Current Situation

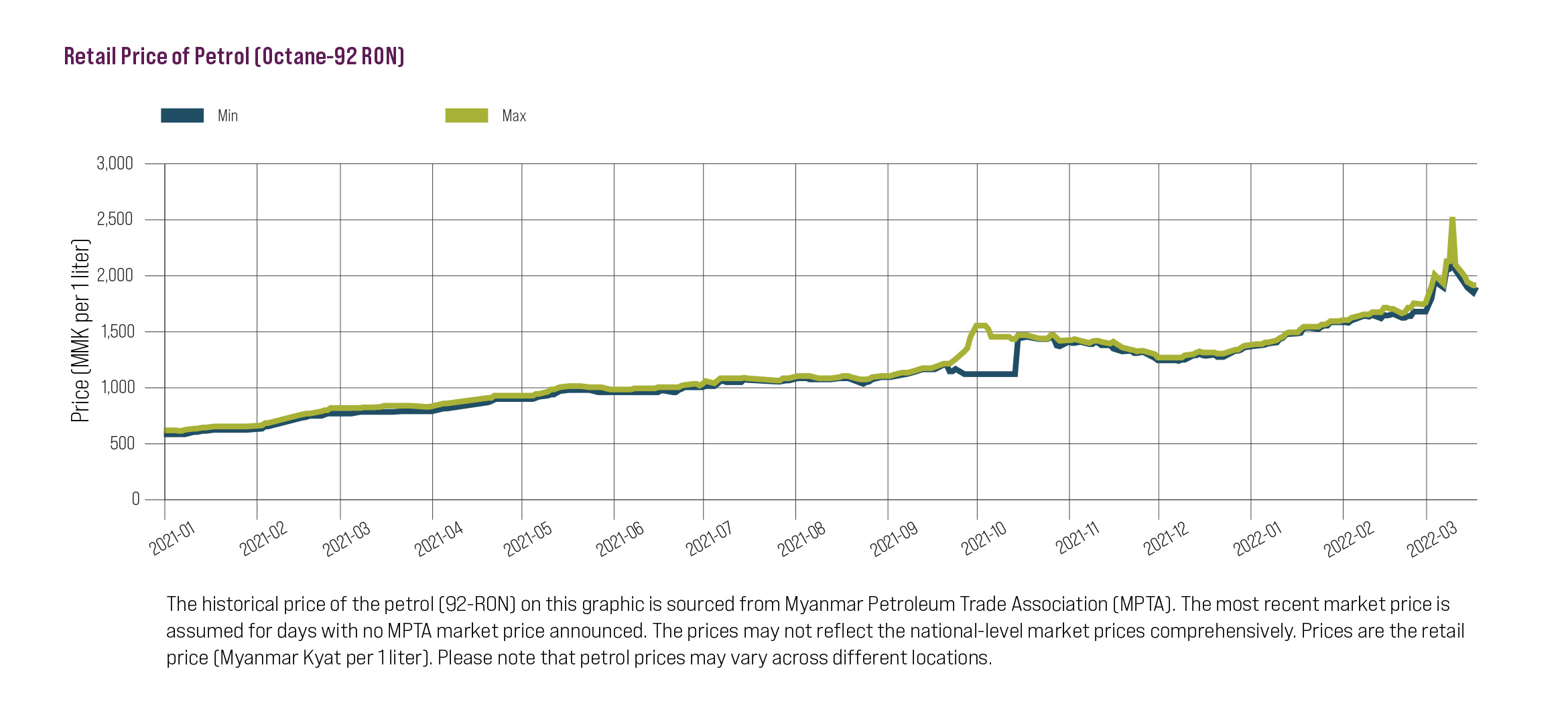

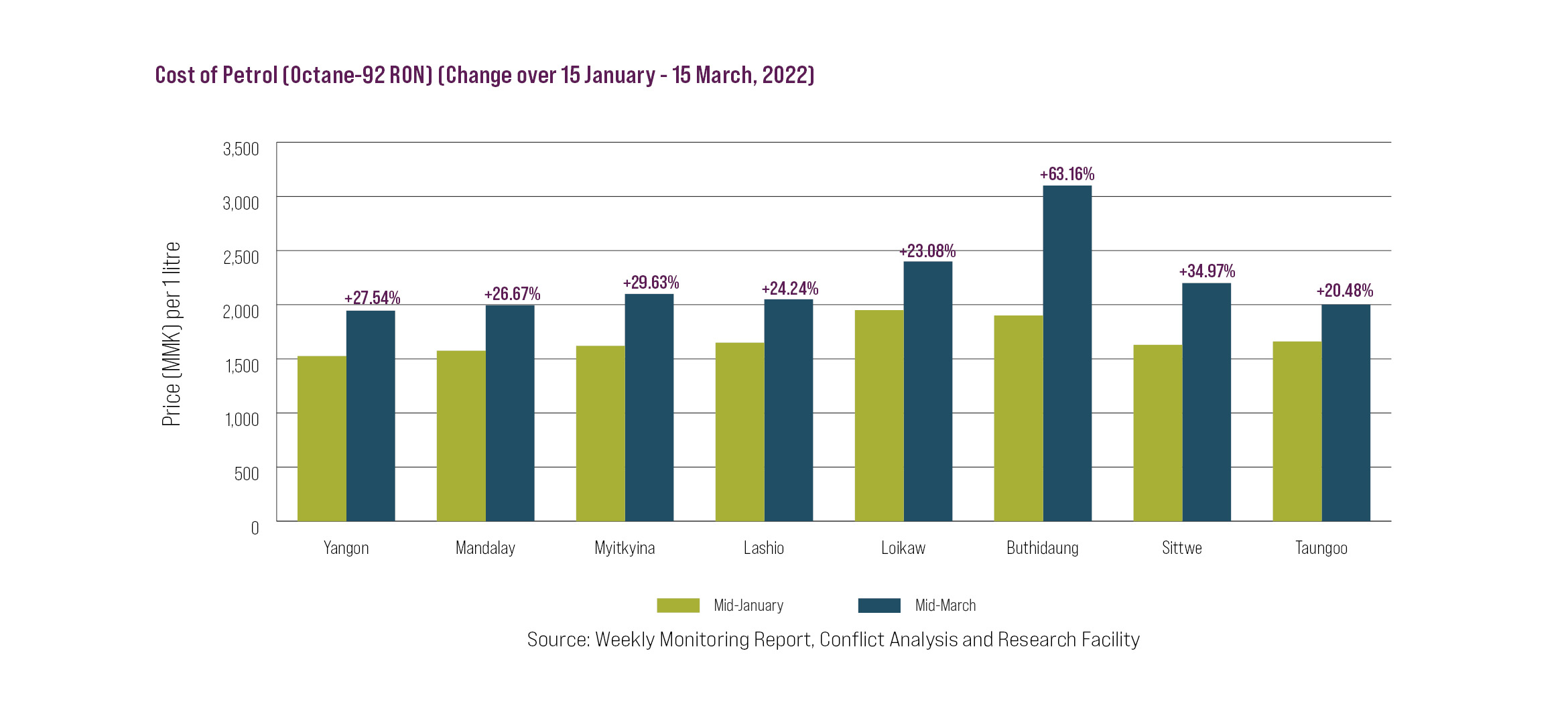

From September 2021 to March 2022, the average nationwide cost of fuel in Myanmar soared from around 1,500 to over 2,500 Myanmar Kyat (from 0.84 to 1.41 USD) per litre. In Kachin State, a Puta-O Town resident reported to this analytical unit that the price of fuel had climbed to more than 10,000 Myanmar Kyat (around 5.63 USD) per litre by 15 March 2022. The rising cost of fuel is placing additional strain on supply chains and markets. This trend has continued over recent weeks as prices have risen further, and has already raised the cost of transportation, production, and basic goods, which has led to the loss of small and medium enterprises and the livelihood opportunities they created. Higher fuel costs are having devastating impacts upon the growing number of vulnerable communities throughout Myanmar, where the COVID-19 pandemic and Min Aung Hlaing’s February 2021 military coup have crippled the national economy.

