Executive Summary

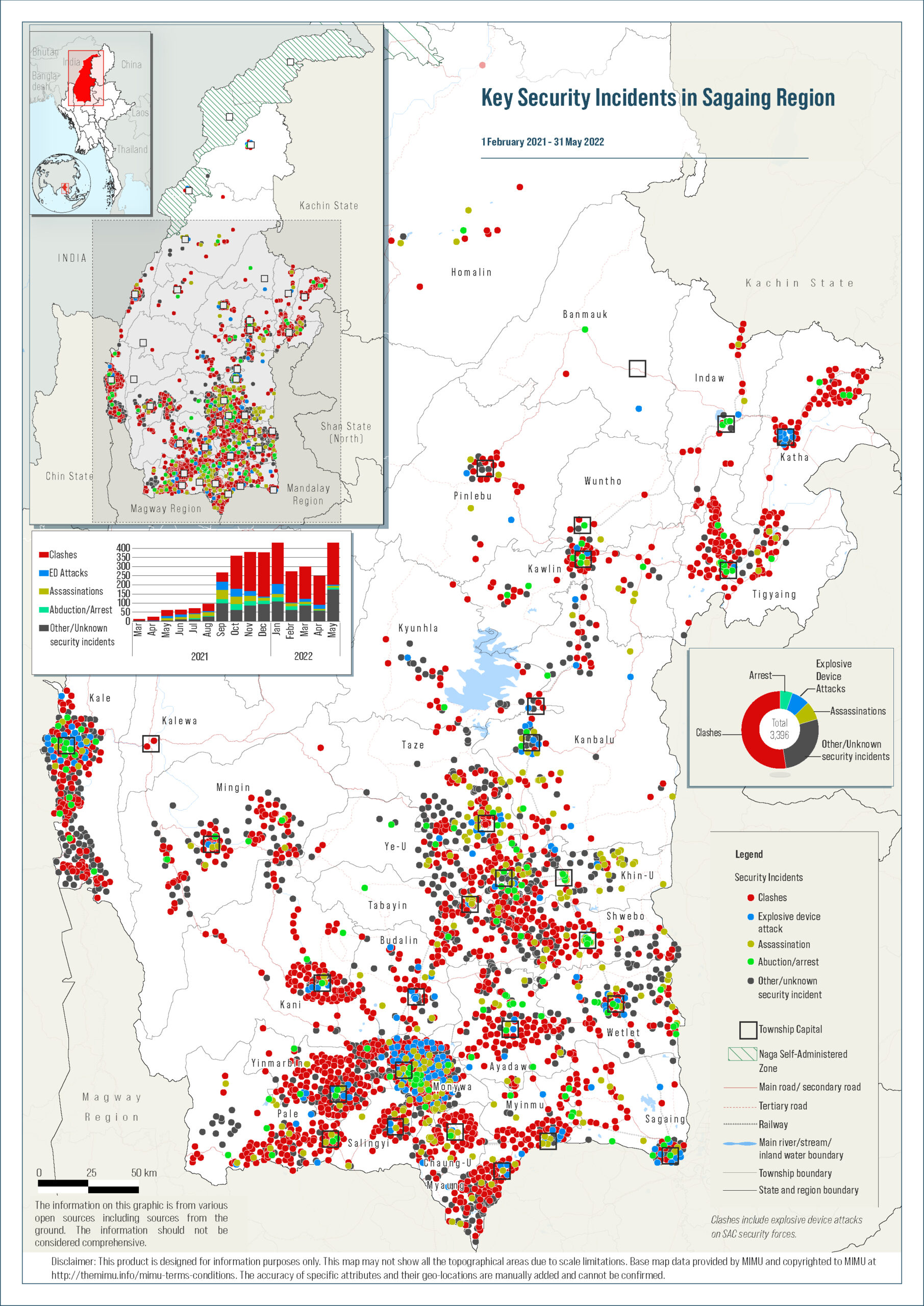

Prior to the February 2021 military coup, the ‘heartland’ regions of Sagaing, Magway, and Mandalay were among the more peaceful areas of Myanmar, with little organised armed violence to speak of. However, since the February 2021 coup, these regions have become the site of some of the most active anti-coup resistance activity in the country. Nonviolent resistance to the coup in these areas—met with military violence, arrests, and lethal force—has, over time, transformed into guerrilla-style attacks on military personnel and assets. The military has largely responded to such attacks by destroying entire villages it suspects of harbouring resistance fighters. Sagaing and Magway regions, in particular, now host some of the most intense armed conflict in the country, between State Administration Council (SAC) forces and a growing array of local People’s Defence Forces (PDFs).

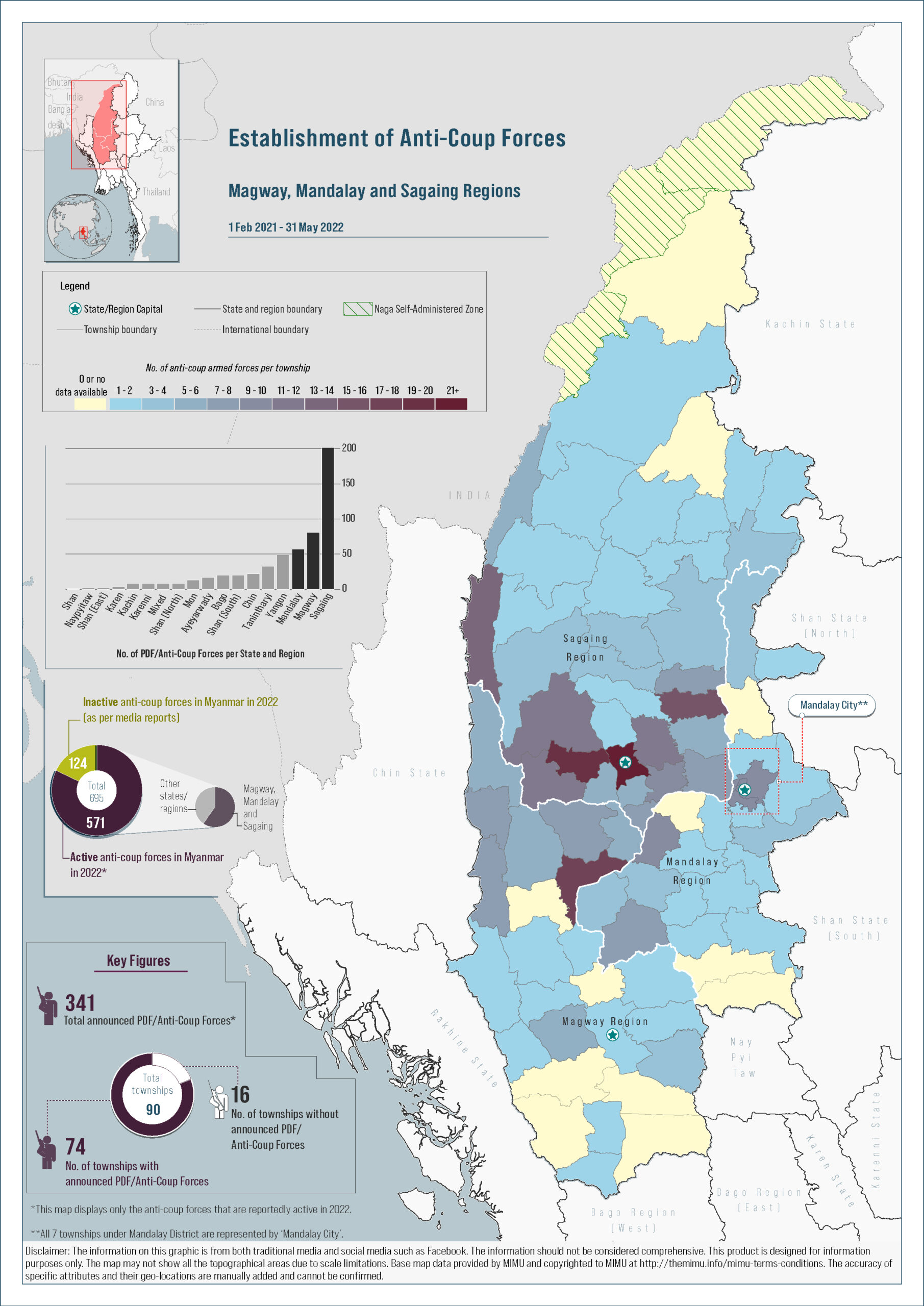

In theory, PDFs were formed as the armed wing of the National Unity Government (NUG) in its political struggle to wrest power back from the Myanmar military. Most PDFs openly state their allegiance to the NUG, and overtly pursue stated NUG objectives, such as destroying the economic interests of the military. However, the creation of many PDFs has been an ad hoc process and, in reality, only some have a direct connection to the NUG. Many continue to benefit from the training, weapons, and experience of established armed actors, and numerous PDFs have fought alongside and underneath ethnic armed organisations (EAOs)—particularly the Kachin Independence Organisation/Army (KIO/A) in Sagaing Region—raising questions about the relationship among these groups and implications for the future.

In parts of Sagaing and Magway Regions where PDFs have largely ousted Myanmar military personnel and SAC administrations, they have begun to form or support the formation of local governance bodies. However, many questions remain, including around their funding, their chain of command and allegiances, and the degree to which they actually control the areas they claim. The governance and administrative bodies built alongside emerging PDFs have also developed strategies to support service delivery for communities and assistance to those affected by conflict and crises. Known as People’s Administration Organisations (PAOs), these could in time become points of service delivery for aid actors, especially as physical access remains largely unattainable for international responders. Moreover, the organic and locally driven formation of these groups may set the template for a future Myanmar, or at least its central regions. That said, the dividing line between military and civilian authority in these regions remains extremely challenging to discern and can change from village to village. Understanding these newly forming stakeholders at a granular level will be challenging; however, it will also be critical to mounting a sustainable aid response in the heartland.

Key Recommendations

- Design and deploy new, effective response strategies to address needs arising from intensifying armed violence. Conflict escalation over the medium to long term will continue to trigger serious, lasting impacts on communities throughout the heartland, and international responders should act now to devise and implement plans to channel assistance where it is needed and where it will be needed in the future.

- Develop remote programming modalities through local responders and religious networks to provide crucial protection activities to vulnerable communities. Areas of emphasis should include resiliency support, emergency preparedness, and training on international humanitarian and human rights law, with a particular focus on the rights of those most vulnerable—including children, persons with disabilities, and women.

- Consider coordination with newly emerging local governance actors, such as PAOs. With the collapse of the SAC’s governance mechanisms, PAOs have taken on an important role in local responses and appear poised to grow in importance throughout the region. Open and frank dialogue with the NUG could help to identify potential avenues of collaboration with respect to assistance delivery throughout the heartland.

