Executive Summary

This report summarises the findings of the EU’s civil society consultations in advance of the seventh Brussels Conference on Supporting the future of Syria and the Region, which will be held on 14-15 June 2023. The consultations took two forms: in-country consultations with civil society organisations (CSOs), and an online survey of Syrian individuals and CSO representatives in Syria and the wider region carried out on behalf of the EU by the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR).

In-country consultations with civil society were carried out between March and May 2023 to identify recommendations and key topics for the Brussels VII Conference in Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon. These events, held both in-person and online, gathered representatives from NGOs, civil society, and international stakeholders to foster exchange and explore key topics within the Syria response for the upcoming year.

The survey was open from 19 April to 5 May and collected the opinions of 1467 CSO representatives and 595 individual Syrians across four key topic areas identified by the in-country consultations:

- Civic Space and Political Processes

- Basic Services in Syria

- Early Recovery and Livelihoods

- Displacement and Durable Solutions

Each topic area contained multiple questions to gauge the opinions of Syrian civil society on the effectiveness of the humanitarian response to the crisis in Syria, key challenges faced by civil society organisations, and priorities for the future. The results were analysed by COAR and are presented in this report, with comparisons between respondents based on location and whether they are CSO representatives or individual Syrians included where relevant. While results were also analysed by gender and age, there were no significant differences in responses between the different groups. The key findings for each topic area are summarised below.

1. Civic Space and Political Processes

In this section, CSO representatives and individual Syrians were asked separate questions to ensure that they could answer based on their own experiences. Individual Syrians were asked about their involvement in community decision-making as well as whether their needs are met by the response to the crisis in Syria. While over half of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they are meaningfully involved in community decision-making in their current locations, only around a third agreed or strongly agreed that their needs are met by both civil society’s and the international community’s response to the Syria crisis.

Respondents in Jordan most strongly expressed that the operational environment for civil society in their country of operations was “good” or “very good,” while respondents from Lebanon were the most likely to rate the operational environment as “bad” or “very bad.” Across all countries, CSO respondents pointed to the suspension of support and funding, as well as difficulties in bank transfers, as key challenges faced in the past 12 months. Overall, 40% of CSO respondents said that the operational environment had improved in their country of operations over the past 12 months, citing “better cooperation between civil society organisations” and a “better security environment” as the most important reasons. For the 23% who said that the operational environment had deteriorated, the most cited reasons were “reduced funding,” “economic conditions,” and “decreased international support.” Respondents pointed to increased funding, increased international support, and capacity strengthening as key aspects that are needed to strengthen the role of civil society in the aid response to the crisis in Syria.

CSO respondents were also asked about the impact of the 2023 earthquakes, pointing to “lack of available funding,” “difficulty in accessing funding,” and “limitations of international support for the reconstruction of collapsed infrastructure” as the main challenges affecting civil society following the earthquakes. Later in the survey, almost all CSO respondents highlighted “shelter” as the key sector affected by the earthquake, followed by “livelihoods,” “health,” and “education.”

2. Basic Services in Syria

Respondents selected “education” as the priority area for projects targeting basic services in Syria, followed by “health” and “water, sanitation, and hygiene.” Notably, individual Syrians selected “addressing corruption” to a much greater degree than CSO respondents. Respondents pointed to “lack of funding” and “the absence of a political solution to the conflict” as the key impediments to improving basic services in Syria, again with over half of individual Syrians highlighting “corruption” as a key challenge.

3. Early Recovery and Livelihoods

Almost half of respondents said that access to jobs and livelihoods for Syrians had deteriorated over the past 12 months in the countries where they operate — Jordan was the only country where more than a quarter of respondents said access had improved. Northeast Syria was the only area in which less than half of respondents said access to jobs and livelihoods had deteriorated — although only 18% said that access had improved.

Respondents pointed to “inflation” as the key reason for the decline in access to jobs and livelihoods, and advocated for “specialised education programmes (such as technical or vocational training)” and “small business support/support for entrepreneurs” to help improve access. Here again, individual Syrians pointed to “addressing corruption” to a much greater extent than CSO respondents. On enhancing the effectiveness of recovery efforts, respondents selected “linking humanitarian and development work,” “ensuring the sustainability of the response,” and “accountability and transparency in coordination and aid delivery.” “The absence of a political solution to the conflict,” “lack of funding,” and “corruption” were the three most commonly chosen obstacles to the success of projects seeking to restore services and livelihoods in conflict-affected areas of Syria.

4. Displacement and Durable Solutions

Respondents overwhelmingly noted the “risk of deportation/evacuation” as the main challenge faced by Syrian refugees in host countries, alongside “growing anti-refugee sentiments,” “poor security situation/personal safety issues,” and “lack of legal protections.” “Stronger legal protections and political pressure on host countries to protect refugee rights” was the most selected response to what is needed to support Syrian refugees, followed by “support with jobs and livelihoods/employment opportunities” and “more funding for projects focused on the integration of refugees with host communities.” To facilitate the safe, dignified, and voluntary return of refugees to Syria, a majority of respondents noted the need for “a political solution to the conflict” and “safety and security guarantees.”

Regarding internally displaced Syrians, respondents selected “risk of additional forced displacement,” “lack of employment opportunities,” “lack of funding to address long-term needs,” and “poor security situation/personal safety issues” as the main challenges faced. “Support with jobs and livelihoods/employment opportunities” and “more funding for projects focused on the integration of internally displaced Syrians with host communities” were selected by a majority of respondents as needed to support internally displaced Syrians, while again, “a political solution to the conflict” and “safety and security guarantees” were the most frequently selected answer for what is needed to facilitate their safe, dignified, and voluntary return to their communities of origin.

1. Introduction

This report summarises the findings of the EU’s civil society consultations in advance of the seventh Brussels Conference on “Supporting the Future of Syria and the Region,” which will be held on 14 and 15 June 2023. In-country civil society consultations were carried in Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon to identify key topics of interest for discussion during the “Day of Dialogue” on 14 June, bringing together civil society representatives, key decision-makers from countries neighbouring Syria and donor countries, as well as institutional stakeholders such as the EU and the UN to engage in dialogue on Syria and the region. The EU commissioned an online survey to capture opinions and recommendations from Syrian civil society and individual Syrians, from both inside and outside the country, on the topics and themes of interest generated from the in-country consultations: Civic Space and Political Processes, Basic Services in Syria, Early Recovery and Livelihoods, and Displacement and Durable Solutions. There were a total of 2,062 valid respondents to the survey, defined as having completed the first demographics page.

Following this introduction, the report is divided into two main chapters, which outline the main findings of the in-country consultations and the online survey. The results of the in-country consultations are described country by country, while the results of the online survey are presented across five subsections: an initial demographic overview of respondents, and then a subsection for each theme. The data is visualised using charts and maps, showing top-level data of all respondents or data segmented by demographic or other variables where these recorded a significant difference. Additional context and explanations are provided in-text.

1.1. Methodology

The online consultation was designed by COAR in close collaboration with the EU, based on the priority topics for the Brussels VII Conference identified by the first round of in-country consultations in Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon. The survey was created using SurveyMonkey and made available online between 19 April and 5 May in Arabic, English, and Turkish. Respondents were actively sought through social media channels and direct mailing lists. The survey was open only to respondents aged 18 or over.

The survey was designed to capture the opinions of both CSO representatives and individual Syrians inside Syria as well as in neighbouring countries and within the EU. The initial questions captured demographic information such as age, gender, type of respondent (CSO or individual Syrian), and country-level location. While the survey used “skip logic” to ensure that respondents only answered questions relevant to their experiences, our aim was to ensure that as many substantive questions as possible were answered by all respondents to allow for comparison. Most questions were multiple choice (allowing for the selection of up to three answers), with an option to skip and an option to select “Other” and specify a response in-text. A total of 46 questions across 23 pages were uploaded to SurveyMonkey, although due to the skip logic, most respondents were presented with around 30.

1.2. Limitations

- Data collection began at the end of the month of Ramadan, coinciding with Eid al-Fitr, which limited the number of people willing to complete the survey during this time. Labour Day/International Workers’ Day also fell during the data collection period. To compensate for this, data collection was extended for two additional days to allow as many respondents as possible to participate.

- To ensure that the data collected was as comparable as possible between individual Syrians and CSOs, the same survey was used for all respondents — with some minor changes using skip logic.

- Some of the terminology and phrasing used may not have been understood by respondents who were not familiar with the context of the humanitarian response to the Syria crisis.

- Respondents working for CSOs outside Syria were asked to select all countries of operations. 48 respondents chose more than one, meaning that their answers are counted twice in analysis that looks at countries of operations below.

- Outreach efforts broadly targeted countries in the region; however, time and resource constraints meant that COAR was only able to receive a limited number of responses from Egypt and Iraq (11 and 40 CSO responses and 1 and 4 individual Syrian responses, respectively).

- While efforts were made to ensure the survey was not too onerous to complete, the average amount of time spent was 16 minutes. This led to a significant drop-off rate in responses throughout the survey, particularly for individual Syrian respondents. Nevertheless, due to the structure of the survey, partial data was collected from these respondents and included in the below analysis.

2. In-country Consultations

In-country consultations with civil society were carried out between March and May 2023 to identify recommendations and key topics for the Brussels VII Conference. In Amman, Jordan, the NGO-organised “Hear Our Voice” event took place on 13 and 14 March 2023, gathering representatives from 15 NGO fora and other coordination mechanisms for the Syrian diaspora, as well as organisations working in Syria and neighbouring refugee-hosting countries. In Lebanon, an online survey was conducted by the EU Delegation to identify the themes for consultations, and a two-day “Days of Dialogue” event was held in Beirut on 3 and 4 April 2023, fostering exchange between civil society, the EU, the UN, and the Government of Lebanon on the selected themes. In Syria, the “Syrian Civic Space Initiative”, led by the EU Delegation, carried out three sessions on 8, 9, and 10 May 2023. The below sub-sections outline the key results of the in-country consultations.

2.1. Jordan — Hear Our Voice

The event was organised by a steering committee representing 15 NGO fora and other coordination mechanisms. 95 participants (over half of whom represented locally-led organisations) attended in-person, and 38 attended virtually. Participants emphasised that the Brussels VII Conference agenda should reflect the interconnectedness of topics like early recovery and resilience and internal displacement and refugee return, and recommended and discussed three overarching themes for inclusion: Early Recovery, Resilience, Internal Displacement in Syria; Integration in Refugee-Hosting Countries and Return to Syria; and Localisation.

Participants stressed the need for a common vision in early recovery and resilience programmes. Barriers to coordinated action include conflict, displacement, economic instability, limited funding, and the exclusion of community empowerment activities. To overcome these challenges, participants suggested that stakeholders should focus on improved assessments, sustained funding, capacity strengthening of locally-led organisations, and engagement with de facto and local authorities. Conflict sensitivity was also highlighted as a core need in the analysis of the context in which early recovery and resilience programming takes place, as well as stronger communication between donors, implementing organisations, and policymakers on the limits to early recovery activities.

Participants highlighted that conditions for internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Syria remain unfavourable, particularly in earthquake-affected areas. Investment in self-reliance through income-generating activities, rehabilitated infrastructure such as schools and hospitals, and strengthened capacity for local authorities to deliver basic services was suggested as a means to reduce reliance on camps and facilitate IDP return.

On refugee integration and possible return to Syria, participants emphasised a political solution to the conflict in Syria as a prerequisite to addressing the root causes of the humanitarian crisis. Absent a political solution, participants insisted that repatriation would be impossible, and that integration and resettlement should remain at the top of the aid community’s agenda. Inclusive coordination across the nexus was identified as a pathway to ensuring social cohesion and refugees’ access to services, livelihoods, and education — with a suggestion that refugee-inclusive development projects are pursued to ensure access to formal labour. Participants emphasised the reframing of integration as a protection issue rather than an access to services issue, calling on UNHCR to play a greater role in host countries, particularly in refugee registration. Protection concerns inside Syria were raised as a key issue for displacement-affected communities in particular, with the need for protection monitoring of returnees and a particular focus on housing land and property rights.

Participants discussed partnership, leadership, and funding as the three pillars of localisation, highlighting unbalanced power dynamics in the aid environment and the need for a power shift based on principles of equity. This entails the more meaningful involvement of local and national NGOs in all stages of programming, particularly before and after implementation, and opening space for locally-led organisations to take meaningful leadership roles in coordination bodies. Participants emphasised the need for dedicated funding for advocacy, policy, and coordination positions in locally-led organisations to ensure that such groups have the capacity to meaningfully participate in policy processes, as well as funding for institutional-level support, such as establishing organisational structures, achieving financial sustainability, and access to budget lines for overhead costs, training, and security.

2.2. Lebanon — The Local Voice Dialogue

The initial phase of consultations in Lebanon consisted of an online survey among civil society platforms to identify themes for discussion, which resulted in: access to services for refugees; maintaining comprehensive protection for refugees; durable solutions; localisation and partnerships; and strengthening national capacities for basic services. These themes were discussed in a two-day, in-person event at Beirut Digital District, which included representatives of civil society, the EU, the UN, and the Government of Lebanon.

To address the needs of all vulnerable populations, participants emphasised that donors and the international community should adopt a “Whole of Lebanon approach” in which the needs of all populations are addressed on the basis of vulnerabilities rather than nationality or status. Participants called on donors and the international community to pressure the Government of Lebanon to address hate speech towards refugees as well as humanitarian organisations, with special attention given to women, children, LGBTQIA individuals, older persons, and persons with disabilities. Participants noted that fulfilling commitments requires quality funding for efficient aid delivery and conflict-sensitive approaches to prevent further deterioration of relations between and within communities in Lebanon.

On access to services in Lebanon, participants suggested that donors and operational partners should promote integrated programming that supports productive sectors, such as agriculture, and prioritises micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises, with the Syrian workforce viewed as an economic opportunity rather than a burden. Participants emphasised the need for more funding and resources to non-formal education and making schools safe for all children, as well as improving mental health and substance abuse service provision.

To strengthen national capacities for service delivery, participants highlighted the need to foster partnerships between community-based organisations, local and national NGO networks, INGOs, government, and donors, with support at the municipal level playing a vital role in improving service delivery. Donors and civil society were encouraged to advocate for comprehensive reforms while ensuring government accountability for access to basic rights and services. Participants emphasised that the integration of protection and gender mainstreaming principles is needed, particularly in addressing emerging violations and providing essential services for women and children affected by negative coping mechanisms.

Participants advocated for the meaningful engagement of local and national NGOs in programme design, with international donors and actors engaging them as equals, recognising their expertise and capacity, and adopting targeted capacity-sharing, and with quality funding and support. Participants emphasised the need to support local and national NGO fora and networks to foster dialogue, empower local voices, and strengthen their influencing capacities, with such collaboration reinforcing complementarity and avoiding competition. Participants also noted that localisation is needed to collectively restore the social contract between societies and institutions, through amplifying the voices of affected communities and involving local authorities.

Participants called on the Government of Lebanon to respect the non-refoulement principle and allow UNHCR to resume refugee registration to ensure the protection of the rights of Syrian refugees. They noted the need for international mandated organisations to have access to monitor the situation in Syria and establish when the situation is conducive for returns. Participants called on EU Member States and the international community to uphold responsibility-sharing commitments and maintain or increase resettlement opportunities, and emphasised that complementary pathways, such as community sponsorship and scholarships, should be supported for Syrian refugees in Lebanon.

2.3. Syria — Syrian Civic Space Initiative

The Syrian Civic Space Initiative (SCSI) conducted a consultation session in late March to agree on proposals for topics that the participants would like to discuss in greater detail and which could be reflected in the agenda of the Day of Dialogue. Subsequently, the SCSI held three online sessions focused on basic services and the transition from emergency to sustainable responses, civic participation in the political process, and localisation. 113 participants — from every area inside Syria, as well as neighbouring countries and the wider diaspora — took part.

In the first session on 8 May, focused on “basic services and the transition from emergency to sustainable responses,” participants highlighted the importance of supporting local governance actors to develop tools and structures to better respond to realities on the ground, while empowering local communities and activating private sector responsibility. Participants emphasised the need to build the local capacities of organisations and communities, with more flexible procedures to channel support to entities working in Syria. Programmatically, they called for a particular focus on projects that support and enhance the role of youth and women in economic empowerment and early recovery as well as developing value chains between regions and organisations.

Participants recommended a focus on linking education to the labour market, providing high-quality vocational education, and addressing educational gaps through targeted programmes and practical alternatives that compensate for weak services such as electricity and internet access. They emphasised the importance of digital education and support training for educators as well as developing initiatives to harness the potential of university students to bridge educational gaps for younger age groups. Participants also noted the need to ensure sustainable support for governance in and institutionalisation of the healthcare sector to secure essential services.

Participants recommended adopting a human-rights-based approach and providing basic services to ensure voluntary and safe return for displaced persons, noting that the focus should be on rehabilitating infrastructure, schools, housing, and essential services, with special attention to remote rural schools. Social cohesion was highlighted as a particularly important element of the safe return of IDPs, with programming targeting media noted as a mechanism for bridging social gaps and providing a unifying discourse free from stigmatisation. Participants emphasised that Al-Hol camp requires special programming to secure safe areas in case residents leave.

In the second session on 9 May, focused on “civic participation in the political process,” participants recommended increased communication and dialogue programmes between civil and political actors, alongside programming focused on good governance, constitutional and legislative reforms, and expanding the scope of freedoms and human rights. They called for supporting neutral and objective research institutions to investigate social and political issues, as well as for supporting sustainable and continuous political empowerment programmes and facilitating access to political and international platforms.

Participants stressed the importance of fully implementing UN Security Council Resolution 2254, involving local communities in project planning, and promoting legal accountability, as well as enhancing the role of civil society, empowering women’s political leadership, and safeguarding displaced persons’ and refugees’ rights. Participants called on donors to pressure authorities to allow prison visits and address missing individuals, as well as work on supporting the rule of law, impartial judicial processes, and a Syrian-focused economic recovery to support long-term peacebuilding and community cohesion efforts.

In the third session on 10 May, focused on “localisation,” participants emphasised the importance of adopting a decentralised approach that involves communities in planning and implementation processes to achieve localised development. They recommended supporting joint initiatives between local civil actors, municipalities, trade unions, and technical entities, as well as encouraging the creation of local and national dialogue spaces and participatory rapid research on the state of civil society. Participants noted the need for direct communication between local organisations and donors, enhanced transparency procedures, and an increased role for civil actors in accountability, monitoring, and evaluation.

Participants emphasised the importance of supporting horizontal linkages and networks to unify the civic voice across Syria, as well as of evaluating existing policies to identify gaps, and creating inclusive platforms for coordination and advocacy. Participants recommended assessing community leaders’ capacities and addressing gaps to promote decentralisation during early recovery, emphasising the need for capacity building in practical research, humanities, and social sciences to help improve planning at the community level. Encouraging community participation in decision-making, supporting international collaboration, and fostering local leadership, particularly among women, were also highlighted.

Participants recommended that funding should address local needs and consider security-related challenges, suggesting increasing local organisations’ independence by capitalising on local resources, enhancing access to donors, and reducing the number of intermediaries. Donors were advised to maintain volunteer teams’ flexibility, finance integrated youth programmes, focus on community entrepreneurship, and support local and national networks, while sharing risks with local organisations.

Participants highlighted the need for a supportive legislative environment for civil action, urging pressure on the Government of Syria to cancel security checks and travel bans on civil actors and activists to allow them to participate in conferences and platforms. To enhance the sustainability of local organisations, participants suggested designing projects with partial profitable impact, and linking civil entities with the private sector for investment. Participants recommended strengthening communication channels with beneficiaries, efficient third-party monitoring, and adopting a human rights approach for partner organisations, as well as revitalising the energy and inclusion of the diaspora through targeted programming.