The collapse of Myanmar’s administrative and financial systems since February 2021 has rendered centralised mechanisms for market regulation, price control, and subsidy programs inoperable, leaving them unable to mitigate the impact of current fuel shortages on military elites and vulnerable communities alike. Fuel has become so precious that the State Administration Council (SAC) Ministry of Home Affairs requested a police escort for a convoy carrying fuel from Thailand,[1] and on 12 March, local media reported that Vice Senior General Soe Win told fellow State Administration Council cabinet members that their monthly fuel entitlements—previously up to 360 gallons for high level members—would be reduced from April.[2] In Rakhine State, high fuel prices this week forced many local fishing businesses to suspend operations, with sources warning local media that sustained price hikes could force businesses to close permanently.[3] Farmers who rely upon diesel to run agricultural machinery face growing difficulties in purchasing fuel to maintain their operations, causing many to consider reducing or suspending production.[4] Elsewhere, fighting has displaced farmers at key intervals of the agricultural cycle, which is expected to severely reduce yields and food availability in several regions, triggering greater dependence on food transported long distances at sharply rising cost.

Background

In Myanmar, oil more than doubled in cost—from an average of 700 Myanmar Kyat per litre before February 2021 to over 1,500 Myanmar Kyat per litre by September 2021—long before conflict in Ukraine drove fuel prices up globally in March 2022. The SAC’s inability to provide electricity has increased reliance on diesel powered generators for both domestic and industrial purposes, resulting in high consumption and demand for fuel. Falling foreign currency reserves have stifled diesel imports, which comprise approximately 98 per cent of Myanmar’s fuel consumption,[5] as have security concerns due to the ongoing political and economic upheaval, high shipping costs, and a sharp drop in the value of local currency. International enterprises may also be wary of potential sanctions, which have already targeted other lucrative extractive industries including gems and timber; human rights advocates have demanded sanctions on the sale of aviation fuel to the SAC in light of its continued attacks on civilians with airstrikes.[6]

Since February 2021, escalating armed conflicts across Myanmar interrupted supply chains throughout the nation, which had already been under strain due to the COVID-19 pandemic. SAC restrictions on transportation of goods to conflict areas and rising fuel costs made it difficult and expensive to access basic commodities; as prices increased, income levels plummeted. Even before the current fuel crisis exacerbated the myriad crises impacting vulnerable communities across Myanmar, UNDP predicted that nearly half of the population would be in poverty by early 2022,[7] and in January 2022 the World Bank estimated that Myanmar’s economy is up to 30% smaller than it was on track to become before the military seized power.[8] The collapse of the economy and devaluation of the Myanmar Kyat has had a substantial impact even on households where breadwinners remain employed, with 66 per cent reporting decreased income, leaving little ability to cope with the rising cost of basic commodities.[9] Fighting generated hundreds of thousands of IDPs who need urgent support, and has increased financial pressure on families who open their homes to displaced relatives and host communities that donate cash, food, and other supplies.

Impact

Rising fuel prices have led to higher costs for shipment of goods and public transportation, which have been defrayed to consumers who are struggling under the pressure of diminished livelihoods opportunities and the devaluation of the kyat. The climbing cost of gas is reflected across transportation services and has resulted in greater financial barriers to travel, which, in addition to restrictions on movement, limits communities’ access to livelihood opportunities, education, and healthcare—especially for those in rural areas. Communities that rely on distant urban clinics or hospitals in order to access healthcare now face substantial difficulty obtaining care, which undermines treatment. Given the growing transportation challenges, COVID-19 vaccines that rely on cold-chain supply routes are now even less likely to be distributed to rural villages.