- Prioritise creative partnerships with existing local networks. There is a substantial, homegrown, and localised response network already in operation, consisting for the most part of informal groups and religious networks.

- Foreground contextual knowledge, underpinned by strong understandings of developing local dynamics and stakeholders, to strengthen the response. With multiple armed and governance actors present at the township level, due diligence, conflict sensitivity, and response effectiveness will rely on monitoring of the shifting context.

- Offer specific support for those most affected by the extreme violence ongoing across the heartland region, especially women. Women’s active participation in resistance, along with their general position of vulnerability and the impact of violence against women on the broader community, have likely driven an increased targeting of women for a range of abuses. The violence and volatility of the current context have had an enormous impact on wellbeing, while psychosocial and mental health support remains extremely limited.

Background

The opposition movement to the Myanmar military’s 1 February 2021 coup, first characterised by peaceful protests, has now transformed into armed resistance. In the face of oppressive violence, frequent killings, and mass arrests, individuals resisting the coup have taken up arms to protect their communities. Peaceful resistance has also continued, in the form of protests, boycotts, and strikes. Civil servants across Myanmar left their government positions en masse to join the civil disobedience movement (CDM) soon after the coup, and most remain on strike.[1] Desertions and defections have also reflected the unpopularity of the coup, even among the SAC’s own ranks, although precise numbers are difficult to determine: while the NUG claims more than 8,000 soldiers or police have defected since the coup,[2] has tracked 3,166 deserters or defectors as of 26 July 2022. The fear of a return to military rule is widespread and difficult to quantify, but was captured by this man in Sagaing Region:

The Myanmar military forcibly staged the coup and committed horrible crimes, destroying civilians’ lives. In addition, it destroyed the standard of democracy and civilians’ rights. We are now facing the darkest phase of the era. We have lost livelihoods and chances to seek education. … We already had over six decades of horrible experiences under dictatorship and military rule. There is no way we can accept this horrible experience again. We have to fight against the coup and the military junta, whatever it takes.[3]

Armed resistance to the military and its SAC in the Myanmar heartland—the regions of Magway, Sagaing, and Mandalay—began with a series of bombings and assassinations against people and institutions associated with the military, including its administrative structures. The SAC responded with arrests, raids, arson, and mass killings. While the disproportionate brutality seemed calculated to dissuade any further resistance, it has had the opposite effect, solidifying broad opposition against the SAC and entrenching support for local resistance. Shortly after the NUG announced the formation of the People’s Defence Forces (PDFs) as its armed wing, in May 2021, local PDFs appeared in the heartland, operating in cooperation with each other and sometimes with EAOs. PDFs rapidly grew in sophistication, particularly those with training and weapons provided by EAOs in adjacent areas.

Fighting has escalated rapidly since. In October 2021, the SAC targeted Sagaing Region and neighbouring areas in a set of offensives. Since then, the heartland has seen some of the most intense, sustained fighting in Myanmar. In March 2022, the SAC extended mobile data network blackouts to 33 townships in Sagaing Region, four townships in Magway Region and two townships in Mandalay Region—though internet connectivity has now been restored to all of Mandalay. Internet blackouts are a tactic widely used by the Myanmar military to suppress information flows to, from, and within areas in which it is perpetrating particularly severe abuse.

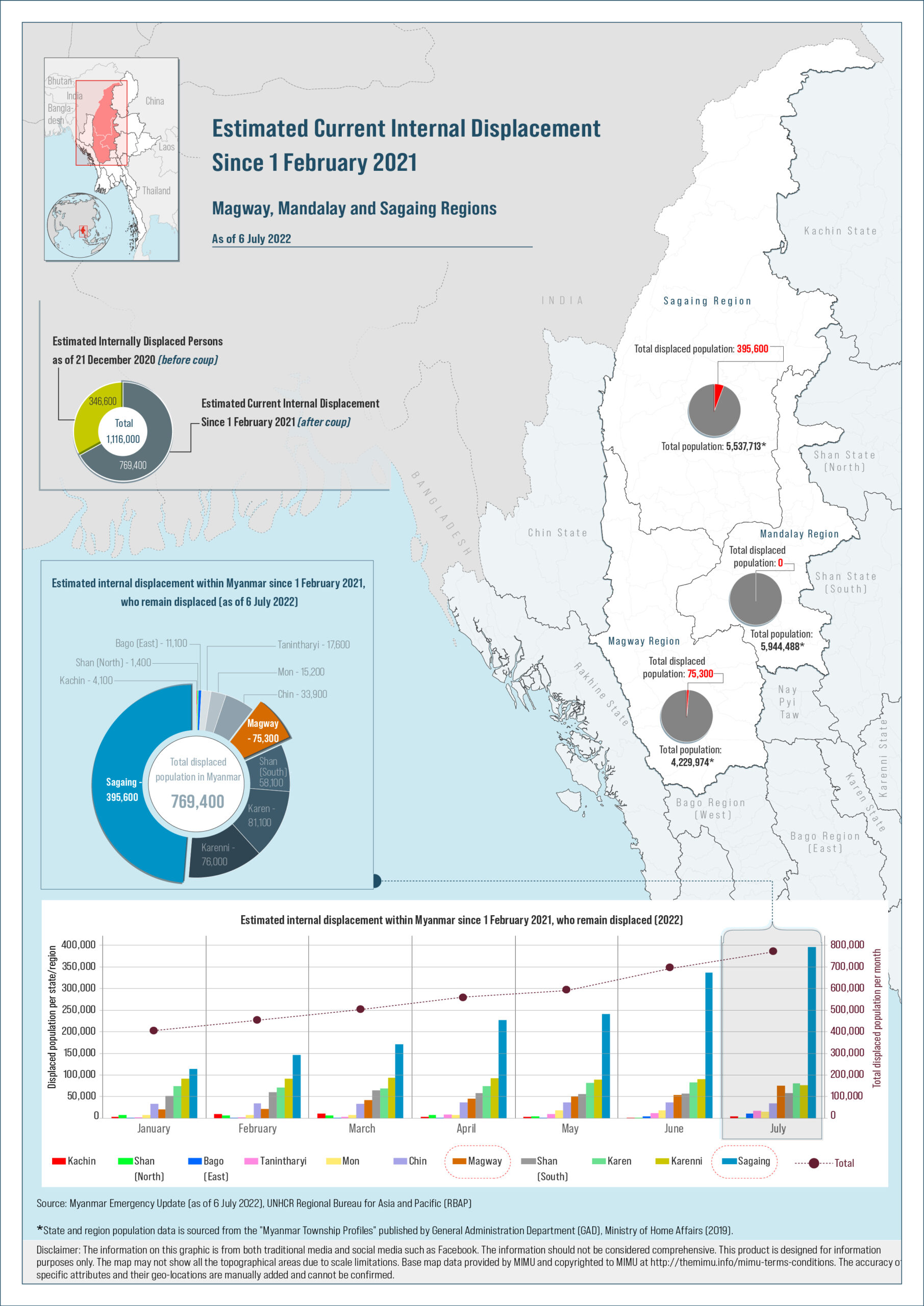

By early June, the total number of people remaining displaced inside Sagaing Region had risen to 395,600—the highest number for any state or region nationwide, accounting for nearly half of all post-coup displacement across Myanmar.[4] In Magway Region, 75,300 people remained displaced.[5] These numbers are not inclusive of the estimated tens of thousands who have been temporarily displaced, some repeatedly. There are few signs that the fighting will subside in the short or medium term.