3. Online Civil Society Consultations

3.1. Demographic Information

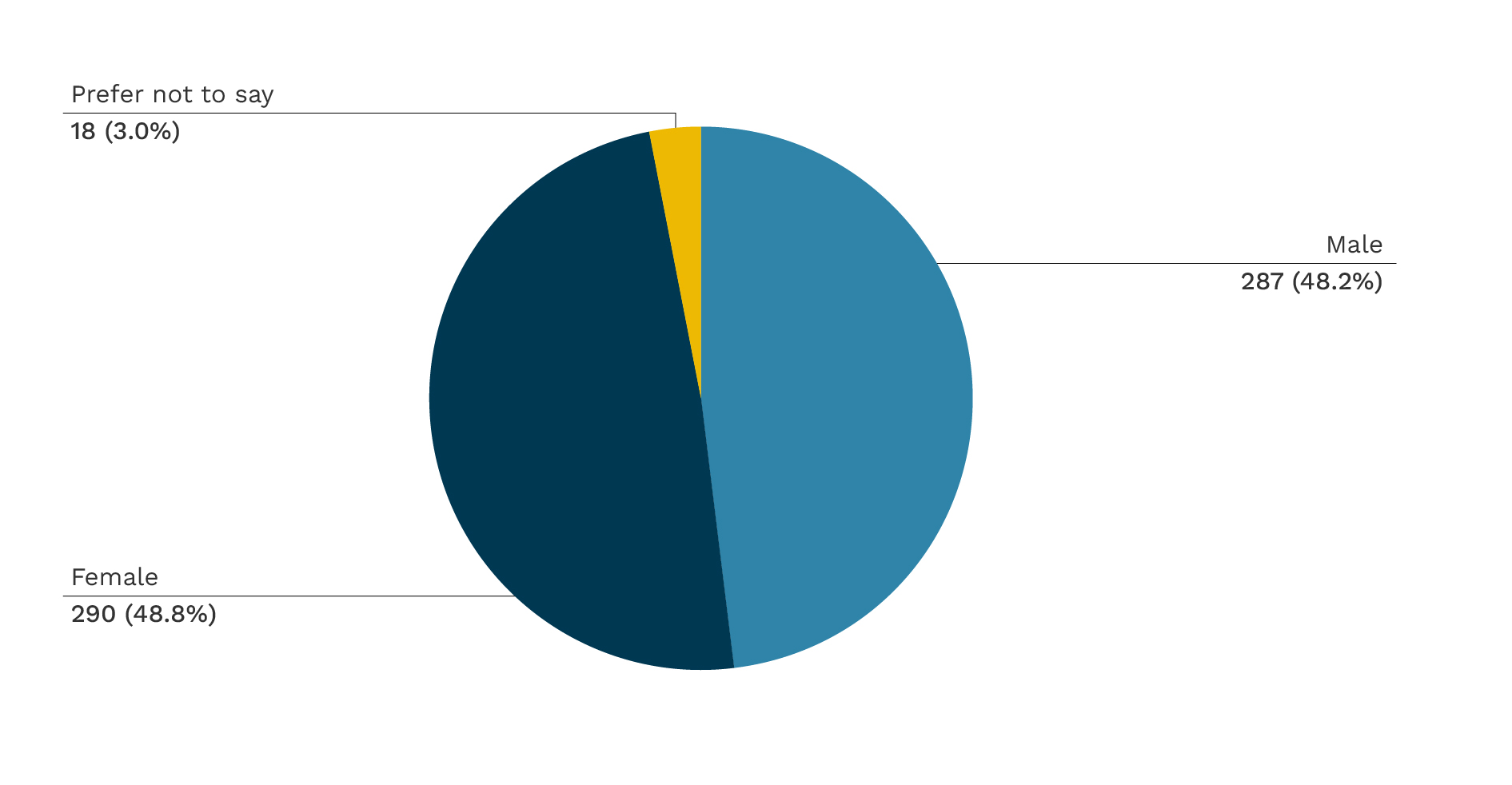

Figure 1: Respondent Category

The survey recorded 2,062 valid responses, defined as having completed the demographics page which asked about gender, age, and type of respondent (CSO representative or individual). Around two-thirds of respondents (1,467) represent CSOs, while the remainder (595) are individual Syrians not affiliated with CSOs. CSO respondents were further subdivided into CSOs based inside Syria, CSOs based outside Syria but working inside Syria (cross-border CSOs), and CSOs working with Syrians in other countries (CSOs outside Syria). A clear majority of CSO respondents have some form of operations inside Syria.

Figure 2: What type of organisation do you work for?

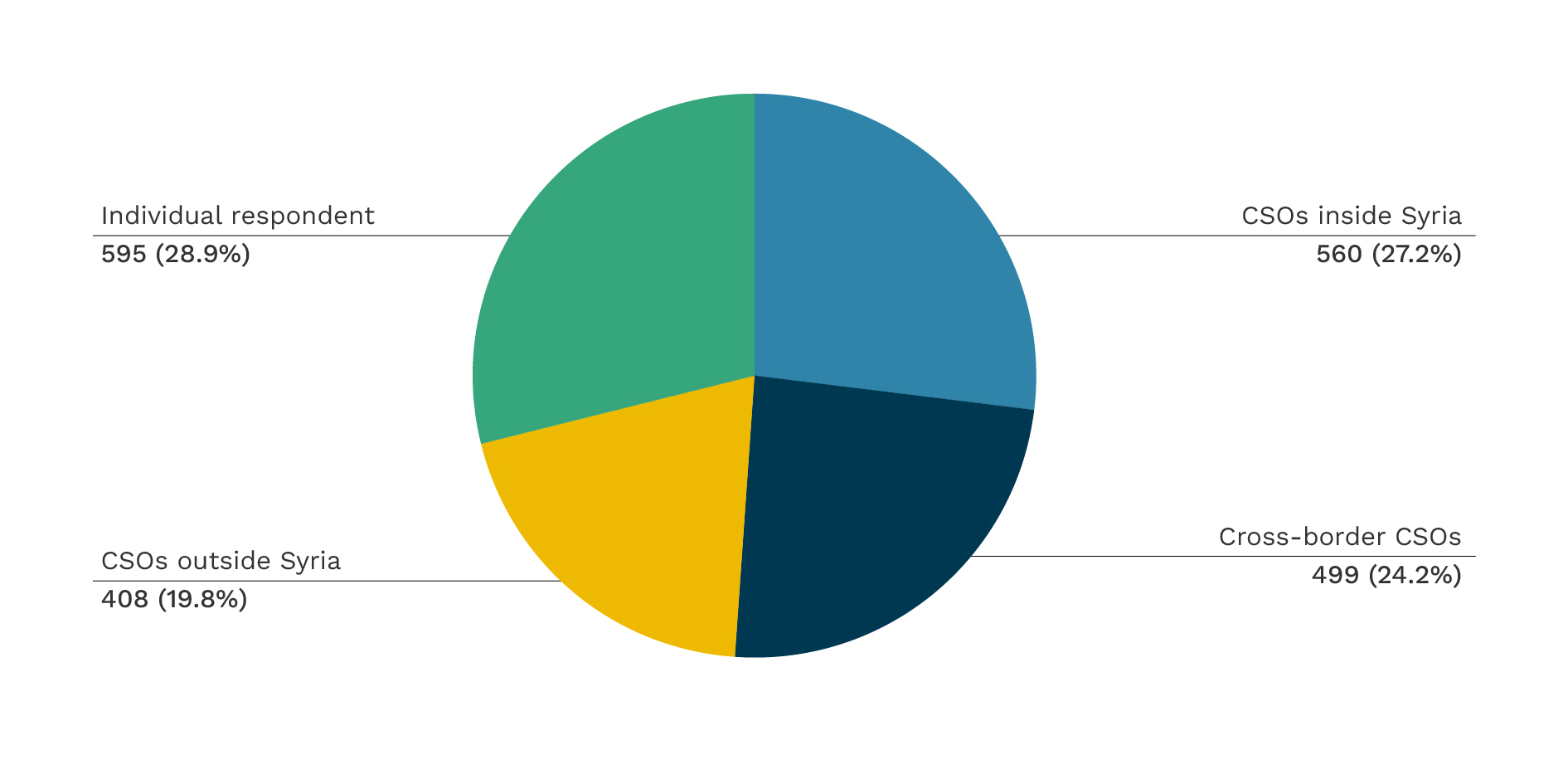

Of the 1363 respondents who specified the type of organisation they worked for, a clear majority chose either national non-governmental organisation (404) or international non-governmental organisation (474).

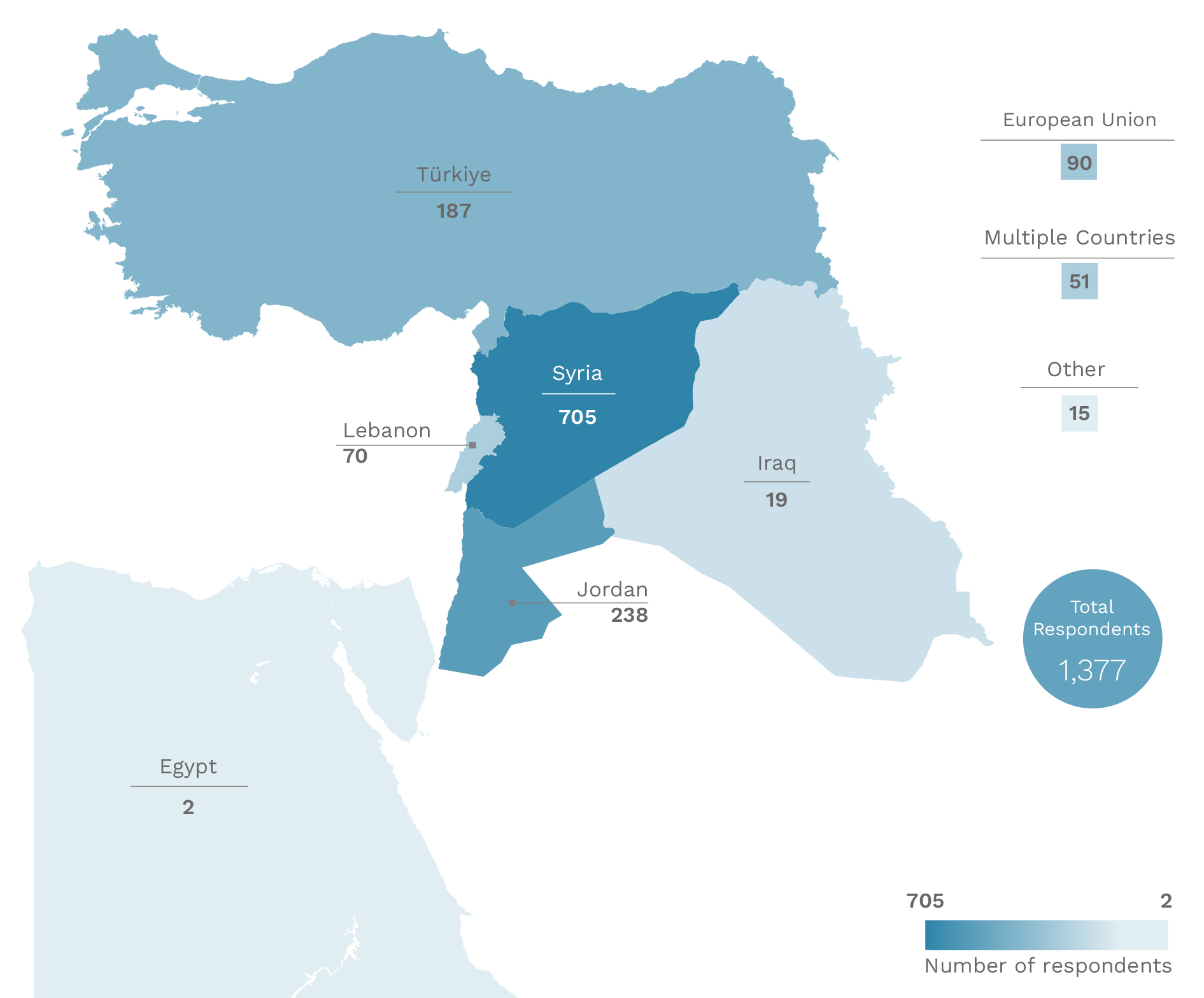

Figure 3: Country locations of CSO Respondents

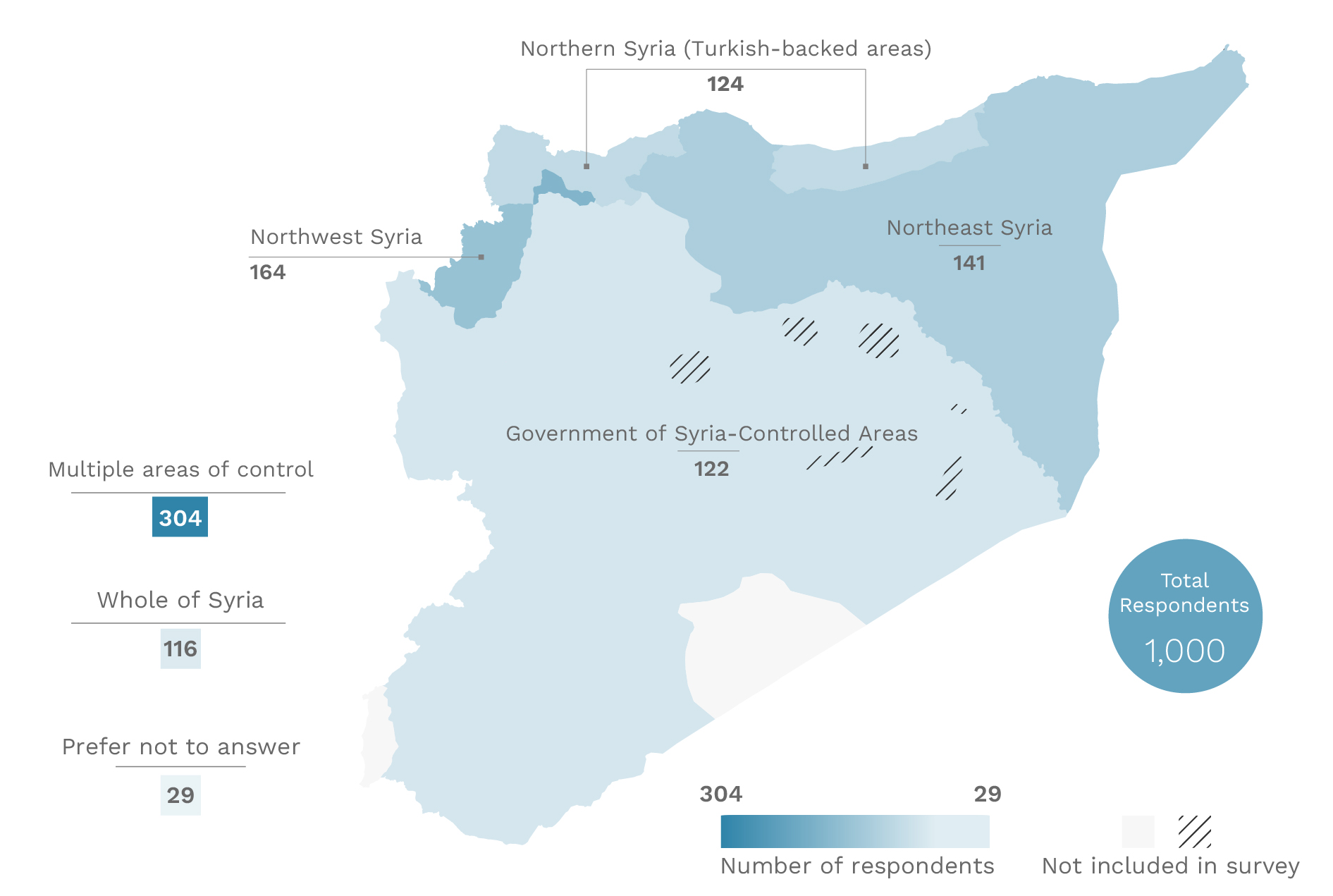

Of the CSO respondents who specified a country of work, over half were based in Syria, followed by 17% in Jordan and 14% in Türkiye. CSO respondents operating in Syria were asked to specify the areas in which they work. For conflict-sensitivity purposes, the locations were specified at the governorate level (and sub-governorate level for areas of shared control), and aggregated. 55% of respondents selected areas in only one zone of control, while 30% of respondents selected locations across more than one zone of control. 12% of respondents indicated that they work across the whole of Syria.

Figure 4: In which areas of Syria does your organisation operate?

3.1.1. Individual Syrians

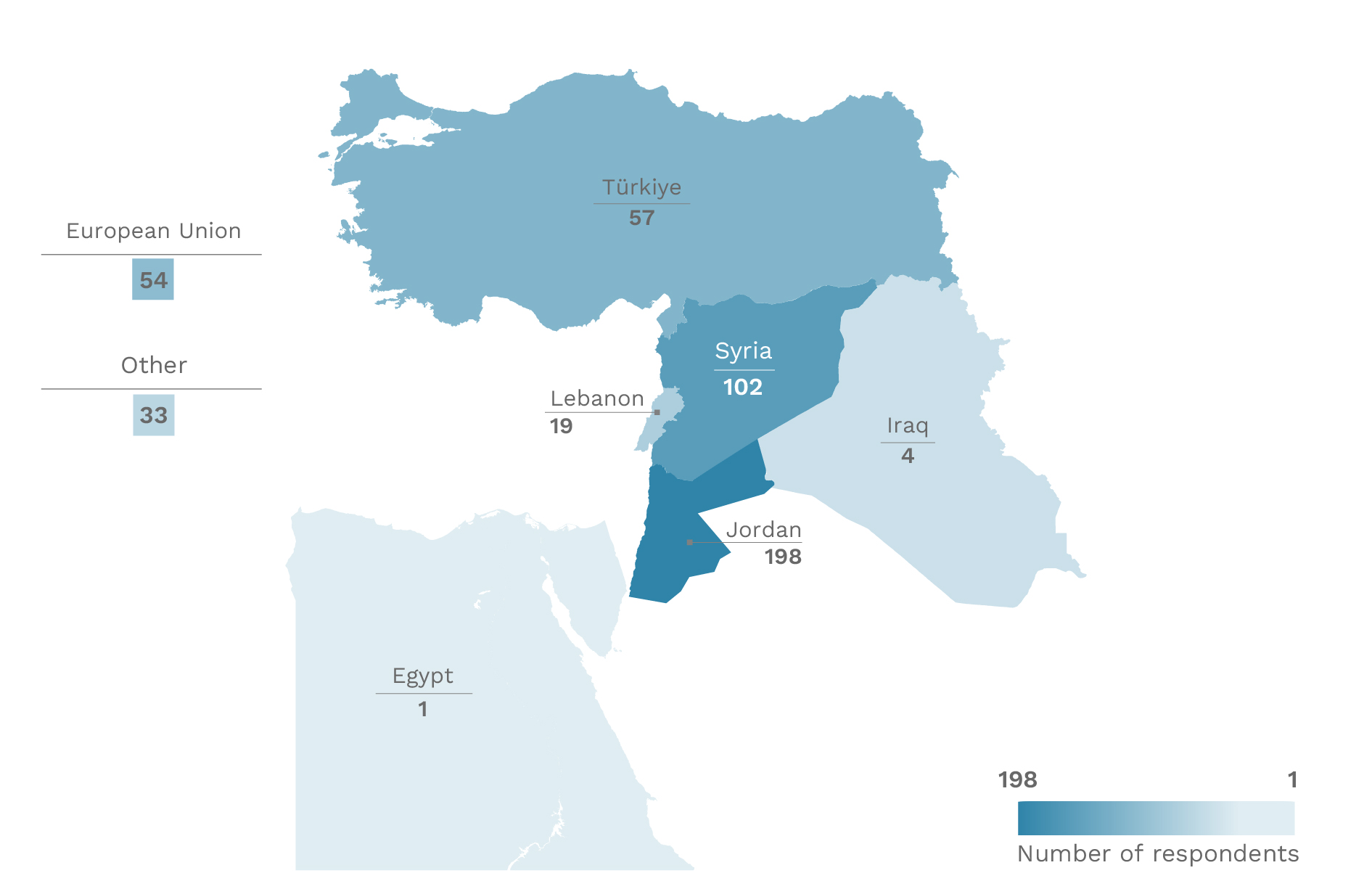

Figure 5: Where do you currently live?

Of the individual Syrians who specified their location, 198 reside in Jordan, 102 in Syria, 57 in Türkiye, and 54 inside the European Union. The respondents that selected “other” included some in Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries, as well as the United Kingdom, the United States, and North Africa.

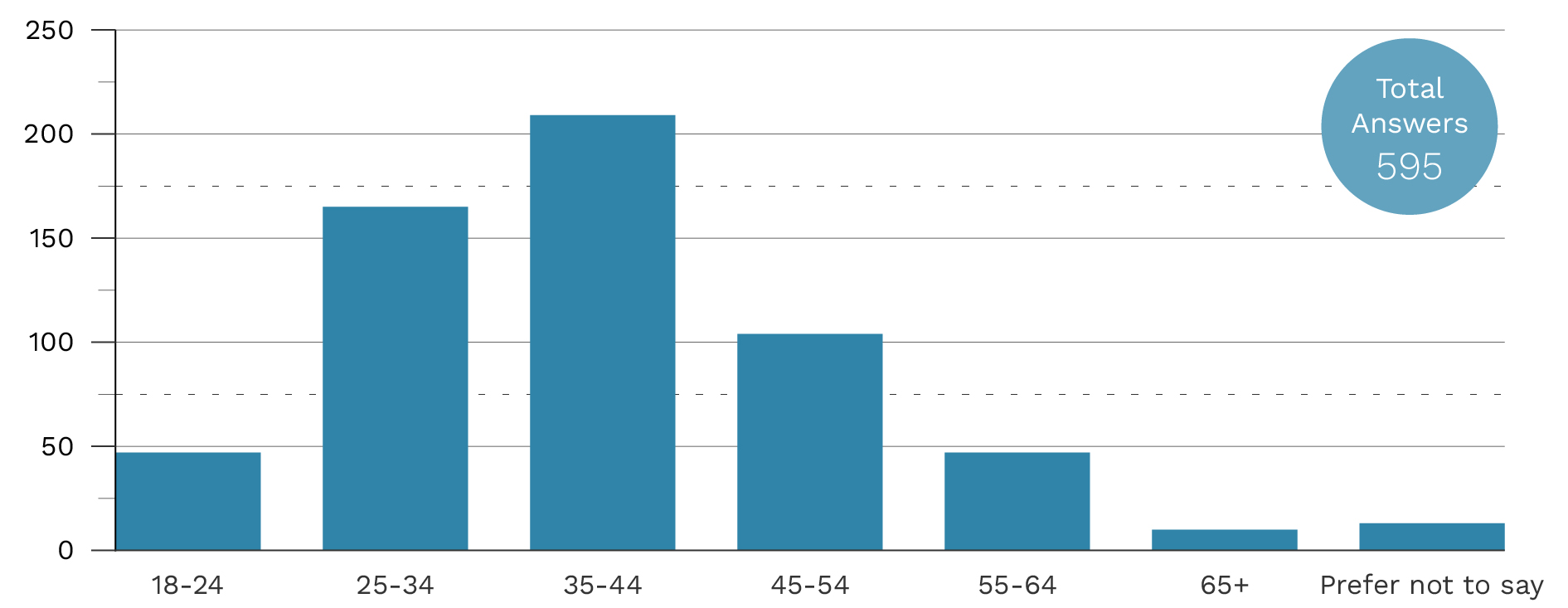

Figure 6: What is your age?

