB%E1%80%94%E1%80%BA%E1%80%99/?fbclid=IwAR2NhR3OcIKgznIqP6Z7SXZc9oSMrBaaQFlCOi8-RMHLWsISWsVnZS14WN0.

[16] Interview on file.

[17] More than 1,300 displaced people in Ann Twsp return home, Narinjara, 2 October 2022: https://www.dmediag.com/news/4232-1-3k-dspl; IDPs who have returned to Dar Let Village Tract, Ann Township, are facing difficulties due to a prohibition on carrying rice and a food shortage, Narinjara, 2 October 2022: https://www.facebook.com/narinjara.info/posts/pfbid03766kTcNdFyDqjeaw94mYZvbRf36AKr5c4LeHd5FwXMQFhKtTU18zHbWnV616Qm9Rl.

[18] It is difficult to support the Karenni fleeing the war, Shan News, 1 June 2021: https://burmese.shannews.org/archives/22324.

[19] See the Myanmar UNHCR displacement overview, 10 October 2022: https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/96126.

[20] Interview on file.

[21] Interview on file.

[22] In the battle of Moebye, the battle with the military council continued fiercely, Mara Star Chanel, Facebook post, 9 September 2022: https://www.facebook.com/marastarchnnel/posts/pfbid0vW11ft8LoSmViyMjzxd6XiTKRRT56sWdEeUuRyhhgLVwPkV6M7C8foT7Q982s3Lml?__cft__[0]=AZX8z7hcdr46s_6FvrMCplSkG1SK3IVLLYuhpfsxExc7V9jZ1OjOa5xsdFGlw2eurF1Hq_AV_e-cRyzryveKJjqD0C1lmIEEDdUKD61nf-naJDBaRcXKfCa92vIGkMWf30DWYrOoBWyAAVQTzfJA0cCI&__tn__=%2CO%2CP-R

[23] “‘An Open Prison Without End’: Myanmar’s Mass Detention of Rohingya in Rakhine State,” Human Rights Watch, 8 October 2022: https://www.hrw.org/report/2020/10/08/open-prison-without-end/myanmars-mass-detention-rohingya-rakhine-state.

[24] Myanmar UNHCR displacement overview, 10 October 2022: https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/96126.

[25] Interview on file.

[26] Interview on file.

[27] See the Myanmar UNHCR displacement overview, 10 October 2022: https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/96126.

[28] Interview on file.

[29] Interview on file.

[30] Interview on file.

[31] Interview on file.