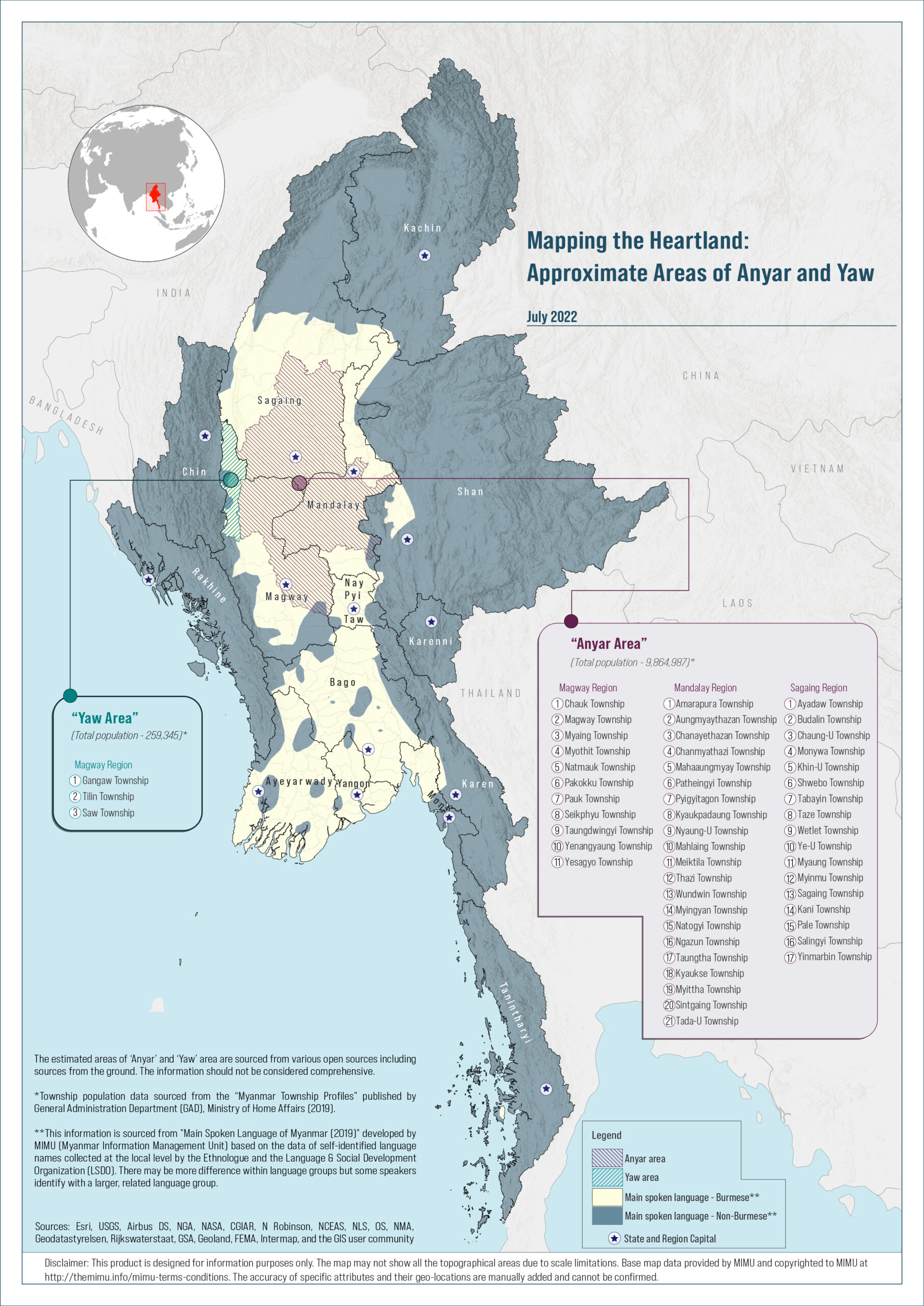

Mapping the Heartland

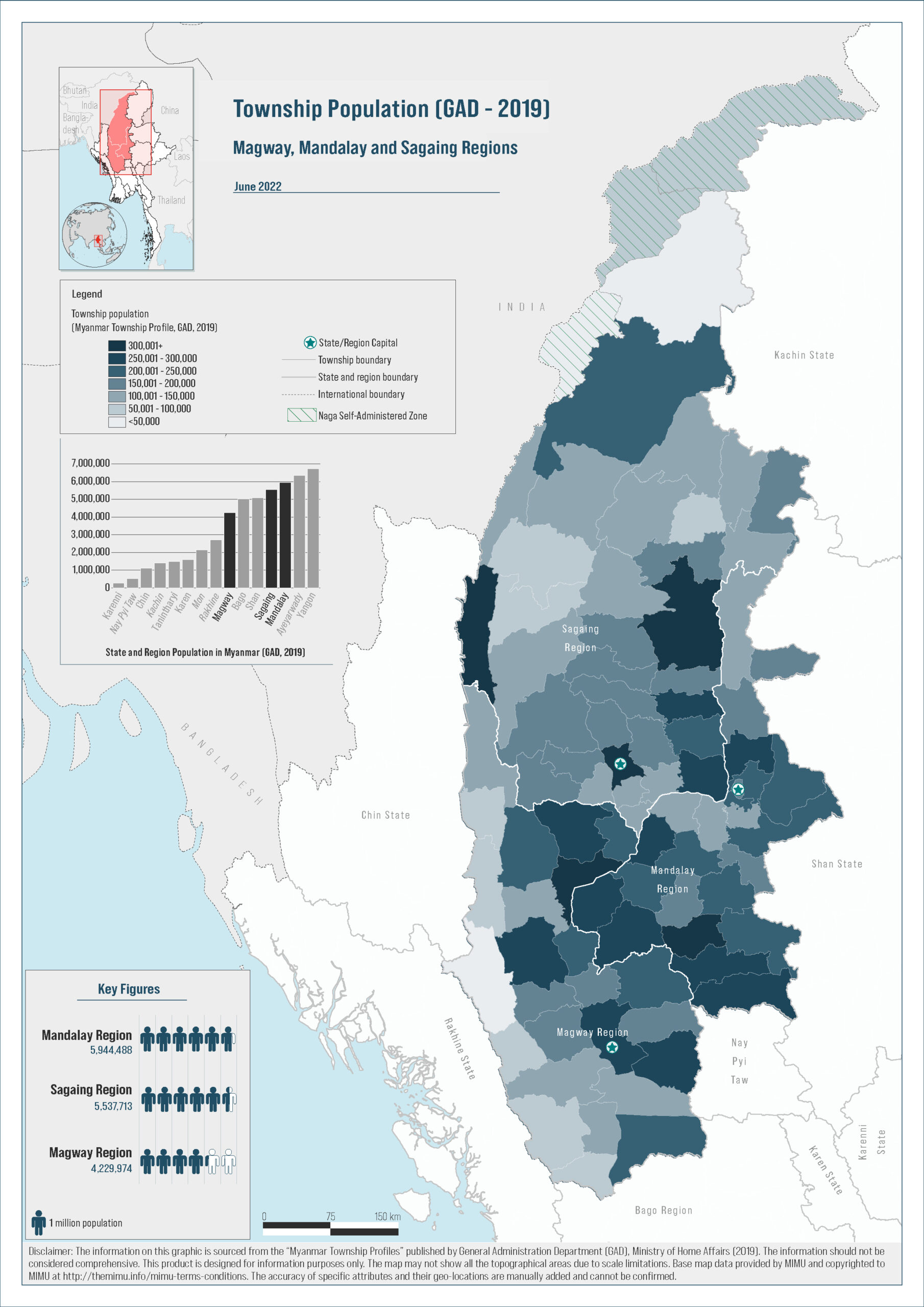

The focus of this paper is on the Myanmar heartland. Comprising the majority Bamar and Buddhist Sagaing, Magway, and Mandalay regions, this area holds a central space in the Myanmar military’s creation myth, which looks to ancient Burmese royalty for inspiration and alleged heritage. The military has touted the hegemony of the Bamar language and cultural practices as central to the notion of Myanmar identity, and has traced Myanmar’s national identity to historical origins among ancient and more recent settlements in the heartland. It has thereby prioritised recruitment from Bamar-majority areas, to include the heartland, and people from the heartland occupy prominent positions throughout its hierarchy.

More recently, control of the heartland has also been strategically important for the Myanmar military, due to the access it affords to peripheral ethnic states. The vast majority of Myanmar’s longstanding internal conflicts have been fought in the country’s hilly borderlands, mostly against EAOs; the heartland has provided the Myanmar military with critical routes by which to reinforce troops and supplies during these decades-long conflicts.[6] The Ayeyarwady River, national highways, and smaller road networks connect heartland towns and villages to those in neighbouring states. Capitalising on these advantages, the Myanmar military has situated extensive facilities and garrisons within the heartland and on its immediate border. These facilities include the military’s main air force facility in Meiktila, Mandalay Region; its Defence Services Academy in Pyin Oo Lwin (formerly Maymyo), Mandalay Region; and several light infantry divisions and ordnance factories positioned throughout.[7]

Further illustrating the heartland’s economic importance, Mandalay city—the nation’s second largest, with a population of more than one million—has long served as a major financial hub, particularly with respect to the facilitation and financing of both licit and illicit cross-border trade with China. The heartland regions also carry tremendous political weight; despite the Myanmar military’s historic ties to the region, it formed a large part of the ethnic Bamar voter base loyal to the Aung San Suu Kyi-led National League for Democracy (NLD), which in the 2020 election won all but one seat in both houses of parliament at the union level across Magway, Sagaing, and Mandalay regions.[8]

Informing widespread NLD-support, and subsequent popular resistance to the military coup, the heartland experienced an unprecedented period of economic growth and opportunity following the 2011 political opening and, in particular, the 2015 election. The national government rewarded political loyalty and invested heavily in infrastructure, improving roads, bridges, healthcare facilities, and recreational and green spaces. Monywa city, the capital of Sagaing Region, was billed as among the most developed cities in the country by major media outlets. Largely removed from the wars and atrocities ongoing in the country’s borderlands, the heartland was a major benefactor of the political changes between 2011 and 2021, however limited those changes were and despite controversies that emerged during this period.[9]

Despite these regions’ continued broad support for the central and Bamar-led democracy movement, the Myanmar military has in all likelihood been surprised by the level of resistance witnessed in this area since the coup. The military has long considered the Bamar Buddhist heartland to be its key support base, and it is now facing an insurrection there. Fighting in the heartland presents new challenges for the military, not least one of morale for those soldiers ordered to attack civilians in their home villages.

The Launch of Heartland Opposition

Following the SAC’s brutal nationwide crackdowns against peaceful protests from late February to April 2021, a wave of individuals fled the Myanmar heartland and travelled to areas under EAO control. Identifying either as private citizens or as CDM participants, most sought shelter in what they perceived to be friendly and protected EAO areas; others sought to receive military training. In particular, when the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH) issued a statement calling on citizens to “practice self-defence” against the Myanmar military, on 14 March 2021,[10] many youths travelled to EAO-controlled areas and undertook basic combat training, including explosives training.[11]

Meanwhile, residents who stayed in the heartland began to form neighbourhood watch groups operating at the township, ward, or village level,[12] providing protection for protesters, CDM staff, and other civilians against SAC violence. Over time, these watch groups evolved into more organised armed resistance entities. As importation, production, and use of improvised firearms increased, these armed entities engaged in more violent opposition to the SAC.[13]Many of these regions had been key conduits for the trade of arms into western Myanmar during the 2018–20 armed conflict between the Myanmar military and the United League of Arakan/Arakan Army (ULA/AA), and as such were easily transformed into arms markets.

Defining PDFs

In May 2021, as various community-based resistance fighters secretly returned to the Bamar heartland after completing basic military training in EAO areas, the NUG officially announced the formation of the People’s Defence Forces, or PDFs.[14] Despite its public statement, the NUG did not immediately appear to increase its engagement in the armed violence escalating throughout Myanmar.

Although the term ‘PDF’ is now often loosely applied to many anti-coup opposition forces, regardless of their actual posture with respect to the NUG, the NUG itself officially distinguishes between forces it considers to be PDFs and other armed entities. Essentially, to be officially recognised as a PDF by the NUG, an organisation must pledge allegiance to the NUG and agree to abide by the NUG code of conduct.[15] Outside of this official designation, however, ‘PDF’ has become shorthand for any armed group involved in resistance to the 2021 coup—particularly those consisting of a majority of ethnic Burmese members, but including some groups consisting mostly of ethnic minorities operating in the country’s borderlands. The colloquial usage of the term belies the diversity among these groups and the fact that many anti-coup armed groups do not subscribe to the PDF label. There remains a diversity of approaches to strategy, allegiance, and long-term vision. All are broadly united in opposition to the military coup, however, thereby making cooperation possible.

Connections to the NUG

As armed violence intensified but NUG involvement with it did not, it appeared the NUG had little if any direct command and control over the PDFs in practice. As the COVID-19 crisis was subsiding, the NUG publicly declared 7 September 2021 to be the “D-Day” of the “people’s defensive war” against the SAC.[16] The announcement was followed by a spike in incidents of armed violence involving PDFs throughout the heartland.

The NUG’s Ministry of Defence (MOD) is the first such ministry to exist under Myanmar civilian leadership since the 1962 coup. The MOD has direct control over only a small proportion of anti-coup armed groups currently active. As a result of circumstance, the NUG’s defence posture relies on an ecosystem of PDFs and relationships with EAOs predicated on opposition to the military and promises of cooperation towards a federal union. This is reflected in the overall structure of the MOD, which is designed to take direction from the NUG prime minister while maintaining relations with EAOs in a Federal Alliance through a Defence Coordination Council.[17]

Although the MOD purports to oversee PDF operations, there is little evidence that it exercises direct command and control over any great proportion of armed actors—and most PDFs operate with near complete autonomy from any central NUG command structure. The organisational structure of the MOD contains a range of internal departments,[18] with a separate organisational structure under which PDFs supposedly operate. These structures reflect a heavy emphasis on support functions but demonstrate little focus on tactical command and control functions.