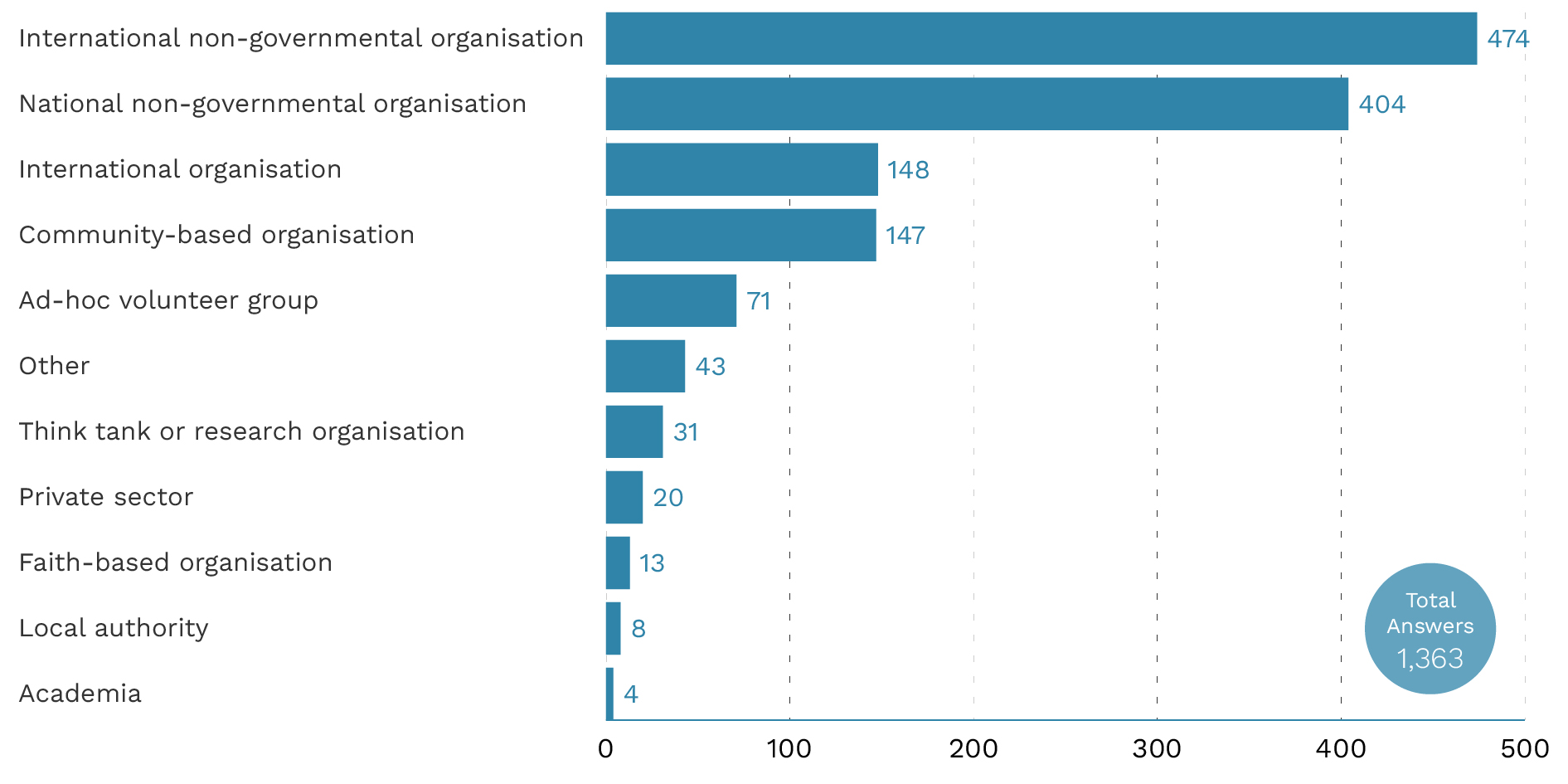

70% of individual Syrian respondents were under the age of 44, with the largest group (35%) between the ages of 35 and 44. The sample group was relatively balanced in terms of gender, with 291 women, 287 men, and 18 preferring not to say.

Figure 7: Gender of individual Syrian respondents

3.2. Civic Space and Political Processes

To ensure that respondents only answered questions relevant to their experiences, this section of the survey used skip logic to provide different questions to CSO respondents and individual Syrians. Individual Syrians were asked three questions concerning local decision-making and the role of civil society and the international community in the humanitarian response to the crisis in Syria, while CSO respondents were asked about specific challenges their organisations had faced as well as changes in the operational environment over the past 12 months. This section also included questions relating to the earthquakes that struck Türkiye and Syria in February 2023. Following these, a final set of questions asked all respondents about how they felt the role of civil society in the response to the crisis in Syria might be strengthened.

3.2.1. Questions for Individual Syrians

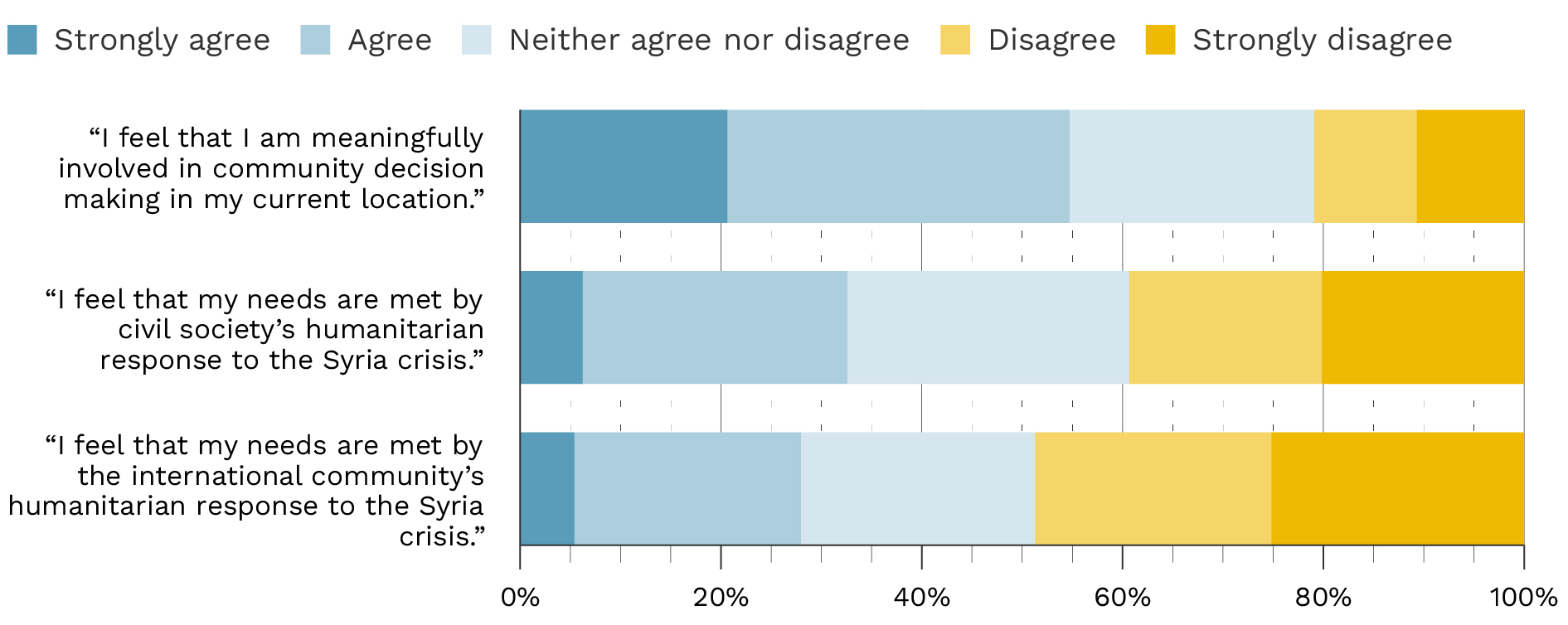

Respondents not affiliated with CSOs were asked to rate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with three statements relating to local decision-making and the humanitarian response to the Syria crisis. Over half of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they are meaningfully involved in community decision-making in their current location, but only around a third agreed or strongly agreed that their needs are met by both civil society’s and the international community’s humanitarian response to the Syria crisis.

Figure 8: Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with the following statements

Responses to these questions showed some slight differences depending on location, with respondents in Syria and Jordan expressing stronger agreement with the statements concerning the Syria response than those in Türkiye. Indeed, 40% of respondents in Türkiye “strongly disagreed” that their needs are met by civil society’s humanitarian response to the Syria crisis, and 44% “strongly disagreed” that their needs are met by the international community’s humanitarian response. This compared to 22% and 23%, respectively, of respondents in Syria, and 12% and 13%, respectively, of respondents in Jordan. However, it must be noted that the sample size for all countries other than Syria and Jordan was below 100 — further research into the opinions of Syrians in Türkiye may be needed to verify this finding, as well as to dig deeper into its causes.

3.2.2. Questions for CSOs

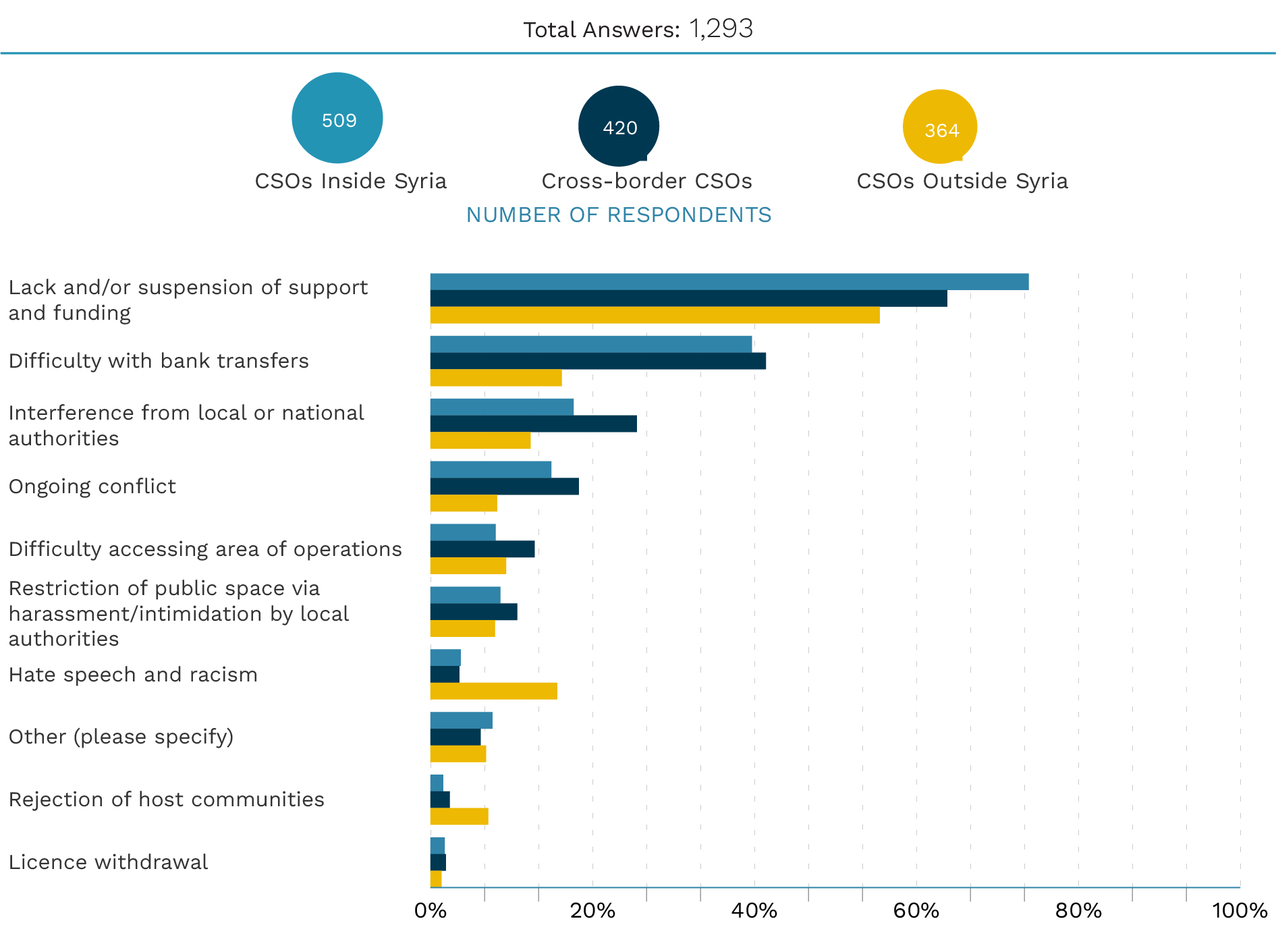

Figure 9: What are the most important challenges that your organisation has faced in the past 12 months? (select up to three)

CSO respondents were initially asked to outline the challenges faced by their organisations over the past 12 months. The most commonly chosen responses concerned funding, with “suspension of support and funding” and “bank transfers” selected by 65% and 34% of CSO respondents, respectively. “Interference from local or national authorities” was the third most chosen response overall, selected by 19% of CSO respondents. Notably, however, 25% of cross-border CSOs chose this option, compared with 15% of other CSO respondents. For CSOs outside Syria, “hate speech and racism” was the third most chosen option, selected by 16% compared to 4% of other CSO respondents. Notably, 23% of CSOs operating outside Syria said that their organisations had not faced any challenges in the past 12 months, while this figure was 10% and 8% for CSOs inside Syria and cross-border CSOs, respectively.

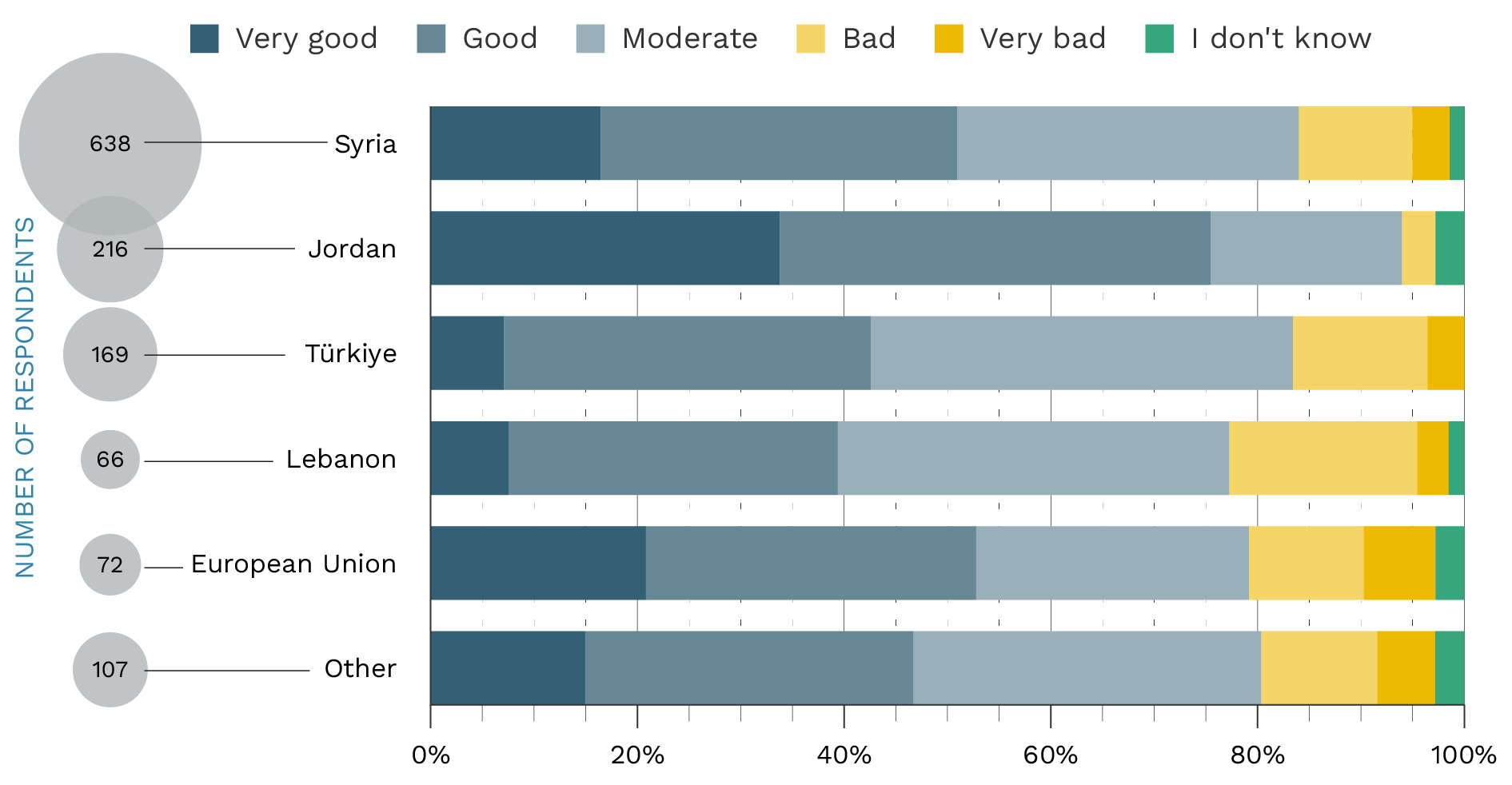

Figure 10: How would you rate the general operational environment for civil society in your country of operations?[1]

CSO respondents were then asked about the general operational environment for civil society in their country of operations, and how this had changed over the past 12 months. Over half of respondents rated the operational environment as “good” or “very good,” although these numbers varied by country. 78% of respondents in Jordan rated the general operational environment as “good” or “very good,” compared with 52% in Syria, 43% in Türkiye, and 40% in Lebanon.