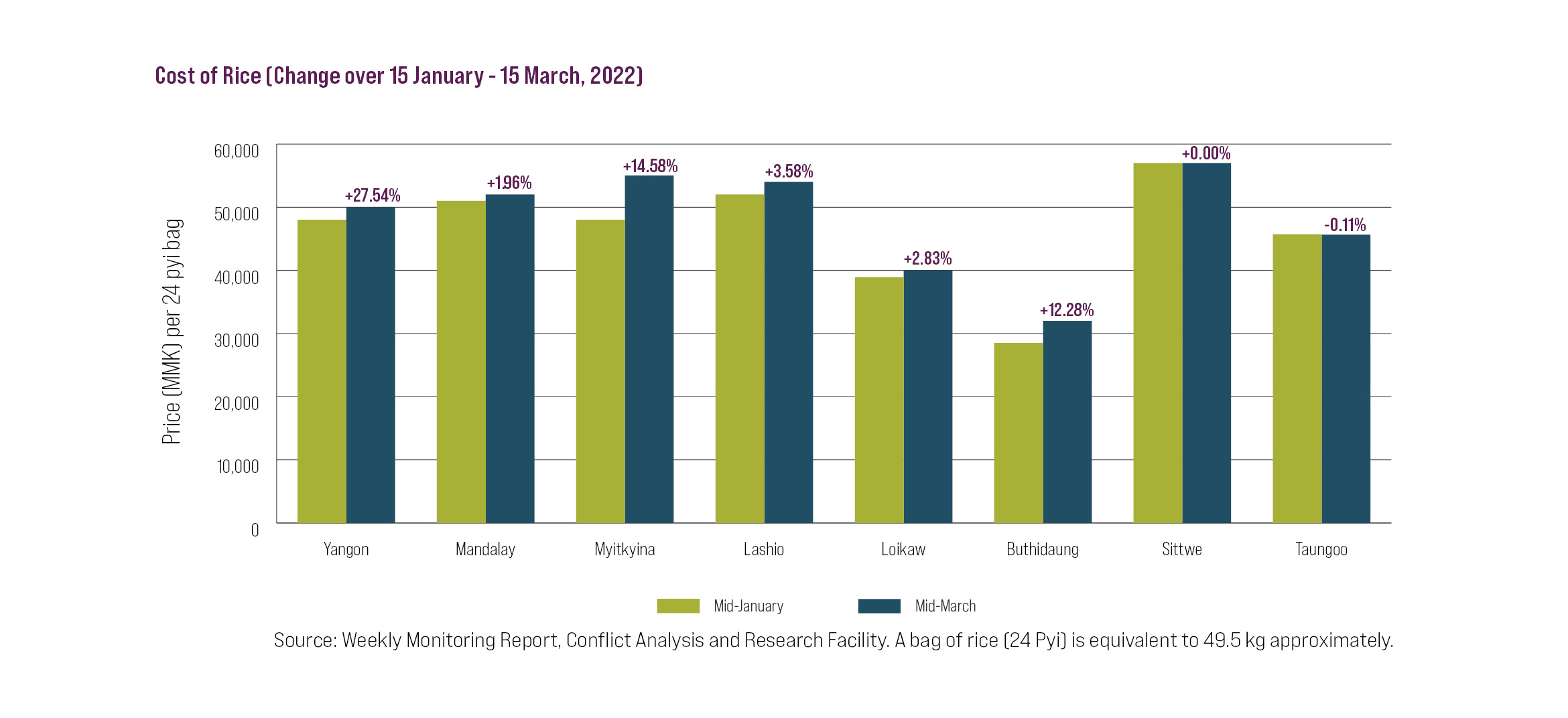

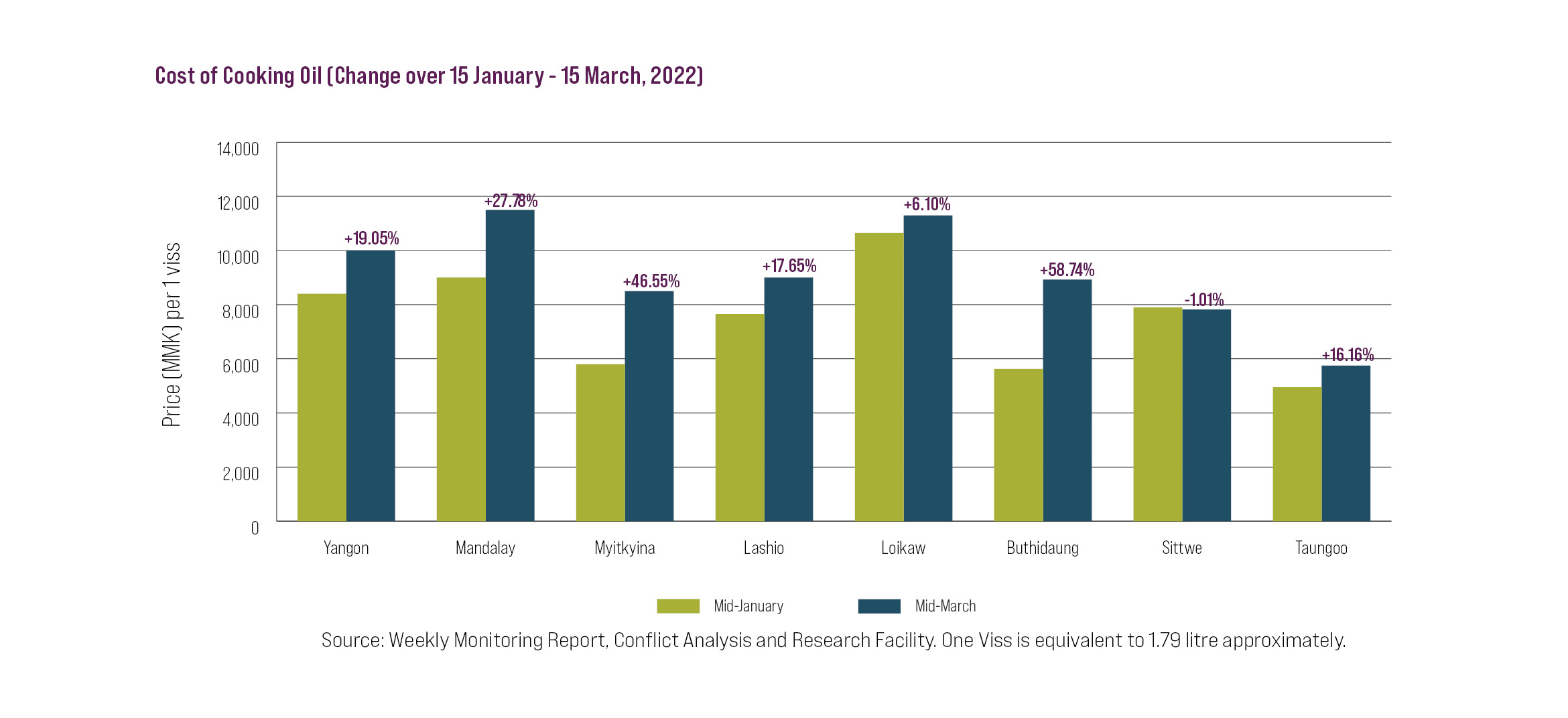

On 7 March 2022, the Ministry of Electricity announced that there would be temporary power outages between 12 and 18 March across the country, with all-day power cuts in some areas.[10] This has increased demand for alternative power sources like solar panels, driving up their cost. Electricity shortages have rendered water pumps inoperable for most of the day in cities like Yangon, as well as for farmers throughout Myanmar. Other agricultural inputs have also been limited, including the use of diesel-fueled equipment and inorganic fertilisers—another major Russian export—which can be expected to reduce crop yields, triggering greater dependence on food transported long distances at sharply rising cost. Daily staples, such as rice, have become significantly more expensive across many areas of Myanmar.

| Rice ( Per 24 Pyi bag – apprx 49.5 kg) | ||||||||

| Date/Localtion | Yangon | Mandalay | Myitkyina | Laisho | Loikaw | Buthitaung | Sittwe | Taungoo |

| Mid-Jan | 48000 | 51000 | 48000 | 52000 | 38900 | 28500 | 57000 | 45700 |

| Mid-March | 50000 | 52000 | 55000 | 54000 | 40000 | 32000 | 57000 | 45650 |

| Increased | 2000 | 1000 | 7000 | 2000 | 1100 | 3500 | 0 | -50 |

| Percent | 4.167% | 1.961% | 14.583% | 3.846% | 2.828% | 12.281% | 0% | -0.109% |

| Cooking Oil Per Viss ( apprx 1.79 L) | ||||||||

| Date/Localtion | Yangon | Mandalay | Myitkyina | Laisho | Loikaw | Buthitaung | Sittwe | Taungoo |