Command, Control, and Structural Relationships

Like all PDFs across Myanmar, those active in the heartland are not monolithic. Rather, they are highly diverse groups with identities born of the different communities within which they originate and operate. With evidence pointing to the growing sophistication of heartland PDF tactics and weaponry, it appears likely that EAOs in the borderlands around the heartland are supporting certain Sagaing, Mandalay, and Magway region PDFs—particularly those that appear better equipped and better trained.[19] To maintain the supplies necessary to sustain their personnel and activities over time, many PDFs will likely need to maintain strong operational links to benefactors—presumably EAOs—to remain operational. Within this diverse PDF landscape, it is probable that certain EAOs maintain closer relations with particular PDFs and not others, based on the EAOs’ objectives and interests. Some may cultivate particular PDF relationships in order to use strategically placed PDFs as proxy forces when the need arises or to create a buffer around their areas of control.

The apparent operational doctrine employed by heartland PDFs further suggests close KIO/A involvement in PDF activities throughout these regions. In particular, the trend of targeted killings of local officials followed by a campaign of attrition centred on ambush tactics parallels the largely successful approach previously adopted by the ULA/AA in western Myanmar. Given the close relationships between the ULA/AA and the KIO/A,[20] lessons learned in one conflict zone are easily shared. More recently, however, sources report that the relationship between the NUG and KIO/A has been affected by the controversies regarding the NLD’s participation in the National Unity Consultative Council—a coalition of elected MPs, EAOs and other groups opposing the military. The July 2022 withdrawal of the Kachin Political Interim Coordination Team (KPICT) signals a pivot by Kachin stakeholders, including the KIO/A, away from multilateral engagement facilitated by the NUCC and toward bilateral engagement with the NUG and CRPH. However, even with the relationship between the NUG and KIO/A evolving, and possibly under strain, it is not only the KIO/A providing support to PDFs operating in the heartland. Other EAOs have also been crucial to training, logistics, and ground operations.

There has been a gradual trend over the past year of the NUG gaining greater control over PDFs across Myanmar. NUG contributions to PDFs in the heartland include the provision of some degree of political legitimacy; provision of policy-level guidance; public articulation of shared aspirations for the restoration of a civilian government and pursuit of genuine federalism in Myanmar; and some arms distribution. The NUG also occasionally directs funds and resources from the diaspora and domestic donors to individual PDFs for the purchase of weapons and materiel, in addition to its delivery of funds to support the livelihoods of CDM members. The NUG’s tax plan envisions 40 per cent of revenue flowing to PDFs.[21] However, even if the NUG is making direct financial contributions to PDFs, it does not appear capable of exercising command and control over them. In this vacuum, it is probable that benefactor EAOs have taken on essential command and control functions for PDFs operating in or near their areas, while still affording PDFs some level of autonomy. As a NUG source reported, “PDFs are akin to the People’s Militias of previous eras and are not within the direct control of the NUG.”[22]

The reliance on support provided by EAOs, each with its own priorities, may create tension in the relationship between PDFs and the NUG. Despite some efforts towards ethnic inclusion, the NUG still remains dominated by the NLD, with which many EAOs have had fraught relationships in recent years. Several EAOs cite disagreements on the peace process and the previous NLD government’s demonstration of hesitancy on constitutional reform toward federalism as sources of mistrust.[23]

Illustrating the complexities in PDF organisation, allegiances, and coordination, respondents report two particular varieties of PDFs present in many townships in the heartland. The first kind are those purported to be under the command of the NUG’s MOD. These groups are nominally responsible to PAOs at the township level, and are known locally as Pa Ka Pha—the Myanmar-language acronym for ‘PDF’. These groups are typically closer to NLD personnel, the NUG, and PAOs. The second kind of PDF are locally organised groups not under any effective NUG command, but referred to locally as PDFs. While they may claim some allegiance to the NUG, this kind of anti-coup armed group is not under the direct command of the NUG’s MOD in terms of day-to-day operations.

In some townships, both types of PDFs are active and have generally coordinated with a reasonable level of effectiveness to date. Some sources report rising tensions between the leaderships of these two PDF types in certain townships, and PDF forces have reportedly even detained Pa Ka Pha leaders in some areas.[24] Elsewhere, tensions appear to be growing between the Pa Ka Pha and other anti-coup armed groups, referred to as guerilla forces to differentiate them from PDFs. Community sources also report growing concerns about the power competition between these multiple actors, as competition for scarce resources, including arms, becomes more and more important for the sustainability of all armed groups in the heartland.

Inter-PDF Tensions

While the vast majority of anti-coup forces, including PDFs, appear to operate with a significant level of coordination with each other, the multitude of armed groups and lack of formal ties have sometimes given rise to power competition and division—occasionally resulting in violence. This has triggered a series of challenges for communities, the NUG, and PDFs themselves.

The most serious allegations have been levelled against the Yinmarbin PDF, in Yinmarbin Township, Sagaing Region. On 19 March 2022, the leader of this PDF admitted that members of his group had killed 10 members of other PDFs in Yinmarbin Township.[25] He agreed to cooperate with an NUG investigation into the killings, but said he did not order the executions himself. The killings were first reported in November 2021, and the NUG launched an investigation in December. The Yinmarbin PDF also faces other accusations, including that it has killed at least 21 area residents.[26] Other anti-coup armed actors have also been accused of using the title of PDF for personal gain, or taking part in abuses against civilians. In May 2022, five members of an anti-coup force in Myingyan Township, Mandalay Region,[27] were detained by the Chaung-U PDF, in Sagaing Region, on the basis that they had committed abuses against civilians. The NUG has ordered the Chaung-U PDF to keep the fighters in custody, in decent conditions.[28]

The Yinmarbin PDF’s alleged misconduct may have prompted the NUG’s 14 March formation of a new commission for investigating war crimes. The commission briefed the acting president and prime minister on the Yinmarbin PDF situation, conducted a remote investigation based on interviews with the accused persons and family members of the victims, and came to a conclusion on 21 March. On 26 March, the MOD released the initial findings of its investigation into the Yinmarbin PDF, and confirmed that members of this PDF had killed at least 10 people, either mistakenly or due to inter-PDF tensions. The investigation was complicated by internet and communication difficulties, and by the fact that the Yinmarbin PDF had not officially joined the NUG’s command structure at the time of the alleged crime.[29]

Challenges such as this are to be expected within the NUG command structure, as the NUG is relatively inexperienced at such investigations and is navigating political risk at the same time as it develops policy and procedures. The delay in its investigation likely raised tensions among resistance groups in Sagaing Region and between PDFs and communities, especially given the lack of transparency around the investigation, findings, and consequences.

A nominal loyalty to the NUG has proven to be no guarantee of unity and coordination among PDFs. Indeed, power struggles and competition among PDFs are likely to continue to be a serious issue in Myanmar’s complex landscape of armed conflict and are expected to remain a challenge throughout potential future political negotiations. Internal armed conflicts in Myanmar, and elsewhere in the world, have proven the propensity for the fragmentation of armed groups, infighting, and competition for leadership and individual gain. Although several anti-coup armed groups have been accused of misconduct and are currently under investigation by the NUG, it should be remembered that the vast majority of abuses against civilians are carried out by SAC forces.

Presence, Activity, Impact

As of 10 June, this analytical unit identified 341 distinct PDFs operating in Sagaing, Magway, and Mandalay regions, 75 of which are present across more than one township; exact personnel numbers are not known, but the PDFs’ combined force strength is considered likely to be several thousand. (Additionally, other, lower-profile anti-coup forces are also certainly operating in these regions.) Incidents of armed violence involving PDFs have steadily increased in number and frequency throughout the post-coup period, although the third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic across Myanmar briefly slowed this trend in June and July 2021.

From 1 February 2021 to 31 May 2022, 4,818 security incidents involving anti-coup forces were identified across Myanmar. The highest number were in Sagaing Region, where 1,884 incidents took place, while Magway and Mandalay regions had the second and fourth highest number of incidents respectively.[30] It is striking that the frequency of incidents in the heartland is significantly more than in traditional borderland areas, where long-standing and well-equipped forces such as the KNLA and KIA continue to engage in armed conflict with the SAC. The armed activity and engagement of heartland PDFs has increased over time—despite the Myanmar military’s known capacity and tendency to perpetrate retaliatory acts of extreme violence,[31] including against communities where it believes PDF members are located[32]—suggesting conflict across the three regions will be neither short lived nor one sided.[33]

In addition to these PDFs, several other anti-coup armed groups operate with almost no active relationship to the NUG or to EAOs. These groups are largely active in urban areas and are sometimes referred to as underground, or ‘UG’, guerrilla groups. While their members may have travelled to EAO-held or other border areas for training, they operate only in coordination with other anti-coup armed groups in their areas. They are united with other resistance groups in opposition to the coup and a desire for political change, although the immediacy of the resistance has often overshadowed the need for the formalisation of relationships and command structure.

Trajectory

As the conflict continues, PDFs are likely at least to survive, if not continue to grow. Particularly given the military’s pattern of treating entire villages like enemies—shelling, razing, and looting villages accused of harbouring PDF members—people have little reason to exercise neutrality, and many are likely to side with the resistance. Although it is possible that a few may dissolve, PDFs are likely to be a feature of the landscape for as long as Myanmar’s internal conflicts endure.

The NUG has put forward a Federal Army scenario, in which all recognised PDFs fall under its command to form a nationwide armed force. In reality, the NUG has limited control and no clear chain of command over PDFs at present. As discussed above, challenges to a centralised model are numerous, ranging from difficulties with command, enforcement of codes of conduct, and the influence of other actors, such as EAOs. It is unclear how this issue will develop, but it seems unification may be more likely if the NUG is providing financial or other support to PDFs; otherwise, the groups may be inclined to go their own way.

PDF links to EAOs are much stronger than the former’s ties to the NUG, especially due to tangible flows of support, including training and weapons. These relationships could (and likely will) take several different forms in future, depending on the particular needs and interests of EAOs. PDFs with strong connections to EAOs could be folded entirely into the command structures of the latter, ultimately operating as EAO units. Others could end up as proxy forces operating with a looser connection but in general alignment with the EAO, especially those PDFs that exist on the periphery of EAO-controlled areas and could serve as a buffer between ethnic borderlands and the central Myanmar SAC strongholds.

Finally, at least some further fragmentation is likely—as demonstrated by the multiplicity of armed actors across Myanmar. All are broadly united in an opposition to the military coup, which makes cooperation possible in the short term. However, there remains a diversity of approaches to strategy, allegiance, and long-term vision. Some PDFs will likely splinter off from the wider coup opposition movement as interests begin to diverge, with their trajectories to depend on the will and interests of their leaders.