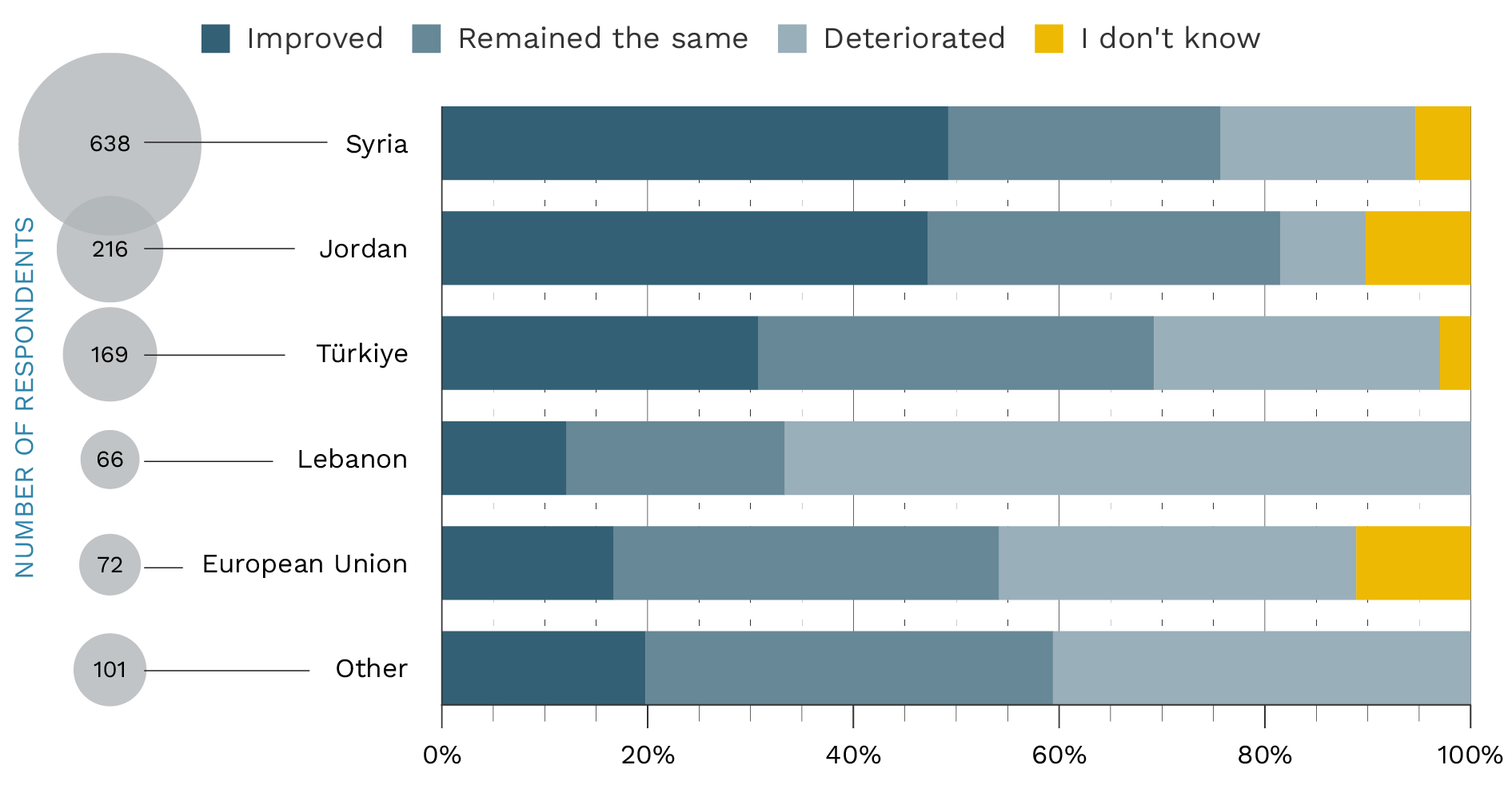

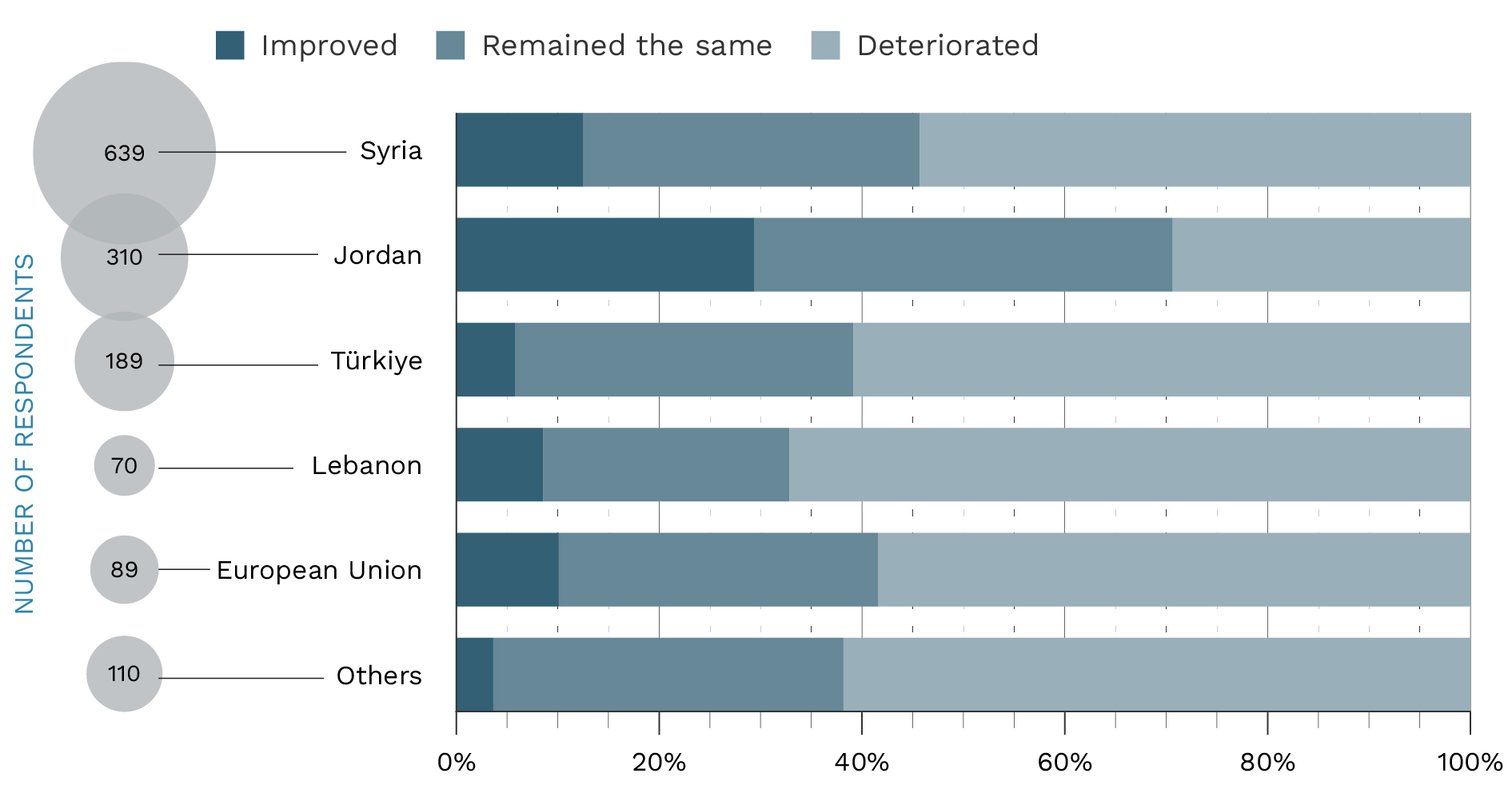

Figure 11: How has the general operational environment in your country of operations changed in the past 12 months?

Almost 50% of CSO respondents in Syria said that the general operational environment had improved, while 47% of CSO respondents in Jordan also said that the general operational environment had improved. By contrast, two-thirds of CSO respondents in Lebanon said that the operational environment had deteriorated. Respondents in Türkiye were more evenly split, with just under a third saying the operational environment had improved, a third saying it had remained the same, and a third that it had deteriorated.

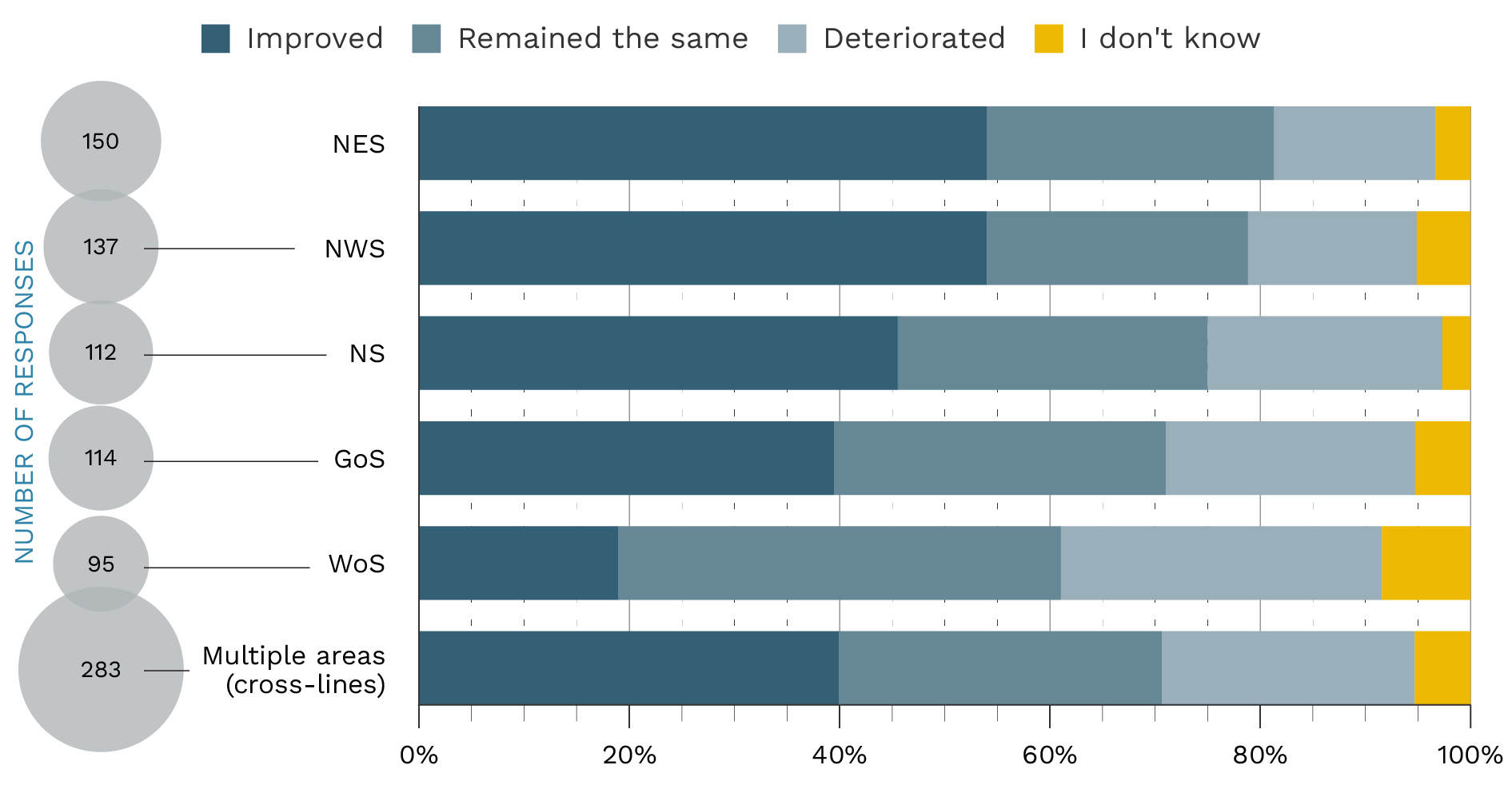

Figure 12: How has the general operational environment in your country of operations changed in the past 12 months? (By area of Syria)

There were some small differences between responses across the different areas of control in Syria. Over 50% of respondents operating in northeast and northwest Syria said that operational conditions had improved, compared with 39% of respondents operating in Government of Syria-controlled areas. Respondents who indicated that they work across the whole of Syria were most likely to say conditions had deteriorated (31%).

Figure 13: What factors have led to an improvement in the general operational environment for civil society in your country of operations in the last 12 months?

Respondents who indicated that the general operational environment had improved were then asked to choose the reasons for this. The most cited response was “better cooperation between civil society organisations,” selected by 56% of respondents, followed by a “better security environment” (42% of respondents), “increased funding” (24% of respondents) and “increased international coordination and support” (23% of respondents). The high number of respondents emphasising that better cooperation between CSOs has led to an improvement in the operational environment speaks to findings from the in-country consultations, particularly in Lebanon, where participants highlighted the need for fostering partnerships and supporting NGO fora and networks (see: Section 2).

Figure 14: What factors have led to a deterioration in the general operational environment for civil society in your country of operations in the last 12 months?

Of the respondents who indicated a deterioration in operational conditions, 75% pointed to “reduced funding,” while 62% highlighted “economic conditions,” and 61% chose “decreased international support.” The “impact of the 2023 earthquakes” was chosen by 45% of respondents, while 38% cited “increased restrictions by governing authorities” and 37% cited “political changes.”

3.2.3. Response to the 2023 Earthquakes

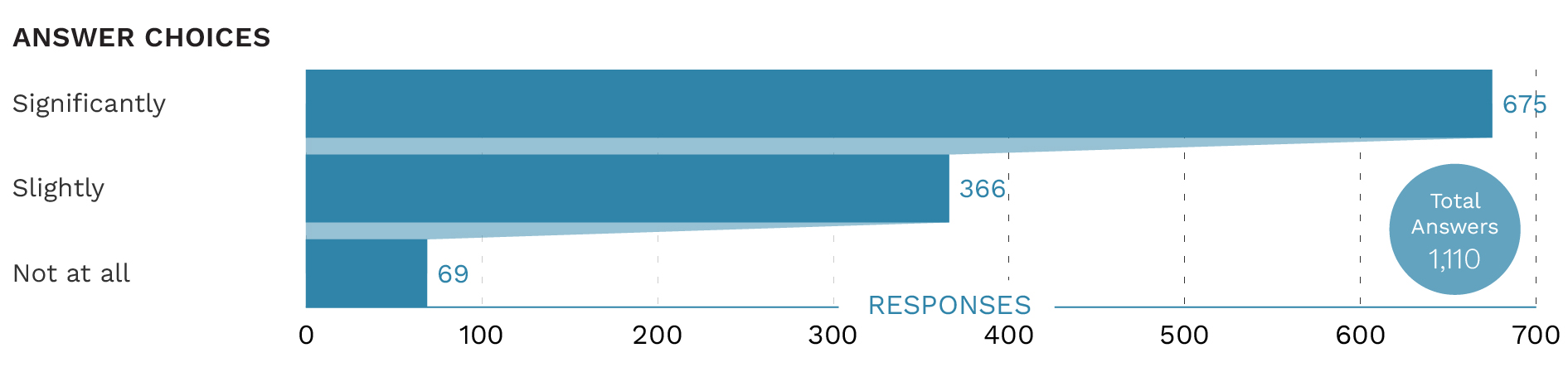

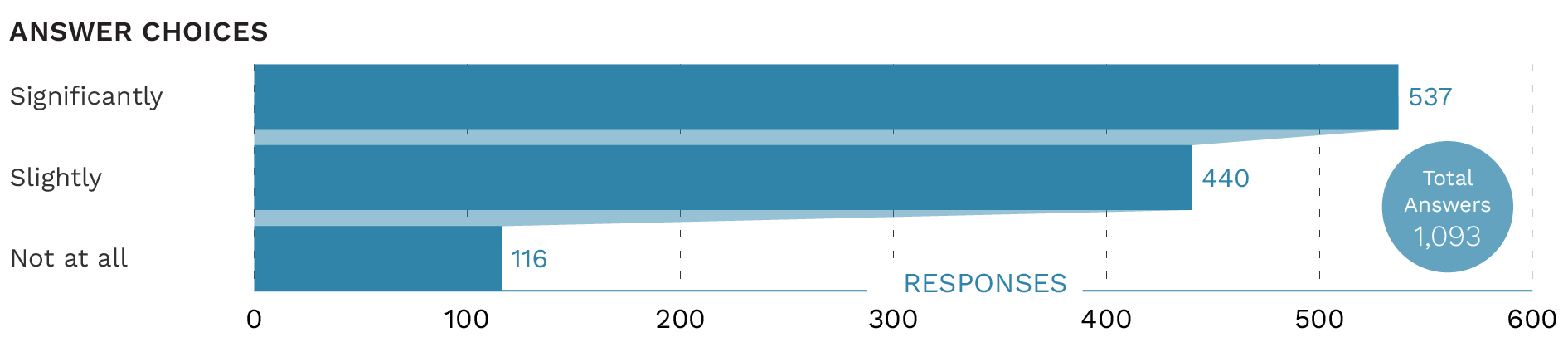

Figure 15: To what extent do you believe that the 2023 earthquakes have changed priorities for Syrian civil society?[2]

When asked about the extent to which the 2023 earthquakes changed priorities for Syrian civil society, over half of respondents (55%) said that they had “significantly” changed priorities, with 30% saying that priorities had changed “slightly.” Respondents were asked to explain their response in a free text-input question, in which they generally highlighted three key interconnected changes: a shift in funding away from early recovery efforts to an emergency response, a worsened humanitarian situation and an increase in needs, and an increase in the number of IDPs. Nevertheless, while respondents acknowledged that the earthquakes had an impact on priorities, the fundamental needs of the Syrian population remain the same, with basic needs such as food and shelter remaining critical in the areas affected by the earthquakes.

Syrian CSOs reported finding themselves focusing on the emergency response, looking to secure shelter, water, food, and treatment for the injured, setting back efforts to promote recovery in conflict-affected areas. Although the earthquake response opened discussions between Syrian interlocutors and international actors, basic needs such as food, shelter, and housing remain critical, especially in light of the ongoing crisis and economic inflation.

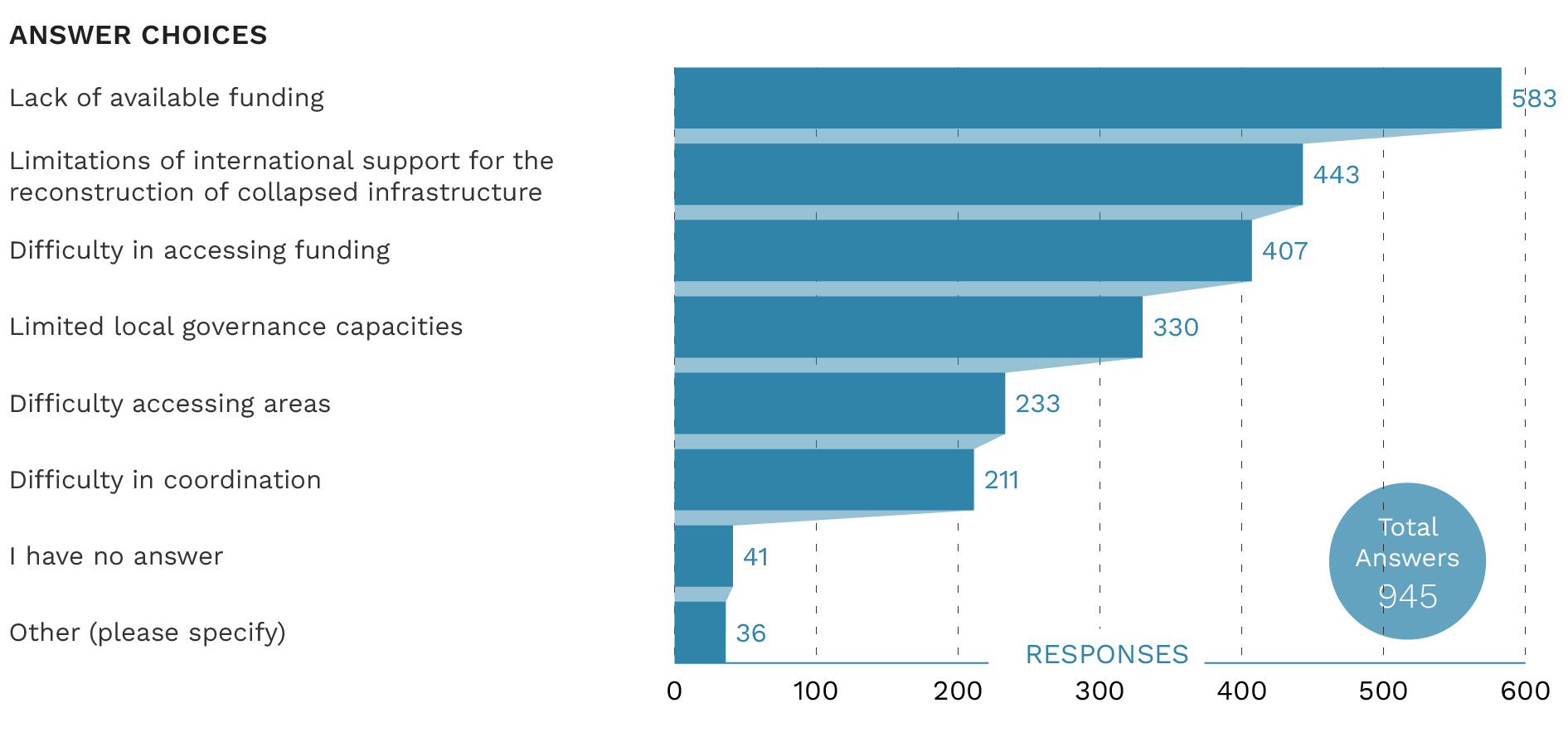

Figure 16: What do you believe are the main challenges affecting civil society following the 2023 earthquakes? (select up to three)

Of CSO respondents, 78% said that their organisation was involved in the response to the 2023 earthquakes — 90% of respondents working for CSOs inside Syria and cross-border were involved in the response, while 49% of CSOs outside Syria were also involved. These respondents were asked to select the key challenges affecting civil society after the 2023 earthquakes, with 62% choosing “lack of available funding,” 47% “limitations of international support for the reconstruction of collapsed infrastructure,” and 43% “difficulty in accessing funding.”