| Mid-Jan | 8400 | 9000 | 5800 | 7650 | 10650 | 5625 | 7900 | 4950 |

| Mid-March | 10000 | 11500 | 8500 | 9000 | 11300 | 8929 | 7820 | 5750 |

| Increased | 1600 | 2500 | 2700 | 1350 | 650 | 3304 | -80 | 800 |

| Percent | 19.05% | 27.78% | 46.55% | 17.65% | 6.10% | 58.74% | -1.01% | 16.16% |

| Petrol Per Litre | ||||||||

| Date/Localtion | Yangon | Mandalay | Myitkyina | Laisho | Loikaw | Buthitaung | Sittwe | Taungoo |

| Mid-January | 1525 | 1575 | 1620 | 1650 | 1950 | 1900 | 1630 | 1660 |

| Mid-March | 1945 | 1995 | 2100 | 2050 | 2400 | 3100 | 2200 | 2000 |

| Increased | 420 | 420 | 480 | 400 | 450 | 1200 | 570 | 340 |

| Percent | 27.54% | 26.67% | 29.63% | 24.24% | 23.08% | 63.16% | 34.97% | 20.48% |

Forecast

Impending food shortages, already considered likely, now may be worse and more difficult to mitigate. Conflicts have displaced farmers, disrupting subsistence and commercial agriculture operations; additionally, rising fuel costs are likely to continue to drive up costs of fertiliser,[11] farm equipment and its operation, and irrigation, compounding the problem and sparking nationwide food shortages over the coming year. Limitations on agricultural inputs will decrease yields, with the reduction in locally produced food driving an increased demand for imported food that will have to absorb the rising cost of transportation. These price hikes will have a wide impact on low-income families, especially on poor households for whom food is a higher share of expenses. Last year in Myanmar, 56 per cent of rural households’ total expenditures were on food, versus 43 per cent for urban households.[12] Rising oil prices are now triggering soaring production and living costs, which are in turn, forcing the closure of small and medium enterprises and eliminating jobs.

This will place additional pressure on all vulnerable communities affected by conflict and crises—not only IDPs. Families and community groups supporting IDPs in their homes or through individual donations will likely be less able to do so, local response mechanisms will likely weaken, and community resilience as a whole will likely suffer significantly. Furthermore, these informal support actors and host communities may find themselves struggling to meet their own needs amidst rising costs and disappearing supplies, leading them to also require assistance. The fallout from increased prices and decreased resources is likely to trigger greater reliance on negative coping mechanisms. For example, more people may take on illegal or dangerous work, such as human trafficking, drug production and trafficking, or participation in scams. Indeed, years of poverty and poor livelihood opportunities have contributed to the prevalence of a range of harmful and illicit practices in Northern Shan State, including scamming houses, human trafficking, risky migration, crime, debt, child labour, and child marriage. In hard to reach areas, these or similar impacts are likely to hit communities hardest—and these communities will likewise be the most out of reach of local and international responders.

Response Implications

With locally produced food less available after conflicts have interrupted agricultural cycles across Myanmar, more communities must rely on food imported from other regions or from abroad—which has increased in price to absorb the rising cost of transportation. Vulnerable communities enduring more restricted access to livelihoods, income, and cash thus face unprecedented challenges paying for food and essential goods. As the situation rapidly evolves and costs continue to rise, response activities will need to be designed and implemented quickly in order to ensure that at least immediate food assistance reaches vulnerable populations before procurement and delivery costs vastly exceed programme budgets. Access and delivery strategies for areas beyond the current geographic scope of the response should be devised in anticipation of looming nationwide food crises, to ensure unreached and underserved areas can receive rapid assistance. As direct access for international organisations remains almost entirely constrained in many areas of Myanmar, those relying on local implementing partners must increase their financial support of such actors to offset the burden of exponential price hikes across all activities. INGOs and donors should consult with local partners to ensure support is tailored to escalating operational costs and delivered through channels that minimise partners’ losses. In particular, exponential rises in travel costs mean that INGOs asking rural responders to travel great distances across unsafe areas in order to obtain programme funds from SAC banks are now presenting responders with a tremendous financial burden in addition to serious security risks. In view of this reality and the ongoing escalation of the economic crisis, inflexible funding mechanisms and traditional operating modalities are likely only to decrease in efficacy as means of support to Myanmar’s most vulnerable communities.