PDFs and the People’s Administration

Though outnumbered, outgunned, and inexperienced, PDFs have gained and held significant ground in parts of the heartland, especially Sagaing Region, pushing the SAC out of most rural areas and creating space for alternative civilian governance structures to emerge. One young woman in Kawlin Township, Sagaing Region, noted that “in our township, most village administrators have resigned since last year, suspending all administrative functions at the community level”.[34] To replace SAC structures, nominally NUG-linked governance bodies have been established in many areas of the heartland. For the time being, their activities remain limited, and anti-coup armed groups and other traditional village leadership structures are just as likely to be providing services.

On 25 April, the NUG Ministry of Home Affairs and Immigration claimed publicly that it had established PAOs in 29 townships in Sagaing Region and seven townships in Magway Region.[35] Such organisations have also emerged in other parts of the heartland and elsewhere in Myanmar, almost always at the township level. PAOs are nominally NUG-linked. They exist across a broad spectrum of operational capacity, activity, and community acceptance. Their activities remain limited and they should be thought of as service providers, rather than as formalised governance actors. Their most common activities involve providing or facilitating material support for IDPs, collecting demographic information, and coordinating some healthcare, education, and justice services.

The People’s Administration Organisation in our area [Monywa Township] is doing some activities such as collecting information from the village leaders, delivering food and shelter to displaced people, and establishing an early warning system for local people. However, their work is very limited.[36]

Over the past year, SAC forces have attacked areas where PDFs and PAOs have made public claims about their activities. PAOs have primarily emerged in areas where a strong PDF is already present and capable of protecting the township in which it is developing its administration or governance mechanisms, leading to often close relationships between the two and some overlapping functions. In many areas, PDFs are also providing some level of service delivery for communities. Typically, they are supplying or facilitating material assistance for IDPs and providing local law enforcement, justice, and early warning systems for civilian evacuation ahead of armed clashes and SAC offensives. One respondent noted that, in her area, there are many phone thieves, and that PDF members help to catch them, providing justice for the victims of various crimes.[37] In some areas, they are also mitigating deforestation by preventing the activities of illegal loggers.[38]

Although a Township People’s Administration Organisation was established in Wetlet Township in May 2021, its leaders are not very strong in leadership and management, delaying the establishment of administrative functions and public services on the ground. PDFs mainly control the villages and they are responsible for the security and maintenance of law and order within the area. Due to their efforts, only a small number of criminal incidents, such as thefts, broke out last year. For thefts, they traced the thieves and punished them very seriously.[39]

Community perceptions of PAOs are complex. Communities report that they are now looking to PDFs, more than PAOs, for leadership. PDFs are more visible and have earned a substantial following for their willingness to put themselves in the path of the SAC’s brutality. In contrast, PAOs are often far less visible, raising questions about their commitment to the revolution, their ultimate objectives, and their individual interests.[40] For the time being, there have been few complaints against PDFs and their activities in law and order. However, the urgency of the situation and the otherwise dearth of protection mechanisms likely means that communities are willing to rely on what is available. At the moment, PDFs appear to be their best option. However, given trends elsewhere in Myanmar, it is likely that prolonged conflict and exposure to particular armed or governance actors will precipitate a growing number of complaints against PDFs.

Grinding Resiliences: SAC Tactics in the Heartland

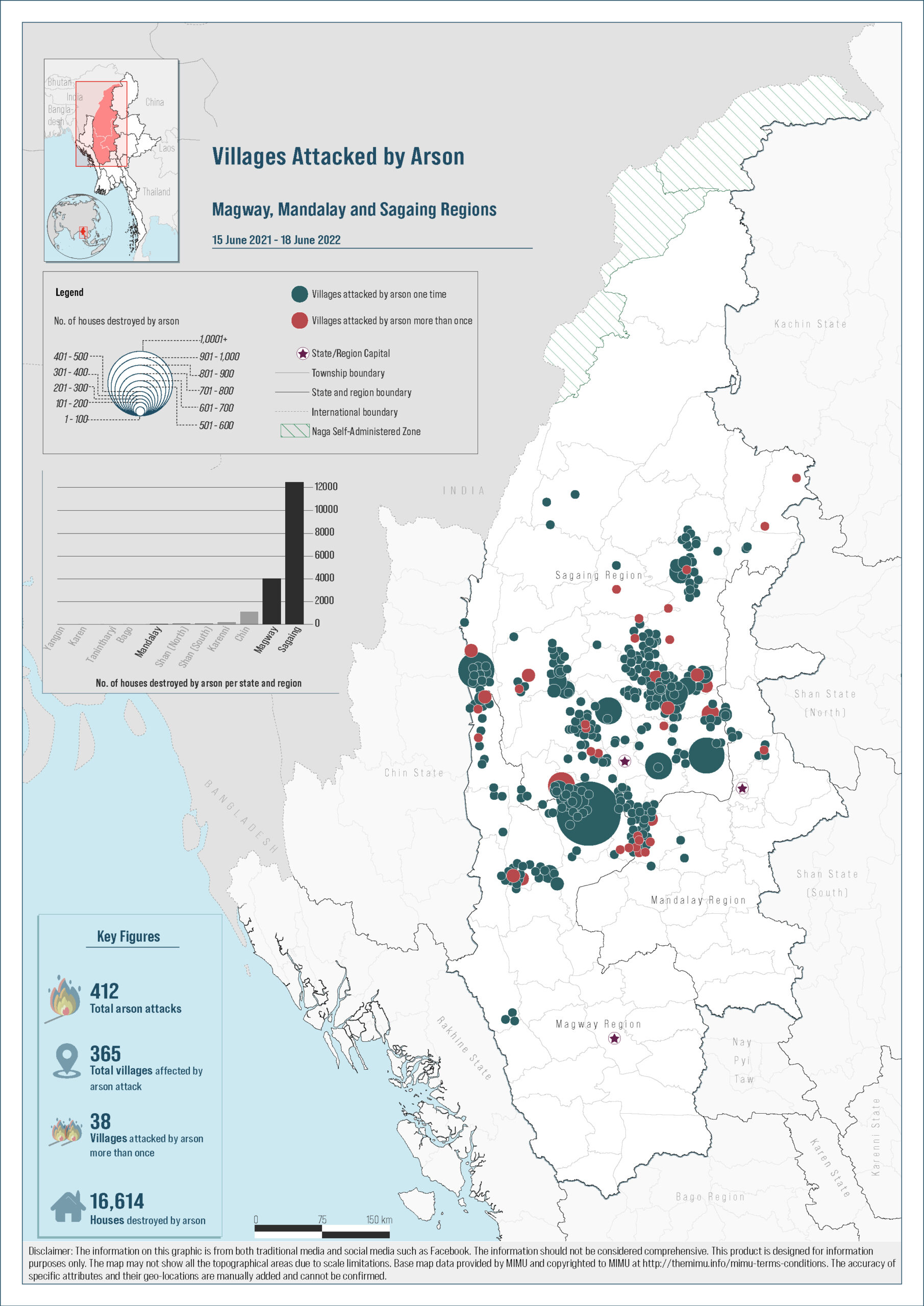

The Myanmar military has perpetrated brutal violence against civilians in its attempts to reclaim control over the heartland. As in the SAC’s campaign against EAOs and the borderland communities it perceives to be supporting them in recent decades, the razing of villages has been a cornerstone of its violence in the heartland. 18,938 houses destroyed by arson were recorded since the coup; responsibility for the vast majority of these fires lies with the SAC or actors aligned to it.[41] Moreover, there is a clear recent trend of intensification, with over half of these houses—9,673—burned down in May–June 2022.[42]

Abuses committed against civilians by the SAC include detention, torture, sexual violence, the use of human shields, and extrajudicial killings.[43] The SAC’s internet blackout and attacks on the media and civil society make it extremely difficult to gauge the extent of its abuses, likely by design. The Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma) has been at the forefront of documenting arrests and the killing of civilians. According to its data, as of 10 June 2022, the SAC held 11,808 people in detention and had killed at least 2,131.[44] The organisation notes that the actual number of fatalities is likely much higher. Indeed, numerous massacres have been documented in Sagaing Region alone. Some of the abuses committed include:

- In a single incident in early May, SAC forces and Pyu Saw Htee militiamen reportedly massacred 20 civilians from Shwebo, Butalin, Khin-U, and Ayartaw townships, Sagaing Region. Residents said the victims included men in their 70s and at least one young woman. Members of the group—which had been hiding from the SAC in a Buddhist nunnery—had been forced to walk alongside a military convoy, likely functioning as human shields, ahead of their execution. Eyewitness reports and images obtained by Radio Free Asia indicated that some of the victims had been made to lie face down in the dirt before being shot, while at least one had been set alight.[45]

- On 18 April, SAC forces and Pyu Saw Htee members reportedly raided and set fire to the 20 remaining houses in Kin Ma village, Pauk Township, Magway Region following a 2021 attack in which SAC forces destroyed nearly 200 homes.[46] After razing these last houses on 18 April, SAC soldiers also raided the temporary displacement sites near Kin Ma and Chaung Zon villages, burning down all makeshift tents and temporary shelters. The attack came after the local PDF attacked SAC troops located near Kin Ma village the day before.