3.2.4. Questions for All Respondents

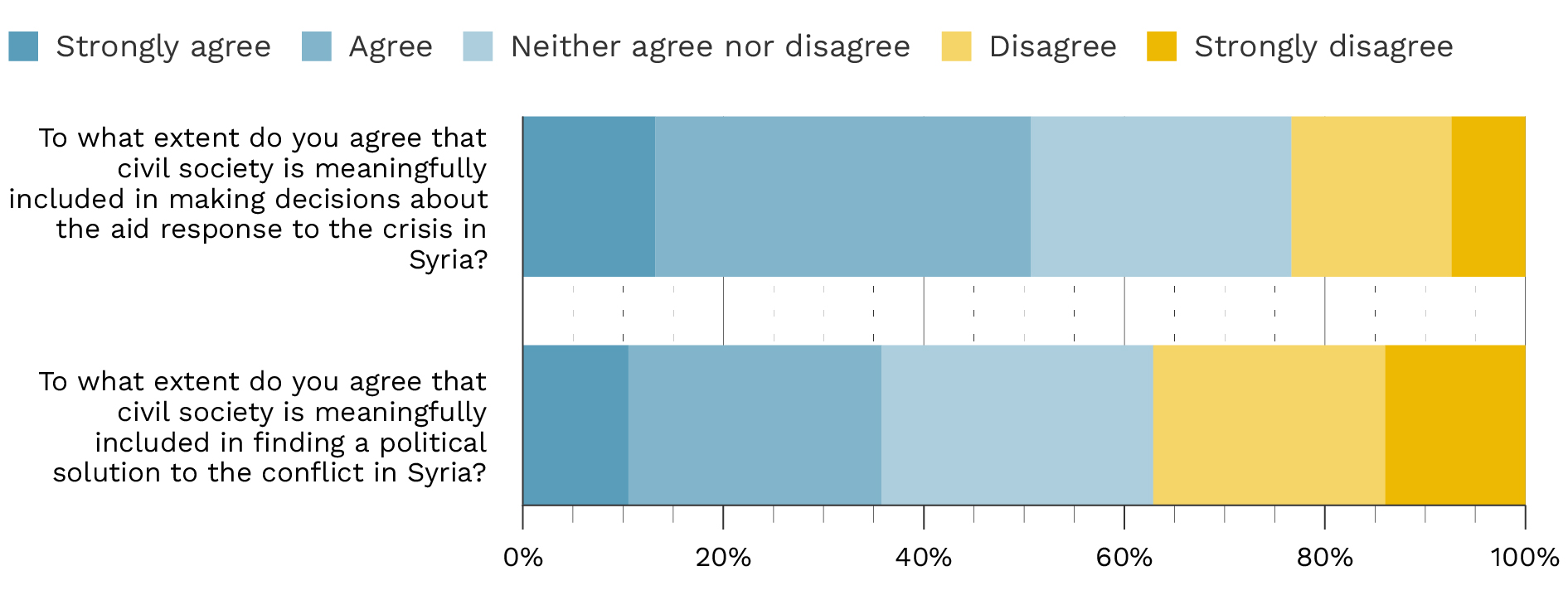

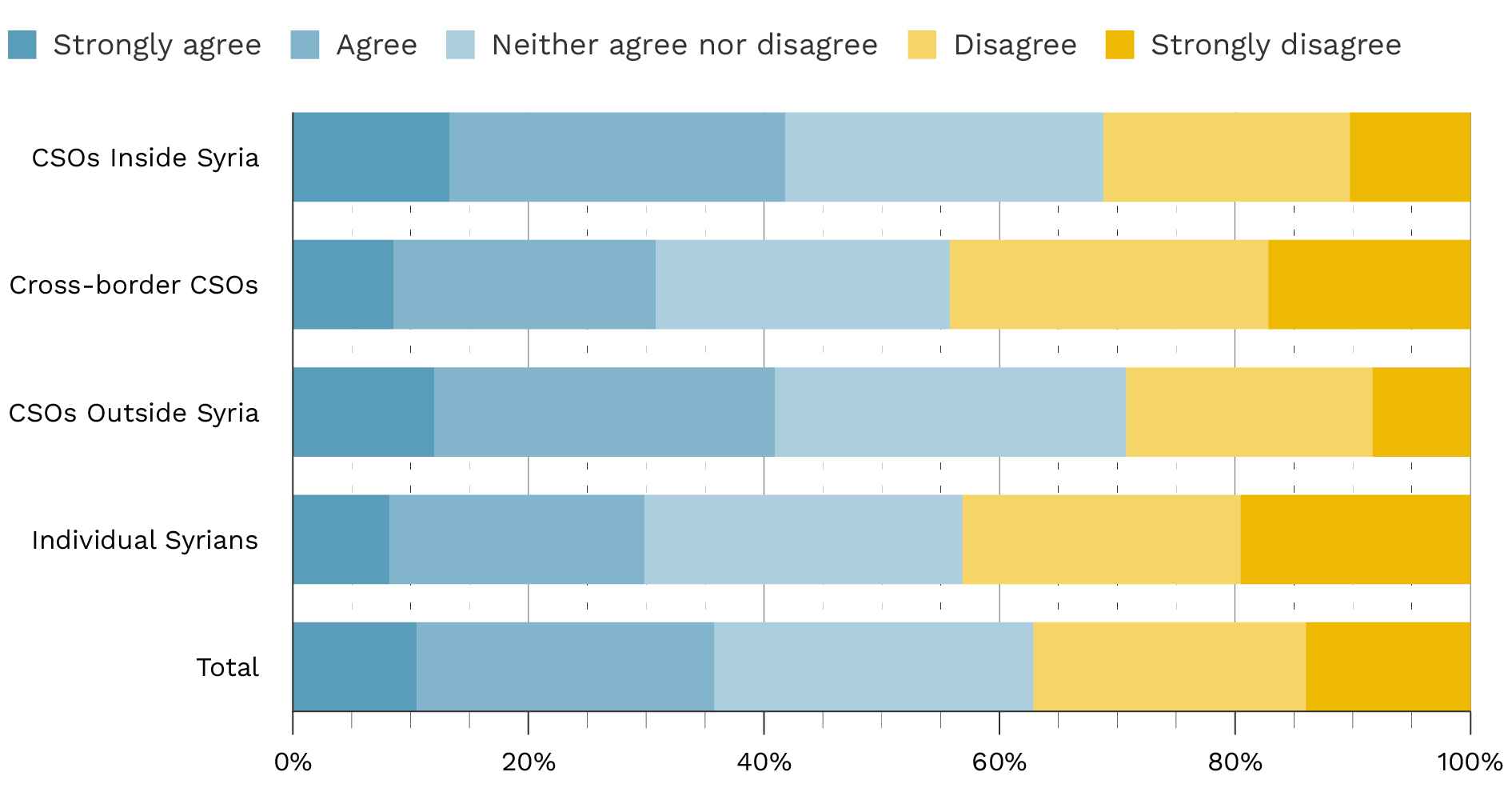

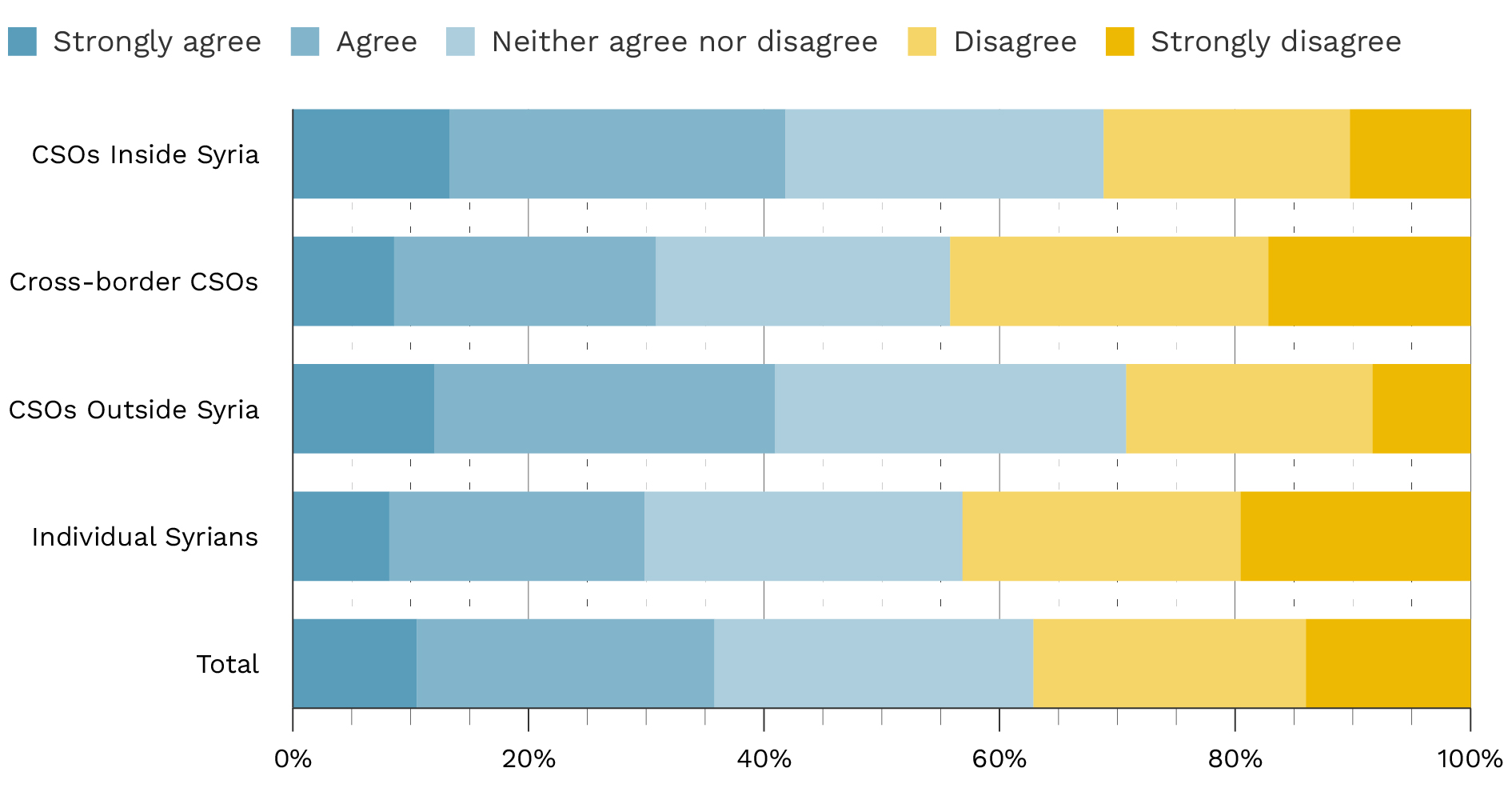

Figure 17: Civil society’s inclusion in decisions about the aid response and finding a political solution to the conflict in Syria

The next set of questions, concerning the role of civil society and how it should be strengthened, were answered by all respondents. While over 50% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that civil society is meaningfully included in making decisions about the aid response to the crisis in Syria, only around 35% agreed or strongly agreed that civil society is meaningfully included in finding a political solution to the crisis in Syria. Approximately a quarter of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed that civil society is meaningfully included in making decisions about the aid response, while over a third disagreed or strongly disagreed that civil society is meaningfully included in finding a political solution to the conflict in Syria. These results add to the voices of participants in the in-country consultations who called for localisation, the increased involvement of NGOs in programme design, and support for communication and dialogue programmes between civil and political actors (see: Section 2).

Figure 18: To what extent do you agree that civil society is meaningfully included in making decisions about the aid response to the crisis in Syria?

Individual Syrians agreed to a lesser extent than CSO respondents with the statement that civil society is meaningfully included in making decisions about the aid response to the crisis in Syria. 34% of individual respondents either strongly agreed or agreed with the statement, while 56% of CSO respondents strongly agreed or agreed. There were small differences depending on the type of organisation, with 48% of cross-border CSO representatives agreeing or strongly agreeing with the statement compared to 61% of other CSO respondents.

Figure 19: To what extent do you agree that civil society is meaningfully included in finding a political solution to the conflict in Syria?

There was a smaller difference between CSO respondents and individual Syrians regarding the extent to which they agree that civil society is meaningfully included in finding a political solution to the conflict in Syria. 30% of individual Syrians and 38% of CSO respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, while 38% of CSO respondents agreed. Again, there were differences based on the type of CSO, with 31% of cross-border CSO respondents agreeing or strongly agreeing with the statement compared to 41% of other CSO respondents.

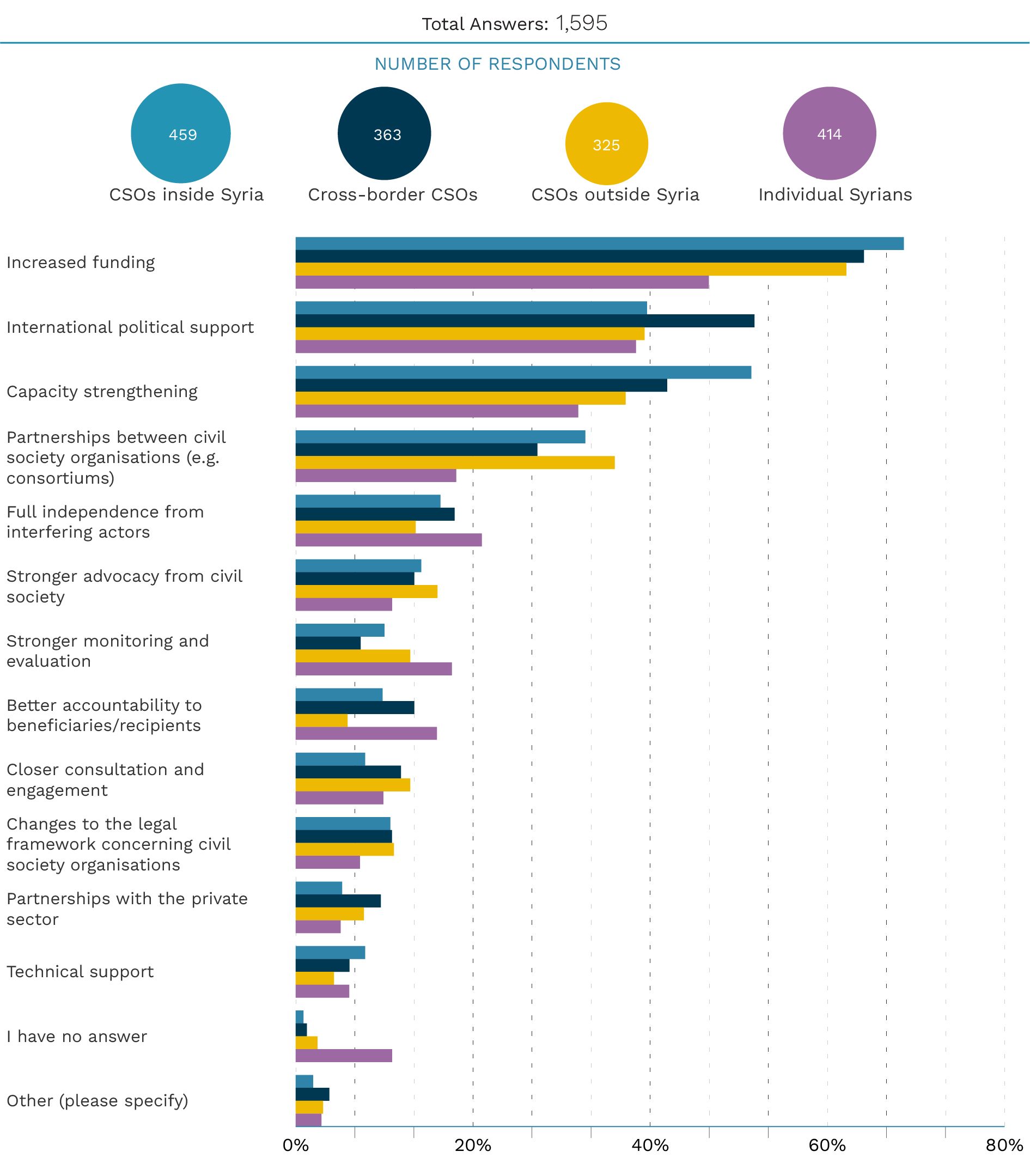

Figure 20: What is most needed to strengthen the role of civil society in the aid response to the crisis in Syria? (select up to three)

When asked about what is needed to strengthen the role of civil society in the aid response to the crisis in Syria, 60% of respondents selected “increased funding,” 42% selected “international political support,” and 41% selected “capacity strengthening.” These were the top three answers for both CSO and individual Syrian respondents, as well as all three types of CSO respondent. However, there were differences in the ordering of the top three between the different categories of respondent. 51% of respondents from CSOs inside Syria selected “capacity strengthening,” compared with 40% of other CSO types and 32% of individual Syrians. Furthermore, 52% of cross-border CSO respondents selected “international political support,” compared to 40% of other CSO respondents and 38% of individual Syrians.

Beyond the top three choices, 32% of CSO respondents chose “partnerships between civil society organisations (e.g. consortiums), compared to 18% of individual Syrians — in line with recommendations from the in-country consultations to prioritise partnership and collaboration between NGOs (see: Section 2). Individual Syrians also selected “full independence from interfering actors,” “stronger monitoring and evaluation,” and “better accountability to beneficiaries/recipients” more often than CSO respondents (21% vs 16%, 18% vs 10%, and 16% vs 10%, respectively).

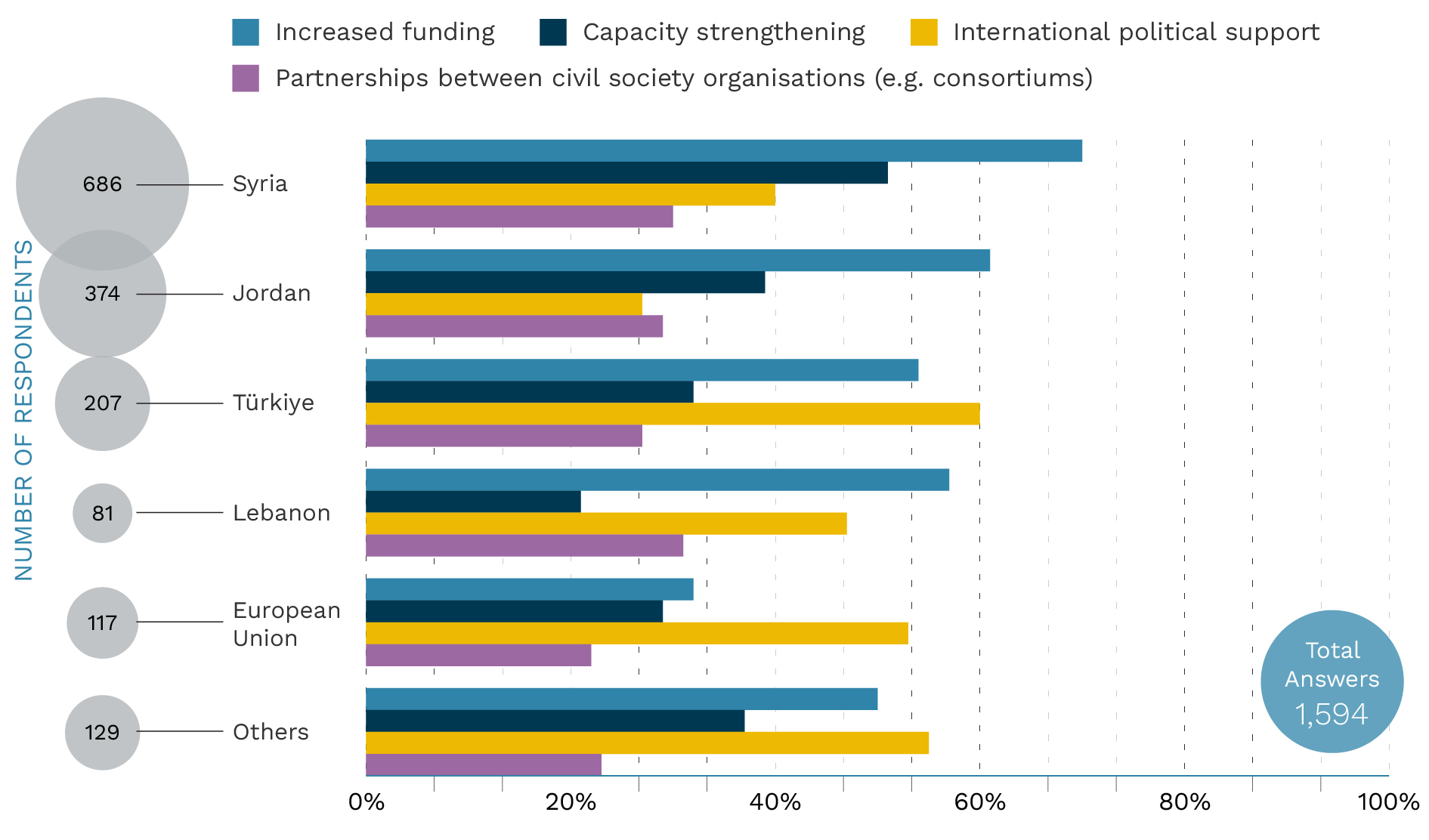

Figure 21: What is most needed to strengthen the role of civil society in the aid response to the crisis in Syria? (select up to three)

When compared by country, respondents in Türkiye, Lebanon, and the European Union chose “international political support” more often than those in Syria and Jordan, who instead selected “capacity strengthening” to a greater extent.