Food insecurity and high prices for basic commodities are expected to worsen due to the disruption of the previous harvest season by escalating conflicts, further contraction and obstruction of trade routes due to ongoing armed violence, and blocks imposed by SAC checkpoints on the provision of assistance. With no sign of conflict abating, displacement will continue to grow. Host communities that are continuing to support IDP populations with little assistance from response actors are expected to face growing difficulties themselves as their own access to cash and ability to purchase food and essentials diminishes sharply. In the coming months, vulnerable communities affected by conflict and crises are likely to be in urgent need of outside assistance as food stores and supplies run low, WASH facilities are overburdened, and shelter is insufficient for the coming monsoons. Avoidable health outcomes are likely to become more common among these and other underserved displaced communities due to reliance upon poor WASH facilities and prolonged exposure to wet conditions. Improved shelter, adequate WASH facilities, nutritious food assistance, and sufficient clothing are all in dire need, while procurement and delivery costs for each are climbing. Protection activities, medicine, and the provision of essential medical services are also needed to avert further avoidable negative impacts among affected communities, and budgets to provide these will likewise need to be increased to reflect rising prices.

Key Recommendations

- To cope with rising costs, response actors should urgently request additional funds to deliver planned support to vulnerable communities. As sharp increases in the cost of transportation and goods drive up program costs, budgets allocated based on prices before the fuel crisis will fall short of supporting planned activities. INGOs should critically reassess current work plans, realistically revise their projected delivery capacity, and draft amendments necessary to adjust ongoing projects. With assistance needs sharply rising across Myanmar, reductions in the scope and scale of response activities should be avoided in favour of budget amendments to reflect higher costs of transportation, goods, and services—with the understanding that costs will continue to rise.

- Donors should immediately release additional funds and allow for flexible amendments to existing programme plans. Rising electricity and transportation prices are driving up operational costs while programme inputs, particularly food baskets, are growing far more expensive. With both trends set to continue, implementing partners should be permitted to pull funds from other budget lines as an interim measure to meet the higher costs of delivering emergency assistance and avoid programme interruption. To ensure this practice does not later require other planned activities to be cut, donors should allocate and deliver additional funds to ensure partners are equipped with the financial resources to operate in a far more expensive environment.

- Response actors and donors should anticipate nationwide food shortages, and should prepare to deliver emergency food and cash assistance across all areas of Myanmar. Donors should allocate additional funds to enable a timely response to impending food shortages, which are likely to emerge at different times across different states and regions depending on local agricultural cycles and recent interruptions. Where safe and possible, response actors should preposition food stores, medical supplies and cash reserves, to facilitate rapid distributions to meet critical needs as they arise. In anticipation of the potential massive geographic scope of looming food insecurity, INGOs should devise access strategies, identify delivery mechanisms, and consider flexible and fast response modalities to reach all areas of Myanmar as and when needs become acute.

- International response actors should consider cost of living adjustments to ensure the wellbeing of Myanmar staff and local partners contending with exponential price increases. Salaries, benefits, and supplemental stipends should be examined in light of current and anticipated higher costs of goods and services to ensure staff and partners are able to provide for their families amidst escalating financial crises. International actors should avoid transferring the burden of the financial crisis onto staff and partners already navigating innumerable challenges to support response efforts at great personal risk.

- INGOs should expand programming—including through the immediate provision of higher amounts of cash and greater quantities of food assistance—to mitigate beneficiaries’ reliance on negative coping mechanisms and offset the impact of diminishing livelihood opportunities. The numbers of families without any source of income and individuals in need of urgent assistance are on track to continue to rise sharply; planned distributions should be scaled-up to reflect greater needs and higher costs, while additional and wider-reaching distributions should be scheduled to ensure expanding needs are met. Livelihood programmes should be adjusted to the current financial landscape and extended to wherever they are likely to deliver positive community impacts.