- On 5 March, following clashes with local resistance forces, SAC forces reportedly stormed Inn Nge Daunt village, Pauk Township, raping and killing a 40-year-old woman, stabbing her three-year-old daughter to death, and abducting her other daughter along with 28 other people—including 12 women and children. (Depending on the specific circumstances, sexual violence and infanticide can constitute war crimes or crimes against humanity.) On 3 March, the same SAC forces also burned down approximately 270 houses in Lel Yar and Let Pan Hla villages.[47]

- On 7 December 2021, SAC forces reportedly killed 11 unarmed people, including children, in Done Taw village, Salingyi Township, Sagaing Region. Locals who found the remains of the victims believed they had been burned alive. The killings were apparently in response to a PDF attack on an SAC convoy.[48]

The SAC has also applied another tactic from the borderland wars: the sponsorship of militias. The most notorious type of Myanmar-military aligned militia to date has been ‘Pyu Saw Htee’—a label used by national and international media and other observers to refer to a large variety of armed groups sympathetic to the SAC. International Crisis Group, which conducted a comprehensive investigation into these groups, suggests that Pyu Saw Htee is best understood as a “loosely connected set of village-level networks across the country, having widely varying characteristics and capabilities”.[49] These groups existed before they started receiving support from the Myanmar military, having been formed usually by pro-military individuals, or more recently by others concerned about attacks from anti-coup armed actors.[50]

While the Pyu Saw Htee certainly lack the broad community support that PDFs can claim, their continued presence and activity is testament to the support they receive, not only from the SAC, but from some villages. In particular, certain villages in the heartland are now notorious for their long-standing military ties, and are populated by households consisting of veterans or others with close links to the military, even if they are not especially supportive of the coup.[51] A man in Chaung-U Township, Sagaing Region, notes:

Even though 70 percent of the local area has been controlled by the PDFs, there are some villages where Pyu Saw Htee members are strong. If the military movements happen in our area, the Pyu Saw Htee members along with the soldiers and the integrated forces commit crimes like burning houses, looting valuables, and killing civilians.[52]

A woman attending university in Sagaing Region notes that there are only certain areas where Pyu Saw Htee can operate freely:

Different local PDFs such as Snake Eyes, Alpha Seven, Shwebo PDF are present in our and nearby villages and they have the most popular support. However, SAC forces and Pyu Saw Htee groups remain strong in urban areas, but don’t have strong popular support.[53]

In a 25 March press conference, the SAC indicated that it would continue its approach to Pyu Saw Htee, “implementing a defence system for the people by the people”.[54]

The most disturbing pro-military faction may be the Thwe Thauk targeted killers. More than militias, these groups are better understood as death squads; as clandestine as they are brutal, they leave the bodies of their victims in public spaces, complete with cards carrying the group’s insignia. Literally translated as ‘blood-drinkers’, ‘Thwe Thauk’ is perhaps better translated as ‘blood-brothers’. The name references both a high position in the Burmese Imperial army and long-standing traditions of comrades drinking each other’s blood to strengthen their alliance.[55]

The first Thwe Thauk group emerged in Mandalay, where it claimed responsibility for the murders of NLD members and supporters in the urban area. Groups with similar names have since launched in Yangon, Nay Pyi Taw, and elsewhere, and have claimed at least 19 victims to date. No explicit evidence of SAC-backing for these groups has emerged and both the SAC and the Mandalay Thwe Thauk have denied any relationship.[56] However, their activities fall into established patterns of military-sponsored civilian violence.[57] A former Myanmar military intelligence officer told this analytical unit that they suspect the Thwe Thauk leadership have experience in Myanmar military intelligence—either as former or current officers—as the emerging group seems too organised and efficient to be civilian led.[58]

The SAC has also sought to instrumentalise Buddhism in its fight against anti-coup resistance. For decades, military propaganda has painted the military as the protector of Buddhism and, by extension, the Myanmar identity. This rhetoric has had some, if limited, utility during its wars against ethnic and religious minorities in the borderlands, but has fallen flat during its campaigns against the heartland population, who are now witnessing firsthand the military’s brutality. Some members of Pyu Saw Htee are Buddhist nationalists who sided with military-backed political parties during the 2020 election and who were previously vocal in their support for attacks on Muslims in Myanmar.[59] These groups are now facing off with the majority Bamar population, and some respondents note that this may further weaken public support for the xenophobic anti-Muslim rhetoric that characterised the 2011–2021 period.

Women and the Resistance: “We Can All Be Warriors”

Women are among the most vulnerable demographics amid Myanmar’s armed resistance to the coup. However, this research also points to the leadership roles women are taking on in the post-coup era. Rather than presenting women as victims of SAC abuses, respondents pointed to women’s resistance to the coup. In November 2021, women in Myaung Township, Sagaing Region, formed the Myaung Women Guerrilla Group (MWGG), to empower women and protect civilians.[60] While armed groups in Myanmar have traditionally been dominated by men, respondents note that this is changing. A man who spoke to this analytical unit openly admired the courage of women joining the resistance.

Women from my family are now training and joining PDFs after their communities are attacked. … I am also active in politics but I don’t think I have that kind of courage. I’m impressed. … I used to think they would just live in the village and get married. Now my perspective has changed and I listen to women more.[61]

Outside of armed combat, the conflict has also led some women to assume new roles in their communities. In one household in Wetlet Township, Sagaing Region, for example, the men were absent for health and political reasons, leaving only the women at home. When an SAC raid forced the displacement of the village, the matriarch and daughters of the family took up new leadership roles, organising the flight of the household to a displacement site.[62] In another example, the female members of a family in Magway Region were forced to flee after the SAC arrested their male relatives for affiliation with PDFs and burned the family house to the ground.[63] New female-headed households are emerging across the heartland, changing the roles of women in communities and reconfiguring gender norms. One woman in Mandalay Region noted, “We can all be warriors”.[64]

Another respondent in Mandalay Region noted that the coup and subsequent resistance has exposed everyone in Myanmar to politics—including women who previously may have had little interest in political engagement or been excluded from political engagement.

Many women didn’t have exposure to politics previously, but they know what is at stake with the coup. They are willing to sacrifice a lot for their families, for their kids, and their future. Views of women are changing, among themselves too.[65]

As a male-dominated institution, the military appears to be especially sensitive to women’s resistance, and it often seems to explicitly target women. Such targeted violence may be due to these sensitivities, women’s implicit vulnerability to violence, the knock-on community impacts achieved through the targeting of women, or any combination thereof. Additionally, SAC forces target women for abduction and use as human shields, perhaps assuming that anti-coup forces will be reluctant to attack military columns marching alongside women from the communities insurgents hail from. This has been an established Myanmar military tactic for decades.[66]

It is not uncommon for the SAC personnel to detain other family members if the specific individuals they’re searching for are not at home. At least two March 2022 instances were recorded in the heartland in which SAC forcesreportedly abducted female family members—sisters and mothers—in lieu of the alleged PDF members they were seeking.[67] The Burmese Women’s Union reports that, since the coup, the SAC has killed 181 women, arrested 2,127, and sentenced 153.[68] Women in the SAC’s custody are at high risk of sexual violence. The Myanmar military has used systemic rape and sexual violence against women throughout its decades-long conflicts in ethnic borderlands.[69] This has continued into the post-coup period. Depending on the circumstances, such sexual violence can constitute war crimes and crimes against humanity.[70]

Emergency Response to a Broken Heartland

The international humanitarian response to mass displacement and suffering in the heartland has been limited. This is a result, first and foremost, of SAC obstruction to the provision of assistance. In addition, the heartland experienced limited displacement and had few humanitarian needs before the coup. As a result, it was not a traditional response area for agencies. Relationships with communities and local civil society are limited, making navigation of the context difficult. Although the geography of the Myanmar heartland precludes the accessibility afforded to areas within easy reach of cross-border INGO activities from Thailand, these channels are nonetheless serving to deliver some urgently needed aid to the heartland now—although the process may be slow and expensive relative to the areas historically linked to these channels.

Meanwhile, despite PAOs emerging throughout the heartland, the NUG’s capacity for assistance remains hamstrung by a lack of coordination with key stakeholders, ranging from EAOs to international agencies. Despite these challenges, the NUG has made considerable gains with respect to its mobilisation of the Myanmar diaspora for both political and financial support. For the most part, however, heartland communities suffering from the impacts of armed conflict have relied on local and national support networks. Some former staff of international humanitarian agencies have also played roles. These systems have allowed communities in the heartland to maintain a significant level of resilience.

Community support networks have played crucial roles in the localised response. The lowlands of the Myanmar heartland have thriving social support networks, underpinned by high levels of social capital established during decades of government neglect. The years of economic development ahead of the coup have bolstered the resources underpinning these networks, and individuals and households are digging into cash and gold reserves to support those in need.[71] While some resiliency remains, the longer the violence drags on, the more difficulties local communities and response actors will face. The agricultural cycle has already been significantly disrupted, and this may result in longer-term food security issues.

I feel very upset, hopeless, and sad; we lost our education opportunities after the coup. The overall situation is troubling, and the military coup has worsened all aspects of health, education, and the social situation in our community. These conditions are the worst that I have ever faced in my life.[72]

While PDFs or other anti-coup armed groups have provided some services to date, they have limited time and resources to engage directly in emergency response activities. With PDF response capacity limited, there are critical gaps to be addressed by other actors in order to provide emergency support to vulnerable populations across the heartland.

There is a widespread sense that the resistance is on the right side of history, underpinning a large degree of solidarity and support for those suffering the impacts of armed violence. Displaced villagers fleeing to neighbouring villages find ready support. Infrastructure in the heartland is generally better than elsewhere in the country, and the lowland nature of the geography means that off-road routes are easily traversable—which is often not the case in the hilly and inaccessible border regions.[73] The strong levels of community support have precipitated brutal responses from the SAC, which seems to believe that to win control of the heartland they must destroy community resiliency.

Respondents said they prefer international response actors to engage with local actors—in particular, PAOs and PDFs—in the delivery of aid.[74] Indeed, according to many key informants interviewed for this research, these local actors are best positioned to understand the needs of conflict-affected communities and to reach them.

Local PDFs and PAOs are the best governance actors for international humanitarian organisations to engage with for the delivery of aid. They know the security situation, transportation routes, and the needs of the people the best. International humanitarian organisations can discuss with leaders how to deliver aid.[75]

A key challenge reported by response groups in the heartland is the difficulty of coordination with the plethora of armed actors on the ground. With multiple anti-coup armed entities active at the township level, sometimes in fraught relationship to one another, successfully coordinating and ensuring the safety of responders is challenging. The presence of Pyu Saw Htee or other pro-military armed actors is another threat, as these groups (and, likely, SAC leaders) suspect humanitarian assistance of being diverted to anti–coup armed entities.

More visible local response actors have been targeted by the SAC; this is especially true of local NGOs that were present in the region prior to the coup and then pivoted their programming to respond to the evolving context. Development/community organisations and other active community members banded together to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, organising locally, and linking up with national networks and supply chains to access healthcare and other support in order to offset health and economic impacts. In the aftermath of the coup, many of these groups shifted to support anti-coup resistance activities or conflict response, while others have been forced to disband in the face of SAC oppression.

Another important response mechanism in the heartland has come from religious institutions. Buddhist monks and other religious figures have not played massive roles in the resistance to the coup—a dynamic that is particularly clear when seen in contrast to the 2007 Saffron Revolution, which featured monk-led protests.[76] The less visible role of monks in the current resistance movement may be due to threats from the SAC; fears over the politicisation of religion; or the fact that COVID-19 prompted monks to move away from larger monasteries and back to their home villages, making organisation difficult. However, religious institutions have played a role in supporting communities affected by the conflict.

Buddhist institutions have supplemented the reduced role of local NGOs by raising funds and donating support to those in need. Key actors have included not only monks but also Gaw Ba Ka committees, which play a worldly role in monastic activities that monks are often removed from. Gaw Ba Ka committees take responsibility for finances at monasteries and pagodas, deciding how funds can best be used for the local community. As in conflict-affected areas elsewhere in Myanmar, monasteries have sheltered people fleeing conflict, while the host community provides food and other support. The SAC has tried to paint religious figures involved in this kind of assistance as ‘fake’ monks, in order to maintain its posture as the defender of Buddhism.