3.3. Basic Services in Syria

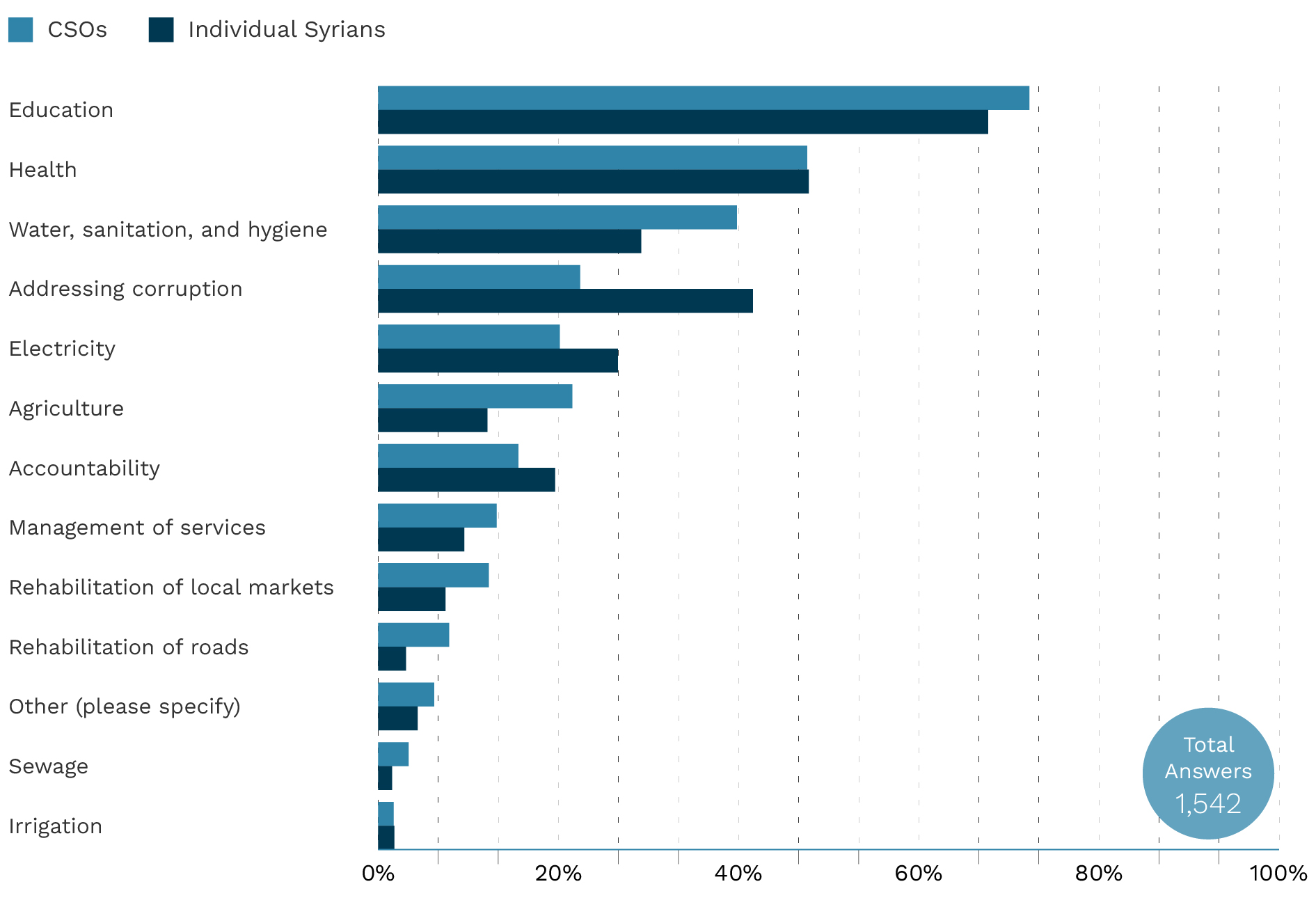

In this section of the survey, respondents were asked about priority sectors for work on improving basic services in Syria, as well as the challenges to improving basic services and the impact of the 2023 earthquakes. All respondents to the survey (both CSO and individual Syrians) were asked all questions in this section, and skip logic was only used for one question relating to the impact of the 2023 earthquakes. When asked about the priority areas for targeting basic services in Syria, “education” was the most commonly identified (selected by 71% of respondents), followed by “health” (48%), and “water, sanitation, and hygiene” (37%).

Figure 22: In your opinion, what should be the priority areas in projects targeting basic services in Syria? (select up to three)

While “education” and “health” were the top two priority areas identified by all respondents, the third most selected option for individual Syrians was “addressing corruption” (42%), and “water, sanitation, and hygiene” was the third most selected for CSO respondents (40%). “Addressing corruption” was selected by 22% of CSO respondents overall. CSO respondents also selected “agriculture” to a greater extent than individual Syrians (22% vs 12%), while individual Syrians selected electricity (27% vs 20%) and accountability (20% vs 16%) to a greater extent than CSO respondents. “Agriculture” was the fourth most common choice for CSO respondents inside Syria as well as cross-border CSOs, while “addressing corruption” was the fourth most common choice for CSO respondents outside Syria.

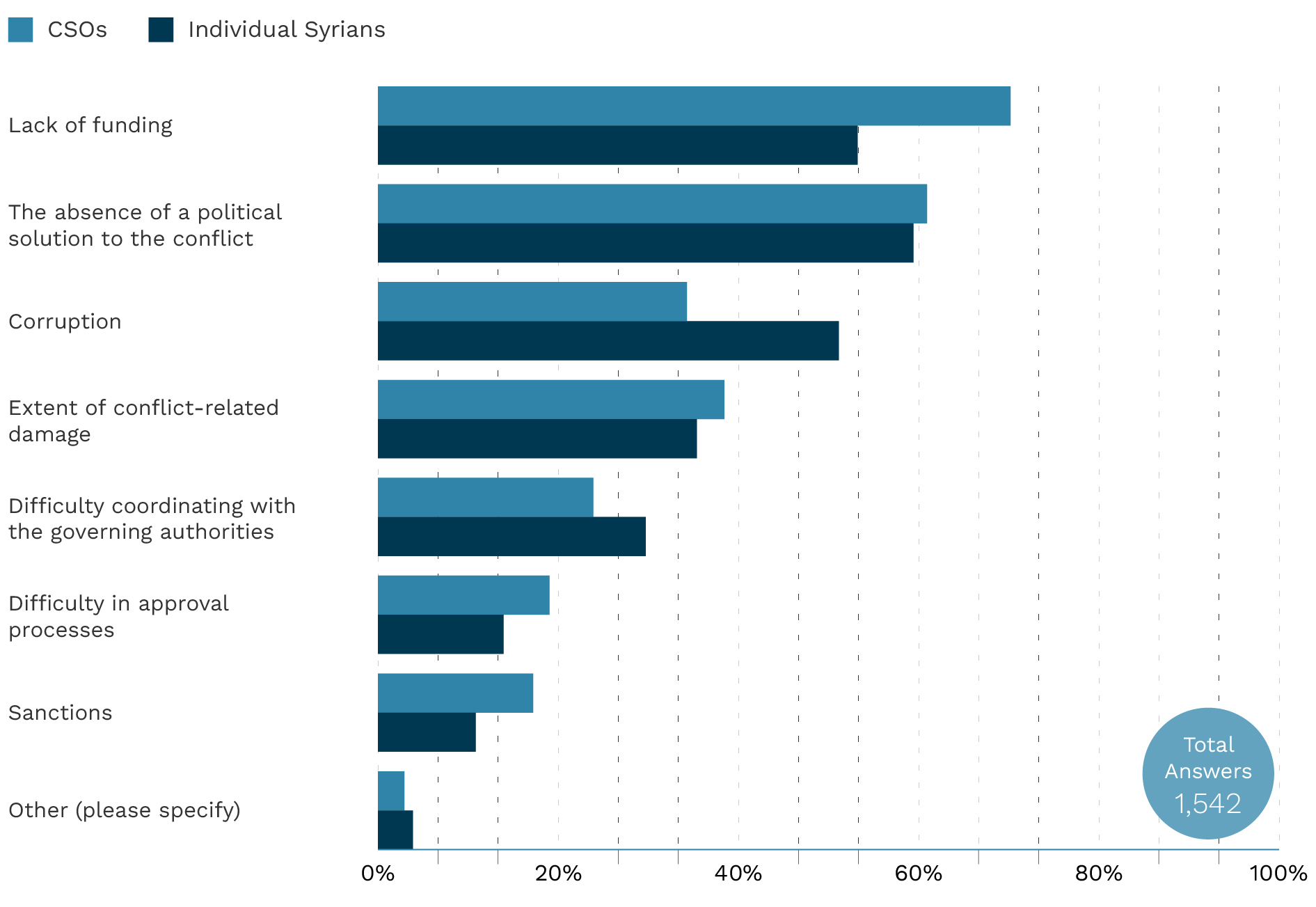

Figure 23: In your opinion, what are the main impediments to improving basic services in Syria? (select up to three)

When asked about the main impediments to improving basic services in Syria, the most selected were “lack of funding” (66%), “the absence of a political solution to the conflict” (61%), “corruption” (39%) and the “extent of conflict-related damage” (38%). The need for a political solution to the conflict as a prerequisite to addressing the root causes of Syria’s humanitarian crisis was also emphasised in the in-country consultations (see: Section 2), where participants stressed the importance of fully implementing UN Security Council Resolution 2254.

Differences can be seen in the responses of CSO respondents and individual Syrians to the question of impediments to improving basic services. 70% of CSO respondents chose “lack of funding,” compared with 53% of individual Syrians. Although CSO respondents and individual Syrians chose “the absence of a political solution to the conflict” at roughly the same rate, this was the most chosen option for individual Syrians. Individual Syrians also selected “corruption” at a higher rate than CSO respondents; it was the third most chosen, with 51% selecting this option against 34% of CSO respondents (for whom it was the fourth most chosen response). Notably, “corruption” was the third most chosen option for CSOs operating inside Syria (37%), slightly ahead of “extent of conflict-related damage” (35%).

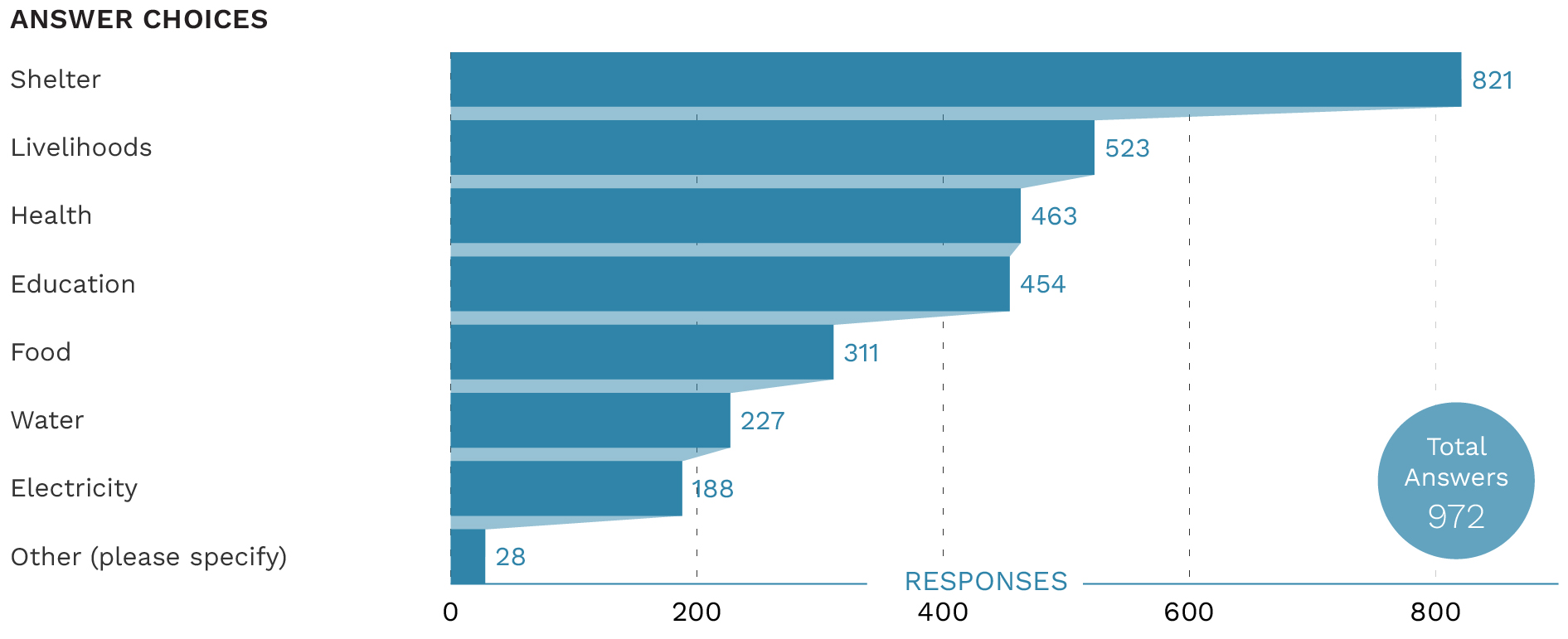

Figure 24: To what extent did the 2023 earthquakes impact basic services in your area?[3]

All respondents were then asked whether basic services had been affected in their area as a result of the 2023 earthquakes, with those saying that they had been “significantly” or “slightly” affected further asked about which services had been most impacted. Around two-thirds of respondents said that services had been impacted “significantly” or “slightly,” with “shelter” the most chosen response (85%), followed by “livelihoods” (54%), “health” (48%), and “education” (47%).

Figure 25: Which services were most impacted following the 2023 earthquakes?

3.4. Early Recovery and Livelihoods

In this section of the survey, respondents were asked five questions pertaining to early recovery efforts in Syria and access to livelihoods, both inside Syria and in neighbouring countries. All respondents to the survey were asked all questions in this section, with skip logic used to allow respondents to explain their answer to the question on changes in access to jobs and livelihoods.

Figure 26: How has access to jobs and livelihoods for Syrians changed over the past 12 months in your country of work?

When asked how access to jobs and livelihoods for Syrians had changed over the past 12 months, 13% of respondents said that it had improved, 32% that it had remained the same, and 47% that it had deteriorated, pointing to the need for early recovery and employment-creation programming emphasised in the in-country consultations (see: Section 2).

Across the different country contexts, only in Jordan did a majority of respondents say that access to jobs and livelihoods for Syrians had improved or remained the same over the past 12 months. Jordan stands out as the only country where over a quarter of respondents said that access to jobs and livelihoods had improved. By contrast, 61% of respondents in Türkiye, 58% in Lebanon, and 54% in Syria said that access to jobs and livelihoods had deteriorated.

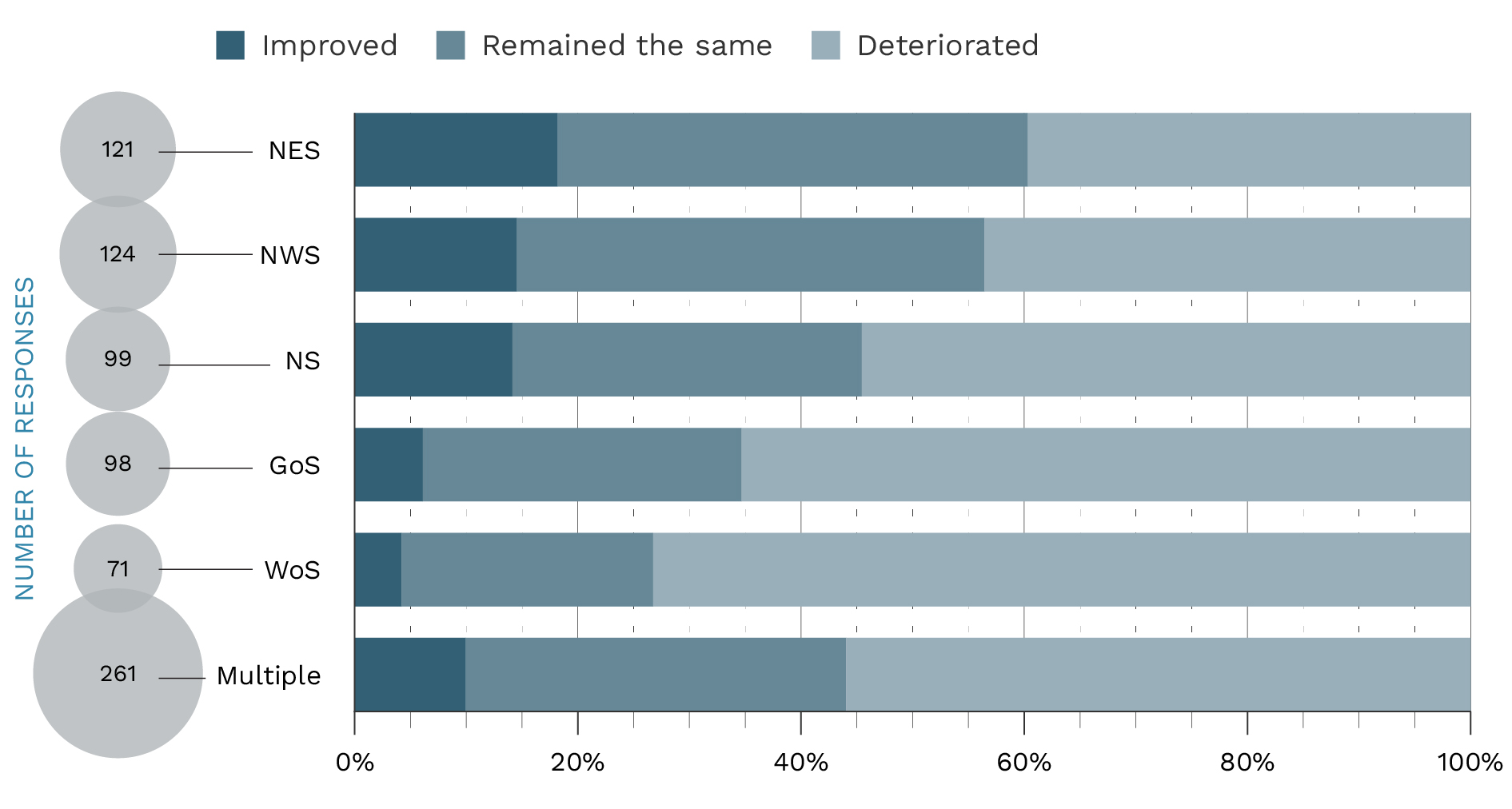

Figure 27: How has access to jobs and livelihoods for Syrians changed over the past 12 months in your country of work? (inside Syria)

In northeast and northwest Syria, a majority of respondents said that access to jobs and livelihoods had either improved (18% and 15%, respectively) or remained the same (42% and 42%, respectively). Across all other contexts, a majority of respondents said that access to jobs and livelihoods had deteriorated, with respondents indicating that they operate across the whole of Syria choosing “deteriorated” at the highest rate (73%).

Figure 28: In your opinion, what are the main reasons for the improvement in access to jobs and livelihoods? (select up to three)

Respondents who said that access to jobs and livelihoods had improved were asked to select the main reasons for this. The most chosen response was “increased international support” (74%), followed by “better education and training” (55%), and “rehabilitated infrastructure” (39%).

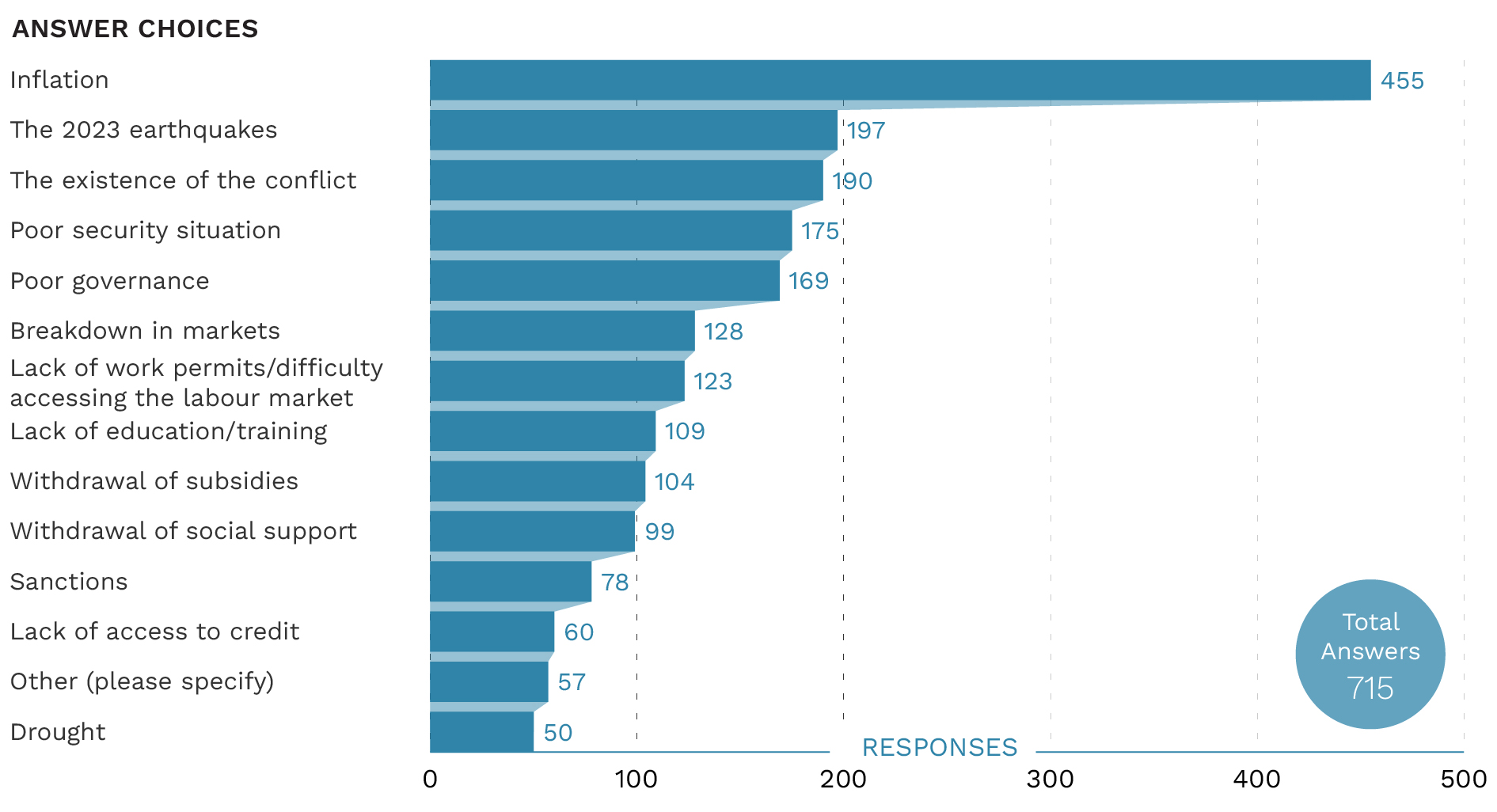

Figure 29: In your opinion, what are the main reasons for the deterioration of access to jobs and livelihoods? (Choose up to three options)

Respondents who said that access to jobs and livelihoods had deteriorated overwhelmingly chose “inflation” as a main reason, selected by 64% of respondents and pointing to the long-running economic crisis in Syria as well as global inflationary pressures that are particularly impacting countries in the region. The second most chosen reason was “the 2023 earthquakes” (28%), followed by “the existence of the conflict” (27%), “poor security situation” (24%), and “poor governance” (24%).