- INGOs should expand the scale and scope of assistance provided and integrate critical protection activities into each IDP site visit—including by supporting CSOs’ skill development across thematic areas and promoting collaboration among local responders with differing expertise in order to facilitate the provision of cross-cutting support during each visit to communities affected by conflict and crisis. By including multiple activities in each visit, responders will help ensure critical needs are met while improving efficiency, mitigating soaring transport and operational costs, and anticipating possible programming disruptions due to access restrictions or fuel and supply shortages. Delivery of explosive ordnance risk education (EORE), psychosocial support, and activities to prevent and address SGBV should be prioritised and integrated into planned aid distributions, while improvements to WASH and shelter facilities should likewise be undertaken to the extent possible during such visits.

[1] Khit Thit Media. “The military council ordered the police to provide road safety for a jet fuel tanker to pass through.” Facebook post. 10 Mar 2022. https://www.facebook.com/385165108587508/posts/1444784279292247/

[2] The irrawaddy. “Junta Watch: Ministers Told to Save Fuel, Coup Leader’s Mentor Makes Rare Appearance, and More.” Irrawaddy. 12 Mar 2022. https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/junta-watch-ministers-told-to-save-fuel-coup-leaders-mentor-makes-rare-appearance-and-more.html?fbclid=IwAR2cVUnBw069fPDbnLTNQ3Q5GP1aGBehKtoiKf7tTUtzAX9_o9ExL3x9ZKQ

[3] Development Media Group. “Some Arakan-based commercial fishing operations suspended due to rising fuel prices.” DMG. 11 Mar 2022. https://www.dmediag.com/news/4167-high-fuel-prices

[4] Interview on file

[5] Florence Tan. “Myanmar protests stall fuel imports, drive up costs.” Reuters. 19 Feb 2021. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-myanmar-oil-imports-idUSKBN2AJ0Z5

[6] Elaine Kurtenbach. “Rights advocates urge jet fuel sanctions against Myanmar.” Associated Press. 24 Feb 2022. https://apnews.com/article/business-myanmar-aung-san-suu-kyi-83079a61717f72b500cefc73cac1d35e

[7] UNDP. COVID-19, Coup d’Etat and Poverty: Compounding Negative Shocks and Their Impact on Human Development in Myanmar. (UNDP. 2021) https://www.asia-pacific.undp.org/content/rbap/en/home/library/democratic_governance/covid-19-coup-d-etat-and-poverty-impact-on-myanmar.html

[8] World Bank. “Economic Activity in Myanmar to Remain at Low Levels, with the Overall Outlook Bleak.” Press Release. 26 Jan 2022 https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/01/26/economic-activity-in-myanmar-to-remain-at-low-levels-with-the-overall-outlook-bleak

[9] OCHA. Myanmar Humanitarian Needs Overview 2022. (Relief Web. 2021) p15. https://reliefweb.int/report/myanmar/myanmar-humanitarian-needs-overview-2022-december-2021

[10] Eleven Media. “လျှပ်စစ်ဓာတ်အားထုတ်လုပ်မှု ၁၃၀၄ မဂ္ဂါဝပ်ခန့် လျော့နည်းမည်ဖြစ်သဖြင့် မတ် ၁၂ ရက်မှ ၁၈ ရက်အထိ အချို့နေရာများတွင် ၂၄ နာရီ ဝန်အားလျှော့ချခြင်း ဆောင်ရွက်မည်ဖြစ်ကြောင်း ထုတ်ပြန်” [The 24-hour load will be reduced from March 12 to 18 as some 1,304 megawatts of electricity will be reduced.] Eleven Media Group. 7 Mar 2021. https://news-eleven.com/article/226999

[11] International Food Policy Research Institute. The outlook for Myanmar’s inorganic fertilizer use and 2021 crop harvest. (IFPRI. 2021) https://www.ifpri.org/publication/outlook-myanmars-inorganic-fertilizer-use-and-2021-crop-harvest-ex-ante-assessment

[12] International Food Policy Research Institute. Myanmar’s poverty and food insecurity crisis. (IFPRI. 2021) https://www.ifpri.org/publication/myanmars-poverty-and-food-insecurity-crisis-support-agriculture-and-food-assistance