One respondent noted that religious institutions have played this crucial role for hundreds of years—supporting communities suffering the impacts of colonial wars between the Burmese empire and British; the WWII conflicts involving the Japanese; and the post-independence communist insurrection.[77] More than parahita actors,[78] these religious institutions are able to step up in times of crisis, drawing on hundreds of years of tradition. Indeed, Buddhist religious institutions and their surrounding communities live in a symbiotic relationship: the religious institutions rely on donations, alms, and patronage from the community, while the community relies on monasteries and their leadership for religious fulfilment, leadership, and guidance, as well as material support in times of need. Local religious leaders cannot drift far from community sentiment,[79] perhaps in contrast to some higher-level monks who rely on military patronage and have continued to align themselves with the military. Local monasteries are likely to remain reliable support systems for communities.

Looking forward, there is also some capacity to channel support from India through Chin State and into the heartland regions—albeit not without substantial delays and considerable risk due to the distance and conflict dangers separating these regions from the border with India’s Mizoram State. In terms of remote assistance delivery, financial contributions from abroad and within Myanmar are often directed to Mandalay, where they are used to purchase assistance materials that are delivered to vulnerable communities. Mandalay could be well positioned to serve—indeed, some reports suggest it is already serving—as a financial hub for incoming monetary donations from the diaspora and within Myanmar. Sources close to Mandalay-based activists indicate that the longtime financial hub is now functioning as a distribution centre from which underground networks are transporting emergency relief materials into the heartland to support communities in need.[80]

Additionally, Kachin response actors may be able to reach some parts of the heartland, particularly Sagaing Region. Although there is a robust network of Kachin civil society organisations, most Kachin response actors lack experience working in Sagaing, Magway, and Mandalay regions or working with ethnic Bamar communities, and thus do not have the requisite connections to launch activities in the heartland. Hurdles to a Kachin-led response in the heartland are further amplified by religious differences between Bamar and Kachin communities, which are particularly relevant given that the major Kachin civil society actors are heavily faith based (either Baptist or Catholic). That said, there are Christian and Kachin communities in parts of Sagaing Region, and Kachin civil society organisations could potentially serve as key intermediaries to leverage already established routes for the transport of essential supplies sourced from China through KIO/A territories and into the heartland. This approach could complement the ongoing response efforts of less-experienced actors who are carrying out emergency assistance efforts from Mandalay.

Response Implications

Intensifying medium-to-long-term armed conflict will continue to trigger serious, lasting impacts on communities throughout the heartland. With conflict expected to expand and escalate, innovative and flexible assistance-delivery modalities will be necessary to reach populations in need now and as armed violence intensifies. Assistance needs are urgent and substantial, and they will endure for the foreseeable future. Not only must the response immediately adjust to address the current needs of conflict-affected communities, but donors and aid agencies should prepare to provide ongoing support over time. Humanitarian response strategies for sustained intervention should be developed immediately to allow for urgent and continuous support to affected communities.

Increasingly important for any humanitarian access are armed anti-coup forces, PAOs, and other local actors affiliated with the NUG or broader anti-coup movement. With the collapse of the SAC’s governance in the heartland, these groups are developing mechanisms to support communities through provision of services such as administration, education, healthcare, and assistance for communities affected by conflict and crises. These actors, and the NUG itself, are now key stakeholders in the region and critical to the local response. Engagement with the NUG and local PAOs may provide critical insight into humanitarian needs on the ground and create opportunities to deliver assistance to people in need in hard-to-reach areas. Given there are already considerable structures in place for the delivery of humanitarian aid, it may be preferable for international agencies to support these structures, rather than developing their own.

It is also clear that the conflict landscape in the heartland is complex, with numerous armed and/or governance actors in each township, operating with varying levels of coordination and allegiance. Any conflict-sensitive humanitarian response to this crisis should involve an understanding of these dynamics, whether or not agencies are dealing with stakeholders to the conflict. This is also a matter of due diligence; agencies have a responsibility to understand the actors within the ecosystem in which they are seeking to intervene, to better define any risks associated with their activities.

A longstanding challenge for the international response in Myanmar has been navigating the complex ethnic and religious dynamics that characterise the country’s social fabric. This is just as relevant to the heartland crisis as it is to the borderland conflicts with which responders are more familiar. A conflict-sensitive response should be built on strong understandings of how minorities are relating to the crisis and its stakeholders; consultation with these communities regarding needs and priorities is thus essential. Muslims in the heartland, as in other parts of Myanmar, have long faced exclusion and discrimination, sometimes extending to violence. Many of the pro-SAC civilian militia groups were reportedly established by members of Buddhist nationalist networks, presenting serious concerns for Muslims in particular. There are non-Muslim minorities in the heartland as well, however, and further research is needed to better understand how diverse communities relate to the current crisis.

The humanitarian access challenges in the heartland can be at least partially overcome through remote programming modalities. Areas of emphasis should include resiliency support, emergency preparedness, and training on international humanitarian and human rights law, with a particular focus on the rights of those most vulnerable—including children, persons with disabilities, and women. Assistance through local responders and religious networks with better understanding of the local context, stronger relationships with stakeholders, and more accurate and up-to-date information with respect to security concerns in the heartland regions will support a more effective response.

Agencies seeking to provide effective humanitarian response in the heartland should also explore the opportunities to collaborate with actors and structures in adjacent areas. For instance, the KIO and civil society actors present in Kachin State have extensive experience and expertise in emergency response and protection activities, while civil society in the heartland has much more limited experience. Kachin-based actors may be able to assist in response activities to the Kachin-Sagaing borders, and perhaps deeper into the heartland in time. This presents a crucial opportunity to improve the delivery of life-saving assistance to conflict-affected communities in the heartland, and agencies with existing presence and networks in Kachin State will be best positioned to explore these opportunities for engagement.

Although civil society in Mandalay lacks the emergency-response experience of many borderland civil societies, the city is an established hub for financial networks and trade, and offers close proximity to the heartland crisis. Migration from across the heartland (and further afield) to Mandalay for work and education opportunities has also forged extensive networks between Mandalay and rural and semi-rural locations. These present opportunities for adaptation to the current crisis.

In the longer term, transitional justice and accountability mechanisms will be important for peace and governance efforts, and will rely on documentation of this phase of the crisis. Donors should ensure that civil society groups are well-equipped and trained to document atrocities, with the ultimate objective of holding perpetrators to account. The SAC’s crimes against civilians in the heartland replicate decades-long patterns of abuse in the ethnic borderlands, which the Myanmar military has inflicted with impunity; documentation capabilities in those border areas present opportunities for cross-learning and collaboration. Ongoing crimes should be closely tracked for human rights and atrocity documentation purposes, to facilitate accountability efforts.

Recommendations

- Design and deploy new, effective response strategies to address needs arising from intensifying armed violence. Conflict escalation over the medium to long term will continue to trigger serious, lasting impacts on communities throughout the heartland, and international responders should act now to devise and implement plans to channel assistance where it is needed and where it will be needed in future.

- Develop remote programming modalities through local responders and religious networks to provide crucial protection activities to vulnerable communities. Areas of emphasis should include resiliency support, emergency preparedness, and training on international humanitarian and human rights law, with a particular focus on the rights of those most vulnerable—including children, persons with disabilities, and women.

- Consider coordination with newly emerging local governance actors, such as PAOs. With the collapse of the SAC’s governance mechanisms, PAOs have taken on an important role in local responses and appear poised to grow in importance throughout the region. Open and frank dialogue with the NUG could help to identify potential avenues of collaboration with respect to assistance delivery throughout the heartland.

- Prioritise creative partnerships with existing local networks. There is a substantial, homegrown, and localised response network already in operation, consisting for the most part of informal groups and religious networks.

- Foreground contextual knowledge, underpinned by strong understandings of local dynamics and stakeholders, to strengthen the response. With multiple armed and governance actors present at the township level, due diligence, conflict sensitivity, and response effectiveness will rely on monitoring of the shifting context.

- Offer specific support for those most affected by the extreme violence ongoing across the heartland region, especially women. Women’s active participation in resistance, along with their general position of vulnerability and the impact of violence against women on the broader community, have likely driven an increased targeting of women. The violence and volatility of the current context have had an enormous impact on wellbeing, while psychosocial and mental health support remains extremely limited.

- Consult non-Bamar, non-Buddhist heartland minority communities on needs and response modalities. Many individuals comprising pro-SAC militia hail from Buddhist nationalist networks known for targeting Muslims and other minorities. A conflict-sensitive response and true protection for all communities can only be built on a thorough understanding of how minorities are relating to the current crisis.

- Explore opportunities for collaboration with actors in adjacent regions. In neighbouring Kachin State, civil society and governance actors have more experience in emergency response and are well-positioned, geographically, to reach heartland communities.

- Consider adapting networks and structures, including financial and civil society actors, in Mandalay to emergency response. Long a hub for trade and financial flows, Mandalay offers unique access points to rural and semi-rural communities now in crisis.

- Ensure that Myanmar civil society groups are resourced and trained to document atrocities for transitional justice and accountability mechanisms. There are opportunities to link networks in the heartland with human-rights and atrocity-documentation expertise in borderland communities, which have decades of experience documenting military abuses.

[1] The resistance looked to a long history of workers’ action. Strikes and boycotts characterised the pre-independence struggle against the British colonial state, a movement led by ethnic Bamar Buddhists, and more recent anti-military movements, such as the one that arose in 1988. Since the 2021 coup, government staff and administrators at all levels, from the village up, have resigned in the heartland. Young people planning resistance in central areas of Myanmar were also looking to the United League of Arakan/Arakan Army (ULA/AA) as a model. Indeed, the ULA/AA achieved significant success against the Myanmar military and Naypyidaw in a short period of time over 2018-2020, and resignations of government staff also formed part of its strategy, although to a lesser extent. Interviews carried out with community members in Monywa, Khin-U, Taze, and Kawlin Townships, Sagaing Region in March 2022 evidenced these dynamics. Confidential notes on file.

[2] Reha Kansara, “Defecting online: How Myanmar’s soldiers are deserting the army,” BBC News, 1 May 2022, https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-61243316.

[3] Interview with man, age unknown, Khin-U Township, Sagaing Region, March 2022. Confidential notes on file.

[4] Myanmar Emergency Update July 2022, UNHCR, 202, https://reporting.unhcr.org/document/2795.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Indeed, the heartland has not seen armed resistance to the Myanmar military or state since the communist insurrection, which declined dramatically from the 1960s.

[7] Although lying just south of the heartland, Naypyidaw Union Territory—which was partitioned from Mandalay Region when the new official capital city of Naypyidaw was established, in 2005—features a high concentration of Myanmar military forces and facilities, which formerly contributed to Mandalay’s long-standing, expansive military profile.