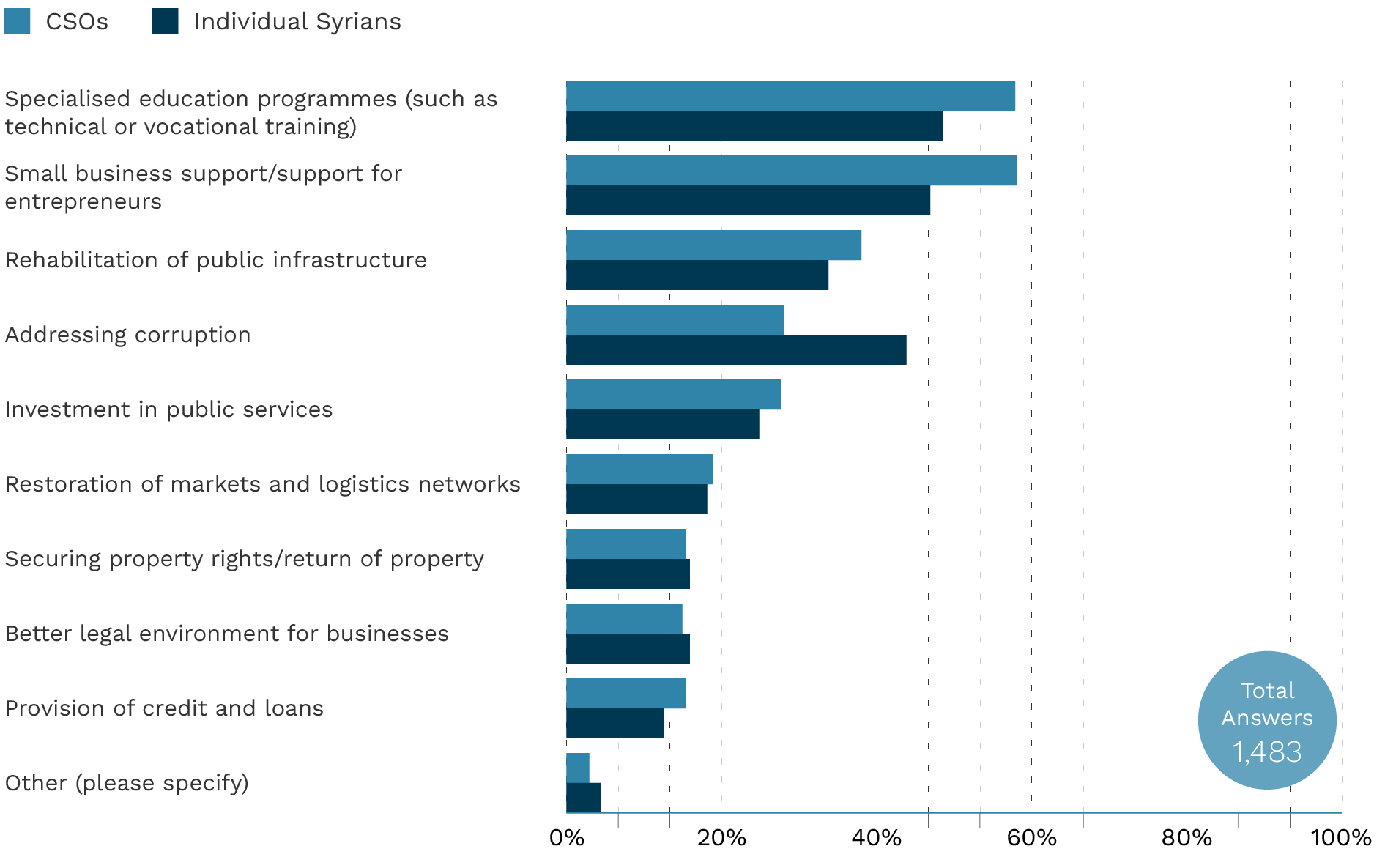

Figure 30: In your opinion, what is the best way to improve access to jobs and livelihoods in Syria? (select up to three)

When asked about the best ways to improve access to jobs and livelihoods in Syria, a majority of respondents selected either “specialised education programmes” and/or “small business support/support for entrepreneurs” (56% each). The third most selected response was “rehabilitation of public infrastructure” (37%), followed by “addressing corruption” (32%), and “investment in public services” (27%). When responses of CSOs and individual Syrians are compared, we see that while both groups selected “specialised education programmes” and “small business support/support for entrepreneurs” the most, “addressing corruption” was the third most selected response for individual Syrians (44%), while this was the fifth most selected for CSO respondents (28%).

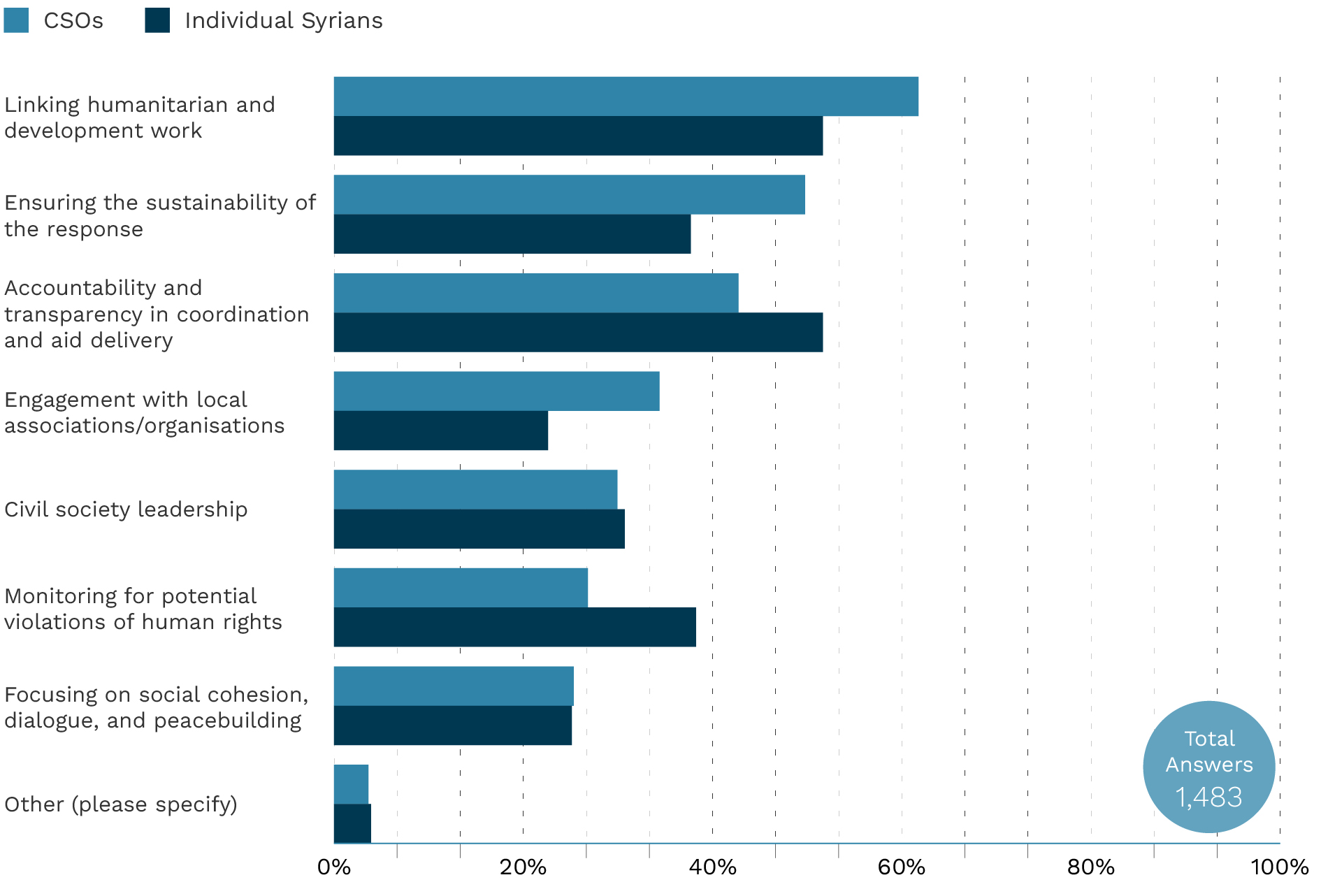

Figure 31: What are the most important elements that donors should prioritise to enhance the effectiveness of recovery efforts in Syria? (select up to three)

When asked about the most important elements for donors to prioritise in recovery efforts in Syria, a majority of respondents (59%) chose “linking humanitarian and development work” — a core component of “nexus” programming in Syria that was also highlighted in the in-country consultations as a pathway to ensuring social cohesion and equitable access to services, livelihoods, and education for displaced persons in particular (see: Section 2). This was followed by “ensuring the sustainability of the response” (47%) and “accountability and transparency in coordination and aid delivery” (45%).

Individual Syrian respondents chose “accountability and transparency in coordination and aid delivery” and “linking humanitarian and development work” at equal rates (52%). Their third most chosen response was “monitoring for potential violations of human rights” (38%), which was only the sixth most chosen response for CSO respondents (27%). In line with recommendations for greater localisation in the Syria response shared by participants of the in-country consultations (see: Section 2), “engagement with local associations/organisations” was the fourth most selected response for CSO respondents (34%), compared to 22% of individual Syrians (seventh most selected response). CSOs inside Syria selected “engagement with local associations/organisations” at a higher rate than other CSO respondents (40% vs 31%), while CSOs working inside Syria (including cross-border CSOs) selected “linking humanitarian and development work” and “ensuring the sustainability of the response” at higher rates than CSOs outside Syria (67% vs 50%, and 55% vs 37%, respectively), perhaps indicating the perception of more challenging long-term conditions from inside Syria than outside it.

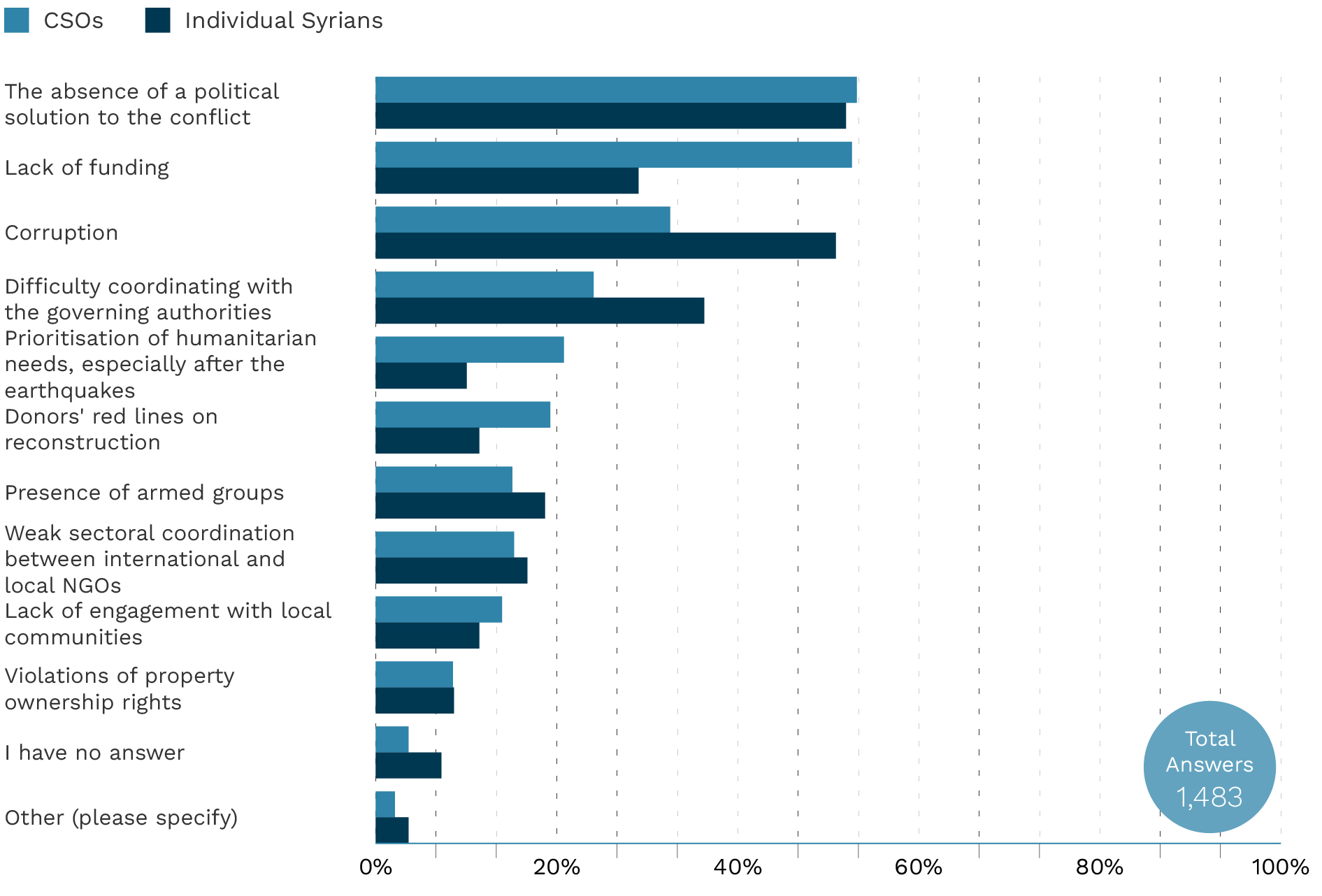

Figure 32: What are the main obstacles to the success of projects seeking to restore services and livelihoods in conflict-affected areas in Syria? (select up to three)

Respondents selected “the absence of a political solution to the conflict” as the main obstacle to the success of projects seeking to restore services and livelihoods in conflict-affected areas in Syria (53%), followed by “lack of funding” (47%) and “corruption” (37%). When comparing between CSO respondents and individual Syrians, however, we see a different ranking. While “the absence of a political solution to the conflict” was selected the most by both groups and at similar rates (53% and 52%, respectively), the second most chosen option for CSO respondents was “lack of funding” (53%), while for individual Syrians it was “corruption” (51%). “Lack of funding” was the fourth most selected response for individual Syrians (29%), while “corruption” was the third most selected response for CSO respondents (33%). The third most selected response for individual Syrians was “difficulty coordinating with the governing authorities” (36%), which was the fourth most chosen response for CSO respondents (24%).

Interestingly, respondents from CSOs working with Syrians outside Syria selected “difficulty coordinating with the governing authorities” at a much higher rate (35%) than other CSO respondents (20%), while this group also selected “lack of funding” at a much lower rate (33%) than other CSO respondents (60%).

3.5. Displacement and Durable Solutions

The final set of questions, concerning displacement and durable solutions to displacement, was split into two: one set asked about refugees and the other about IDPs. While the circumstances of these two groups of people differ, the results show that respondents believe both groups face similar challenges — with a political solution to the conflict the central prerequisite to facilitating safe, dignified, and voluntary returns.

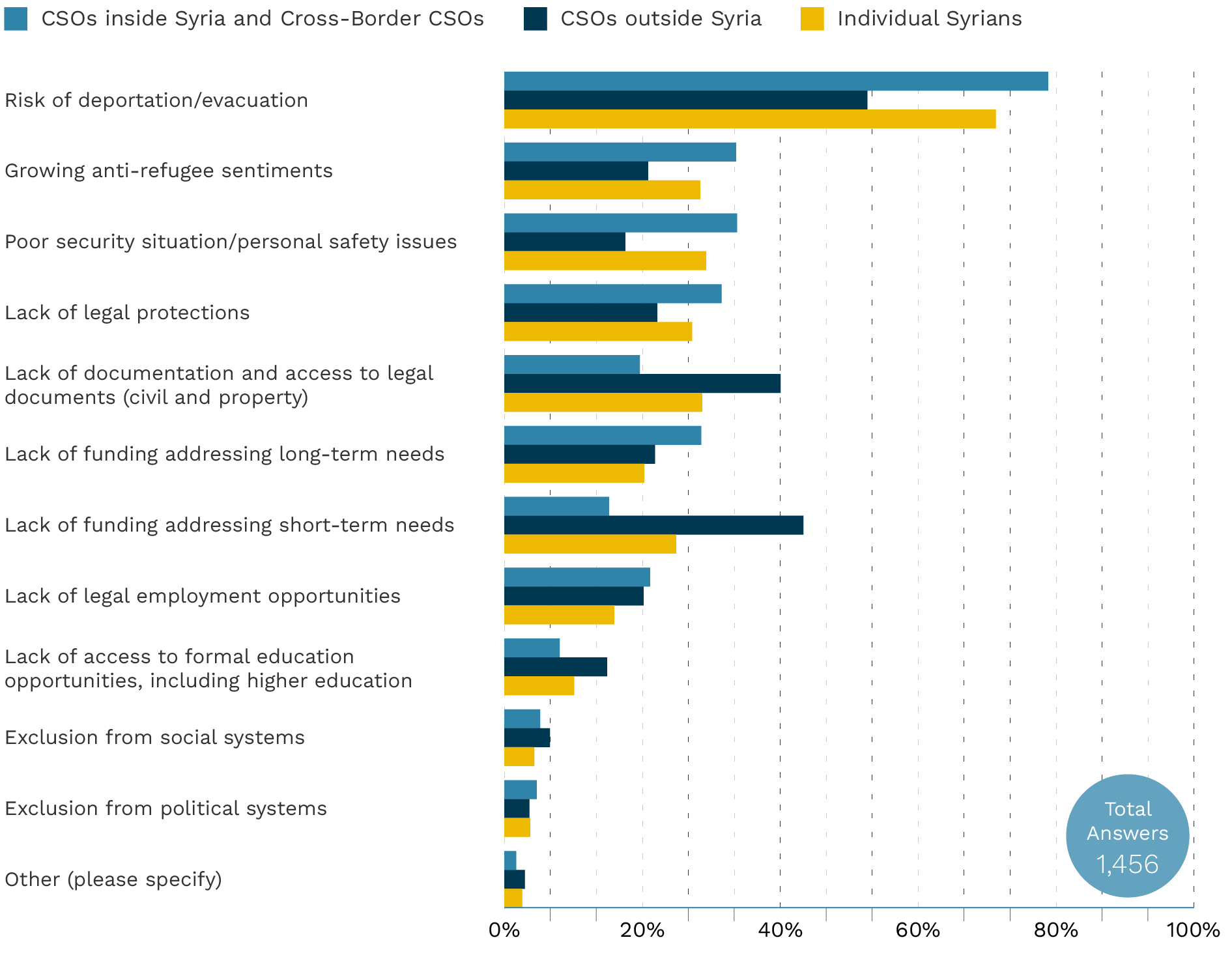

3.5.1. Refugees

When asked about the main challenges faced by Syrian refugees in host countries, a clear majority (72%) of respondents selected “risk of deportation/evacuation.” “Growing anti-refugee sentiments,” “poor security situation/personal safety issues,” and “lack of legal protections” were selected roughly equally — by around 30% of respondents — while “lack of documentation and access to legal documents (civil and property),” “lack of funding addressing long-term needs,” and “lack of funding addressing short-term needs” were selected by around a quarter of respondents.

Figure 33: In your opinion, what are the main challenges faced by Syrian refugees in host countries? (select up to three)

Notably, while cross-border CSOs and CSOs working inside Syria responded similarly, CSOs working with Syrians outside Syria — those most likely to be working with refugees — provided a different ranking. 53% of CSO respondents working outside Syria selected “risk of deportation/evacuation,” followed by 43% selecting “lack of funding addressing short-term needs,” and 40% selecting “lack of documentation and access to legal documents (civil and property).”