[8] Nationwide, the NLD won 258 out of 330 seats in the lower house, or Pyithu Hluttaw (People’s Parliament), and 138 of 168 seats in the upper house, or Amyothat Hluttaw (House of Nationalities).

[9] “Letpadaung mine protesters still denied justice,” Amnesty International, 27 November 2015, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2015/11/myanmar-letpadaung-mine-protesters-still-denied-justice/; Aung Zaw, “The Letpadaung Saga and the End of an Era,” Irrawaddy, 14 March 2013, https://www.irrawaddy.com/opinion/the-letpadaung-saga-and-the-end-of-an-era.html.

[10] CRPH Myanmar, “Declaration 13/2021 Informing the people of their Right to Self-defense…” Twitter, 15 March 2021, https://twitter.com/crphmyanmar/status/1371361961452085250?lang=en.

[11] Confidential interview notes on file.

[12] “Myanmar Villagers Take Up Homemade Weapons Against Regime’s Security Forces,” Irrawaddy, 2 April 2021, https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-villagers-take-homemade-weapons-regimes-security-forces.html.

[13] “The ‘Tumi Revolution’: Protesters fight back in Sagaing Region,” Frontier Myanmar, 13 April 2021, https://www.frontiermyanmar.net/en/the-tumi-revolution-protesters-fight-back-in-sagaing-region/.

[14] “Myanmar’s Shadow Government Forms People’s Defense Force,” Irrawaddy, 5 May 2021, https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmars-shadow-government-forms-peoples-defense-force.html.

[15] National Unity Government Myanmar, “Statement from the Ministry of Defence,” Twitter, 17 May 2021, https://twitter.com/nugmyanmar/status/1394308198941659138?lang=en; Interview on file.

[16] Helen Regan and Kocha Olarn, “Myanmar’s shadow government launches ‘people’s defensive war’ against the military junta,” CNN, 8 September 2021, https://edition.cnn.com/2021/09/07/asia/myanmar-nug-peoples-war-intl-hnk/index.html.

[17] Ministry of Defence homepage, National Unity Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, accessed on 25 January 2022, https://mod.nugmyanmar.org/en/. While the MOD’s website presents a straightforward structure of coordination and hierarchy, the reality is anything but.

[18] Namely: Defence Intelligence; Defence Policy and International Cooperation; Finance and Administration; Logistics and Materiel Acquisitions; Strategic Studies [note: not strategic command and control]; Recruitment and Manning; and Federal Military Affairs. Position titles are unofficial translations from Burmese. See: Ministry of Defense Organisational Structure, National Unity Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, accessed on 25 January 2022, https://mod.nugmyanmar.org/en/management-and-administration/.

[19] Confidential reports on file.

[20] The ULA/AA was launched in KIO/A territory with the active support of the KIO/A in 2009.

[21] “ကြားကာလ ဒေသန္တရအုပ်ချုပ်ရေး ဖော်ဆောင်ရာတွင် အခွန်ကောက်ခံခြင်းနှင့် မျှဝေသုံးစွဲခြင်းဆိုင်ရာ မူဝါဒ” [Taxation and sharing policy in developing interim local governance], National Unity Government Myanmar, 6 February 2022, .

[22] Interview with NUG official.

[23] Interviews on file.

[24] Interviews on file.

[25] “လူသတ်မှု ကျူးလွန်ခဲ့ဟု ယင်းမာပင် PDF ခေါင်းဆောင် ဗိုလ်သံမဏိ ဝန်ခံ” [PDF leader Captain Sammani admitted that he had committed murder], Irrawaddy Burma, 19 March 2022, https://burma.irrawaddy.com/news/2022/03/19/250706.html.

[26] “Local PDF leader confirms killing of 10 in Myanmar’s Sagaing region,” Radio Free Asia, 18 March 2022, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/killing-03182022212556.html.

[27] The group’s Myanmar name, နှလုံးလှလူမိုက်ကြီးများအဖွဲ့, is approximately translated as ‘gangsters with beautiful hearts’.

[28] “နှလုံးလှလူမိုက်ကြီးများအဖွဲ့မှ ၅ ဦးကို ဖမ်းဆီးမှု ညှိနှိုင်းဖြေရှင်းရန် NUG ညွှန်ကြား” [NUG directed to negotiate and resolve the arrest of 5 members of the ‘gangsters with beautiful hearts’ group], Myanmar Now, 26 May 2022, https://www.myanmar-now.org/mm/news/11456.

[29] The leader of the Yinmarbin PDF is Bo Than Mani, a former monk and a revolutionary veteran, having been involved in the 1988 uprising.

[30] Yangon Region had the third-highest number of cases.

[31] See for example: Final Report of the Independent International Fact-Finding Mission for Myanmar, United Nations Human Rights Council, 2018, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/MyanmarFFM/Pages/Index.aspx.

[32] “Myanmar Junta’s Worst Massacres of 2021,” Irrawaddy, 30 December 2021, https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-juntas-worst-massacres-of-2021.html.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Interview with woman, 19, Kawlin Township, Sagaing Region, March 2022.

[35] ပြည်သူ့အုပ်ချုပ်ရေးအဖွဲ့ or ပအဖ in Myanmar language, variously translated as ‘People’s Administration Organisation’, ‘People’s Administration Committee’, or ‘People’s Administration Team’. See, for example: Ministry of Home Affairs and Immigration – Myanmar, Facebook, 25 April 2022, https://www.facebook.com/mohaimyanmar/posts/307215721572329.

[36] Interview with man, 30, Monywa Township, Sagaing Region, March 2022.

[37] Interview with woman, unknown age, Sagaing Region, June 2022.

[38] Interview with woman, 19, Kawlin Township, Sagaing Region, March 2022.

[39] Interview with man, 40, Wetlet Township, Sagaing Region, March 2022.

[40] Interview with man, unknown age, Wetlet Township, Sagaing Region, June 2022.

[41] According to the independent organisation Data for Myanmar, the SAC has burnt down 18,886 houses across Myanmar since the coup, 13,840 of them in Sagaing Region and 3,055 of them in Magway Region. These figures include fires sparked by shelling and other attacks, as well as targeted arson. See: Data For Myanmar, Facebook post, 7 June 2022, https://www.facebook.com/data4myanmar/posts/1633821856986013.

[42] Ibid.

[43] “Military onslaught in eastern states amounts to collective punishment,” Amnesty International, 31 May 2022, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2022/05/myanmar-military-onslaught-in-eastern-states-amounts-to-collective-punishment/; Interviews on file.

[44] “Daily Briefing in Relation to the Military Coup,” Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, 27 July 2022, https://aappb.org/?p=22519.

[45] “Junta forces kill 20 civilians in one day in Myanmar’s Sagaing region,” Radio Free Asia, 5 May 2022, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/killings-05052022203642.html.

[46] “ပေါက်မြို့နယ် ကင်းမရွာမှာ မီးရှို့ခံရတဲ့အိမ် ၁၇၀ ကျော်ရှိလာ” [More than 170 houses were burned in Kinma village of Pao Township], Radio Free Asia, 18 April 2022, https://www.rfa.org/burmese/news/kinma-willage-fire-04182022084323.html.

[47] “Myanmar Junta Forces Rape and Kill Mother, Before Killing Her Two Daughters,” Irrawaddy, 9 March 2022, https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-junta-forces-rape-and-kill-mother-before-killing-her-two-daughters.html.

[48] Sebastian Strangio, “Myanmar Troops Massacre 11 Civilians in Sagaing: Reports,” The Diplomat, 10 December 2021, https://thediplomat.com/2021/12/myanmar-troops-massacre-11-civilians-in-sagaing-reports/; “Junta soldiers massacre and burn 11, including teenagers, during raid on village in Sagaing,” Myanmar Now, 7 December 2021, https://myanmar-now.org/en/news/junta-soldiers-massacre-and-burn-11-including-teenagers-during-raid-on-village-in-sagaing.

[49] Resisting the Resistance: Myanmar’s Pro-military Pyusawhti Militias, International Crisis Group, 2022, https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/myanmar/b171-resisting-resistance-myanmars-pro-military-pyusawhti-militias.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Interview with monk, 45, Taze Township, April 2022.

[52] Interview with male IDP camp volunteer, Chaung U Township, Sagaing Region, April 2022.

[53] Interview with female university student, Shwebo Township, Sagaing Region, April 2022.

[54] Sa Thant Zin, “Myanmar army to ‘accelerate’ operations in Sagaing with support of Pyu Saw Htee militias,” Myanmar Now, 27 March 2022, https://myanmar-now.org/en/news/myanmar-army-to-accelerate-operations-in-sagaing-with-support-of-pyu-saw-htee-militias.

[55] Perhaps the most famous incident occurred in Bangkok in 1941, when Myanmar independence hero Aung San and 25 of the ‘Thirty Comrades’ drew blood from their arms with syringes. The blood was poured into a silver bowl from which each of them drank, pledging their allegiance to the cause of independence. This group formed the basis of the Burmese Independence Army.

[56] “Pro-junta ‘Blood Comrades’ claim killings of 8 opposition members in Mandalay,” Radio Free Asia, 27 April 2022, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/militia-04272022203708.html.

[57] The most notorious example of this may be the Swan Arr Shin (‘Masters of Force’), a government-recruited civilian militia group active during the pre-2011 years of military rule. Thugs recruited by local offices of the Union Solidarity and Development Association (USDA)—the precursor to the military-linked Union Solidarity and Development Party—were also widely believed to have been involved in the 2003 Depayin (Tibayin) incident, when an NLD convoy carrying Aung San Suu Kyi was attacked. The government reported five deaths, while activists said that 70 had been killed. The military’s use of civilian-recruited thugs during the wave of anti-Muslim violence that overtook Myanmar in 2013–14 has also long been alleged. See: David I. Steinberg, Burma/Myanmar: What Everyone Needs to Know, Oxford University Press, 2010, p. 183; Zarni Mann, “A Decade Later, Victims Still Seeking Depayin Massacre Justice,” Irrawaddy, 31 May 2013, https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/a-decade-later-victims-still-seeking-depayin-massacre-justice.html;

“မႏၲေလး ေသြးေသာက္အဖြဲ႔ သူတို႔ဖြဲ႕စည္းတာမဟုတ္ စစ္ေကာင္စီျငင္းဆန္” [The Mandalay blood drinking group was not formed by the Military Council], Voice of America, 27 April 2022, ; “Pro-junta ‘Blood Comrades’ claim killings of 8 opposition members in Mandalay,” Radio Free Asia, 27 April 2022, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/militia-04272022203708.html.

[58] Interview on file.

[59] Resisting the Resistance: Myanmar’s Pro-military Pyusawhti Militias, International Crisis Group, 2022, https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/myanmar/b171-resisting-resistance-myanmars-pro-military-pyusawhti-militias.