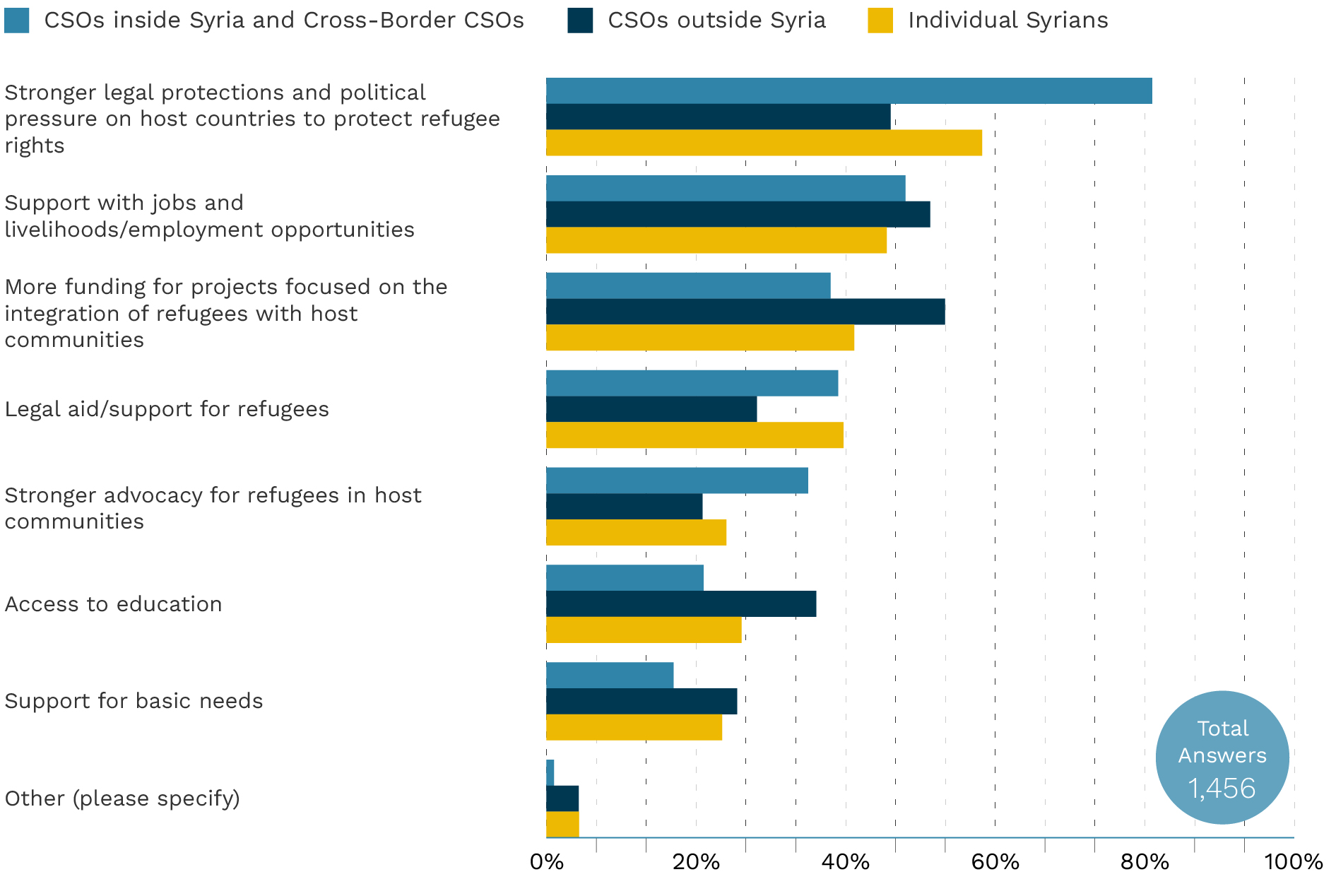

Figure 34: In your opinion, what is most needed to support Syrian refugees in host countries? (select up to three)

When asked what is most needed to support Syrian refugees in host countries, 68% of respondents answered “stronger legal protections and political pressure on host countries to protect refugee rights,” 48% with “support with jobs and livelihoods/employment opportunities,” and 42% with “more funding for projects focused on the integration of refugees with host communities.” Once again, however, respondents from CSOs working with Syrians outside Syria answered in a slightly different order: the most chosen answer was “more funding for projects focused on the integration of refugees with host communities” (53%), followed by “support with jobs and livelihoods/employment opportunities” (51%), and “stronger legal protections and political pressure on host countries to protect refugee rights” (46%).

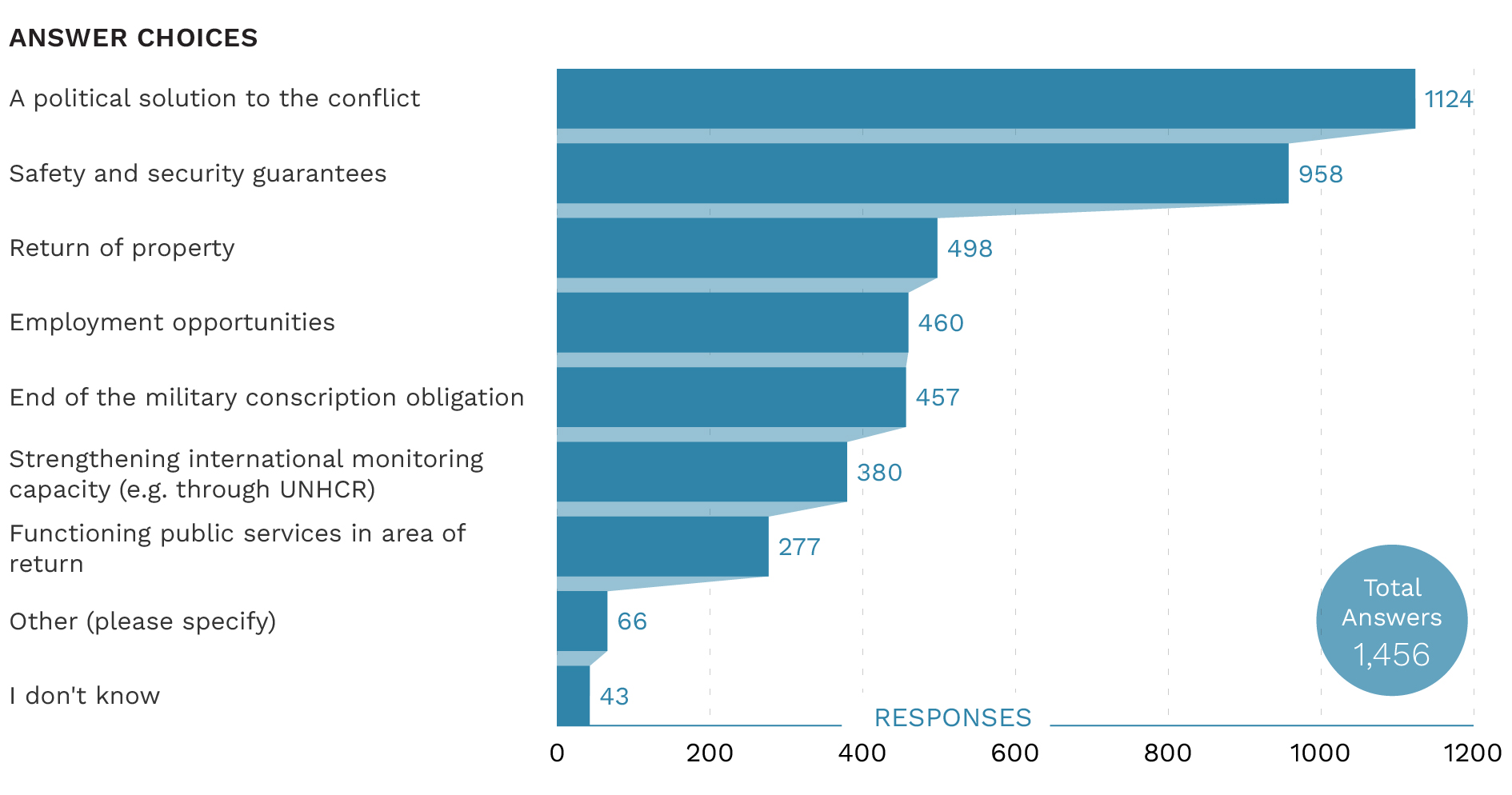

Figure 35: In your opinion, what would be needed to facilitate the safe, dignified, and voluntary return of refugees to Syria?

On what would be needed to facilitate the safe, dignified, and voluntary return of refugees to Syria, respondents showed less variation: across all categories of respondent, the most selected option was “a political solution to the conflict” (77%), followed by “safety and security guarantees” (66%). “Return of property” was the third most selected option across all categories (34%) followed by “employment opportunities” and “end of the military conscription obligation” (31% each). The almost universal agreement that a political solution to the conflict is needed to facilitate refugee return supports the in-country consultations’ emphasis that absent a political solution, repatriation would be impossible.

3.5.2. Internally Displaced Persons

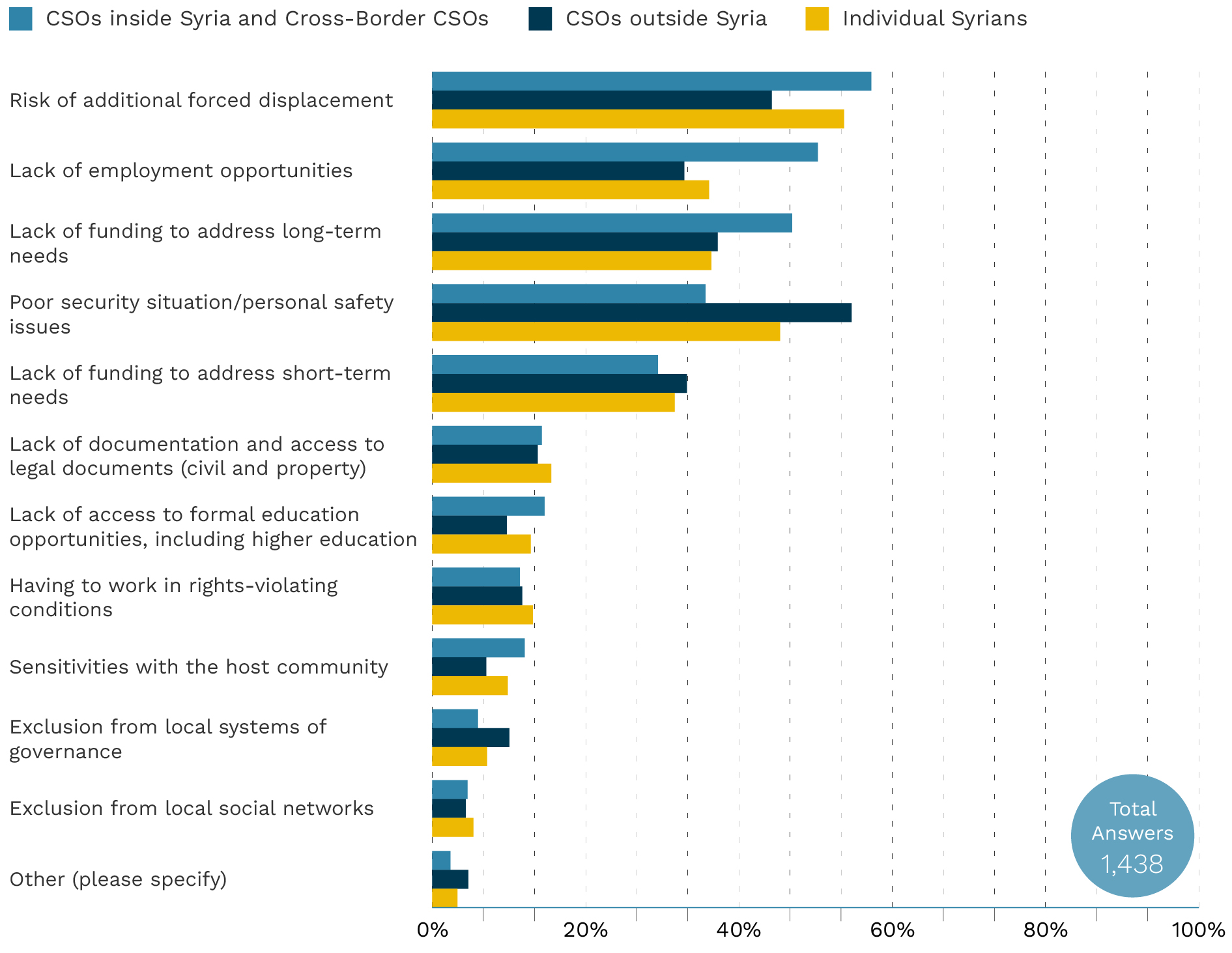

Figure 36: In your opinion, what are the main challenges facing Syrians displaced internally within Syria? (select up to three)

The final set of questions concerned the challenges faced by IDPs in Syria. When asked about the main challenges faced by this group of people, respondents chose “risk of additional forced displacement” (54%), followed by “lack of employment opportunities” (43%), “lack of funding to address long-term needs” (42%), and “poor security situation/personal safety issues” (41%). These results were similar across all categories of respondent, although CSO respondents outside Syria as well as individual Syrians pointed to “poor security/personal safety issues” more strongly (55% and 45%, respectively) than other CSO respondents (36%).

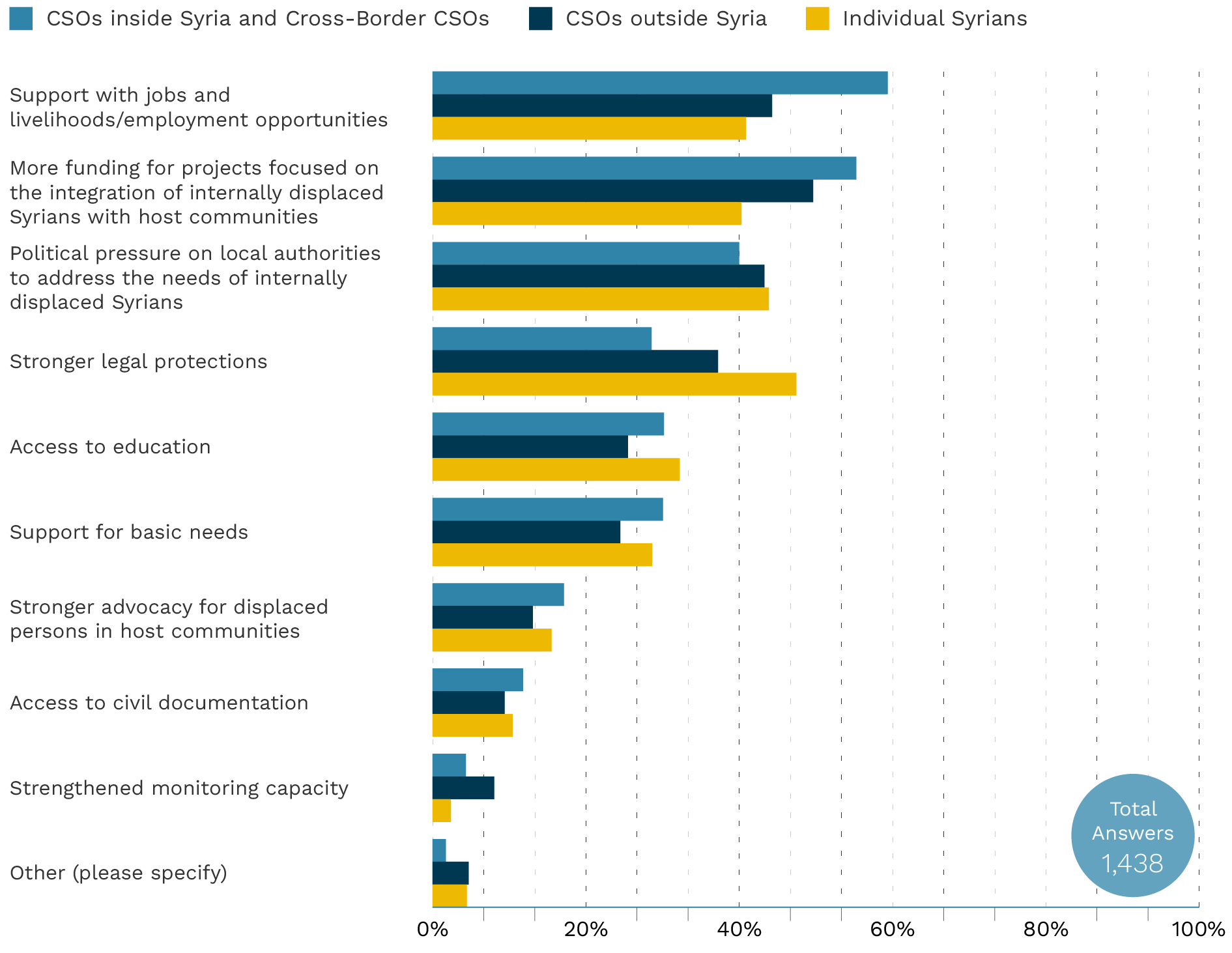

Figure 37: In your opinion, what is most needed to support internally displaced Syrians? (select up to three)

On what is most needed to support internally displaced Syrians, CSO respondents most frequently selected “support with jobs and livelihoods/employment opportunities” (55%) and “more funding for projects focused on the integration of internally displaced Syrians with host communities” (54%), followed by “political pressure on local authorities to address the needs of internally displaced Syrians” (41%). By contrast, individual Syrians selected “stronger legal protections” (47%), followed by “political pressure on local authorities to address the needs of internally displaced Syrians” (44%), and an almost even split between “support with jobs and livelihoods/employment opportunities” (41%) and “more funding for projects focused on the integration of internally displaced Syrians with host communities” (40%).

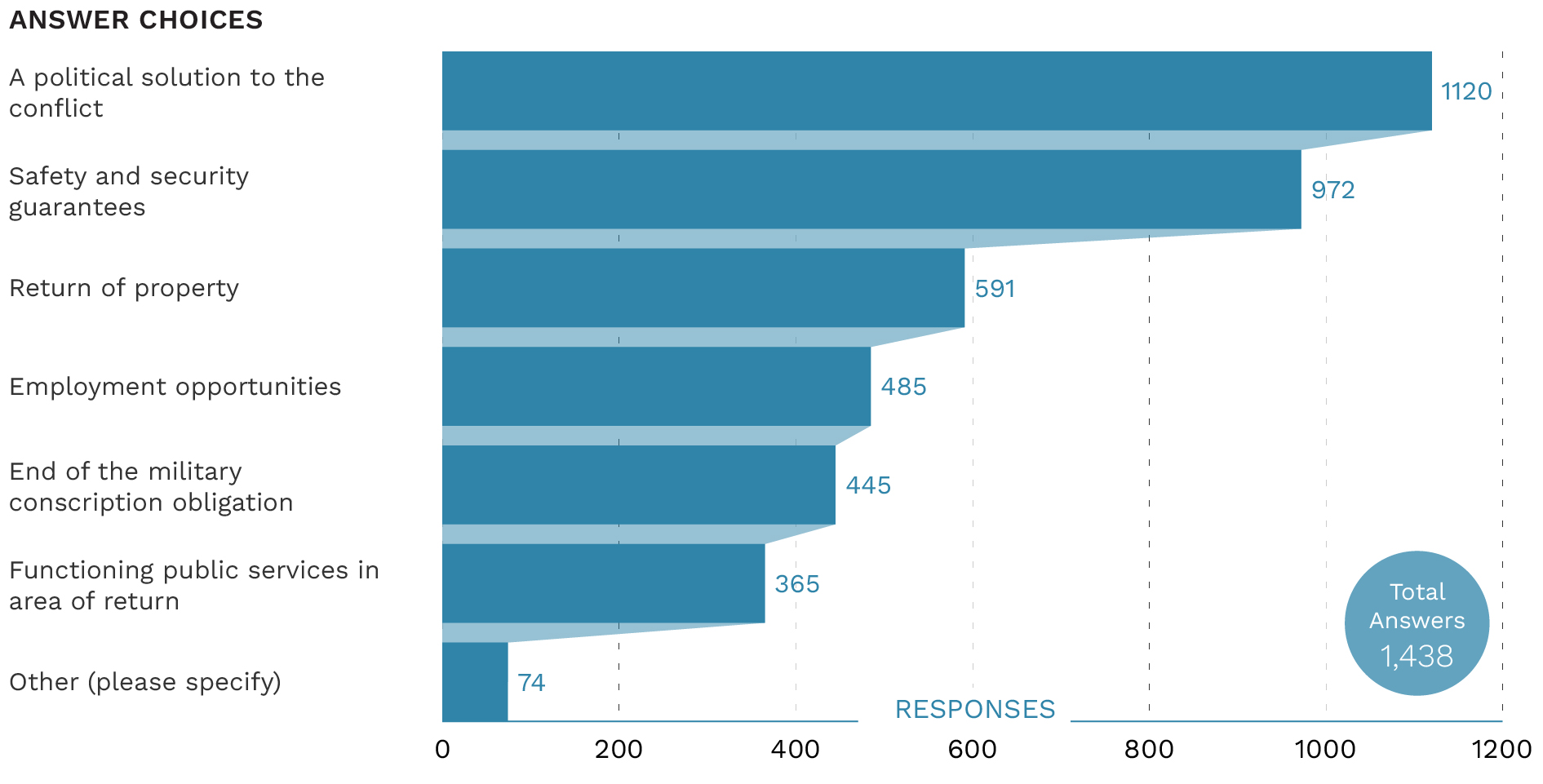

Figure 38: In your opinion, what would be needed to facilitate the safe, dignified, and voluntary return of internally displaced Syrians to their communities of origin?

Similar to the responses in the previous section, an overwhelming majority of respondents selected “a political solution to the conflict” (78%) as something needed to facilitate the safe, dignified, and voluntary return of internally displaced Syrians to their communities of origin, followed by “safety and security guarantees” (68%). “Return of property” was the third most selected option (41%), followed by “employment opportunities” (34%) and the “end of the military conscription obligation” (41%). As with the same question asked about refugees, there were no significant differences in the responses of different respondent categories.

[1] Note that “Other” includes responses from Egypt (2) and Iraq (18).

[2] Note that Figure 15 omits the 118 respondents (10%) who said “I don’t know.”

[3] Note that totals exclude “I don’t know” (117) and “I do not live/work in an area affected by the earthquakes” (331).